Abstract

Ceramide synthase 6 (CERS6) promotes lung cancer metastasis by stimulating cancer cell migration. To examine the underlying mechanisms, we performed luciferase analysis of the CERS6 promoter region and identified the Y‐box as a cis‐acting element. As a parallel analysis of database records for 149 non–small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cancer patients, we screened for trans‐acting factors with an expression level showing a correlation with CERS6 expression. Among the candidates noted, silencing of either CCAAT enhancer‐binding protein γ (CEBPγ) or Y‐box binding protein 1 (YBX1) reduced the CERS6 expression level. Following knockdown, CEBPγ and YBX1 were found to be independently associated with reductions in ceramide‐dependent lamellipodia formation as well as migration activity, while only CEBPγ may have induced CERS6 expression through specific binding to the Y‐box. The mRNA expression levels of CERS6, CEBPγ, and YBX1 were positively correlated with adenocarcinoma invasiveness. YBX1 expression was observed in all 20 examined clinical lung cancer specimens, while 6 of those showed a staining pattern similar to that of CERS6. The present findings suggest promotion of lung cancer migration by possible involvement of the transcription factors CEBPγ and YBX1.

Keywords: CEBPγ, CERS6, lung cancer, metastasis, YBX1

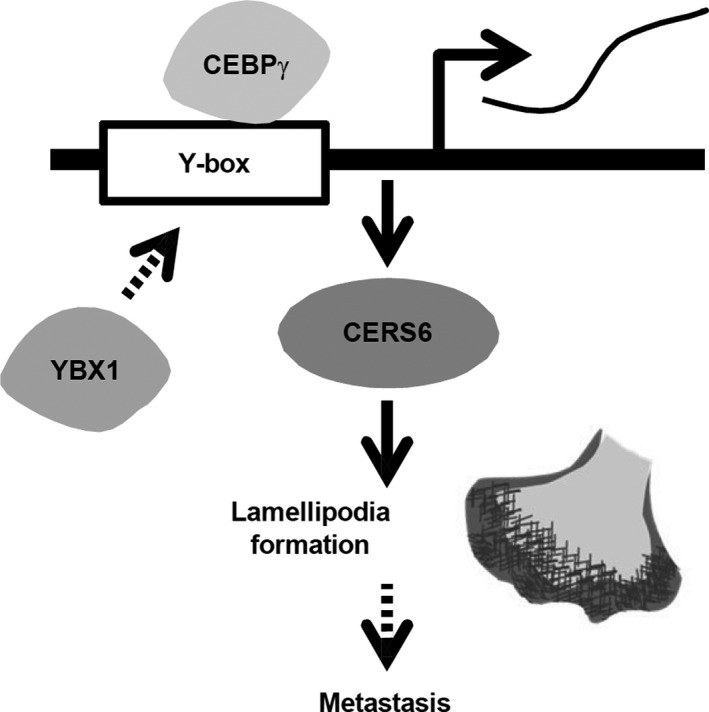

Schematic illustration showing CEBPγ functions for cancer cell migration.

Abbreviations

- C16 ceramide

d18:1‐C16:0 ceramide

- CEBPγ

CCAAT enhancer‐binding protein γ

- CERS6

ceramide synthase 6

- NSCLC

non–small‐cell lung cancer

- YBX1

Y‐box binding protein 1

1. INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death worldwide, with an estimated 1.6 million deaths each year. Despite advances in treatment options, including surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies, prognosis remains poor due to the presence of locally advanced or widely metastatic tumors. 1 , 2

The initial step of metastasis is dependent on factors related to migration and invasion, which enable cancer cells to burrow through surrounding extracellular stroma. Cell migration is associated with the formation of a cell‐structural alteration known as lamellipodia/ruffling (from this point forwards lamellipodia), which is essential for cancer cell metastasis, and induced by PKCζ activation and its complex formation with RAC1. 3 Previously, we proposed that CERS6 expression has effects on cellular ceramide constitution to upregulate the d18:1/16:0 ceramide (C16 ceramide) level, resulting in stimulation of cell migration and invasion activities through RAC1‐positive lamellipodia formation. 4

Other studies have suggested that ceramides and enzymes have roles in drug sensitivity via their metabolic pathways. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 In another study, compared with normal tissue levels, ceramide amounts were significantly increased in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) samples. 10 Furthermore, metabolic enzymes have also been reported to be modulated in acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, 11 as well as breast cancer tissues. 12 For cancer pathogenesis, ceramides are required for survival of some HNSCC cells 13 and also for cell migration activity of A549 cells by negative regulation of ceramide kinase. 14

In this study, evidence showing upregulation of CERS6 expression by the transcriptional factors CEBPγ and YBX1 is presented. YBX1 has been reported to have oncogenic functions (for review, see Evdokimova et al 15 ), while far less is known regarding the role of CEBPγ in cancer pathogenesis. To date, CEBPγ has been reported to be a regulator of cellular stress response networks and senescence, and an inflammatory suppressor, 16 as well as a transcription factor that induces myeloid differentiation arrest in acute myeloid leukemia cases. 17 We suggest that, through upregulation of CERS6 expression, CEBPγ facilitates lung cancer metastasis.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cell lines

The NCI‐H460‐LNM35 (LNM35), PC3, HEK293, and LNCaP cell lines have been previously reported. 7 , 18 , 19 These cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), unless otherwise noted, while BEAS‐2B cells, an immortalized human lung epithelial cell line, were cultured in Ham's F‐12 medium supplemented with 5 µg/mL bovine insulin, 5 µg/mL human transferrin, 100 nmol/L hydrocortisone, 0.2 nmol/L triiodine thyronine (Sigma), and 1% FBS. All cell lines were tested and confirmed to be free from Mycoplasma contamination.

