Abstract

Syngas, which contains large amount of CO2 as well as H2 and CO, can be convert to acetic acid chemically or biologically. Nowadays, acetic acid become a cost-effective nonfood-based carbon source for value-added biochemical production. In this study, acetic acid and CO2 were used as substrates for the biosynthesis of 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP) in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli carrying heterogeneous acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Acc) from Corynebacterium glutamicum and codon-optimized malonyl-CoA reductase (MCR) from Chloroflexus aurantiacus. Strategies of metabolic engineering included promoting glyoxylate shunt pathway, inhibiting fatty acid synthesis, dynamic regulating of TCA cycle, and enhancing the assimilation of acetic acid. The engineered strain LNY07(M*DA) accumulated 15.8 g/L of 3-HP with the yield of 0.71 g/g in 48 h by whole-cell biocatalysis. Then, syngas-derived acetic acid was used as substrate instead of pure acetic acid. The concentration of 3-HP reached 11.2 g/L with the yield of 0.55 g/g in LNY07(M*DA). The results could potentially contribute to the future development of an industrial bioprocess of 3-HP production from syngas-derived acetic acid.

Keywords: Syngas-derived acetic acid, 3-Hydroxypropionic acid, Metabolic engineering, Escherichia coli, Dynamic regulation

1. Introduction

The rising concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2), mainly due to the accelerated consumption of fossil fuels and other human activities, has caused an increase in global temperatures [[1], [2], [3]]. With such environmental concerns, there is growing interest focusing on upgrading CO2 waste into metabolites of interest through biotransformation pathways [4,5]. In order to reduce waste carbon streams emissions and transform them into value-added chemicals, the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Fossil Energy has selected eleven projects, which received about seventeen million dollars from federal funding, to utilize CO2 from various industrial processes as the mainly carbon source [6]. Bio-based synthesis of platform chemicals from low-cost and abundant feedstock has become more and more important with the gradual depletion of fossil fuels, the associated increasing feedstock costs and the rapid development of modern industry [7]. In the previous studies, acetic acid can be derived from the conversion of various one-carbon gases (CO, CO2, etc.) via microbial fermentation or electrosynthesis [[8], [9], [10]]. As a non-food based substrate, acetic acid is regarded as a quite promising carbon source instead of sugars, and there have been many studies on utilization and transformation of acetic acid into various value-added products such as succinate [11], itaconic acid [12], fatty acid [13], isopropanol [14], and so on.

3-Hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP), which is composed of two functional groups (carboxylic and hydroxyl) and can be easily transformed into other compounds (e.g., acrylic acid, acrylamide, 1,3-propanediol (PDO), and methacrylic acid) [15], is a widely used agent for organic synthesis [16]. Variety of metabolic pathways and microbes have been explored for 3-HP production, including malonyl-CoA pathway in Pseudomonas denitrificans [17], CoA-independent pathway in Klebsiella pneumoniae [18], β-alanine pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [19], malonyl-CoA pathway in Escherichia coli [20], and many other autotrophic or heterotrophic routes [21]. Among these processes, research on 3-HP production via malonyl-CoA route has been carried out in different chassis microorganisms model organisms, such as E. coli [22], S. cerevisiae [23], and Schizosaccharomyces pombe [24]. Production of 3-HP through malonyl-CoA route, is suitable for most carbon sources, including acetic acid, due to the malonyl-CoA is a universal intermediate in cell metabolism [20].

Although acetic acid can be utilized by many microorganisms, its consumption rate is much slower than those of sugar utilization, and reduced cell growth is also showed [25,26]. In E. coli, the acetic acid can be firstly converted to acetyl-CoA via two pathways, which were catalyzed by acetic acid kinase-phosphotransacetylase (AckA-Pta) or acetyl-CoA synthetase (Acs) (Fig. 1) [27]. Acetyl-CoA is then converted to malonyl-CoA with CO2 fixation catalyzed by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Acc). Since the majority of cellular malonyl-CoA is usually consumed to produce fatty acids [28], leaving only a small amount available for 3-HP production. Then, malonyl-CoA reductase (Mcr) was applied to redirect the malonyl-CoA flux away from fatty acid to 3-HP formation [20]. Furthermore, the biosynthesis of 3-HP from malonyl-CoA, catalyzed by Mcr, requires 2 mol of NAPDH [17,29,30].

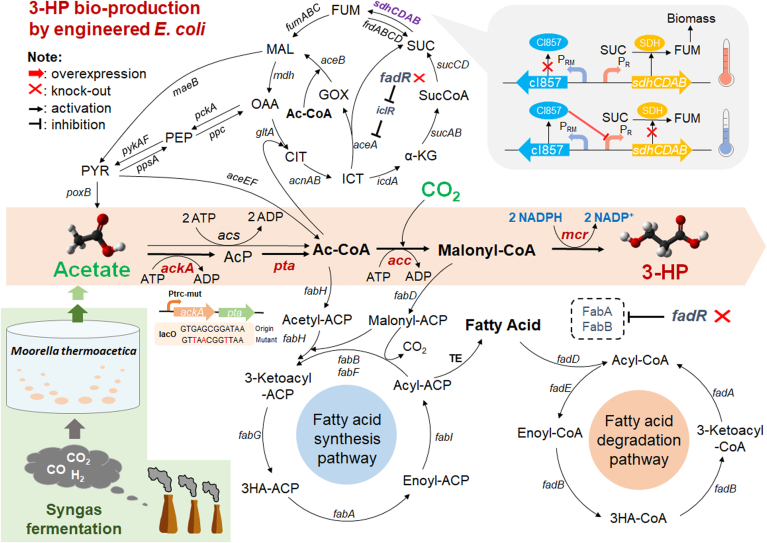

Fig. 1.

Simplified metabolic pathways of 3-HP biosynthesis by engineered E. coli strain using acetic acid as carbon source under aerobic condition. AcP, acetyl-phosphate; Ac-CoA, Acetyl-CoA; 3-HP, 3-hydroxypropionic acid; CIT, citrate; ICT, isocitrate, GOX, glyoxylate; α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; SucCoA, succinyl-CoA; SUC, succinate; FUM, fumarate; MAL, malate; OAA, oxaloacetate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PYR, pyruvate. ackA, acetate kinase; pta, phosphotransacetylase; acs, acetyl-CoA synthetase; acc, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; mcr, malonyl-CoA reductase; gltA, citrate synthase; aceA, isocitrate lyase; aceB, malate synthase; icdA: isocitrate dehydrogenase; sucAB, α ketoglutarate dehydrogenase; sucCD, succinyl-CoA synthetase; sdhABCD, succinate dehydrogenase; frdABCD, fumarate reductase; fumABC, fumarase; mdh, malate dehydrogenase; maeB, NADP-dependent malic enzyme; pckA, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; ppc phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; ppsA, phosphoenolpyruvate synthase; poxB, pyruvate oxidase; pykAF, pyruvate kinase; aceEF, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; iclR, isocitrate lyase regulator; fabA, beta-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratase/isomerase; fabB, beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase; fadR, fatty acid degradation repressor; Ptrc-mut, modified trc promoter.

