ABSTRACT

Background: The mental health impact of the COVID-19 crisis may differ from previously studied stressful events in terms of psychological reactions, specific risk factors, and symptom severity across geographic regions worldwide.Objective: To assess the impact of COVID-19 on a wide range of mental health symptoms, to identify relevant risk factors, to identify the effect of COVID-19 country impact on mental health, and to evaluate regional differences in psychological responses to COVID-19 compared to other stressful events.Method: 7034 respondents (74% female) participated in the worldwide Global Psychotrauma Screen – Cross-Cultural responses to COVID-19 study (GPS-CCC), reporting on mental health symptoms related to COVID-19 (n = 1838) or other stressful events (n = 5196) from April to November 2020.Results: Events related to COVID-19 were associated with more mental health symptoms compared to other stressful events, especially symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and dissociation. Lack of social support, psychiatric history, childhood trauma, additional stressful events in the past month, and low resilience predicted more mental health problems for COVID-19 and other stressful events. Higher COVID-19 country impact was associated with increased mental health impact of both COVID-19 and other stressful events. Analysis of differences across geographic regions revealed that in Latin America more mental health symptoms were reported for COVID-19 related events versus other stressful events, while the opposite pattern was seen in North America.Conclusions: The mental health impact of COVID-19-related stressors covers a wide range of symptoms and is more severe than that of other stressful events. This difference was especially apparent in Latin America. The findings underscore the need for global screening for a wide range of mental health problems as part of a public health approach, allowing for targeted prevention and intervention programs.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, global mental health, PTSD, anxiety, depression, insomnia, dissociation, risk factors, screening, public health

HIGHLIGHTS

In a large global sample, COVID-19 was associated with more severe mental health symptoms compared to other stressful or traumatic events.

The impact of COVID-19 on mental health differed around the world with an especially large impact in Latin America.

Video Abstract.

© 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

Short abstract

Antecedentes: El impacto de la crisis por la COVID-19 sobre la salud mental podría diferir de otros eventos estresantes estudiados con anterioridad en relación con reacciones psicológicas, factores de riesgo específicos y severidad de síntomas en diferentes regiones geográficas alrededor del mundo.

Objetivo: Evaluar el impacto de la COVID-19 sobre una amplia variedad de síntomas de salud mental, identificar los factores de riesgo relevantes, identificar el efecto que el impacto de la COVID-19 sobre un país ejerce, a su vez, sobre la salud mental, y evaluar las diferencias regionales en las respuestas psicológicas a la COVID-19 comparadas con otros eventos estresantes.

Método: 7034 encuestados (74 % mujeres) participaron en el Mapeo Global de Psicotrauma – Estudio de Respuestas Transculturales frente a la COVID-19(GPS–CCC, por sus siglas en ingles), reportando síntomas de salud mental relacionados a la COVID-19 (n = 1838) u otros eventos estresantes (n = 5196) de abril a noviembre del 2020.

Resultados: Los eventos relacionados a la COVID-19 se asociaron con un mayor número de síntomas de salud mental comparados con otros eventos estresantes, especialmente con síntomas del trastorno de estrés postraumático, ansiedad, depresión, insomnio, y disociación. La falta de apoyo social, los antecedentes psiquiátricos, el trauma infantil, los eventos estresantes adicionales ocurridos en el último mes y una baja resiliencia predijeron tener mayores problemas de salud mental por la COVID-19 y otros eventos estresantes. Un impacto más alto ejercido por la COVID-19 sobre un país se asoció, a su vez, con un mayor impacto sobre la salud mental, tanto por la COVID-19 como por otros eventos estresantes. Un análisis de las diferencias entre regiones geográficas reveló que en Latinoamérica se reportaron más síntomas de salud mental asociados a eventos relacionados con la COVID-19 en comparación con otros eventos estresantes, mientras que se observó un patrón opuesto en América del Norte.

Conclusiones: El impacto de los estresores asociados a la COVID-19 sobre la salud mental abarca un amplio rango de síntomas y es más severo que otros eventos estresantes. Esta diferencia fue especialmente evidente en Latinoamérica. Estos hallazgos enfatizan la necesidad de un tamizaje global para detectar una amplia gama de problemas de salud mental como parte de un enfoque de salud pública, permitiendo programas específicos de prevención e intervención.

PALABRAS CLAVE: COVID-19, salud mental global, trastorno de estrés postraumático, ansiedad, depresión, insomnio, disociación, factores de riesgo, tamizaje, salud pública

Short abstract

背景: 在世界各地, COVID-19危机对心理健康的影响可能与对先前研究的压力事件, 特定风险因素和症状严重程度的心理反应有所不同。

目的: 评估COVID-19对广泛心理健康症状的影响, 确定相关风险因素, 确定COVID-19国家对心理健康的影响, 并评估与其他压力事件相比对COVID-19的心理反应。

方法: 7034名受访者 (74%为女性) 在2020年4月至11月期间参加了世界范围的‘全球心理创伤筛查’—对COVID-19的跨文化反应研究 (GPS-CCC), 报告了COVID-19相关 (n = 1838) 或其他压力事件相关 (n = 5196) 的心理健康症状。

结果: 相较于其他压力事件, COVID-19相关事件与更多的心理健康症状相关, 尤其是PTSD, 焦虑, 抑郁, 失眠和解离症状。缺乏社会支持, 精神病史, 童年创伤, 在过去一个月中出现了更多的压力事件, 和低心理韧性, 预测了更多COVID-19和其他压力事件相关的心理健康问题。更高的 COVID-19国家影响与COVID-19和其他压力事件对心理健康的更大影响都相关。跨地区的差异分析表明, 在拉丁美洲报告了比其他压力事件更多的COVID-19相关事件的心理健康症状, 而在北美则相反。

结论: COVID-19相关压力源对心理健康的影响涵盖了一系列广泛症状, 并且比其他压力事件更为严重。这种差异在拉丁美洲尤为明显。结果强调了考虑到针对性预防和干预计划, 需要把对广泛心理健康问题进行全球筛查作为公共卫生方法一部分。

