Abstract

Palliative care is a values-driven approach for providing holistic care for individuals and their families enduring serious life-limiting illness. Despite its proven benefits, access and acceptance is not uniform across society. The genesis of palliative care was developed through a traditional Western lens, which dictated models of interaction and communication. As the importance of palliative care is increasingly recognized, barriers to accessing services and perceptions of relevance and appropriateness are being given greater consideration. The COVID-19 pandemic and recent social justice movements in the United States, and around the world, have led to an important moment in time for the palliative care community to step back and consider opportunities for expansion and growth. This article reviews traditional models of palliative care delivery and outlines a modified conceptual framework to support researchers, clinicians, and staff in evaluating priorities for ensuring individualized patient needs are addressed from a position of equity, to create an actionable path forward.

Keywords: conceptual framework, COVID-19, health care disparities, palliative care, race factors

Introduction

Palliative care was created to be holistic and personalized to meet patient needs, which countered the status quo at the time. Importantly, palliative care is both a philosophy of care and a set of knowledge, skills, and competencies designed to respond to physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs through engagement of a multidisciplinary team.1 This clinical specialty was created through the sociocultural lens of the United Kingdom and embedded in oncology. Implementation of programs has since increased globally, leading to greater diversity and cultural pluralism. Consequently, needs of the white Anglo majority have influenced care models. Although there is an increasing emphasis on the overall accessibility of palliative care for all patients, models are less well defined.2

As recent global events unfold after the COVID-19 pandemic and concurrent social justice movements, where systemic racial inequities have been especially highlighted, it is imperative the palliative care community steps back to reflect on where and how we can improve access, decrease structural inequalities, and reduce inequities in palliative care.3 To do so, we must begin by naming forms of oppression that compound the effects of racism at all levels.4 As such, there must be a lens through which to view and understand barriers to enable improvement in outcomes.

Access is a multifaceted issue, influenced by characteristics such as appropriateness, affordability, availability, and health care policies impacting all levels.5 The integration of health and science in many countries continues to delineate effective approaches of palliative care and the types of services offered vary by program. Although there is a global consensus that palliative care can be cost-effective,2 health care funding models explain international differences in programs. Countries faring best in palliative care are those that support universal health coverage, facilitating transitions across care with greater ease.6 Palliative care models support individualized care that addresses the myriad of concerns within a patient's life, but application is often hindered by sociocultural and access issues. Therefore, this report aims to present a modified socioecological conceptual framework to help achieve equity in palliative care access and all delivery of services individualized to patient-specific needs.

Traditional Palliative Care Approach

The bio-psychosocial-spiritual model was introduced in 1960 as a clinical and systems approach to integrating the biological, psychological, and social dimensions of illness.7 This approach was instrumental in improving perceptions of quality care,2 potentially because the model directs providers' attention to understanding determinants of health, that is, genetic factors, behavioral factors (e.g., stress and health beliefs), and social conditions (e.g., cultural influences). This patient-centered model of care encourages development of treatment plans, which acknowledge how disease and suffering affect peoples' lives.

Moreover, the bio-psychosocial-spiritual model is intertwined with ecological paradigms, which can further reveal complexities of interactions between health, illness, determinants, and outcomes.8 For instance, there are patient-level obstacles such as culture, beliefs, and mistrust (micro); community-level issues including health literacy and language barriers (meso); and system-level challenges of organizational attitudes toward palliative care and non-concordant care (macro). The combination of these facets of care form a socioecological approach to access of palliative care, negating potential barriers.9 For example, those who are not familiar with palliative care, who have a history of social mistreatment, may be hesitant to engage in programs.5 System-level factors are undoubtedly necessary for adequate access to services; however, patient-level obstacles—the humanistic side of health care—must be acknowledged and addressed.

Contextual Practice Challenges

The importance of palliative care has been well established, yet evidence shows social, cultural, and economic factors limit access.5 Disparities among socially disadvantaged populations (e.g., black low-income groups) have been widely observed in comparison with white counterparts, rendering these groups at higher risk of potentially not receiving goal-concordant care10; although it should be noted discrepancies have also been observed among primarily white rural communities.11 Failure to understand the efficacy of treatment and absence of goals of care conversations can result in more aggressive intervention at the end of life, increased in-hospital deaths, and greater financial burden for families.12

To address these inequities, barriers and facilitators of palliative care access should be considered on multiple levels. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs are often cited as cause for differences in uptake. Although these factors do influence preferences, underlying structural factors must also be considered.13 Marginalized populations, such as black individuals and other people of color, have often pointed to negative encounters with the health care system due to systemic racism and discrimination as rationale for not engaging in palliative care.13 At the provider level, practice styles, poor communication, and lack of cultural humility also pose significant challenges for patients and families.13