In this work, a metabolic engineered E. coli carrying codon-optimized Mcr (N940V, K1106W and S1114R) from C. aurantiacus and Acc from Corynebacterium glutamicum was constructed to produce 3-HP via malonyl-CoA [20]. And to further increase 3-HP production, several engineering strategies were applied, including promoting glyoxylate shunt pathway by deletion of fadR, inhibiting fatty acid synthesis by overexpression of the native fabR, dynamic regulating of TCA cycle by controlling the expression of sdh. Finally, the utilization pathway of acetic acid was enhanced by replacing the promoter of ackA-pta. In this study, syngas-derived acetic acid, which was produced by the syngas fermentation of Moorella thermoacetica, was also used as the sole carbon source for 3-HP production by engineered E. coli strain. The titer and yield of 3-HP were similar as those of using chemically synthesized acetic acid as carbon source. The results indicated that the engineering system has high efficiency for the biosynthesis of 3-HP from syngas-derived acetic acid with CO2 fixation.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Strains and plasmids construction

All the bacterial strains and plasmids used in the experiments are described in Table 1, and all the primers used for amplification of different genes are listed in Table 2. The temperature-sensitive PR promoter including repressor protein CI857, amplifying by PCR using pCP20 as template, was subtiluted for the native promoter of sdh. The native promotor of ackA-pta in strain BL27 was replaced by the modified trc promotor (Ptrc-mut, Table 2) [31]. Deletion of fadR gene and replacement of native promoter of sdh or ackA-pta based on E. coli BL27 were created using the one-step inactivation method [32]. For the fadR gene deletion, the kanamycin resistance cassette flanked by FRT was amplified from pKD4 using primers with homologous arm for homologous recombination.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains/plasmids |

Description |

Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Moorella thermoacetica | acetogenic bacterium | [33] |

| BL27 | MG1655 F-lambda-ilvG-rfb-50 rph-1 ΔhsdR ΔampC lacZ∷T7 | From Prof Quan |

| LNY01 | BL27 Ptrc-mut-ackA-pta | This study |

| LNY02 | BL27 ΔfadR | This study |

| LNY03 | BL27 PR-sdh | This study |

| LNY04 | BL27 Ptrc-mut-ackA-pta ΔfadR | This study |

| LNY05 | BL27 Ptrc-mut-ackA-pta PR-sdh | This study |

| LNY06 | BL27 ΔfadR PR-sdh | This study |

| LNY07 | BL27 Ptrc-mut-ackA-pta ΔfadR PR-sdh | This study |

| BL27 (MDA) | BL27 containing pET28a-MDA | This study |

| BL27 (M*DA) | BL27 containing pET28a-M*DA | This study |

| LNY01(M*DA) | LNY01 containing pET28a-M*DA | This study |

| LNY02(M*DA) | LNY02 containing pET28a-M*DA | This study |

| LNY03(M*DA) | LNY03 containing pET28a-M*DA | This study |

| LNY04(M*DA) | LNY04 containing pET28a-M*DA | This study |

| LNY05(M*DA) | LNY05 containing pET28a-M*DA | This study |

| LNY06(M*DA) | LNY06 containing pET28a-M*DA | This study |

| LNY07(M*DA) | LNY07 containing pET28a-M*DA | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKD4 | oriR6Kγ, KmR, rgnB (Ter) | [32] |

| pKD46 | araBp-gam-bet-exo, bla (ApR), repA101 (ts), oriR101 | [32] |

| pCP20 | ApR, CmR, FLP recombinance | [32] |

| pBAD33 | Cloning vector, CmR, pACYC18 origin vector | Lab collection |

| pET28a-mcr-mut | KanR, pET-28a containing mutated mcr (N940V, K1106W and S1114R) gene from C.aurantiacus | This study |

| pET28a-M*DA | KanR, pET-28a containing codon-optimized mcr (N940V, K1106W and S1114R) gene from C.aurantiacus, dtsR1 and accBC genes from C.glutamicum | This study |

| pET28a-MDA | KanR, pET-28a containing codon-optimized mcr gene from C.aurantiacus, dtsR1 and accBC genes from C.glutamicum | [38] |

Table 2.

Primers and promoters used in this study.

| Primers/promoters |

Sequence (5’ - 3’) |

|---|---|

| Primers | |

| F-delta-fadR | TCTGGTATGATGAGTCCAACTTTGTTTTGCTGTGTTATGGAAATCTCACTCGTCTTGAGCGATTGTGTAG |

| R-delta-fadR | AACAACAAAAAACCCCTCGTTTGAGGGGTTTGCTCTTTAAACGGAAGGGAGATGTAACGCACTGAGAAGC |

| F-Ptrc-ack-pta-check | AGTGCATGATGTTAATCATAAATGTCGGTGTCATCATGCGCTACGCTCTAGGCCTTTCTGCTGTAGGCTGG |

| R-Ptrc-ack-pta-check | TTCAGAACCAGTACTAACTTACTCGACATGGAAGTACCTATAATTGATACGGTCTGTTTCCTGTGTGAAAT |

| F–N940V(K1106W) | GTTTATTATCTGGCGGATCGCGTGGTTTCCGGCGAAACC |

| R–N940V(K1106W) | GCCATCAGACAGCGCAATCCAGCGCGCTACGCGAAAATG |

| F–S1114R | GCGCTGTCTGATGGCGCGCGTCTGGCGCTGGTAACC |

| R–S1114R | TTAAACGGTAATCGCGCGGCCGCGATGAATG |

| F-mcr-mut | ATCCGAATTCGAGCTCATGTCTGGTACCGGT |

| R-mcr-mut | GGTTTCGCCGGAAACCACGCGATCCGCCAGATAATAAAC |

| F-accBC | AAGGATCCGTGTCAGTCGAGACTAGGAA |

| R-accBC | GCAAGCTTTTACTTGATCTCGAGGAGAA |

| F-dtsR1 | GCGCTAGCATGACCATTTCCTCACCTTT |

| R-dtsR1 | ATGGATCCTTACAGTGGCATGTTGCCGT |

| Promoters | |

| trc | TGTTGACAATTAATCATCCGGCTCGTATAATGTGTGGAATTGTGAGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGGAAACAGACC |

| Ptrc-mut | TGTTGACAATTAATCATCCGGCTCGTATAATGTGTGGAATTGTTAACGGTTAACAATTTCACACAGGAAACAGACC |

The mcr gene from C. aurantiacus was codon-optimized and synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd.. To obtain the mutated mcr (N940V, K1106W and S1114R), three fragments was cloned from codon-optimized mcr by PCR with primers F-mcr-mut/R-mcr-mut, F–N940V(K1106W)/R–N940V(K1106W), and F–S1114R/R–S1114R respectively. These three fragments were combined by overlap PCR with primers F-mcr-mut/R–S1114R. Gene segments of dtsR1 and accBC from C. glutamicum were amplified by PCR and then overlapped together to form dstR1-accBC. The ribosome binding sequence (AAGGAGATATACC) was added before the start codons of accBC and dtsR1 respectively. The mutated mcr gene was ligated to linear vector pET28a which was digested by SacI and SalI, yielding plasmid pET28a-mcr-mut. Then, the DNA fragments dstR1-accBC was inserted into pET28a-mcr-mut to form the plasmid pET28a-mcr-mut-dstR1-accBC (named as pET28a-M*DA).

