Abstract

Objective:

To compare the prevalence of cognitive symptoms and their functional impact by age group accounting for depression and number of other health conditions.

Methods:

We analyzed data from the 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a population-based, cross-sectional telephone survey of US adults. Twenty-one US states asked participants (n = 131, 273) about cognitive symptoms (worsening confusion or memory loss in the past year) and their functional impact (interference with activities and need for assistance). We analyzed the association between age, depression history and cognitive symptoms and their functional impact using logistic regression and adjusted for demographic characteristics and other health condition count.

Results:

There was a significant interaction between age and depression (p < 0.0001). In adults reporting depression, the adjusted odds of cognitive symptoms in younger age groups (< 75 years) were comparable or greater to those in the oldest age group (≥ 75 years) with a peak in the middle age (45–54 years) group (OR 1.9 (95% Confidence Interval: 1.4–2.5). In adults without depression, adults < 75 years had a significantly lower adjusted odds of cognitive symptoms compared to the oldest age group with the exception of the middle-aged group where the difference was not statistically significant. Over half of adults under age 65 with depression reported that cognitive symptoms interfered with life activities compared to 35.7% of adults ≥ 65 years.

Conclusions:

Cognitive symptoms are not universally higher in older adults; middle-aged adults are also particularly vulnerable. Given the adverse functional impact associated with cognitive symptoms in younger adults, clinicians should assess cognitive symptoms and their functional impact in adults of all ages and consider treatments that impact both cognition and functional domains.

Keywords: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS); cognitive symptoms, age, depression; comorbid health conditions; functional impact

Introduction

Cognitive symptoms are often considered a hallmark of aging; however, they can also be a symptom of diseases, most notably depression. Depression is the leading cause of disability in the world(World Health Organization, 2017) and is commonly accompanied by comorbid physical health conditions (Egede, 2007; Katon, 2011; Moussavi et al., 2007). Cognitive difficulties, defined as a diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day,” constitute one of the criteria for major depressive disorder(American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These cognitive difficulties can be objective or subjective in nature and this study will use the term cognitive symptoms to refer to subjective cognitive impairment. The co-occurrence of cognitive symptoms and depression is associated with poor social function, impairments in everyday functioning, including limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), as well as increased hospitalizations among aging adults (Egede, 2007; Kim et al., 2016; Xiang and An, 2015). Studies on cognitive symptoms have often focused on older adults with the goal of distinguishing depression-related cognitive impairment, which is potentially treatable from dementia-related cognitive impairment for which there are fewer treatment options (Arve et al., 1999).

However, there is evidence that depression-related cognitive impairment may affect younger adults as well. For example, baseline cognitive deficits in the context of depression in middle-aged and older community-dwelling adults have been found to correlate with unremitting depressive symptoms on follow-up assessments (Mojtabai and Olfson, 2004). Objective cognitive dysfunction has been observed in as much as 50% of depressed patients, and baseline cognitive function among individuals with depression predicts functional outcomes 6 months post-discharge (Gualtieri and Morgan, 2008; Jaeger et al., 2006; McIntyre et al., 2015). Still, most of these studies have been small with limited generalizability. Given the significant link between objective and subjective cognitive impairment and functional deficits, it is important to understand the extent to which younger adults experience cognitive symptoms and whether such symptoms contribute to limitations in everyday functioning. Thus, our objective was to examine the relationship between age and cognitive symptoms and associated function in a large population-based sample and evaluate the interaction with depression and the effect of accounting for number of other health conditions. We hypothesized that the relationship between age and cognitive symptoms would differ in those with a history of depression compared to those without.

Methods

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is a population-based random-digit-dialed telephone survey of non-institutionalized U.S. adults administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in conjunction with state health departments. The BRFSS consists of a core survey administered to all participants in all states and territories and optional survey modules, which are administered in those states that choose to use them. In 2011, 21 states administered the cognitive impairment module: 7 administered the survey to their landline-cell phone sample (Hawaii, Illinois, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia, Wisconsin), 5 States to their entire landline sample (Arkansas, Florida, Iowa, Louisiana, North Carolina), and 9 states to one of their landline samples (California, Michigan, Washington, Maryland, NewYork, Oklahoma, Texas, Nebraska, Utah). The median state weighted cooperation rate (percent of those contacted who participated) was 72.9% (range 52.8%-82.0%) and the median state weighted response rate (percent of the estimated eligible who participated) was 52.9% (range 37.4%-66.0%) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). The BRFSS data are publicly available on the CDC website (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2011a) and research with the publicly available BRFSS data is not human subjects research, thus no Institutional Review Board approval was required.

