Abstract

Therapies used to tide over acute crisis of COVID-19 infection may lower the immunity, which can lead to secondary infection or a reactivation of latent infection. We report a 75-years-old male patient who had suffered from severe COVID-19 infection three weeks earlier and who had been treated with corticosteroids and convalescent plasma along with other supportive therapies. At time of discharge he had developed leukopenia which worsened at 1-week follow up visit. On 18th day post-discharge, he became very sick and was brought to our hospital with complaints of severe persistent dysphagia. During evaluation he was diagnosed to have an acute cytomegalovirus infection and severe oropharyngeal thrush. Both COVID-19 and cytomegalovirus are known to cause synergistic decrease in T cells and NK cells leading to immunosuppression. The patient made complete recovery with a course of intravenous ganciclovir and fluconazole. Persistent leukopenia in high risk and severely ill cases should give rise to a suspicion of COVID-19 and cytomegalovirus co-infection.

KEY WORDS: Convalescent plasma, COVID-19, cytomegalovirus infection, leukopenia

Introduction

COVID-19 pandemic has posed many challenges to the medical fraternity. As the epidemic unfolds, new facets of COVID-19 are being revealed. We report a patient recovering from COVID-19 who presented to us with persistent leukopenia which was attributed to recent cytomegalovirus co-infection. As there is paucity of literature on co-infection of COVID-19 and cytomegalovirus, this case is important as it discusses the mechanism, evaluation, management, and its possible impact on outcome of high risk and severely ill cases.

Case Report

A 75-year-old male, a known case of hypertension, had flu-like illness for past four days. He tested positive for COVID-19 by RT PCR and was admitted in ICU of a healthcare facility. His routine investigations such as CBC, LFT, RFT, and baseline ECG were all within normal limits. His inflammatory markers were raised. He was treated with injectable methylprednisolone, high oxygen supportive therapy and trials of different adjunctive medications such as hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin over time. He experienced severe dyspnoea, tachypnoea, and his oxygen requirement remained high despite treatment. His repeat ECG was normal and chest X-ray showed new opacities in bilateral lung fields. He was administered a five-day course of remdesivir and two sessions of convalescent plasma therapy. His condition improved and was discharged after he tested COVID negative about three weeks later. His steroid medications were tapered over next one week. He was found to have significant leukopenia (2.80 × 103 per micro L) on follow up after a week, which decreased further (2.00 × 103 per micro L) in next five days for which he was advised vitamin B12 supplements.

On eighteenth day post discharge, he became very sick and was brought to our hospital with complaints severe persistent dysphagia to both solids and liquids since past three days. Patient was drowsy on presentation but was arousable by verbal commands. Once his cardiac evaluation was found to be acceptable by Cardiac Care Unit of our facility, he was shifted to Medicine unit for further evaluation. Patient was febrile, toxic looking and vitals were stable. On oral examination he had severe oropharyngeal thrush. Initial investigations showed persistence of leukopenia as seen in the reports of past two weeks. TLC on admission was 2.13 × 103 per micro L with Absolute Neutrophil count-1534 per micro L and Absolute Lymphocyte count-362 per micro L. In addition, there was hyponatremia. Other routine tests were normal. COVID Rapid Antigen test and RT PCR was negative, but Total COVID antibody test was mildly positive (11 units). Serum procalcitonin was 0.09 ng/mL. Viral markers for hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV were negative. After correction of electrolyte abnormality, patient became alert and interactive. Patient was treated with intravenous fluconazole and local application of clotrimazole mouth paint for oral thrush along with all the measures to ensure oral hygiene.