2.2. Antibodies

Antibodies were purchased from the following companies: anti‐CEBPZ from Proteintech (25612‐1‐AP), anti‐NFYB (ab111577) and anti‐YBX1 (ab76149) from Abcam, anti‐NF‐YA (sc‐17753) and anti‐PKCζ (C20) (sc‐216) from Santa Cruz, anti‐CERS6 (H00253782‐M01) from Abnova, anti‐Rac1 (05‐389) from Millipore, anti‐β‐actin (A5441) from Sigma, anti‐ceramide from Glycobiotech (S58‐9), anti‐mouse (7076) and anti‐rabbit (7074) antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase from Cell Signaling Technology, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated anti‐mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 568 conjugated anti‐rabbit IgG antibodies from Invitrogen, and anti‐HA tag (clone TANA2, M180‐3) from MBL.

2.3. Plasmid construction

The transcription start site (TSS) of the CERS6 gene was determined based on 5′ RACE assay results obtained with a GeneRacer Kit (Invitrogen). For luciferase reporter assays, a series of CERS6 promoter fragments was amplified from human genomic DNA and inserted into a pGL4 vector (Promega). Two potential transcriptional factor (TF)‐binding sites, Y‐box, and GC‐box, were then mutated using a KOD Plus Mutagenesis kit (Toyobo). The primer sequences for the TSS, PCR, and mutagenesis assays are listed in Table S1.

2.4. Dual‐luciferase reporter assay

Using FuGENE 6 (Promega), LNCaP and LNM35 cells (4 × 104) were separately transfected with each reporter vector (1.95 μg) together with the Renilla control vector (0.65 μg, Promega) and cultured for 48 h in 6‐well plates. After cell lysates were prepared, luciferase reporter activities were determined using a Dual‐Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Experiments were performed in triplicate. Values are shown as the average with standard deviation (SD).

2.5. Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was carried out using Immobilon‐P filters (Millipore) and ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare). Representative data from triplicate experiments are presented unless otherwise mentioned.

2.6. Quantitative RT‐PCR (qRT‐PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using a miRNeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using a SuperScript™ VILO™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). The reaction mixture (20 μL) contained 4 μL of VILO Reaction Mix, 2 μL of SuperScript Enzyme Mix, 2.5 μg of cellular RNA, and DEPC‐treated distilled water. Incubation was carried out at 25°C for 10 min, 42°C for 60 min, and 85°C for 5 min, then SYBR green qRT‐PCR analysis was performed on a Rotor Gene 3000 system (Corbett Research), with some modifications. 20 A 20‐μL reaction mixture containing an equal amount of cDNA, 0.3 μmol/L each of forward and reverse primers (Table S1), and 12 μL of QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) was used. qRT‐PCR amplification of CEBPG was carried out for 45 cycles at 94°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. C t values were normalized to those of 18S (ΔC t), then average ΔΔC t values were calculated by normalization to the ΔC t values of siCTRL‐treated cells, as previously described. 21 Experiments were performed in triplicate. Values are shown as the average with SD.

2.7. siRNA treatment

siRNA duplexes targeting CEBPζ (siCEBPζ), CEBPγ (siCEBPγ#1 and #2), NFYA (siNFYA), NFYB (siNFYB), and YBX1 (siYBX1#1 and #2), as well as a negative control (siCTRL) were purchased from Sigma Genosys (Table S1). LNM35 and LNCaP cells were used for transfection of 20 nmol/L siRNA using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMax (Invitrogen), then cultured for 72 or 96 h, respectively. For the luciferase assay, after 24 h, siRNA‐treated cells were transfected with reporter and Renilla plasmids, and cultured for a further 48 h.

2.8. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

A ChIP assay was performed using a SimpleChIP® Enzymatic Chromatin IP kit (Cell Signaling Technology), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, with the following modifications. LNM35 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the anti‐YBX1 antibody (Abcam) and Dynabeads Co‐immunoprecipitation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PCR assays were performed as described above. Primers used to amplify regions in the genome corresponded to the predicted Y‐box in the promoter region of CERS6 or the gene desert region on chromosome 4 as a negative control (Table S1). In an experiment to detect CEBPγ, pCMV‐HA C/EBPγ (Addgene) was transfected using FuGENE 6 for 24 h prior to harvesting the cells, with the anti‐HA antibody used for immunoprecipitation. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate. Values are shown as the average with SD.

2.9. Mass spectrometric analysis

LNM35 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FBS for 24 h, then treated with siRNA for 5 h, followed by a medium exchange with RPMI 1640 medium containing N‐2 supplement (GIBCO‐BRL), then culturing was continued for 48 h. Cells were harvested and extracted in PBS, followed by protein volume measurements. After adding d18:1/C17:0‐ceramide (Avanti Polar Lipids) as the internal standard, the lipid fraction was extracted using the Bligh‐Dyer extraction method. Ceramide analysis was performed using an Acquity Ultra Performance LC system (Waters) with a 4000 QTRAP LC/MS/MS device (ABSciex). Chromatographic separations were done in a gradient mode with water/0.2% formic acid and 60% acetonitrile/40% isopropanol/0.2% formic acid solutions using a conventional ODS column (Cadenza CW‐C18, 150 × 2 mm). Mass spectrometry was performed in the positive ion mode with an electrospray ionization source. 4

