Abstract

Background:

Maternal mortality is higher among Black compared to White people in the United States. Whether Black-White disparities in maternal in-hospital mortality during the delivery hospitalization vary across hospital types (Black-serving vs. non-Black-serving and teaching vs. non-teaching) and whether overall maternal mortality differs across hospital types is not known.

Objectives:

1) Determine whether risk-adjusted Black-White disparities in maternal mortality during the delivery hospitalization vary by hospital types – this is analysis of disparities in mortality within hospital types. 2) Compare risk-adjusted in-hospital maternal mortality among Black-serving and non-Black-serving teaching and non-teaching hospitals regardless of race – this is an analysis of overall mortality across hospital types.

Study design:

We performed a population-based, retrospective cohort study of 5,679,044 deliveries among Black (14.2%) and White (85.8%) patients in three states (CA, MO, PA) from 1995–2009. A hospital discharge disposition of “death” defined maternal in-hospital mortality. Black-serving hospitals had at least 7% Black obstetric patients (top quartile). We performed risk adjustment by calculating expected death rates using predictions from logistic regression models incorporating sociodemographics, rurality, comorbidities, multiple gestations, gestational age at delivery, year, state, and mode of delivery. We calculated risk-adjusted risk ratios of mortality by comparing observed:expected ratios among Black and White patients within hospital types and then examined mortality across hospital types, regardless of patient race. We quantified the proportion of Black-White disparities in mortality attributable to delivering in Black-serving hospitals using causal mediation analysis.

Results:

There were 330 maternal deaths among 5,679,044 patients (5.8 per 100,000). Black patients died more often (11.5 per 100,000) than White patients (4.8 per 100,000) (RR 2.38, 95% CI: 1.89–2.98). Examination of Black-White disparities revealed that after risk adjustment, Black patients had significantly greater risk of death (adjusted RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.17–1.79) and that the disparity was similar within each of the hospital types. Comparison of mortality, regardless of race, across hospital types, revealed that among teaching hospitals, mortality was similar in Black-serving and non-Black-serving hospitals. However, among non-teaching hospitals, mortality was significantly higher in Black-serving versus non-Black-serving hospitals (adjusted RR 1.47, 95% CI: 1.15–1.87). Notably, 53% of Black patients delivered in non-teaching, Black-serving hospitals, compared with just 19% of White patients. Among non-teaching hospitals, 47% of Black-White disparities in maternal in-hospital mortality attributable to delivering at Black-serving hospitals.

Conclusion:

Maternal in-hospital mortality during the delivery hospitalization among Black patients is more than double that of White patients. Our data suggest this disparity is due to both excess mortality among Black patients within each hospital type, in addition to excess mortality in non-teaching, Black-serving hospitals where most Black patients deliver. Addressing downstream effects of racism to achieve equity in maternal in-hospital mortality will require transparent reporting of quality metrics by race to reduce differential care and outcomes within hospital types, improvements in care delivery at Black-serving hospitals, overcoming barriers to accessing high-quality care among Black patients, and eventually desegregation of healthcare.

Keywords: Maternal mortality, maternal morbidity, racial disparities, health services, in-patient mortality, pregnancy, cohort study, population study, health equity, racism

INTRODUCTION

After decades of decline, maternal mortality in the United States has steadily risen from 7.2 per 100,000 live births in 1987 to 17.4 in the most recent data from 2018.1–3 Of major concern are ongoing racial disparities in maternal mortality; Black patients are more than twice as likely to die than White patients (37.3 versus 14.9 per 100,000 live births).1, 2 Reasons for racial disparities in maternal mortality are multifactorial.4 While lifelong exposures to social and environmental inequities due to structural racism5 affect risks of contributing comorbid conditions such as obesity and hypertension,6 racism in hospitals and communities may lead to worse medical care and adverse outcomes among Black patients.7, 8

Prior studies have suggested that approximately half of maternal mortality is preventable, and that 90% of preventable deaths may be attributable to provider factors such as delayed diagnoses.9–11 Further while there is rigorous work on hospital factors associated with severe maternal morbidity,12, 13 less is known about maternal mortality during the delivery hospitalization because it is a rarer outcome. Thus, it is important to identify hospital factors that may be drivers of disparities in in-hospital mortality. Patients choose delivery hospitals for various reasons that may include geography, hospital reputation or quality, and insurance coverage.14 Hospitals differ with respect to the demographic composition of their patients.13 Prior studies have shown that low-income and patients of color often receive care at lower quality hospitals,15 including obstetric care.13 Hospital factors that have been implicated in maternal in-hospital severe morbidity and mortality include lack of a 24-hour on-site anesthesiologist, hospital volume (low and high), time of day, and staffing.16, 17