2.2. Culture medium and conditions

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (per liter: 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 10 g sodium chloride) was used for strains construction and plasmids amplification. During strain and plasmid construction, the strains with the temperature-sensitive plasmids pKD46 and pCP20 were incubated at 30 °C or 42 °C, other strains were usually grown at 37 °C.

For fermentation in flasks, a single colony from the freshly grown plate was inoculated into 3 mL of LB media and cultured at 37 °C and 220 rpm for 8 h 500 μL of the preculture was added to 50 mL of LB media in a 250-mL flask, in which the cells were incubated under the same conditions for 8 h. For shake flask fermentation, the secondary preculture was inoculated (2% v/v) into a 250- mL flask containing 50 mL of fermentation medium and incubated at 37 °C (when the native promoter of sdh is replaced with the temperature-sensitive promoter, the culture temperature was 39 °C) and 220 rpm until induction. The fermentation medium was prepared by supplementing the minimal M9 medium with 10 g/L of ammonium acetate and 5 g/L of yeast extract. The minimal M9 medium contained (per liter): 40 mg biotin, 15.1 g Na2HPO4·12H2O, 3.0 g KH2PO4, 0.5 g NaCl, 1.0 g NH4Cl, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O, 0.011 g CaCl2, and 0.2 mL of 1% (w/v) vitamin B1. The appropriate antibiotics were included at the following concentrations: 50 μg/mL kanamycin, 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol, and 100 μg/mL ampicillin. When the OD600 reached around 1.0 or 2.5 due to different experiments, Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was provided at a final concentration of 0.1 mM for inducing the overexpression of MCR and Acc. Cultures subsequently were incubated at 25 °C for 3-HP production. The pH was maintained at about 7.0 by the addition of an appropriate amount of 3 M H2SO4 solution. All experiments had 3 biological replicates.

2.3. Syngas-derived acetic acid from biological culture broth

The biological culture broth of syngas-derived acetic acid was obtained from M. thermoacetica (ATCC 49707) strain, which converted a gas mixture of CO2 and CO or H2 into acetic acid in an anaerobic bioreactor [33].

The anaerobic acetogen M. thermoacetica, was cultivated at 60 °C under strict anaerobic conditions in an enhanced culture medium containing the following components (per liter): 10 g morpholino ethane sulfonic acid (MES), 10 g Yeast Extract, 1.4g KH2PO4, 1.1 g K2HPO4, 2.0 g (NH4)2SO4, 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O, 20 mL ATCC 1754 PETC trace elements solution (http://www.atcc.org), 10 mL of 0.3% cysteine solution, and 0.5 mL of 0.2% resazurin (a color indicator for anaerobic conditions).

The 1-L glass bubble column reactor was used for cultivation of M. thermoacetica. Throughout the fermentation process, gas composition of CO/H2/CO2 (4/3/3) was maintained constant with a four-channel mass flow controller and pH was controlled at around 6 by addition of 5 N NaOH or HCl. Prepared media (excluding cysteine), sterilized and then added into the reactor, was purged with oxygen-free nitrogen overnight. The cells were grown on syngas mixture with a total gas flow rate of 100 sccm (standard cubic centimeters per minute). A cysteine solution was added to remove dissolved oxygen in the medium for anaerobic growth conditions, and the bioreactor was inoculated with 5% v/v.

2.4. Whole-cell bioconversion for 3-HP production

The whole-cell fermentation experiments were performed using the concentrated genetically engineered E. coli strain LNY07(M*DA). In the whole-cell bioconversion experiments (40 OD600), the preculture and culture conditions were the same as that of the previous shake-flask fermentation. The cells were harvested after 25 h cultivation (mid-log phase of growth) by centrifugation at 5500 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min, washed once with M9 medium and resuspended in 50 mL of the same medium supplemented with 20 g/L ammonium acetate or biological culture broth containing syngas-derived acetic acid. The flasks were incubated at 25 °C and 220 rpm. The pH was maintained at 7.0 using 3 M H2SO4.

2.5. Analytical methods

Growth was monitored by using a UV–visible spectroscopy system (Xinmao, Shanghai, China) at OD600. Acetic acid and 3-HP were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) at 50 °C on an Aminex HPX-87H column (300 × 7.8 mm, Bio-Rad, USA) as well as a refractive index detector (RID) (Agilent, USA). A mobile phase of 2.5 mM H2SO4 solution was used at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. All culture samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min and then filtered through a 0.22-μm filter before analysis.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of push-and-pull strategy on 3-HP accumulation

