Abstract

Purpose

The impact of the interval between previous endoscopy and diagnosis on the treatment modality or mortality of undifferentiated (UD)-type gastric cancer is unclear. This study aimed to investigate the effect of endoscopic screening interval on the stage, cancer-related mortality, and treatment methods of UD-type gastric cancer.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed the medical records of newly diagnosed patients with UD gastric cancer in 2013, in whom the interval between previous endoscopy and diagnosis could be determined. The patients were classified into different groups according to the period from the previous endoscopy to diagnosis (<12 months, 12–23 months, 24–35 months, ≥36 months, and no history of endoscopy), and the outcomes were compared between the groups. In addition, patients who underwent endoscopic and surgical treatment were reclassified based on the final treatment results.

Results

The number of enrolled patients was 440, with males representing 64.1% of the study population; 11.8% of the participants reported that they had undergone endoscopy for the first time in their cancer diagnosis. The percentage of stage I cancer at diagnosis significantly decreased as the interval from the previous endoscopy to diagnosis increased (65.4%, 63.2%, 64.2%, 45.9%, and 35.2% for intervals of <12 months, 12–23 months, 24–35 months, ≥36 months, and no previous endoscopy, respectively, P<0.01). Cancer-related mortality was significantly lower for a 3-year interval of endoscopy (P<0.001).

Conclusions

A 3-year interval of endoscopic screening reduces gastric-cancer-related mortality, particularly in cases of UD histology.

Keywords: Stomach neoplasms; Endoscopy, digestive system; Survival rate

INTRODUCTION

Gastric adenocarcinoma is classified into 4 types—tubular adenocarcinoma, papillary adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and signet ring cell carcinoma—according to the World Health Organization classification [1]. Among these, poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell carcinoma are grouped as undifferentiated (UD)-type gastric carcinoma according to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association [2].

Gastric cancer-related mortality is directly associated with the cancer stage; the 5-year survival rate of early gastric cancer (EGC) is over 90% [3,4,5]. However, UD-type gastric cancer is a risk factor for lymph node metastasis in EGC. It tends to invade the submucosal layer, leading to aggressive biological behavior and poorer prognosis with delayed diagnosis [2,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Surgical gastrectomy is considered the standard treatment for patients with UD-type gastric cancer, and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is limited in mucosal-confined UD-type gastric cancer with no evidence of ulceration less than 2 cm in size [11,16].

The early detection of gastric cancer is even more important because it can be cured using endoscopic treatment alone, which is associated with similar long-term survival rates as those of surgery and yields a better post-intervention quality of life than does surgery [16,17,18,19,20]. Therefore, in Korea and Japan, where the prevalence is high, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is performed biennially through population-based gastric cancer screening by the national (Korea) or municipal government (Japan) [21,22].

Because of the relationship between endoscopic screening interval and the stage at diagnosis, cancer-related mortality in many studies suggests an appropriate endoscopy interval for early detection [5,23]. However, to our knowledge, no study has focused on the relationship between clinicopathological features and the impact of previous endoscopic examinations with UD-type gastric cancer. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the impact of the interval between previous endoscopy and diagnosis by analyzing the stage at diagnosis, cancer-related mortality, modality of treatment reassessment, and histology of UD-type gastric cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and ethical concerns

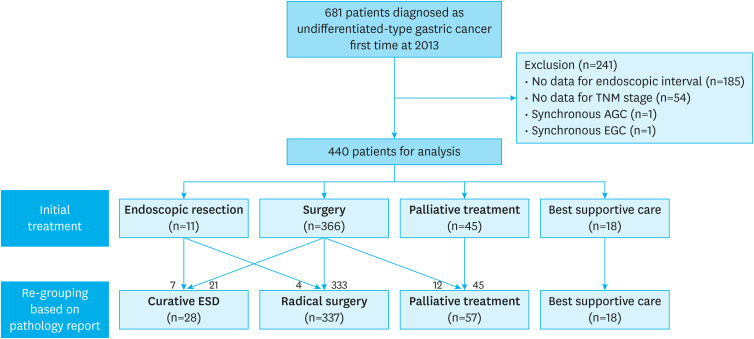

This retrospective study included patients aged >18 years diagnosed with initial-onset UD-type gastric cancer at Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea, between January 1 and December 31, 2013. UD-type gastric cancer included poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell carcinoma in this study. A flow diagram of the study design is presented in Fig. 1. The patients' clinicodemographic data were analyzed, and they were also asked to fill out an electronic questionnaire developed by our hospital during the first visit before referral to the outpatient clinic. The questionnaire consisted of the following questions: (a) Did you undergo EGD before you were diagnosed with gastric cancer? (b) If you underwent an EGD before diagnosis, how much time elapsed between the penultimate endoscopy and the diagnosis? (c) Did you have gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain, discomfort, soreness, and dyspepsia, shortly before the gastric cancer diagnosis through endoscopy? In addition, data on the date of the last outpatient visit were collected to calculate the survival period.

