Abstract

Exposure to certain anthropogenic chemicals can inhibit the activity to cytochrome P450 aromatase (CYP19) in fishes leading to decreased plasma 17β-estradiol (E2), plasma vitellogenin (VTG), and egg production. Reproductive dysfunction resulting from exposure to aromatase inhibitors has been extensively investigated in several laboratory model species of fish. These model species have ovaries that undergo asynchronous oocyte development, but many fishes have ovaries with group-synchronous oocyte development. Fishes with group-synchronous oocyte development have dynamic reproductive cycles which typically occur annually and are often triggered by complex environmental cues. This has resulted in a lack of test data and uncertainty regarding sensitivities to and adverse effects of aromatase inhibition. The present study used the western mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) as a laboratory model to investigate adverse effects of chemical aromatase inhibition on group-synchronous oocyte development. Adult female western mosquitofish were exposed to either 0, 2, or 30 μg/L of the model nonsteroidal aromatase inhibiting chemical, fadrozole, for a complete reproductive cycle. Fish were sampled at four time-points representing pre-vitellogenic resting, early vitellogenesis, late vitellogenesis/early ovarian recrudescence, and late ovarian recrudescence. Temporal changes in numerous reproductive parameters were measured, including gonadosomatic index (GSI), plasma sex steroids, and expression of selected genes in the brain, liver, and gonad that are important for reproduction. In contrast to fish from the control treatment, fish exposed to 2 and 30 μg/L of fadrozole had persistent elevated expression of cyp19 in the ovary, depressed expression of vtg in the liver, and a low GSI. These responses suggest that completion of a group-synchronous reproductive cycle was unsuccessful during the assay in fish from either fadrozole treatment. These adverse effects data show that exposure to aromatase inhibitors has the potential to cause reproductive dysfunction in a wide range of fishes with both asynchronous and group-synchronous reproductive strategies.

Keywords: Adverse Outcome Pathway, Endocrine Disruption, Fadrozole, Species Extrapolation

1. INTRODUCTION

Cytochrome P450 aromatase (CYP19) is a steroidogenic enzyme involved in the conversion of C19 androgens (e.g. testosterone; T) to C18 estrogens (e.g. 17β-estradiol; E2), making aromatase a key regulator of reproductive processes controlled by E2 (Callard et al., 1978; Simpson, 1994). However, certain anthropogenic chemicals can inhibit the activity of aromatase (Hinfray et al., 2006; Sanderson, 2006; Vinggaard et al., 2000). These chemicals can enter the aquatic environment and potentially cause reproductive dysfunction in fishes (Ankley et al., 2002; Kahle et al., 2008). Inhibition of aromatase activity can reduce concentrations of plasma E2 leading to decreased activation of the estrogen receptor which mediates hepatic synthesis of vitellogenin (VTG), an egg yolk precursor protein required for oocyte development and maturation (Ankley et al., 2002; Callard et al., 1978; Simpson, 1994). Decreased synthesis of VTG results in production of fewer viable eggs leading to population-level declines in fishes (Ankley et al., 2008, Miller et al., 2007). Reproductive dysfunction resulting from exposure to chemicals that inhibit aromatase activity has been extensively investigated in several laboratory model species using standardized reproductive toxicity testing protocols (Ankley et al., 2002; 2005; 2007; 2020; Ayobahan et al., 2019; Celander et al., 2011; Conolly et al., 2017; Doering et al., 2019; Skolness et al., 2013). This extensive investigation has resulted in a relatively well-defined adverse outcome pathway (AOP) with the potential for enabling predictive, AOP-driven ecological risk assessments for native species of regulatory concern (Conolly et al., 2017; Doering et al., 2019; Villeneuve, 2016). However, all of the laboratory model fishes that have been investigated, namely the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas), Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes), and zebrafish (Danio rerio), share similar reproductive strategies and associated reproductive physiologies (Ankley & Johnson, 2004). Specifically, these species have ovaries that undergo asynchronous oocyte development, meaning that the mature ovary contains oocytes at all stages of maturation and recruitment of oocytes occurs continuously, enabling frequent spawning events over an extended spawning season (Wallace & Selman, 1981). During spawning, fishes with asynchronous oocyte development have relatively constant levels of ovarian aromatase activity, plasma E2, plasma VTG, gonadosomatic index (GSI), and egg production which can last a month or more (Ankley et al., 2002; Jensen et al., 2001). Fishes are by far the largest and most diverse group of vertebrates and exhibit vast diversity in their reproductive strategies and associated reproductive physiology (Tyler & Sumpter, 1996; Wallace & Selman, 1981). This diversity among fishes raises questions as to whether the AOP for inhibition of aromatase activity leading to reproductive dysfunction which was developed from studies of fishes with asynchronous oocyte development is applicable to species of fish with other reproductive strategies.