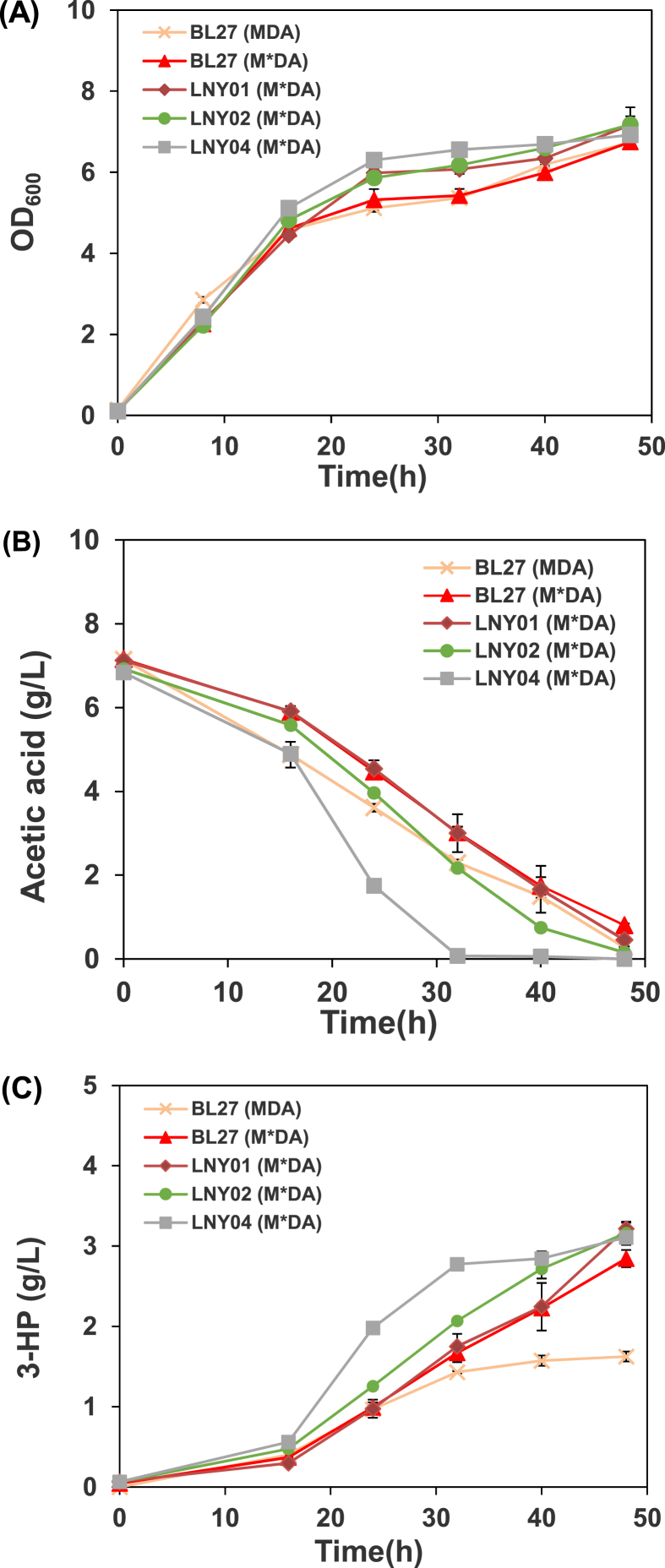

The push-and-pull strategy for metabolic engineering was applied in this study. As mentioned previously, there are generally two pathways to deplete acetic acid in E. coli, AckA-Pta pathway and Acs pathway [31,34]. Both pathways can convert acetic acid to acetyl-CoA, but there are obvious differences between these two pathways. The AckA-Pta pathway was discovered to be central for mutual conversion between acetic acid and acetyl-CoA [27]. The direction of reaction in this pathway can be rapidly transformed from acetic acid production to acetic acid consumption [35], which is a major pathway for acetic acid assimilation. In contrast, Acs pathway is responsible only for conversion acetic acid to acetyl-CoA. For acetic acid uptake, the former pathway consumes less energy than the latter because Acs in E. coli consumes ATP and produces AMP instead of ADP [36]. Mutant cells lacking AckA-Pta pathway grew poorly in high concentrations of acetic acid [37]. Previous studies have shown that when high concentrations of acetic acid is used as carbon source, the AckA-Pta pathway is the main route for acetic acid assimilation [31,34]. In previous study, the plasmid pET28a-MDA has been proven enough to produce 3-HP at high concentration from glucose [38]. We constructed the pET28a-M*DA (MCR with 3 mutations: N940V, K1106W, and S114R) on the basis of pET28a-MDA, since the MCR with 3 mutations (N940V, K1106W, and S114R) performed much better than MCR in the production of 3-HP from glucose [20]. Compared with BL27 (MDA), BL27 (M*DA) achieved a higher 3-HP production (~1.75-fold more) and yield on acetic acid (0.44 g/g vs. 0.23 g/g) (Fig. 2, Fig. 5). It indicated that the mutant of MCR can still maintain the higher activity in the cultivation of acetic acid as well as glucose. When 5 g/L yeast extract was added to the minimal M9 medium without adding acetic acid, only a small amount of 3-HP was detected, about 0.1 g/L (Data not shown). Therefore, it could be considered that yeast extract is mostly used for the growth of E. coli, and acetic acid is the main carbon source for the production of 3-HP. In order to enhance acetic acid utilization and improve 3-HP production in our engineering strains, the native promoter shared by ackA and pta genes in the strain E. coli BL27 was replaced to a modified trc promoter (Ptrc-mut, Table 2), yielding strain LNY01. The strain LNY01(M*DA) produced 3.22 g/L of 3-HP in 48 h, about 13.0% higher than that of BL27 (M*DA) (Fig. 2A and B). And the yield of 3-HP in LNY01 (M*DA) reached 0.472 g/g, which is about 8.0% higher than that of the control strain. The results indicated that promoting the acetic acid up-take rate was beneficial for the 3-HP production.

Fig. 2.

Profiles of cell density (A), acetic acid concentration (B), 3-HP concentration (C) and yield of 3-HP (D) in cultivation of different strains: BL27 (MDA), BL27 (M*DA), LNY01(M*DA), LNY02(M*DA), and LNY04(M*DA).

Fig. 5.

The 3-HP yield of different engineered strains.

When E. coli grows on acetic acid as a sole carbon source, the glyoxylate cycle is a critical and up-regulated, which can replenish dicarboxylic acid intermediates from the TCA cycle for cell metabolism and increase the utilization rate of exogenous acetic acid [39]. In the pathway, isocitrate is cleaved by isocitrate lyase (encoded by aceBAK) to succinate and glyoxylate (Fig. 1) [40]. IclR (isocitrate lyase repressor, encoded by iclR) is known as a repressor protein binding to a site which overlaps the aceBAK promoter [41]. Thus, the most common approach to enhance the glyoxylate cycle is deletion of iclR. FadR (fatty acid degradation repressor) is recognized as a fatty acid metabolism regulator, which not only represses fatty acid degradation pathway [42,43], but also activates expression of genes essential for the unsaturated fatty acid synthesis [44]. Additionally, it has been reported that FadR activates the expression of iclR by binding to a part of the upstream site of the iclR promoter [41]. In this work, we investigated the effect of deletion of fadR on 3-HP production. The fadR gene was deleted in E. coli BL27 strain, resulting in LNY02 strain. And the plasmid pET28a-M*DA was inserted into LNY02 to obtain the LNY02(M*DA) strain. It was found that the cell biomass of strain LNY02(M*DA) were enhanced (Fig. 2A), and the 3-HP production and acetic acid assimilation rate were also higher than that of strain BL27 (M*DA) (Fig. 2B and C). LNY02(M*DA) produced 3.16 g/L 3-HP, which was 10.9% higher than that of BL27 (M*DA). In addition, the yield of 3-HP on acetic acid (0.46 g/g) was increased slightly due to the increased substrate consumption and product accumulation. The consumption rate of acetic acid was significantly increased by combining with “push” (enhancing the pathway of acetic acid uptake by overexpression of ackA-pta) and “pull” (enhancing the pathway of acetic acid utilization by deletion of fadR). Between 16 and 32 h, the acetic acid consumption rate of strain LNY04(M*DA) reached 0.3 g/L/h, which was a 68% increase compared to BL27 (M*DA). The results demonstrated that the deletion of fadR shown a positive effect on the 3-HP production and yield.

Although the cell growth, 3-HP production, and acetic acid uptake rate were successfully enhanced, the yield was still low. The native promoter of ackA and pta in LNY02 was further replaced, yielding the LNY04 strain. Compared to BL27 (M*DA), LNY04(M*DA) showed improved 3-HP titer by 9.1% (from 2.85 to 3.11 g/L) in 48 h cultivation (Fig. 2A and C). In addition, all acetic acid had been consumed by the strain LNY04(M*DA) in 32 h (Fig. 2B), and the 3-HP production rate of LNY04(M*DA) was also enhanced significantly (Fig. 2C). It indicated the strain has great potential to convert acetic acid into 3-HP.