关键词: COVID-19, 全球心理健康, PTSD, 焦虑, 抑郁, 失眠, 解离, 风险因素, 筛查, 公共卫生

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has profoundly impacted all aspects of society, including mental health. The COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences may have hallmark characteristics of traumatic events, namely unpredictability, uncontrollability, and the threat of death or serious injury (Denckla, Gelaye, Orlinsky, & Koenen, 2020). However, the pandemic is distinct from typically reported traumatic events worldwide (Kessler et al., 2017) and does not represent an acute disaster or threat, rather a progressively emerging and potentially long-lasting life threat (Gersons, Smid, Smit, Kazlauskas, & McFarlane, 2020). COVID-19-related stressors may involve the disease itself (e.g. the physical-threat of contracting the disease, losing a loved one, the risk of infecting others, work-related stressors among, for instance, frontline workers), or may be due to the measures taken to limit transmission of the virus and their consequences (e.g. losing one’s home or job, social isolation, domestic violence, etc.). Together, these are likely to produce a sharp increase in a wide range of mental health problems, not limited to the most widely studied symptoms of anxiety and depression (e.g. Alexandra Maftei & Holman, 2021; Allan et al., 2020; Bareeqa et al., 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021; Cénat et al., 2021; de Pablo et al., 2020; Ertan, El-Hage, Thierree, Javelot, & Hingray, 2020; Greene et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2020; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020; Wu et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2020). Identifying the various mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic is a priority but still frequently neglected or minimized in national and international intervention plans (Brewin, DePierro, Pirard, Vazquez, & Williams, 2020). Reducing barriers to early screening for the variety of expressions of distress, especially in global populations, is essential to detect and prevent serious mental disorders (Michalopoulos et al., 2020).

Identifying specific risk factors that may moderate the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic can help inform prevention programs and psychosocial interventions (Duan & Zhu, 2020; Olff et al., 2019; Van Der Meer, Bakker, Van Zuiden, Lok, & Olff, 2020). Lack of social support is one of the most well-established risk factors for unfavourable outcomes after trauma (e.g. Olff, 2012); this may be particularly relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic, given lockdown and social distancing measures that make accessing in-person support more difficult (Qi et al., 2020). Other risk factors, such as experiencing additional stressors, having a psychiatric history, or having experienced childhood trauma, may also affect responses to COVID-19-related stressors (Kim, Nyengerai, & Mendenhall, 2020; Qi et al., 2020; Sherman, Williams, Amick, Hudson, & Messias, 2020; White & van der Boor, 2020; Xiong et al., 2020). Psychological resilience, on the other hand, may buffer stress responses (Denckla et al., 2020; van der Meer et al., 2018). Little is known about whether these established risk and protective factors for mental health problems following other traumatic events also influence COVID-19-related psychopathology, although there is some preliminary evidence showing that variables like being male, older, having no history of mental health difficulties, and higher levels of psychological well-being are predictors of resilience in the current pandemic (Valiente, Vazquez, Contreras, Peinado, & Trucharte, 2021).

Among the research priorities identified in response to the pandemic is ‘international collaboration and a global perspective’ (Holmes et al., 2020; McBride et al., 2020). Global collaboration will allow for accelerated research and innovative solutions (World Health Organization, 2020). Although many studies on the consequences of COVID-19 on mental health have been published, a recent meta-analysis was unable to compare the impact of specific regions due to a lack of global studies and overrepresentation of studies from China (Cénat et al., 2021). Globally, social and economic inequity may disproportionately affect certain geographic regions (Ahmed, Ahmed, Pissarides, & Stiglitz, 2020). If undetected, the observed mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in countries more severely affected or lacking essential healthcare and other resources, may become longer-term psychiatric disorders. Awareness of these problems and the differential vulnerability across countries is necessary to prevent an unprecedented public health impact worldwide. To contribute to this aim, we assessed stress responses to COVID-19-related stressors around the world.

The current study had four primary objectives. Firstly, we aimed to assess the impact of events related to COVID-19 on mental health symptoms and on specific symptom subdomains, compared to responses to other stressful events. Secondly, we aimed to assess the impact of specific risk factors on mental health problems related to COVID-19-related events versus other stressful events. Thirdly, we aimed to identify the effect of the COVID-19 country impact on mental health and to assess whether this impact differed for those reporting COVID-19-related events compared to other stressful events. Fourthly, we aimed to assess whether the impact of COVID-19-related events on mental health was different across United Nations (UN) regions compared to that of other stressful events.

1. Method

1.1. Participants and study procedure

As part of the Global Psychotrauma Screen – Cross-Cultural responses to COVID-19 study (GPS-CCC),www.global-psychotrauma.net/covid-19-projects 7048 participants were recruited around the globe from the 25th of April to the 30th of November in 2020 through the Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress website (Olff & Schnyder, 2021; Schnyder et al., 2017). The only inclusion criterion was lifetime exposure to a stressful event and the only exclusion criterion was being younger than 16 years old. In total, 14 participants were excluded based on their age, resulting in a final sample of 7034 participants. Participation was voluntary and no financial or material reward was offered. The Medical Ethical Review Committee of the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam exempted this study from formal review (W19_481 # 19.556). No identifying information was collected.

The link to the survey was posted on Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress (GC-TS) website endorsed by traumatic stress societies around the world. In addition, study ambassadors (61 in total) all over the world were asked to share the link to the survey as widely as possible, using social media and personal networks.

The online survey was offered in 21 languages. The survey automatically appeared in the language associated with the country of the IP address, but could be easily changed to another language if preferred. Consenting participants first completed several demographic questions and reported on the stressful event that currently affected them the most. Participants then completed the Global Psychotrauma Screen (GPS; https://gps.global-psychotrauma.net; Olff et al., 2020) and received immediate feedback on their scores.

1.2. Measures

1.2.1. Demographics

Demographic questions asked about the participant’s gender, age and country of residence. Survey completion time was also recorded. We also grouped countries in UN regions following the United Nations Statistics Division (https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49) with the exception combining ‘Northern Africa’ and ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’ because of the low numbers in Northern Africa.

1.2.2. Event characteristics

Information was collected about the stressful event identified by participants as the most impactful, including whether the event was related to COVID-19. Before starting the survey, participants were presented with information in line with the DSM-5 definition of a traumatic event:

Sometimes things happen to people that are unusually or especially frightening, horrible, or traumatic. This can be Corona virus (COVID-19) related events, or other events such as a serious accident or fire, physical or sexual assault or abuse, earthquake or flood, war, seeing someone be killed or seriously injured, or having a loved one die through homicide or suicide. […]

Also, the text entered in the open field was used where respondents were asked to enter what event or experience affected them most. In addition, participants were asked whether the event was work-related, about the time since the event took place, whether the event was a single or repeated/prolonged event, if the event involved physical violence, sexual violence, emotional abuse, serious injury, life-threatening situations, sudden death of a loved one, and/or the respondents causing harm to others. The latter were used to determine whether the event met the DSM-5 Stressor A criterion.

