Abstract

Background: Investigators have tested interventions delivered by specialty palliative care (SPC) clinicians, or by clinicians without palliative care specialization (primary palliative care, PPC).

Objective: To compare the characteristics and outcomes of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of SPC and PPC interventions.

Design: Systematic review secondary analysis.

Setting/Subjects: RCTs of palliative care interventions.

Measurements: Interventions were classified SPC if delivered by palliative care board-certified or subspecialty trained clinicians, or those with extensive clinical experience; all others were PPC. We abstracted data for each intervention: delivery setting, delivery clinicians, outcomes measured, trial results, and Cochrane's Risk of Bias. We conducted narrative synthesis for quality of life, symptom burden, and survival.

Results: Of 43 RCTs, 27 tested SPC and 16 tested PPC interventions. SPC interventions were more comprehensive (4.2 elements of palliative care vs. 3.1 in PPC, p = 0.02). SPC interventions were delivered in inpatient (44%) or outpatient settings (52%) by specialty physicians (44%) and nurses (44%); PPC interventions were delivered in inpatient (38%) and home settings (38%) by nurses (75%). PPC trials were more often of high risk of bias than SPC trials. Improvements were demonstrated on quality of life by SPC and PPC trials and on physical symptoms by SPC trials.

Conclusions: Compared to PPC, SPC interventions were more comprehensive, were more often delivered in clinical settings, and demonstrated stronger evidence for improving physical symptoms. In the face of SPC workforce limitations, PPC interventions should be tested in more trials with low risk of bias, and may effectively meet some palliative care needs.

Keywords: randomized clinical trials, risk of bias, specialty palliative care

Introduction

Palliative care benefits seriously ill patients and their caregivers by providing expert services in pain and symptom management, social and spiritual support, and guidance with advance care planning and goal setting.1 Despite demonstrated effectiveness of palliative care interventions, an international shortage and geographic maldistribution of specialty palliative care (SPC) clinicians means that many patients who could benefit from SPC lack access to it.2–7 One potential solution is to expand “primary palliative care” (PPC), defined as delivery of some elements of palliative care (e.g., basic symptom management, advance care planning, or goal setting) by clinicians who do not specialize in palliative care.8 In the context of the aging population and growing burden of serious illness, SPC and PPC may be required to meet all patients' palliative care needs.9,10

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have tested SPC and PPC interventions; to date, no comparison of the two models exists. Differences between SPC and PPC are important to understand when considering interventions to meet patients' palliative care needs, both in settings with ready access to SPC teams and in settings with limited access to SPC services.11,12 Groups have worked to define characteristics of effective PPC, including capitalizing on expert understanding of and ability to treat underlying illness.13,14 Since SPC programs do not have adequate staffing to meet the needs of all patients with serious illness, it is important to understand when and how PPC interventions work, so as to allocate SPC most efficiently.15

In 2016, Kavalieratos et al. published a systematic review that synthesized the evidence on palliative care interventions tested in RCTs.1 While some of the trials tested SPC interventions and others tested PPC interventions, no trial compared the two types of interventions head-to-head. PPC interventions may differ from those delivered by specialist counterparts, in terms of the elements of palliative care included in the intervention (e.g., symptom management, advance care planning), delivery setting, delivery clinicians, types of outcomes measured (e.g., symptom burden, utilization), and results. We therefore conducted a secondary analysis using all RCTs included in the aforementioned systematic review to highlight differential content and efficacy of SPC and PPC interventions, allowing future interventions to incorporate and test evidence-supported aspects of palliative care in different contexts. The aim of our analysis was to compare SPC versus PPC interventions for elements of palliative care, delivery setting, delivery clinicians, types of outcomes measured, and results.