3.2. Effect of temperature-controlled TCA cycle on 3-HP accumulation

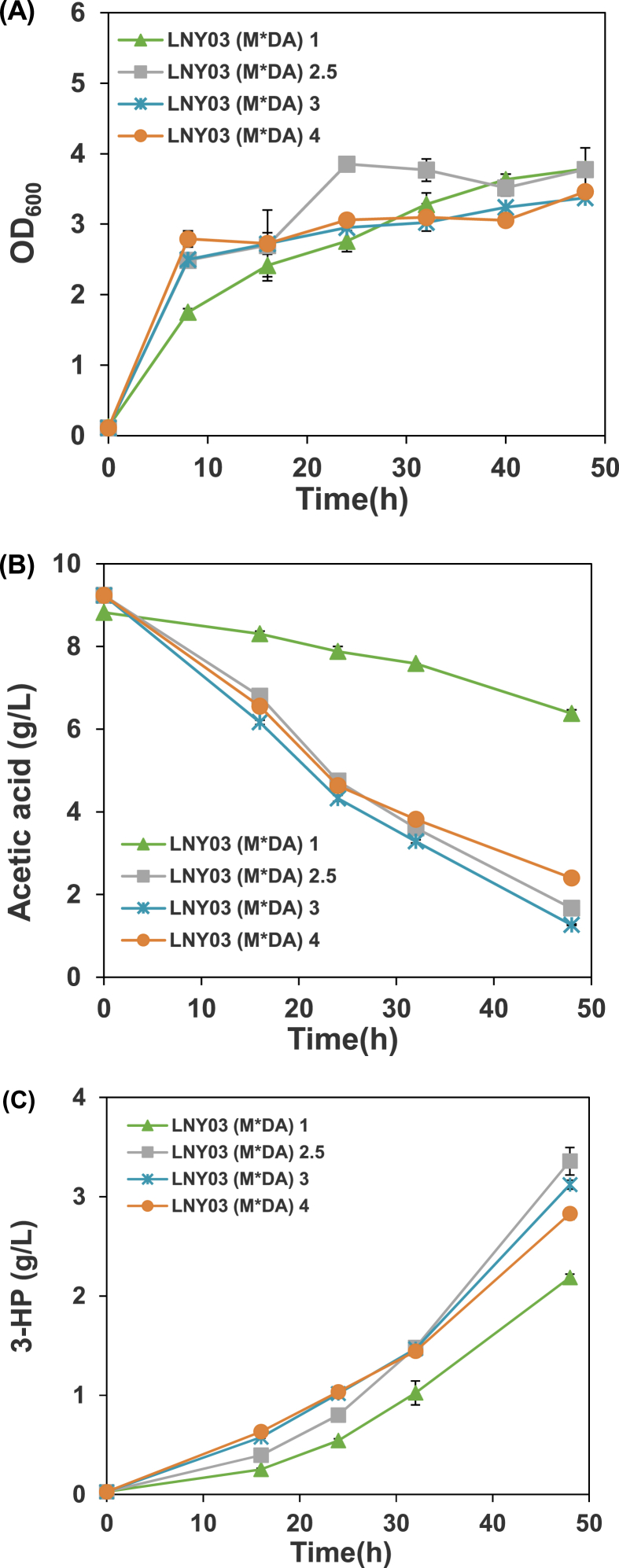

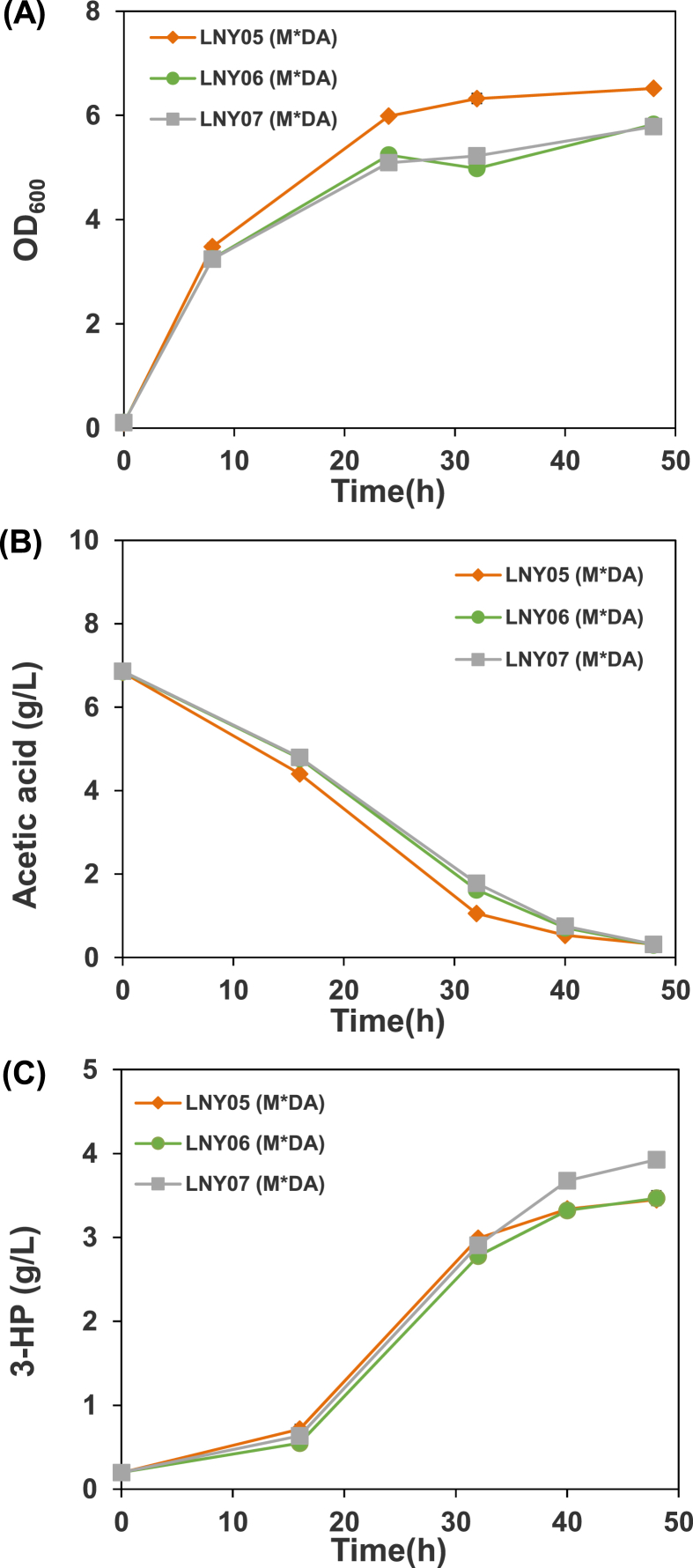

To further regulate the carbon flux and improve 3-HP accumulation, we decided to dynamically regulate TCA cycle by controlling the expression of sdh. The bacteriophage λ promoters (PR, PL) enable a simple temperature change to switch on-off the expression of genes efficiently and rapidly by using the temperature-sensitive repressor CI857 [45,46]. In a previous study, the native lactate dehydrogenase gene (ldhA) in E. coli were controlled by the promoters, which repressed ldhA when growth at 33 °C and was able to increase the biomass yield by 10% (compared with the static strategy), while switching to 42 °C induced the expression of ldhA and increased the production of lactate [45]. In our case, sdh is active under the control of the PR promoter during cell growth (favored by an inactive CI857 at 39 °C) and inactive due to CI857 is active at low temperatures and binds to the PR promoter in the phase of 3-HP production (favored by an active CI857 at 25 °C). Through the dynamic regulation of sdh, we expect to decouple the growth and 3-HP production. We obtained LNY03, LNY05, LNY06 and LNY07 strains by changing the native promoter of sdh into the temperature-sensitive promoter PR in BL27, LNY01, LNY02 and LNY04 strain, respectively. As the native promoter is replaced, different OD600 of induction were studied in the strain LNY03(M*DA). When the OD600 of induction was 1, only 2.46 g/L of acetic acid was consumed, about 28% of the initial acetic acid with least 3-HP accumulation (Fig. 3). And when the OD600 of induction was 2.5, LNY03(M*DA) produced the highest concentration of 3-HP. The experimental results showed that the expression level of SDH affects carbon flux distribution and it was found that the optimum OD600 value for induction of the 3-HP biosynthesis pathway was 2.5 (Fig. 3). The strains LNY03(M*DA), LNY05(M*DA), LNY06(M*DA) and LNY07(M*DA) generated 3.48, 3.45, 3.46 and 3.92 g/L of 3-HP in 48 h (Fig. 3, Fig. 4B), which were 22.1, 7.2, 9.5 and 26.0% higher than those of the control strains without promoter exchanging. The yield of 3-HP in LNY07 (M*DA) reached 0.57 g/g, which is about 76% of theoretical maximum (0.75 g/g) (Fig. 5). The result showed that replacing the promoter of sdh with the temperature-sensitive promoter enhanced the rate of 3-HP production significantly.