To determine whether the event was related to COVID respondents had to answer positive to the question:

‘Is your event Corona virus related?’ in the questions leading to the GPS and/or tick the box ‘Corona virus (COVID-19)’ in response to this question within the GPS: ‘Which of the below characterize the event (more answers possible)’.

1.2.3. Global Psychotrauma Screen (GPS)

The GPS includes 22 items assessing trauma-related symptomatology (17 items) and risk factors (5 items) in a dichotomous (yes/no) answer format (Frewen, McPhail, Schnyder, Oe, & Olff, 2021; Oe et al., 2020; Olff et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2021; Schnyder et al., 2017). All items are filled out considering the past month.

The total GPS symptom score is calculated by summing the 17 symptom items (range 0–17). GPS subdomain scores were calculated by averaging the item scores of a subdomain and range between zero and one. Subdomains include: posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 5 items), disturbances in self-organization (2 items), anxiety (2 items), depression (2 items), insomnia (1 item), self-harm (1 item), dissociation (2 items), substance abuse (1 item), and other stress-related problems (1 item). Higher total GPS symptom score and subdomain scores indicate higher symptom severity.

The 5 risk factors include: occurrence of other additional stressful events in the past month, lack of social support, childhood trauma, psychiatric history and lack of psychological resilience.

The GPS has been found valid and reliable in several studies (Frewen et al., 2021; Oe et al., 2020; Olff et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020, 2021). In the current study, the internal reliability of the total GPS symptom score was high (Cronbach’s α = .88) and comparable to other studies.

1.3. Statistical method

Most data were complete, except for information about respondent’s age (2% missing data), onset of the event (5.3% missing data), work-relatedness of the event (14.7% missing data), trauma frequency (18.2%) and respondent’s country of residence (2.6%). Missing data were imputed for all these variables except the respondent’s country with random forests using R package Missforest (normalized root mean squared error = .33 and proportion of falsely classified entries = .11; Stekhoven & Buhlmann, 2012).

Demographic information (age and gender) and information about the type of event (work-relatedness, trauma onset and trauma frequency) were added as covariates in all analyses. We did not correct for multiple comparisons, but only reported univariate results when the multivariate omnibus test was significant. The statistical assumptions of the analyses were met. Two-sided p-value <.05 was considered significant. Data were analysed using SPSS-26 and R version 3.6.1.

To extract information entered in the open text field where the respondent was asked to briefly describe the event or experience that currently affected them most, we implemented a topic model analysis using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model. All information from the open text field was first automatically translated into English via Google Translate and then checked and corrected if needed by authors with the original language as primary language. Before running the model, we converted all text to lowercase and removed English ‘stop words’ (i.e. very frequent words with low specificity), punctuation, and numbers. In order to identify the optimal number of topics, we trained a set of competing LDA models with the following k numbers of topics: 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30. Model training was performed on a random split including 90%, while 10% were used for model validation. The performance of the competing LDA models was compared by computing the perplexity statistic on the validation set (Wallach, Murray, Salakhutdinov, & Mimno, 2009); the optimal number of topics was selected using the heuristic approach proposed by Zhao et al. (2015), which is based on examination of the rate of perplexity change (RPC) across LDA models. The coherence of LDA-derived topic-words association was also examined visually using word clouds. Eventually, based on the RPC heuristic procedure and semantic coherence, we selected k = 30 as the final number of topics. As a last step, the selected model was applied on all available documents to generate the topic proportion scores. LDA analyses were performed using the Mallet software, version 2.08 (McCallum, 2002). Differences in topic proportions across groups were examined using t-test, and by computing Cohen’s d.

To address the first aim, comparing the impact of COVID-19 related events to other stressful events, we performed a linear regression analysis with GPS total score as dependent variable and type of event and covariates as independent variables to test whether COVID-19-related stressors were more strongly related to mental health compared to other stressful events. We also compared the impact of COVID-19-related stressors with other stressful events on the subdomains of the GPS with type of event and covariates as independent variables and with one-item subdomains as dependent variables in generalized linear models (family set to binomial) and with multiple item subdomains as dependent variables in a general linear model.

For the second aim, concerning the impact of the risk factors, two linear regression analyses were performed with GPS total score as dependent variable and with type of event, risk factors, the interaction effects between type of event and risk factors, and covariates as independent variables in the first model. The second model was similar to the first, but without non-significant interaction effects. In the case of significant interaction effects, probing of the interaction was used to determine the impact of risk factors for COVID-19-related and other stressful events separately.

Concerning the third aim, the COVID-19 country impact was calculated by taking the log of the total confirmed COVID-19 cases per million of inhabitants of the respondent’s country on the day the GPS was filled out. Two linear regression analyses were performed with GPS total score as the dependent variable and type of event, COVID-19 country impact, and covariates as independent variables in the first model; the event type*COVID-19 country impact interaction term was added in the second model.

Lastly, to compare the impact of COVID-19-related stressors across different regions in the world, two general linear models were performed with GPS total score as the dependent variable and type of event, United Nations (UN) region, and covariates as independent variables in the first model and the event type*UN region interaction term added in the second model.

2. Results

Surveys were completed by participants from 88 countries in 12 UN regions. Respondents had an average age of 38.46 years (SD = 14.36, range: 16–100) and were predominantly female (74%). Women (M = 7.88, SD = 4.59) reported higher total symptom scores than men (M = 6.06, SD = 4.71; t(7032) = 14.46, p < .001). Supplemental materials Table S1 displays GPS total and subdomain scores for men and women in several age groups.

2.1. COVID-19 versus other events

Approximately one-quarter (26.13%) of participants indicated that the event that affected them the most was related to COVID-19 (n = 1838), while the rest reported on another stressful event (n = 5196). Table 1 shows differences in demographics and trauma characteristics between participants reporting COVID-19-related versus other stressful events.

Table 1.

Differences in demographics and trauma characteristics between participants reporting a COVID-19-related versus other stressful events

| COVID-19(n = 1838) | Other(n = 5196) | t or χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39.65 (15.15) | 38.04 (14.05) | 4.12 | < .001 |

| Gender (female) | 1345 (73.2) | 3863 (74.3) | .96 | .33 |

| Trauma onset (longer than a year ago)1 | 366 (19.9) | 3377 (65.0) | 1108.22 | < .001 |

| Trauma frequency (single) | 1334 (72.6) | 3342 (64.3) | 41.57 | < .001 |

| Work-related event | 631 (34.3) | 1535 (29.5) | 14.61 | < .001 |

| Physical violence | 427 (23.7) | 1352 (27.4) | 9.58 | .002 |

| Sexual violence | 303 (16.8) | 920 (18.7) | 3.09 | .08 |

| Emotional abuse | 623 (34.5) | 2178 (44.2) | 50.56 | < .001 |

| Serious injury | 114 (6.3) | 527 (10.7) | 29.29 | < .001 |

| Life-threatening situations | 625 (34.6) | 1773 (36.0) | 1.00 | .32 |

| Sudden death of a loved one | 302 (16.5) | 1149 (22.9) | 32.91 | < .001 |

| Causing harm to others | 59 (3.2) | 154 (3.1) | .11 | .75 |

| Meeting DSM-5 criterion A | 982 (54.4) | 3654 (74.1) | 238.56 | < .001 |

Note: Age presented as M (SD) and t statistic; all other variables presented as n (%) and χ2 statistic. 1For some respondents, a COVID-19 event was related to another traumatic event that occurred longer than a year ago.

