Abstract

Rationale

Loss of function mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes is the primary genetic defects in high-risk hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC). Cytotoxic chemotherapy and anti-inflammatory drugs are potential treatment options. These treatment options lead to systemic toxicity, acquired tumor resistance and the emergence of drug-resistant stem cells. A colonic epithelial cell culture model expressing the relevant genetic defects in chemo-resistant stem cells provides a relevant experimental system for HNPCC.

Objective

To develop a colonic epithelial cell culture system from a mouse model for HNPCC and to isolate and characterize drug-resistant stem cells.

Experimental Models and Biomarkers

The Mlh1 [-/-]/Apc [-/-] Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cells is a mouse model for HNPCC, and the 5-fluoro-uracil resistant (5-FU-R) phenotype represents a model for the drug-resistant stem cells. Tumor spheroid formation, and the expression of CD44, CD133 and c-Myc represent stem cell markers.

Results

The HNPCC model exhibits aneuploidy, hyper-proliferation, accelerated cell cycle progression and downregulated cellular apoptosis. Long-term exposure to 5-FU selects for the drug-resistant phenotype. These resistant cells exhibit increased formation of tumor spheroids and upregulated expression of cancer stem cell markers CD44, CD133 and c-Myc.

Conclusion

In the present study, a stem cell model for HNPCC was validated and offered a novel experimental approach to test stem cell-targeted alternatives to drug-resistant therapy.

Keywords: hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer, drug resistant stem cells, cellular model

Introduction

In patients with genetic predisposition to early onset colon cancer the aberrant expression of selected genes presents the primary defects for tumor initiation. For example, germline mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor gene leads to the high-risk cancer precursor, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) syndrome, and the mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH3 and MSH6 alone or in concert with the APC mutation are the primary genetic defects that cause the development of hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC). Notably, the genetic defects in APC lead to chromosomal instability, whereas, those in DNA mismatch repair genes lead to microsatellite instability. Unstable microsatellites in the promoter regions of the APC, TGF-βRIII and BAX genes have a significant impact on the development of colon cancer in general and in particular on HNPCC.1–4

Germ line mutations in tumor suppressor genes and in DNA mismatch repair genes cause major genetic defects in patients with a genetic predisposition to colon cancers such as FAP and HNPCC. The HNPCC subtype is moderately prevalent, approximately 1% to 5%, in the general population.2,3 However, somatic mutations in these genes are also detected in sporadic colon cancer.3,4

Preclinical laboratory models of mice carrying germline mutations in the Apc gene and in DNA mismatch repair genes result in the accelerated formation of adenoma, predominantly in the small intestine.5–7 Cellular systems that express the relevant genetic defects in the appropriate target organ colon and display quantifiable carcinogenic risk offer novel mechanistic models for the study of genetic predisposition to colon carcinogenesis and to identify effective options for therapy-resistant disease.8–10

Conventional chemotherapy for colon cancer includes the DNA synthesis inhibitor 5-fluoro-uracil, the DNA intercalating agent oxaliplatin, and the topoisomerase I inhibitor irinotecan.11–13 In addition, the efficacy of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-inhibiting anti-inflammatory agents in colon cancer prevention/therapy is well documented.14,15 Long-term treatment with these agents may lead to systemic toxicity owing to their lack of specificity to tumor cells, acquired tumor resistance, and emergence of drug-resistant cancer stem cells that lead to therapy-resistant disease progression.16 Reliable cellular models for chemotherapy-resistant stem cells facilitate the identification of stem cell-targeted testable alternatives for therapy-resistant colon cancer. Of the cytotoxic agents used in chemotherapy, 5-fluoro-uracil (5-FU) has been a widely used component of multi-drug combinations in treatment of colon cancer.12 In the present study, 5-FU was used to select drug-resistant cells.

