Abstract

During leaf senescence, the final stage of leaf development, nutrients are recycled from leaves to other organs, and therefore proper control of senescence is thus critical for plant fitness. Although substantial progress has been achieved in understanding leaf senescence in annual plants, the molecular factors that control leaf senescence in perennial woody plants are largely unknown. Using RNA sequencing, we obtained a high-resolution temporal profile of gene expression during autumn leaf senescence in poplar (Populus tomentosa). Identification of hub transcription factors (TFs) by co-expression network analysis of genes revealed that senescence-associated NAC family TFs (Sen-NAC TFs) regulate autumn leaf senescence. Age-dependent alternative splicing (AS) caused an intron retention (IR) event in the pre-mRNA encoding PtRD26, a NAC-TF. This produced a truncated protein PtRD26IR, which functions as a dominant-negative regulator of senescence by interacting with multiple hub Sen-NAC TFs, thereby repressing their DNA-binding activities. Functional analysis of senescence-associated splicing factors identified two U2 auxiliary factors that are involved in AS of PtRD26IR. Correspondingly, silencing of these factors decreased PtRD26IR transcript abundance and induced early senescence. We propose that an age-dependent increase of IR splice variants derived from Sen-NAC TFs is a regulatory program to fine tune the molecular mechanisms that regulate leaf senescence in trees.

An alternative splicing variant of NAC transcription factor PtRD26 is senescence-associated and regulates leaf senescence by repressing the DNA-binding activities of several NAC transcription factors.

Introduction

Plant senescence occurs at multiple levels, most visibly at the organ and organismal levels, as shown by the splendid changes in leaf color that occur during the autumn season in temperate climates (Keskitalo et al., 2005; Woo et al., 2019). Leaf senescence is the last stage of leaf development and is characterized by the transition from nutrient assimilation into leaves to remobilization to sink tissues (Avila-Ospina et al., 2014). In annual plants, the nutrients released are transferred not only to actively growing young leaves but also to developing fruits and seeds, leading to increased reproductive success (Lim et al., 2007). In perennial plants such as deciduous trees, nutrients are relocated from leaves to form bark storage proteins (BSP) in phloem tissues. They are stored in this form over the winter and then remobilized and reutilized for spring shoot growth (Cooke and Weih, 2005; Keskitalo et al., 2005). Thus, appropriate onset and progression of leaf senescence are critical for plant fitness. Efficient senescence is essential for maximizing viability in the next season or generation, and premature senescence caused by various environmental stresses impairs the yield and quality of crop plants (Breeze et al., 2011).

Leaf senescence is a programmed cell death process and is primarily controlled by developmental age. However, numerous internal and external environmental signals, such as nutrient or plant hormonal signals, osmotic stress, temperature change, and light regimes, are integrated with age information to regulate leaf senescence (Lim et al., 2007; Woo et al., 2019). All major plant hormones have been reported to influence leaf senescence. Ethylene, salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), abscisic acid (ABA), and brassinosteroids (BR) act as inducers of leaf senescence, whereas cytokinins, auxin, and gibberellic acid (GA) act as inhibitors (Gan and Amasino, 1997). Substantial progress has been made in describing leaf senescence at the molecular level through the characterization of hundreds of senescence-related mutants and identification of thousands of senescence-associated genes (SAGs) by means of various omics technologies in annual plants (Kim et al., 2016). These methods have been used to identify numerous factors that regulate leaf senescence, including transcriptional and translational regulators, receptors and components of plant hormone signal pathways, and regulators of metabolism (Woo et al., 2019).

Transcriptome analyses in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) revealed hundreds of transcription factors (TFs) that are involved in regulation of senescence, suggesting that senescence is under the control of a very complex gene regulatory network (GRN; Woo et al., 2019). Members of both the NAC TF family (NAM/ATAF/CUC = NO APICAL MERISTEM/ARABIDOPSIS TRANSCRIPTION ACTIVATION FACTOR/CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDONS) and the WRKY TF families are central factors that modulate transcriptional changes during leaf senescence (Balazadeh et al., 2008). NAC TFs comprise one of the largest families of plant-specific TFs, and the NAC family contains more than 100 genes. Transcriptomic and genetic studies have identified a number of NAC family TFs that are involved in the leaf senescence process. For example, ORESARA1 (ORE1, oresara means “long living” in Korean), sometimes known as ANAC092, is a component of the trifurcate feed-forward loop that involves not only ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 2 (EIN2), a core member of the ethylene signaling pathway, but also miR164 (Kim et al., 2009). Senescence-associated NAC TFs (Sen-NAC TFs), including AtNAP/ANAC029, ANAC019, ANAC047, ANAC055, and ORS1/ANAC059 function downstream of EIN2 (Kim et al., 2014).

In addition, ORE1 and AtNAP, which are direct targets of ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 3 (EIN3), a master TF in ethylene signaling (Li et al., 2013), help to control leaf senescence through regulation of their common target genes ANAC041/079 and VNI2 (Kim et al., 2014). RESPONSIVE TO DESICCATION 26 (RD26)/ANAC072, a stress-related NAC TF, accelerates leaf senescence in the dark by directly activating CHLOROPLAST VESICULATION (CV), thus participating in chloroplast protein degradation (Kamranfar et al., 2018).

Recently, a time-evolving network analysis of 49 Sen-NAC TFs revealed that ANAC017, ANAC082, and ANAC090, referred to as a NAC troika, function as negative regulators of leaf senescence predominantly by regulating levels of SA and reactive oxygen species (ROS; Kim et al., 2018). In rice, OsORE1 and OsNAP regulate leaf senescence induced by plant hormones or stresses through modulation of SAGs transcription (Liang et al., 2014; Mao et al., 2017). The WRKY TF family comprises over 70 members, which are involved in regulating multiple physiological processes (Eulgem et al., 2000). Several WRKY TFs, including WRKY6, WRKY22, WRKY53, WRKY54, WRKY57, WRKY70, and WRKY75, play either positive or negative roles in regulating Arabidopsis leaf senescence (Miao et al., 2004; Miao and Zentgraf, 2007; Ay et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2017).

As a natural phenomenon in temperate deciduous trees, leaf senescence in the autumn attracts wide public attention every year (Keskitalo et al., 2005). The change in leaf color from green to yellow and/or red signals preparation for leaf shedding prior to the upcoming winter (Keskitalo et al., 2005), and the timing of autumn leaf senescence strongly impacts the productivity and nutrient cycle of deciduous forests (Fridley, 2012). Because their life cycles span multiple years, much more age-related information can be obtained from woody perennial plants than from annual plants (Wang et al., 2019). In addition, perennial plants are usually studied in their natural conditions and provide information that cannot be offered by model plants grown in the laboratory (Andersson et al., 2004). Substantial research has been performed with the goal of dissecting the molecular regulatory mechanisms of leaf senescence in woody perennial plants (Andersson et al., 2004; Keskitalo et al., 2005; Fu et al., 2014).

One of the most powerful tools for leaf senescence research is analysis of mutants (Nam, 1997). Unfortunately, classical genetic screens of mutants with altered senescence phenotype are extremely difficult to perform in trees because of their size, relatively slow growth, and long generation times. Thus, the study of perennial leaf senescence is mainly advanced through physiological and transcriptomic strategies (Andersson et al., 2004). Transcriptional analysis of expressed sequence tag (EST) libraries from aspen (Populus tremula) revealed that metallothionein, cysteine proteases, and early light-inducible proteins are most abundant in senescent leaves (Bhalerao et al., 2003). Gene expression analysis provided evidence that energy generation shifts from photosynthesis to mitochondrial respiration due to continuous chlorophyll degradation (Andersson et al., 2004). Previous physiological studies found that a shortened daily photoperiod and lower temperatures can accelerate leaf senescence (Fracheboud et al., 2009). Moreover, across high- and low-latitude sites in the Northern Hemisphere, the process of leaf senescence shows distinct sensitivity to photoperiod and temperature. Trees in high-latitude areas (50° to 70° N) exhibit greater sensitivity to shortened photoperiods, whereas those in low-latitude regions (25° to 49° N) are more sensitive to decreasing temperature (Gill et al., 2015).

The development of RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) methodologies has enabled profiling of the transcriptome in a highly dynamic range of expression levels (Wang et al., 2009). Moreover, the RNA-Seq method does not require prior knowledge of gene models and can be used to effectively identify all transcribed loci in a sample. Powerful tools for analyzing expression data, such as co-expression networks (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008), can be used to identify central genes (hub genes) that have important functions.

Here, we employed high-resolution temporal profiling of transcripts during the autumnal leaf senescence process using three field-grown poplar trees (Populus tomentosa). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of differential gene expression profiles identified 3,459 autumn senescence-associated genes (ASAGs). Our co-expression network analysis of Sen-TFs showed that NAC TFs play critical roles in regulating autumn leaf senescence. Interestingly, a naturally occurring alternative splicing variant (intron retention, IR) of PtRD26, PtRD26IR, was identified and shown to be a repressor of leaf senescence via its dominant-negative effect on PtRD26 and other hub Sen-NAC TFs. Our findings demonstrate that AS events of Sen-TFs provide an additional layer of posttranscriptional/posttranslational regulation to fine-tune the appropriate initiation and progression of leaf senescence.

Results

High-resolution temporal profiling of transcripts associated with autumn leaf senescence in poplar

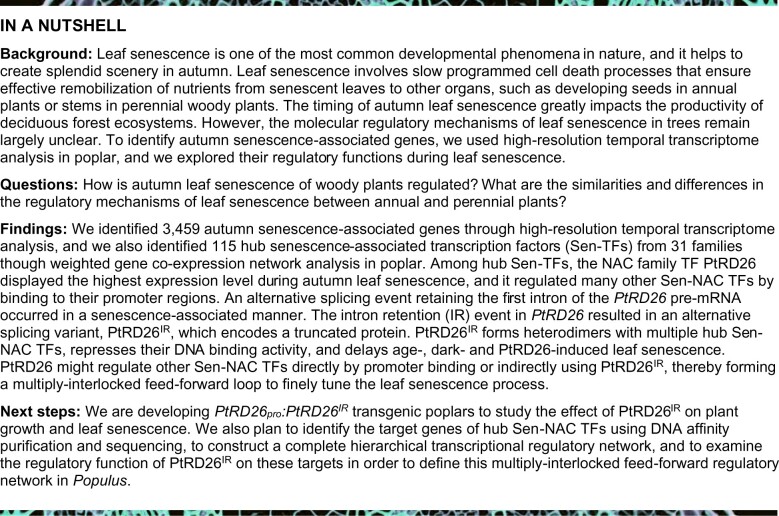

Most previous molecular studies of leaf senescence have focused on annual plants such as Arabidopsis, whereas the molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying leaf senescence in perennial woody plants remain largely unexplored (Andersson et al., 2004). As a first step toward a more detailed picture of autumn leaf senescence regulation, we used RNA-Seq methodology to obtain a high-resolution time course profile of gene expression during the transition from maturity to senescence in P. tomentosa, which was used to identify regulators of leaf senescence. In total, 48 samples were collected from three field-grown trees (Tree A, Tree B and Tree C) at 16 time points (from September 22 to November 17 of 2018) and used for RNA sequencing (Figure 1A). The most visible sign of autumn leaf senescence was a change in leaf color caused by chlorophyll degradation, which led to a gradual reduction in chlorophyll content as leaves aged (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