Another potential driver of differential maternal in-hospital mortality may be teaching status. Teaching hospitals often care for more complex patients.18 While care quality is often higher in teaching hospitals, patient satisfaction scores are often lower.19 Since patient satisfaction can correlate with interpersonal interactions and communication which can vary based on implicit bias,20, 21 our hypothesis was that racial disparities in in-hospital maternal mortality may differ based on teaching status. Due to potential differences in cultural competence that may flow from exposure to diverse patients (emersion),22 our second hypothesis was that disparities would be larger in hospitals that care for a lower proportion of Black patients.

MATERIALS and METHODS

We used linked birth certificate and hospital discharge data from California, Missouri and Pennsylvania from 1995–200923 to compare maternal in-hospital mortality ratios for non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White patients (n=5,679,044), hereafter designated as Black and White for brevity. Race/ethnicity was self-designated on the birth certificate. All other race/ethnicities were excluded in this analysis.

The primary outcome was maternal death before discharge during the birth hospitalization. We used a hospital discharge disposition of “death” to determine whether a patient died during the hospital stay. We analyzed two primary exposures: teaching status and Black-serving status. Hospital teaching status was obtained from the American Hospital Association database and linked using the hospital identifier. We calculated the percentage of patients who delivered who were Black at each hospital to generate quartiles and compared the top Black-serving hospital quartile (“Black-serving”) to the bottom three quartiles (“non-Black-serving”); hospitals with > 7.08% Black patients were considered “Black-serving.” This threshold was chosen to be consistent with a prior study of severe maternal morbidity by Howell et al. in which low Black-serving hospitals were the lowest three quartiles of the proportion of Black patients served.12 This designation was specific to the obstetric population. Hospitals could move in and out of each quartile as their demographics changed annually.

We performed risk adjustment using observed:expected (O:E) ratios.24 To generate expected rates of death, we performed a logistic regression model with the dependent variable of death and the following independent variables: maternal age; insurance; gestational age at delivery; multiple gestations; mode of delivery; rurality; year; pregnancy comorbid conditions (chronic hypertension, chronic cardiac disease, diabetes, chronic renal disease) from hospital diagnosis codes; and state of delivery (CA, MO, PA). We obtained predicated probabilities of death for each variable from the regression models using the “predict” command in STATA25 and summed the probabilities to obtained expected death rates within strata of interest.

There were two primary comparisons made. First, we compared mortality among Black patients to mortality among White patients overall and within each hospital type by calculating Black/White risk-adjusted risk ratios using O:E/O:E.26 We dichotomized hospital types in two ways: teaching versus non-teaching and then Black-serving versus non-Black-serving. Then we created four mutually-exclusive hospital types (teaching Black-serving; teaching non-Black-serving; non-teaching Black-serving; and non-teaching non-Black-serving). Second, we used the same technique (O:E/O:E) to compare risk-adjusted mortality among all patients (Black and White), regardless of race, in the four mutually-exclusive hospital types; these were analyses across hospital types. In each analysis, we generated 95% confidence intervals by bootstrapping with 1000 iterations.27, 28

We also quantified the proportion of the racial disparity in maternal in-hospital mortality explained by delivering at Black-serving vs. non-Black-serving hospitals in models stratified by teaching status using VanderWeele’s approach to causal mediation.29 We used adjusted log-binomial regression with death as the dependent variable, Black race as the independent variable, and delivering at a Black-serving hospital as the mediator. We included the same covariates in the model as we did in the model used for risk-adjustment.

With respect to missing data, only rural/urban status was missing among non-teaching hospitals for 19,279 deliveries (0.3%) and these deliveries were included in the reference (large urban) group given it was the most common setting (95.5%). This study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board. Statistical analyses were performed using both SAS 9.4, Cary, NC and STATA 16, College Station, TX.