Fig. 1. Study flow.

TNM = tumor, node, metastasis; AGC = advanced gastric cancer; EGC = early gastric cancer.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. H-1804-128-940). All patient data were anonymized and de-identified before analysis; thus, the requirement for patient consent was waived.

Endoscopic interval

The interval between the previous endoscopy and diagnosis was investigated by choosing categorical variables in the groups: group 1: 0–11 months interval; group 2, 12–23 months interval; group 3, 24–35 months interval; group 4, ≥36 months interval; and group 5, no history of endoscopy). This was confirmed by checking the certificate from the referred hospital and the date of the endoscopic image, if possible. Particularly, for patients whose responses indicated less than 12 months, the response was confirmed again to reduce the potential bias resulting from patients possibly confusing previous endoscopy with endoscopy at the time of gastric cancer diagnosis. Mortality data with the cause of death were obtained from electronic medical records and Statistics Korea.

Initial treatment modality and reclassification

Patents were first grouped by initial treatment modalities: endoscopic treatment, surgery, palliative chemotherapy, and best supportive care. The ESD indication for UD-type EGC was macroscopically visible intramucosal cancer (cT1a) less than 2 cm in diameter, without ulceration and lymphovascular invasion. Surgical resection was primarily recommended for patients with resectable cancer who had no indication for ESD. Patients with unresectable gastric cancer received chemotherapy or the best supportive care based on the physician's and patient's decisions. Patients who completed at least one cycle of chemotherapy were classified into the palliative chemotherapy group, while patients with unresectable gastric cancer with a performance status of 3 were classified into the best supportive care group.

For cases of resectable gastric cancer, we investigated the results of ESD or surgery and reclassified them by curability. If non-curative ESD or surgery was achieved, the patients were reclassified into the surgery and palliative chemotherapy groups, respectively (Fig. 1). By contrast, if the final pathologic result of surgery was an indication for ESD, the patients were reclassified into the endoscopic treatment group, even if surgery was the initial treatment.

Staging

Gastric cancer staging was performed according to the 7th edition of the tumor, node, and metastasis staging system proposed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer [24].

The final pathologic staging was used for the statistical analysis. EGC was defined as a tumor confined in the mucosal and submucosal layers, regardless of the lymph node involvement status.

Gross and histopathologic evaluation

Tumor location was assessed endoscopically and categorized according to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association classification criteria [2]. In addition, tumor size, depth of invasion, presence of an ulcer, lymphatic and vascular involvement, and lymph node metastasis were histopathologically evaluated. Histological assessments were performed according to the World Health Organization classification [25]. Poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell carcinoma were classified as UD-type carcinomas.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation, and categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and percentages. The differences in the distributions of the groups according to EGD history were tested using Student's t-tests, Pearson's χ2 test, and linear by linear association test for each variable where appropriate. Differences in patient survival between the groups and the interval between the previous endoscopic exam and diagnosis were determined using the log-rank test and are presented using Kaplan-Meier curves. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 25.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows, and a P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Among the 681 initially screened patients diagnosed with UD-type gastric cancer, 241 patients were excluded for various reasons: 185 patients did not specify the timing of the last endoscopic evaluation, 54 patients did not have sufficient final stage data, and 2 patients had synchronous gastric cancer. Thus, 440 patients were included in the final analysis. The detailed baseline characteristics of all the patients are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 57.1±12.3 years, and 64.1% of the patients were male. In total, 52 patients (11.8%) reported undergoing endoscopy for the first time since being diagnosed with cancer. Most lesions were located in the lower third of the stomach (52.4%). The antrum and lesser curvature were the most frequent sites in the longitudinal and transverse axes. The EGC rate was 58.7%.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Variables | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 57.1±12.3 | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 296 (64.1) | ||