2.1.1. Events reported in text field

For participants who entered information in the text field, we compared topic proportions of participants reporting events related to COVID-19 (N = 1011) versus those reporting other events (N = 3201) using a series of t-tests. Out of 30 topics, 10 topics showed significant differences between the groups (Bonferroni corrected p < .05). Among participants reporting COVID-19-related events, we found increased proportions of topics about people dying of COVID-19 (top words: covid; hospital; died; sick; patient; doctor; positive; son; days; symptoms; tested; t = −7.52, df = 4210, p < .001), having to deal with negative consequences of the pandemic on jobs (top words: covid; work; job; corona; pandemic; virus; people; coronavirus; stress; time; t = −22.39, df = 4210, p < .001), COVID-19 affecting the health of family members (top words: family; covid; member; health; events; life; earlier; members; workplace; problems; t = −7.12, df = 4210, p < .001), and experiencing personal stress (top words: feel; person; people; anxious; sad; felt; feeling; relationship; afraid; remember; stressed; t = −3.58, df = 4210, p < .001).

In turn, participants reporting events not related to COVID-19 had a higher prevalence of topics about experiencing sexual abuse and assaults (top words: abuse; violence; assault; sexual; emotional; childhood; parents; physical; mother; relationship; t = 10.51, df = 4210, p < .001; top words: sexually; physically; husband; abused; assaulted; child; year; emotionally; closed; leave; knife; t = 3.94, df = 4210, p < .001; top words: man; street; night; house; long; hit; wanted; water; managed; broken; grabbed; walking; break; drunk; t = 3.68, df = 4210, p < .001), the suicide or illness of a spouse or relative (top words: mother; years; father; died; husband; life; time; relationship; child; daughter; months; disease; cancer; t = 5.97, df = 4210, p < .001; top words: death; loved; suicide; family; close; person; loss; illness; friend; father’s; father; relative; t = 7.05, df = 4210, p < .001), and car accidents and war (top words: accident; car; crash; war; injury; road; people; incident; killed; occurred; injured; injuries; t = 7.52, df = 4210, p < .001).

2.2. Responses to COVID-19 versus other events

When correcting for covariates (i.e. age, gender, event onset, event frequency, and work-relatedness), overall COVID-19-related stressors were related to higher GPS total symptom scores (M = 7.95) compared to other stressful events (M = 7.21; b = .75, t(7027) = 5.81, p < .001, η2 = .005). COVID-19-related stressors were also associated with higher subdomain scores of PTSD, disturbances in self-organization, anxiety, depression, dissociation, and other trauma-related mental health problems (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the models with GPS symptom subdomains predicted by type of event (COVID-19 versus other stressful events) controlling for covariates

| Subdomains | MCOVID-19 event | MOther event | B | Std error | t or Wald | p | Partial η2 or odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD | .51 | .46 | .05 | .01 | 5.02 | < .001 | .004 |

| DSO | .42 | .39 | .02 | .01 | 2.14 | .03 | .001 |

| Anxiety | .67 | .59 | .08 | .01 | 6.97 | < .001 | .007 |

| Depression | .62 | .55 | .07 | .01 | 5.72 | < .001 | .005 |

| Dissociation | .26 | .21 | .06 | .01 | 5.84 | < .001 | .005 |

| Insomnia | .56 | .54 | .09 | .06 | 1.97 | .16 | |

| Self-harm | .06 | .07 | −.05 | .11 | .22 | .64 | |

| Substance abuse | .27 | .28 | −.08 | .07 | 1.26 | .26 | |

| Other problems | .55 | .51 | .17 | .06 | 7.25 | .007 | 1.15 |

2.3. Risk and protective factors

All risk factors (additional stressful events, lack of social support, childhood trauma, psychiatric history, and lack of resiliency) predicted higher total GPS symptom scores for COVID-19 and other stressful events. However, significant interactions were found between event type and both experiencing additional stressful events (b = −.60, t(7020) = −2.90, p = .004, η2 = .001) and lack of social support (b = −.56, t(7020) = −2.74, p = .006, η2 = .001), suggesting that these risk factors had a more deleterious impact on stress responses for those reporting other stressful events. Details of the full model, including all main effects, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of linear model with GPS symptom score predicted by demographics, trauma characteristics and risk factors

| Variable | b | Std error | t | p | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 7.28 | .05 | 142.30 | < .001 | |

| Age | −.03 | .00 | −8.24 | < .001 | .01 |

| Gender (female) | .63 | .10 | 6.28 | < .001 | .006 |

| Trauma onset (longer than year ago) | −.51 | .10 | −5.26 | < .001 | .004 |

| Work-relatedness (yes) | −.07 | .09 | −.70 | .482 | .000 |

| Trauma frequency (single) | −1.95 | .10 | −20.23 | < .001 | .06 |

| Type of event (COVID-19) | .50 | .11 | 4.70 | < .001 | .003 |

| Stressful events in past month | 2.82 | .11 | 25.94 | < .001 | .09 |

| Lack of social support | 2.48 | .11 | 22.88 | < .001 | .07 |

| Childhood trauma | 1.08 | .09 | 11.80 | < .001 | .02 |

| Psychiatric history | 1.99 | .10 | 20.20 | < .001 | .06 |

| Resilience (lack of) | .65 | .11 | 6.11 | < .001 | .005 |

| Other events in past month * type of event | −.60 | .21 | −2.90 | .004 | .001 |

| Lack of social support * type of event | −.56 | .20 | −2.73 | .006 | .001 |

2.4. COVID-19 country impact and geographical differences

Correcting for covariates, higher COVID-19 country impact was related to higher GPS scores (b = .16, t(6835) = 4.87, p < .001, η2 = .003). This effect was not significantly different for COVID-19-related stressors compared to other stressful events (b = .05, t(6834) = .73, p = .47).

