Abstract

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease associated with several comorbidities and reduced quality of life. In the past decades, highly effective targeted therapies have led to breakthroughs in the management of psoriasis, providing important insights into the pathogenesis. This article reviews the current concepts of the pathophysiological pathways and the recent progress in antipsoriatic therapeutics, highlighting key targets, signaling pathways and clinical effects in psoriasis.

Keywords: psoriasis, small molecules, signaling pathways, novel treatments, biologics

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease with regional prevalence varying between 0.14% and 1.99%.1 Psoriasis vulgaris is the most common type seen in approximately 90% of psoriasis cases. It is characterized by erythematous and scaly lesions that may affect any site of skin, but commonly affects predilection sites (extensor surfaces and scalp).2,3 Other less common types of psoriasis include: guttate psoriasis; inverse psoriasis; pustular psoriasis which may be generalized (generalized pustular psoriasis) or limited to palms and soles (palmoplantar pustulosis); and erythrodermic psoriasis, a rare, serious and widespread redness of the skin.3 Psoriasis is associated with comorbidities (eg, psoriatic arthritis, cardiovascular events, inflammatory bowel disease), psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation) and significantly reduced quality of life.4,5 Genetic, environmental (eg, skin trauma, infections) and behavioral factors (eg, smoking) contribute to the development of psoriasis.6,7 The pathogenesis of psoriasis is not fully elucidated yet, but most accepted concepts suggest an initiation and a maintenance phase of inflammation driven by an interplay between immune cells and keratinocytes mediated by cytokines.8,9 The mainstay of treatment is immunosuppression including phototherapy, topical and systemic treatment.2 In recent decades, the introduction of targeted therapy with biologics has led to major advancements in the management of psoriasis and further enhanced our understanding of the pathogenesis. This review provides the recent progress and insights from antipsoriatic therapeutics, highlighting key targets, signaling pathways and clinical effects in psoriasis vulgaris.

Pathogenesis

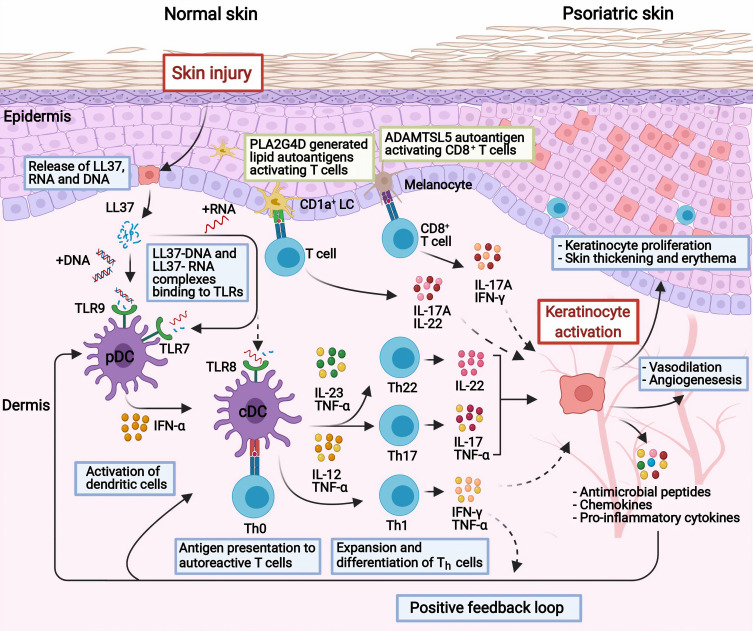

Psoriasis is a T cell mediated disease dependent on cross-talk between the innate and adaptive immune systems, in which dendritic cells (DCs) and keratinocytes have key roles.10 The psoriatic inflammation is characterized by an initiation phase, followed by chronic inflammation that is sustained by positive feedback loops. The exact immune events triggering the inflammatory cascade remain elusive. Autoantigens have been proposed as the pathomechanism of initiation. The most studied autoantigen is cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide, also known as LL-37, which is produced by immune cells and keratinocytes in response to skin injury (Figure 1).11,12 LL-37 forms complexes with self-DNA or RNA that activates plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) through Toll-like receptor-9 (TLR-9) and TLR-7, respectively.13,14 Subsequently, the pDCs produce interferon (IFN)-α that activates conventional DCs (cDCs). Moreover, RNA-LL37 may directly activate cDCs through TLR8.14 Hereafter, activated cDCs stimulate and promote the expansion of autoreactive T cells through antigen presentation and secretion of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)–12 and IL-23.15 The differentiation of naive T cells to T helper 17 cells (Th17) depends on the secretion of IL-23 together with TGFβ and IL-6, whereas the differentiation to Th1 depends on IL-12.15,16 The activated Th cells secrete cytokines; Th17 cells secrete IL-17, IL-22 and TNF-α, while Th1 cells secrete IFN-γ and TNF-α. These cytokines together stimulate the keratinocytes to proliferate and produce inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α), chemokines (eg, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5) and antimicrobial peptides (eg, S100A7/8/9, human β-defensin 2, LL-37), which recruit and further stimulate immune cells, amplifying the psoriatic inflammation.15,17,18 This positive feedback loop between T cells and keratinocytes drives the maintenance phase of the psoriatic inflammation.

Figure 1.

Current concepts of the pathogenesis in psoriasis. In response to skin injury, damaged keratinocytes release LL-37 which forms complexes with self-DNA/RNA. The complexes bind to TLRs and activate dendritic cells, which in turn promote the expansion and differentiation of autoreactive T cells through antigen presentation and secretion of cytokines. IL-23 promotes the differentiation of Th17 and Th22 cells, whereas IL-12 promotes Th1 cells. The activated Th22 and Th17 cells secrete TNF-α, IL-17 IL-22 that stimulate the keratinocytes to proliferate and produce inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides which further activate immune cells, enabling a positive feedback loop. Other concepts with autoantigens as triggers include; ADAMTSL5 in melanocytes which bind and activate autoreactive CD8+ T cells with subsequent release of IL-17 and IFN-γ; or PLA2G4D producing neolipid autoantigens expressed on CD1a+ dendritic cells, which upon presentation activate lipid-specific T cells secreting IL-17A and IL-22. Created with BioRender.com.

Abbreviations: ADAMTSL5, a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like 5; cDC, conventional dendritic cells; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; LC, Langerhans cell; LL37, cathelicidin; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; PLA2G4D, phospholipase A2 group IVD; Th, T helper cell; TLR, toll-like receptor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Other putative autoantigens include the melanocytic protein ADAMTS-like protein 5 (ADAMTSL5) which has been reported to be an autoantigen to epidermal autoreactive CD8+ T cells in patients with the risk gene HLA-C*06:02.19 Moreover, a cytoplasmic phospholipase A2, PLA2G4D (phospholipase A2 group IVD), has been hypothesized to generate non-peptide neolipid autoantigens for recognition on CD1a-expressing DCs to autoreactive T cells.20

Although the proposed models of initiation and pathogenesis (Figure 1) have been shown in in-vitro studies, the models remain hypothetical. Moreover, the models cannot be directly translated to clinical relevancy. For instance, therapies targeting IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-22 have failed to show clinical efficacy in patients with psoriasis.21–25