High-resolution temporal profiling of transcripts associated with autumn leaf senescence in poplar. (A) Autumn leaf senescence in field-grown poplar trees. The images were taken during the sampling period from September 22 to November 17, 2018 (16 time points). Branches and leaves were taken from three individual trees. Representative leaves (L) are shown (L1 to L16). Bar = 10 cm. (B) Chlorophyll contents decline as leaves age. 50 leaves detached from five branches for each replicate tree at one time point were used for measuring chlorophyll contents with a SPAD Chlorophyll Meter. The bars indicate mean ± SD (n = 50). (C) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the poplar leaf transcriptome during autumn senescence. Each data point marked by different color refers to one time point of sampling from three trees (A, B, and C) and represents the gene expression from the RNA-Seq data. Based on PCoA, three major sample clusters were identified: M, mature stage; ES, early senescence stage; LS, late senescence stage. (D) Hierarchical clustering of the expression profiles of 14,776 differentially expressed genes (DEGs). (E) Hierarchical clustering showing expression changes in DEGs that were categorized into eight clusters (C1–C8). Auto-scaled log2(FPKM) values of transcripts in each cluster are shown. The numbers of genes/transcription factors are labeled. C, cluster. (F) MapMan functional categories enriched in differential co-expression modules (C1–C8). (G) Expression patterns of representative genes in each cluster are shown.

To identify dynamic changes occurring in the transcriptome during leaf senescence, we performed principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) to order samples according to their global similarity/dissimilarity (Gower, 1967). The ordination plot showed that the global patterns of the transcriptomes varied markedly over time, as indicated by the first principal component axis, which explained 69.6% of the total variation (Figure 1C). The second principal component axis, which explained the variation between the in vivo transcriptomes, covered only 5.4% of the total variation (Figure 1C). Based on the PCoA analysis, it was evident that dynamic transcriptome changes were primarily caused by changes in developmental stages (Figure 1C). To provide an overview of the expression data, we performed an unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis of 14,776 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in all samples, and this analysis identified three major sample clusters: mature (M), early senescence (ES), and late senescence (LS; Figure 1D).

To provide further insight into functional transitions that occur with autumn leaf senescence, we clustered the DEGs into eight clusters (denoted C1 to C8) using hierarchical clustering with default parameters (Figure 1E). The transcript levels of genes in C1, C2, and C3 (3,459) increased during leaf senescence and were defined as autumn senescence-associated genes (ASAGs; Figure 1E and Supplemental Data Set 1). In contrast, the expression levels of genes in C6 and C8 decreased as leaves aged, and these were defined as senescence-downregulated genes (SDGs). A comparison between the set of identified ASAGs (3,459) and Arabidopsis SAGs (3,852) deposited in the Leaf Senescence Database (https://bigd.big.ac.cn/lsd/; Li et al., 2020) revealed an overlap of 1,029 homologous genes between the two sets (Supplemental Figure 1), indicating that leaf senescence is highly similar in annual versus perennial leaf senescence. We next performed MapMan annotation to assign genes into functional categories for each cluster (Thimm et al., 2004) and found that ASAGs are mainly involved in metabolic pathways, including carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism, and regulate hormone responses (Figure 1, F and G). These functions were further confirmed by KEGG pathway annotation and Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis (Supplemental Figure 2), suggesting that ASAGs participate in degradation pathways and hormonal signaling processes.

Identification of hub TFs using a gene co-expression network analysis

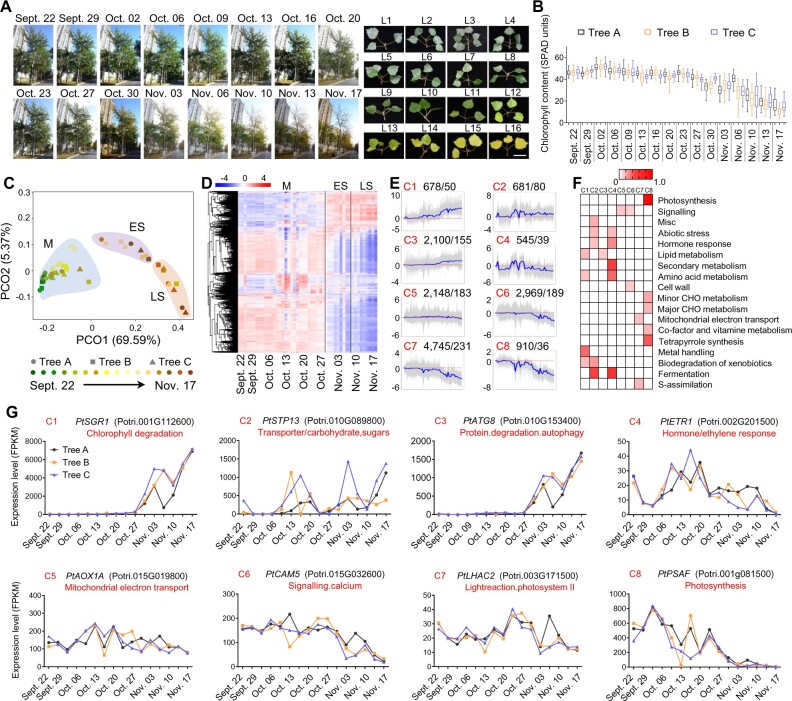

Given that leaf senescence is accompanied by genome-wide changes in gene expression, dynamic activation of TFs is thought to be a key regulatory mechanism regulating the age-dependent expression of thousands of SAGs (Woo et al., 2019). To identify hub TFs, we performed weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) of 285 senescence-associated TFs (Sen-TFs) and 3,174 ASAGs (Figure 1E). In total, 115 Sen-TFs from 31 families were identified as hub Sen-TFs (Figure 2A and Supplemental Data Set 2). Intriguingly, 16 NAC TFs (∼14%) were categorized as hub Sen-TFs (Figure 2A). In comparison with other TF families, NAC-TFs were overrepresented in the group of hub Sen-TFs (Supplemental Figure 3), suggesting that Sen-NAC TFs play a critical role in controlling autumn leaf senescence in poplar.

Figure 2.

Identification of hub Sen-TFs using co-expression network analysis. (A) Co-expression network analysis of ASAGs. The WGCNA package for R software was used to calculate the correlation coefficient with default parameters. Genes with correlation coefficient value > 0.4 were selected for visualization in cytoscape. The hub Sen-TFs are shown with large polygons, while other ASAGs are shown with small red circles. (B) Hierarchical clustering of the expression profiles of 149 NAC TFs to identify Sen-NAC TFs (23 TFs, box). The log2(FPKM) values were employed into Heml v1.0 software for similarity metric (Euclidean distance) and clustering (maximum linkage algorithm) analysis and visualization. (C) Phylogenetic tree of 110 NAC TFs from Arabidopsis and 23 Sen-NAC TFs in poplar in (B). ClustalX2.1 software was used for sequence alignment, and MEGA7 was applied for data visualization with neighbor-joining algorithm. The 23 Sen-NAC TFs were mainly divided into two phylogenetic branches marked as yellow. See Supplemental File 2 for a text file of the alignment used. (D) Identification of hub Sen-NAC TFs during autumn leaf senescence by co-expression network analysis. WGCNA package with default parameters was used for network analysis, and cytoscape was used for visualization. The size of the circle reflects the ranking of genes. 10 hub Sen-NAC TFs are shown in cyan. (E) Venn diagrams showing the overlaps among the identified hub Sen-NAC TFs through three different strategies in (A), (B), and (D).

To provide an overview of the expression patterns of NAC TFs, we carried out an unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis of NAC family TFs (Figure 2B and Supplemental Data Set 3). In total, 23 NAC TFs exhibited a gradual increase in transcript abundance during autumn leaf senescence (Figure 2B), suggesting that these Sen-NAC TFs participate in regulating leaf senescence. To test this possibility, we analyzed the phylogenetic relationships between these 23 Sen-NAC TFs in poplar and 110 NAC family TFs in Arabidopsis, a number of which have been functionally characterized in leaf senescence (Li et al., 2018). Notably, most of the 23 Sen-NAC TFs belong to two subclades based on protein sequence similarity, with 17 aligning to one subclade and 3 aligning with another subclade (Figure 2C). Interestingly, most Sen-NAC TFs in Arabidopsis that are known to promote or delay leaf senescence, including ORE1/ANAC092 and AtNAP/ANAC029, also belong to these two subclades (Li et al., 2018), suggesting that the Sen-NAC TFs identified here might play an important role in poplar leaf senescence.

Next, we performed WGCNA to identify hub genes in NAC family TFs during autumn leaf senescence (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008). We identified 10 hub NAC TFs (Figure 2D), among which 6 TFs were also identified in the previously mentioned WGCNA and unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis: PtNAC013/PtRD26, PtNAC039, PtNAC055, PtNAC076, PtNAC086/PtNAP, and PtNAC109/PtORE1 (Figure 2, A, B, and E). As a result, AtNAC055 and AtNAC076, the orthologs of PtNAC055 and PtNAC076, respectively, have been identified as hub NAC TFs by a time-evolving network analysis of 49 Sen-NAC TFs in Arabidopsis (Kim et al., 2018), further supporting our findings.

PtRD26 directly regulates multiple downstream SAGs that participate in transcriptional regulation and nutrient recycling

To investigate the functions of the identified hub genes in leaf senescence, we first generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing PtRD26 in Col-0 (35Spro:PtRD26/Col-0) and rd26 (35Spro:PtRD26/rd26) mutant backgrounds, partly due to the finding that PtRD26 showed the highest expression level during autumn leaf senescence (Supplemental Data Set 1). Compared to Col-0 and rd26 mutant plants, 35Spro:PtRD26/Col-0 and 35Spro:PtRD26/rd26 plants displayed a precocious leaf senescence phenotype at 38 days (Supplemental Figures 4, A–C). The fourth rosette leaves of the 35Spro:PtRD26/Col-0 and 35Spro:PtRD26/rd26 plants became yellow from the tip, whereas the leaves of Col-0 and rd26 plants retained their green color (Supplemental Figure 4B), suggesting that PtRD26 functions as a positive regulator of leaf senescence. Similarly, the transgenic plants of 35Spro:PtNAC055/Col-0 and 35Spro:PtNAC076/Col-0 displayed an early senescence phenotype in comparison with Col-0 (Supplemental Figures 4, D–F), indicating that these hub Sen-NAC TFs positively regulate leaf senescence.