Inequitable access to palliative care is even more stark internationally. Approximately 80% of people requiring palliative care annually reside in low- and middle-income countries, but only 14% have access.14 This gap is augmented by a lack of knowledge and acceptance of the palliative care model for care delivery, an unequal distribution of opioids for managing symptoms, and an absolute workforce shortage able to adequately run programs.14

A Modified Palliative Care Conceptual Framework

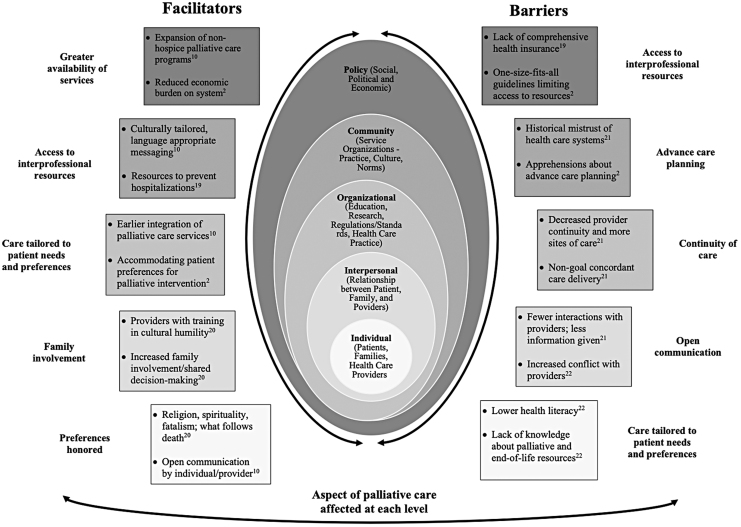

Given challenges in current clinical practice, the bio-psychosocial-spiritual model does not necessarily offer a comprehensive approach to meet the needs of all patients within an ecological framework. The crux of palliative care is providing “holistic” care for patients, but holism may be a misnomer given the breadth of inequities that exist. To demonstrate, we have dovetailed a population example with the socioecological model based on current research and the authors' expertise (Fig. 1). As it stands, this figure provides a visual representation of how the bio-psychosocial-spiritual model is challenged by systems it works within.

FIG. 1.

Barriers and facilitators to palliative care using population example of black patients in the ICU. Boxes represent examples of potential barriers and facilitators black patients in the ICU may face on corresponding socioecological levels (concentric circles). Double-facing arrows on either side are to indicate that these examples may occur on multiple levels. Text on either side of the boxes highlight aspects of palliative care that may be impacted by the indicated barriers and facilitators. ICU, intensive care unit.

Underpinning this example are the multifaceted layers to unique challenges black patients and families may face in the intensive care unit in the United States. However, aspects of palliative care affected at each socioecological level often vary by individual patient based on their value system, religion, and so on. Although, it is critical that we mitigate the perpetuation of any harmful stereotypes, there are often collective worldviews and preferences that exist among some populations.

As one example, studies have shown that some black patients prefer more aggressive interventions at the end of life, for example, intensive care unit admissions; however, this is often viewed as having lack of knowledge about palliative care, rather than as phrased—a preference.13 Documented abuses of human rights increase a sense of distrust “at all levels of care” for some groups.15 Another example is sometimes seen in symptom management preferences across cultural groups. Traditional worldviews lend some Hindus to interpret suffering as result of karma and a way to resolve poor actions from a previous or current life. This may involve enduring pain despite availability of pharmacological interventions.16

Culture provides a contextual backdrop to interpret health-seeking behaviors, yet individual differences prevail.17 Therefore, these two examples are not to be generalized but serve to demonstrate the key takeaway from this call to action in that these worldviews have come to exist from traditional understanding regarding application of the components of palliative care. The traditional Western perspective tends to input assumptions when patients' preferences are not a textbook match, rendering increased potential for implicit bias in the delivery of care. Palliative care is unique as it should open access to a host of interprofessional resources.18 However, at a systemic level, the current trend of providing a one-size-fits-all approach to palliative care may limit patients' access to important resources that are better aligned with their personal beliefs and preferences.18

This framework presents barriers but also opportunities, highlighting how different obstacles could occur depending on an individual's given circumstances. Consider the assumption that a patient with formal education and high health literacy would be better equipped to navigate the health system with minimal challenges, whereas a patient with lower health literacy would be perceived as disadvantaged before stepping foot in the hospital. The capacity for a provider to give consistent care to these two patients is inherently threatened by structural factors modeled in this framework. However, there is also evidence suggesting this may not be the case in reality. Given the complexities of the U.S. health system, a patient's level of education may not be considered, as providers may offer less information to those with greater education, assuming they do not need that additional support.12

Moving Forward

As palliative care providers, we must consider our blind spots. As shown in our population example, and in consideration of other populations disproportionately impacted by health disparities, we cannot call the care we provide holistic while ignoring the systemic racism, discrimination, and traumas many individuals endure throughout encounters with the health care system.4,15 Racial biases have been inherently learned and built into the system palliative care operates within; meaning biases could be experienced at any level on the socioecological spectrum.