2.10. Immunocytochemistry

LNM35 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FBS for 24 h, then treated with siRNA for 5‐6 h, followed by a medium exchange with RPMI 1640 medium containing N‐2 supplement (GIBCO‐BRL) with or without 1 μmol/L C16 ceramide (Avanti Polar Lipids), then culturing was continued for 48 h. After which, they were further cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 1 μmol/L C16 ceramide for 16 h. Cell staining was performed as previously described. 22

2.11. RAC1 activation assay

LNM35 cells (4.5 × 106) were used for transfection of 20 nmol/L siCEBPγ#1, siYBX1#1, siCERS6‐1, or negative control siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMax. After culturing the cells for 6 h in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FBS, the medium was replaced with RPMI 1640 medium containing an N‐2 supplement (GIBCO‐BRL), then the culture was continued for 2 d, followed by serum stimulation using RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS for 16 h. RAC1 activation assays were performed using a Rac1/Cdc42 Activation Assay Kit (Millipore). Briefly, cells were harvested and dissolved in Mild Lysis Buffer (MLB) (125 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.5, 750 mmol/L NaCl, 5% Igepal CA‐630, 50 mmol/L MgCl2, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 10% glycerol), then centrifuged at 14 000 × g for 15 s. Thereafter, PAK‐1 PBD agarose beads were incubated with each supernatant at 4°C for 1.5 h, then washed 3 times with MLB and binding proteins. Western blotting analysis was then performed.

2.12. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed using BOND RX (v. 5.2) and a BOND Polymer Refine Detection system (Leica), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated in ethanol. After antigen retrieval performed with BOND Epitope Retrieval Solution 2 (Leica), the sections were incubated with the anti‐CERS6 or anti‐YBX1 antibody for 15 min at room temperature, followed by a rinse with BOND wash solution (Leica) and the blocking solution for 8 min. Endogenous peroxidase was inactivated in methanol containing 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min at room temperature. Following another rinse, reaction products were visualized by placing in 50 mmol/L Tris‐HCl buffer, pH 7.6, containing 20 mmol/L diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride, and 0.1% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min. Nuclei were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin.

2.13. Cell viability assays

LNM35 cells were plated at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/2 mL and cultured for 24 h. After treatment with siRNAs, the cells were further cultured for 72 h. Numbers of viable cells were determined using a Cell Counting Kit‐8 (Doujindo Laboratories), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

2.14. Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using a two‐tailed t test, Pearson's product‐moment correlation coefficient, and Fisher exact test. Clinical analyses were done using the GSE11969 dataset. 23

2.15. Ethical approval

Requisite approval was obtained from the review boards of Fujita Health University School of Medicine (HG18‐042) and Nagoya University School of Medicine (2017‐0034). Written informed consent from the patients was obtained prior to obtaining human samples. The recombinant DNA experiment protocols were also approved by the review board of Fujita Health University School of Medicine (DP17021).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Y‐box used for CERS6 transcriptional activation

Findings showing altered expressions of ceramides and CERS family proteins in malignant tumors have been reported. 10 , 12 , 24 , 25 Among CERS family proteins, a high expression level of CERS6 was shown to be associated with metastatic features as well as poor prognosis. 4

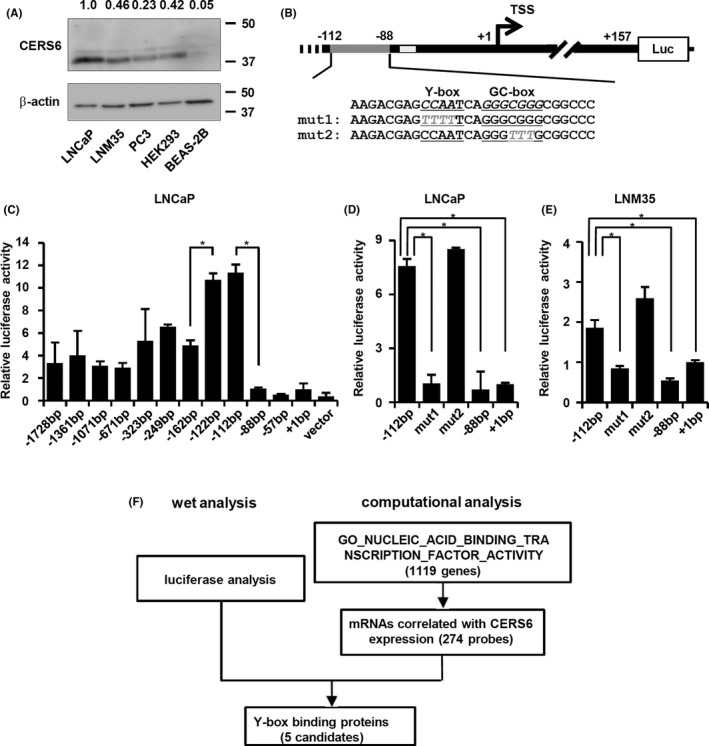

CERS6 expression is controlled by miR101, a tumor suppressor miRNA, 4 or CERS6‐AS1, a lincRNA, 26 although other regulatory mechanisms are not well understood. We screened for cis‐acting elements in the promoter region using prostate cancer LNCaP cells and found those to be associated with elevated CERS6 expression (Figure 1A). Analysis to determine TSSs showed that those located at 157 and 221 bases upstream from the 1st exon, which are close to, but not the same as, a previously reported TSS (Figure S1). In analyses following those results, luciferase constructs using the −1728 bp, which contains the CERS6 promoter region between −1728 and +157 (Figure 1B), to −162 bp regions showed similar promoter activities, whereas those using the −122 bp and −112 bp regions were associated with only a moderate increase and those using the −88 bp to +1 bp regions were associated with a significant decrease (Figure 1C), suggesting the presence of positive element(s) between the −112 and −88 regions.