Measures

In order to compare across age groups, age was categorized into 6 groups (Table 1). Cognitive symptoms were assessed with the question, “During the past 12 months, have you experienced confusion or memory loss that is happening more often or is getting worse?” Depression was assessed by the question, “Has a doctor, nurse, or other health professional EVER told you that you have a depressive disorder (including depression, major depression, dysthymia, or minor depression)?” The questionnaire uses the same question structure to assess for other chronic health conditions (coronary heart disease, heart attack (myocardial infarction), hypertension, stroke, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, non-skin cancer, arthritis, kidney disease, visual impairment, and diabetes) which we used to construct a count of other health conditions. Answers of “don’t know” to health conditions questions were counted as negative. Participants reporting cognitive symptoms were asked how often worsening confusion or memory loss had “interfered with [their] ability to work, volunteer or engage in social activities,” led “a family member or friend to provide any care or assistance”, and caused them to give up “household activities or chores [they] used to do.” These variables were dichotomized into “sometimes, usually, or always” and “rarely or never” to have adequate numbers for each category across age groups. They were also asked if they “had discussed with a health care professional increases” in their cognitive symptoms(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2011b). Demographic variables assessed included sex, race/ethnicity, and education.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and History of Depression and Four or more Other Health Conditions

| Sample | Depression | Four or More Other Health Conditions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| raw n | weighted % | wt. row % | 95% CI | wt. row % | 95% CI | |

| Total Sample | 123452 | 100 | 16.5 | 16.0–17.1 | 8.8 | 8.4–9.1 |

| Age (Years) | ||||||

| 18–29 | 7135 | 20.4 | 13.6 | 12.0–15.3 | 0.7 | 0.3–1.1 |

| 30–44 | 20444 | 27.9 | 15.4 | 14.4–16.4 | 2.1 | 1.7–2.6 |

| 45–54 | 22076 | 19.1 | 20.4 | 19.1–21.7 | 7.5 | 6.7–8.3 |

| 55–64 | 29492 | 15.4 | 21.8 | 20.7–22.9 | 15 | 14.1–16.0 |

| 65–74 | 24212 | 9.4 | 15.6 | 14.6–16.6 | 22 | 21.1–23.5 |

| 75 plus | 20093 | 7.8 | 9.7 | 8.8–10.5 | 27 | 26.4–29.1 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 46324 | 48.9 | 12.4 | 11.7–13.2 | 8.2 | 7.7–8.8 |

| female | 77128 | 51.1 | 20.5 | 19.7–21.2 | 9.3 | 8.9–9.7 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White Non Hispanic | 98995 | 65.1 | 18.4 | 17.8–19.0 | 9.7 | 9.3–10.1 |

| Black Non Hispanic | 12285 | 10.9 | 14.5 | 12.7–16.3 | 10 | 9.3–11.7 |

| Hispanic | 6261 | 17.9 | 12.9 | 11.4–14.4 | 5.3 | 4.5–6.2 |

| Asian/PI | 3609 | 4.5 | 6.3 | 3.6–9.0 | 3.4 | 1.9–5.0 |

| Native Am, Other, Unsure | 2302 | 1.5 | 23.2 | 17.1–29.4 | 12 | 9.3–14.8 |

| Education | ||||||

| less than high school | 11536 | 15.3 | 21.6 | 19.7–23.5 | 13 | 12.7–15.0 |

| high school | 37412 | 28.3 | 16.7 | 15.7–17.8 | 9.4 | 8.7–10.0 |

| some college | 33099 | 31 | 17.6 | 16.6–18.6 | 8.8 | 8.2–9.5 |

| college or more | 41405 | 25.4 | 12 | 11.3–12.7 | 4.9 | 4.5–5.3 |

Abbreviations: weighted, wt.; confidence interval, CI; Pacific Islander, PI; American, Am;

Sample

Of the 131,273 participants who were administered the cognitive symptoms screening question (out of 143,846 total participants), 2566 (1.95%) refused or did not know the answer to this question. Of the remaining participants, 5,255 were missing information in one or more of the following categories: race/ethnicity (n=4463), education (n=218), one or more of the chronic health conditions (n=516) and depression (n=85) leading to a final sample size of 123,452.

Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the complex survey procedures of SAS 9.4 and took into account the complex survey design and survey weights in all analyses. In 2011, the BRFSS started using an iterative proportional fitting technique using age, gender, race/ethnicity educational level, marital status, homeowner status and phone source to adjust survey weights until weighted estimates for each dimension converges to Census estimates(Centers for Disease, Control and Prevention, 2012). All percentages reported in the results represent weighted percentages. Analyses included descriptive statistics and logistic regression. Logistic regression using PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC, was performed primarily to control for potential confounders. Variance estimation was performed using the Taylor series method with design degrees of freedom and the NOMCAR option for missing values. Cognitive symptoms were modeled as an outcome with categorical age, depression and a depression/categorical age interaction term in two separate models; one model contained demographic covariates only and the other also adjusted for other health condition count. Covariates include race/ethnicity, sex and educational status. Health condition count was treated categorically from 0 to five or more conditions as model fit statistics (Akaike information criterion and Schwartz criterion) were lower than models treating it as a continuous variable. For the subset of participants (n = 12, 269) reporting cognitive symptoms, further logistic regression models adjusting for demographics and health condition count were performed on each of the functional outcomes. Confidence intervals (CI) for odds ratios are Wald confidence intervals.

Results

Cognitive Symptoms and Depression History in Relation to Age

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics and prevalence of cognitive symptoms and depression in the sample. The mean age of the sample was 46.6 years (interquartile range: 31.3–58.9) and 51.2% were women. In the overall sample, prevalence of cognitive symptoms was 9.5% (95% CI 9.1%-9.9%) and prevalence of history of depression was 16.5% (95% CI 16.0%-17.1%). The prevalence of depression was highest in the middle age groups and lowest in the oldest group (Table 1). Cognitive symptoms were more common in those reporting a history of depression (25.7% (95% CI 24.1%-27.2%) versus 6.3% (95% CI 6.0%-6.7%). The pattern of cognitive symptoms across age groups was different in the depression group versus the no depression group: in those with depression, the prevalence of cognitive symptoms peaked at middle age; whereas, in those without depression the prevalence of cognitive symptoms increased with age and was highest in the oldest age group. (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cognitive Symptoms and Functional Impact by Age and History of Depression

| Cognitive Symptoms weighted (wt.) % (95% Confidence Interval (CI)); n = 123,452 | ||||||

| Age | 18–29 | 30–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75 plus |

| Depression | 17.4 (12.4–22.5) | 21.2 (18.2–24.2) | 31.1 (27.6–34.6) | 30.2 (27.5–32.9) | 28.8 (25.4–32.2) | 26.6 (22.6–30.7) |

| No Depression | 3.5 (2.7–4.3) | 4.8 (4.0–5.6) | 6.9 (6.1–7.8) | 7.2 (6.4–8.0) | 9.2 (8.3–10.1) | 12.5 (11.5–13.5) |

| Interfere with Life Activities wt. % (95% CI); n = 11,890 | ||||||

| Age | 18–29 | 30–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75 plus |

| Depression | 54.8 (38.7–70.9) | 58.2 (50.1–66.4) | 51.6 (44.5–58.6) | 54.4 (49.0–59.8) | 35.3 (27.8–42.9) | 36.7 (27.1–46.2) |

| No Depression | 25.7 (15.3–36.1) | 23.9 (17.2–30.6) | 26.1 (20.7–31.5) | 23.4 (17.9–28.9) | 11.0 (8.2–13.8) | 17.5 (13.5–21.6) |

| Give up Household Activities wt. % (95% CI); n = 11, 890 | ||||||

| Age | 18–29 | 30–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75 plus |

| Depression | 47.3 (30.7–64.0) | 44.8 (36.5–53.0) | 53.0 (46.1–59.8) | 43.9 (38.4–49.3) | 32.6 (25.2–40.0) | 43.1 (33.5–52.8) |

| No Depression | 24.7 (13.7–35.6) | 18.3 (12.4–24.2) | 26.3 (20.5–32.1) | 20.2 (14.7–25.7) | 14.2 (10.3–18.1) | 20.1 (15.9–24.3) |

| Need Family/ Friend Assist wt. % (95% CI); n = 11,931 | ||||||

| Age | 18–29 | 30–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75 plus |