RESULTS

Patient and hospital demographics are presented in Table 1. Patients delivering at teaching hospitals had a higher prevalence of all comorbidities compared to patients delivering at non-teaching hospitals. In contrast, the prevalence of comorbidities was similar in Black-serving compared to non-Black-serving hospitals. There were 330 deaths among the 5,679,044 live births (5.3 per 100,000) during the delivery hospitalization.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 5,679,044 deliveries from California, Missouri and Pennsylvania, 1995–2009.

| Teaching | Non-Teaching | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Black-serving | Black-serving | Non-Black-serving | Black-serving | |

| n= 316,369 | n= 600,406 | n= 3,392,721 | n= 1,369,548 | |

| Characteristic (n=5,679,044) | Col. % | Col. % | Col. % | Col. % |

| Maternal age | ||||

| <25 | 26.9 | 28.5 | 28.9 | 36.2 |

| 25– <35 | 55.3 | 51.5 | 53.6 | 49.0 |

| ≥ 35 | 17.8 | 20.0 | 17.6 | 14.7 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 8.6 | 33.3 | 4.8 | 32.5 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 91.4 | 66.7 | 95.2 | 67.5 |

| Insurance Category | ||||

| Private | 69.0 | 63.7 | 68.3 | 56.4 |

| Medicaid | 27.8 | 33.8 | 27.6 | 38.5 |

| Other insurance | 3.2 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 5.1 |

| Preterm (<37 weeks’ gestation) | 12.7 | 12.8 | 8.3 | 10.7 |

| Multiple gestation | 3.6 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| Cesarean delivery | 26.7 | 29.2 | 27.6 | 26.5 |

| State | ||||

| CA | 32.8 | 24.8 | 62.8 | 55.7 |

| MO | 16.9 | 16.8 | 17.0 | 19.5 |

| PA | 50.3 | 58.4 | 20.2 | 24.8 |

| Rural/Urban* | ||||

| Large metro | 94.4 | 98.5 | 77.6 | 95.5 |

| Small metro | 0.2 | 1.5 | 9.6 | 1.6 |

| Rural | 5.5 | 0.0 | 12.4 | 2.6 |

| Maternal morbidity | ||||

| Chronic cardiac disease | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Gestational diabetes | 5.2 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Chronic hypertension | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

| Gestational hypertension | 4.8 | 5.8 | 3.0 | 3.6 |

| Chronic renal disease | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Acute renal failure | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Epoch | ||||

| 1995–1999 | 39.5 | 25.2 | 33.9 | 38.4 |

| 2000–2004 | 33.5 | 32.2 | 33.8 | 31.3 |

| 2005–2009 | 27.1 | 42.7 | 32.3 | 30.3 |

Missing data: Rural/urban status was missing for n=19,279 deliveries (0.3%).

Black-White disparities in maternal in-hospital mortality within hospital types

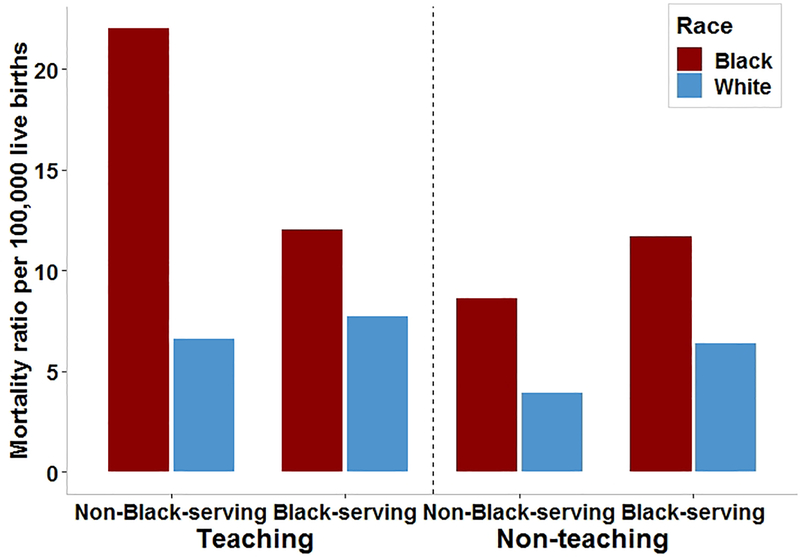

Black patients (11.5 per 100,000) were more than twice as likely as White patients (4.8 per 100,000) to die in the hospital (RR 2.38, 95% CI: 1.88–3.02). The risk-adjusted mortality ratio was significantly higher among Black patients compared to White patients (O:E/O:E, adjusted RR 1.44, 95% CI: 1.17–1.79) (Table 2). In each hospital type, Black patients had a higher unadjusted risk of death compared to White patients (Figure 1). After risk adjustment, the point estimates comparing Black to White patients were similar, but only in non-teaching hospitals was the mortality ratio significantly higher among Black patients than White patients (Table 2). Including teaching status and Black-serving status together revealed a similar increase in mortality risk among Black compared to White patients (Table 3).

Table 2.