A colonic epithelial cell culture model that exhibits genetic defects relevant to clinical HNPCC has not been previously documented. Thus, the present research direction represents a novel experimental approach. The experiments in the present study were designed to i) characterize a colonic epithelial cell culture system developed from a mouse model genetically predisposed to HNPCC, and ii) to develop and characterize a 5-FU-resistant stem cell model.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Models

C57 COL

This cell line was isolated from the histologically normal descending colon of the C57BL/6J mouse. These cells express both the alleles for the Mlh1 and Apc genes. The genotype is designated as Mlh1 [+/+] /Apc [+/+].8 The C57 COL cell line is a model for normal colonic epithelial cells and provides a basis for comparison with the HNPCC model.

Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1

This cell line was established from a single anchorage-independent colony formed by the Mlh1/Apc1638N COL cell line.9 These clonally expanded cells lack the expression of both the alleles of the Mlh1 and Apc 1638N genes. The genotype is designated as Mlh1 [-/-]/Apc 1638N [-/-]. This cell line is a model for HNPCC.

Two cell lines were maintained in DME/F12 medium supplemented by 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY USA), 0.24 IU (10 µg/mL) insulin and 1 µM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck K Ga A). The culture medium also contained an antibiotic mixture (100 IU/mL penicillin-100µg/mL streptomycin, 50 µg/mL fungizone and 50 µg/mL gentamycin (all from Gibco)). The cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air: 5% CO2, and were sub-cultured through a 1:4 split when 80% confluent.

Test Agent

The DNA synthesis inhibitor 5-FU (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to select a drug-resistant phenotype. The stock solution of 10 mM 5-FU was prepared in phosphate buffered saline at a concentration of 10 mM, and was serially diluted in the culture medium to obtain micro molar concentrations used in the dose-response experiments.

Growth Assays

The population doubling times were calculated from viable cell counts at 24h, 48h, 72h and 96h after seeding of 1.0×105 cells using the Trypan blue dye exclusion kit (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck K Ga A). The difference in cell counts for unstained viable cells (Trypan blue negative) and stained non-viable cells (trypan blue positive) were used to calculate cell viability. The data were expressed as the means of the four time points. Saturation densities were determined from the number of viable cells at 7 days after seeding of 1.0×105 cells.

Growth inhibitory effects of 5-FU were monitored by determining the number of viable cells at 7 days after seeding of 1.0×105 cells. Minimally effective (IC25), half-maximal (IC50) and maximally cytostatic (IC90) inhibitory concentrations of 5-FU were extrapolated from the dose-response experiments. A viable cell count below the initial seeding density of 1.0×105 cells indicated that the concentration for 5-FU applied was toxic to the cells.

The anchorage- independent (AI) colony formation assay was used to determine the number of AI colonies formed at 14 days after seeding of 100 cells. Briefly, the cells were suspended in 0.33% agar and the cell suspension was over-laid on a basement matrix of 0.6% agar. The cultures were maintained at 37°C for 14 days and the AI colony counts were performed at 10x magnification.

Cell Cycle Progression

The cell cycle progression was monitored by flow cytometry using an EPICS 752 flow cytometer equipped with a 488 nm excitation and a 520 nm band pass filter (Coulter, Hialeah, FL, USA). Briefly, the cell suspension was fixed in ice cold 80% EtOH for 1 h, incubated with RNAse (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Freehold, NJ, USA) for 20 mins at 37°C and stained with 50 µg/mL propidium iodide (PI, Calbiochem Research Chemicals, La Jolla, CA, USA) in the dark overnight at 4°C. The fluorescent events from the PI-stained cells were gated on a forward versus side scatter, and the DNA analyses were performed using MPLUS software (Phoenix Flow Systems, San Diego, CA, USA). The flow cytometry-based analyses determined the distribution of cell population in each phase of the cell cycle (G1 [quiescent], S, G2/M [proliferative] and sub G0 [apoptotic]). The data were expressed as the cell population in the S+G2/M and sub G0 phases of the cell cycle, and as the S+G2/M: sub G0 ratio.

Drug Resistance

To isolate cells resistant to 5-FU, the Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cells were treated with the maximally cytostatic concentration of 0.5 µM (IC90) 5-FU. These cells were sub-cultured in the presence of 5-FU when approximately 90% confluent, and the actively proliferating cell population was maintained in the presence of 0.5 µM 5-FU for at least five passages. The 5-FU treated cells were used to characterize the resistant phenotype at the cellular and molecular levels.