| Depression | 37.8 (21.6–54.1) | 39.4 (31.4–47.3) | 35.8 (29.3–42.3) | 35.4 (30.0–40.7) | 28.7 (21.1–36.2) | 33.1 (22.9–43.3) |

| No Depression | 13.4 (5.1–21.7) | 11.0 (6.1–15.9) | 16.0 (11.3–20.6) | 14.1 (10.3–17.8) | 8.0 (5.4–10.7) | 16.0 (12.5–19.4) |

| Spoke with Professional wt. % (95% CI); n = 11,878 | ||||||

| Age | 18–29 | 30–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75 plus |

| Depression | 44.5 (27.6–61.3) | 34.1 (26.5–41.6) | 36.7 (30.1–43.3) | 32.1 (26.9–37.3) | 28.5 (22.0–35.0) | 23.0 (16.2–29.8) |

| No Depression | 7.4 (2.2–12.6) | 13.5 (9.2–17.8) | 14.3 (10.3–18.3) | 14.0 (10.2–17.7) | 11.8 (8.5–15.1) | 14.5 (11.2–17.9) |

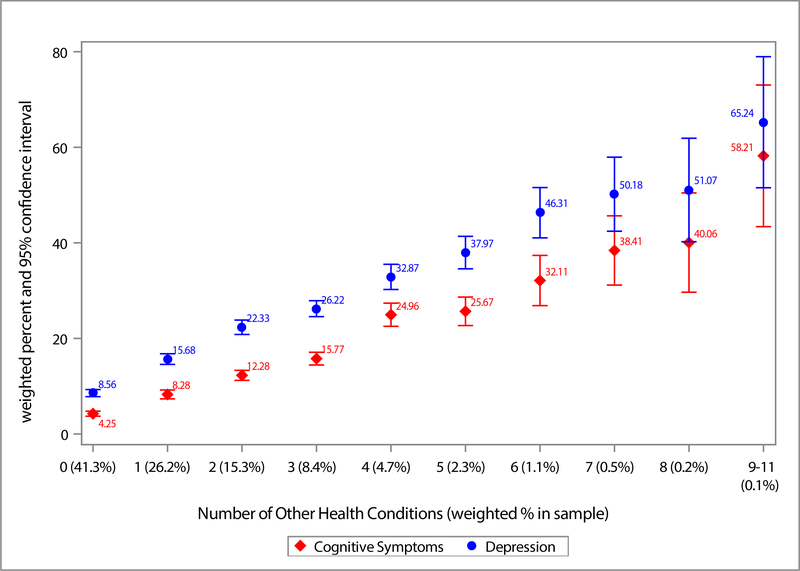

Cognitive Symptoms and Depression History in Relation to Other Health Condition Count

Almost 60% of the sample reported at least one health condition. As the number of reported health conditions increased so did the prevalence of cognitive symptoms and depression (Figure 1). The prevalence of cognitive symptoms was 4.2% (95% CI 3.7%-4.8%) in those with no health conditions and rose to 58.2% (95% CI 43.4%-70.0%) in those with 9 or more health conditions. The prevalence of depression followed a similar pattern, increasing from 8.6% (95% CI 7.8%-9.3%, no health conditions) to 65.2% (95% CI 51.5% -79.9%, 9 or more health conditions).

Figure 1. Cognitive Symptoms and Depression by Other Health Condition Count.

The x-axis shows the number of other health conditions and weighted percentage of participants having that health condition count. The percentage of participants reporting cognitive symptoms (worsening confusion or memory loss in the past 12 months) is shown in red. The percentage of participants reporting a depression history (ever being told by a healthcare provider that they had a depressive disorder) is shown in blue.