Treatment

Biologics

The introduction of targeted therapy with biologics has revolutionized the management of moderate to severe psoriasis as an effective and safe treatment. The proteinaceous nature of biologics allows high specificity of extracellular targets, but disadvantages include parenteral administration, high cost of manufacturing and immunogenicity.26 Currently, the four classes of biologics to treat psoriasis include TNF-α, IL-12/23, IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors. A summary of targeted therapies that are approved or under development for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Targeted Therapies for the Treatment of Psoriasis Vulgaris

| Drug Class | Agent | Target(s) | Stage of Development in Psoriasis | Administration | NCT Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNFα inhibitors | Adalimumab | TNFα | Approved | Sc | |

| Certolizumab | TNFα | Approved | Sc | ||

| Etanercept | TNFα | Approved | Sc | ||

| Infliximab | TNFα | Approved | Iv | ||

| Golimumab | TNFα | Sc | |||

| IL-17 inhibitors | Brodalumab | IL-17RA | Approved | Sc | |

| Ixekizumab | IL-17A | Approved | Sc | ||

| Secukinumab | IL-17A | Approved | Sc | ||

| Bimekizumab | IL-17A, IL-17F | Phase 3 | Sc | NCT03412747, NCT03536884, NCT03598790, NCT03766685 | |

| Netakimab (BCD-085) | IL-17A | Phase 3 (approved in Russia) | Sc | NCT03390101 | |

| ABY-035 | IL-17A, albumin | Phase 2 | Sc | NCT03591887 | |

| Sonelokinab (M1095) | IL-17A, IL-17F | Phase 2 | Sc | NCT03384745 | |

| Vunakizumab (SHR-1314) | IL-17A | Phase 3 | Sc | NCT04839016 | |

| IL-23 inhibitors | Guselkumab | IL 23p19 | Approved | Sc | |

| Risankizumab | IL 23p19 | Approved | Sc | ||

| Tildrakizumab | IL 23p19 | Approved | Sc | ||

| Mirikizumab | IL-23p19 | Phase 3 | Sc | NCT03482011, NCT03535194, NCT03556202 | |

| IL-12/23 inhibitor | Ustekinumab | IL-12/23p40 | Approved | Sc | |

| PDE4 inhibitors | Apremilast | PDE 4 | Approved | Oral | |

| Roflumilast | PDE 4 | Phase 3 | Topical/oral | NCT04549870, NCT04211363, NCT04211389, NCT04286607 | |

| Crisaborole (AN2728) | PDE 4 | Phase 2 | Topical | NCT01300052 | |

| Hemay005 | PDE 4 | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT04102241 | |

| JAK inhibitors | Deucravacitinib (BMS-986165) | TYK2 | Phase 3 | Oral | NCT04036435, NCT04772079, NCT03924427, NCT04167462, NCT03611751, NCT03624127 |

| Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) | JAK1, JAK3 | Phase 3 | Oral | ||

| Abrocitinib (PF-04965842) | JAK1 | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT02201524 | |

| Baricitinib (INCB028050) | JAK1, JAK2 | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT01490632 | |

| Brepocitinib (PF-06700841) | JAK1, TYK2 | Phase 2 | Oral/topical | NCT02969018, NCT03850483 | |

| Itacitinib (INCB039110) | JAK1 | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT01634087 | |

| Peficitinib (ASP015K) | JAK1, JAK2 JAK3, TYK2. | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT01096862 | |

| PF-06826647 | TYK2 | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT03895372 | |

| Ruxolitinib | JAK1, JAK2 | Phase 2 | Topical | NCT00617994 | |

| Solcitinib (GSK2586184) | JAK1 | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT01782664 | |

| RORγt inhibitor | AUR101 | RORγt | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT04207801 |

| BI 730357 | RORγt | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT03635099, NCT03835481 | |

| ESR-114 | RORγt | Phase 2 | Topical | NCT03630939 | |

| GSK-2981278 | RORγt | Phase 2 | Topical | NCT03004846 | |

| JTE-451 | RORγt | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT03832738 | |

| VTP-43742 | RORγt | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT02555709 | |

| STAT inhibitor | STA-21 | STAT3 | Phase 2 | Topical | NCT01047943 |

| S1PR1 antagonist | Ponesimod (ACT-128800) | S1PR1 | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT00852670, NCT01208090 |

| A3AR agonist | Piclidenoson (CF101) | A3AR | Phase 3 | Oral | NCT03168256 |

| AhR agonist | Tapinarof | AhR | Phase 3 | Topical | NCT04053387 |

| Fumeric acid esters | Fumaderm | Multiple | Approved in Germany | Oral | |

| Skilarence | Multiple | Approved in Europe | Oral | ||

| LAS41008 | Multiple | Phase 3 | Oral | NCT01726933 | |

| FP-187 | Multiple | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT01230138 | |

| PPC-06 | Multiple | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT03421197 | |

| XP23829 | Multiple | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT02173301 | |

| ROCK-2 inhibitor | Belumosudil (KD025) | ROCK2 | Phase 2 | Oral | NCT02317627, NCT02106195, NCT02852967 |

| HSP90 inhibitor | RGRN-305 (CUDC- 305) | HSP90 | Phase 1 | Oral | NCT03675542 |

Abbreviations: A3AR, A3 adenosine receptor; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; HSP90, heat shock protein 90; Iv, intravenous; JAK, janus kinase; PDE4, phosphodiesterase 4; ROCK, Rho-associated kinase; RORγt, retinoic acid-related orphan nuclear receptor gamma; Sc, subcutaneous.

TNF-α Inhibitors

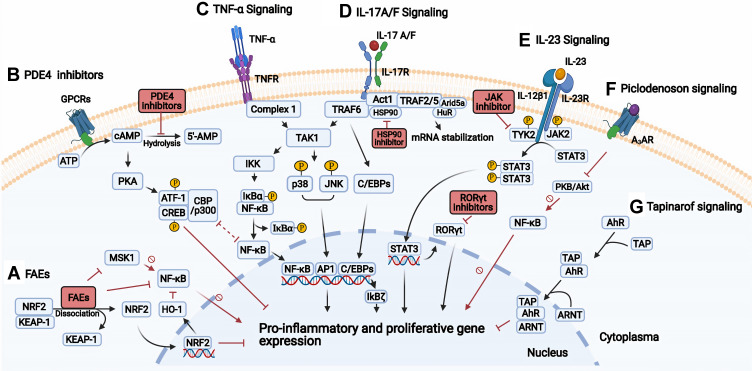

TNF-α is a major proinflammatory cytokine exerting effects on several cell types that are involved in the pathogenesis of multiple inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid disease, psoriatic arthritis and inflammatory bowel diseases.27 In the skin, TNF-α is produced by a variety of cells, such as immune cells (DCs, T cells, macrophages) and keratinocytes.17 The efficacy of targeting TNF-α in psoriasis is likely predominantly due to inhibition of the IL-23/17 pathway. In particular, TNF-α inhibitors reduce the release of IL-23 from cDCs, and decrease the synergistic effect of TNF-α on the IL-17 induced expression of psoriasis-related genes in keratinocytes.18 TNF-α is initially produced as a transmembrane protein that may reside on the cell surface or be cleaved by TNF-α Converting Enzyme to produce soluble TNF-α which may be released in the blood and exert its effects in remote tissues.28 Both soluble and transmembrane TNF-α exert biological activities by binding to two different receptors named TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) and TNFR2.29 Homotrimers of TNF-α bind to homotrimeric TNFRs to induce intracellular signaling through recruitment and assembly of different cytoplasmic complexes that result in distinct pathways and outcomes (eg, inflammation, apoptosis, survival, tissue regeneration).30 In the context of psoriatic inflammation, the signaling through complex I and activation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and activator protein (AP) 1 will be described in a simplified manner (Figure 2).31 Complex I recruits the transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ)-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) complex and inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase (IKK) complex. The TAK1 complex phosphorylates and activates the MAPKs p38 and c-JUN N-Terminal kinase (JNK), leading to activation of the transcription factor AP1. The IKK complex phosphorylates IκBα, leading to the release and activation of NF-κB.30–32 The activation of AP1 and NF-κB leads to proinflammatory regulation of gene transcription and proliferation of immune cells.30

Figure 2.

