SARS-CoV-2 is a betacoronavirus that uses the angiotensin-converting-enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) receptor to gain entry to cells. This receptor is widely expressed in cardiopulmonary tissues and in monocytes and macrophages [1]. SARS-CoV-2 also encodes proteins that antagonize the interferon (IFN) response to viral infection [2]. Interestingly, the ACE2 receptor is also expressed in human natural killer (NK) cells [1].

NK cells are best known for killing virally infected cells and also mediate antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity [3]. Additionally, IFN-ɣ produced by NK cells induces macrophage activation, T cell Th1 response [3], and may protect the lung from fibrosis by inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and collagen expression [4]. However, scarce information about NK cell counts exists in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.

In order to clarify the role of NK cells in COVID-19, we are conducting a study in 50 patients consecutively admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 confirmed infection, defined as radiological diagnosis of pneumonia and confirmed RT-PCR SARS-CoV-2 infection. All patients gave their oral consent to use anonymized data, following the local pandemic research ethics protocols. NK (CD56 +) lymphocyte counts on admission from patients included in the study have already been analyzed by flow cytometry on peripheral blood.

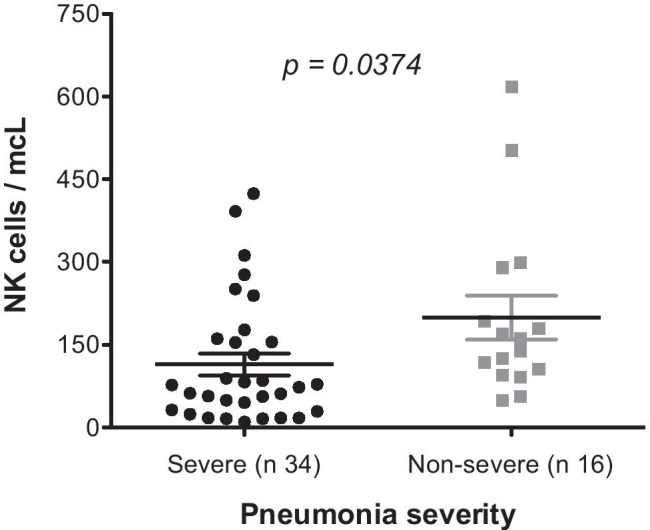

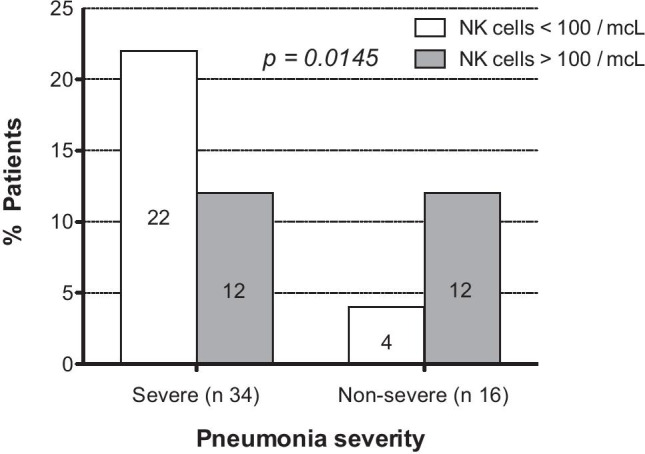

Patients were categorized according to the severity of the pneumonia into non-severe disease and severe disease. Patients were considered to have severe pneumonia based on the presence of any of the following criteria: respiratory frequency ≥ 30/min, oxygen saturation < 90%, and/or CURB65 score ≥ 1. If they did not fulfill these criteria, patients were included in the non-severe group. On admission, 34/50 (68%) patients had severe disease and 16/50 (32%) were diagnosed with non-severe pneumonia. Intriguingly, median NK cells count was 150 cells/mcL (range 49–618) in the non-severe group and 75 cells/mcL (range 10–424) in the severe group, and this turned out to be statistically significant (p = 0.0374) (Fig. 1). Moreover, 12/16 (75%) non-severe patients had NK cells > 100/mcL, whereas 22/34 (65%) severe patients had NK cells < 100/mcL, and this was also statistically significant (p = 0.0145) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

NK cells according to pneumonia severity

Fig. 2.

NK cells > or < 100 according to pneumonia severity pneumonia severity. In the peripheral blood, the normal range of NK cells in adults is 85–505 cells/mcL (4)

NK cells are decreased in peripheral blood of patients admitted to the hospital with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Intriguingly, in our study, NK cells are significantly depleted in patients with severe disease, compared to those with non-severe disease. We hypothesize that interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with NK cells may be important for skewing the fight against SARS-CoV-2 to a potent and protective Th1 (IFN-ɣ) antiviral immune response or an inflammatory (IL-6) and pro-fibrotic (TH2, TGF-β) response, with a subsequently delayed viral clearance and worse clinical picture [4, 5]. Once NK cells, which are major INF-ɣ producers, are defeated by the SARS-CoV-2 viral infection, many infected endothelial cells attract large numbers of activated macrophages and fibroblasts, resulting in the following picture: pro-thrombotic state [1, 6], indiscriminate macrophage activation [7] unable to produce IFN-ɣ, and a pre-fibrotic state induced by interstitial and alveolar lung macrophages incapable of producing IFN-ɣ [4, 8, 9]. Instead, these macrophages produce transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), platelet-derived growth factor (PDFG), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), which activate fibroblasts in response to viral lung damage [4]. Our data suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection may induce a depletion of peripheral blood NK cells and that this characteristic is more pronounced in patients with severe disease.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ricardo Garcia-Muñoz, Email: rgmunoz@riojasalud.es.

Jesus Feliu, Email: jfeliu@riojasalud.es.

Judit Anton-Remirez, Email: jarenero@outlook.es.

Luis Metola, Email: lmetola@riojasalud.es.

Enrique Sosa-Campos, Email: enriquesosacampos@gmail.com.

Maria-Pilar Sanz, Email: mpsanz@riojasalud.es.

Giovanna Farfan, Email: gfarfan@riojasalud.es.

Eztizen Labrador-Sanchez, Email: elabrador@riojasalud.es.

Valvanera Ibarra, Email: vibarra@riojasalud.es.

Jose-Luis Peña, Email: jlpena@riojasalud.es.

Ana Pascual, Email: apascual@riojasalud.es.

María-Jesús Hermosa, Email: mjhermosa@riojasalud.es.

Miriam Blasco, Email: mblasco@riojasalud.es.

Lorena Llerena-Garcia, Email: lllerena@riojasalud.es.

María-José Najera, Email: mjnajera@riojasalud.es.

José Antonio Oteo, Email: jaoteo@riojasalud.es.

References

- 1.Li MY, Li L, Zhang Y, Wang XS (2020) Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infect Dis Poverty. 28;9(1):45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Totura AL, Baric RS. SARS coronavirus pathogenesis: host innate immune responses and viral antagonism of interferon. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2(3):264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, et al. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(5):503–510. doi: 10.1038/ni1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rich RR, Fleisher TA, Shearer WT et al (eds) (2019) Clinical immunology. Principles and practice. 4th edn. Elsevier Saunders 860–873, 716–727

- 5.Tay MZ, Poh CM, Rénia L, et al. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):363–374. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S et al (2020) Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med 382(20):e60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M et al (2020) HLH across speciality collaboration, UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 28;395(10229):1033–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58(5):377–382. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.5.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jose RJ, Manuel A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):e46–e47. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]