FIGURE 1.

Y‐box may positively regulate CERS6 expression. A, Western blot analysis results of CERS6 levels in a cancer cell line panel. CERS6 expression was quantitated as relative to β‐actin and is shown with LNCaP as a value of 1. B, Schematic illustration of insert regions of luciferase plasmids, each of which contains an insert between the indicated position and +157 promoter region. For mut1 and mut2, base substitutions in the Y‐ and GC‐boxes are shown. TSS, transcription start site; Luc, luciferase gene; dark gray line,−112 to −88 positions; light gray line, putative p53 binding site. C‐E, Luciferase activities were examined using the indicated plasmids. Data are shown as relative values to a +1 bp construct (mean ± SD) (n = 3). LNCaP and LNM35 cells were used for the analyses. *P < .05. (F) Filtering methods to screen for putative Y‐box binding proteins using the GSE 11969 clinical dataset

We introduced base substitutions in each of the 2 putative cis‐elements, ie, Y‐ and GC‐boxes (Figure 1B), and performed luciferase analysis. In both LNCaP and the LNM35 lung cancer cell line, disruption of the Y‐box sequence resulted in significantly reduced promoter activities, while disruption of the GC‐box did not have such an effect (Figure 1D,E).

3.2. CEBPγ and YBX1 upregulate CERS6 expression

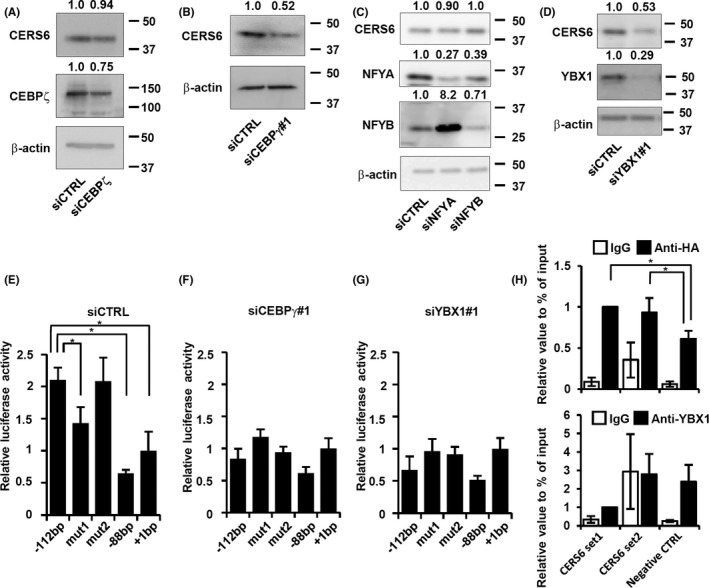

Parallel analysis using a clinical dataset was used to screen for transcriptional factors with gene expression profiles correlated with CERS6. Among the genes that showed significant correlations, 5 coded Y‐box binding proteins were noted (Figures 1F and S2, and Table 1). To investigate whether CERS6 expression is controlled by any of those gene products, each was knocked down and CERS6 expression was examined (Figures 2A‐D and S3A). Following separate siRNA treatments with CEBPγ and YBX1, the CERS6 expression level was decreased in LNM35 cells, while the effect of CEBPζ, NFYA, or NFYB suppression seemed to be only marginal or increased. Similar results were obtained with LNCaP (Figures S3B and S4A‐D) as well as other siRNAs with independent sequences (Figure S4E,F), while cell viability seemed to be less affected by siCEBPγ or siYBX1 under the present experimental conditions (Figure S3C).

TABLE 1.

Correlations between putative Y‐box transcription genes and CERS6 expression levels

| R value | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|

| CEBPZ | 0.55 | 2.4 × 10−13 |

| CEBPG | 0.44 | 8.4 × 10−9 |

| NFYB | 0.43 | 3.3 × 10−8 |

| NFYA | 0.31 | 7.0 × 10−5 |

| YBX1 | 0.27 | 7.5 × 10−4 |

Correlations between Y‐box transcription genes and CERS6 expressions are shown. Transcription genes with an R value >0.2 are shown.

FIGURE 2.

CERS6 expression in LNM35 cells regulated by CEBPγ and YBX1. Western blot analysis results showing CERS6 protein level after silencing of (A) CEBPζ, (B) CEBPγ, (C) NFYA and NFYB, and (D) YBX1. CEBPG expression levels were measured using an RT‐PCR assay (Figure S3A), as no reliable antibody could be found. Luciferase reporter analysis results with (E) siCTRL, (F) siCEBPγ#1 and (G) siYBX1#1. Values are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < .05. (H) ChIP assays performed with anti‐HA and anti‐YBX1 antibodies using LNM35 cells. Values are shown as the mean ± SD (n = 4). *P < .05

Furthermore, the suppressive effect of the Y‐box mutation seemed to be neutralized in siCEBPγ‐ or siYBX1‐treated cells (Figure 2E‐G), suggesting that CEBPγ and YBX1 directly or indirectly interacted with Y‐box.

Results of a ChIP assay showed that the anti‐HA antibody precipitated a greater number of CERS6 promoter regions compared with the control, indicating specific binding between CEBPγ and Y‐box. In addition to this specific activity, CEBPγ may have general DNA binding activity because, irrespective of the primer sets used, the anti‐HA antibody precipitated greater numbers of target regions compared with the IgG controls (Figure 2H, top). Conversely, our analysis showed only non‐specific binding activity for YBX1 (Figure 2H, bottom). Together, these findings suggested that CEBPγ upregulates CERS6 via specific binding to the Y‐box, while YBX1 may exert Y‐box interaction through one or more other factors.