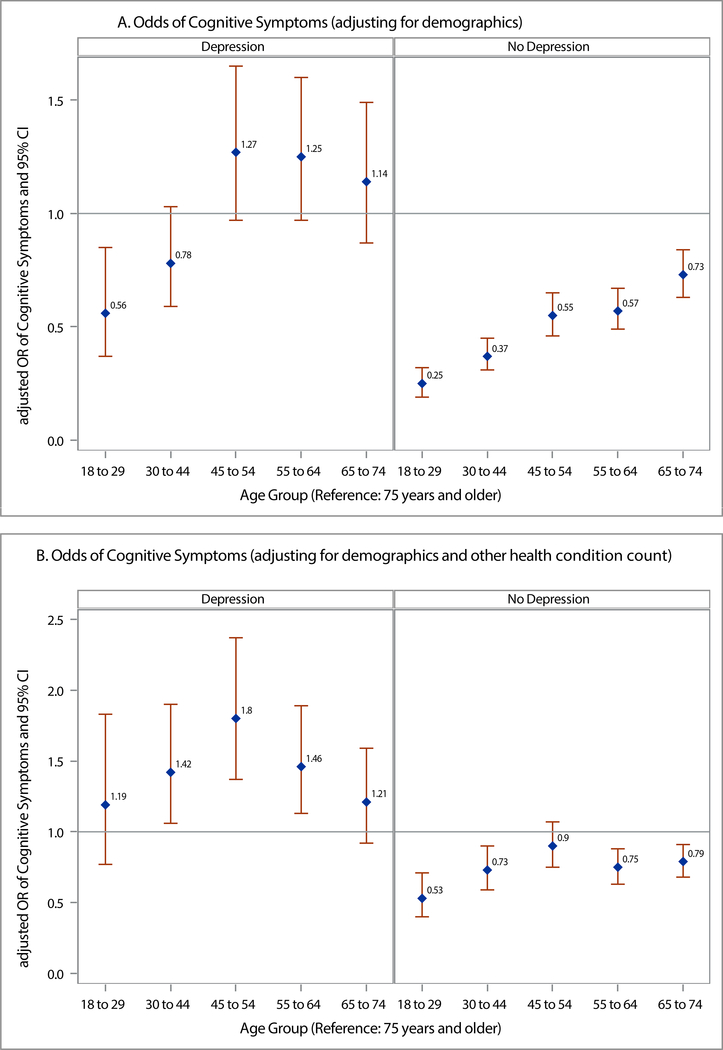

Adjusted Regression Results of Cognitive Symptoms in Relation to Age and Demographics

There was a significant interaction between age and depression in both cognitive symptoms models (demographic adjusted model F (7.77), p < 0.0001; demographic and health count adjusted model F (5.43), p < 0.0001, Type III one-sided F-statistic, numerator degrees of freedom (df) 5, denominator df 138,456 in both models). In the model adjusting for demographics only (Figure 2a), among those reporting depression, the youngest age groups had a lower adjusted odds of cognitive symptoms than the oldest age group, in contrast to the middle age groups where the odds were slightly increased although not statistically different. In those without depression, all the age groups under 75 years had a lower adjusted odds of cognitive symptoms with the youngest age group having the lowest.

Figure 2. Adjusted Odds of Cognitive Symptoms by Age Group and Depression History.

Figure 2a shows the adjusted odds of participants reporting cognitive symptoms (worsening confusion or memory loss in the past 12 months) by age group and depression history using the oldest age group (75 years and older) as the reference and adjusting for demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, education). Figure 2b shows the odds of cognitive symptoms by age group and depression history adjusting for demographics and other health condition count with the oldest age group as the reference. Both models included an age group by depression history interaction term. Abbreviations: OR, odds ration; CI, Confidence interval

After adding number of other health conditions to the model (Figure 2b), in those with depression, none of the younger age groups had a lower odds of cognitive symptoms than the oldest age group and the groups spanning ages 30–64 had a higher adjusted odds of cognitive symptoms with a peak in Journalthe middleage(45–54years) group (OR 1.8(95% CI1.4–2.4)). In those without depression, younger age groups still had a lower adjusted odds of cognitive symptoms, but the difference was not statistically significant in the middle age group (Fig 2b).

In terms of demographic characteristics, while males had a slightly higher odds of cognitive symptoms in the model adjusting only for demographics, this was not significant after adding health condition count to the model. Those with less education than college graduates had a higher odds of reporting cognitive symptoms in both models and the odds increased as the educational attainment decreased (Table S2).