Black-White disparities in maternal in-hospital mortality overall and by hospital teaching and Black-serving status

| Hospital Type | n (col %) | Deaths n (ratio per 100,000 live births) | Black-White Unadjusted (Observed) RR (95% CI) | Black-White Expected* RR (95% CI) | Black-White Adjusted^ RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All hospitals | |||||

| Black patients | 835,120 (14.7) | 96 (11.5) | 2.38 (1.89–3.02) | 1.65 (1.51–1.79) | 1.44 (1.17–1.79) |

| White patients | 4,843,924 (85.3) | 234 (4.8) | ref | ref | ref |

| Teaching status | |||||

| Teaching | |||||

| Black patients | 227,249 (24.8) | 30 (13.2) | 1.86 (1.18–2.93) | 1.31 (1.20–1.45) | 1.42 (0.90–2.15) |

| White patients | 689,526 (75.2) | 49 (7.1) | ref | ref | ref |

| Non-teaching | |||||

| Black patients | 607,871 (12.8) | 66 (10.9) | 2.44 (1.84–3.23) | 1.72 (1.57–1.87) | 1.42 (1.09–1.86) |

| White patients | 4,154,398 (87.2) | 185 (4.5) | ref | ref | ref |

| Black-serving status | |||||

| Non-Black-serving | |||||

| Black patients | 189,474 (5.1) | 20 (10.6) | 2.56 (1.61–4.09) | 1.82 (1.67–1.98) | 1.41 (0.88–2.16) |

| White patients | 3,519,616 (94.9) | 145 (4.1) | ref | ref | ref |

| Black-serving | |||||

| Black patients | 645,646 (32.8) | 76 (11.8) | 1.75 (1.29–2.38) | 1.42 (1.31–1.53) | 1.23 (0.95–1.69) |

| White patients | 1,324,308 (67.2) | 89 (6.7) | ref | ref | ref |

Expected calculated using predictions from logistic regression model to predict death that included maternal age, insurance, gestational age at delivery, multiple gestations, mode of delivery, rurality, year, pregnancy comorbid conditions (chronic hypertension, chronic cardiac disease, diabetes, chronic renal disease), and state of delivery (CA, MO, PA)

Adjusted RR calculated as (Black O:E)/(White O:E), O:E observed/expected

Figure 1.

Crude (unadjusted) maternal in-hospital mortality ratios per 100,000 live births by race, hospital teaching and Black-serving status.

Table 3.

Black-White disparities in maternal in-hospital mortality in by both teaching and Black-serving status

| Hospital Type | Deaths n (ratio per 100,000 live births) | Black-White Unadjusted (Observed) RR (95% CI) | Black-White Expected* RR (95% CI) | Black-White Adjusted RR^ (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching | ||||

| Non-Black-serving | ||||

| Black patients | 6 (22.0) | 3.35 (1.34–8.38) | 1.91 (1.70–2.18) | 1.75 (0.57–4.26) |

| White patients | 19 (6.6) | ref | ref | |

| Black-serving | ||||

| Black patients | 24 (12.0) | 1.60 (0.94–2.74) | 1.21 (1.10–1.35) | 1.32 (0.81–2.22) |

| White patients | 30 (7.7) | ref | ref | |

| Non-teaching | ||||

| Non-Black-serving | ||||

| Black patients | 14 (8.6) | 2.21 (1.27–3.84) | 1.75 (1.61–1.91) | 1.26 (0.69–2.06) |

| White patients | 126 (3.9) | ref | ref | |

| Black-serving | ||||

| Black patients | 52 (11.7) | 1.83 (1.26–2.65) | 1.53 (1.41–1.63) | 1.20 (0.84–1.74) |

| White patients | 59 (6.4) | ref | ref | |

Expected calculated using predictions from logistic regression model to predict death that included maternal age, insurance, gestational age at delivery, multiple gestations, mode of delivery, rurality, year, pregnancy comorbid conditions (chronic hypertension, chronic cardiac disease, diabetes, chronic renal disease), and state of delivery (CA, MO, PA)