Methods

Systematic review

We present a secondary analysis of data abstracted from 43 clinical trials reported across 56 articles included in our previous systematic review.1 The parent systematic review searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library's CENTRAL from inception to July 22, 2016. Interventions were included if they comprised at least two elements of palliative care, as defined by the National Consensus Project (NCP) for Quality Palliative Care. The eight NCP elements include structure and processes of care; physical, psychological, social, spiritual, or cultural aspects of care; care of the imminently dying; and ethical and legal aspects of care.16 Interventions had to target adult patients (≥18 years) with life-threatening illness, and to report on at least one of nine patient-level outcomes: patient quality of life (QOL), symptom burden, mood, survival, advance care planning, site of death, resource utilization, health care expenditures, or satisfaction with care.16

Data extraction and risk of bias

Two of four investigators independently used structured forms to extract data from trials' primary and secondary reports, and assessed risk of bias (high, low, unclear) using a modified version of the Cochrane Collaboration's tool.17 For cases in which data fields could not be discerned from the original article, extractors referred to associated articles and supplementary materials. In rare cases, trial authors were contacted to provide additional detail necessary to article assessment.

Characterization of interventions

In the parent systematic review, we characterized each intervention three ways: (1) elements of palliative care, (2) delivery setting, (3) delivery clinicians, (4) types of outcomes measured, and (5) results. As a measure of intervention comprehensiveness, we summed and averaged the number of NCP elements of palliative care addressed in each intervention. Delivery setting was classified as inpatient, outpatient, home hospice, home without hospice, inpatient hospice, nursing home, rehab facility, and/or telehealth/other. Delivery clinicians who were involved in the intervention were classified as SPC or PPC physicians, advance practice providers (APP; nurse practitioners or physician assistants), and registered nurses. The types of patient and caregiver outcome measures were classified into nine major categories: QOL, symptom burden, mood, survival, advance care planning, place of death, health services utilization, health care expenditures, and satisfaction with care. Trial results were described for the most common outcome types: quality of life, symptom burden, and survival.

SPC and PPC interventions

For this analysis, investigators classified each palliative care intervention as SPC or PPC. SPC was defined as interventions primarily involving clinicians who were either palliative care board-certified or subspecialty trained. For U.S.-based trials that took place before Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) accreditation in 2012, SPC clinicians were those who were described as having extensive clinical experience in palliative care (e.g., in-depth communication skills training, ethics consultant, or extensive experience in hospice or palliative care consultation).16,18 Interventions that were led by nonspecialty-palliative care trained clinicians or teams, but had access to SPC clinicians for difficult cases or coaching were considered PPC. All other trials were also considered PPC. Three authors, including one palliative care physician, classified interventions as SPC or PPC (N.C.E., M.B., L.C.H.).

Analysis

We present descriptive statistics for the elements of palliative care, delivery setting, delivery clinicians, and types of outcomes measured. We conducted two-tailed t-tests to assess differences between the number of SPC and PPC elements and types of outcomes measured. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for tests. Due to the small sample size and descriptive nature of the analysis, we do not present tests of statistical significance for each binary comparison (i.e., individual elements of palliative care, delivery settings, delivery clinicians, and individual types of outcomes measure).

Synthesis of results

We synthesized evidence for the effect of SPC and PPC interventions on three commonly reported outcome types, which, due to heterogeneity of outcome measures and small numbers when comparing the two groups (SPC and PPC), was limited to narrative summary. We include quality of life at one to three months, symptom burden at one to three months, and survival in SPC versus PPC interventions.1

Results

Of 43 palliative care RCTs included, 27 were classified as SPC and 16 were classified as PPC.

Risk of bias

Overall, only 7 (16%) of the 43 trials had a low risk of bias; most (n = 25, 58%) had a high risk of bias, and 11 (26%) had unclear risk of bias (Table 1). Of the 27 SPC trials, 5 (19%) had a low risk of bias. Only 2 trials (13%) of the 16 PPC interventions had a low risk of bias.

Table 1.