Additional experiments were performed to determine whether YBX1 upregulated CERS6 through modulation of CEBPγ expression. In this analysis, neither siRNA‐induced reduction of CEBPγ nor YBX1 had effects on the expression level of the other (Figure S5A), indicating that YBX1 does not stimulate CERS6 expression via CEBPγ upregulation or vice versa.

We further attempted to determine whether both transcription factors are required to activate the promoter or whether one is adequate, but endogenous protein levels are too low to activate the promoter. For this analysis, we knocked down YBX1 and overexpressed CEBPγ‐HA, evaluated CERS6 expression levels, and found that under this particular condition CERS6 expression was again suppressed (Figure S5B). Together, these results suggested that the presence of only one of these transcription factors is not adequate, but rather both are required for activation of the promoter.

3.3. Effects on RAC1‐positive lamellipodia formation

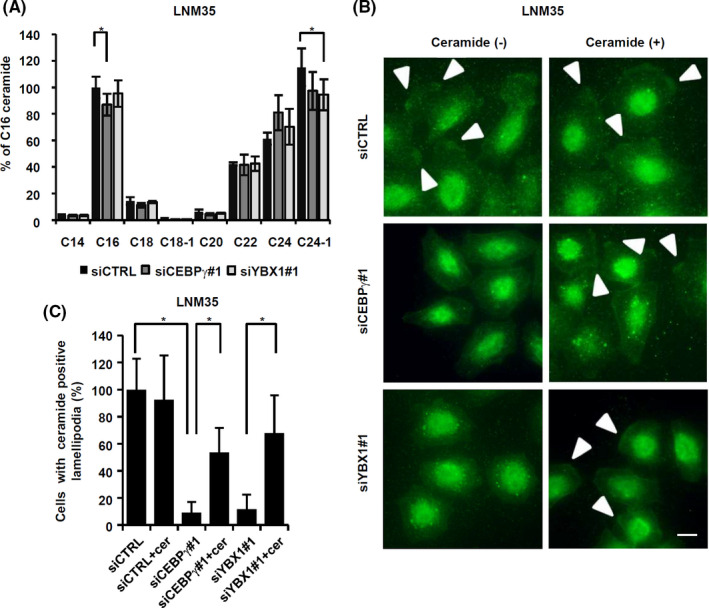

CERS6 is an enzyme that produces C16 ceramide. To understand whether CEBPγ and YBX1 have effects on C16 ceramide levels through regulation of CERS6 expression, MS analysis was performed under knockdown conditions. CEBPγ knockdown consistently reduced the amount of C16 ceramide, whereas the effect of YBX1 knockdown was not significant (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Ceramide synthesis may contribute to migration activity and lamellipodia formation. A, Relative ceramide amounts were determined in LNM35 cells (n = 6). The experiment was replicated and similar results were obtained in each. *P < .05. B, At 12 h after serum stimulation, cells were fixed and stained with an anti‐ceramide antibody. Bar, 10 μm. Arrowheads, lamellipodia. C, In groups of 100 cells or more, those with ceramide‐positive lamellipodia were counted and the results plotted as values relative to siCTRL. Values (mean ± SD) from quintuplicate experiments are shown. *P < .05

MS analysis was used to examine whole‐cell ceramides. Therefore, in the next experiments, cells were stained with an anti‐ceramide antibody and then ceramide amounts in microstructures were visualized. The results showed that knockdown of either CEBPγ or YBX1 reduced lamellipodia ceramide levels, while the phenotypes were partially rescued by ectopic addition of C16 ceramide (Figure 3B,C). These findings suggested that both CEBPγ and YBX1 had effects on ceramide levels through CERS6 expression in lamellipodia structures.