Adjusted RR calculated as (Black O:E)/(White O:E), O:E, observed/expected

Maternal in-hospital mortality across hospital types, regardless of race

The majority (53%) of Black patients delivered at non-teaching Black-serving hospitals compared to just 19% of White patients (Table 4). Patients delivering at teaching hospitals, regardless of Black-serving status, had a higher mortality ratio (8.6 per 100,000) compared with non-teaching hospitals (5.3 per 100,000) (P<0.001). The mortality ratio was also higher in Black-serving hospitals (8.4 per 100,000) compared to non-Black-serving hospitals (4.5 per 100,000) (P<0.001). Among teaching hospitals, overall mortality in Black-serving (9.0 per 100,000) and non-Black-serving (7.9 per 100,000) hospitals was statistically similar in unadjusted (RR 1.14, 95% CI: 0.74–1.86) and risk-adjusted (adjusted RR 1.09, 95% CI: 0.71–1.75) analyses (Table 4). In contrast, in non-teaching hospitals, the mortality ratio was nearly double in Black-serving (8.1 per 100,000) compared non-Black-serving (4.1 per 100,000) hospitals (RR 1.96, 95% CI: 1.52–2.56), an association that persisted after risk adjustment (adjusted RR 1.47, 95% CI: 1.15–1.87).

Table 4.

Maternal in-hospital mortality, regardless of race among all Black and White patients, during the delivery hospitalization by teaching and Black-serving status (n=5,679,044 deliveries)

| Hospital Type | Deliveries, column% | Deliveries among Black patients, column % | Deliveries among White patients, column % | Deaths n (ratio per 100,000 live births) | Black-serving vs. non-Black-serving Unadjusted (Observed) RR of death (95% CI) | Expected* RR (95% CI) | Black-serving vs. non-Black-serving Adjusted RR^ of death (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching | |||||||

| Non-Black-serving | 5.6 | 3.3 | 6.0 | 25 (7.9) | ref | ref | ref |

| Black-serving | 34.5 | 23.9 | 8.3 | 54 (9.0) | 1.14 (0.71–1.83) | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | 1.09 (0.71–1.75) |

| Non-teaching | |||||||

| Non-Black-serving | 71.2 | 19.4 | 66.7 | 140 (4.1) | ref | ref | ref |

| Black-serving | 28.8 | 53.4 | 19.1 | 111 (8.1) | 1.96 (1.53–2.52) | 1.34 (1.25–1.44) | 1.47 (1.15–1.87) |

Expected calculated using predictions from logistic regression model to predict death that included maternal age, insurance, gestational age at delivery, multiple gestations, mode of delivery, rurality, year, pregnancy comorbid conditions (chronic hypertension, chronic cardiac disease, diabetes, chronic renal disease), and state of delivery (CA, MO, PA)

Adjusted RR calculated as (Black-serving O:E)/(Non-Black-serving O:E), O:E, observed/expected

Proportion of Black-White disparity explained by hospital type

In the final analysis, stratified by teaching-status, we performed two causal mediation analyses to quantify the proportion of the Black-White disparity in adjusted maternal in-hospital mortality explained by delivering in a Black-serving hospital. Among teaching hospitals, delivering at a Black-serving hospital did not explain any of the Black-White disparity (proportion mediated 0.015, P=0.95). In contrast, 47% of the Black-White disparity in non-teaching hospitals, was attributable to delivering at a Black-serving hospital (proportion mediated 0.473, P = 0.01).

COMMENT

Principal Findings

In this population-based study of births from California, Missouri and Pennsylvania, we demonstrated two important findings. First, there are large racial disparities in maternal mortality during the delivery hospitalization that persist after risk adjustment for medical comorbidities. Second, in non-teaching Black-serving hospitals, where 53% of Black patients and just 19% of White patients deliver, risk-adjusted mortality ratios are significantly higher than in non-teaching non-Black serving hospitals regardless of race; 47% of the Black-White disparity in maternal in-hospital mortality in non-teaching hospitals is attributable to delivering at Black-serving hospitals.

Results in the Context of What is Known

There are several potential reasons why Black patients die more often than White patients during the delivery admission. One possibility is that Black patients have a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions6 that lead to an increased risk of mortality. Attenuation of the racial disparity in our adjusted model suggests that this is part of the answer. However, the persistence of an overall racial disparity after risk adjustment suggests that differences in underlying conditions is not the sole reason for inequity in maternal in-hospital mortality.

Another potential explanation for racial disparities in maternal in-hospital mortality is that Black patients receive worse care than White patients within a given hospital or hospital type, leading to an increased risk of death. While the numbers became quite small in each type of hospital, we did observe significant racial disparities within non-teaching hospitals with similar but non-significant effects in other hospital types after risk adjustment. These findings suggest that even within hospital types, Black patients with similar comorbid conditions remain at increased risk of death compared to White patients. This is consistent with an analysis of surgical outcomes using Medicare claims data. Silber et al found that death from “failure to rescue” after surgery was less common in teaching-intensive hospitals with high resident:bed ratios, but that this benefit was observed only among White, but not Black, patients.30 The authors postulate that racial differences in monitoring and communication may contribute to higher mortality due to failure to rescue.