Signal transduction and targets in psoriasis. (A) Fumaric acid esters (FAEs) lead to the release of NRF2, which induce and repress the expression of cytoprotective and proinflammatory cytokine genes, respectively. Also, FAEs directly inhibit NF-κB, and indirectly through induced HO-1 or inhibition of MSK1. (B) PDE4 inhibition results in increased cAMP, activating PKA and subsequent phosphorylation of the transcription factors CREB and ATF-1, which lead to increased gene expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines, and inhibition of NF-κB due to competition of the coactivators (CBP or p300). (C) TNF-α binds to TNFR, then complex 1 assembles and TAK1 activates the IKK complex and MAPKs (JNK and p38). The IKK complex phosphorylates IκBα, leading to the release of NF-κB. JNK and p38 activate AP1. Both AP1 and NF-κB increase proinflammatory gene expression. (D) IL-17A/F stimulates the IL-17 receptor complex leading to the recruitment of Act1 followed by TRAFs. The TRAF6 activates the TAK1 pathway with activation of NF-κB and AP1. TRAF2/5 recruits RNA binding proteins (eg, HuR, Arid5a) that promote mRNA stabilization of proinflammatory transcripts. Inhibition of the chaperone HSP90 results in reduced function of Act1 (E) Upon binding of IL-23 to its receptor complex, TYK2 and JAK2 activate and phosphorylate STAT3, which dimerizes and promotes the expression of proinflammatory genes and RORγt. JAKi may disrupt the signaling by targeting TYK2/JAK2. The inhibition of RORγt results in decreased Th17 differentiation and response. (F) Upon binding of piclodenoson to A3AR, the activity of PKB/Akt is inhibited, leading to reduced NF-κB activity. (G) Tapinarof binds to AhR, the AhR-Tapinarof complex heterodimerizes with ARNT leading to downregulation of inflammatory cytokines and upregulation of skin barrier proteins. Created with BioRender.com.

Abbreviations: A3AR, A3 adenosine receptor; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; ARNT, AhR nuclear translocator; AP1, activator protein 1; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CBP, CREB-binding protein; C/EBPs, CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins; CREB, cAMP-response element-binding protein; FAE, fumaric acid ester; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; HSP90, heat shock protein 90; IκBζ, inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B zeta; IKK, inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase complex; JAKi, janus kinase inhibitor; JNK, c-JUN N-terminal kinase; Keap1, kelch-like ECH-associated protein; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinases; MSK1, mitogen- and stress-activated kinase 1; NrF2, nuclear factor E2-related factor 2; PKA, protein kinase A; PKB, protein kinase B; PDE, phosphodiesterase; ROR, retinoic acid-related orphan nuclear receptor; TAP, tapinarof; TAK1, transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ)-activated kinase 1; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFR1, TNF receptor; TRAF, TNF associated factors; TYK2, tyrosine kinase 2; S1PR1, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; STAT, signaling transducers and activators of transcription.

A total of five different TNF-α inhibitors are available for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, certolizumab); however, golimumab is not yet approved for psoriasis.33 Infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab are monoclonal antibodies, whereas etanercept is a fusion protein of the extracellular portion of TNFR-2 linked to a Fc portion of monoclonal antibody. Certolizumab is a Fab' fragment of a monoclonal antibody conjugated to polyethylene glycol.27,34 Although sharing the same target, different pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic features among the TNF-α inhibitors reflect clinical differences in terms of efficacy and adverse events.35 The short term (10–16 weeks) PASI75 (CI 95%) response varies among infliximab, 80.4% (76.5–84.0), certolizumab 71.1% (65.4–76.5), adalimumab 69.5% (66.0–72.6) and etanercept 40.1% (35.4–45.1).36 Most common adverse events (AEs) include nasopharyngitis, upper tract infections and injection site reactions. Compared to other biologics, the risk of reactivation of tuberculosis may be higher with TNF-α inhibitors.37 Although IL-23/IL-17 axis inhibitors seem superior in efficacy and safety to TNF-α inhibitors in psoriasis, the more widespread targeting of the immune system may confer advantages to psoriasis complicated with comorbidities, such as arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, hidradenitis suppurativa and uveitis.35,38

Interleukin 23 Inhibitors

IL-23 belongs to the IL-12 cytokine family including IL-12, IL-23, IL-27, IL-35, IL-39 and IL-Y, which share subunits and receptors.39,40 These heterodimeric cytokines consist of an α chain (p19, p28 or p35) and a β-chain (p40 or Ebi3). For instance, the p40 chain can pair to p35 or p19 to form IL-12 or IL-23, respectively.41 In psoriatic lesions, the expression of IL-23p19 and the p40 subunit shared by IL-12 and IL-23 are highly increased, whereas the IL-12p35 is not upregulated, suggesting that IL-23 has a key role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis compared to IL-12.42,43 As previously mentioned, IL-12 and IL-23 are secreted primarily by activated antigen presenting cells (eg, DCs) and induce Th1 and Th17 responses, respectively.44 Upon binding of secreted IL-23 to its heterodimeric receptor complex consisting of two transmembrane proteins (IL-12R β1 and IL-23R), the intracellular receptor-associated tyrosine kinases TYK2 and JAK2 become activated and phosphorylate the receptor complex, creating a docking site and recruitment of predominantly signaling transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) 3, and to a lesser extent STAT1, STAT2, and STAT4 (Figure 2). These transcription factors become phosphorylated, dimerized and translocated to the nucleus to regulate the expression of numerous genes.45,46 Of interest, STAT3 promotes the expression of another transcription factor RORγt.47 STAT3 and RORγt, induce the expression of genes, including IL17A, IL17F, IL22, IL23R, which are pivotal for the Th17 response and development of psoriasis.48

To date, four IL-23 inhibitors are approved to treat moderate to severe psoriasis (ustekinumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab).49 Ustekinumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting the p40 subunit shared by IL-12 and IL-23, thus inhibiting both IL-12 and IL-23 signaling. Guselkumab, tildrakizumab and risankizumab are monoclonal antibodies specifically inhibiting IL-23 signaling by targeting IL-23p19.50 A fourth IL-23p19 monoclonal antibody, mirikizumab is being tested in Phase 3 clinical trials (NCT03482011, NCT03535194, NCT03556202). The IL-23 inhibitors represent effective options in treatment of psoriasis with infrequent dosing and satisfactory short term (week 10–16) PASI75 (CI 95%) response rates; risankizumab 89.2% (86.9–91.3), guselkumab 86.8% (83.8–89.4), mirikizumab 82.5% (78.9–86.1), tildrakizumab 64.9 (59.4–70.3), ustekinumab 69.7 (66.3–73.1).36,51 The clinical response rates of ustekinumab and tildrakizumab seem to be inferior to the other IL-23 inhibitors.36,50,52 This could be explained by lower affinity (tildrakizumab) or mode of inhibition (ustekinumab).53 Moreover, IL-12 signaling may confer protective effects reducing skin inflammation; hence, blockade of IL-12 signaling by ustekinumab may be counterproductive resulting in less efficacy.54 The safety and tolerability of IL-23 inhibitors seem to be benign with adverse events including nasopharyngitis, upper tract respiratory tract infections, headache, and injection site reactions being the most commonly reported.50