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | |||

| Present | 313 (71.1) | ||

| Interval of previous endoscopic exam (mo) | |||

| <12 | 52 (11.8) | ||

| 12–23 | 114 (25.9) | ||

| 24–35 | 67 (15.2) | ||

| ≥36 | 85 (19.3) | ||

| No history | 122 (27.7) | ||

| Location* | |||

| Upper third | 96 (18.9) | ||

| Mid third | 189 (37.1) | ||

| Lower third | 224 (44.0) | ||

| Esophagogastric junction | 7 (1.4) | ||

| Cardia | 19 (3.7) | ||

| Fundus | 7 (1.4) | ||

| High body | 63 (12.4) | ||

| Mid body | 78 (15.3) | ||

| Low body | 111 (21.8) | ||

| Angle | 69 (13.6) | ||

| Antrum | 151 (29.7) | ||

| Pyloric ring | 4 (0.8) | ||

| Lesser curvature | 151 (29.5) | ||

| Posterior wall | 105 (28.4) | ||

| Greater curvature | 105 (20.5) | ||

| Anterior wall | 110 (21.5) | ||

| Macroscopic type† | |||

| EGC | |||

| Elevated | 6 (1.4) | ||

| Flat | 42 (9.8) | ||

| Depressed | 154 (35.8) | ||

| Mixed | 20 (4.7) | ||

| AGC | |||

| Borrmann type I | 7 (1.6) | ||

| Borrmann type II | 29 (6.7) | ||

| Borrmann type III | 128 (29.8) | ||

| Borrmann type IV | 43 (10.0) | ||

| Histology | |||

| Adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated | 176 (40.0) | ||

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 264 (60.0) | ||

| Depth of invasion | |||

| pT1 | 222 (58.7) | ||

| pT2 | 35 (9.3) | ||

| pT3 | 55 (14.6) | ||

| pT4 | 65 (17.2) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| pN0 | 257 (68.0) | ||

| pN1 | 32 (8.5) | ||

| pN2 | 43 (11.4) | ||

| pN3 | 45 (10.2) | ||

| Distant metastasis | |||

| M0 | 395 (83.0) | ||

| M1 | 75 (17.0) | ||

| Stage | |||

| I | 231 (52.5) | ||

| II | 63 (14.3) | ||

| III | 71 (16.1) | ||

| IV | 75 (17.0) | ||

| Reassessed treatment modality | |||

| Endoscopic resection | 28 (6.4) | ||

| Radical surgery | 337 (76.6) | ||

| Palliative treatment | 57 (13.0) | ||

| Best supportive care | 18 (4.1) | ||

Data are shown as mean±standard deviation or number (%).

EGC = early gastric cancer; AGC = advanced gastric cancer.

*440 patients with 509 longitudinal locations and 511 transverse locations were analyzed; †Ten patients lacked information on gross type, and all were stage IV.

Relationship between EGD interval and stage

Fig. 2 shows the proportion of patients by the stage at diagnosis according to the interval between the previous endoscopic examination and diagnosis. The proportion of stage I patients decreased with every 12-month interval between the previous endoscopic exam and diagnosis (P<0.001).

Fig. 2. Relationship between esophagogastroduodenoscopy interval and stage. The proportion of stage I patients decreased with every 12 months of the interval between previous endoscopic examinations.

*Pearson's χ2 test.

As the interval between the previous endoscopy and the initial diagnosis increased, the proportion of EGC decreased (P<0.001; Fig. 3). By contrast, the proportion of patients with AGC decreased as the interval between previous endoscopy and diagnosis decreased (P<0.001). The point at which the diagnostic rates of EGC and AGC intersect is when the previous endoscopy was performed 3 years before the diagnosis of gastric cancer.

Fig. 3. Proportions of EGCs and AGCs according to the interval of previous endoscopic exam. As the previous interval before the initial diagnosis increased, the proportion of EGC decreased.

EGC = early gastric cancer; AGC = advanced gastric cancer.

*Linear by linear association test.

Relationship between the interval between previous endoscopic exam and diagnosis and gastric cancer-related mortality

The relationship between the interval between previous endoscopic examination and diagnosis and cancer-related mortality in 440 patients with UD-type gastric cancer was statistically significant (Fig. 4). The median follow-up time was 34.4 months (range, 1–47 months). The mean survival time was 39.3±0.7 months (95% confidence interval, 37.936–40.610). When the survival rate was analyzed based on a 24-month interval of previous EGD, survival was significantly different (Fig. 4A, P<0.05). Analysis based on the 36-months interval between previous EGD and diagnosis also showed differences in survival (Fig. 4B, P<0.05).