Risk of Bias

| Risk of bias n (%) | SPC interventions (n = 27) | PPC interventions (n = 16) |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 5 | 2 |

| Trials | Bakitas et al.3 | Lowther et al.53 Northouse et al.54 |

| Higginson et al.19 | ||

| Rummans et al.20 | ||

| Temel et al.2 | ||

| Zimmermann et al.21 | ||

| High | 14 | 11 |

| Trials | Aiken et al.28 | Chapman et al.63 Dyar et al.32 Engelhardt et al.41 Given et al.29 Grande et al.64 Hughes et al.42 McCorkle et al.65 McCorkle et al.30 Northouse et al.31 Radwany et al.33 Steel et al.66 |

| Bakitas et al.22 | ||

| Brännström et al.55 | ||

| Cheung et al.56 | ||

| Clark et al.25 | ||

| Farquhar et al.57 | ||

| Farquhar et al.35 | ||

| Hopp et al.58 | ||

| Pantilat et al.59 | ||

| Rabow et al.60 | ||

| Sidebottom et al.26 | ||

| Wallen et al.61 | ||

| Wong et al.27 | ||

| Zimmer et al.62 | ||

| Unclear | 8 | 3 |

| Trials | Ahronheim et al.67 | Gade et al.37 Northouse et al.34 The SUPPORT Investigators38 |

| Bekelman et al.23 | ||

| Brumley et al.68 | ||

| Edmonds et al.36 | ||

| Grudzen et al.24 | ||

| Hanks et al.69 | ||

| Jordhøy et al.70 | ||

| Kane et al.71 |

PPC, primary palliative care; SPC, specialty palliative care.

Elements of palliative care

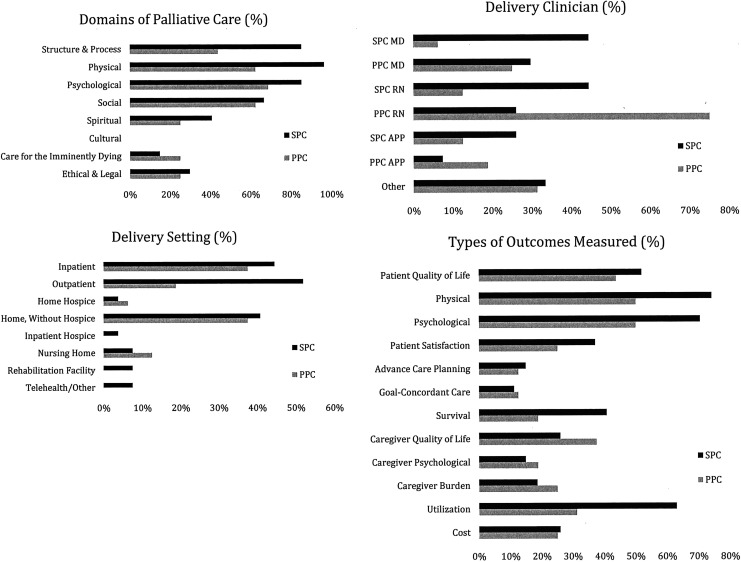

Across all studies, interventions had an average 3.8 out of 8 NCP elements of palliative care. On average, SPC interventions were more comprehensive, incorporating 4.2 elements, whereas PPC intervention incorporated 3.1 elements (p = 0.02). In terms of NCP domains, interventions most frequently addressed structure and processes of care (reorganizing care delivery to include palliative care), physical symptom management, and psychological symptom management. A greater proportion of SPC interventions included structural (SPC: 23/27, 85% vs. PPC: 7/16, 44%) and physical (SPC: 26/27, 96% vs. PPC: 10/16, 63%) aspects of care (Fig. 1). No interventions explicitly incorporated cultural elements of care.

FIG. 1.

Palliative care elements, delivery setting, delivery clinician, and types of outcomes measured in trials of SPC and PPC by percent. PPC, primary palliative care; SPC.