Interleukin 17 Inhibitors

The IL-17 family consists of six different subunits (IL-17A to IL-17F) that form functional IL-17 as homodimers of each subtype. As an exception, IL-17A and IL-17F can form heterodimers. Similar to IL-23 receptors, the IL-17 cytokines bind to heterodimeric receptor complexes composed of two transmembrane subunits.55 The IL-17A and IL-17F cytokines are produced by several cells, especially Th17 and Tc17 cells, exerting their effect on keratinocytes leading to proliferation and production of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and antimicrobial peptides, which perpetuate the inflammatory environment leading to psoriatic lesions.15,17 IL-17A homodimers, IL-17F homodimers or IL-17A/F heterodimers transmit through the same receptor complex composed of IL-17RA and IL-17RC subunits.55 Upon ligand binding, the intracellular domain of the receptor complex recruits Act1, an adaptor protein, which binds different TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) to initiate downstream pathways (Figure 2). Similar to TNF-α signaling, IL-17 signaling results in the activation of AP1 and NF-κB transcription factors leading to the expression of proinflammatory target genes. Upon binding to Act1, TRAF6 recruits TGF-β activated kinase 1 (TAK1), which activates IKK complex and MAPKs (JNK and p38). The IKK complex phosphorylates IκBα, leading to the release and activation of NF-κB. MAPKs phosphorylate and activate AP1.56,57 Moreover, IL-17 signaling promotes post-transcriptional mRNA stabilization of proinflammatory transcripts through Act1 or RNA binding proteins (eg, HuR, Arid5a) recruited by TRAF2 and TRAF5 (Figure 2).57,58 Importantly, IL-17-signaling results in enhanced gene expression of additional transcription factors such as a IκBζ and CCAAT/enhancer bindings proteins (C/EBPs). These additional transcription factors promote expression of IL-17 target genes, providing a feed-forward mechanism potentiating inflammation.57 IκBζ (encoded by NFKBIZ) has been proposed to play a key role in mediating the effects of IL-17A and IL-17F.59–61

The class of IL-17 inhibitors has three monoclonal antibodies approved for the treatment of psoriasis; Secukinumab and ixekizumab target IL-17A preventing the signaling of IL-17A homodimers and 17A-F heterodimers; brodalumab targets the receptor IL-17RA which is involved in different receptor complexes and thus blocks the signaling of IL-17A, IL-17C, IL-17E and IL-17F.49,62 The efficacy and rapid response of IL-17 inhibitors have been demonstrated with good short term (week 10–16) PASI75 response rates; brodalumab 88.7% (86.5–90.8), ixekizumab, 88.8% (86.5–90.9) and secukinumab 83.1% (80.2–85.7).36 Recently, bimekizumab, an antibody targeting both IL-17A and IL-17F, has completed phase 3 trials.63,64 The clinical response to bimekizumab was rapid and substantial with 77% of subjects achieving PASI75 at week 4 and 91% of subjects achieving PASI90 at week 12.63 Whether the dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F (bimekizumab) is superior to inhibition of IL-17A (secukinumab) is currently being investigated in a head-to-head comparison in a phase 3 clinical trial (NCT03536884). Additionally, other IL-17 inhibitors are being tested in clinical trials including netakimab (NCT03390101), sonelokinab (NCT03384745), ABY-035 (NCT03591887) and vunakizumab (NCT04839016) (Table 1). IL-17 inhibitors are generally well tolerated, although they are associated with higher incidence of mucocutaneous candidiasis and exacerbation of IBD.65,66

The targeted therapies with biologics have proved to be highly effective, providing new insights into the pathogenesis and key signaling pathways, which can be targeted by small molecules.

Small Molecules

Small molecules are organic small molecules typically with a molecular weight <700 Da, which offers several advantages compared to biologics.26 Small molecules can be formulated for oral or topical administration, diffuse into cells and target intracellular signaling pathways, and have typically lower manufacturing costs. However, disadvantages of small molecules include lower target selectivity with off-target effects and currently lower efficacy in psoriasis compared to biologics.67 Classes of small molecules encompass phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors, janus kinase inhibitors, fumaric acid esters, RORγt inhibitors, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 antagonist, aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, A3 adenosine receptor agonist and heat shock protein 90 inhibitors.

Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors

Phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) is one of the major PDEs expressed in immune cells (DCs, T cells, macrophages, and monocytes) and keratinocytes, and is responsible for the hydrolysis of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), a second messenger involved in mediating immunoregulatory effects (Figure 2).68 The production of cAMP is regulated through hormonal stimulation of G-coupled receptors, which activates membrane-associated adenylyl cyclases converting ATP to cAMP.68 PDE4 inhibitors are small molecules targeting PDE4 leading to increased cytosolic cAMP, which activates protein kinase A (PKA), exchange protein 1/2 activated by cAMP and cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Through phosphorylation, PKA activates transcriptional factors including cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB), cAMP-responsive modulator (CREM) and ATF1, which leads to increased expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines.69,70 Also, the activation of these transcription factors leads to the recruitment of the coactivators CREB binding protein (CBP) or the homologous protein p300, leading to inhibition of the proinflammatory transcription factor NF-κB through competition for the coactivators (CBP or p300).69–71

Phase II, III and IV studies with apremilast (PDE4 inhibitor) have shown significant reductions in plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22 and TNF-α.72,73 In keratinocytes stimulated with IL-17, apremilast reduced the expression of genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines and alarmins.74 Taken together, PDE4 regulates the expression and signaling of key cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

Apremilast is the only PDE4 inhibitor approved for the treatment of psoriasis and PsA,75 while others (eg, roflumilast and crisaborole) are being studied. The short term (10–16 weeks) and long term (44–60 weeks) PASI75 response to apremilast were 30.8% and 43.2%, respectively.36 The main AEs were mild to moderate nausea, diarrhea, headache, upper tract infections and nasopharyngitis.76–78 Roflumilast is reportedly 25–300 times more potent than apremilast and crisaborole while maintaining a favorable safety profile, and roflumilast is approved for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.79,80 Oral roflumilast is currently being investigated in a Phase 2 trial (NCT04549870). Topical roflumilast has completed phase 3 trials, but the results have not been published yet (NCT04211363, NCT04211389). In a phase 2 trial, topical roflumilast demonstrated a 34% (95% CI 26–43) PASI75 response at week 12.81

Janus Kinase Inhibitors

Many of the key pathogenic cytokines in psoriasis (eg, IFNs, IL-6, IL-22, IL-23) bind to their receptor and transmit the intracellular signaling through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway.82 The janus kinases family includes four different intracellular tyrosine kinases (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 and TYK2), and the STAT family includes seven different STAT proteins (STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5a, STAT5b, STAT6).83 Upon cytokine binding, the JAKs become activated, autophosphorylated and phosphorylate the receptor leading to binding of STAT proteins (Figure 2).83 Subsequently, JAKs phosphorylate these transcription factors (STAT1-STAT6), which dimerize and migrate to the nucleus to regulate transcription and gene expression.84 In addition to JAK2/TYK2 and STAT3 as part of the IL-23 signaling, other JAK and STAT proteins may have important roles in psoriasis.85 For example, IFN-α involved in the activation of cDCs signals through JAK1/TYK2-dependent activation of STAT1/STAT2.15,86 Also, STAT3 is implicated in the pathological response of keratinocytes to cytokines, including keratinocyte proliferation and production of antimicrobial peptides secondary to activation of JAK1/TYK2 and STAT3 induced by IL-22 signaling.82,87 Although TNF-α and IL-17A do not directly activate the JAK-STAT pathway, the inhibition of JAK-STAT may indirectly suppress the effects of these cytokines by inhibition of other JAK/STAT dependent cytokines involved in the vicious cytokine circuits known to drive the disease pathogenesis in psoriasis (eg, inhibition of IL-23 acting upstream to IL-17).88