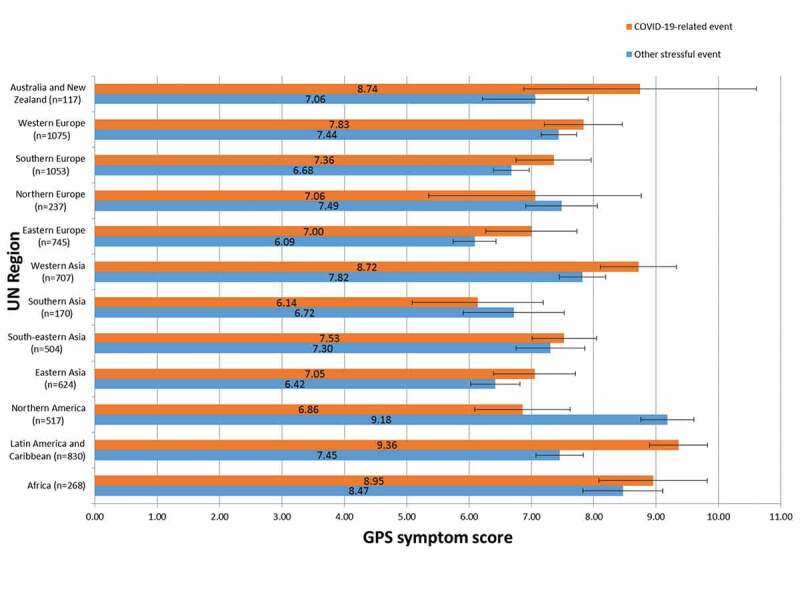

GPS scores differed between regions (F(11,6829) = 17.78, p < .001, η2 = .03) and this effect differed for COVID-19-related versus other stressful events (F(11,6818) = 6.33, p < .001, η2 = .01). Specifically, GPS scores in Latin America and the Caribbean were higher for COVID-19-related stressors, compared to other stressful events; conversely, in North America, GPS scores were higher for other stressful events, compared to COVID-19-related stressors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

GPS symptom score (mean and 95% confidence interval) as a function of UN region and type of event after controlling for covariates

3. Discussion

This study compared the impact of COVID-19-related stressors to other stressful events on a range of mental health symptoms in regions with varying degrees of COVID-19 burden worldwide. Reporting COVID-19-related events as the worst event, such as being infected oneself, assisting COVID-19 patients who were sick or dying, or having a family member being diagnosed with COVID-19, was associated with more mental health problems compared to non-pandemic-related events reported as the worst event. Specifically, more symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, disturbances in self-organization, and dissociation were reported. These findings add to previous studies showing elevated levels of anxiety (Bareeqa et al., 2020; Cénat et al., 2021; de Pablo et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2020), depression (Bareeqa et al., 2020; BinDhim et al., 2021; Cénat et al., 2021; de Pablo et al., 2020; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020; Wu et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2020), insomnia (Cénat et al., 2021; de Pablo et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021) and PTSD (Cénat et al., 2021; de Pablo et al., 2020; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020; Xiong et al., 2020) among the general population, health care workers and COVID-19 patients. The potential life threat posed by COVID-19 and the ongoing risk and uncertainty of when and how exposure and severe health consequences may occur represent peri-traumatic factors associated with psychopathology (Denckla et al., 2020). Given these factors, COVID-19-related events would indeed be expected to have a similar or even more severe impact on a wide range of mental health symptoms, compared to other stressful events.

Risk factors, including the occurrence of additional stressful events in the past month, lack of social support, childhood trauma, psychiatric history and low psychological resilience were associated with increased mental health problems, both in response to COVID-19-related and to other stressful events. This finding is in line with previous research (Kim et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2020; Sherman et al., 2020; White & van der Boor, 2020; Xiong et al., 2020) and suggests that COVID-19-related stressors, as with other stressful or traumatic events, disproportionately impact the mental health of those with more challenges and fewer resources. The need for prevention and intervention efforts directed specifically at those with these existing risk factors is, therefore, particularly high. Importantly, the negative mental health impact of additional stressful events in the past month and lack of social support was greater for those reporting a non-pandemic-related stressor. Potential reasons for this observed interaction remain speculative; however, decreased social contact caused by physical distancing measures may, for those experiencing COVID-19-related stress, represent a conscious behaviour that, in addition to a negative impact on mental health, also provides some sense of control. Or, from a positive psychology perspective, when facing uncertainty during a pandemic people may also develop positive coping, seek meaning, find ways to foster positive relationships, among other strategies (Valiente et al., 2021; Waters et al., 2021). Further research to identify individuals at risk for mental health problems related to COVID-19 is an immediate priority so resources can be directed towards those who need them most (Iob, Steptoe, & Fancourt, 2020).

Results of this study also provide information on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health across geographic regions. A higher COVID-19 impact in a country was related to more mental health symptoms. Interestingly, this effect was not different for responses to COVID-19-related stressors compared to other events. Possibly, stricter policies imposed by countries to contain the spread of the virus have equally affected those who reported COVID-19-related stressors and other events. Maekelae et al. (2020) found that dissatisfaction with governmental responses to the COVID-19 pandemic corresponded with increased distress levels, so it may also be the case that, for those in countries with lower COVID-19 impact, responses to traumatic events are less compounded by general distress.

The data from this global sample revealed differences across geographic regions in responses to COVID-19 versus other stressful events. Notably, in Latin America and the Caribbean, the level of mental health problems was high and especially so in response to COVID-19-related stressors. In North America, the opposite pattern was seen: symptoms were more often the consequence of stressors unrelated to COVID-19. The particularly high impact of COVID-19-related stressors on Latin America might be related to the low perceived efficacy of the government to stop the spread of COVID-19 (Benitez et al., 2020; Fetzer et al., 2020; Maekelae et al., 2020). Of note, these data were based on 8 months in the early phase of the pandemic (April-November 2020). Since then, the situation has become even worse in Brazil (Castro et al., 2021). The high symptom profiles in response to other stressors in Northern America may be, in part, explained by the time of data collection, which coincided with nation-wide racial conflicts and civil unrest related to the presidential elections in the USA. Previous elections have been associated with clinically significant symptoms of distress in a quarter of the respondents (e.g. Hagan, Sladek, Luecken, & Doane, 2020).