Delivery setting

SPC interventions tended to be delivered in inpatient (12/27; 44%) and/or outpatient settings (14/27, 52%). PPC interventions were often delivered in inpatient (6/16, 38%) and home settings (6/16, 38%). Interventions in outpatient settings were disproportionately more likely to be of SPC compared to PPC (52% vs. 19%, respectively; Fig. 1).

Delivery clinicians

SPC interventions tended to be delivered equally by physicians (12/27, 44%) or nurses (12/27, 44%). PPC interventions were often delivered by nurses (12/16, 75%). Taken in combination with delivery setting, SPC interventions were more likely to be delivered by physicians in clinical (inpatient or outpatient) settings than PPC interventions, which are more likely to be nurse-led in home-based settings.

Types of outcomes measured

Across all studies, trials assessed an average of 4.1 outcomes. On average, SPC interventions assessed 4.5 outcomes and PPC intervention assessed 3.5 outcomes (p = 0.09). In both SPC and PPC trials, most studies assessed physical (respectively, n = 20/27, 74%; 8/16, 50%) and psychological (respectively, n = 19/26, 70%; 8/16, 50%) symptom burden outcomes. Patient quality of life was assessed in 14/27 (54%) of SPC trials and in 7/16 (41%) of PPC trials. Measurement of caregiver outcomes (quality of life, psychological symptoms, and burden) did not differ between SPC and PPC interventions. SPC trials assessed utilization more often than PPC trials (17/27, 63% vs. 5/16, 31%; Fig. 1). Overall, most interventions assessed patient quality of life, physical, and psychological outcomes, and trials of SPC were more likely to measure utilization outcomes than trials of PPC.

Narrative synthesis of results

Twenty-one trials assessed quality of life at one to three months follow-up. Of those, 15 were trials of SPC interventions and 6 of PPC. Five of the 15 SPC trials had low risk of bias3,19–21; of the 5 SPC trials with low risk of bias, one of those studies indicated that SPC improved quality of life.2 Among the 10 SPC trials with high or unclear risk of bias,22–24 4 indicated an improvement in quality of life.25–28 No PPC trials had a low risk of bias. Six PPC trials had a high risk of bias,29–33 one of which indicated an improvement in quality of life at one to three months follow-up.34 Overall, the evidence indicates that both SPC and PPC may improve quality of life, although most trials had high or unclear risk of bias, particularly those of PPC; only one of five trials that had a low risk of bias for either SPC or PPC indicated an association with improved quality of life.

Twenty trials assessed symptom burden at one to three months follow-up. Of those, 16 were trials of SPC interventions and 4 were PPC. Five SPC trials had a low risk of bias,19,21 three of which showed a decrease in symptom burden at one to three months follow-up.2,3,20 Among the 11 SPC trials with either a high or unclear risk of bias,22,35 4 indicated palliative care reduced symptom burden.26–28,36 All four PPC trials were deemed to be at high or unclear risk of bias and did not show a difference in symptom burden (Table 1).29,33,37,38 Overall, several SPC trials had both a low risk of bias and indicated an improvement in symptom burden. PPC trials were generally of a high or unclear risk of bias and did not indicate impacts on symptom burden.

Fifteen trials assessed survival. Of those, 11 were trials of SPC interventions and 4 of PPC. Two of the 11 SPC trials had low risk of bias3; one of those trials with low risk of bias favored the SPC intervention versus control.19 Five SPC trials had a high risk of bias26; one of which indicated SPC improved survival.2 Four trials had an unclear risk of bias. Among the four SPC trials with unclear risk of bias,24,39 one indicated that SPC improved survival.40 Of the four PPC trials that assessed survival, two had unclear and two had high risk of bias; none showed an effect of the PPC intervention on survival.37,38,41,42 Overall, the body of evidence suggests that SPC interventions do not adversely affect survival, while this outcome is rarely assessed for PPC interventions, and the trials often have high or unclear risks of bias.