To date, JAK inhibitors (JAKi) are under investigation for psoriasis, while selective STAT inhibition remains a pharmacological challenge.48 Currently, two JAKi are or have been in phase 3 trials for psoriasis, tofacitinib (JAK1/JAK3 inhibitor) and deucravacitinib (TYK2 inhibitor), though the results from the phase 3 trials for deucravacitinib have not yet been published (NCT03624127). None of the JAKi are approved for the treatment of psoriasis; however, tofacitinib is approved for PsA.49 Several JAKi have undergone phase 2 clinical trials, including inhibitors of JAK1/JAK2 (baricitinib, ruxolitinib), JAK1 (itacitinib, solcitinib, abrocitinib), TYK2 (PF-06826647), JAK1/TYK2 (brepocitinib) and pan-JAK (peficitinib), but it remains elusive whether or not these programs will proceed in to phase 3 clinical testing. The short-term PASI75 response was 59% at week 16 with tofacitinib based on two phase 3 clinical trials89 and 75% at week 12 with deucravacitinib based on phase 2 clinical trial data.90 The safety is acceptable; however, tofacitinib has been associated with thrombosis, laboratory abnormalities (dyslipidemia, anemia, neutropenia, elevation of liver enzymes creatinine),91 and recently serious heart-related problems and cancer.92 The selectivity of TYK2 inhibitors may offer a better benefit-risk profile. The phase 2 trial with deucravacitinib found no changes in laboratory parameters.90 Nevertheless, the ongoing trials with TYK2 inhibitors (phase 3 trials with deucravacitinib and phase 2 trial with PF-06826647) will clarify whether these drugs will be an effective and safe therapeutic option (NCT04036435, NCT04772079, NCT03924427, NCT04167462, NCT03611751, NCT03624127, NCT03895372). Interestingly, JAKi can be developed as topical formulations, providing another therapeutic option. Tofacitinib and ruxolitinib have shown modest improvements with a favorable safety profile,93 and topical brepocitinib is being evaluated in an ongoing phase 2 trial (NCT03850483).

Fumaric Acid Esters

Fumaric acid esters (FAEs) are lipophilic ester derivatives of fumaric acid that possess anti-inflammatory effects. The molecular mechanism of action is complex and not completely understood. It seems that the main molecular mechanisms involve the activation of NrF2 (nuclear factor E2-related factor 2) and inhibition of NF-κB (Figure 2).94–96 The binding of FAEs to cysteine residues of Keap1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1) induces a conformational change and release of the transcription factor NrF2.94 Subsequently, NrF2 migrates to the nucleus to promote the transcription of cytoprotective genes and represses the transcription of proinflammatory cytokine genes.97,98 The transcription factor NF-κB may be inhibited by several direct or indirect mechanisms leading to anti-inflammatory effects. For instance, FAEs can directly inhibit the nuclear translocation and DNA-binding of NF-κB by covalent modification of the p65 subunit of NF-κB.99 Moreover, mitogen stress-activated kinase 1 (MSK1) is inhibited by FAEs, reducing the phosphorylation of NF-κBp65 and thereby inhibiting the transcriptional activity of NF-κB.100,101 Also, NrF2 signaling may inhibit NF-κB; Heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1), a protein inducible by NrF2, inhibits NF-κB;102 and the competition with NrF2 over the shared transcriptional coactivator p300 leads to inhibition of NF-κB.103 Finally, other molecular mechanisms may involve the modulation of intracellular glutathione levels, other transcription factors (eg, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α), the JAK/STAT pathway, and agonism of the hydroxy‑carboxylic acid receptor 2.94

Different oral FAEs have been investigated or approved for psoriasis including dimethyl fumarates (skilarence, LAS41008, FP-187), tepilamide fumarate (PPC-06) and a combination of dimethyl fumarate and salts of monomethyl fumarate (fumaderm). In Germany, fumaderm was approved for the treatment of psoriasis in 1994, and skilarence was approved in 2017 by the European Medicines Agency.104 In a phase 3 clinical trial, the PASI75 response at week 16 was achieved in 37.5% of subjects with dimethyl fumarate (LAS41008) and 40.3% with a combination of dimethyl fumarate and salts of monomethyl fumarate (fumaderm).105 Based on recent results from a phase 2 clinical trial, tepilamide fumarate (PPC-06) led to a 47.2% PASI75 response at week 24.106 The AEs of FAEs are mostly mild and include gastrointestinal disorders, flushing, leukopenia and lymphopenia.104

RORγt Inhibitors

The retinoic acid-related orphan nuclear receptors, RORα, -β, and -γ, are ligand-dependent transcription factors.107 RORγt (an isoform of RORγ) is implicated in Th17 cell differentiation and effector function. IL-23 signaling activates STAT3, inducing the expression of RORγt which prompts the Th17 response by promoting the expression of IL17A, IL17F, IL22, IL23R.47 Thus, inhibition of RORγ is an attractive pharmacological target to hamper the Th17 response. Moreover, the inhibition of RORγt and thereby Th17 differentiation drives the differentiation of naïve T cells to regulatory T cells, which secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-10) and inhibit immune response.16

Several RORγt inhibitors are active or have completed phase 2 clinical trials in psoriasis including VTP-43742, JTE-451, AUR101 and BI 730357. VTP-43742 demonstrated in a placebo-controlled trial a 30% reduction in PASI at week 4, but the trial program was discontinued due to liver toxicity, and VTP-43742 was replaced by a new improved molecule VTP-45489.108,109 The results for JTE-451 have not yet been published (NCT03832738), while AUR101 and BI 730357 are being tested in ongoing phase 2 trials in psoriasis (NCT04207801 NCT03635099, NCT03835481).

Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 1 Antagonist

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a lipid mediator binding to G-protein coupled receptors (S1PR1-5), which are involved in lymphocyte trafficking.110 Ponesimod, an oral S1PR1 antagonist, induces internalization of S1PR1 and thereby preventing the migration of lymphocytes from secondary lymphoid tissue to the circulation and infiltration in the skin.111 In a phase 2 trial in psoriasis, PASI75 was achieved in 48.1% of subjects at week 16 and 77.5% of subjects at week 28.111 Ponesimod has been associated with increased risk of infections, liver transaminase elevation, hypertension, dyspnea, macular edema, cutaneous malignancies, fetal risk, bradyarrhythmia and atrioventricular conduction delays.112 Although ponesimod was recently approved by the FDA to treat multiple sclerosis, it is currently not being further investigated in psoriasis.113,114

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a cytosolic ligand-dependent transcription factor found in a variety of cells (eg, immune cells and keratinocytes) that can be activated by a wide range of ligands (eg, endogenous, dietary, environmental).115 Upon ligand binding, the AhR-ligand complex translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, heterodimerizes with AhR nuclear translocator (ARNT) and regulates transcription of target genes (Figure 2).115,116 Tapinarof (AhR agonist) mediates AhR signaling that results in downregulation of inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-17), reduction of oxidative stress and increased expression of skin barrier proteins (eg, filaggrin, loricrin), providing therapeutic benefits in psoriasis.115,117 Two phase 3 trials with topical topinarof have shown 36.1% and 47.6% PASI75 response rates at week 12.118 Most AEs were mild to moderate and included folliculitis, contact dermatitis, headache and upper respiratory tract infections.118,119

A3 Adenosine Receptor Agonist

A3 Adenosine receptor (A3AR) is a Gi protein-coupled cell surface receptor, which mediates anti-inflammatory effects.120 Piclidenoson, an oral A3AR agonist, inhibits keratinocyte proliferation by downregulating the proinflammatory NF-κB signaling pathway (Figure 2), leading to anti-inflammatory effects and decreasing expression levels of TNF- α, IL-17 and IL-23.120,121 In a phase 2 trial, systemic treatment with piclidenoson demonstrated a 35.5% PASI75 response rate at week 32 and was well tolerated.122 It is currently being tested in a phase 3 trial (NCT03168256).