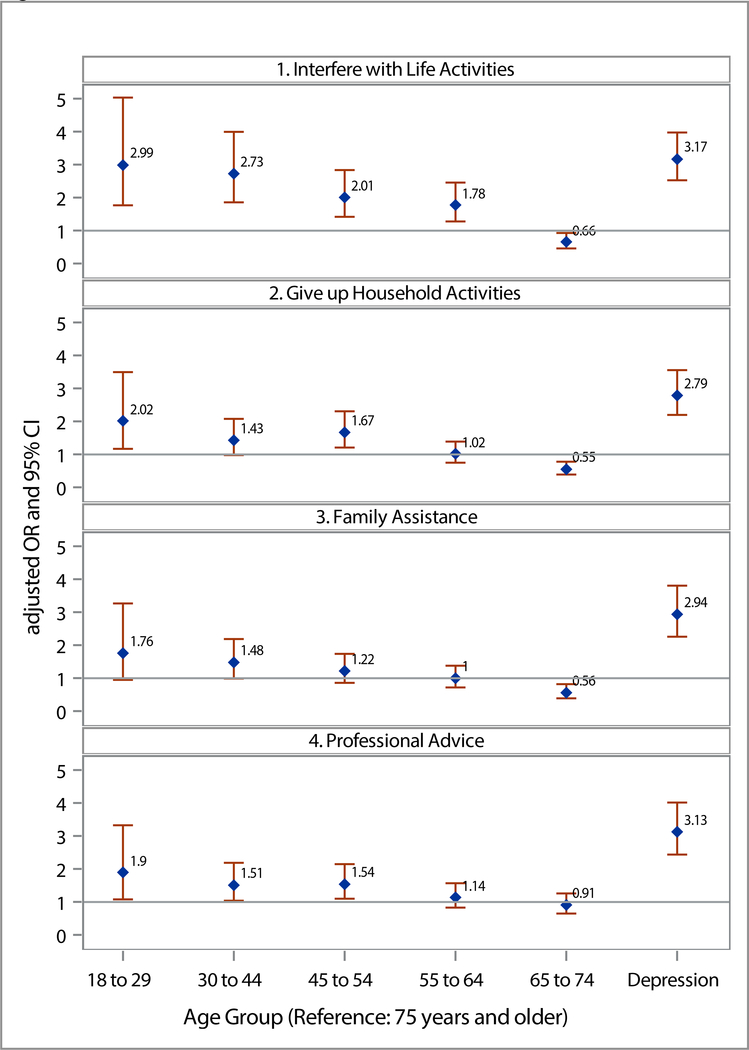

Functional Impact of Cognitive Symptoms

Over half of adults (54.5% (95% CI (50.3%-58.6%) under age 65 with depression reported that cognitive symptoms interfered with work, volunteer or social activities sometimes, usually or always compared to 35.7% (95% CI 29.8%-41.7%) of those 65 years or older. Almost half of adults (47.6% (95% CI 43.4%-51.8%) under age 65 with depression reported that cognitive symptoms had led them to give up household activities compared to 36.0% (95% CI 30.0%-41.0%). There was less of an age difference in those reporting cognitive symptoms requiring assistance from family or friends. Only a minority of participants of all ages sought professional advice for their symptoms. Table 2 gives full details of functional impact by age group and depression status.

In logistic regression evaluating the functional impact of cognitive symptoms and advice seeking, there was not a significant interaction betweens age and depression. Thus, in Figure3 we present simplified models of these outcomes for the whole sample adjusting for demographics and other health condition count. Notably, the odds of any type of functional impact was much higher in those reporting depression, as was the odds of help seeking. The most striking effect of age involved the reporting of interference with life activities which was greatest in the youngest age groups (Fig 3). In general, the 65–74 years age group had lower odds of reporting functional impact although this did not always reach statistical significance. Seeking professional advice about cognitive symptoms was also higher in the younger age groups. There were no differences in functional impact or advice seeking across sexes (Table S2). Non-Hispanic Blacks had a higher odds of functional impact than non-Hispanic whites in all categories and Asians/Pacific Islanders had a much lower odds of professional advice seeking than other racial/ethnic groups. Those with less than a high school education also had a higher odds of functional impact in all categories and those with less than a college education had a lower odds of professional advice seeking than those with a college degree (Table S2).

Figure 3. Adjusted Odds of Functional Impact and Professional Advice Seeking due to Cognitive Symptoms by Age group.

Figure 3 shows the adjusted odds of reporting a functional impact of cognitive symptoms by age group (reference is oldest age group (75 plus years)) and depression history (reference is no history of depression). Each impact was modeled separately and adjusted for demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, education) and number of other health conditions. Abbreviations: OR, odds ration; CI, Confidence interval

Discussion

Our major finding is that for participants with a history of depression, accounting for a number of health conditions and demographic characteristics, cognitive symptoms were not higher in the oldest age groups, rather they peaked in middle age. In contrast, adults without depression followed an expected pattern of lower odds of cognitive symptoms in younger age groups with the exception of the middle-aged (45–54 year old) group where the difference was not statistically significant. Functional impairment from cognitive symptoms was more common in those under 65 with over 50% of those with depression and over 25% of those without depression reporting that these symptoms interfere with life activities. Taken together, our findings suggest that cognitive symptoms in adults with a depression history, after adjusting for the number of other health conditions, occur at a comparable level in younger and older adults. This finding was not seen in adults that did not report depression.