Another likely contributor to racial disparities is that the hospitals where most Black patients deliver may be of lower quality and thus, as a population, Black patients experience worse care. Indeed, there are data in the literature to support this hypothesis. A study of data from seven states in the U.S. found that Black-serving (compared with White-serving) hospitals performed worse on 12 of 15 delivery-quality indicators that included measures such as complicated cesarean delivery, obstetric trauma, wound infection, etc.8 Howell and colleagues studied racial disparities in severe maternal morbidities using the National Inpatient Sample, and showed that 74% of all deliveries among Black patients occur in 25% of hospitals and that just 18% of deliveries among White patients occur in those same hospitals.12 Howell et al also analyzed population-based New York City data and found that hospital variation in quality contributes to racial disparities in maternal morbidity, estimating that site differences may account for to up to 47% of racial disparities in severe morbidities.13 Our data also support the possibility that the hospitals where Black patients deliver contributes to increased mortality risk because both Black and White patients had higher mortality ratios in Black-serving non-teaching hospitals (where most Black patients deliver) compared to non-Black-serving non-teaching hospitals. Our findings were strikingly similar to those of Howell et al, in that we also found that among non-teaching hospitals, delivering at a Black-serving hospital may account for 47% of the racial disparity in maternal in-patient mortality.

Clinical Implications

Reducing maternal mortality and narrowing the Black-White gap in in-hospital mortality will require understanding and ameliorating the drivers of mortality. While reducing disparities in comorbid conditions such as hypertension and diabetes prior to pregnancy is likely to decrease disparities in mortality,31 it would be insufficient. Our finding of higher risk-adjusted mortality among Black patients within hospital types suggests that there may be differences in care even among similar patients in similar settings by race that should be addressed. It is crucial to identify the most important targets for interventions32 within hospital types, which may include differential communication, lack of cultural competency, and implicit bias.33, 34 Transparent hospital reporting of maternal morbidity and mortality in hospital quality dashboards by race should become the norm,35 as it may identify structural factors that potentiate inequities within hospital types.

Our finding that regardless of race, risk-adjusted mortality is particularly high in Black-serving non-teaching hospitals where most Black patients deliver, suggests that lower quality care or lack of proactive transferring to sites with higher levels of care, also contributes to excess mortality among Black patients. We need to determine why care quality is worse at these hospitals. Explanations may include financial constraints due to pay-for-performance incentives that benefit high-performing hospitals as well as differential care practices.36–38 It is also important to determine why patients choose the hospitals they do. While it is often assumed that patients choose hospitals closest to home and that those hospitals are of lower quality in Black neighborhoods,39 the literature does not necessarily support that hypothesis. In a study of Medicare patients, Dimock et al found that Black patients tended to live closer to high quality hospitals but were more likely to have high-risk surgery at low-quality hospitals than White patients.40 A proposed solution to motivate patients to choose higher quality hospitals has been transparent, public reporting of quality and performance.41 However, studies of public reporting are inconsistent with respect to improvement in care quality or consumer decisions.42, 43 Whether patients are unaware of quality metrics, or prioritize other factors in choosing a delivery hospital is unknown. Nonetheless, since patients can choose where to deliver, policies and incentives to desegregate healthcare may help reduce disparities. Additionally, hospital or unit closures may improve outcomes by removing the option to deliver at a poorly-performing hospital.44

Research Implications

Further investigation into the drivers of disparities within hospital types as well as hospital characteristics across hospital types that may contribute to differential risk of maternal mortality is warranted. Quality improvement efforts should be studied with respect to their impact on racial disparities in maternal outcomes. Hospitals that perform well with respect to racial disparities should serve as potential models of care and share their practices through perinatal collaboratives that are arising across the country. Dissemination and implementation of potentially better practices in local environments should be examined to ensure that their well-intended efforts narrow the Black-White gap in maternal outcomes. With respect to studying differential performance among Black-serving hospitals, our findings could motivate investigation of policies to better support Black-serving hospitals as well as policies to incentivize desegregation of obstetric care.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include its large population-based sample from three states over 15 years, allowing for analysis of rare events such as maternal in-hospital mortality. Linkage with birth certificate and hospital data allowed for risk adjustment to ascertain if differences in mortality by race were confounded by severity of illness in different types of hospitals. Like all studies of observational data, it is possible that our data do not enable complete risk-adjustment. However, since the focus of our study was on disparities within and across hospital types, there would have had to have been differential reporting of risk factors by race or hospital type, for incomplete risk adjustment to introduce bias. It possible that factors surrounding the hospital (as opposed to hospital policies themselves) could have confounded the association Black-serving hospitals and higher in-hospital mortality, but adjustment for rural/urban status did not nullify the association.