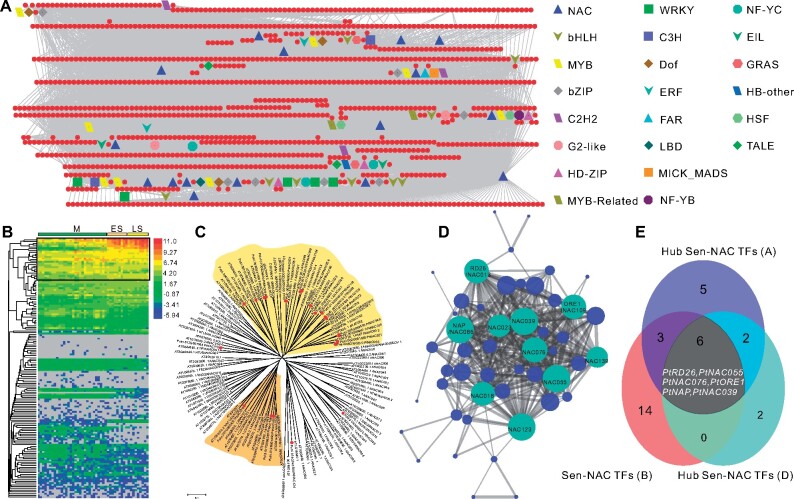

To study the regulatory role of PtRD26 in detail, we screened putative candidate targets of PtRD26 by searching for the binding site sequences of AtRD26 identified in Arabidopsis (Supplemental Figure 5; Kamranfar et al., 2018). Binding activity was further confirmed both by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) coupled with quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) using P. tomentosa protoplasts transiently expressing 35Spro:GFP-PtRD26 and by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). We found that Sen-TFs, PtORE1, PtNAP, and PtEIN3, whose homologs in Arabidopsis are key positive regulators of leaf senescence (Guo and Gan, 2006; Kim et al., 2009; Li et al., 2013), were the targets of PtRD26 (Figure 3, A–C and 3, E–G). Meanwhile, STAY-GREEN 1 (PtSGR1), which is involved in chlorophyll degradation (Figure 3, D and H), CHLOROPLAST VESICULATION (PtCV), which is involved in chloroplast protein degradation (Figure 3, I and M), and lysine-ketoglutarate reductase (PtLKR), which is involved in amino acid (lysine) catabolism (Figure 3, J and N), were also identified as targets of PtRD26, suggesting that PtRD26 is a regulator of metabolic reprogramming/nutrients recycling during autumn leaf senescence.

Figure 3.

ChIP-qPCR and EMSAs of the binding of PtRD26 to the promoters of multiple target genes. (A–D) and (I–L) ChIP-qPCR analysis of PtRD26 binding to the promoters of PtORE1 (A), PtNAP (B), PtEIN3 (C), PtSGR1 (D), PtCV (I), PtLKR (J), PtLOX2 (K), and PtACS6 (L). A monoclonal anti-GFP antibody was used for DNA immunoprecipitation from P. tomentosa protoplasts that transiently expressed 35Spro:GFP-PtRD26. All values of PtACT2 were set as 1 and used as an internal control for enrichment normalization. Biological triplicates were averaged and displayed by P values from two-tailed Student’s t test (Supplemental File 1). The bars indicate mean ± SD (n = 3). P represents the position of the binding site of PtRD26 in the promoter region (see Supplemental Figure 5). (E–H) and (M–P) EMSAs of PtRD26 binding to the promoters of PtORE1 (E), PtNAP (F), PtEIN3 (G), PtSGR1 (H), PtCV (M), PtLKR (N), PtLOX2 (O), and PtACS6 (P). Purified full-length PtRD26 proteins were used for EMSA experiments. The probes were biotin-labeled for the protein-DNA combination, and un-labeled probes were applied as competitors. +, added, ++, added at ten times the amount.

JA and ethylene induce leaf senescence in many plant species (He et al., 2002). Other downstream targets of PtRD26 included lipoxygenase 2 (LOX2), which is required for the biosynthesis of JA, and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase 6 (ACS6), which encodes a rate-limiting enzyme of ethylene production (Figures 3, K–L and 3, O–P), suggesting that PtRD26 also regulates the biosynthesis of senescence-associated plant hormones (Figure 1, F and G). Taken together, the genetic and in vivo ChIP and in vitro EMSA data demonstrate that PtRD26 acts as a hub gene to promote leaf senescence by directly regulating multiple downstream SAGs.

PtRD26IR is a senescence-associated splicing variant of PtRD26 that delays age-, dark- and PtRD26-induced leaf senescence

To further investigate the functions of Sen-NAC TFs in leaf senescence, we either transiently expressed them in the leaves of P. tomentosa and N. benthamiana plants or generated inducible-expressing transgenic plants in Arabidopsis. Total RNA extracted from senescent poplar leaves was used to generate cDNA of Sen-NAC TFs. During the cloning process, we noticed a larger band (∼1.1 kb) in addition to the expected PCR product (∼1 kb) from PtRD26 (Figure 4A). Sequencing of this larger fragment revealed that it was produced through an alternative splicing (AS) event retaining the first intron (Supplemental Figures 6, A–B), which was designated PtRD26IR in this study. Interestingly, this intron-retaining splicing variant of PtRD26 was only detected in the cDNA prepared from senescent leaves but not nonsenescent (mature) leaves (Figure 4A;Supplemental Figure 6C), suggesting that the identified AS event occurs in a senescence-associated manner.

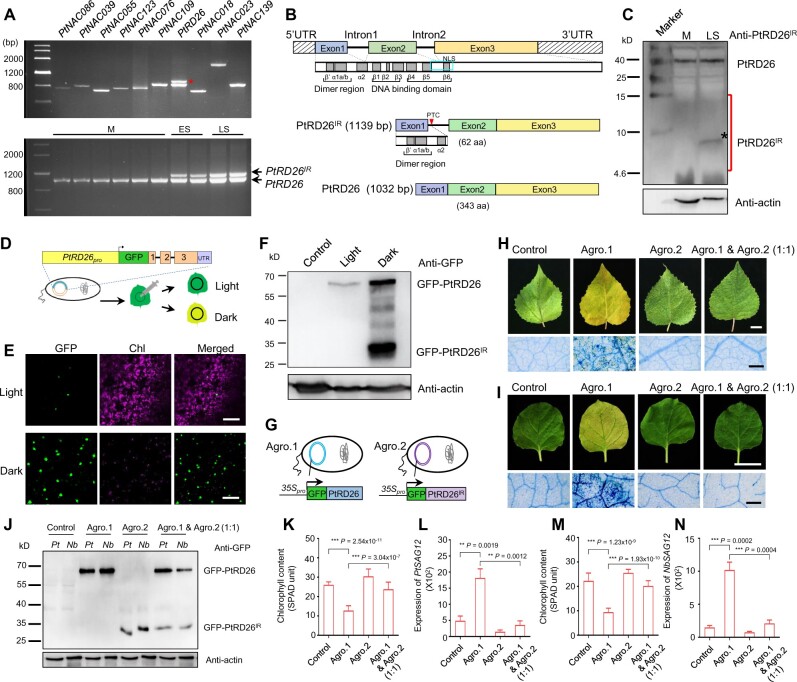

Figure 4.

Identification and functional analysis of alternative splicing variants of PtRD26 during leaf senescence. (A) Identification of alternatively spliced transcripts of PtRD26 in senescent leaves by RT–PCR. 10 hub Sen-NAC TFs identified in Figure 2D were analyzed, and an intron-retaining transcript was observed in PtRD26 (red asterisk) in senescent poplar leaves (top). Senescence-associated alternative transcript of PtRD26 was confirmed by RT–PCR using leaves collected at different developmental stages (bottom). M, mature leaves, ES, early senescent leaves, LS, later senescent leaves. (B) Genomic and protein structures of PtRD26 and the splicing variant PtRD26IR. A blue rectangle indicates the predicted nuclear localization sequence (NLS). A red triangle indicates a premature termination codon (PTC) at intron 1. (C) Immunoblot analysis of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR proteins in mature and later senescent poplar leaves using anti-PtRD26IR antibody. An asterisk indicates the identified PtRD26IR in senescent leaves, and a red line shows the gel region used for mass spectrometry analysis. (D) Schematic diagram of GFP-tagged vector used for analyzing protein accumulation of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR during dark-induced leaf senescence process. (E) Dark treatment promotes protein accumulation of GFP-PtRD26 and GFP-PtRD26IR. The injected tobacco leaves were subjected to darkness treatment and then used for detecting GFP inflorescence via laser scanning confocal microscopy. Chl, chlorophyll autofluorescence. Bar = 100 μm. (F) Immunoblot analysis of GFP-PtRD26 and GFP-PtRD26IR proteins in dark-induced senescent tobacco leaves using an anti-GFP antibody. (G) Schematic diagram of GFP vector construction. (H) PtRD26IR represses PtRD26-induced leaf senescence (top) in poplar. Trypan blue staining of treated leaves showing dead or dying cells as blue-colored patches (bottom). Bars in (H) and (I) = 2 cm (top panels) and 500 μm (bottom panels). (I) PtRD26IR represses PtRD26-induced leaf senescence in tobacco leaves. (J) Immunoblot analysis of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR proteins in P. tomentosa (Pt) and N. benthamiana (Nb) leaves using an anti-GFP antibody. (K) Chlorophyll content of the leaves shown in (H). (L) qRT–PCR analysis of PtSAG12 expression in the leaves shown in (H). (M) Measurement of chlorophyll contents in the leaves shown in (I). (N) qRT–PCR analysis of NbSAG12 expression in the leaves shown in (I). P values in K, L, M, and N are from two-tailed Student’s t test (Supplemental File 1).

We next analyzed the RNA-Seq data to detect all the AS events as leaves aged. Overall, we identified 3,843 genes that were differentially alternatively spliced (DAS; Supplemental Figure 7 and Supplemental Data Set 4). Out of these genes, 2,165 alternative splicing variants were produced at the senescent stage and were defined as senescence-associated alternative splicing variants (Sen-ASVs), suggesting that AS is widely involved in regulating leaf senescence. Expectedly, PtRD26IR was also detected by transcriptome analysis (Supplemental Figure 8). To further investigate the relationship between PtRD26IR and leaf senescence, we measured the expression levels of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR in mature and senescent leaves. As expected, the transcript abundance of PtRD26 increased as leaves aged (Supplemental Figure 9). Intriguingly, the expression levels of PtRD26IR were also upregulated with the progression of leaf senescence (Supplemental Figure 9).