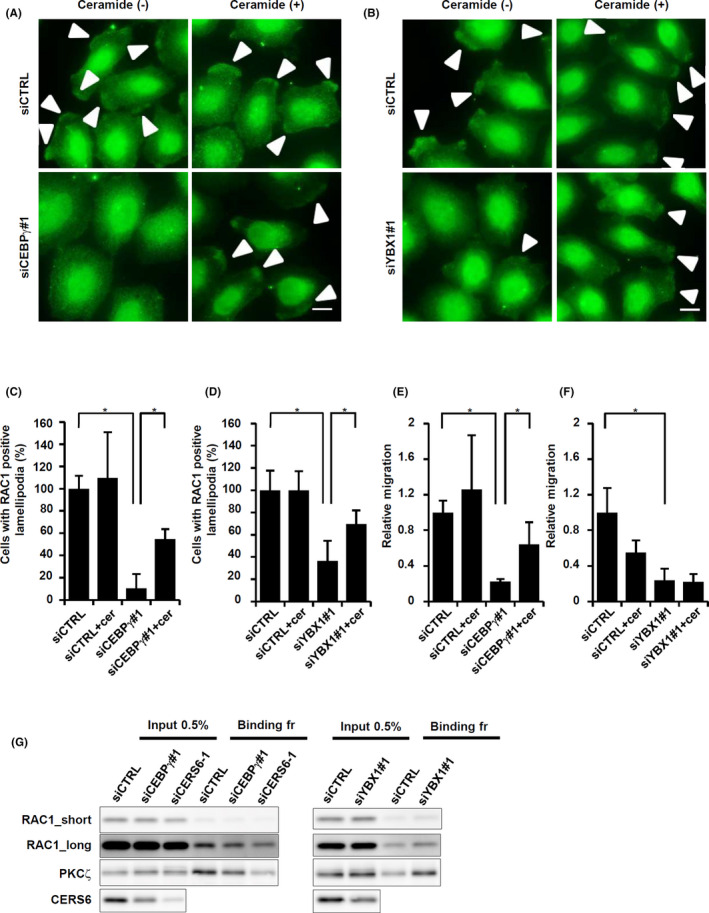

CERS6 stimulates cell migration through RAC1‐positive lamellipodia formation. 4 Lamellipodia formation is induced by activation of ceramide‐dependent PKCζ and the resultant complex formation with RAC1. 3 In this context, the effects of CEBPγ and YBX1 expression on lamellipodia formation efficiency were further quantitated by determining RAC1 and PKCζ positivity. In LNM35 cells, siRNA treatment against either one of the transcriptional factors reduced RAC1‐positive lamellipodia formation, which was partially rescued by C16 ceramide (Figure 4A‐D). Similar results were obtained in experiments using PKCζ as a lamellipodia marker (Figure S6).

FIGURE 4.

Lamellipodia formation in LNM35 cells. A, siCEBPγ‐treated LNM35 cells were used for immune cytochemistry for RAC1 by culturing in the presence or absence of ectopic 1 μmol/L C16 ceramide. Arrowheads, lamellipodia. Scale bar, 10 μm. B, siYBX1#1‐treated cells were used for immune cytochemistry for RAC1 by culturing in the presence or absence of ectopic C16 ceramide. Arrowheads, lamellipodia. Scale bar, 10 μm. Quantitative results are also shown in (C) and (D) as values relative to siCTRL. Values were obtained by counting 100 or more cells and are shown as the mean ± SD. *P < .05. Experiments were repeated 3 times. E, LNM35 cells were treated with siCEBPγ, then migration activities were examined with or without 1 μmol/L C16 ceramide. F, LNM35 cells were treated with siYBX1#1, then migration activities were determined with or without 1 μmol/L C16 ceramide. Experiments were repeated 3 times. G, LNM35 cells were treated with siCTRL, siCEBPγ#1, siYBX1#1 or siCERS6‐1, and then analyzed for the presence of the active RAC1 complex. Input and bound fractions were subjected to western blotting analyses of RAC1, PKCζ, and CERS6

Interestingly, under the same rescue conditions, migration activities were partially recovered in a dose‐dependent manner when the cells were treated with siCEBPγ and C16 ceramide (Figures 4E and S7), while no such rescue phenotype was observed with the combination of siYBX1 and C16 ceramide (Figure 4F).

The involvement of CEBPγ as an upstream regulator of CERS6 was further examined by use of a biochemical method (Figure 4G). Knockdown of either CEBPγ or CERS6 in LNM35 cells was found to be associated with a decreased amount of active RAC1 protein. Accordingly, PKCζ was co‐precipitated with active RAC1, with the amount decreased in CEBPγ‐knockdown cells. Knocking down of another transcription factor YBX1 was associated with an increase in RAC1 and PKCζ, again suggesting a possibility that YBX1 regulates not only CERS6 but also other factors.

These results indicated that both lamellipodia formation and migration activity are, at least in part, dependent on CEBPγ expression. Furthermore, YBX1, another transcription factor, may also positively regulate lamellipodia formation but not migration activity.

3.4. Associations with clinical features

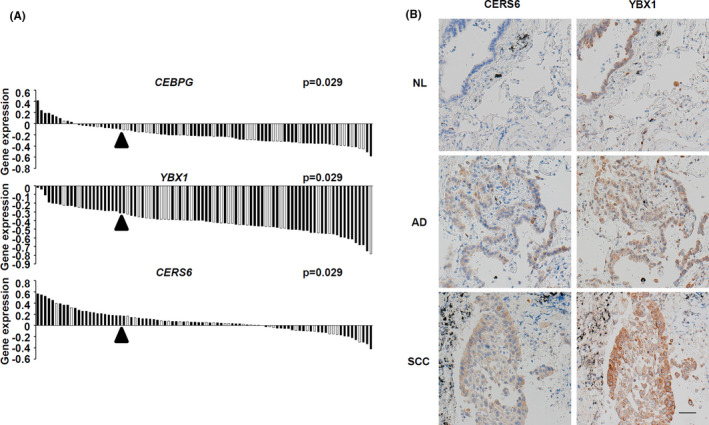

To determine whether CEBPγ, YBX1, and the putative downstream factor CERS6 promoted cancer cell migration in patients, a clinical dataset containing information for 90 adenocarcinoma patients was analyzed. Those results showed that the expression level of each of those genes was significantly associated with the degree of invasiveness (Figure 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Gene expression levels and invasion status. A, Correlations between gene expression and invasion status are shown. In each panel, gene expression levels in adenocarcinoma patients are shown as a waterfall plot, with each patient column associated with invasion status information shown as ++ (black) or + ~ – (white). Arrowheads indicate the threshold to classify the high (top quartile) and low (others) groups for each gene. For all genes, the expression‐high groups were significantly associated with the invasive phenotype. P‐values were determined using Fisher exact test. B, Representative images showing CERS6 and YBX1 expression in lung cancer specimen. AD, adenocarcinoma; NL, tumor adjacent normal tissue; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma. Scale bar, 50 μm

We also analyzed the expression of CERS6 and YBX1 proteins in clinical patients. In accordance with previous results, 4 CERS6 expression was observed in lung cancer cells at levels that varied among the patients (Figure 5B and Table S3). Furthermore, YBX1 expression was observed in all 20 of the clinical lung cancer specimens, with expression patterns homogeneous in 14. Interestingly, in the other 6 cases, the YBX1 patterns were heterogenous and similar to those of CERS6. These results led us to speculate that YBX1 is one of the positive regulators of CERS6 expression.