Fig. 3.

Profiles of cell density (A), acetic acid concentration (B), 3-HP concentration (C) and yield of 3-HP (D) in cultivation of strain LNY03(M*DA) with different initial OD600 of induction: 1, 2.5, 3 and 4.

Fig. 4.

Profiles of cell density (A), acetic acid concentration (B), 3-HP concentration (C) and yield of 3-HP (D) in cultivation of different strains: LNY05(M*DA), LNY06(M*DA), and LNY07(M*DA).

3.3. The 3-HP production in whole-cell bioconversion of engineered E. coli strain

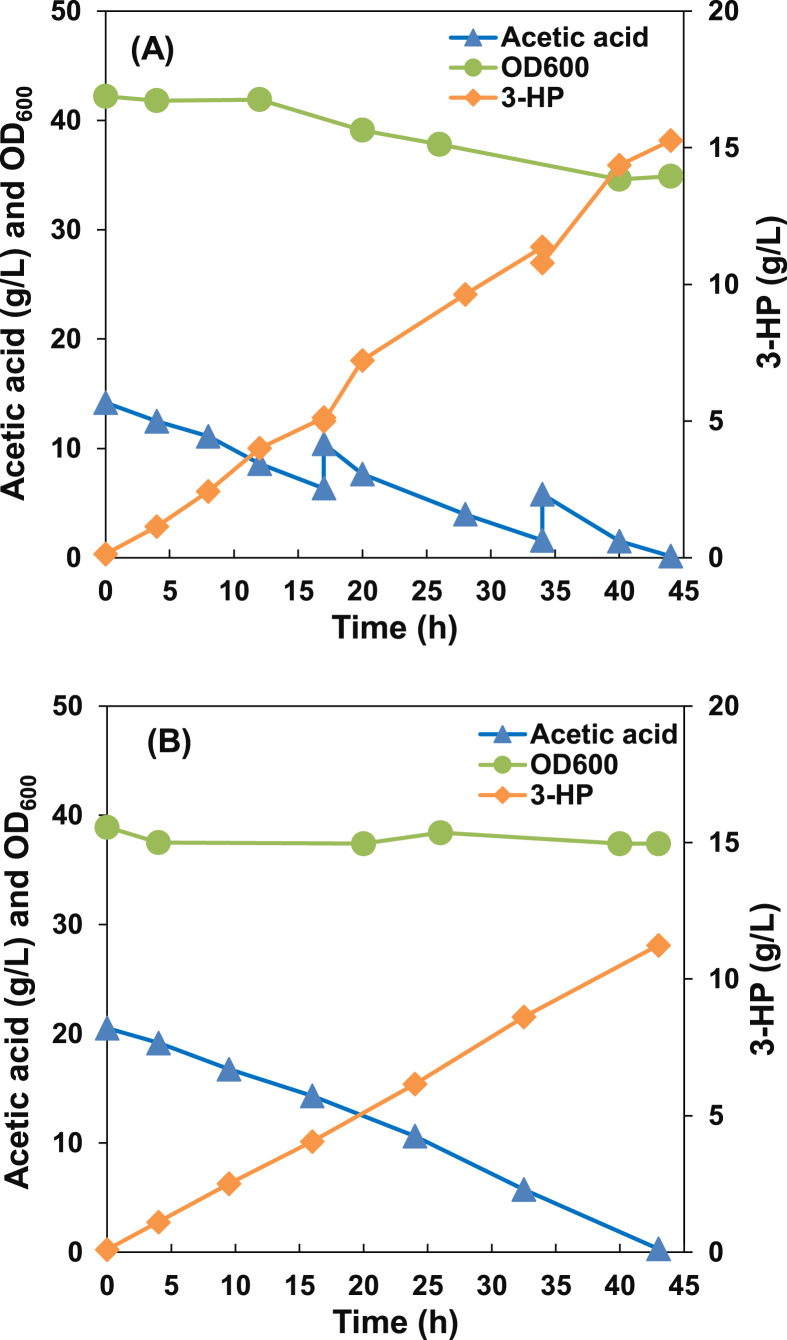

Whole-cell catalysis has the advantages of higher cell density, higher product yield and productivity, lower energy requirements, etc. In the experiment we used concentrated E. coli strain LNY07(M*DA), which had both a high titer and high yield of 3-HP as whole-cell biocatalyst, acetic acid as the sole carbon source. The initial OD600 of LNY07(M*DA) was around 40. After 44 h of bioconversion, almost all the acetic acid was consumed and 15.8 g/L 3-HP was obtained (Fig. 6A), with the yield increasing to 0.71 g/g, about 94% of the maximum theoretical pathway. The titer of 3-HP in the biotransformation was significantly higher than the concentration obtained using fed-batch cultures. The titer of 3-HP increased significantly due to the high cell density, and it indicated that the carbon metabolic flux were redirected into the 3-HP production pathway by whole-cell bioconversion. The cell density decreased during the process, which may occur due to the repeatedly addition of acetic acid (at 17 and 34 h) (Fig. 6A), which was to prolong the production of 3-HP and better test the life span of 3-HP production activity. And the production rate of 3-HP was maintained constantly during the cultivation, about 0.35 g/L/h.

Fig. 6.

Profiles of cell density, acetic acid and 3-HP concentrations in LNY07(M*DA) using whole-cell bioconversion of chemically synthesized acetic acid and syngas-derived acetic acid.