Disaster research from around the world suggests that large-scale crises, such as a global pandemic, may be followed by a ‘second disaster’, especially when the first crisis is associated with psychosocial disruptions, practical and financial problems, and complex community and political issues (Gersons et al., 2020). The mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic may also add to the increasing worldwide psychosocial burden related to social inequality, the consequences of climate change, migration, extremism, and polarization of societies (Kessler et al., 2011; Webb Hooper, Napoles, & Perez-Stable, 2020). Inequitable responses to the pandemic are likely to occur, and, in fact, are already emerging (e.g. vaccination programs are less available to low-income countries).

Cross-cultural differences in response to various types of traumatic experiences may exist. In some societies, individuals may be less likely to respond to items on alcohol or drug use and stigma may exist in reporting on COVID-19 or other events associated with sexual violence or abuse (Oe et al., 2020). Although within-region comparisons demonstrate differential responses to COVID-19 versus other events, further research is needed into the societal and cultural aspects behind these different regional profiles.

Some low-income countries, especially African countries, were underrepresented in the current study. It is unclear why there was less uptake in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to, for instance, South America. We had a similar number of ambassadors and society representatives in both continents. This may, in part, relate to the online data collection, thus requiring access to the internet and a computer or other smart device. On the other hand, mobile phones are widely available even in Africa (Olff, 2015). Given that poorer populations already lack access to health services under ordinary circumstances, they will be left most vulnerable during times of crisis. Future research is needed in these areas, including conflict zones, and refugee populations (Ahmed et al., 2020).

Additional limitations of the present study include the non-probability sample, which was predominantly female (74%). However, one might argue that this is consistent with representative samples of traumatized adults where women have a two to three times higher risk of posttraumatic stress reactions such as PTSD (Olff, 2017; Olff, Langeland, Draijer, & Gersons, 2007). The study would benefit from a replication in a representative worldwide sample. Dividing participants by those reporting COVID-19 versus Other events as the worst event is a simplification of real life, as participants may experience both types of events. In spite of this limitation, we found significant differences between the two groups. Furthermore, data were collected cross-sectionally over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic not allowing for longitudinal analyses of mental health problems within-persons. Data were collected before mutations were detected in the UK, South-Africa or Brazil, and before vaccination programs started. Previous studies indicated that mental health problems due to COVID-19 might be the most severe at the start of the pandemic (e.g. Daly, Sutin, & Robinson, 2020). Future studies might evaluate the mental health impact of COVID-19 over time and compare stress responses between different ‘waves’ of infections, as well as before and after the implementation of vaccination programs. Furthermore, similar to other trauma-related questionnaires like the PC-PTSD-5 or PCL-5, these are only filled out when the respondent has experienced a stressful event that is likely to meet the A criterion. Finally, symptoms in this study have been assessed with a brief screening tool and would require follow-up with clinician-administered instruments to provide more accurate assessments of mental health symptoms and disorders (Ransing et al., 2020).

This study provides insight into the mental health impact of the COVID-19 crisis. Specifically, results of this study suggest that, globally, the COVID-19 pandemic leads to a wide range of mental health symptoms and that countries with higher rates of infections are more vulnerable. The findings also imply that COVID-19, like other traumatic stressors, disproportionately impacts the mental health of those with pre-existing risk factors such as previous developmental trauma, mental health problems and low social support. Furthermore, region-specific differences in response to the pandemic were shown. In addition, the GPS represents a free of charge and easy-to-use (e.g. online) multilingual screening instrument that may help detect mental health problems and allow for mitigation of the mental health consequences that will spread long after the pandemic is resolved and may affect a large proportion of the global population.

Stress in the face of a life-threatening pandemic may be a normal reaction to an abnormal situation and should not be automatically pathologized. However, the current findings confirm that the ongoing and global nature of the pandemic is a major public mental health concern (Denckla et al., 2020). Although some intervention efforts exist (e.g. REACH for Mental Health; https://www.global-psychotrauma.net/COVID-19-projects; Denckla et al., 2020), it is imperative that we monitor the evolution of mental health symptoms in the context of the COVID-19 and continue to develop globally accessible and effective interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all ambassadors of the Global Psychotrauma Screen – Cross-Cultural responses to COVID-19 versus other traumatic events (GPS-CCC) study who helped include participants around the world, in particular:

Sara Belquaid, Jonathon Bisson, Aida Dias, Maryke Hewett, Yoshiharu Kim, Juliana Lanza, Weili Lu, Patrick Lorenz, Marcelo Mello, Gladys Mwiti, Zhonglin Tan, Anne Wagner.

Funding Statement

This study was supported in part by the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (Lembaga Pengelola Dana Pendidikan/LPDP) Ref: S-395/LPDP.3/2019; the Chinese Scholarship Council (NO. 201504910771); the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001; the CARIPARO (Cassa di Risparmio di Padova e Rovigo) Foundation research fellowship; and the Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress. Funding to build the Global Psychotrauma Screen application was provided by R. Morgado, Synappses social enterprise.

Disclosure statement

Wissam El-Hage received personal fees from Air Liquide, EISAI, Janssen, Lundbeck, Nordic Pharma, Otsuka, UCB, Roche and Chugai. No potential competing interest was reported by the other authors.

Data availability statement

Raw data were generated through the Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress (GC-TS). Derived data of this study are available on the GC-TS website: www.global-psychotrauma.net.

The data described in this article are also openly available in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/untsy/.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Open Data. The data are openly accessible at https://osf.io/untsy/.

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Open Data. The data are openly accessible at https://osf.io/untsy/.

Author contribution

MO was responsible for the conception and design, CH analysed the data, all (group) authors contributed to the writing and approved the final version of the article.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Consortium

Helene F. Aakvaag, Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies, Oslo, Norway.

Dean Ajdukovic, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia.

Anne Bakker, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Department of Psychiatry, Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Erine E. Bröcker, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa.

Lucia Cantoni, University of Padua, Department of Phylosophy, Sociology, Pedagogy and Applied Psychology (FISPPA), Padua, Italy.

Marylene Cloitre, National Center for PTSD Dissemination and Training Division, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Stanford University, Menlo Park, CA, USA.

Erik LJL de Soir, Department of Scientific and Technological Research, Royal Higher Institute of Defence, Belgium.

Małgorzata Dragan, Facultry of Psychology, University of Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland.

Atle Dyregrov, Center for crisis psychology, University of Bergen, Norway.

Wissam El-Hage, UMR 1253, iBrain, Université de Tours, CHRU de Tours, Inserm, Tours, France.

Julian D Ford, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Dept Psychiatry, Farmignton CT, USA.

Juanita A Haagsma, Department of Public Health, Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Jana D Javakhishvili, ILia State University, School of Arts and Science, Tbilisi, Georgia.

Nancy Kassam-Adams, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Center for Injury Research & Prevention, Philadelphia, USA.