Tumor Spheroid Formation Assay

To examine the formation of tumor spheroids, 5-FU- resistant Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cells were seeded at a density of 100 cells per well in ultralow adherence 6-well plates (Corning/Costar, Corning, NY, USA) in serum free DME/F12 medium supplemented with 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor, 10 ng/mL basal fibroblast growth factor (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck K Ga A), 1% B27, 10 ng/mL leukemia-inhibitory factor (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), 5µg/mL insulin, 1 ng/mL hydrocortisone, and 4µg/mL heparin sodium (all from Sigma-Aldrich). The cultures were maintained in the presence of 0.5 µM 5-FU at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air: 5% CO2 for a period of 14 days. The non-adherent spheroids formed by 14 days were counted at 10x magnification.

Immuno-Fluorescence Assay

The flow cytometry-based quantitative immuno-fluorescence assay was used to monitor the expression status of selected stem cell markers including CD44, CD133 and c-Myc. The 5-FU-resistant Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cells were stained with fluorescein isotho-cyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibodies CD44 (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, CA, USA), CD133 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) and c-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotecknology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) following the protocols provided by the vendors. The cellular uptake of the antibodies was confirmed by immuno-fluorescence microscopy (data not shown). The stained cells were quantified as the log mean fluorescence units (FU) per 104 fluorescent events that were normalized to that of FITC-IgG-stained cells.

Statistical Analyses

All experiments were performed in triplicate. The data were expressed as the mean ± SD, and were analyzed to determine the statistical significance of the difference between untreated control and treated experimental groups by Student’s t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s multiple comparison post-hoc test (α=0.05) and X2 test where appropriate, using Microsoft Excel 2013XLSTAT-Base software. P-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Experimental Models

The data presented in Table 1 quantify the growth characteristics of C57COL and Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cells. Relative to Mlh1 [+/+]/Apc [+/+] C57COL cells, Mlh1 [-/-] /Apc [-/-] Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cells exhibited a 50% decrease in the population doubling time (P=0.041), a 1.69-fold increase in saturation density (P=0.010), and an 18-fold increase in the AI colony number (P=0.001).

Table 1.

Growth Characteristics of Colonic Epithelial Cells

| Cell Line | Biomarker | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Population Doubling Timea (hr.) | Saturation Densitya (x105) | AI Coloniesb(number) | ||

| Mlh1 | Apc | ||||

| C57 COL | +/+ | +/+ | 34.0±3.9 | 7.8±0.2 | 0.8±0.5 |

| Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 | -/- | -/- | 17.0±1.6 | 21.0±1.2 | 15.2±1.4 |

| P | 0.041 | 0.010 | 0.001 | ||

| Relative to C57 COL | −50.0% | +1.69X | +18.0X | ||

Notes: aDetermined at 7 post-seeding of 1.0x105cells, mean ± SD, n=3 per treatment group. bDetermined at day 14 post-seeding of 100 cells, mean ±SD, n=18 per treatment group. Data analyzed by two-sample student’s t test.

Abbreviations: AI, anchorage independent; SD, standard deviation; X, fold change.

The data presented in Table 2 compares the extent of cellular proliferation and apoptosis in C57 COL and Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cell lines. Relative to C57 COL cells the Mlh1/1638NCOL-Cl1 cells exhibited a 26.8% increase in the cells that were in the proliferative phases of the cell cycle (S and G2/M) and a 34.9% decrease in the cells that were in the apoptotic (sub G0) phase of the cell cycle. The S+G2/M: sub G0 ratio was increased by 1.9-fold (P=0.010).

Table 2.