4. DISCUSSION

The present results demonstrated that CERS6 expression is regulated by CEBPγ. Altered expression of CEBPγ mRNA, as well as changes in antioxidant, DNA repair, and transcription factor genes have been identified in normal bronchial epithelial cells obtained from bronchogenic carcinoma patients. 27 , 28 In the field of hematology, CEBPγ overexpression is known to be associated with acute myeloid leukemia, 17 while its rearrangement is associated with B‐cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. 29 Outside of those studies, very little information is known regarding the onco‐pathological functions of CEBPγ. Therefore, this study provided novel evidence suggesting that CEBPγ is a potential factor for promotion of lung cancer metastasis. In relation to our results, it should also be noted that a very recent manuscript has reported that CEBPγ promotes esophageal squamous cell progression and migration activity. 30

We also found that YBX1 is involved in transcriptional regulation of CERS6. As an oncogenic transcription factor, YBX1 is regarded as a predictive and prognostic marker in malignant cancer, 31 , 32 , 33 as well as a factor in stimulation of migration (for review, see Evdokimova et al 15 ). In this regard, the present findings showed that ceramide does not rescue migration in siYBX1‐treated cells, but rather contributes to a specific phase of the lamellipodia formation phenotype (Figure 4B,D,F). These results are consistent with previous findings showing that YBX1 regulates the number of motility‐related proteins and further suggests a novel pathway for YBX1 that produces, at least in a part, oncological effects through expression of CERS6‐induced lamellipodia formation.

Immunohistochemistry analysis showed that YBX1 is a positive regulator of CERS6 expression, although in some normal cells, such as pseudo‐stratified ciliated epithelium cells, as well as some cancer cells only YBX1 expression was observed. These results suggested the presence of negative regulators. Along this line, findings in our prior study showed that expression levels of the tumor suppressor miR‐101 were negatively correlated with those of CERS6 in both clinical cancer and normal tissues, and that it directly suppressed CERS6 levels. 4 Therefore we considered that multiple factors are used in tuning the level of CERS6 expression to regulate the multiple steps involved in development of a metastatic phenotype in lung cancer.

Based on these and other related results, we propose that the transcription factor CEBPγ promotes CERS6 expression via a specific interaction with the Y‐box, and that it also regulates lamellipodia formation and migration activity (Figure 6). YBX1, another transcription factor, may also be involved in this pathway. Results of the present in vitro experiments and clinical data analysis, as well as findings in our previous study showing that CERS6 promotes cancer metastasis 4 appear to be consistent with the hypothesis that CEBPγ upregulates cancer metastasis. However, the possibility that CEBPγ has metastasis suppression activity through one or more unidentified pathways cannot be denied. Additional experiments are required to establish the presence of a direct link between this particular transcription factor and cancer metastasis.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic illustration showing CEBPγ and YBX1 functions related to lamellipodia formation

In a related study, CERS6 was reported to be a transcriptional target of p53 protein activation in response to folate stress. 34 In the present constructs, the putative p53 binding site was located between the −69 to −56 positions (Figure 1B). Consistently, luciferase activity using a −57 bp construct was lower than that with use of a −88 bp construct, although the extent of cis‐acting activity seemed to be lower than that occurring between −112 and −88 bp (Figure 1C). Furthermore, p53 and CERS6 expression showed a negative correlation in clinical NSCLC specimens (Figure S8 and Table S2). Therefore, CERS6 regulation by p53 seems to be auxiliary in the absence of folate stress.

In summary, the present results suggested that CEBPγ, together with YBX1, function as transcriptional factors to promote lung cancer metastasis through upregulation of CERS6 expression. Additional studies for elucidating mechanisms related to metastasis promotion will contribute to identifying molecular targets as well as the development of drugs to control this mortal cancer phenotype in affected patients.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Figures S1‐S8

Table S1‐S3

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a Grant‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. We thank Chiharu Okajima and Yuko Mizuno at Nagoya University and Mika Maeshima at Fujita Health University for their helpful technical assistance.

Shi H, Niimi A, Takeuchi T, et al. CEBPγ facilitates lamellipodia formation and cancer cell migration through CERS6 upregulation. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:2770–2780. 10.1111/cas.14928