Discussion

Understanding differences between SPC and PPC interventions in terms of content and efficacy will allow future interventions to incorporate and test evidence-based aspects of palliative care in novel ways. Innovation in palliative care intervention development will be essential to address the needs of patients with serious illness in the face of the SPC workforce shortage.8,43 We found notable differences in elements of palliative care, delivery setting, delivery clinicians, and types of outcomes measured between SPC and PPC interventions. In terms of elements of palliative care, PPC were less likely than SPC interventions to incorporate structural or physical aspects of care. Of note, no PPC or SPC interventions addressed cultural aspects of care, an important element of palliative care for aligning culturally based preferences with treatments, especially in light of disparities in palliative care.44,45 SPC and PPC trials differed in terms of delivery settings (respectively, often clinical settings, delivered by physicians vs. home-based settings with nurses). For example, based on existing access to and skills of delivering clinicians, PPC interventions may suit for support for the imminently dying (which was also more frequently addressed by PPC than SPC interventions) for whom travel outside of the home may be challenging.

Both SPC and PPC interventions were associated with improvements in outcomes, particularly quality of life, among patients with serious illness. The evidence indicates that neither form of palliative care is associated with shorter survival compared to control. SPC was associated more strongly with decreased symptom burden than PPC. Conducting additional PPC trials with low risk of bias that target and measure symptom burden as an outcome may be reasonable given the relatively high risk of bias among the PPC trials included in this review that captured symptom burden.

There are important gaps in palliative care research across trials, in both SPC and PPC. First, one area for strengthening palliative care trials is explicitly basing them in behavioral intervention and theories of palliative care delivery. Second, studies should be designed to identify the active ingredients of effective palliative care and their causal pathways in impacting outcomes. Although some studies have started to investigate the role of SPC, palliative care research as a field has not yet fully examined the mechanisms of SPC, which introduces difficulties in adapting existing models of SPC to PPC.46–49 For example, additional research can shed light on how palliative care works to improve outcomes mechanistically and the core functions of palliative care. Then, additional trials can test those interventions designed to meet those core functions in different ways (e.g., PPC). For example, Hoerger et al. evaluated elements of palliative care that were associated with outcomes in an RCT using the NCP elements of palliative care.46 Future RCTs can and should collect more nuanced data about those elements, including the elements of palliative care covered in consults, appointments, and visits. This approach would be very informative with respect to identifying elements of palliative care that can then be applied and tested across other settings. Third, after identifying core elements and functions of palliative care, interventions can adapt delivery setting and delivery clinicians, which can then be evaluated to determine the impacts of adaptation on effectiveness. Nurses are able to (and do) extend into the community in ways that physicians and APPs often cannot due to workforce constraints, payment structure, time of patient visits, and intensity of needs. Furthermore, researchers and clinicians can work to discover ways PPC and SPC can be integrated to work seamlessly together as one comprehensive model of care given the workforce and constraints of both.

Considering implementation, differences across SPC and PPC interventions in terms of delivery mechanisms may be reasonably attributed to differential provider availability, workloads, skillsets, and comfort levels. In PPC settings, nurses may be more feasible, particularly in home-based and telephonic interventions.22 In our data, fewer than half (44%) of SPC interventions were delivered by nurses and that number increased to three-quarters for PPC interventions. This concept is interesting epidemiologically in the context of growing home-based patient populations and care models.42,50,51 PPC has potential to have a large impact on patient-centered outcomes at the population level given its scalability relative to SPC. Of note, interventions may be differently titrated for settings with some access to SPC (e.g., coaching, collaborative models of SPC, and PPC) versus no access (e.g., home-based serious-illness care models in rural areas).

Limitations

Extensive heterogeneity of interventions in terms of the elements of palliative care, delivery (setting and provider type), outcome assessment, and reporting of results made it difficult to compare across studies. Future interventions should clearly outline their theory-based proposed mechanisms of palliative care and use standardized, validated outcome measures with clear description of statistical methods.