Cellular Proliferation and Apoptosis in Colonic Epithelial Cells

| Cell Line | Cell Cycle Phasea | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| S+G2/Mb (%) | Sub G0b (%) | S+G2/M: Sub G0b Ratio | |

| C57 COL | 24.6±3.3 | 4.3±0.1 | 5.7±0.3 |

| Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 | 31.2±2.4 | 2.8±0.1 | 11.1±1.2 |

| P | 0.049 | 0.010 | |

| Relative to C57 COL | +26.8% | −34.9% | +1.9X |

Notes: aDetermined at day 7 post-seeding of 1.0×105 cells using fluorescence assisted cell sorting. b Mean ± SD, n=3 per treatment group. Data analyzed by two-sample student’s t test.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; X, fold change.

Drug Resistance

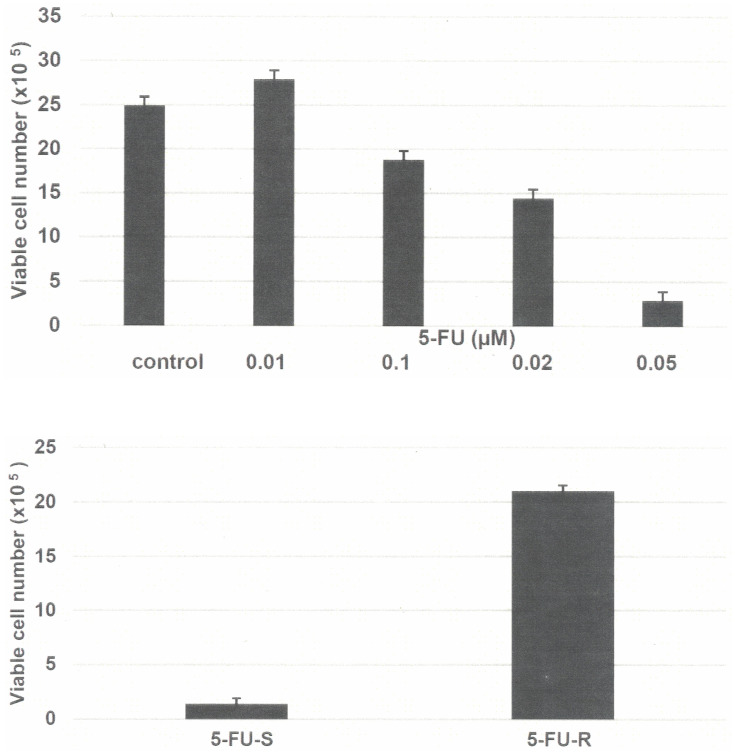

The data presented in Figure 1A demonstrate the growth inhibitory effect of 5-FU on Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cells. This growth inhibitory dose-response experiment identified the IC25 as 0.07 µM, the IC50 as 0.19 µM and the IC90 as 0.50 µM. Long-term exposure to 0.5 µM 5-FU was used to select the resistant phenotype. Initially, treatment with 0.5 µM 5-FU resulted in survival of approximately 10% of the treated cell population. This minor subpopulation exhibited gradual growth during the subsequent sub-culturing in the presence of 5-FU and yielded the 5-FU-R phenotype.

Figure 1.

(A) Growth inhibitory effect of 5-FU on Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cells. The number of viable cells number was determined 7 days after seeding of 1.0×105 cells. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD, n=3 per treatment group, and were analyzed by ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (α=0.05). 0.1 µM 5-FU P=0.047, 0.20 µM 5-FU P=0.038, 0.5 µM 5-FU P=0.010, relative to the untreated control. (B) Growth of 5-FU-R cells. Treatment with 0.5 µM 5-FU resulted in an increase in the number of viable cells. The number of viable cells was determined 7 days after seeding of 1.0×105 cells. The data are expressed as the mean ±SD, n=3 per treatment group, and were analyzed by two sample Student’s t-test. 5-FU-R P=0.001, relative to 5-FU-S.

Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluoro-uracil; ANOVA, analysis of variance; SD, standard deviation; 5-FU-R, 5-fluoro-uracil resistant; 5-FU-S, 5-fluoro-uracil sensitive.

The data presented in Figure 1B compare the growth of 5-FU sensitive (5-FU-S) and resistant (5-FU-R) cells in the presence of 0.5 µM 5-FU. Relative to 5-FU-S cells the 5-FU-R cells exhibited a 14-fold increase (P=0.001) in the number of viable cells.

