CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old Caucasian male smoker (80 pack-years) with a history of Crohn disease, presented for emergent evaluation of visual loss associated with 10/10 shooting, pulsatile pain radiating vertically through the paramedian right frontoparietal area. Four days prior to presentation, he developed a right-sided temporal headache and sudden vision loss to “complete blackness” while watching television. His vision improved partially thereafter. An outside hospital interpreted his computed tomography angiography (CTA) imaging as showing complete occlusion of the right internal carotid artery (ICA). Brain MRI showed multiple foci of acute/subacute ischemia involving the right basal ganglia and subcortical white matter. The patient was discharged on daily aspirin 81 mg.

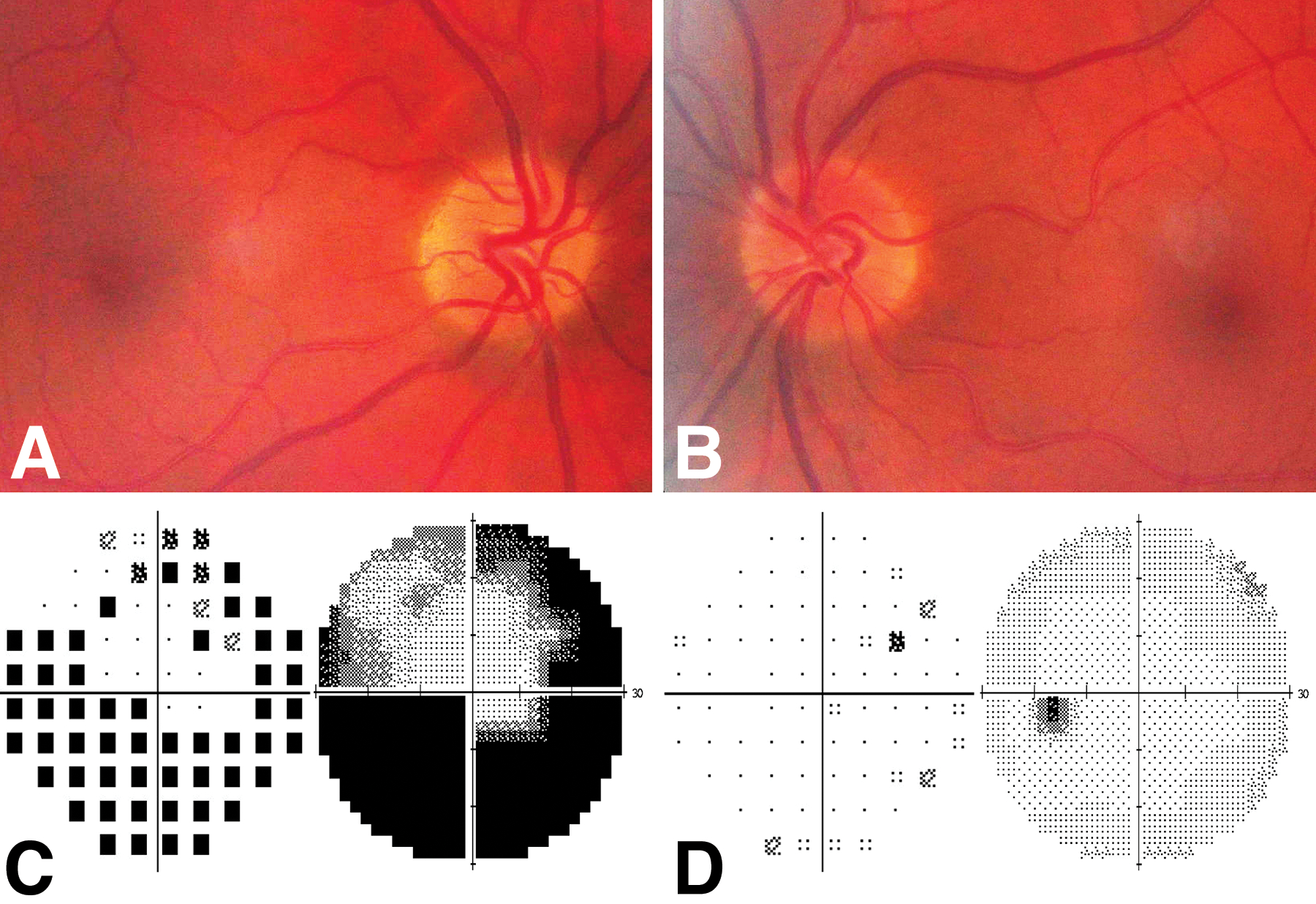

Further subjective decline in vision and increasing pain prompted his emergent presentation for neuro-ophthalmic evaluation. Visual acuity was count fingers at 6’ OD and 20/20 OS. A prominent relative afferent pupillary defect was present on the right without anisocoria. Extraocular motility, intraocular pressure and anterior segment examinations were unremarkable. Funduscopy revealed pallid edema of the right optic disc and a crowded, but unaffected, left optic disc (Figure 1A,B). Review of the CTA images revealed tapering of the angiographic signal in the right ICA, consistent with dissection (Figure 1C–E). The patient was started on continuous intravenous heparin, transitioned to enoxaparin, and then to warfarin. Atorvastatin and a smoking cessation program were initiated.

Figure 1: Initial presentation of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy secondary to internal carotid artery (ICA) dissection.

A, Color fundus photograph of the right eye show pallid optic nerve edema, most prominent nasally. B, Color fundus photograph of the left eye demonstrate a crowded disc. C-E, computed tomography angiography images in coronal (C), sagittal (D), and axial (E) planes. Coronal and sagittal views demonstrate a tapering of the angiographic signal within the right internal carotid artery (orange arrows), and the axial view shows crescentic narrowing the angiographic signal within the ICA lumen (red arrow) representing thrombus within the false lumen.