Next, we examined whether the PtRD26IR mRNA was translated into a protein product. The full length PtRD26 transcript was predicted to produce a 343-amino acid (aa) protein, whereas PtRD26IR would encode a 62-aa peptide because of a premature termination codon (PTC) in the retained intron 1 (Figure 4B). As a result, PtRD26IR retained the protein dimerization domain but lacked the DNA binding domain (based on amino acid sequence alignment, Figure 4B;Supplemental Figure 10). Because PtRD26IR mRNA harbors a PTC that is predicted to be degraded by the nonsense mediated mRNA decay (NMD) pathway (Kalyna et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2015), we then examined whether PtRD26IR is subjected to NMD-targeted RNA decay. To this end, we generated a construct with the genomic DNA sequence of PtRD26 including the promoter region, the 5’ untranslated region, exons, introns, and the 3’ untranslated region. This construct was transiently expressed in Arabidopsis wild-type Col-0 and loss-of-function mutant of UP FRAMESHIFT1 (upf1-5), a core component of NMD machinery (Arciga-Reyes et al., 2006; Supplemental Figure 11A). In comparison with three known NMD targets (At5G62760b, AGL88, and At1g66710; Arciga-Reyes et al., 2006), no evident increase in the PtRD26IR mRNA level was observed in upf1-5, and this was confirmed in NbUPF1-silenced tobacco leaves using a virus-induced gene silencing system (VIGS-NbUPF1; Supplemental Figure 11). These data suggest that the PTC of PtRD26IR might not be efficiently targeted by NMD machinery.

To further assure that PtRD26IR might play a functional role, we performed immunoblot analysis to detect the presence of the PtRD26IR-encoded protein. Protein-specific polypeptides (aa 2-13) were selected as immunogens to make monoclonal antibodies specific for either PtRD26 or PtRD26IR (Supplemental Figure 12). Interestingly, we observed that a protein band close to the predicted molecular weight (∼7.5 kD) appeared in the senescent leaves (Figure 4C). To further confirm the existence of PtRD26IR, the PAGE gels containing the proteins (∼15 kD–∼4.6 kD, red line in Figure 4C) extracted from nonsenescent or senescent leaves were subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion, followed by tandem mass spectrometry analysis (Figure 4C). Of the four expected peptides, two were detected in senescent leaves but not in nonsenescent leaves (Supplemental Data Set 5), strongly supporting the presence of PtRD26IR as leaves aged. Also, we detected the production of PtRD26IR in tobacco senescent leaves by transiently expressing an N-terminal GFP fusion plasmid with the PtRD26 genomic DNA sequence, including the promoter region and all introns (Figure 4D). In senescent leaves induced by dark treatment for 7 d, stronger GFP signal and weaker chlorophyll autofluorescence can be detected, indicating that darkness induces accumulation of PtRD26 (Figure 4E). Immunoblot analysis revealed that dark treatment promoted the accumulation of both GFP-PtRD26 and GFP-PtRD26IR (Figure 4F).

To explore the effect of the senescence-associated AS event (Sen-AS) on leaf senescence, we transiently expressed the DNA constructs of 35Spro:GFP-PtRD26 or/and 35Spro:GFP-PtRD2 IR in the leaves of P. tomentosa and N. benthamiana via A. tumefaciens infiltration (Figure 4, G–I). First, we immunoblotted leaf extracts using a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody to detect accumulation of GFP-PtRD26 and GFP-PtRD26IR in these leaves. The expected protein bands (∼65 kD for GFP-PtRD26 versus ∼34 kD for GFP-PtRD26IR) were observed in the protein extracts of transiently overexpressed leaves in P. tomentosa and N. benthamiana but were not seen in the control leaves (Figure 4J), indicating that the transient protein expression system is effective. Second, the transient overexpressing leaves were treated under dark conditions to detect the influence of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR on leaf senescence (Figure 4, H–I). Compared with the control, the P. tomentosa and N. benthamiana leaves overexpressing PtRD26 became yellow, having dead or dying cells and lower chlorophyll content as well as early induction of senescence marker gene PtSAG12 or NbSAG12 upon dark treatment for 10 d. In contrast, leaves overexpressing PtRD26IR remained green, showing both a higher level of chlorophyll content and delayed induction of PtSAG12 or NbSAG12 in comparison with the control plants (Figure 4, K–N). This suggests that PtRD26 promotes but PtRD26IR delays the dark-induced leaf senescence. Third, to further investigate whether PtRD26IR could antagonize the function of PtRD26, we generated the transient overexpressing P. tomentosa and N. benthamiana leaves using the mixture of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR (Figure 4, H–I). Compared with leaves expressing PtRD26 alone, the expression of PtRD26IR led to the delayed senescence phenotypes, including higher levels of chlorophyll content and lower levels of PtSAG12 or NbSAG12 transcripts (Figure 4, K–N). This demonstrates that PtRD26IR effectively represses PtRD26-induced leaf senescence.

Next, we examined the effect of PtRD26IR on PtRD26-induced leaf senescence under normal conditions in Arabidopsis. To this end, an inducible expression system, ER8pro:GFP-PtRD26IR (hygromycin resistance; Zuo et al., 2000), was used to generate the transgenic plants in the Col-0 and PtRD26-overexpressing lines (PtRD26ox, basta resistance). The GFP-PtRD26IR protein (∼34 kD) was clearly detected after treatment with β-estradiol (Supplemental Figure 13A). Moreover, induction of GFP-PtRD26IR delayed leaf senescence in the Col-0 and PtRD26ox backgrounds under normal conditions (Supplemental Figure 13B). This was evidenced by an increased percentage of green leaves and elevated chlorophyll contents, as well as by decreased expression of AtSAG12 (Supplemental Figure 13, C–E). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that the splicing variant PtRD26IR, which accumulates in an age-dependent manner, functions as a negative regulator of age-, dark- and PtRD26-induced leaf senescence.

PtRD26IR represses the function of PtRD26 by disrupting its binding to target genes

Next, we investigated how PtRD26IR impairs the function of PtRD26. Given that transcription factors execute their functions by activating and/or repressing the expression of downstream target genes (Franco-Zorrilla et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2017), we hypothesized that PtRD26IR interferes with binding of PtRD26 to potential targets. To test this possibility, EMSA experiments were performed to assess whether the presence of PtRD26IR disturbs the binding of PtRD26 to the promoters of PtORE1, PtNAP, and PtSGR1 (Figure 5, A–C). Consistent with the aforementioned results (Figure 3), PtRD26 alone could directly bind to the conserved sequence motif in the promoters of PtORE1 (Figure 5A), PtNAP (Figure 5B), and PtSGR1 (Figure 5C). However, when PtRD26IR was expressed in the reaction containing PtRD26, no evident band shift was observed, suggesting that PtRD26IR strongly impairs the binding of PtRD26 to its targets (Figures 5, A–C and Supplemental Figure 14). Consistent with the fact that PtRD26IR lacks the DNA binding domain (Figure 4B), it alone did not bind to the targets of PtRD26 (Figures 5, A–C; Supplemental Figure 14, A–B).

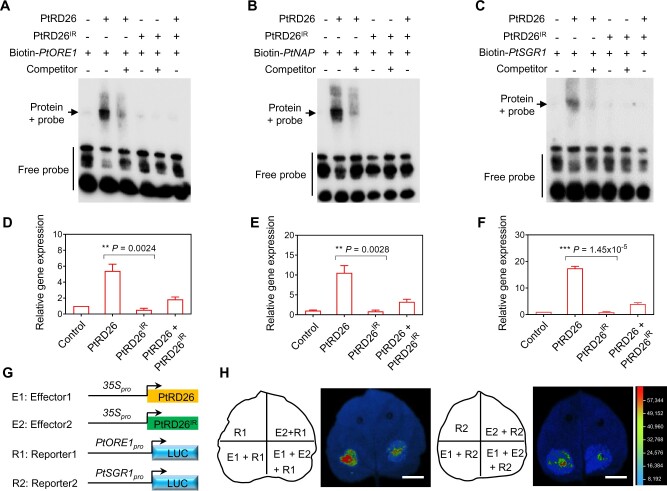

Figure 5.

PtRD26IR represses the activity of PtRD26 by disrupting its binding to downstream targets. (A–C) EMSAs of the inhibitory effects of PtRD26IR on binding of PtRD26 to its downstream targets PtORE1 (A), PtNAP (B), and PtSGR1 (C). The shifted complex is indicated as an arrow on the left. (D–F) qRT–PCR analysis of the expressions of PtORE1 (D), PtNAP (E), and PtSGR1 (F). P. tomentosa protoplasts overexpressing PtRD26, PtRD26IR, or PtRD26 together with PtRD26IR (PtRD26 & PtRD26IR) were used for isolation of total RNA. Protoplasts expressing pUC19-35Spro:GFP were used as the controls that were set as 1. (G) and (H) Analysis of the effects of PtRD26IR on PtRD26 using effector/reporter-based gene transactivation assays in N. benthamiana leaves. The schematic illustrates the effector and reporter structures for PtORE1 (R1) and PtSGR1 (R2) (G). Resuspended E1 and/or E2, infiltration buffer was mixed with an equal volume of R1 or R2 and injected into tobacco leaves. The construct containing only the reporter was used as the control. P values in (D), (E), and (F) are from two-tailed Student’s t test (Supplemental File 1). Bar in (H) = 1 cm.

To verify the inhibitory effect of PtRD26IR on PtRD26, we transiently expressed PtRD26 and PtRD26IR individually or simultaneously in P. tomentosa protoplasts. Expression of PtRD26 alone induced ∼5-fold, 10-fold and 16-fold increases of endogenous PtORE1, PtNAP, and PtSGR1 gene expression, respectively (Figure 5, D–F). Simultaneous expression of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR significantly reduced the magnitude of these changes in expression (Figure 5, D–F), supporting that PtRD26IR represses the activity of PtRD26. Moreover, our gene transactivation assays using an effector/reporter-based method in N. benthamiana leaves confirmed both that PtRD26 activated the expression of PtORE1 and PtSGR1 and that PtRD26IR disrupted this effect (Figure 5, G–H). Together, these results clearly demonstrate that the splicing variant PtRD26IR interferes with the action of PtRD26 by disrupting its binding to the target genes.