Stem Cell Model

The data presented in Table 3 compares the expression of selected stem cell markers in 5-FU-S and 5-FU-R cells. Relative to the 5-FU-S cells, the 5-FU-R cells exhibited an 8.6-fold increase (P<0.001) in the number of tumor spheroids. In addition, in 5-FU-R cells, CD44 positive cells were increased by 5.1-fold (P<0.010), CD133 positive cells were increased by 5.2 fold (P<0.010), and c-Myc positive cells were increased by 2.9 fold (P<0.025), relative to the 5-FU-S cells, as evidenced by the log mean FU values.

Table 3.

Expression of Stem Cell Markers in Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 Cells

| Phenotype | 5-FU(µM) | Stem cell Marker Expression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS a | CD44 b | CD133 b | c-Myc b | ||

| 5-FU-S | 0.5 | 2.5±0.5 | 2.7±0.3 | 2.3±0.3 | 2.2±0.2 |

| 5-FU-R | 0.5 | 24.0±4.0 | 16.6±6.6 | 14.3±3.1 | 8.5±1.9 |

| X2 | 8.49 | ||||

| P | <0.010 | <0.010 | <0.010 | <0.025 | |

| Relative to 5-FU-S | +8.6X | +5.1X | +5.2X | +2.9X | |

Notes: aTS number determined at day 14 post-seeding. Mean ± SD, n=3 per treatment group. Data analyzed by X2 test. bCD44, CD133 and c-Myc determined at day 3 post-seeding and expressed as log mean FU ± SD, n=3 per treatment group. Data analyzed by two sample Student’s t test. Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluro-uracil; TS, tumor spheroid; CD, cluster of differentiation; C-Myc, cellular Myc; 5-FU-S, 5-FU-sensitive; 5-FU-R, 5-FU-resistant; X2, Chi square; SD, standard deviation; X, fold change.

Discussion

The cellular models developed for organ site epithelial cancers facilitate the direct investigations of target cancer cells. Most of the cellular models of colon cancer have been developed from human sporadic colon cancer samples. Human colon carcinoma derived cell lines in widespread use include HCT116 and SW480 which exhibit somatic mutations in the APC or MLH1 genes. In contrast, mouse colonic epithelial cell lines with germline mutations in the Apc and Mlh1 genes represent a novel experimental system that addresses the fundamental aspects of cancer initiation, promotion and progression, and facilitates the testing of alternatives for therapy resistant HNPCC. In this context, it is notable that colonic epithelial cell culture systems for germline mutant Apc 1638N mice and Apc 850 mutant mice have been established.8–10,17–19 These cell lines provide preclinical laboratory models for genetically predisposed colon cancer. In contrast, the development of cellular models for clinical HNPCC has not been reported. Thus, the data generated from the present experiments provide evidence for the development and characterization of a novel cellular model for HNPCC.

The experiments in the present study used the C57 COL cell line developed from the histologically normal descending colon of a C57/BL 6J mouse expressing the Mlh1 [+/+]/ Apc [+/+] genotype and the Mlh1/Apc COL-Cl1 cell line expressing the Mlh1[-/-]/Apc [-/-] genotype. The C57 COL cells exhibit a diploid phenotype, spontaneous immortalization, and absence of anchorage-independent (AI) colony formation in vitro and tumor formation in vivo.9,17–19 The Mlh1/1638NCOL-Cl1 cell line grows as a mixed population of diploid and aneuploid cells, and exhibits accelerated cell cycle progression and downregulated cellular apoptosis as evidenced by an increase in the S+G2/M: Sub G0 ratio and a decrease in the sub G0 phase. These hyper-proliferative cells also exhibit a high incidence of AI colony formation, the latter being an established surrogate biomarker for tumorigenic transformation.10,19 The data for Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cells are indicative of a loss of homeostatic growth control and a gain of quantifiable cancer risk in the present HNPCC model.