Fig. 4. Relationship between the interval between previous endoscopic exam and diagnosis and gastric cancer-related mortality. The relationship between the interval between previous endoscopic exam and diagnosis and cancer-related mortality with undifferentiated gastric cancer showed a significant difference.

Relationship between EGD interval and treatment modality

The relationship between the period from the previous endoscopy to the diagnosis and treatment modality is shown in Fig. 5. It shows a decreasing trend of ESD with an increased interval between previous endoscopic exam and diagnosis, with statistical significance (P<0.01).

Fig. 5. Relationship between esophagogastroduodenoscopy interval of previous exam and reassessed treatment modality. There was a significant decreasing trend in the interval between the previous endoscopic examinations and diagnosis and the proportion of endoscopic submucosal dissection (P<0.01).

*Linear by linear association test.

DISCUSSION

Although previous reports of UD-type gastric cancer showed more aggressive characteristics, none have been correlated with endoscopic intervals. As the prevalence is still high in Korea and Japan, the importance of early detection and minimally invasive treatment of gastric cancer is emphasized. An analysis of the detailed pathology of gastric cancer is necessary [3,4,26,27]. A recent nationwide population-based study in Korea showed a significant reduction in the mortality rate (odds ratio [OR], 0.79) from gastric cancer, and the reduction was more significant when using endoscopy (OR, 0.53) [27]. However, this study is based on insurance claim data; therefore, it is difficult to obtain individual information, including the histological type of treatment results [27].

Compared with other studies not analyzed according to the detailed pathology, the rates of EGC (72.3%, 69.7%, 71.0%, and <12 months, 12–23 months, 24–35 months, respectively) and stage I (65.4%, 63.2%, 64.2%, and <12 months, 12–23 months, 24–35 months, respectively) were low even when the EGD was received within 3 years in this study. Thus, the early diagnosis of UD-type gastric cancer tends to be difficult, in line with previous studies.

Our study showed that cancer-related mortality in UD-type gastric cancer decreased when endoscopy was performed within 24 months or 36 months before diagnosis, which is similar to the results of previous studies on the overall histologic type [4,23,28]. These results can provide the basis for the use of endoscopic examination intervals of up to 3 years in reducing cancer-related mortality in UD-type gastric cancer.

Even if EGD was performed within 36 months, there was quite a low rate of curative ESD available (11.5%, 9.6%, 3.0%, and <12 months, 12–23 months, 24–35 months, respectively) when reclassifying treatment groups according to the final outcome. This is thought to have influenced our policy of more aggressive treatment for UD-type gastric cancer in view of the lymph node metastasis rate.

However, there are also strong points in our study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to reveal the impact of the interval between previous endoscopic exam and diagnosis with UD-type gastric cancer. Second, detailed information, including initial treatment modality, histologic type, curability and outcome of initial treatment, and period of endoscopy before diagnosis, were analyzed by reviewing the individual medical records, which is not feasible in large-scale studies using insurance claim data. Third, we reassessed the treatment modality using the final pathologic report according to initial treatment options to overcome the discrepancies before and after the procedure, including ESD and surgery. Finally, this study showed the impact of the interval for screening endoscopy in reducing cancer-related mortality.

The results of this study should be considered in light of some limitations. First, the possibility of selection bias cannot be ruled out because the study participants were recruited from a single center. Moreover, the cohort may represent the general population of gastric cancer patients, as many patients with AGC and UD-type were included in the analysis because of a single population of a tertiary referral hospital. Second, it was difficult to analyze the association of the screening interval with known risk factors for gastric cancer, such as atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Third, information about previous endoscopy in this study was investigated using a self-report questionnaire at the time of the first visit to minimize recall bias; however, these data may still be subjective, as patients with short intervals within one year are more likely to incorrectly report the timing of their last evaluation confused with the last EGD before referral. Finally, because this study was conducted in a high-incidence country, the results may not be applicable in countries with a relatively low incidence of gastric cancer.

In conclusions, the interval between previous endoscopy and diagnosis is associated with the early diagnosis of UD-type gastric cancer, increased possibility of endoscopic cure, and lower mortality. The effective screening interval for reducing mortality and increasing the probability of endoscopic cure was ≤3 years.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Footnotes

- Conceptualization: L.A., C.H., L.H.J.

- Data curation: L.A., C.H., L.H.J.