In contrast with fathead minnow, Japanese medaka, and zebrafish, most species of fish have ovaries that undergo group-synchronous oocyte development (Wallace & Selman 1981), including many catfishes (Siluriformes), perches (Perciformes), sturgeon (Acipenseriformes), cods (Gadiformes), halibut (Pleuronectiformes), and trout (Salmoniformes) (Barrett & Munkittrick, 2010; Berg et al., 2004; Burke et al., 1984; Conte et al., 1988; Henderson et al., 2000; Murua & Saborido-Rey, 2003). Fishes with group-synchronous oocyte development have ovaries that contain two distinct populations of oocytes at one time, a synchronous population of larger oocytes, known as the clutch, and a heterogenous population of smaller oocytes from which the next clutch is recruited (Wallace & Selman, 1981). These fishes typically ovulate the entire clutch of mature oocytes in a single, annual spawning event which can last anywhere from a day to a few weeks (Holden & Raitt, 1974). Nonetheless, some species can ovulate two or more clutches each year (Barrett & Munkittrick, 2010). Fishes with group-synchronous oocyte development have dynamic cycles of reproductive parameters which occur over 12 months in many species. Briefly, a female cycle includes four generalized key stages: 1) resting, 2) vitellogenesis, 3) ovarian recrudescence, and 4) spawning. During the resting stage, which typically occurs just after spawning and can last several months, ovarian aromatase activity, plasma E2, plasma VTG, and GSI are at their minimum (Barrett & Munkittrick, 2010; Berg et al., 2004; Bon et al., 1997; Burke et al., 1984; Kumar et al., 2000; Malison et al., 1994; Olsson et al., 1987; Trant et al., 1997). At the onset of vitellogenesis, which is typically triggered by environmental cues (e.g. water temperature, day-length), ovarian aromatase activity is markedly increased causing greater conversion of T to E2 leading to an increase in the concentration of E2 in the plasma (Kumar et al., 2000, Trant et al., 1997). Increased plasma E2 stimulates hepatic synthesis of VTG resulting in an increased level of the protein in the plasma (Berg et al., 2004). In the ovary, VTG is sequestered from the blood stream into the synchronous population of oocytes initiating ovarian recrudescence (Tyler & Sumpter, 1996). During ovarian recrudescence, the GSI can increase by more than 100-fold in some species (Conte et al., 1988; Tyler & Sumpter, 1996). In late vitellogenesis, ovarian aromatase activity begins to decrease back to resting levels which reduces the conversion of T to E2 causing plasma E2 levels to decline to resting levels (Kumar et al., 2000; Trant et al., 1997). Less plasma E2 decreases hepatic synthesis of VTG as the synchronous population of oocytes complete sequestration of VTG from the plasma (Kumar et al., 2000; Trant et al., 1997). Spawning can occur directly upon completion of ovarian recrudescence or following a holding period which can last for several months depending upon the species (Barrett & Munkittrick, 2010). These attributes present a significant challenge to laboratory investigation of reproduction in fishes with group-synchronous oocyte development. Consequently, adverse effects of aromatase inhibition on group-synchronous oocyte development is known only from limited results of in vitro assays and short-term in vivo assays and might not accurately represent responses that could occur in the environment (Afonso et al., 1997; 1999a; 1999b; Beitel et al., 2014; Doering et al., 2019; Marca Pereira et al., 2011). Therefore, the objective of the present study was to identify and employ a suitable laboratory model species of fish to investigate effects of chemical inhibition of aromatase activity on group-synchronous oocyte development.

The western mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) is one species that could represent a suitable laboratory model fish for investigation of effects of chemical inhibition of aromatase activity on group-synchronous oocyte development. Western mosquitofish are relatively small with a maximum size of about 6 cm (Pyke, 2005). They are sexually dimorphic with males easily identified by the presence of a gonopodium, which is used for internal fertilization of the eggs (viviparity) (Pyke, 2005). They are also readily available and easily cultured in captivity (Pyke, 2005). Further, transcript sequences are available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database for many key genes from western mosquitofish and other closely related Gambusia spp. For these reasons, western mosquitofish have been employed to some extent in chemical toxicity testing but have not been used previously to assess effects of aromatase inhibition on group-synchronous oocyte development. The reproductive physiology of western mosquitofish, and other Gambusia spp., has been characterized in detail with ovaries being demonstrated to undergo group-synchronous oocyte development (Edwards et al., 2006; 2010; Hughes, 1985; Koya et al., 2000; 2003; Koya & Kamiya, 2000; Meffe & Snelson, 1993). However, the western mosquitofish can produce multiple clutches per year with a complete reproductive cycle occurring at approximately monthly intervals (Krumholz, 1948; Lloyd et al., 1986). In western mosquitofish, vitellogenesis is initiated when water temperature exceeds 14 °C, but final oocyte maturation only occurs when water temperature exceeds 18 °C (Koya & Kamiya, 2000; Koya et al., 2004; Medlen, 1951). Photoperiod and other environmental cues appear to play a minor role, if any, in initiating vitellogenesis in western mosquitofish (Koya et al., 2004; Medlen, 1951). Since vitellogenesis can be initiated by temperature alone and the reproductive cycle is relatively short, western mosquitofish are more amenable for laboratory reproductive studies than other group-synchronous species (Bon et al., 1997; Olsson et al., 1987).