Christian H Kristensen, School of Health and Life Sciences, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Rachel Langevin, McGill University, Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology, Montréal, Canada.

Juliana A Lanza, Traumatic Stress Unit, Alvear Hospital - Human Factors SAME, Buenos Aires City, Argentina.

Brigitte Lueger-Schuster, University of Vienna, Faculty of Psychology, Unit of Psychotraumatology, Vienna, Austria.

Leister SS Manickam, Centre for Applied Psychological Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, India.

Davide Marengo, Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Italy.

Marcelo, F, Mello, Department of Psyhchiatry, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, Brazil.

Angela Nickerson, School of Psychology, UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW Australia.

Misari Oe, Department of Psychiatry, Kurume University School of Medicine.

Mihriban Heval Ozgen, LUMC, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Daniela Rabellino, Department of Psychiatry, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada.

Luisa Sales, Centro De Trauma, CES, University of Coimbra, and Hospital Militar de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal.

Carolina Salgado, Universidad Catolica del Maule, Department of Psychiatry, Talca, Chile.

Julia Schellong, Medical Faculty, Clinic of Psychotherapy and Psychosomatic, Technical University Dresden.

Ulrich Schnyder, University of Zurich, Switzerland.

Soraya Seedat, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa.

Nadezhda B Semenova, Scientific Research Institute of Medical Problems of the North, Krasnoyarsk, Russian Federation.

Andrew J Smith, University of Utah School of Medicine, Dept of Psychiatry, Huntsman Mental Health Institute, Salt Lake City, UT, USA.

Sjacko Sobczak, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience (MHeNS), Department of Psychiatry and Neuropsychology, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Jackie June ter Heide, ARQ National Psychotrauma Centrum, Diemen, The Netherlands.

Carmelo Vazquez, Faculty of Psychology, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain.

Janaina Videira Pinto, The University of Sydney, Faculty of Medicine and Health, Sydney, Australia.

Anne C Wagner, Remedy, Canada.

Li Wang, Laboratory for Traumatic Stress Studies, CAS Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China.

Irina Zrnic, University of Vienna, Faculty of Psychology, Unit of Psychotraumatology, Vienna, Austria.

References

- Ahmed, F., Ahmed, N., Pissarides, C., & Stiglitz, J. (2020). Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Health, 5(5), E240–12. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30085-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandra Maftei, A., & Holman, A. C. (2021). The prevalence of exposure to potentially morally injurious events among physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1). doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1898791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan, S. M., Bealey, R., Birch, J., Cushing, T., Parke, S., Sergi, G., … Meiser-Stedman, R. (2020). The prevalence of common and stress-related mental health disorders in healthcare workers based in pandemic-affected hospitals: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1810903. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1810903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bareeqa, S. B., Ahmed, S. I., Samar, S. S., Yasin, W., Zehra, S., Monese, G. M., & Gouthro, R. V. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in China during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 009121742097800. doi: 10.1177/0091217420978005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez, M. A., Velasco, C., Sequeira, A. R., Henriquez, J., Menezes, F. M., & Paolucci, F. (2020). Responses to COVID-19 in five Latin American countries. Health Policy and Technology, 9(4), 525–559. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BinDhim, N. F., Althumiri, N. A., Basyouni, M. H., Alageel, A. A., Alghnam, S., Al-Qunaibet, A. M., … Ad-Dab’bagh, Y. (2021). Saudi Arabia Mental Health Surveillance System (MHSS): Mental health trends amid COVID-19 and comparison with pre-COVID-19 trends. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1875642. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1875642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin, C. R., DePierro, J., Pirard, P., Vazquez, C., & Williams, R. (2020). Why we need to integrate mental health into pandemic planning. Perspectives in Public Health, 140(6), 309–310. doi: 10.1177/1757913920957365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M. C., Kim, S., Barberia, L., Ribeiro, A. F., Gurzenda, S., Ribeiro, K. B., … Singer, B. H. (2021). Spatiotemporal pattern of COVID-19 spread in Brazil. Science, eabh1558. doi: 10.1126/science.abh1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat, J. M., Blais-Rochette, C., Kokou-Kpolou, C. K., Noorishad, P.-G., Mukunzi, J. N., McIntee, S.-E., … Labelle, R. P. (2021). Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 295, 113599. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly, M., Sutin, A. R., & Robinson, E. (2020). Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Psychological Medicine, 1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720004432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pablo, G. S., Vaquerizo-Serrano, J., Catalan, A., Arango, C., Moreno, C., Ferre, F., … Fusar-Poli, P. (2020). Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denckla, C. A., Cicchetti, D., Kubzansky, L. D., Seedat, S., Teicher, M. H., Williams, D. R., & Koenen, K. C. (2020). Psychological resilience: An update on definitions, a critical appraisal, and research recommendations. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1822064. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1822064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denckla, C. A., Gelaye, B., Orlinsky, L., & Koenen, K. C. (2020). REACH for mental health in the COVID19 pandemic: An urgent call for public health action. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1762995. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1762995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan, L., & Zhu, G. (2020). Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), 300–302. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertan, D., El-Hage, W., Thierree, S., Javelot, H., & Hingray, C. (2020). COVID-19: Urgency for distancing from domestic violence. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1800245. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1800245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer, T., Witte, M., Hensel, L., Jachimowicz, J., Haushofer, J., Ivchenko, A., … Yoeli, E. (2020). Global behaviors and perceptions in the COVID-19 pandemic. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from www.nber.org/papers/w27082. [Google Scholar]