3.4. Utilization of syngas-derived acetic acid for 3-HP

Here, the syngas-derived acetic acid, which was produced by M. thermoacetica, was used as a solo carbon source for 3-HP biosynthesis by LNY07(M*DA). The results of acetic acid consumption, 3-HP production and cell density during the cultivation are shown in Fig. 6B. The initial concentration of acetic acid in the syngas fermentation broth was 20.5 g/L and the initial OD600 of LNY07(M*DA) was around 39. As a result, the strain consumed almost all the acetic acid in the biologically produced culture medium and accumulated 11.2 g/L 3-HP from the syngas-derived acetic acid. The titer of 3-HP dropped due to the initial concentration of acetic acid in the biologically produced culture medium. No additional acetic acid was added during the cultivation. In addition, the cell density did not show any significant decrease compared to the condition of using chemically synthesized acetic acid. The complex composition in the culture broth of M. thermoacetica may help the cell density. Since the yield of 3-HP dropped a little (0.55 g/g), it indicated that more acetic acid maybe used to the cell maintenance than that of using chemically synthesized acetic acid. In this study, the current titer of 3-HP from syngas-derived acetic acid was the highest concentration ever reported. This result indicates a great potential for the metabolically engineered E. coli strain to generate 3-HP from syngas-derived acetic acid.

The current results can be compared with other studies using E. coli as host to produce 3-HP from acetic acid. The engineered E. coli converted 8.98 g/L of acetic acid into 3.00 g/L of 3-HP in 48 h cultivation with overexpression of mcr and acs and deletion of iclR, when 50 μM cerulenin was added to repress fatty acid synthesis pathway [29]. In two-stage bioreactor (glucose is used for cell growth and acetic acid for 3-HP formation), the engineered E. coli strain with upregulated glyoxylate shunt produced 7.3 g/L of 3-HP with yield of 0.26 mol/mol (0.39 g/g) [30]. In comparison, the engineered E. coli LNY07(M*DA) obtained 15.8 g/L of 3-HP with the yield of 0.71 g/g from chemically synthesized acetic acid and 11.2 g/L of 3-HP with the yield of 0.55 g/g from syngas-derived acetic acid. The study demonstrates an effective route to produce 3-HP from acetic acid. Despite the encouraging results in the whole-cell bioconversion experiment, there are still challenges. Compared with the use of glucose as the substrate, when acetic acid is used as the substrate, the cell growth is slower and the final titer of 3-HP is lower. Studies have been conducted to balance the activities of key enzymes and use glucose to synthesize 40.6 g/L of 3-HP in E. coli [20]. In order to increase the production of 3-HP from acetic acid, further strain modification or bioprocess optimization should be considered.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the engineered E. coli strains can produce 3-HP using acetic acid efficiently. Several strategies were applied to enhance 3-HP production from acetic acid, including exchanging promoter of ackA-pta, deletion of fadR, and temperature-controlling the expression of sdh. The engineered strain LNY07(M*DA) produced 15.8 g/L of 3-HP with the yield of 0.71 g/g from chemically synthesized acetic acid and 11.2 g/L of 3-HP with the yield of 0.55 g/g from syngas-derived acetic acid. The results demonstrate an effective route to use syngas-derived acetic acid as raw materials to produce 3-HP and other important chemicals, especially malonyl-CoA derived compounds.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ningyu Lai: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Yuanchan Luo: Formal analysis. Peng Fei: Formal analysis. Peng Hu: Formal analysis. Hui Wu: Conceptualization, Supervision.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Shu Quan for kindly providing us with the strain, E. coli BL27. This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (19ZR1472700), the Fok Ying-Tong Education Foundation, China (Grant No. 161017), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21776083), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 22221818014). Partially supported by Open Funding Project of the CAS Key Laboratory of Synthetic Biology.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

References

- 1.Dibenedetto A., Nocito F. The future of carbon dioxide chemistry. ChemSusChem. 2020;13:1–11. doi: 10.1002/cssc.202002029. https://10.1002/cssc.202002029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen S., Wang G., Zhang M., Tang Y., Gu Y., Jiang W., Wang Y., Zhuang Y. Effect of temperature and surfactant on biomass growth and higher-alcohol production during syngas fermentation by Clostridium carboxidivorans P7. Bioresources and Bioprocessing. 2020;7:56. https://10.1186/s40643-020-00344-4 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burkart M.D., Hazari N., Tway C.L., Zeitler E.L. Opportunities and challenges for catalysis in carbon dioxide utilization. ACS Catal. 2019;9:7937–7956. https://10.1021/acscatal.9b02113 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H., Song T., Fei K., Wang H., Xie J. Microbial electrosynthesis of organic chemicals from CO2 by Clostridium scatologenes ATCC 25775T. Bioresources and Bioprocessing. 2018;5:7. https://10.1186/s40643-018-0195-7 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unrean P., Tee K.L., Wong T.S. Metabolic pathway analysis for in silico design of efficient autotrophic production of advanced biofuels. Bioresources and Bioprocessing. 2019;6:49. https://10.1186/s40643-019-0282-4 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xprt E. DOE invests $17 million to advance carbon utilization projects. https://www.energy-xprt.com/news/doe-invests-17-million-to-advance-carbon-utilization-projects-990539 [accessed October]