Although SPC interventions were, on average, one domain more comprehensive than PPC interventions, we could not assess more nuanced indicators of intervention breadth and depth, such as the differential intensity with which the elements were delivered between the SPC and PPC interventions. Even within a domain of palliative care, specific intervention approaches to delivery can be quite diverse and have different levels of intensity, which we could not fully assess in this review. Therefore, we cannot yet determine if SPC and PPC are equally effective in improving patient-centered outcomes. Future head-to-head trials should compare relative effectiveness of SPC and PPC for meeting the needs of different populations. Real-world implementation and dissemination of SPC interventions will still be dependent on access to SPC clinicians. While many clinicians may be providing PPC, evidence suggests that current delivery in non-SPC settings can be greatly enhanced.13,52 There are also likely existing interventions that could be considered PPC, but do not use the same palliative care language search used in the systematic review. This may be particularly Germaine when considering interventions that include, for example, disease-specific approaches to symptom management.13

Our results are also based on a relatively small sample size (N = 43 trials), which when combined with the heterogeneity of interventions and trial design, yielded small cell size when examining specific domain, settings, types of outcome measures, and results. Our narrative synthesis of results only included a subset of results at limited timepoints. A limitation of our analysis was not being able to directly compare the magnitude of improvement between trials of SPC and PPC. Future comparative effectiveness and pragmatic studies can include head-to-head comparisons of SPC and PPC interventions, allowing for the investigation of potential heterogeneity of treatment effects within specific subgroups. Trials of both SPC and PPC continue to be published, of which recent ones are not included in this study.

Conclusions

Compared to PPC, SPC interventions were more comprehensive, were more likely to be delivered in clinical settings by specialty physicians, and were more likely to address physical and structural elements. Both SPC and PPC demonstrated improvements in quality of life; SPC trials also had stronger evidence for beneficial effects on physical symptoms. Testing models of palliative care is difficult in terms of both describing and measuring intervention components and designing behavioral trials to minimize risk of bias. SPC and PPC interventions with different elements of palliative care and delivery may be effective to meet different palliative care needs of seriously ill patients and their families. In addition, high-quality research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms of both SPC and PPC for improving outcomes. As models of palliative care develop, SPC and PPC may complement one another to close gaps in care for the population of patients with serious illness. Well-designed interventions that capitalize on existing skillsets and workforce, and tested in trials with low risk of bias, may help to fill gaps in care for addressing the needs of patients with serious illness in both settings, which do and do not have any access to SPC services.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Sally C. Morton, PhD, Lucas Heller, MD, Janel Hanmer, MD, PhD, Di Zhang, BS, Dara Z. Ikejiani, BS, and Zachariah P. Hoydich, BS, for their support on the initial systematic review and meta-analysis that provided the basis for this study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. : Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;316:2104–2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : Effects of a Palliative Care Intervention on Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Advanced Cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lupu D: Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:899–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murray SA, Boyd K, Sheikh A, et al. : Developing primary palliative care. BMJ 2004;329:1056–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamal AH, Maguire JM, Meier DE: Evolving the palliative care workforce to provide responsive, serious illness care. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morrison R, Meier D: America's Care of Serious Illness. New York, New York, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quill TE, Abernethy AP: Generalist plus specialist palliative care—Creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E: Identifying the population with serious illness: The “denominator” challenge. J Palliat Med 2018;21(S2):S7–S16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind SM, et al. : The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: Projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Heal 2019;7:e883–e892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kamal AH, Bull JH, Wolf SP, et al. : Prevalence and Predictors of Burnout Among Hospice and Palliative Care Clinicians in the U.S. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:690–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12. Groot MM, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Verhagen SCA, et al. : Obstacles to the delivery of primary palliative care as perceived by GPs. Palliat Med 2007;21:697–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gelfman LP, Kavalieratos D, Teuteberg WG, et al. : Primary palliative care for heart failure: What is it? How do we implement it? HHS Public Access. Heart Fail Rev 2017;22:611–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. : Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spetz J, Dudley N, Trupin L, et al. : Few hospital palliative care programs meet national staffing recommendations. Health Aff 2016;35:1690–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. : The National Agenda for Quality Palliative Care: The National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manag 2007;33:737–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. JPT Higgins, S Green: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. 2011. (Last accessed October8, 2018)