PtRD26IR physically interacts with PtRD26 and other related NAC TFs

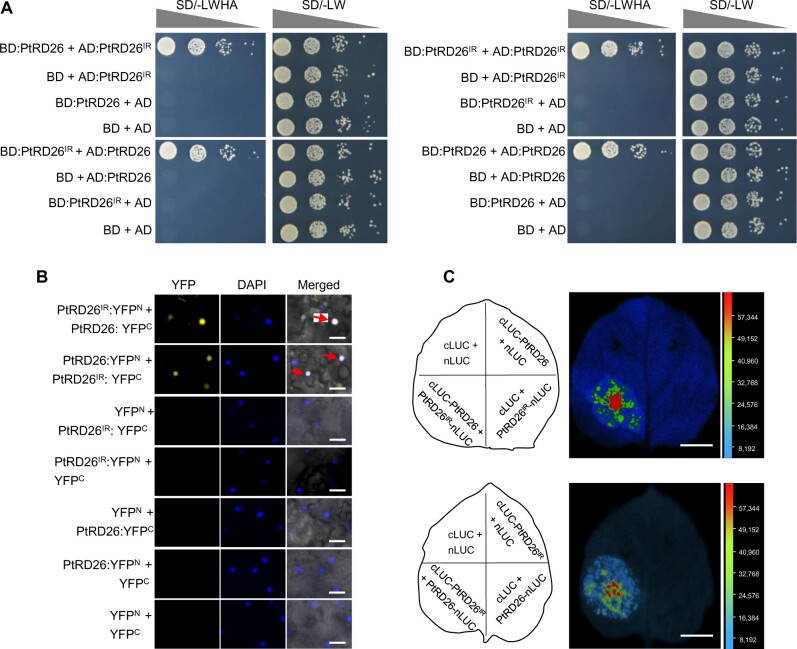

We next explored the mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of PtRD26IR on PtRD26. Given that PtRD26IR retains the dimerization domain but lacks other parts of PtRD26 (Figure 4B), we hypothesized that PtRD26IR would form heterodimers with PtRD26. To test this possibility, we first performed yeast two-hybrid assays to examine potential PtRD26IR-PtRD26 interactions. As expected, PtRD26IR and PtRD26 formed heterodimers in yeast cells (Figure 6, left). PtRD26IR and PtRD26 also formed homodimers with themselves (Figure 6, right). Notably, PtRD26IR can also interact strongly with other hub Sen-NAC TFs, including PtNAC039, PtNAC055, PtNAC076, PtNAC086, and PtNAC099, as well as PtNAC109, and it displayed a weak interaction with PtNAC009, PtNAC110, and PtNAC124 (Supplemental Figure 15). Interestingly, those selected Sen-NAC TFs that interacted with PtRD26IR showed similar expression patterns during leaf aging rather than having similar protein sequences (Supplemental Figure 16). Moreover, PtRD26IR also disturbed the binding of PtNAC055, PtNAC086/PtNAP, and PtNAC109/PtORE1 to their target gene promoter BIFUNCTIONAL NUCLEASE1 (PtBFN1) (Supplemental Figure 17), suggesting that PtRD26IR affects leaf senescence possibly by impairing the activities of multiple hub Sen-NAC TFs. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays in N. benthamiana leaves and split luciferase complementation (SLC) assays further supported that PtRD26IR and PtRD26 interacted and were colocalized in the nucleus (Figure 6, B–C).

Figure 6.

PtRD26IR physically interacts with PtRD26. (A) Analysis of interactions between PtRD26IR and PtRD26 by Y2H. Plasmids of the bait and prey pairs were cotransfected into yeast cells and selected on SD/-LW and SD/–LWHA medium, respectively. The transferred yeast cells were diluted with 1x, 10x, 100x, or 1000x gradients. (B) Analysis of the interactions between PtRD26IR and PtRD26 by BiFC in N. benthamiana leaves. Leaves were stained with 2 μg/mL DAPI to indicate the nucleus. A positive nuclear signal is indicated with a red arrow. Bar = 50 μm. (C) Analysis of interactions between PtRD26IR and PtRD26 by split luciferase complementation assays. An equal volume of A. tumefaciens GV3101 cells harboring DNA constructs were mixed and infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves. The leaves were sprayed with D-Luciferin potassium salt and used for fluorescence detection by a CCD camera. Bar = 1 cm.

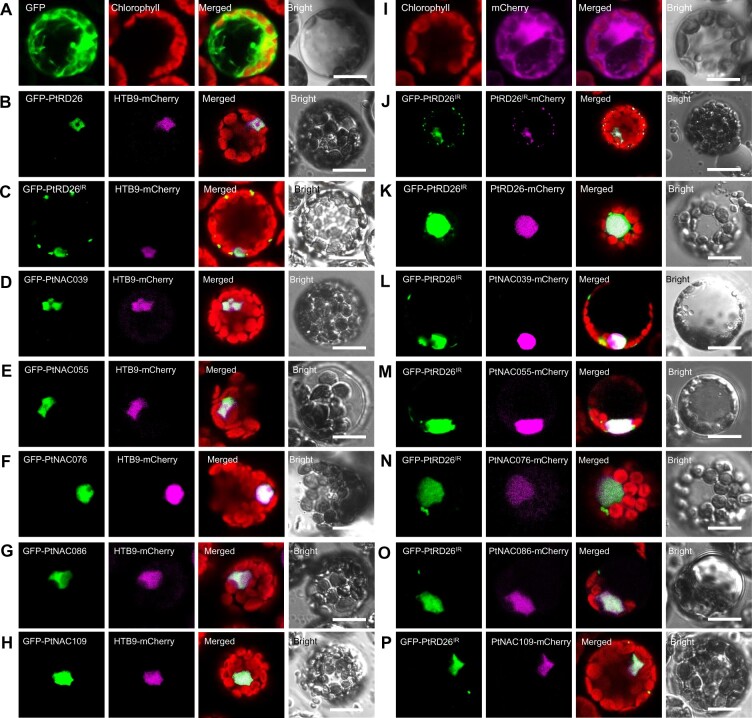

Given that PtRD26IR lacks a putative nuclear localization signal (Figure 4B), the BiFC and SLCA results prompted us to propose that PtRD26IR may be translocated to the nucleus by interacting with PtRD26 or other Sen-NAC TF members. To test this possibility, we used fluorescent protein fusions to explore the subcellular localization of PtRD26 and other hub NAC TFs and PtRD26IR in P. tomentosa mesophyll protoplasts (Figure 7). We co-transfected the protoplasts with 35Spro:GFP-PtRD26/PtRD26IR or 35Spro:GFP-PtNAC039/055/076/086/109 and nuclear marker plasmid 35Spro:HTB9-mCherry. As expected, each of the six full-size hub NAC TFs colocalized with the histone 2B variant HTB9 in the nucleus (Figures 7, B–D to 7H). In contrast, PtRD26IR alone was located in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Figure 7, C and J). Interestingly, in the presence of any one of the hub NAC TFs, GFP-PtRD26IR was located exclusively in the nucleus, as evidenced by the nuclear colocalization of GFP-PtRD26IR with each of the hub NAC TFs fused with mCherry (Figure 7, K–P).

Figure 7.

PtRD26IR is translocated from the cytoplasm into the nucleus by association with multiple Sen-NAC TFs. (A) Empty vectors only with GFP or mCherry (I) were transiently expressed in P. tomentosa mesophyll protoplasts and used as the controls. (B–H) Subcellular localization of PtRD26IR and six Sen-NAC TFs: PtRD26 (B), PtRD26IR (C), PtNAC039 (D), PtNAC055 (E), PtNAC076 (F), PtNAC086 (G), and PtNAC109 (H). Each NAC TF was fused with GFP and co-transfected with nuclear marker HTB9-mCherry into P. tomentosa mesophyll protoplasts. (J–P) Translocation of PtRD26IR from the cytoplasm (J) into the nucleus by co-expressing full-length hub Sen-NAC TFs (K-P). Each NAC TF was fused with GFP and mCherry, respectively, and co-transfected into P. tomentosa mesophyll protoplasts. All bars = 5 μm.

Therefore, it is likely that PtRD26IR is translocated from the cytoplasm into the nucleus by forming heterodimers with PtRD26 or its homologs, and competitively attenuates the DNA-binding activity of PtRD26 or other NAC-TF homodimers.

U2A2A and U2A2B participate in the AS event of PtRD26IR during leaf senescence

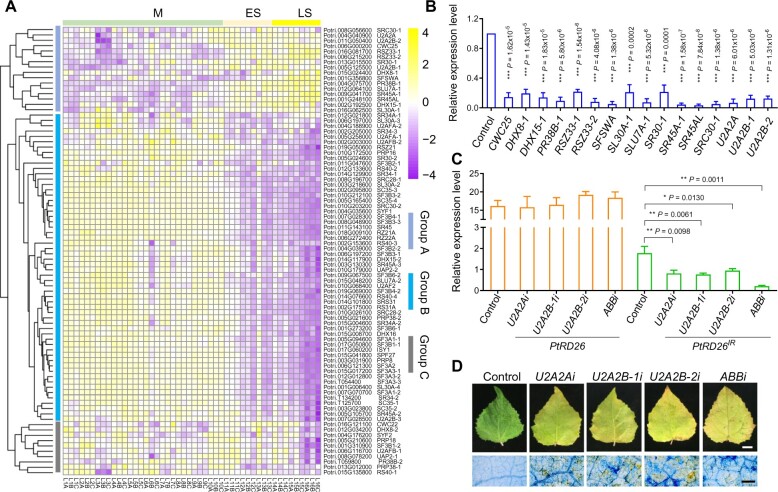

Because AS events are determined by transacting splicing factors (SFs) (Fu and Ares, 2014; Lee and Rio, 2015), we sought to identify the SFs possibly involved in the AS event of PtRD26IR and study their functions in leaf senescence (Supplemental Data Set 6). Because the production of PtRD26IR is senescence-regulated, we first characterized senescence-associated SFs. We first performed a hierarchical cluster analysis of 84 annotated SFs during leaf senescence using the pheatmap package in R software (Deng et al., 2014). Based on their expression patterns, the SFs were categorized into three groups: A, B and C (Figure 8A). In group A, the transcript levels of 16 SFs increased as leaves aged, and these SFs were designated as senescence-associated splicing factors (Sen-SFs) (Figure 8A). In group B, the transcript levels of 58 SFs declined as leaf senescence progressed. Ten SFs with expression patterns that had no clear relationship with leaf senescence were categorized into group C.

Figure 8.

Identification and functional analysis of senescence-associated splicing factors in P. tomentosa. (A) Cluster analysis of 84 splicing factors (SFs) using RNA-Seq data. SFs were mainly divided into three groups: A, B, and C. M, mature stage; ES, early senescence stage; LS, late senescence stage. (B) qRT–PCR analysis of the transcripts of 16 Sen-SFs in P. tomentosa protoplasts with individually silencing corresponding gene by artificial microRNA (amiRNA) technology. Untransformed protoplasts were used as a negative control (set as 1). (C) Silencing of SFs PtU2A2A, PtU2A2B-1 and PtU2A2B-2 decreases the abundance of PtRD26IR but not PtRD26. Silencing a single gene (U2A2Ai, U2A2B-1i, and U2A2B-2i) or three genes simultaneously (ABBi) by amiRNA. Untransformed protoplasts were used as a negative control. (D) Silencing of PtU2A2A, PtU2A2B-1 or PtU2A2B-2 promotes leaf senescence in dark conditions (top). Trypan blue staining of the treated leaves to show dead or dying cells as blue-colored patches (bottom). P values in (B) and (C) are from two-tailed Student’s t test (Supplemental File 1). Bar in (D) = 2 cm (top panels) and 500 μm (bottom panels).

Because IR events are typically not a byproduct of faulty splicing but rather a tightly regulated and extremely active process (Wong et al., 2013; Middleton et al., 2017), we speculated that Sen-SFs in group A might be more likely than those in groups B and C to participate in the AS event of PtRD26. To test this possibility, we performed artificial miRNA (amiRNA)-mediated gene silencing of 16 Sen-SFs in poplar protoplasts to assess their effects on AS of PtRD26IR. As shown in Figure 8B, the expression levels of 16 Sen-SFs were decreased significantly, with reductions ranging from ∼79% to 97% compared to the vector control, indicative of effective gene silencing (Figure 8B).