The DNA synthesis inhibitor 5-FU has been used in combination with folinic acid and oxaliplatin for the treatment of advanced metastatic colon cancer.12,13 5-FU is a prototypic cytotoxic agent that is commonly used as a component of a multi-drug combination in the conventional chemotherapy of colon cancer. In the present model of HNPCC, 5-FU was used to select the resistant phenotype. The 5-FU-R cells exhibited robust growth in the presence of the maximally cytostatic dose of 5-FU as evidenced by an increased number of viable cells relative to the 5-FU-S phenotype. These data demonstrate the effective selection and isolation of the drug-resistant phenotype from the parental 5-FU-sensitive Mlh1/1638N COL-Cl1 cells.

Long-term chemotherapy is associated with acquired drug resistance predominantly owing to the emergence of stem cell population that favor therapy-resistant disease progression. Cancer stem cells represent a minor subpopulation in the tumor that leads to therapy-resistance.16,20 In the experiment designed to characterize the stem cell phenotype, the expression of selected stem cell markers CD44, CD133 and c-Myc was monitored. Relative to the 5-FU-sensitive (5-FU-S) cells, the resistant cells exhibited substantially enhanced expression of the four markers as demonstrated by the increased number of TS and by increased antibody positivity for CD44, CD133 and c-Myc. Consistent with these data, it is notable that CD44, and CD133 are well-established markers in cancer stem cell models.21,22 These two markers are also documented to exhibit increased expression in response to 5-FU treatment in colon carcinoma derived cells.23–25 The transcription factor c-Myc is an established Apc target gene that is functional during the G1 to S phase transition of the cell cycle, and functions as an important factor in Wnt/β-catenin signaling for colonic epithelial stem cells.1 Furthermore, in conjunction with the transcription factors OCT-4, Klf-4 and SOX-2, c-Myc is essential for the induction and maintenance of the pluripotent stem cell phenotype derived from adult somatic cells.26,27

Drug-resistant models of cancer stem cells also represent a novel experimental approach to identify stem cell-targeting pharmacological as well as naturally occurring testable alternatives for therapy-resistant colon cancer.10 In this context, it is notable that several mechanistically distinct natural products including quercetin,28 sulforaphane,29,30 vitamin A derivative,31 benzyl isothio cyanate,32 carnosol33 and curcumin34 have documented efficacy in stem cell models developed from several organ site cancers. Collectively, this evidence has identified a potential future application for the present mechanistic approach to identify efficacious natural products as stem cell-targeting testable alternatives.

Investigations using cell culture models represent a cost-effective approach for the initial screening and prioritization of efficacious test agents. Promising agents can then be tested in subsequent in vivo experiments.

Conclusions

The colonic epithelial stem cell model for HNPCC exhibits hyper-proliferation and downregulation of apoptosis, indicating the loss of homeostatic growth control. The drug-resistant phenotype exhibits increased expression of cellular and molecular markers for stem cells. The present experimental approach should facilitate future research focused on identifying novel stem cell-targeting agents.

Acknowledgments

The present study represents a component of the research program entitled “Preclinical models for genetically predisposed early onset colon cancer”. This research program was supported by the US National Cancer Institute through contracts NCI MAA NO1 CN 75029-63, NO1 CN 85141, NO1 CN 05107 and NO1 CN 25111 (2000–2007).

Disclosure

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to the subject matter of the present study.