- Frewen, P., McPhail, I., Schnyder, U., Oe, M., & Olff, M. (2021, in press). Global Psychotrauma Screen (GPS): psychometric properties in two internet-based studies. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1). doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1881725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersons, B. P. R., Smid, G. E., Smit, A. S., Kazlauskas, E., & McFarlane, A. (2020). Can a ‘second disaster’ during and after the COVID-19 pandemic be mitigated? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1815283. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1815283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, T., Harju-Seppänen, J., Adeniji, M., Steel, C., Grey, N., Brewin, C. R., … Billings, J. (2021). Predictors and rates of PTSD, depression and anxiety in UK frontline health and social care workers during COVID-19. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1882781. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1882781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, M. J., Sladek, M. R., Luecken, L. J., & Doane, L. D. (2020). Event-related clinical distress in college students: Responses to the 2016 U.S. Presidential election. Journal of American College Health, 68(1), 21–25. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1515763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, E. A., O’Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., … Bullmore, E. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iob, E., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(4), 543–546. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., … Survey, W. W. M. H. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), 1353383. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C., Green, J. G., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Bromet, E., Cuitan, M., … Zaslavsky, A. M. (2011). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative (vol 19, pg 4, 2010). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 20(1), 62. doi: 10.1002/mpr.333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A. W., Nyengerai, T., & Mendenhall, E. (2020). Evaluating the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: Perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and childhood trauma predict adult depressive symptoms in urban South Africa. Psychological Medicine, 1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720003414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekelae, M. J., Reggev, N., Dutra, N., Tamayo, R. M., Silva-Sobrinho, R. A., Klevjer, K., & Pfuhl, G. (2020). Perceived efficacy of COVID-19 restrictions, reactions and their impact on mental health during the early phase of the outbreak in six countries. Royal Society Open Science, 7(8), 200644. doi: 10.1098/rsos.200644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride, O., Murphy, J., Shevlin, M., Gibson-Miller, J., Hartman, T. K., Hyland, P., … Bentall, R. P. (2020). Monitoring the psychological, social, and economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the population: Context, design and conduct of the longitudinal COVID-19 psychological research consortium (C19PRC) study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 30(1). doi: 10.1002/mpr.1861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, A. K. (2002). A machine learning for language. Retrieved from http://mallet.cs.umass.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Michalopoulos, L. M., Meinhart, M., Yung, J., Barton, S. M., Wang, X. Y., Chakrabarti, U., … Bolton, P. (2020). Global posttrauma symptoms: A systematic review of qualitative literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 21(2), 406–420. doi: 10.1177/1524838018772293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oe, M., Kobayashi, Y., Ishida, T., Chiba, H., Matsuoka, M., Kakuma, T., … Olff, M. (2020). Screening for psychotrauma related symptoms: Japanese translation and pilot testing of the Global Psychotrauma Screen. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1810893. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1810893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff, M. (2012). Bonding after trauma: On the role of social support and the oxytocin system in traumatic stress. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(1), 18597. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.18597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff, M. (2015). Mobile mental health: A challenging research agenda. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 27882. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.27882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff, M. (2017). Sex and gender differences in post-traumatic stress disorder: An update. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup4), 1351204. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1351204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olff, M., Amstadter, A., Armour, C., Birkeland, M. S., Bui, E., Cloitre, M., … Thoresen, S. (2019). A decennial review of psychotraumatology: What did we learn and where are we going? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1). doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1672948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff, M., Bakker, A., Frewen, P., Aakvaag, H., Ajdukovic, D., Brewer, D., … Elmore Borbon. (2020). Screening for consequences of trauma – An update on the global collaboration on traumatic stress. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1752504. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1752504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff, M., Langeland, W., Draijer, N., & Gersons, B. P. R. (2007). Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 133(2), 183–204. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff, M., & Schnyder, U. (2021). The global collaboration on traumatic stress. Retrieved from https://istss.org/public-resources/trauma-blog/2021-january/the-global-collaboration-on-traumatic-stress [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, M., Zhou, S. J., Guo, Z. C., Zhang, L. G., Min, H. J., Li, X. M., & Chen, J. X. (2020). The effect of social support on mental health in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(4), 514–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransing, R., Ramalho, R., Orsolini, L., Adiukwu, F., Gonzalez-Diaz, J. M., Larnaout, A., … Kilic, O. (2020). Can COVID-19 related mental health issues be measured? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 32–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, R., Socci, V., Pacitti, F., di Lorenzo, G., di Marco, A., Siracusano, A., & Rossi, A. (2020). Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. Jama Network Open, 3(5), e2010185. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, R., Socci, V., Talevi, D., Niolu, C., Pacitti, F., di Marco, A., … Olff, M. (2021). Trauma-spectrum symptoms among the Italian general population in the time of the COVID-19 outbreak. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1855888. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1855888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder, U., Schafer, I., Aakvaag, H. F., Ajdukovic, D., Bakker, A., Bisson, J. I., … Olff, M. (2017). The global collaboration on traumatic stress. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup7), 1403257. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1403257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, A. C., Williams, M. L., Amick, B. C., Hudson, T. J., & Messias, E. L. (2020). Mental health outcomes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence and risk factors in a southern US state. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113476. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L., Lu, Z. A., Que, J. Y., Huang, X. L., Liu, L., Ran, M. S., … Lu, L. (2020). Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Jama Network Open, 3(7), e2014053. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stekhoven, D. J., & Buhlmann, P. (2012). MissForest-non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics, 28(1), 112–118. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente, C., Vazquez, C., Contreras, A., Peinado, V., & Trucharte, A. (2021). A symptom-based definition of resilience in times of pandemics: Patterns of psychological responses over time and their predictors. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1871555. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1871555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer, C. A. I., Bakker, A., van Zuiden, M., Lok, A., & Olff, M. (2020). Help in hand after traumatic events: A randomized controlled trial in health care professionals on the efficacy, usability, and user satisfaction of a self-help app to reduce trauma-related symptoms. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1717155. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1717155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer, C. A. I., te Brake, H., van der Aa, N., Dashtgard, P., Bakker, A., & Olff, M. (2018). Assessing psychological resilience: Development and psychometric properties of the English and Dutch version of the Resilience Evaluation Scale (RES). Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindegaard, N., & Benros, M. E. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 89, 531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach, H. M., Murray, I., Salakhutdinov, R., & Mimno, D. (2009). Evaluation methods for topic models. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. doi: 10.1145/1553374.1553515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waters, L., Algoe, S. B., Dutton, J., Emmons, R., Fredrickson, B. L., Heaphy, E., … Steger, M. (2021). Positive psychology in a pandemic: Buffering, bolstering, and building mental health. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2021.1871945 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webb Hooper, M., Napoles, A. M., & Perez-Stable, E. J. (2020). COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(24), 2466–2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, R. G., & van der Boor, C. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and initial period of lockdown on the mental health and well-being of adults in the UK. Bjpsych Open, 6(5). doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020, March 12). A coordinated global research roadmap: 2019 novel coronavirus. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/Roadmap-version-FINAL-for-WEB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T., Jia, X., Shi, H., Niu, J., Yin, X., Xie, J., & Wang, X. (2021). Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, J. Q., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., … McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W., Chen, J. J., Perkins, R., Liu, Z., Ge, W., Ding, Y., & Zou, W. (2015). A heuristic approach to determine an appropriate number of topics in topic modeling. BMC Bioinformatics, 16(13), S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-16-S13-S8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated through the Global Collaboration on Traumatic Stress (GC-TS). Derived data of this study are available on the GC-TS website: www.global-psychotrauma.net.

The data described in this article are also openly available in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/untsy/.