To identify candidate Sen-SFs involved in PtRD26IR induction, we measured the relative expression levels of PtRD26IR and PtRD26. We found that silencing of PtU2A2A, PtU2A2B-1 or PtU2A2B-2 (U2 auxiliary factor large subunit A or B) (Brosi et al., 1993), significantly decreased the transcript levels of PtRD26IR. In contrast, it had no evident effect on PtRD26 (Figure 8C), suggesting the involvement of PtU2A2A, PtU2A2B-1, and PtU2A2B-2 in the IR event of PtRD26IR. To explore the involvement of PtU2A2A, PtU2A2B-1, and PtU2A2B-2 in leaf senescence, we transiently silenced these Sen-SFs separately or simultaneously in P. tomentosa leaves. As expected, silencing of PtU2A2A, PtU2A2B-1, and/or PtU2A2B-2 accelerated leaf senescence in the dark conditions compared to that of the control (Figure 8D). This was evidenced by reduced chlorophyll contents, increased PtSAG12 expression, and the presence of dead or dying cells (Figure 8D;Supplemental Figure 18). These findings demonstrate that PtU2A2A, PtU2A2B-1, and PtU2A2B-2 function as negative regulators of leaf senescence.

Discussion

Leaf senescence is a highly complex genetic program that is finely controlled by multiple layers of regulation, including transcriptional, posttranscriptional, translational, and posttranslational regulation (Woo et al., 2019). Temporal profiling of gene expression during leaf senescence in annual and perennial plants has revealed highly ordered molecular events involving temporal coordination of the expression of thousands of genes during aging (Andersson et al., 2004; Breeze et al., 2011; Woo et al., 2019). TFs such as NAC and WRKY are key central factors that modulate transcriptional changes during leaf senescence (Woo et al., 2019). In this study, we have identified 3,459 ASAGs in the perennial plant P. tomentosa using high-resolution time course transcriptome analysis (Figure 1), which provided a comprehensive picture of transcription regulation during leaf senescence in P. tomentosa. P. tomentosa is an indigenous poplar tree species in China that plays a key role in the establishment of plantation forests along the Yellow River to provide ecological and environmental protection (Du et al., 2012). In accordance with the findings in annual plants (Kim et al., 2018), our gene co-expression network analysis identified a collection of poplar hub Sen-TFs, among which Sen-NAC TFs play critical roles in regulating leaf senescence in the autumn (Figure 2). In this study, we focused on the investigation of one of the hub Sen-NACs, PtRD26, due both to its extremely high expression in senescent leaves (Supplemental Data Set 1) and to its functional importance in stress-induced leaf senescence (Woo et al., 2019). Genetic experiments and biochemical assays demonstrated that PtRD26 functions as a common inducer of leaf senescence by activating a variety of senescence-related pathways and genes, such as PtEIN3, PtORE1, and PtNAP, three important Sen-TFs in leaf senescence regulation (Guo and Gan, 2006; Kim et al., 2009; Li et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2014).

As an important posttranscriptional regulatory mechanism, AS generates multiple mRNA transcripts from a single gene, and this can lead to an increase in transcriptome plasticity and proteome diversity (Fu and Ares, 2014; Lee and Rio, 2015). AS events can be mainly classified into five categories: IR, skipping exon and mutually exclusive exons, as well as alternative 5′-splice sites and alternative 3′-splice sites (Wang et al., 2015). Of all AS events, IR is the prevalent mode of AS in plants and represents ∼40% of all AS events in Arabidopsis. It is involved in the response to environmental stresses such as cold as well as developmental processes (Marquez et al., 2012). Cold treatment causes dynamic changes in AS events, and loss-of-function of a U2B-LIKE splice factor leads to IR of PIF7 and HYH (Calixto et al., 2018). Interestingly, the Arabidopsis u2b-like mutant displays hypersensitivity to cold stress, suggesting that AS is linked to stress responses. COβ, an IR version of CONSTANS, interacts with and stabilizes CONSTANS protein and sustains its diurnal accumulation dynamics during photoperiodic flowering (Gil et al., 2017), indicating that AS is linked to development.

Accumulating evidence indicates that AS is widespread and diversified across Populus species and likely contributes to environmental adaptation and the development of specialized tissues such as secondary xylem (Li et al., 2012; Bao et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2017). Because leaf senescence is characterized by global cellular and molecular changes, alternative splicing is a potential regulatory mechanism for this highly programmed event. In this study, we presented several lines of evidence demonstrating the importance of AS in the regulation of leaf senescence. First, we identified a splicing variant of PtRD26 that can produce a truncated protein PtRD26IR and showed that PtRD26IR functions as a negative regulator of leaf senescence. Interestingly, PtRD26IR emerges only at senescent leaves and gradually accumulates upon leaf aging (Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure 9). Second, we found that PtRD26IR interferes with PtRD26’s binding activity by forming PtRD26-PtRD26IR heterodimers (Figures 5 and 6). It is likely that the PtRD26-PtRD26IR association might prevent the formation of PtRD26 homodimers that is critical for the DNA binding activity of PtRD26. Third, PtRD26IR is also able to interact with other hub Sen-NAC TFs, such as PtNAC055, PtNAC086, and PtNAC109 (Supplemental Figure 15), and impairs their DNA binding activities (Supplemental Figure 17), suggesting that the splicing variant might exert a broader action through the formation of heterodimers with multiple Sen-NAC TFs.

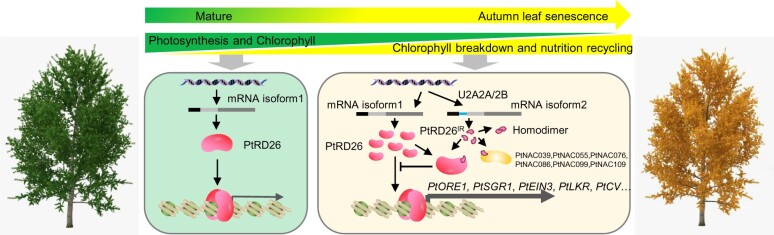

Interestingly, our study reveals that PtRD26 regulates the functions of other Sen-TFs either directly by binding to their promoters (Figure 3) or indirectly through protein-protein interactions using its own splicing variant, PtRD26IR (Supplemental Figure 17, B–D), which forms a multiply-interlocked feed forward loop that finely tunes the progression of leaf senescence. The occurrence of PtRD26IR might function as an effective braking system to coordinate the progression of leaf senescence (Figure 9). As leaves age, a large number of Sen-TFs are induced to form positive feedback regulation loops. Nevertheless, lack of an effective braking system would quickly drive the senescence process out of control or in a disordered state, which would not be conducive to the stepwise biomolecule degradation as well as the gradual return of nutrients. Given that many members of eukaryotic TFs form functional homodimers or heterodimers to increase DNA binding affinity and specificity, it might be a general mechanism that the PTC-caused truncated proteins derived from TFs, such as NAC, MYB, or WRKY family TFs, act as dominant negative regulators to repress the activity of the related TFs in plants (Lin et al., 2017).

Figure 9.

A proposed model illustrating senescence-associated alternative splicing of PtRD26 in regulation of autumn leaf senescence. As leaves age, the abundance of the PtRD26 transcript increases, leading to chlorophyll breakdown, the decrease in photosynthesis and nutrition recycling by directly regulating transcripts of several core SAGs, including PtORE1, PtEIN3, PtSGR1, PtLKR, and PtCV. At the same time, expression levels of splicing factors U2A2A/2B increase, resulting in the generation of alternative splicing variant PtRD26IR. PtRD26IR interacts with PtRD26 and other hub Sen-NAC TFs such as PtNAC039 to form heterodimers and in turn attenuate their activities, likely by disrupting their binding to target genes, thus slowing the progression of autumn leaf senescence.

We also profiled the expression patterns of 84 SFs during autumn leaf senescence and found that 74 of them (∼88%) show altered expression as leaf aging, with 16 being senescence-induced (Figure 8A). Knockdown of three Sen-SFs, U2A2A, U2A2B-1, and U2A2B-2, decreases the production of PtRD26IR and promotes leaf senescence (Figure 8, C–D), highlighting the functional importance of specific SFs in this process. Different from previous report on the function of U2B in cold-induced IR events in Arabidopsis (Calixto et al., 2018), our study showed that mutations of U2A2A/2B SFs decrease the IR event of PtRD26IR during leaf senescence, suggesting that they inhibit intron splicing of PtRD26. Similar findings have been reported for splicing factor U2AF65 in 293A (human embryonic kidney) cells, and for reduced expression of U2AF65 decreases intron retention but promotes exon inclusion in SMN2 (spinal muscular atrophy-related survival motor neuron) (Cho et al., 2015), indicative of multiple regulatory strategies of SFs in alternative splicing. In summary, our poplar leaf transcriptome data provide an informative resource for the understanding of transcriptional programs underlying autumn leaf senescence in perennial plants. Our findings suggest that AS, a posttranscriptional event, provides another layer of regulation to fine-tune the appropriate initiation and progression of leaf senescence (Figure 9).

Recently, a rice NAC-TF, ONAC054, was shown to participate in ABA-induced leaf senescence by directly activating ABA INSENSITIVE5 (OsABI5) and other senescence-associated genes (Sakuraba et al., 2020). Interestingly, the ONAC054 transcript (ONAC054α) has an alternatively spliced form, ONAC054β, which encodes a small truncated protein lacking the C-terminal transmembrane domain (TMD). Overexpression of ONAC054α or ONAC054β promotes leaf senescence, suggesting that this NAC AS variant is a positive regulator of leaf senescence in annual plants. In Arabidopsis, loss of function of spliceosome protein U11-48K was also reported to delay leaf senescence (Xu et al., 2016). By analyzing high-resolution time course transcriptome data in Arabidopsis (Woo et al., 2016), we identified 1405 genes that were differentially alternatively spliced (DAS) during leaf senescence (Supplemental Figure 7 and Supplemental Data Set 4). Together with our study, these findings demonstrate that AS plays a critical role in the regulation of leaf senescence in both annual and perennial plants.

Notably, both changes in the activity of splicing factors and the generation of splicing variants also impact cellular senescence and aging phenotype in animals (Deschenes and Chabot, 2017). For example, depletion of splicing factor SFA-1 compromises longevity contributed by caloric restriction, whereas overexpression of SFA-1 is sufficient to increase lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans (Heintz et al., 2017). Intriguingly, modulation of target splicing factor expression by the small molecule resveralogues, a resveratrol-like compound, rescues multiple features of cellular senescence in human primary fibroblasts, providing a new perspective for anti-aging (Latorre et al., 2017). Therefore, AS-mediated regulation of senescence might be a conserved mechanism in plants and animals (Wu et al., 2019). Nevertheless, future studies need to be conducted to address the cause-and-effect question, that is, whether the senescence process drives splicing changes, or vice versa.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Leaf samples were collected at 16 time points from September 22 to November 17, 2018, from three field-growing poplar trees (Populus tomentosa) (35-year-old) at the campus of Beijing Forestry University (40.0068° N, 116.3458° E). Approximately 50 leaves detached from five branches for each replicate tree at one time point were pooled and used for extraction of total RNA and measurement of chlorophyll contents with a SPAD Chlorophyll Meter (SPAD-502 Plus; Konica Minolta).