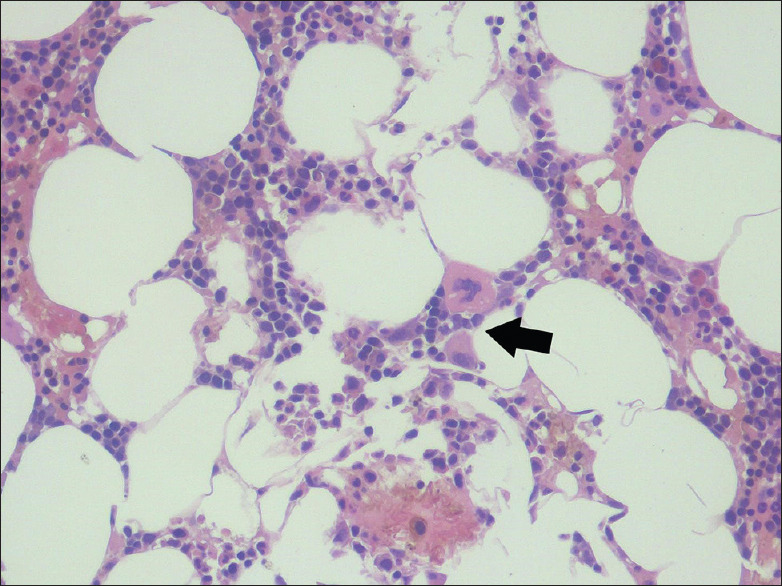

Patient was evaluated for the cause of unexplained leukopenia. Peripheral smear, bone marrow aspiration, and biopsy were not contributory [Figure 1]. T, B, & NK panel showed CD3+/CD4+ cells 196 per micro L (Normal range: 443-1345), CD3+/CD8+ cells 92 per micro L (Normal range: 171-194) and CD 56+ CD16 (NK cells) 51 per micro L (Normal range: 80-662). With a single dose of G-CSF injection TLC improved to 3.70 × 103 /micro L.

Figure 1.

Bone marrow biopsy: Normocellular for age with megaloblastic erythropoiesis, mature megakaryocytes and relatively reduced myeloid elements with histiocytic predominance (arrow)

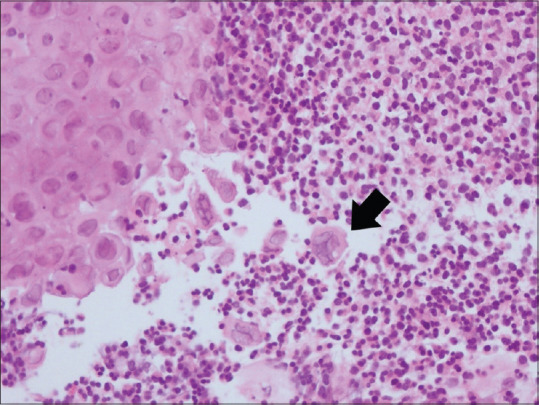

Upper GI endoscopy revealed severe esophagitis and multiple shallow geographical ulcers. Biopsy was taken from the ulcer margin and microscopic morphological picture features were suggestive of a viral aetiology [Figure 2]. RT PCR test for cytomegalovirus from the tissue biopsy sample and blood was positive. IgM serology test for herpes virus was negative. Antibody test for cytomegalovirus showed titre of 217 AU/mL, with intermediate avidity implicating a recent and active infection, possibly a co-infection with SARS CoV-2 resulting in immunosuppression that later manifested as opportunistic oropharyngeal thrush. The patient improved clinically and blood counts reached the normal range within five days of initiating treatment with intravenous ganciclovir.

Figure 2.

Oesophageal ulcer biopsy: Focal ulceration surrounded by neutrophil rich inflammatory infiltrate. Dyscohesive squamous cells are seen. Some of them are enlarged with nucleomegaly and many bi and multinucleated cells (arrow). These show dense eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions

Discussion

Most prominent haematological feature of COVID-19 is absolute lymphopenia with neutrophilic predominance and high neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR). It is directly proportional to the severity of disease.[1] NLR ratio in the present case was 4.23 (normal 1-3). Similar lymphopenia is also observed in various other respiratory viral illnesses. However, in contrast to these illnesses it has been observed that COVID-19 causes persistent lymphopenia.

T cell subsets, especially CD8+ T lymphocytes are affected which can be attributed to either excessive recruitment to the vascular channels and respiratory tracts or hyperactivation of the T cells by IL6, IL10, TNF alpha, and other inflammatory cytokines.[2] It has also been observed that in these subsets there is increased expression of extrinsic pathway of pro-apoptotic signals (caspase 3 and CD95).[3] Emerging evidence indicates that the lymphocyte, CD 3+, CD4+ and CD8+ could fall as low as one third to two third of their median values and that the patients with low CD4+ T cells have worse prognosis in comparison to those with CD8+ T lymphopenia.[4]