References

- 1.Fodde R, Smits R, Clevers H. APC, signal transduction and genetic instability in colon cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:55–67. doi: 10.1038/35094067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch HT, de la Chepelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:919–932. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rustgi A. The genetics of hereditary colon cancer. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2525–2538. doi: 10.1101/gad.1593107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajgopalan H, Novak MA, Vogelstein B, Lengauer C. The significance of unstable chromosomes in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:695–701. doi: 10.1038/nrc1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fodde R, Edelman W, Yang K, et al. A targeted chain termination mutation in the mouse Apc gene results in multiple intestinal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8969–8973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edelmann W, Yang K, Karaguchi M, et al. Tumorigenesis in Mlh1/Apc1638N mutant mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1301–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karaguchi M, Edelman W, Yang K, Lipkin M, Kucherlapati R, Brown AM. Tumor-associated Apc mutations in Mlh1-/- Apc 1638N mice reveal a mutational significance of Mlh1 deficiency. Oncogene. 2000;19:5755–5763. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katdare M, Kopelovich M, Telang N. Efficacy of chemo-preventive agents for growth inhibition of Apc [±] 1638N COL colonic epithelial cells. Int J Mol Med. 2002;10:427–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Telang N, Li G, Katdare M. Prevention of early-onset familial/hereditary colon cancer: new models and mechanistic biomarkers (Review). Int J Oncol. 2006;28:1523–1529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telang N. Anti-inflammatory drug resistance selects putative cancer stem cells in a cellular model for genetically predisposed colon cancer. Oncol Letts. 2018;15:642–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs C, Mitchell EP, Hoff PM. Irinotecan in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2006;32(7):491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg RM. Therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2006;11:981–987. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-9-981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Neal BH, Goldberg RM. Innovations in chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: an update of recent clinical trials. Oncologist. 2008;13:1074–1083. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta RA, Dubois RN. Colorectal cancer prevention and treatment by inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35094017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbruzzese JL, Lippman SM. The convergence of cancer prevention and therapy in early-phase clinical drug development. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holohan C, Van Schaeybroeck S, Longley DB, Johnston PG. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:714–726. doi: 10.1038/nrc3599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Telang N, Katdare M. Combinatorial chemo-prevention of carcinogenic risk in a model for familial colon cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007;17:909–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Telang N, Katdare M. Novel cell culture model for prevention of carcinogenic risk in familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:1017–1021. doi: 10.3892/or_00000318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Telang N, Katdare M. Preclinical in vitro models from genetically engineered mice for breast and colon cancer. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:1195–1201. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumor stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lobo NA, Shimono Y, Qian D, Clarke MF. The biology of cancer stem cells. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:675–699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel SA, Ndabahaliye A, Lim PK, Milton R, Rameshwar P. Challenges in the development of future treatments for breast cancer stem cells. Breast Cancer. 2010;2:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang H, Chen J-F, Pei L, Xie F-W, Liang H-J. Highly enriched CD133 (+) CD44 (+) stem-like cells with CD133(+)CD44High) metastatic subset in HCT116 colon cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2011;28:751–763. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9407-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C, Xie J, Guo J, Manning C, Gore JC, Guo N. Evaluation of CD44 and CD133 as cancer stem cell markers for colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:1301–1308. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou J-Y, Chen M, Ma L, Wang X, Chen Y-G, Liu S-L. Role of CD44 (high) /CD133 (high) HCT116 cells in the tumorigenesis of colon cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:7657–7666. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuli M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;1341:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou W, Kallifatidis G, Baumann B, et al. Dietary polyphenol quercetin targets pancreatic cancer stem cells. Int J Oncol. 2010;37:551–561. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kallifatidis G, Labsch S, Rausch V, et al. Sulforaphane increase drug-mediated cytotoxicity towards cancer stem-like cells of pancreas and prostate. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;19:188–195. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castro NP, Rangel MC, Merchant AS, MacKinnon G, Cittitta F. Sulforaphane suppresses the growth of triple negative breast cancer stem-like cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Prev Res. 2019;12:147–158. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-18-0241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen PH, Giraud J, Staedel C, et al. All-trans retinoic acid targets gastric cancer stem cells and inhibits patient derived gastric carcinoma tumor growth. Oncogene. 2016;35:5619–5628. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim SH, Sihgh SV. Role of Kruppel-like factor-4-p21 CIP−1 axis in breast cancer stem-like cell inhibition by benzyl isothio-cyanate. Cancer Prev Res. 2019;12:125–134. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-18-0393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Telang N. Targeting drug-resistant stem cells in a human epidermal growth factor receptror-2-enriched breast cancer model. World Acad Sci J. 2019;1:86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Telang N. Stem cell models for genetically predisposed colon cancer. Oncol Letts. 2020;20:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]