Our data were limited to the delivery hospitalization and as such, we cannot analyze pregnancy-related mortality which is defined by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as death within one year of a pregnancy “from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.”7 However, our in-hospital mortality ratio was similar to a study of data from the Hospital Corporation of America, which reported 6.4 per 100,000 births.45 Furthermore, even though the dataset was large, the number of deaths was not, which can lead to less stable estimates and an inability to used fixed effects models since many hospitals had no deaths. We also may have been underpowered to detect differences by hospital types, as shown by wide confidence intervals. While point estimates of Black-White disparities point estimates were similar across hospital types, differences between hospital types cannot be ruled out. Datasets of this type take years to link and rely on states’ willingness to share their data. Thus, the most recent linked data that included all three states were from 2009 and future work will require analysis of more recent data when they are available. We limited our analysis to Black and White patients due to the known disparity between these populations, but as such cannot make conclusions about patients who do not self-identify as either of these groups on their birth certificates.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our data suggest that Black-White racial disparities in maternal mortality are not limited to the period after discharge, and thus may be amenable to improvements in care during the delivery hospitalization. Identifying factors that lead to differences in death rates by race within hospital types as well as overall higher risk of death, regardless of race, in Black-serving hospitals will be critical to reducing disparities. In healthcare, we can work to address the consequences of racism by tracking patient satisfaction, severe morbidities, medical errors, and mortality by race/ethnicity. Achieving equity in maternal in-hospital mortality will likely require improving care delivery at Black-serving hospitals, understanding and overcoming barriers to accessing high-quality care among Black patients, and ultimately, desegregating healthcare.

Supplementary Material

AJOG at a Glance:

This section is limited to no more than 130 words, 1–3 short sentences or phrases.

A. Why was the study conducted?

Black women die from pregnancy-related causes at 4 times the rate of White women.

We sought to determine whether disparities and overall maternal in-hospital mortality differed by hospital type (Black- and non-Black-serving, teaching and non-teaching).

B. What are the key findings?

Risk-adjusted maternal in-hospital mortality was 44% higher among Black vs. White patients, regardless of hospital type.

Risk-adjusted mortality in non-teaching hospitals, regardless of patient race, was significantly higher in Black-serving vs. non-Black-serving hospitals; 53% of Black and 19% of White patients deliver in these hospitals.

C. What does this study add to what is already known?

The contribution of healthcare to in-hospital mortality, which may be preventable, is less well-studied than overall maternal mortality.

To address the repercussions of racism in healthcare, our findings call for reporting of maternal outcomes within hospitals by race, tackling drivers of lower quality care in Black-serving hospitals, and desegregating healthcare.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge the departments of public health from each of the states (CA, MO, PA) for sharing the data making this analysis possible.

Funding: This work was supported by funds from NIH (R01HD084819), AHRQ Grant No. R01HS018661, and the Department of Pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest statement: None of the authors has a conflict of interest or financial interest to disclose.

Condensation: Black-white disparities in maternal in-hospital mortality occur in all hospital types, but are also due to high mortality rates where most Black women deliver.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Maternal mortality, 2020.

- 2.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med 2005;61:1576–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson DB, Moniz MH, Davis MM. Population-level factors associated with maternal mortality in the United States, 1997–2012. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creanga AA, Berg CJ, KO JY, et al. Maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States: where are we now? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, MclemorE MR. On Racism: A New Standard For Publishing On Racial Health Inequities Health Affairs Blog, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/.