Steroids which are often used to tide over an acute crisis in moderate to severe COVID-19 cases can be another possible cause of leukopenia observed in these cases. But studies are showing that fall in numbers due to steroids recovers promptly unlike in the present case.[5] Immunosuppressants causing reactivation of a latent infection or plasma therapy acting as a source for a new infection can be two important risk factors for possible coinfections in COVID-19. A case of coinfection of cytomegalovirus and COVID-19 with leukopenia at presentation was reported that concluded that immunosuppression was possibly the best explanation for the co-infection.[6]

It has been observed that cytomegalovirus seropositivity is significantly associated with mortality of SARS CoV-2. It activates the peripheral T cells and NK cells leading to marked decrease in naïve T cells which adds on to the insult of SARS CoV-2 to the T lymphocytes. It has been reported that cytomegalovirus reactivation causes accelerated attrition of naïve T cells by multiple mechanisms like memory inflation and thus leading to failed response of the body to novel coronavirus.[7] As cytomegalovirus resides in myeloid lineage, change in activation of macrophages in response to SARS CoV-2 increases severity of the infection.

A cytomegalovirus screening in all the high-risk patients and in ICU setting with persistent leukopenia might help in reducing the percentage and degree of mortality and complications the patient might suffer from. A recent study has reported benefit of hyperimmune anti CMV globulin over the conventional plasma therapy for COVID-19 cases coinfected with cytomegalovirus.[8] This may open up a whole new dimension for the way high risk and severe COVID-19 cases are diagnosed and managed. The following observations highlight the need for an exhaustive research on coinfection of COVID-19 and cytomegalovirus and possibly an eye on other superinfections.

The suspicion of a possible cytomegalovirus coinfection in the present case was based on the microscopic morphological picture of the oesophageal biopsy such as enlargement of cells with nucleomagaly and eosinophilic inclusion bodies based on the histologic criteria.[9] It was confirmed with a positive RT PCR test from the tissue sample. Lymphopenia has been identified as the most common risk factor development of oropharyngeal candidiasis in COVID-19 patients in a recent study.[10] The temporal relationship of events which occurred in our case, is highly suggestive of a coinfection with cytomegalovirus resulting in severe leukopenia with subsequent development of oropharyngeal thrush. Lymphopenia improved drastically within 4 to 5 days of starting ganciclovir.

Conclusion

Although leukopenia is commonly seen in COVID-19 cases, persistent leukopenia especially in elderly may warrant further evaluation especially for co-infection with cytomegalovirus as it acts as a negative risk factor for outcome of these cases.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that appropriate patient consent was obtained.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Aditi Kundoo for general support and sharing the bone marrow biopsy image; and Dr. Sunila Jain for sharing the oesophageal biopsy image.

References

- 1.Violetis O, Chasouraki A, Giannou A, Baraboutis I. COVID-19 infection and haematological involvement: A review of epidemiology, pathophysiology and prognosis of full blood count findings. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;29:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00380-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terpos E, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Elalamy I, Kastritis E, Sergentanis T, Politou M, et al. Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:834–47. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Z, John Wherry E. T cell responses in patients with COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:529–36. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0402-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathew D, Giles J, Baxter A, Oldridge D, Greenplate A, Wu J, et al. Deep immune profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications. Science. 2020;369:eabc8511. doi: 10.1126/science.abc8511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baraboutis I, Gargalianos P, Aggelonidou E, Adraktas A Collaborators. Initial real-life experience from a designated COVID-19 centre in Athens, Greece: A proposed therapeutic algorithm. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00324-x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Ardes D, Boccatonda A, Schiavone C, Santilli F, Guagnano M, Bucci M, et al. A case of coinfection with SARS-COV-2 and cytomegalovirus in the era of COVID-19. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7:001652. doi: 10.12890/2020_001652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss P. “The ancient and the new”: Is there an interaction between cytomegalovirus and SARS-CoV-2 infection? Immun Ageing. 2020;17:14. doi: 10.1186/s12979-020-00185-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basic-Jukic N. Can hyperimmune anti-CMV globulin substitute for convalescent plasma for treatment of COVID-19? Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:109903. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyce H. Special varieties of esophagitis. In: Sivak M, editor. Gastroenterologic Endoscopy. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders Company; 2000. pp. 601–2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salehi M, Ahmadikia K, Mahmoudi S, Kalantari S, Jamalimoghadamsiahkali S, Izadi A, et al. Oropharyngeal candidiasis in hospitalised COVID-19 patients from Iran: Species identification and antifungal susceptibility pattern. Mycoses. 2020;63:771–8. doi: 10.1111/myc.13137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]