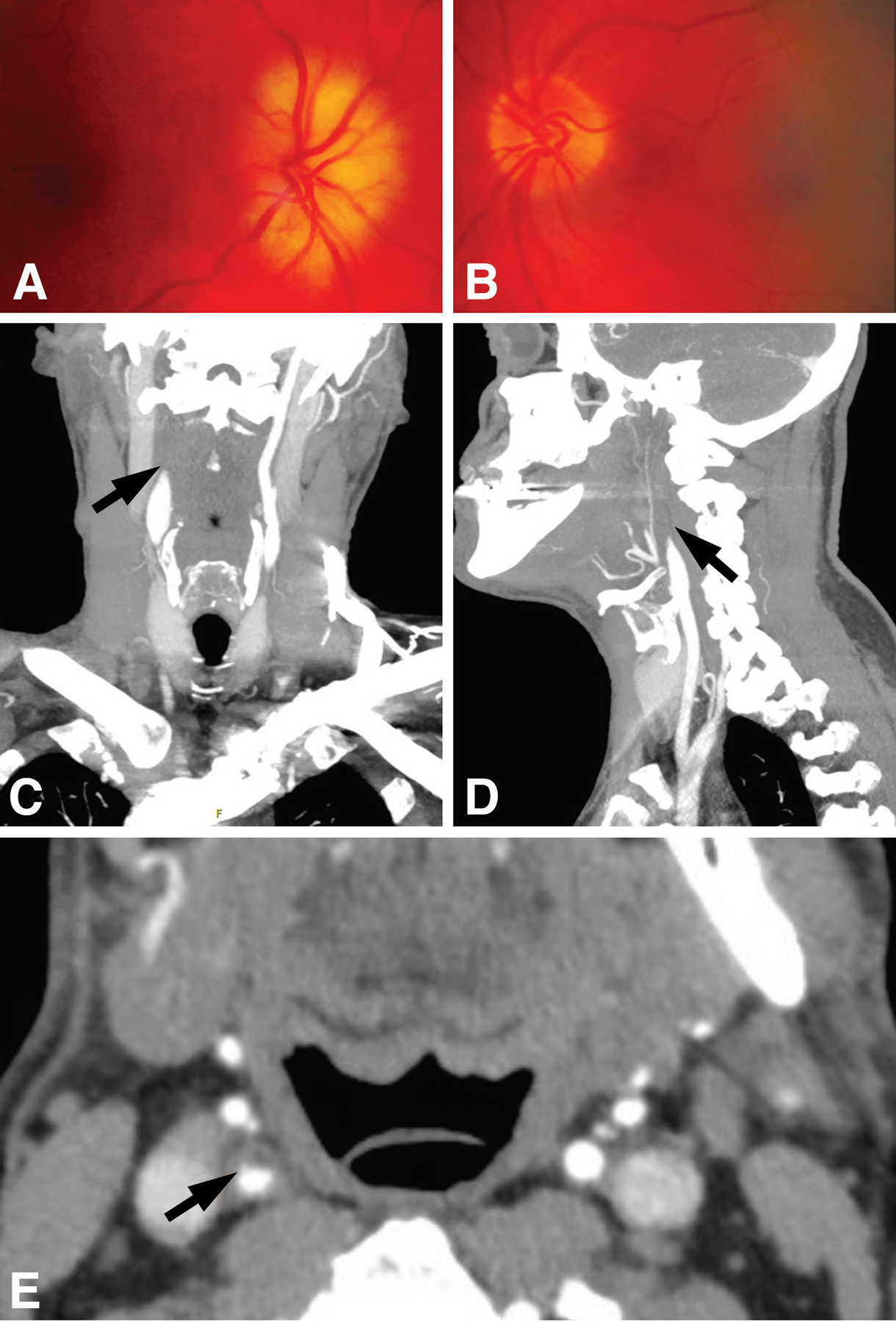

At one-month follow-up, visual acuity had improved to 20/30 OD and the optic disc edema had resolved yielding pallor (Figure 2A,B). Between 1 and 18 months follow-up, his visual field remained severely constricted in the right eye and normal in the left (Figure 2C,D).

Figure 2: Follow-up fundus photography and perimetry.

A, Color fundus photograph obtained 1-month after initial presentation of the right eye demonstrates resolution of optic nerve edema and pallor that spares the inferotemporal sector. B, Color fundus photograph of the left eye demonstrates an unchanged crowded optic disc. C-D, Automated perimetry (Humphrey SITA 30-2) performed 6 months after initial presentation shows severe constriction in the right eye with a superior island of relatively preserved field (C) and normal responses in the left eye (D). Pattern standard deviation plots (left) and gray scale plots (right) are depicted.

Internal carotid artery dissection (ICAD) is a common cause of ischemic stroke in young adults1, but the spectrum of ophthalmologic manifestations of ICAD is often underappreciated2. Painful anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) without clinical evidence of Horner syndrome was the presenting sign of ICAD in this case. Few cases of AION secondary to ICAD have been reported, with an estimated prevalence of 1.8% among patients with ICAD2,3. Early recognition of ICAD is imperative. While evidence to support immediate antithrombotic treatment is lacking, this approach is routine given the high risk of recurrent stroke4.

This entity may go unrecognized as neuroimaging is typically not performed in the setting of AION5. The presence and character of the pain was an important clue of this rare cause of AION, and the intense, radiating nature was notably distinct from the dull ache exacerbated by eye movement that is characteristic of inflammatory optic neuropathy6. Transient monocular blindness followed by improvement is also atypical for non-arteritic AION, but has been described in other cases of AION secondary to ICAD5, and likely reflects relatively severe ischemia signified by pallid edema. Pallid edema (Figure 1A) is also a feature distinct from nonarteritic AION, akin to that seen in arteritic AION and hemodialysis-associated AION6. The presence of a “disc