When developing effective palliative care programs for diverse populations, locally and globally, it is imperative differences are addressed; each has ramifications for providers, patients, and families. The purpose of this discussion is to provide a visual representation showing the breadth of challenges a given population could encounter. By seeing the interconnectedness of such challenges, we can begin to target how different components of palliative care may be impacted and how we can move the field forward.

Conclusion

Palliative care can improve quality of life, but access to this relief of suffering is not reflected equally across populations. Our conceptual model offers a framework to aid the evolution of palliative care, and to ensure that past and present individualized barriers and challenges are both acknowledged and addressed in future care models. We hope this provides an opportunity for discussion, debate, and moving the field forward.

Authors' Contributions

K.E.N., R.W., and P.M.D. conceptualized the article. K.E.N. and D.H.S. drafted the initial report. B.K. and K.E.N. drafted and refined the initial conceptual framework. P.M.D., M.F., B.K., B.R., D.H.S., D.S.W., and R.W. reviewed the report and conceptual framework in detail, suggesting revisions and areas for further improvement.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO): WHO definition of palliative care. https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. 2019. (Last accessed July8, 2020)

- 2. Payne R: Racially associated disparities in hospice and palliative care access: Acknowledging the facts while addressing the opportunities to improve. J Palliat Med 2016;19:131–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosa WE, Gray TF, Chow K, et al. : Recommendations to leverage the palliative nursing role during COVID-19 and future public health crises. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2020;1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR: On racism: A new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs 2020. DOI: 10.1377/hblog20200630.939347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davidson PM, Phillips JL, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, et al. : Providing palliative care for cardiovascular disease from a perspective of sociocultural diversity: A global view. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2016;10:11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The Economist Intelligence Unit: The 2015 quality of death index: Ranking palliative care across the world. Lien Foundation. https://eiuperspectives.economist.com/healthcare/2015-quality-death-index. 2015. (Last accessed September2, 2020)

- 7. Waccholtz AB, Fitch CE, Makowski S, Tjia J: A comprehensive approach to the patient at end of life: Assessment of multidimensional suffering. South Med J 2016;109:200–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bronfenbrenner U: Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Dev Psychol 1986;22:723–742 [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine: Improving Access to and Equity of Care for People with Serious Illness: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnson K: Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1329–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoerger M, Perry LM, Korotkin BD, et al. : Statewide differences in personality associated with geographic disparities in access to palliative care: Findings on openness. J Palliat Med 2019;22:628–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown CE, Engelberg RA, Sharma R, et al. : Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and healthcare intensity at the end of life. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1308–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Calanzani N, Koffman J, Higginson IJ: Palliative and end of life care for Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic groups in the UK. London: Cicely Saunders Institute, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poudel A, Bhuvan KC, Shrestha S, Nissen L: Access to palliative care: Discrepancy among low-income and high-income countries. J Glob Health 2019;9:1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evans MK, Rosenbaum L, Malina D, et al. : Diagnosing and treating systemic racism. N Engl J Med 2020;383(3):274–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dedeli O, Kaptan G: Spirituality and religion in pain and pain management. Health Psychol Res 2013;1:e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davidson PM, Macdonald P, Moser DK, et al. : Cultural diversity in heart failure management: Findings from the discover study (part 2). Contemp Nurse 2007;25:50–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kelley AS, Meier DE (eds): Meeting the needs of older adults with serious illness: Challenges and opportunities in the age of health care reform. New York: Springer, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Worster B, Bell DK, Roy V, et al. : Race as a predictor of palliative care referral time, hospice utilization, and hospital length of stay: A retrospective noncomparative analysis. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2018;35:110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mayeda DP, Ward KT: Methods for overcoming barriers in palliative care for ethnic/racial minorities: A systematic review. Palliat Support Care 2019;17:697–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mack JW, Paulk E, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG: Black-white disparities in the effects of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1533–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee JJ, Long AC, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA: The influence of race/ethnicity and education on family ratings of the quality of dying in the ICU. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]