Findings regarding the relationship among subjective complaints, cognition and depression are mixed. In an excellent review of subject cognitive complaints, the extant epidemiological data indicates that subjective cognitive complaints confer an increased risk for mild cognitive impairment and dementia (Jessen et al., 2020). However, Topiwala et al. most recently found subjective complaints were not associated with neurodegeneration but instead reflected depressive symptoms (Topiwala et al., 2021). Brailean et al. found subjective memory complaints predicted objective cognitive decline on a variety of cognitive measures, independent of depressive symptoms, but also found that depressive symptoms amplified subjective cognitive symptoms (Brailean et al., 2019). Together these findings suggest that cognitive symptoms may be independently associated with neurodegeneration and depression, Since such studies typically examine older cohorts, some have concluded that the relationship between depression and cognitive dysfunction is more frequently present in older adults than in younger adults (Drag and Bieliauskas, 2010). The results of our large population-based study suggest that in adults reporting a history of depression, after accounting for medical comorbidities, younger and middle age adults have equivalent or higher reports of cognitive symptoms than older adults. The adjustment for health conditions greatly impacted the adjusted odds ratios of cognitive symptoms, particularly for the youngest age groups with depression, but also attenuated the difference in those without depression. This suggests that some of the increased prevalence of cognitive symptoms in older adults may be due to the effect of multiple health conditions and not age alone. In addition to evaluating the cognitive effects of depression, it is important to evaluate the cognitive effects of comorbid health conditions and where present, the cognitive effects of polypharmacy which is likely more common in those with multiple health conditions.

We found greater functional impact in working age persons with cognitive symptoms which may reflect the increased demands of work compared to retirement. The timing of data collection during a period of economic downturn in the US, might help explain the finding of increased vulnerability of middle age adults and is consistent with other studies showing the greater impact of life events on the risk of MDD in this age group (Stegenga et al., 2012). Our finding is also consistent with other studies showing increased risk of morbidity and mortality including suicide in the 45–54 year old age group (Case and Deaton, 2015). A greater proportion of the oldest age group reported cognitive symptoms than reported depression in our sample which may be consistent with a continued problem of relative under-diagnosis (or underreporting) of depression compared to cognitive problems in this age group, but could also be consistent with the underlying prevalence of both conditions in this age group.

There are some limitations to the current study. First, the survey only asked about lifetime depression, not current depression, and there is no information on severity or duration of depression. On the other hand, there is evidence that there are residual cognitive impairments even in persons with remitted depression (Rock et al., 2013). Future research should address whether residual cognitive deficits in the context of remitted depression are related to recovery or persistent functional deficits in daily life. The same limitation applies to the other chronic health conditions surveyed which if anything would contribute to an underestimation of any potential effect of comorbidities on current cognition.

Second, no objective assessment of cognition is available. The literature on the degree of correlation between subjective and objective memory complaints is mixed (Crumley et al., 2014) and has mainly focused on older adults. As a result, the literature may underestimate the extent of subjective cognitive impairment in depressed young adults. Thus, while our study is consistent with other studies, which showed a strong association between depression and cognitive complaints (Zlatar et al., 2014), weare not able to assess the degree to which these complaints are correlated with objective measures of cognitive functioning. Similarly, the attribution of functional difficulties to cognitive symptoms is based on self-report data and not objective assessments. Although participants were asked whether these difficulties were due to the cognitive symptoms, we cannot exclude the possibility that these difficulties had other causes.