at risk” in the fellow eye (Figure 1B) is also notable; this well-characterized risk factor (arguably requisite) for nonarteritic AION6 has been postulated to apply to AION in ICAD5. The findings in this particular case are consistent with the hypothesis that this common anatomic predisposition is important for the clinical manifestation of AION in the setting of ICAD.

Albeit rare, ICAD should be included in the differential for painful AION, and early recognition is critical. Further studies may provide valuable insight into the pathogenesis of more common forms of AION.

Funding:

EDG: NIH K08 EY030164

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors report no conflicts relevant to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Debette S, Leys D. Cervical-artery dissections: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and outcome. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(7):668–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biousse V, Touboul PJ, D’Anglejan-Chatillon J, Lévy C, Schaison M, Bousser MG. Ophthalmologic manifestations of internal carotid artery dissection. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126(4):565–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mokri B, Silbert PL, Schievink WI, Piepgras DG. Cranial nerve palsy in spontaneous dissection of the extracranial internal carotid artery. Neurology. 1996;46(2):356–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markus HS, Levi C, King A, Madigan J, Norris J, Cervical Artery Dissection in Stroke Study (CADISS) Investigators. Antiplatelet Therapy vs Anticoagulation Therapy in Cervical Artery Dissection: The Cervical Artery Dissection in Stroke Study (CADISS) Randomized Clinical Trial Final Results. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(6):657–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biousse V, Schaison M, Touboul PJ, D’Anglejan-Chatillon J, Bousser MG. Ischemic optic neuropathy associated with internal carotid artery dissection. Arch Neurol. 1998;55(5):715–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaier ED, Torun N. The enigma of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: an update for the comprehensive ophthalmologist. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2016;27(6):498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]