REFERENCES

- 1. Altorki NK, Markowitz GJ, Gao D, et al. The lung microenvironment: an important regulator of tumour growth and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:9‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non‐small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553:446‐454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xiao H, Liu M. Atypical protein kinase C in cell motility. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:3057‐3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Suzuki M, Cao K, Kato S, et al. CERS6 required for cell migration and metastasis in lung cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:11949‐11959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aoyama Y, Sobue S, Mizutani N, et al. Modulation of the sphingolipid rheostat is involved in paclitaxel resistance of the human prostate cancer cell line PC3‐PR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486:551‐557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ito H, Murakami M, Furuhata A, et al. Transcriptional regulation of neutral sphingomyelinase 2 gene expression of a human breast cancer cell line, MCF‐7, induced by the anti‐cancer drug, daunorubicin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:681‐690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mizutani N, Inoue M, Omori Y, et al. Increased acid ceramidase expression depends on upregulation of androgen‐dependent deubiquitinases, USP2, in a human prostate cancer cell line, LNCaP. J Biochem. 2015;158:309‐319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mizutani N, Omori Y, Kawamoto Y, et al. Resveratrol‐induced transcriptional up‐regulation of ASMase (SMPD1) of human leukemia and cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;470:851‐856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sobue S, Nemoto S, Murakami M, et al. Implications of sphingosine kinase 1 expression level for the cellular sphingolipid rheostat: relevance as a marker for daunorubicin sensitivity of leukemia cells. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:266‐275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karahatay S, Thomas K, Koybasi S, et al. Clinical relevance of ceramide metabolism in the pathogenesis of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC): attenuation of C(18)‐ceramide in HNSCC tumors correlates with lymphovascular invasion and nodal metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2007;256:101‐111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sobue S, Iwasaki T, Sugisaki C, et al. Quantitative RT‐PCR analysis of sphingolipid metabolic enzymes in acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2006;20:2042‐2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Erez‐Roman R, Pienik R, Futerman AH. Increased ceramide synthase 2 and 6 mRNA levels in breast cancer tissues and correlation with sphingosine kinase expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:219‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Senkal CE, Ponnusamy S, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, Ogretmen B. Antiapoptotic roles of ceramide‐synthase‐6‐generated C16‐ceramide via selective regulation of the ATF6/CHOP arm of ER‐stress‐response pathways. FASEB J. 2010;24:296‐308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tomizawa S, Tamori M, Tanaka A, et al. Inhibitory effects of ceramide kinase on Rac1 activation, lamellipodium formation, cell migration, and metastasis of A549 lung cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2020;1865:158675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evdokimova V, Tognon C, Ng T, Sorensen PH. Reduced proliferation and enhanced migration: two sides of the same coin? Molecular mechanisms of metastatic progression by YB‐1. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2901‐2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huggins CJ, Mayekar MK, Martin N, et al. C/EBPgamma is a critical regulator of cellular stress response networks through heterodimerization with ATF4. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;36:693‐713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alberich‐Jorda M, Wouters B, Balastik M, et al. C/EBPgamma deregulation results in differentiation arrest in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4490‐4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kozaki K, Miyaishi O, Tsukamoto T, et al. Establishment and characterization of a human lung cancer cell line NCI‐H460‐LNM35 with consistent lymphogenous metastasis via both subcutaneous and orthotopic propagation. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2535‐2540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kikuchi R, Sobue S, Murakami M, et al. Mechanism of vitamin D3‐induced transcription of phospholipase D1 in HaCat human keratinocytes. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1800‐1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mizutani Y, Tsuge S, Takeda H, et al. In situ visualization of plasma cells producing antibodies reactive to Porphyromonas gingivalis in periodontitis: the application of the enzyme‐labeled antigen method. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2014;29:156‐173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang QM, Tomida S, Masuda Y, et al. Regulation of DNA polymerase POLD4 influences genomic instability in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8407‐8416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hosono Y, Yamaguchi T, Mizutani E, et al. MYBPH, a transcriptional target of TTF‐1, inhibits ROCK1, and reduces cell motility and metastasis. EMBO J. 2012;31:481‐493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takeuchi T, Tomida S, Yatabe Y, et al. Expression profile‐defined classification of lung adenocarcinoma shows close relationship with underlying major genetic changes and clinicopathologic behaviors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1679‐1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang H, Wang J, Zuo Y, et al. Expression and prognostic significance of a new tumor metastasis suppressor gene LASS2 in human bladder carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2012;29:1921‐1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu XY, Pei F, You JF. TMSG‐1 and its roles in tumor biology. Chin J Cancer. 2010;29:697‐702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bao G, Huang J, Pan W, Li X, Zhou T. Long noncoding RNA CERS6‐AS1 functions as a malignancy promoter in breast cancer by binding to IGF2BP3 to enhance the stability of CERS6 mRNA. Cancer Med. 2020;9:278‐289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blomquist T, Crawford EL, Mullins D, et al. Pattern of antioxidant and DNA repair gene expression in normal airway epithelium associated with lung cancer diagnosis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8629‐8635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mullins DN, Crawford EL, Khuder SA, Hernandez DA, Yoon Y, Willey JC. CEBPG transcription factor correlates with antioxidant and DNA repair genes in normal bronchial epithelial cells but not in individuals with bronchogenic carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Akasaka T, Balasas T, Russell LJ, et al. Five members of the CEBP transcription factor family are targeted by recurrent IGH translocations in B‐cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP‐ALL). Blood. 2007;109:3451‐3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang Y, Lin L, Shen Z, et al. CEBPG promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma progression by enhancing PI3K‐AKT signaling. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:3328‐3344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson TG, Schelch K, Cheng YY, et al. Dysregulated expression of the MicroRNA miR‐137 and its target YBX1 contribute to the invasive characteristics of malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:258‐272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lu J, Li X, Wang F, et al. YB‐1 expression promotes pancreatic cancer metastasis that is inhibited by microRNA‐216a. Exp Cell Res. 2017;359:319‐326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Y, Chen Y, Geng H, Qi C, Liu Y, Yue D. Overexpression of YB1 and EZH2 are associated with cancer metastasis and poor prognosis in renal cell carcinomas. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:7159‐7166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fekry B, Jeffries KA, Esmaeilniakooshkghazi A, Ogretmen B, Krupenko SA, Krupenko NI. CerS6 is a novel transcriptional target of p53 protein activated by non‐genotoxic stress. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:16586‐16596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1‐S8

Table S1‐S3