- 18. Bannon M, Ernecoff NC, Nicholas Dionne-Odom J, et al. : Comparison of palliative care interventions for cancer versus heart failure patients: A secondary analysis of a systematic review. J Palliat Med 2019;22:966–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higginson IJ, Bausewein C, Reilly CC, et al. : An integrated palliative and respiratory care service for patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:979–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rummans TA, Clark MM, Sloan JA, et al. : Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:635–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721–1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. : Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bekelman DB, Plomondon ME, Carey EP, et al. : Primary results of the patient-centered disease management (PCDM) for heart failure study. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. : Emergency department-initiated palliative care in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clark MM, Rummans TA, Atherton PJ, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of maintaining quality of life during radiotherapy for advanced cancer. Cancer 2013;119:880–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sidebottom AC, Jorgenson A, Richards H, et al. : Inpatient palliative care for patients with acute heart failure: Outcomes from a randomized trial. J Palliat Med 2015;18:134–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wong FKY, Ng AYM, Lee PH, et al. : Effects of a transitional palliative care model on patients with end-stage heart failure: A randomised controlled trial. Heart 2016;102:1100–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aiken LS, Butner J, Lockhart CA, et al. : Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: Program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. J Palliat Med 2006;9:111–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Given B, Given CW, McCorkle R, et al. : Pain and fatigue management: results of a nursing randomized clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum 2002;29:949–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McCorkle R, Jeon S, Ercolano E, et al. : An advanced practice nurse coordinated multidisciplinary intervention for patients with late-stage cancer: A cluster randomized trial. J Palliat Med 2015;18:962–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Northouse L, Kershaw T, Mood D, Schafenacker A: Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychooncology 2005;14:478–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dyar S, Lesperance M, Shannon R, et al. : A nurse practitioner directed intervention improves the quality of life of patients with metastatic cancer: Results of a randomized pilot study. J Palliat Med 2012;15:890–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Radwany SM, Hazelett SE, Allen KR, et al. : Results of the promoting effective advance care planning for elders (PEACE) randomized pilot study. Popul Health Manag 2014;17:106–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al. : Randomized clinical trial of a brief and extensive dyadic intervention for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psychooncology 2013;22:555–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Farquhar MC, Prevost AT, McCrone P, et al. : The clinical and cost effectiveness of a Breathlessness Intervention Service for patients with advanced non-malignant disease and their informal carers: Mixed findings of a mixed method randomised controlled trial. Trials 2016;17:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Edmonds P, Hart S, Wei Gao, et al. : Palliative care for people severely affected by multiple sclerosis: Evaluation of a novel palliative care service. Mult Scler 2010;16:627–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. : Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: A randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med 2008;11:180–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Investigators P: A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. J Am Med Assoc 1995;274:1591–1598 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jordhøy MS, Fayers P, Saltnes T, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Jannert M, Kaasa S. A palliative-care intervention and death at home: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet (London, England) 2000;356:888–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bekelman DB, Allen LA, McBryde CF, et al. : Effect of a collaborative care intervention vs usual care on health status of patients with chronic heart failure. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Engelhardt JB, McClive-Reed KP, Toseland RW, et al. : Effects of a program for coordinated care of advanced illness on patients, surrogates, and healthcare costs: A randomized trial. Am J Manag Care 2006;12:93–100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hughes SL, Cummings J, Weaver F, et al. : A randomized trial of the cost effectiveness of VA hospital-based home care for the terminally ill. Health Serv Res 1992;26:801–817 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kamal AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, et al. : Future of the palliative care workforce: Preview to an impending crisis. Am J Med 2017;130:113–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Johnson KS: Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1329–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Samuel CA, Landrum MB, McNeil BJ, et al. : Racial