Heat Shock Protein 90

Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) is a chaperone protein whose major role is folding, stabilization and activation of client proteins including transcriptional factors and intracellular signaling molecules mediating inflammation (eg, Act1 involved in IL-17 signaling) (Figure 2).123,124 Hence, inhibition of HSP90 may be a potential therapeutic strategy for psoriasis. The HSP90 inhibitor RGRN-305 has shown promising antipsoriatic effects in a xenograft mouse model, and in vitro it inhibited the expression of proinflammatory genes such as TNFα, IL23A and NFKBIZ (encoding IκBζ) in cultured normal human keratinocytes.125,126 A Phase 1 clinical trial with RGRN-305 in patients with psoriasis is currently ongoing (NCT03675542).

Conclusion

The recent progress of highly effective biological therapies targeting extracellular cytokines has provided new insights into the pathogenesis and key signaling pathways in psoriasis. These new insights have enabled novel therapeutic strategies with small molecules targeting intracellular molecules and pathways. Although the efficacy of current small molecules seems to be inferior to the newer biologics, small molecules offer advantages such as oral administration, lower manufacturing costs and absence of immunogenicity. Further basic and clinical research is required to determine the future roles of the novel small-molecule therapeutics in the management of psoriasis.

Funding Statement

There is no funding to report.

Abbreviations

A3AR, A3 adenosine receptor; AD, adverse event; ADAMTSL5, a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like 5; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; AP1, activator protein 1; CBP, coactivators CREB binding protein; cDC, conventional dendritic cell; C/EBPs, CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins; CREB, cAMP-response element-binding protein: CREM, cAMP-responsive modulator; DC, dendritic cells; FAE, fumaric acid ester; HSP90, heat shock protein 90; IFN, interferon; IκBζ, inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B zeta; IKK, inhibitor of κB (IκB) kinase; IL, interleukin; JAK, janus kinase; JNK, c-JUN N-terminal kinase; Keap1, kelch-like ECH-associated protein; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinases; MSK1, mitogen- and stress-activated kinase 1, NFκB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NrF2, nuclear factor E2-related factor 2; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; PKA, protein kinase A; PLA2G4D, phospholipase A2 group IVD; PDE, phosphodiesterase; ROR, retinoic acid-related orphan nuclear receptor; TAK1, transforming growth factor-beta (TGFβ)-activated kinase 1; Th, T helper cells; TLR, Toll-like receptor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFR1, TNF receptor; TRAF, TNF associated factors; TYK2, tyrosine kinase 2; S1PR1, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1; STAT, signaling transducers and activators of transcription.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted, gave final approval for the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

LI has served as a consultant and/or paid speaker for and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by: AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Centocor, Eli Lilly, Janssen Cilag, Kyowa, Leo Pharma, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Regranion, Samsung, Union Therapeutics UCB. HBA has received research grants from Regranion and Kgl. Hofbuntmager Aage Bangs Fond. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Parisi R, Iskandar IYK, Kontopantelis E, Augustin M, Griffiths CEM, Ashcroft DM. National, regional, and worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis: systematic analysis and modelling study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1590. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1945–1960. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61909-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(3 Pt 1):401–407. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70112-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsoi LC, Stuart PE, Tian C, et al. Large scale meta-analysis characterizes genetic architecture for common psoriasis associated variants. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15382. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamiya K, Kishimoto M, Sugai J, Komine M, Ohtsuki M. Risk factors for the development of psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18):4347. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greb JE, Goldminz AM, Elder JT, et al. Psoriasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16082. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowes MA, Suárez-Fariñas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of psoriasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:227–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J, Krueger JG. The immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2014.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lande R, Botti E, Jandus C, et al. The antimicrobial peptide LL37 is a T-cell autoantigen in psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5621. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ten Bergen LL, Petrovic A, Aarebrot AK, Appel S. Current knowledge on autoantigens and autoantibodies in psoriasis. Scand J Immunol. 2020;92(4):e12945. doi: 10.1111/sji.12945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature. 2007;449(7162):564–569. doi: 10.1038/nature06116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganguly D, Chamilos G, Lande R, et al. Self-RNA-antimicrobial peptide complexes activate human dendritic cells through TLR7 and TLR8. J Exp Med. 2009;206(9):1983–1994. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alwan W, Nestle FO. Pathogenesis and treatment of psoriasis: exploiting pathophysiological pathways for precision medicine. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33(5 Suppl 93):S2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee GR. The balance of Th17 versus Treg cells in autoimmunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3). doi: 10.3390/ijms19030730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkes JE, Chan TC, Krueger JG. Psoriasis pathogenesis and the development of novel targeted immune therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(3):645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawkes JE, Yan BY, Chan TC, Krueger JG. Discovery of the IL-23/IL-17 signaling pathway and the treatment of psoriasis. J Immunol. 2018;201(6):1605–1613. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arakawa A, Siewert K, Stöhr J, et al. Melanocyte antigen triggers autoimmunity in human psoriasis. J Exp Med. 2015;212(13):2203–2212. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung KL, Jarrett R, Subramaniam S, et al. Psoriatic T cells recognize neolipid antigens generated by mast cell phospholipase delivered by exosomes and presented by CD1a. J Exp Med. 2016;213(11):2399–2412. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harden JL, Johnson-Huang LM, Chamian MF, et al. Humanized anti-IFN-γ (HuZAF) in the treatment of psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(2):553–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bissonnette R, Papp K, Maari C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase I study of MEDI-545, an anti-interferon-alfa monoclonal antibody, in subjects with chronic psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(3):427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfizer. Study evaluating single dose of ILV-095 in psoriasis subjects NCT01010542. clinicaltrials.gov. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01010542. Accessed June30, 2021.

- 24.Pfizer. Study evaluating the safety and tolerability of ILV-094 in subjects with psoriasis NCT00563524. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00563524?term=ILV-094&draw=2&rank=2. Accessed June30, 2021.

- 25.Tsai Y-C, Tsai T-F. Anti-interleukin and interleukin therapies for psoriasis: current evidence and clinical usefulness. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2017;9(11):277–294. doi: 10.1177/1759720X17735756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mócsai A, Kovács L, Gergely P. What is the future of targeted therapy in rheumatology: biologics or small molecules? BMC Med. 2014;12:43. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitoma H, Horiuchi T, Tsukamoto H, Ueda N. Molecular mechanisms of action of anti-TNF-α agents - Comparison among therapeutic TNF-α antagonists. Cytokine. 2018;101:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horiuchi T, Mitoma H, Harashima S, Tsukamoto H, Shimoda T. Transmembrane TNF-alpha: structure, function and interaction with anti-TNF agents. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(7):1215–1228. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Locksley RM, Killeen N, Lenardo MJ. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies: integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104(4):487–501. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00237-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalliolias GD, Ivashkiv LB. TNF biology, pathogenic mechanisms and emerging therapeutic strategies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(1):49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holbrook J, Lara-Reyna S, Jarosz-Griffiths H, McDermott M. Tumour necrosis factor signalling in health and disease. F1000Res. 2019;8:111. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.17023.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenner D, Blaser H, Mak TW. Regulation of tumour necrosis factor signalling: live or let die. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(6):362–374. doi: 10.1038/nri3834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.FDA. FDA approved drugs. Biologic License Application (BLA): 125289. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=125289. Accessed March17, 2021.