Conclusions

Cognitive symptoms in younger patients with a history of depression are common, affecting 25% of those under age 65. The symptoms also have a significant functional impact on work, volunteer and social activities in over 50% of younger participants with depression and cognitive symptoms. Thus, while efforts to distinguish depression from cognitive symptoms and impairment in older adults remain important, practitioners need to be aware that younger individuals with depression also experience cognitive symptoms which have substantial functional consequences and consider therapies that impact both cognition and function. The middle age group had the highest odds of cognitive symptoms consistent with findings in other studies. These population-based data support the existing literature describing depression-related cognitive symptoms in younger adults, providing additional warrant for further research into depression-related cognitive symptoms and its effect on function in this population.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1: Full Regression Results for Odds of Cognitive Symptoms

Supplemental Table 2: Full Regression Results for Functional Impact Outcomes

Funding Sources

Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Programs in Spinal Cord Injury Medicine (SMS-FR) and Mental Illness Research and Treatment (NCH). National Institutes of Health Career Development Award K08 ES028825 (SMS-FR). Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the Federal Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Bott discloses a commercial interest in Neurotrack. Dr. Gould received research support from Meru Health, Inc, for an investigator-initiated trial. All other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Arve S, Tilvis RS, Lehtonen A, Valvanne J, Sairanen S, 1999. Coexistence of lowered mood and cognitive impairment of elderly people in five birth cohorts. Aging 11, 90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailean A, Steptoe A, Batty GD, Zaninotto P, Llewellyn DJ, 2019. Are subjective memory complaints indicative of objective cognitive decline or depressive symptoms? Findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J. Psychiatr. Res. 110, 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A, 2015. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112, 15078–15083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2011 Summary Data Quality Report [WWW Document]. URL http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2011/pdf/2011_summary_data_quality_report.pdf (accessed 8.3.15).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2011a. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data [WWW Document]. URL https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_2011.htm (accessed 5.10.20).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2011b. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire.

- Centers for Disease, Control, Prevention, 2012. Methodologic changes in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 2011 and potential effects on prevalence estimates. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 61, 410–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crumley JJ, Stetler CA, Horhota M, 2014. Examining the relationship between subjective and objective memory performance in older adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging 29, 250–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drag LL, Bieliauskas LA, 2010. Contemporary review 2009: cognitive aging. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 23, 75–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egede LE, 2007. Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 29, 409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualtieri CT, Morgan DW, 2008. The frequency of cognitive impairment in patients with anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder: an unaccounted source of variance in clinical trials. J. Clin. Psychiatry 69, 1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S, 2006. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 145, 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F, Amariglio RE, Buckley RF, van der Flier WM, Han Y, Molinuevo JL, Rabin L, Rentz DM, Rodriguez-Gomez O, Saykin AJ, Sikkes SAM, Smart CM, Wolfsgruber S, Wagner M, 2020. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 19, 271–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon WJ, 2011. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 13, 7–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Chalem Y, di Nicola S, Hong JP, Won SH, Milea D, 2016. A cross-sectional study of functional disabilities and perceived cognitive dysfunction in patients with major depressive disorder in South Korea: The PERFORM-K study. Psychiatry Res. 239, 353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Xiao HX, Syeda K, Vinberg M, Carvalho AF, Mansur RB, Maruschak N, Cha DS, 2015. The prevalence, measurement, and treatment of the cognitive dimension/domain in major depressive disorder. CNS Drugs 29, 577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, 2004. Cognitive deficits and the course of major depression in a cohort of middle-aged and older community-dwelling adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 52, 1060–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B, 2007. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet 370, 851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock PL, Roiser JP, Riedel WJ, Blackwell AD, 2013. Cognitive impairment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegenga BT, Nazareth I, Grobbee DE, Torres-González F, Svab I, Maaroos H-I, Xavier M, Saldivia S, Bottomley C, King M, Geerlings MI, 2012. Recent life events pose greatest risk for onset of major depressive disorder during mid-life. J. Affect. Disord. 136, 505–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topiwala A, Suri S, Allan C, Zsoldos E, Filippini N, Sexton CE, Mahmood A, Singh-Manoux A, Mackay CE, Kivimäki M, Ebmeier KP, 2021. Subjective Cognitive Complaints Given in Questionnaire: Relationship With Brain Structure, Cognitive Performance and Self-Reported Depressive Symptoms in a 25-Year Retrospective Cohort Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2017. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang X, An R, 2015. The Impact of Cognitive Impairment and Comorbid Depression on Disability, Health Care Utilization, and Costs. Psychiatr. Serv. 66, 1245–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlatar ZZ, Moore RC, Palmer BW, Thompson WK, Jeste DV, 2014. Cognitive complaints correlate with depression rather than concurrent objective cognitive impairment in the successful aging evaluation baseline sample. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 27, 181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1: Full Regression Results for Odds of Cognitive Symptoms

Supplemental Table 2: Full Regression Results for Functional Impact Outcomes