disparities in cancer care in the Veterans Affairs health care system and the role of site of care. Am J Public Health 2014;104 Suppl 4(S4):S562–S571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hoerger M, Greer JA, Jackson VA, et al. : Defining the elements of early palliative care that are associated with patient-reported outcomes and the delivery of end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:1096–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hannon B, Swami N, Pope A, et al. : Early palliative care and its role in oncology: A qualitative study. Oncologist 2016;21:1387–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Back AL, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. : Clinician roles in early integrated palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med 2014;17:1244–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kavalieratos D: Reading past the p <0.05's: The secondary messages of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in palliative care. Palliat Med 2019;33:121–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Di Pollina L, Guessous I, Petoud V, et al. : Integrated care at home reduces unnecessary hospitalizations of community-dwelling frail older adults: A prospective controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Daaleman TP, Ernecoff NC, Kistler CE, et al. : The impact of a community-based serious illness care program on healthcare utilization and patient care experience. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:825–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kamal AH: Letters “‘who does what?’” ensuring high-quality and coordinated palliative care with our oncology colleagues. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52:e1–e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lowther K, Selman L, Simms V, et al. : Nurse-led palliative care for HIV-positive patients taking antiretroviral therapy in Kenya: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV 2015;2:e328–e334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al. : Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer 2007;110:2809–2818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brännström M, Boman K: Effects of person-centred and integrated chronic heart failure and palliative home care. PREFER: A randomized controlled study. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:1142–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cheung W, Aggarwal G, Fugaccia E, et al. : Palliative care teams in the intensive care unit: A randomised, controlled, feasibility study. Crit Care Resusc 2010;12:28–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Farquhar MC, Prevost AT, McCrone P, et al. : Is a specialist breathlessness service more effective and cost-effective for patients with advanced cancer and their carers than standard care? Findings of a mixed-method randomised controlled trial. BMC Med 2014;12:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hopp FP, Zalenski RJ, Waselewsky D, et al. : Results of a hospital-based palliative care intervention for patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure. J Card Fail 2016;22:1033–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pantilat SZ, O'Riordan DL, Dibble SL, Landefeld CS: Hospital-based palliative medicine consultation: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, McPhee SJ. The comprehensive care team. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wallen GR, Baker K, Stolar M, et al. : Palliative care outcomes in surgical oncology patients with advanced malignancies: A mixed methods approach. Qual Life Res 2012;21:405–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zimmer JG, Groth-Juncker A, McCusker J: Effects of a physician-led home care team on terminal care. J Am Geriatr Soc 1984;32:288–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chapman DG, Toseland RW: Effectiveness of advanced illness care teams for nursing home residents with dementia. Soc Work 2007;52:321–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Grande GE, Todd CJ, Barclay SI, Farquhar MC: Does hospital at home for palliative care facilitate death at home? Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1999;319:1472–1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McCorkle R, Benoliel JQ, Donaldson G, et al. : A randomized clinical trial of home nursing care for lung cancer patients. Cancer 1989;64:1375–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Steel JL, Geller DA, Kim KH, et al. : Web-based collaborative care intervention to manage cancer-related symptoms in the palliative care setting. Cancer 2016;122:1270–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ahronheim JC, Morrison RS, Morris J, et al. : Palliative care in advanced dementia: A randomized controlled trial and descriptive analysis. J Palliat Med 2000;3:265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. : Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hanks GW, Robbins M, Sharp D, et al. : The imPaCT study: A randomised controlled trial to evaluate a hospital palliative care team. Br J Cancer 2002;87:733–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Jordhøy MS, Fayers P, Loge JH, et al. : Quality of life in palliative cancer care: results from a cluster randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:3884–3894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kane RL, Wales J, Bernstein L, et al. : A randomised controlled trial of hospice care. Lancet (London, England) 1984;1:890–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]