- 6.Metcalfe A, Wick J, Ronksley P. Racial disparities in comorbidity and severe maternal morbidity/mortality in the United States: an analysis of temporal trends. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2018;97:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howell EA. Reducing Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2018;61:387–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Kuklina E, Shilkrut A, Callaghan WM. Performance of racial and ethnic minority-serving hospitals on delivery-related indicators. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:647 e1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geller SE, Rosenberg D, COX SM, et al. The continuum of maternal morbidity and mortality: factors associated with severity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191:939–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cmace. Saving Mothers’ Lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–08. The Eighth Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom (vol 118, pg 1 2011). Bjog-Int J Obstet Gy 2015;122:E1–E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg CJ, Harper MA, Atkinson SM, et al. Preventability of pregnancy-related deaths - Results of a state-wide review. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:1228–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:122 e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phibbs CS, Mark DH, Luft HS, et al. Choice of hospital for delivery: a comparison of high-risk and low-risk women. Health Serv Res 1993;28:201–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Low-quality, high-cost hospitals, mainly in South, care for sharply higher shares of elderly black, Hispanic, and medicaid patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1904–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Huang Y, D’Alton ME, WrighT JD. Hospital delivery volume, severe obstetrical morbidity, and failure to rescue. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:795 e1–95 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouvier-Colle MH, Ould El Joud D, Varnoux N, et al. Evaluation of the quality of care for severe obstetrical haemorrhage in three French regions. BJOG 2001;108:898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS. Teaching hospitals and quality of care: a review of the literature. Milbank Q 2002;80:569–93, v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahian DM, Nordberg P, Meyer GS, et al. Contemporary performance of U.S. teaching and nonteaching hospitals. Acad Med 2012;87:701–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and Implicit Bias: How Doctors May Unwittingly Perpetuate Health Care Disparities. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:1504–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health 2015;105:E60–E76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev 2000;57 Suppl 1:181–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bozzuto L, Passarella M, Lorch S, Srinivas S. Effects of Delivery Volume and High-Risk Condition Volume on Maternal Morbidity Among High-Risk Obstetric Patients. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:261–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtin LR, Klein RJ. Direct standardization (age-adjusted death rates). Healthy People 2000 Stat Notes 1995:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsu J, Qin X, Beavers SF, Mirabelli MC. Asthma-Related School Absenteeism, Morbidity, and Modifiable Factors. Am J Prev Med 2016;51:23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iezzoni LI. Risk Adjustment for Measuring Health Care Outcomes. . Number of pages.

- 27.Hall P, Wilson SR. Two Guidelines for Bootstrap Hypothesis Testing. Biometrics 1991;47:757–62. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mooney CZ, Duva RD. Bootstrapping. A Nonparametric Approach to Statistical Inference. SAGE Publications, Inc; Number of pages. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanderweele TJ. Mediation Analysis: A Practitioner’s Guide. Annu Rev Public Health 2016;37:17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Romano PS, et al. Hospital teaching intensity, patient race, and surgical outcomes. Arch Surg 2009;144:113–20; discussion 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu MC. Reducing Maternal Mortality in the United States. JAMA 2018;320:1237–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams DR, Rucker TD. Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health Care Financ Rev 2000;21:75–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagiwara N, Elston Lafata J, Mezuk B, Vrana SR, Fetters MD. Detecting implicit racial bias in provider communication behaviors to reduce disparities in healthcare: Challenges, solutions, and future directions for provider communication training. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1738–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (Book). Choice: Current Reviews for Academic Libraries; 2003;40:1780. [Google Scholar]

- 35.HANLON C, ROSENTHAL J, HINKLE L. State Documentation of Racial and Ethnic Health Dispariteis to Inform Strategic Action. H CUP Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Epstein AM. Health care in America--still too separate, not yet equal. N Engl J Med 2004;351:603–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casalino LP, Elster A, Eisenberg A, Lewis E, Montgomery J, Ramos D. Will pay-for-performance and quality reporting affect health care disparities? Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:w405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akinleye DD, Mcnutt LA, Lazariu V, McLaughlin CC. Correlation between hospital finances and quality and safety of patient care. PLoS One 2019;14:e0219124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jha AK. Racial Disparities In Health Care: Justin Dimick And Coauthors’ June Health Affairs Study: Health Affairs, 2013. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20130604.031758/full/.

- 40.Dimick J, Ruhter J, Sarrazin MV, Birkmeyer JD. Black patients more likely than whites to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals in segregated regions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1046–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.In: Yong PL, Saunders RS, Olsen LA, eds. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Washington (DC), 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, Damberg C, Shekelle PG. Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:111–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ketelaar NA, Faber MJ, Flottorp S, Rygh LH, Deane KH, Eccles MP. Public release of performance data in changing the behaviour of healthcare consumers, professionals or organisations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD004538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorch SA, Srinivas SK, Ahlberg C, Small DS. The impact of obstetric unit closures on maternal and infant pregnancy outcomes. Health Serv Res 2013;48:455–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark SL, Christmas JT, Frye DR, Meyers JA, Perlin JB. Maternal mortality in the United States: predictability and the impact of protocols on fatal postcesarean pulmonary embolism and hypertension-related intracranial hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;211:32 e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.