RNA-Seq and identification of hub Sen-TFs

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Cat. NO. 15596-026, Invitrogen). The quality and quantity of RNA were detected using an IMPLEN NanoPhotometer (GmbH). RNA-Seq data were generated with an Illumina HiSeq 2000 system at Novogene Ltd. (Beijing, China). Raw reads (fastq format) were trimmed and filtered through in-house perl scripts (Novogene Ltd., China). After processing, 2.485 billion high-quality reads (average Qphred > 20 = 97.41%) with 372.8 Gb clean bases were generated. The cleaned reads were mapped to the Populus trichocarpa reference genome v3 using the Hisat2 algorithm (Kim et al., 2015). The mapped genes were used for identifying the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and clustering analysis. The reads per kilobase per million (FPKM) values were calculated to measure gene expression levels (Mortazavi et al., 2008), and the R package DESeq was implemented for variance stability measurement and the identification of differentially expressed genes (Anders and Huber, 2010). Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed to generate the dendrogram (Datta and Datta, 2003). Hub Sen-TFs were identified by calculating the correlation coefficient and expression similarity of gene pairs using the R program (WGCNA package, R team) (Zhang and Horvath, 2005; Langfelder and Horvath, 2008). Cytoscape software was used for network analysis and visualization (https://cytoscape.org/) (Shannon et al., 2003). A heatmap was generated by using the pheatmap R program and Heml 1.0 software (Deng et al., 2014). rMATS tool was applied to identify differential alternative splicing variants during Populus and Arabidopsis leaf senescence (Shen et al., 2014).

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qRT–PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Cat. NO. 15596-026, Invitrogen), and first-strand cDNA samples were generated using a cDNA synthesis kit (Life Sciences, Promega). qRT–PCR was performed using Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR Systems (ABI, Carlsbad, CA). PCR was performed in a 20-µL reaction mixture containing 1-μL cDNA, 0.3 μM of each primer, and 10 μL SYBR PreMix Plus (Tiangen Biotech, China). The PCR cycling parameters were initial incubation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 35 s (Wang et al., 2014). Three biological replicates were performed for all qRT–PCR experiments. The primers used for qRT–PCR were described in Supplemental Data Set 7.

Construction of amiRNA plasmids to silence splicing factors

To knock down the levels of splicing factors in P. tomentosa protoplasts, we used an artificial miRNA silencing system (pRS300), which has been widely used to specifically silence single or multiple genes of interest in plants (Schwab et al., 2006). The primers were designed using the online program Web MicroRNA Designer (WMD3) (http://wmd3.weigelworld.org/cgi-bin/webapp.cgi) and were listed in Supplemental Data Set 7.

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) assay

VIGS-NbUPF1 was constructed by cloning NbUPF1 cDNA fragments into VIGS vector pTRV2. The primers used for DNA construct were listed in Supplemental Data Set 7 online. The VIGS assay was performed as previously described (Liu et al., 2002).

Identification of PtRD26IR by LC-MS/MS

A plant total protein extraction kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai) was used for extracting proteins from mature or senescent P. tomentosa leaves. The total proteins were separated using 15% SDS–PAGE, and proteins in the range of 15 kD to 4.6 kD were recovered for further mass spectrometry analysis (Beijing Qinglian Biotech Co., Ltd.). Samples were quantified and in-gel digested using a 1:50 (w/w) endoproteinase:trypsin solution, incubated at 37°C for 20 h, and resuspended in 0.1% formic acid loading buffer. Products were analyzed using a liquid chromatography tandem triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS, Easy-nLC 1000, Q Exactive, Thermo Fisher). Analyst software (Proteome Discoverer1.4) was used to analyze the data.

Preparation and transfection of P. tomentosa mesophyll protoplasts

Fully expanded healthy leaves were cut into 1- to 2-mm fine strips and digested in an enzyme solution [2% (w/v) cellulase R10 (AOV0105, Yakult, Japan), 0.8% (w/v) macerozyme R10 (AOV0098, Yakult, Japan), 0.5% (w/v) pectinase Y-23 (AOV0094, Yakult, Japan), 0.6 M d-mannitol, 10 mM CaCl2, 20 mM KCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM MES-KOH (pH 5.7) and 0.1% (w/v) BSA] in the dark for 5 h with gentle shaking (55 rpm), modified from protocols as described previously (Yoo et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2012; Tan et al., 2013). The protoplasts were harvested by filtering through a 400-mesh sieve (30 μm pore diameter), washed twice with W5 solution [125 mM CaCl2, 154 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MES-KOH (pH 5.7)], and suspended in transfection buffer [15 mM MgCl2, 4 mM MES-KOH (pH 5.7), 0.6 M d-mannitol] to a concentration of 1 × 107 protoplasts/mL. For the transfection assay, 10 μg plasmid (1 μg/μL) was added to 100 μL protoplast suspension, after which 110 μL PEG/Ca2+ solution [40% (w/v) PEG, 0.1 M CaCl2, 0.2 M d-mannitol] was added. The mixture was incubated at 23°C for 30 min in dark, and 440 μL W5 solution was added to stop the reaction. The protoplasts were collected by centrifugation at 100 g for 1 min and suspended in 1 mL of W5 buffer in a 100-mm2 petri dish at 23°C for 18 h under dark conditions.

Phylogenetic analysis

The amino acid sequences of full-length or dimerization region of Sen-NAC TFs were aligned and analyzed with ClustalX 2.1 algorithms, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed and visualized using MEGA 7 software with the neighbor-joining algorithm and bootstrap method of 1,000 replications (Kumar et al., 2016). Text files of the alignments used for Figure 2C and Supplemental Figure 16 are presented in Supplemental Files 2 and 3.

Yeast two-hybrid assays

pGADT7 and pGBKT7 vectors (Clontech) were digested by EcoRI and BamHI together and used to create activation domain (AD) and (DNA-banding domain (BD)) constructs, respectively. Genes inserted into these vectors are presented in Supplemental Data Set 7. Transformation of yeast strain AH109 cells was performed with the BD Matchmaker system (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and confirmed by streaking the clones on a double-deficient medium (-LW, -Leu/-Trp). Positive clones were cultured and streaked on quadruply deficient media (-LWHA, -Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade) to allow detection of in vitro interactions.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays

pUC-SPYNE/pUC-SPYCE (nYFP/cYFP) and pSPYNE-35S/pSPYCE-35S (nYFP/cYFP) vectors were used for transformation of P. tomentosa protoplasts and infiltration of tobacco leaves via Agrobacterium tumefaciens, respectively (Hu, 2002). Coding regions of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR were amplified and cloned into SmaI-digested vectors using In-Fusion Premix (Lot#1710367A, TAKARA). A polyethylene glycol-calcium (PEG/Ca2+) transfection method was used for poplar protoplast incubation (Yoo et al., 2007), and HTB9:mCherry was simultaneously transferred into the poplar protoplasts as a nuclear marker. Leaves were stained with 2 μg/mL of 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min to indicate nuclei. A Zeiss 780 laser scanning confocal microscope was used for fluorescence detection (GFP, excitation 488 nm, emission 505–540 nm; YFP, excitation 514 nm, emission 518–582 nm; DAPI, excitation 405 nm, emission 430–480 nm; mCherry, excitation 594 nm, emission 598–684 nm).

Split luciferase complementation assays (SLCAs)

pCAMBIA1300-nLUC and pCAMBIA1300-cLUC vectors were used for SLCA (Chen et al., 2008). The coding regions of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR were cloned into double digested vectors (KpnI/SalI) using In-Fusion Premix (Lot#1710367A, TAKARA). Overnight-cultured A. tumefaciens GV3101 cells (BC308-01, Biomed, China) harboring the constructed plasmids were resuspended (OD600 = 0.5) in infiltration buffer (10 mM MES pH5.8, 10 mM MgCl2, and 100 μM acetosyringone) for 3 h in dark before infiltration. Equal volumes of the nLUC and cLUC suspensions were mixed and infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves, which were placed in the dark for 24 h and then transferred into the light for 48 h. Before fluorescence detection by a CCD camera (Vilber NEWTON7.0), the leaves were sprayed with 0.32 mg/mL d-Luciferin potassium salt in 0.1% Triton X-100 (Gold Biotechnology).

Effector/reporter-based transactivation assay

pGreenII 0800-LUC and pGreen 62-SK vectors were used for the effector/reporter-based transactivation assay as described previously (Hellens et al., 2005; Fujikawa and Kato, 2007). The 2.0-kb promoter regions of PtORE1 and PtSGR1 were cloned into the pGreen II 0800-LUC vector (effector). The coding regions of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR were cloned into the pGreen 62-SK vector (reporter). Equal volumes of the suspensions were mixed and infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves, which were placed in the dark for 24 h and then transferred into the light for 48 h, and detected by a CCD camera (Vilber NEWTON7.0).