- 34.Fundation NP. Biologics; [updated October 10, 2020]. Available from: https://www.psoriasis.org/biologics/. Accessed March17, 2021.

- 35.Campanati A, Paolinelli M, Diotallevi F, Martina E, Molinelli E, Offidani A. Pharmacodynamics OF TNF α inhibitors for the treatment of psoriasis. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(11):913–925. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2019.1681969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armstrong AW, Puig L, Joshi A, et al. Comparison of biologics and oral treatments for plaque psoriasis: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(3):258–269. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nogueira M, Warren RB, Torres T. Risk of tuberculosis reactivation with interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-23 inhibitors in psoriasis - time for a paradigm change. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(4):824–834. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rønholt K, Iversen L. Old and new biological therapies for psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(11):2297. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mirlekar B, Pylayeva-Gupta Y. IL-12 family cytokines in cancer and immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(2):167. doi: 10.3390/cancers13020167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flores RR, Kim E, Zhou L, et al. IL-Y, a synthetic member of the IL-12 cytokine family, suppresses the development of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(11):3114–3125. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vignali DA, Kuchroo VK. IL-12 family cytokines: immunological playmakers. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(8):722–728. doi: 10.1038/ni.2366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee E, Trepicchio WL, Oestreicher JL, et al. Increased expression of interleukin 23 p19 and p40 in lesional skin of patients with psoriasis vulgaris. J Exp Med. 2004;199(1):125–130. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen X, Tan Z, Yue Q, Liu H, Liu Z, Li J. The expression of interleukin-23 (p19/p40) and interleukin-12 (p35/p40) in psoriasis skin. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2006;26(6):750–752. doi: 10.1007/s11596-006-0635-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chyuan I-T, Lai J-H. New insights into the IL-12 and IL-23: from a molecular basis to clinical application in immune-mediated inflammation and cancers. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;175:113928. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tait Wojno ED, Hunter CA, Stumhofer JS. The Immunobiology of the Interleukin-12 family: room for discovery. Immunity. 2019;50(4):851–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Floss DM, Schröder J, Franke M, Scheller J. Insights into IL-23 biology: from structure to function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015;26(5):569–578. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang L, Yang X, Liang Y, Xie H, Dai Z, Zheng G. Transcription factor retinoid-related orphan receptor γt: a promising target for the treatment of psoriasis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1210. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghoreschi K, Balato A, Enerbäck C, Sabat R. Therapeutics targeting the IL-23 and IL-17 pathway in psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397(10275):754–766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00184-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.FDA. Drugs@FDA: FDA- approved drugs. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/. Accessed March21, 2021.

- 50.Yang K, Oak ASW, Elewski BE. Use of IL-23 inhibitors for the treatment of plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(2):173–192. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00578-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Company ELa. A study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of mirikizumab (LY3074828) in participants with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (OASIS-1); 2020. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT03482011?term=mirikizumab&cond=Psoriasis&draw=2&rank=1. Accessed March21, 2021.

- 52.Sawyer LM, Malottki K, Sabry-Grant C, et al. Assessing the relative efficacy of interleukin-17 and interleukin-23 targeted treatments for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of PASI response. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0220868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou L, Wang Y, Wan Q, et al. 394 IL-23 antibodies in psoriasis – a non-clinical perspective. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(9, Supplement):S282. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.07.396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kulig P, Musiol S, Freiberger SN, et al. IL-12 protects from psoriasiform skin inflammation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13466. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brembilla NC, Senra L, Boehncke WH. The IL-17 family of cytokines in psoriasis: IL-17A and beyond. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1682. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McGeachy MJ, Cua DJ, Gaffen SL. The IL-17 family of cytokines in health and disease. Immunity. 2019;50(4):892–906. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li X, Bechara R, Zhao J, McGeachy MJ, Gaffen SL. IL-17 receptor-based signaling and implications for disease. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(12):1594–1602. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0514-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herjan T, Hong L, Bubenik J, et al. IL-17-receptor-associated adaptor Act1 directly stabilizes mRNAs to mediate IL-17 inflammatory signaling. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(4):354–365. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0071-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bertelsen T, Ljungberg C, Litman T, et al. IκBζ is a key player in the antipsoriatic effects of secukinumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johansen C, Mose M, Ommen P, et al. IκBζ is a key driver in the development of psoriasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(43):E5825–5833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509971112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bertelsen T, Iversen L, Johansen C. The human IL-17A/F heterodimer regulates psoriasis-associated genes through IκBζ. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(9):1048–1052. doi: 10.1111/exd.13722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Golbari NM, Basehore BM, Zito PM. Brodalumab. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2021, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Bimekizumab versus ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE VIVID): efficacy and safety from a 52-week, multicentre, double-blind, active comparator and placebo controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10273):487–498. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00125-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gordon KB, Foley P, Krueger JG, et al. Bimekizumab efficacy and safety in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE READY): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10273):475–486. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00126-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petitpain N, D’Amico F, Yelehe-Okouma M, et al. IL-17 inhibitors and inflammatory bowel diseases: a Postmarketing Study in Vigibase. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loft ND, Vaengebjerg S, Halling AS, Skov L, Egeberg A. Adverse events with IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of Phase III studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(6):1151–1160. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Conrad C, Gilliet M. Psoriasis: from pathogenesis to targeted therapies. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(1):102–113. doi: 10.1007/s12016-018-8668-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chiricozzi A, Caposiena D, Garofalo V, Cannizzaro MV, Chimenti S, Saraceno R. A new therapeutic for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: apremilast. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12(3):237–249. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2016.1134319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li H, Zuo J, Tang W. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1048. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83(12):1583–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parry GC, Mackman N. Role of cyclic AMP response element-binding protein in cyclic AMP inhibition of NF-kappaB-mediated transcription. J Immunol. 1997;159(11):5450–5456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Strober B, Alikhan A, Lockshin B, Shi R, Cirulli J, Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of efficacy in systemic-naive patients with moderate plaque psoriasis: pharmacodynamic results from the UNVEIL study. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;96(3):126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garcet S, Nograles K, Correa da Rosa J, Schafer PH, Krueger JG. Synergistic cytokine effects as apremilast response predictors in patients with psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(3):1010–1013.e1016. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.05.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pincelli C, Schafer PH, French LE, Augustin M, Krueger JG. Mechanisms underlying the clinical effects of apremilast for psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(8):835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.FDA. Drugs@FDA: FDA-approved drugs, New Drug Application (NDA): 205437. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=205437. Accessed March25, 2021.

- 76.Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a Phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Paul C, Cather J, Gooderham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis over 52 weeks: a phase III, randomized controlled trial (ESTEEM 2). Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(6):1387–1399. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stein Gold L, Bagel J, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in systemic- and biologic-naive patients with moderate plaque psoriasis: 52-week results of UNVEIL. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(2):221–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Biotherapeutics A. Topical roflumilast cream; 2021. Available from: https://arcutis.com/trial/arq-151/. Accessed April13, 2021.

- 80.FDA. Drugs@FDA: FDA-approved drugs New Drug Application (NDA): 022522. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=022522. Accessed June11, 2021. Accessed April 13, 2021.