- 7.Fei Q., Chang H.N., Shang L., Choi J.-D.-R. Exploring low-cost carbon sources for microbial lipids production by fed-batch cultivation of Cryptococcus albidus. Biotechnol Bioproc Eng. 2011;16:482–487. https://10.1007/s12257-010-0370-y [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu P., Rismani-Yazdi H., Stephanopoulos G. Anaerobic CO2 fixation by the acetogenic bacterium Moorella thermoacetica. AIChE J. 2013;59:3176–3183. https://10.1002/aic.14127 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge X., Yang L., Sheets J.P., Yu Z., Li Y. Biological conversion of methane to liquid fuels: status and opportunities. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32:1460–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.09.004. https://10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song H., Choi O., Pandey A., Kim Y.G., Joo J.S., Sang B.-I. Simultaneous production of methane and acetate by thermophilic mixed culture from carbon dioxide in bioelectrochemical system. Bioresour Technol. 2019;281:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.02.115. https://10.1016/j.biortech.2019.02.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y., Huang B., Wu H., Li Z., Ye Q., Zhang Y.P. Production of succinate from acetate by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. ACS Synth Biol. 2016;5:1299–1307. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.6b00052. https://10.1021/acssynbio.6b00052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noh M.H., Lim H.G., Woo S.H., Song J., Jung G.Y. Production of itaconic acid from acetate by engineering acid-tolerant Escherichia coli W. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2018;115:729–738. doi: 10.1002/bit.26508. https://10.1002/bit.26508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao Y., Ruan Z., Liu Z., Wu S.G., Varman A.M., Liu Y., Tang Y.J. Engineering Escherichia coli to convert acetic acid to free fatty acids. Biochem Eng J. 2013;76:60–69. https://10.1016/j.bej.2013.04.013 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang H., Zhang C., Lai N., Huang B., Fei P., Ding D., Hu P., Gu Y., Wu H. Efficient isopropanol biosynthesis by engineered Escherichia coli using biologically produced acetate from syngas fermentation. Bioresour Technol. 2019;296:122337. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122337. https://10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Fouchécour F., Sánchez-Castañeda A.-K., Saulou-Bérion C., Spinnler H. Process engineering for microbial production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid. Biotechnol Adv. 2018;36:1207–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.03.020. https://10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gokarn R, Selifonova O, Jessen H, Gort S, Selmer T, Buckel W, US8198066 B2, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Zhou S., Lama S., Jiang J., Sankaranarayanan M., Park S. Use of acetate for the production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid by metabolically-engineered Pseudomonas denitrificans. Bioresour Technol. 2020;307:123194. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123194. https://10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y., Wang X., Ge X., Tian P. High production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid in Klebsiella pneumoniae by systematic optimization of glycerol metabolism. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26932. doi: 10.1038/srep26932. https://10.1038/srep26932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borodina I., Kildegaard K.R., Jensen N.B., Blicher T.H., Maury J., Sherstyk S., Schneider K., Lamosa P., Herrgard M.J., Rosenstand I., Oberg F., Forster J., Nielsen J. Establishing a synthetic pathway for high-level production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via beta-alanine. Metab Eng. 2015;27:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.10.003. https://10.1016/j.ymben.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C., Ding Y., Zhang R., Liu H., Xian M., Zhao G. Functional balance between enzymes in malonyl-CoA pathway for 3-hydroxypropionate biosynthesis. Metab Eng. 2016;34:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.01.001. https://10.1016/j.ymben.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lian H., Zeldes B.M., Lipscomb G.L., Hawkins A.B., Han Y., Loder A.J., Nishiyama D., Adams M.W., Kelly R.M. Ancillary contributions of heterologous biotin protein ligase and carbonic anhydrase for CO2 incorporation into 3-hydroxypropionate by metabolically engineered Pyrococcus furiosus. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113:2652–2660. doi: 10.1002/bit.26033. https://10.1002/bit.26033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu R., Liang L., Choudhury A., Bassalo M.C., Garst A.D., Tarasava K., Gill R.T. Iterative genome editing of Escherichia coli for 3-hydroxypropionic acid production. Metab Eng. 2018;47:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.04.007. https://10.1016/j.ymben.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C., Ding Y., Xian M., Liu M., Liu H., Ma Q., Zhao G. Malonyl-CoA pathway: a promising route for 3-hydroxypropionate biosynthesis. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2017;37:933–941. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2016.1272093. https://10.1080/07388551.2016.1272093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suyama A., Higuchi Y., Urushihara M., Maeda Y., Takegawa K. Production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid via the malonyl-CoA pathway using recombinant fission yeast strains. J Biosci Bioeng. 2017;124:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.04.015. https://10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Mey M., De Maeseneire S., Soetaert W., Vandamme E. Minimizing acetate formation in E. coli fermentations. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;34:689–700. doi: 10.1007/s10295-007-0244-2. https://10.1007/s10295-007-0244-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinhal S., Ropers D., Geiselmann J., De Jong H. Acetate metabolism and the inhibition of bacterial growth by acetate. J Bacteriol. 2019;201 doi: 10.1128/JB.00147-19. https://10.1128/jb.00147-19 e00147-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enjalbert B., Millard P., Dinclaux M., Portais J.C., Letisse F. Acetate fluxes in Escherichia coli are determined by the thermodynamic control of the Pta-AckA pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42135. doi: 10.1038/srep42135. https://10.1038/srep42135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu P., Gu Q., Wang W., Wong L., Bower A.G., Collins C.H., Koffas M.A. Modular optimization of multi-gene pathways for fatty acids production in E. coli. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1409. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2425. https://10.1038/ncomms2425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J.H., Cha S., Kang C.W., Lee G.M., Lim H.G., Jung G.Y. Efficient conversion of acetate to 3-hydroxypropionic acid by engineered Escherichia coli. Catalysts. 2018;8:10. https://10.3390/catal8110525 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lama S., Kim Y., Nguyen D.T., Im C.H., Sankaranarayanan M., Park S. Production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from acetate using metabolically-engineered and glucose-grown Escherichia coli. Bioresour Technol. 2021;320:124362. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.124362. https://10.1016/j.biortech.2020.124362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang B., Yang H., Fang G., Zhang X., Wu H. Central pathway engineering for enhanced succinate biosynthesis from acetate in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2018;115:943–954. doi: 10.1002/bit.26528. https://10.1002/bit.26528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Datsenko K.A., Wanner B.L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. https://10.1073/pnas.120163297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu P., Chakraborty S., Kumar A., Woolston B., Liu H., Emerson D., Stephanopoulos G. Integrated bioprocess for conversion of gaseous substrates to liquids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:3773–3778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516867113. https://10.1073/pnas.1516867113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Mets F., Van Melderen L., Gottesman S. Regulation of acetate metabolism and coordination with the TCA cycle via a processed small RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:1043–1052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815288116. https://10.1073/pnas.1815288116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim H.G., Lee J.H., Noh M.H., Jung G.Y. Rediscovering acetate metabolism: its potential sources and utilization for biobased transformation into value-added chemicals. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:3998–4006. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00458. https://10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Placzek S., Schomburg I., Chang A., Jeske L., Ulbrich M., Tillack J., Schomburg D. BRENDA in 2017: new perspectives and new tools in BRENDA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D380–D388. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw952. https://10.1093/nar/gkw952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown T.D., Jones-Mortimer M.C., Kornberg H.L. The enzymic interconversion of acetate and acetyl-coenzyme A in Escherichia coli. J Gen Microbiol. 1977;102:327–336. doi: 10.1099/00221287-102-2-327. https://10.1099/00221287-102-2-327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng Z., Jiang J., Wu H., Li Z., Ye Q. Enhanced production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from glucose via malonyl-CoA pathway by engineered Escherichia coli. Bioresour Technol. 2016;200:897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.107. https://10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maloy S.R., Nunn W.D. Role of gene fadR in Escherichia coli acetate metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:83–90. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.1.83-90.1981. https://10.1128/JB.148.1.83-90.1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang B., Wang P., Zheng E., Chen X., Zhao H., Song P., Su R., Li X., Zhu G. Biochemical properties and physiological roles of NADP-dependent malic enzyme in Escherichia coli. J Microbiol. 2011;49:797–802. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-0487-5. https://10.1007/s12275-011-0487-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gui L., Sunnarborg A., Laporte D.C. Regulated expression of a repressor protein: FadR activates iclR. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4704–4709. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4704-4709.1996. https://10.1128/jb.178.15.4704-4709.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clark D. Regulation of fatty acid degradation in Escherichia coli: analysis by operon fusion. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:521–526. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.2.521-526.1981. https://10.1128/JB.148.2.521-526.1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hughes K.T., Simons R.W., Nunn W.D. Regulation of fatty acid degradation in Escherichia coli: fadR superrepressor mutants are unable to utilize fatty acids as the sole carbon source. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1666–1671. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1666-1671.1988. https://10.1128/jb.170.4.1666-1671.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nunn W.D., Giffin K., Clark D., Cronan J.E., Jr. Role for fadR in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:554–560. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.554-560.1983. https://10.1128/JB.154.2.554-560.1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou L., Niu D.D., Tian K.M., Chen X.Z., Prior B.A., Shen W., Shi G.Y., Singh S., Wang Z.X. Genetically switched D-lactate production in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2012;14:560–568. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.05.004. https://10.1016/j.ymben.2012.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venayak N., Anesiadis N., Cluett W.R., Mahadevan R. Engineering metabolism through dynamic control. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015;34:142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.12.022. https://10.1016/j.copbio.2014.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]