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

To detect GFP-PtRD26 and GFP-PtRD26IR, total protein extracted from the transfected leaves of P. tomentosa or N. benthamiana was immunoblotted with an anti-GFP monoclonal antibody at a dilution of 1:2000 (Lot#AE012, ABclonal, China). To determine levels of endogenous PtRD26 and GFP-PtRD26IR, the protein-specific polypeptide (aa 2-13) was selected as an immunogen to develop an anti-RD26IR monoclonal antibody by the company ABclonal Technology Co., Ltd. (China). Antibody specificity was examined by immunoblot using Escherichia coli recombinant proteins fused with His tag from the N-termini (∼160 aa) of PtRD26 and 10 PtRD26IR-interacting NAC TFs (Supplemental Figure 12). To detect GFP-PtRD26IR in Arabidopsis, 5-d-old ER8pro:GFP-PtRD26IR seedlings were treated with 50 μM β-estradiol for 3 h and used for immunoblotting (Protein marker, Real-Times Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP experiments were performed as described previously with minor modifications (Lee et al., 2017). Briefly, the transfected P. tomentosa protoplasts (∼1 × 107) were centrifuged at 1,500 g for 2 min at room temperature. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was fixed in 1% formaldehyde by placing it on a rotor (12 rpm) for 10 min at RT. Next, 2 M glycine was added for 5 min to quench the cross-linking reaction. After centrifugation at 1,500 g for 5 min at 4°C, the pellet was washed twice with cold sterile water and used for isolation of nuclei. The sonicated chromatin supernatant (300 μL) was diluted, and 50 μL salmon sperm DNA/protein A agarose beads (Upstate) were added for preclearing at 4°C for 1 h with gentle rotation (12 rpm). 10 μL of mouse anti-GFP monoclonal antibody was added, and 20 μL of protein A agarose beads were added to the “no antibody control.” After incubation at 4°C overnight with gentle rotation (12 rpm), the beads were washed with low-salt wash buffer, high-salt wash buffer, and Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (Lee et al., 2017). Elution and reverse crosslinking with 5 M NaCl were performed as previously described (Lee et al., 2017). The eluates were treated with 1 μL of 1 mg/mL Proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 1 h and extracted with an equal volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), and then ethanol precipitated with 2 μL of 20 mg/mL glycogen. The purified DNA was resuspended in 30 μL of distilled water and stored at −20°C. Enrichment of DNA fragments was detected by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using the primers listed in Supplemental Data Set 7.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

The full-length coding regions of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR were produced by RT–PCR and used for developing the DNA constructs to pET32a for the expression of recombinant proteins in E. coli. Purification of PtRD26 (amino acids 1-343) and PtRD26IR (amino acids 1-62) was conducted according to the protocol included with the HisPur Ni-NTA Spin Purification Kit (Lot #88228, Thermo Scientific). EMSA experiments were performed according to the user guide from the LightShift™ Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Lot#20148, Thermo Scientific). Briefly, the binding reaction was carried out in a total volume of 20 μL by incubation of an appropriate amount of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR with 20 fmol of biotin-labeled probe DNA and 1 μg poly (dI-dC) in a reaction buffer (25 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% [v/v] glycerol, 1 mM DTT) at room temperature for 30 min. The binding reaction products were resolved on a 6% polyacrylamide gel run in 0.5 × TBE buffer. 5′-biotin-labeled oligonucleotides of PtORE1, PtNAP, PtEIN3, PtSGR1, PtCV, PtLKR, PtLOX2, and PtACS6 were synthesized and used as probes in EMSA (Supplemental Data Set 7).

Statistical analysis

The values shown in the figures are expressed as means ± SD. Two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare groups. Results of statistical analyses are provided in Supplemental File 1.

Accession numbers

Genes mentioned in the study are as follows: PtRD26 (Potri.001G404100), PtORE1/PtNAC109 (Potri.012G001400), PtNAP/PtNAC086 (Potri.008G089000), PtEIN3 (Potri.004G197400), PtSGR1 (Potri.003G119600), PtCV (Potri.006G248300), PtLKR (Potri.006G134300), PtLOX2 (Potri.009G022400), PtACS6 (Potri.001G099400), PtSAG12 (Potri.004G055900), NbSAG12 (ADV41672), PtNAC055 (Potri.005G180200), PtNAC076 (Potri.007G065400), PtNAC105 (Potri.011G123300), PtBFN1(Potri.011G044500), SRC30-1 (Potri.008G056600), U2A2A (Potri.004G040900), U2A2B-1 (Potri.005G125500), U2A2B-2 (Potri.006G000200), CWC25 (Potri.006G000200), RSZ33-1 (Potri.016G081700), RSZ33-2 (Potri.006G215200), SR30-1 (Potri.013G015500), PR38B-1 (Potri.004G075700), SLU7A-1 (Potri.012G064100), SR45A-1 (Potri.009G041700), SR45AL (Potri.001G248100), DHX15-1 (Potri.002G192500), SL30A-1 (Potri.016G062500), DHX8-1 (Potri.015G024400), SFSWA (Potri.001G356800), AtPRD26/ANAC072 (AT4G27410), SAG12 (AT5G45890), and HTB9 (AT3G45980).

Data availability

High-resolution temporal profile data have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) with the accession number PRJNA561520.

Supplemental data

Supplemental Figure 1. Venn Diagrams Showing the Overlaps between Autumn Senescence Associated Genes (ASAGs) in Populus and SAGs in Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure 2. KEGG Pathway and GO Enrichment Analyses of ASAGs in Populus.

Supplemental Figure 3. The Number of Hub Sen-TFs Identified in 31 TF Families.

Supplemental Figure 4. Overexpression of Three Hub Sen-NAC TFs, PtRD26, PtNAC055 and PtNAC076, Accelerates Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure 5. Schematic Diagrams of Putative PtRD26 Binding Sites (Arrows) in the Promoters of Candidate Target Genes.

Supplemental Figure 6. Confirmation of the Intron-Retained Alternative Splicing Event of PtRD26 by Sequencing and Genotyping.

Supplemental Figure 7. Identification of the Genes that Are Differentially Alternatively Spliced during Leaf Senescence in Populus and Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure 8. Validation of the Intron-Retained Alternative Splicing Event of PtRD26 using RNA-Seq Data.

Supplemental Figure 9. qRT–PCR Analysis of PtRD26 and PtRD26IR at Different Stages.

Supplemental Figure 10. Amino Acid Sequence Alignment of PtRD26 with 10 Arabidopsis NAC TFs.

Supplemental Figure 11. Premature Termination Codon (PTC)-containing PtRD26IR Is Not a Target of NMD.

Supplemental Figure 12 . Validation of Anti-PtRD26IR Monoclonal Antibody Specificity via Immunoblot.

Supplemental Figure 13. Inducible Overexpression of PtRD26IR Represses PtRD26-Induced Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure 14. PtRD26IR Inhibits the Binding of PtRD26 to Its Downstream Targets.

Supplemental Figure 15. PtRD26IR Physically Interacts with Hub Sen-NAC TFs.

Supplemental Figure 16. Phylogenetic Tree Analysis of 32 NAC TFs and Heat Maps Showing Their Expression Patterns during Leaf Senescence.

Supplemental Figure 17. PtRD26IR Disrupts the Binding Activities of PtORE1, PtNAP and PtNAC055 to the Downstream Target Promoter of PtBFN1.

Supplemental Figure 18. Chlorophyll Contents and SAG12 Gene Expression in PtU2A2Ai, PtU2A2B-1i, PtU2A2B-2i, or ABBi Leaves.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Expression and Annotation of ASAGs.

Supplemental Data Set 2. List of the Hub TFs.

Supplemental Data Set 3. Expression and Annotation of NAC TFs.

Supplemental Data Set 4. Identification of Sen-ASVs in Populus and Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Data Set 5. List of the Peptides Identified by LC-MS/MS.

Supplemental Data Set 6. Expression and Annotation of Splicing Factors.

Supplemental Data Set 7. Primers Used in This Study.

Supplemental File 1. Statistical Analysis Tables.

Supplemental File 2. Sequence Alignment Used to Produce the Phylogenetic Tree in Figure 2C.

Supplemental File 3. Sequence Alignment Used to Produce the Phylogenetic Tree in Supplemental Figure 16.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Hong Gil Nam (Center for Plant Aging Research, IBS, Korea) for valuable advice and discussions, and thank Prof. Jingchu Luo (Peking University, China), Prof. Steven Strauss (Oregon State University, USA), Prof. Hye Ryun Woo (DGIST, Korea), and Prof. Xiangyang Kang (Beijing Forestry University) for kindly discussions, Prof. Haidong Li (Center of Biomedical Analysis, Tsinghua University, China) for assisting in confocal microscopy analysis, and thank Dr. Wei Yan and Dr. Yajie Pan (SUSTech, China) for constructive comments. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31970196 to Z.L.; 31900173 to H.W.; 31770649 to X.X.; 31570286 to H.G.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2019YFA0903904 to H.G.), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (KQTD20190929173906742 to H.G.), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant nos. 2019M650516 to H.W. and 2019M650514 to Y.Z.), and the startup funding for plant aging research from “Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Tree Breeding by Molecular Design, Beijing Forestry University.”

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Z.L. and H.G. conceived the project and designed the experiments; H.W., X.W., W.L., W.Y., and X.X. designed part of the experiments; H.W. carried out most of the experiments; Y.Z. and Z.L. conducted Y2H and EMSAs; H.W., T.W., Q.Y., and Y.Y. prepared the poplar protoplasts and transient transform; H.W., Z.L., and B.L. analyzed the RNA-Seq data; Z.L., H.G., and H.W. wrote the manuscript with input from all coauthors.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plcell) is Zhonghai Li (lizhonghai@bjfu.edu.cn).

References

- Anders S, Huber W (2010) Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 11: R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson A, Keskitalo J, Sjodin A, Bhalerao R, Sterky F, Wissel K, Tandre K, Aspeborg H, Moyle R, Ohmiya Y, et al. (2004) A transcriptional timetable of autumn senescence. Genome Biol 5:R24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciga-Reyes L, Wootton L, Kieffer M, Davies B (2006) UPF1 is required for nonsense‐mediated mRNA decay (NMD) and RNAi in Arabidopsis. Plant J 47:480–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Ospina L, Moison M, Yoshimoto K, Masclaux-Daubresse C (2014) Autophagy, plant senescence, and nutrient recycling. J Exp Bot 65:3799–3811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ay N, Irmler K, Fischer A, Uhlemann R, Reuter G, Humbeck K (2009) Epigenetic programming via histone methylation at WRKY53 controls leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 58:333–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S, Riano-Pachon DM, Mueller-Roeber B (2008) Transcription factors regulating leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biol 10:63–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao H, Li E, Mansfield SD, Cronk QC, El-Kassaby YA, Douglas CJ (2013) The developing xylem transcriptome and genome-wide analysis of alternative splicing in Populus trichocarpa (black cottonwood) populations. BMC Genomics 14:359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalerao R, Keskitalo J, Sterky F, Erlandsson R, Bjorkbacka H, Birve SJ, Karlsson J, Gardestrom P, Gustafsson P, Lundeberg J, et al. (2003) Gene expression in autumn leaves. Plant Physiol 131:430–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeze E, Harrison E, McHattie S, Hughes L, Hickman R, Hill C, Kiddle S, Kim YS, Penfold CA, Jenkins D, et al. (2011) High-resolution temporal profiling of transcripts during Arabidopsis leaf senescence reveals a distinct chronology of processes and regulation. Plant Cell 23:873–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosi R, Groning K, Behrens SE, Luhrmann R, Kramer A (1993) Interaction of mammalian splicing factor SF3a with U2 snRNP and relation of its 60-kD subunit to yeast PRP9. Science 262:102–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JW, Simpson CG, Marquez Y, Gadd GM, Barta A, Kalyna M (2015) Lost in translation: pitfalls in deciphering plant alternative splicing transcripts. Plant Cell 27:2083–2087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calixto CPG, Guo W, James AB, Tzioutziou NA, Entizne JC, Panter PE, Knight H, Nimmo HG, Zhang R, Brown JWS (2018) Rapid and dynamic alternative splicing impacts the Arabidopsis cold response transcriptome. Plant Cell 30:1424–1444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zou Y, Shang Y, Lin H, Wang Y, Cai R, Tang X, Zhou JM (2008) Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay for protein-protein interactions in plants. Plant Physiol 146:368–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]