- 81.Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Stein Gold L, et al. Trial of roflumilast cream for chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):229–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nogueira M, Puig L, Torres T. JAK inhibitors for treatment of psoriasis: focus on selective TYK2 inhibitors. Drugs. 2020;80(4):341–352. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01261-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schwartz DM, Kanno Y, Villarino A, Ward M, Gadina M, O’Shea JJ. JAK inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for immune and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(12):843–862. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gadina M, Le MT, Schwartz DM, et al. Janus kinases to jakinibs: from basic insights to clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58(Suppl 1):i4–i16. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.D’Urso DF, Chiricozzi A, Pirro F, et al. New JAK inhibitors for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2020;155(4):411–420. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.20.06658-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hald A, Andrés RM, Salskov-Iversen ML, Kjellerup RB, Iversen L, Johansen C. STAT1 expression and activation is increased in lesional psoriatic skin. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(2):302–310. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Calautti E, Avalle L, Poli V. Psoriasis: a STAT3-centric view. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(1). doi: 10.3390/ijms19010171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Damsky W, King BA. JAK inhibitors in dermatology: the promise of a new drug class. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(4):736–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Papp KA, Menter MA, Abe M, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: results from two randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(4):949–961. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Papp K, Gordon K, Thaçi D, et al. Phase 2 Trial of selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibition in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(14):1313–1321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pfizer. Prescribing Information of Xeljanz. Available from: https://labeling.pfizer.com/showlabeling.aspx?id=959. Accessed June11, 2021. Accessed March 23, 2021.

- 92.FDA. Initial safety trial results find increased risk of serious heart-related problems and cancer with arthritis and ulcerative colitis medicine Xeljanz, Xeljanz XR (tofacitinib). Updated February 2, 2021. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/initial-safety-trial-results-find-increased-risk-serious-heart-related-problems-and-cancer-arthritis. Accessed March 23, 2021.

- 93.Hosking AM, Juhasz M, Mesinkovska NA. Topical Janus kinase inhibitors: a review of applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hennig P, Fenini G, Di Filippo M, Beer HD. Electrophiles against (skin) diseases: more than Nrf2. Biomolecules. 2020;10(2):271. doi: 10.3390/biom10020271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brück J, Dringen R, Amasuno A, Pau-Charles I, Ghoreschi K. A review of the mechanisms of action of dimethylfumarate in the treatment of psoriasis. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(6):611–624. doi: 10.1111/exd.13548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hoogendoorn A, Avery TD, Li J, Bursill C, Abell A, Grace PM. Emerging therapeutic applications for fumarates. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2021;42(4):239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2021.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kobayashi EH, Suzuki T, Funayama R, et al. Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11624. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cuadrado A, Rojo AI, Wells G, et al. Therapeutic targeting of the NRF2 and KEAP1 partnership in chronic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(4):295–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kastrati I, Siklos MI, Calderon-Gierszal EL, et al. Dimethyl fumarate inhibits the nuclear factor κb pathway in breast cancer cells by covalent modification of p65 protein. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(7):3639–3647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.679704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Peng H, Guerau-de-arellano M, Mehta VB, et al. Dimethyl fumarate inhibits dendritic cell maturation via nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) and mitogen stress-activated kinase 1 (MSK1) signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(33):28017–28026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.383380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Andersen JL, Gesser B, Funder ED, et al. Dimethyl fumarate is an allosteric covalent inhibitor of the p90 ribosomal S6 kinases. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4344. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06787-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Geisel J, Brück J, Glocova I, et al. Sulforaphane protects from T cell-mediated autoimmune disease by inhibition of IL-23 and IL-12 in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2014;192(8):3530–3539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kim SW, Lee HK, Shin JH, Lee JK. Up-down regulation of HO-1 and iNOS gene expressions by ethyl pyruvate via recruiting p300 to Nrf2 and depriving it from p65. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mrowietz U, Barker J, Boehncke WH, et al. Clinical use of dimethyl fumarate in moderate-to-severe plaque-type psoriasis: a European expert consensus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(Suppl 3):3–14. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mrowietz U, Szepietowski JC, Loewe R, et al. Efficacy and safety of LAS41008 (dimethyl fumarate) in adults with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, Fumaderm(®) - and placebo-controlled trial (BRIDGE). Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(3):615–623. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.LTD DRSL. Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Limited through its wholly owned subsidiary, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories SA, announces positive topline results from Phase 2b study of PPC-06 in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis; 2019. Available from: https://www.drreddys.com/media/904415/ppc_06_press_release_final_10_06_2019.pdf. Accessed March29, 2021.

- 107.Jetten AM. Retinoid-related orphan receptors (RORs): critical roles in development, immunity, circadian rhythm, and cellular metabolism. Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e003. doi: 10.1621/nrs.07003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pandya VB, Kumar S, Sachchidanand, Sharma R, Desai RC. Combating autoimmune diseases with retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor-γ (RORγ or RORc) inhibitors: hits and misses. J Med Chem. 2018;61(24):10976–10995. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Capone A, Volpe E. Transcriptional regulators of T helper 17 cell differentiation in health and autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. 2020;11:348. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Obinata H, Hla T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and inflammation. Int Immunol. 2019;31(9):617–625. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxz037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Vaclavkova A, Chimenti S, Arenberger P, et al. Oral ponesimod in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9959):2036–2045. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60803-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pharmaceuticals J. Prescribing information label for Ponvory; 2021. Available from: https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/PONVORY-pi.pdf. Accessed March25, 2021.

- 113.Information JM. Use of PONVORY in patients with psoriasis or other autoimmune disorders; 2021. Available from: https://www.janssenmd.com/ponvory/clinical-data/clinical-studies/use-of-ponvory-in-patients-with-psoriasis-or-other-autoimmune-disorders. Accessed March25, 2021.

- 114.FDA. Drugs@FDA: FDA-approved drugs, New Drug Application (NDA): 213498; 2021. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=213498. Accessed March25, 2021.

- 115.Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, Tallman AM, Armstrong A. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(4):1059–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Quintana FJ. Regulation of the immune response by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Immunity. 2018;48(1):19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Smith SH, Jayawickreme C, Rickard DJ, et al. Tapinarof is a natural ahr agonist that resolves skin inflammation in mice and humans. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(10):2110–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lebwohl M. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety in two pivotal Phase 3 Trials. EADV Virtual; October 29–31, 2020; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dermavant. Positive data from PSOARING 3 support long-term use of tapinarof cream in adults with plaque psoriasis, with durable (on-therapy) and remittive (off-therapy) benefits; 2021. [updated February 18, 2021]. Available from: https://www.dermavant.com/positive-data-from-psoaring-3-support-long-term-use-of-tapinarof-cream-in-adults-with-plaque-psoriasis-with-durable-on-therapy-and-remittive-off-therapy-benefits/. Accessed March25, 2021.

- 120.Cohen S, Barer F, Itzhak I, Silverman MH, Fishman P. Inhibition of IL-17 and IL-23 in human keratinocytes by the A(3) adenosine receptor agonist piclidenoson. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:2310970. doi: 10.1155/2018/2310970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fishman P, Cohen S. The A3 adenosine receptor (A3AR): therapeutic target and predictive biological marker in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(9):2359–2362. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3202-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.David M, Gospodinov DK, Gheorghe N, et al. Treatment of plaque-type psoriasis with oral CF101: data from a Phase II/III Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(8):931–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Costa T, Raghavendra NM, Penido C. Natural heat shock protein 90 inhibitors in cancer and inflammation. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;189:112063. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang C, Wu L, Bulek K, et al. The psoriasis-associated D10N variant of the adaptor Act1 with impaired regulation by the molecular chaperone hsp90. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(1):72–81. doi: 10.1038/ni.2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Stenderup K, Rosada C, Gavillet B, Vuagniaux G, Dam TN. Debio 0932, a new oral Hsp90 inhibitor, alleviates psoriasis in a xenograft transplantation model. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(6):672–676. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hansen RS, Thuesen KKH, Bregnhøj A, et al. The HSP90 inhibitor RGRN-305 exhibits strong immunomodulatory effects in human keratinocytes. Exp Dermatol. 2021. doi: 10.1111/exd.14302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]