- Formal analysis: L.A., K.J.L.

- Investigation: A.H.S., C.S.J.

- Methodology: K.S.H., S.Y.S.

- Resources: C.H.N., Y.H.K., K.S.G.

- Software: L.A., C.H., L.H.J.

- Supervision: C.H., L.H.J.

- Validation: L.A., C.H., L.H.J.

- Visualization: L.A., C.H., L.H.J.

- Writing - original draft: L.A.

- Writing - review & editing: L.A., C.H., L.H.J.

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamashima C, Narisawa R, Ogoshi K, Kato T, Fujita K. Optimal interval of endoscopic screening based on stage distributions of detected gastric cancers. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:740. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3710-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin S, Jeon SW, Kwon Y, Nam SY, Yeo SJ, Kwon SH, et al. Optimal endoscopic screening interval for early detection of gastric cancer: a single-center study. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33:e166. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park CH, Kim EH, Chung H, Lee H, Park JC, Shin SK, et al. The optimal endoscopic screening interval for detecting early gastric neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4) Gastric cancer. 2017;20:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0622-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adachi Y, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Sato K, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Pathology and prognosis of gastric carcinoma: well versus poorly differentiated type. Cancer. 2000;89:1418–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun LB, Zhao GJ, Ding DY, Song B, Hou RZ, Li YC. Comparison between better and poorly differentiated locally advanced gastric cancer in preoperative chemotherapy: a retrospective, comparative study at a single tertiary care institute. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:280. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim I, Cheung D, Kim JI, Kim JJ. Risk factors of lymph node metastasis in undifferentiated early gastric cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:171. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Li M, Chen S, Hu J, Guo Q, Liu R, et al. Endoscopic screening in Asian countries is associated with reduced gastric cancer mortality: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:347–354.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura R, Omori T, Mayanagi S, Irino T, Wada N, Kawakubo H, et al. Risk of lymph node metastasis in undifferentiated-type mucosal gastric carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17:32. doi: 10.1186/s12957-019-1571-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HH, Song KY, Park CH, Jeon HM. Undifferentiated-type gastric adenocarcinoma: prognostic impact of three histological types. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:254. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kook MC. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in undifferentiated-type gastric carcinoma. Clin Endosc. 2019;52:15–20. doi: 10.5946/ce.2018.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piessen G, Messager M, Leteurtre E, Jean-Pierre T, Mariette C. Signet ring cell histology is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma regardless of tumoral clinical presentation. Ann Surg. 2009;250:878–887. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b21c7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, et al. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3–15. doi: 10.1111/den.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YG, Kong SH, Oh SY, Lee KG, Suh YS, Yang JY, et al. Effects of screening on gastric cancer management: comparative analysis of the results in 2006 and in 2011. J Gastric Cancer. 2014;14:129–134. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2014.14.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YI, Kim YW, Choi IJ, Kim CG, Lee JY, Cho SJ, et al. Long-term survival after endoscopic resection versus surgery in early gastric cancers. Endoscopy. 2015;47:293–301. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang S, Zhang Z, Liu M, Li S, Jiang C. Endoscopic resection compared with gastrectomy to treat early gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim SG, Ji SM, Lee NR, Park SH, You JH, Choi IJ, et al. Quality of life after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Gut Liver. 2017;11:87–92. doi: 10.5009/gnl15549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goto R, Hamashima C, Mun S, Lee WC. Why screening rates vary between Korea and Japan--differences between two national healthcare systems. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:395–400. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim Y, Jun JK, Choi KS, Lee HY, Park EC. Overview of the National Cancer Screening Programme and the cancer screening status in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:725–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi SI, Park B, Joo J, Kim YI, Lee JY, Kim CG, et al. Three-year interval for endoscopic screening may reduce the mortality in patients with gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:861–869. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077–3079. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1362-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu B, El Hajj N, Sittler S, Lammert N, Barnes R, Meloni-Ehrig A. Gastric cancer: classification, histology and application of molecular pathology. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3:251–261. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jun JK, Choi KS, Lee HY, Suh M, Park B, Song SH, et al. Effectiveness of the Korean national cancer screening program in reducing gastric cancer mortality. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1319–1328.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam JH, Choi IJ, Cho SJ, Kim CG, Jun JK, Choi KS, et al. Association of the interval between endoscopies with gastric cancer stage at diagnosis in a region of high prevalence. Cancer. 2012;118:4953–4960. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]