The specific objective of the present study was to use the western mosquitofish as a laboratory model to investigate adverse effects of chemical aromatase inhibition on group-synchronous oocyte development. Specifically, adult western mosquitofish were exposed to the model nonsteroidal aromatase inhibiting chemical, fadrozole, from the resting stage through to gonadal recrudescence. Temporal changes in numerous reproductive parameters were measured, including GSI, plasma sex steroids, and expression of selected genes in the brain, liver, and gonad that are important for reproduction. This research represents an early step towards better understanding possible impacts of chemical aromatase inhibition on fishes with group-synchronous oocyte development and better defining the taxonomic applicability domain of the AOP.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Fish

Animal research protocols were approved by the on-site Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with Animal Welfare Act regulations and Interagency Research Animal Committee guidelines. Adult western mosquitofish were acquired from a commercial supplier (Osage Catfisheries, Osage Beach, MO, USA) in early spring during which time they had been held at an ambient water temperature of approximately 12 °C while overwintering. Import of western mosquitofish into Minnesota was approved by a Prohibited Invasive Species Permit (permit #437) granted by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Upon arrival at the laboratory, fish were maintained at 12 °C in mixed groups of males and females for several months of quarantine. Fish were fed twice daily ad libitum with newly hatched live brine shrimp (Biomarine Aquafauna, Hawthorne, CA). No evidence of reproduction was observed while the fish were held at 12 °C.

2.2. Reproductive toxicity assay

In western mosquitofish, oocyte development is synchronized within an individual but is not always synchronized between individuals and therefore spawning within a group can occur asynchronously (Edwards et al., 2006). Consequently, the reproduction assay was conducted beginning at the resting stage through the first reproductive cycle of the season, which would be most closely synchronized between individuals. For the assay, 6 adult female western mosquitofish were placed together in 20 L aquaria. Only females were used for the assay because they will undergo vitellogenesis and ovarian recrudescence in the absence of males (Koya et al., 2004). Fish were acclimated for 14 days in replicate aquaria at a water temperature of 12 °C prior to initiating the exposure. During both the acclimation and exposure periods, the aquaria received a continuous flow of sand filtered, UV treated Lake Superior water at a rate of 45 mL/min. The photoperiod was 16:8 hr light:dark. Temperature and dissolved oxygen were monitored daily and remained within ± 1 °C of the target temperature and >60%, respectively. Fish were fed twice daily ad libitum with newly hatched live brine shrimp (Biomarine Aquafauna). The exposure consisted of 3 treatment groups with 13 replicate aquaria per treatment. Solvent-free aqueous solutions of fadrozole were prepared as described previously (Ankley et al., 2002).Treatment groups received nominal water concentrations of 0, 2, and 30 μg fadrozole/L (Chemical Abstracts Service [CAS] 102676-47-1; Novartis, Inc., Summit, NJ). Fadrozole at 2 and 30 μg/L represents approximately the lowest effect concentration and the concentration causing complete reproductive failure in the fathead minnow, respectively (Ankley et al., 2002). Following the 14-day acclimation period, the fadrozole exposure was initiated while still at a water temperature of 12 °C (Figure 1). Prior studies with fathead minnows suggest that plasma concentrations of fadrozole reach steady-state within 24 hrs of exposure (Villeneuve et al., 2013). On exposure day 2 the water temperature was slowly increased over 24 hrs from 12 °C to 18 °C to initiate vitellogenesis (Figure 1). On exposure day 3 the water temperature was again slowly increased over 24 hrs from 18 °C to a final temperature of 25 °C (Figure 1). This temperature change regiment is consistent with other investigations of vitellogenesis in Western mosquitofish (Koya et al., 2000; 2003) as this species exhibits high tolerance to rapid temperature change (Uliano et al., 2010). The water temperature was maintained at 25 °C until completion of the exposure on day 19. This water temperature was selected as the final reproductive temperature to maintain consistency with previous research characterizing the time-course of vitellogenesis in Western mosquitofish (Koya et al., 2000; 2003).

Figure 1.

Diagram showing normal temporal changes in CYP19 expression, plasma E2, plasma VTG, and GSI over the reproductive cycle in western mosquitofish (A) relative to water temperature (B) based on a composite of data collected across several studies of western mosquitofish and supported by knowledge of group-synchronous biology from other fishes (Edwards et al., 2006; Koya et al., 2000; Kumar et al., 2000; Pyke, 2005; Trant et al., 1997). The 4 sampling time-points used in this experiment are highlighted as (1) exposure day -1, (2) exposure day 4, (3) exposure day 12, and (4) exposure day 19 relative to the fadrozole exposure period as indicated (B).

Fish were sampled at 4 time-points: exposure day -1 (12 °C), exposure day 4 (25 °C), exposure day 12 (25 °C), and exposure day 19 (25 °C) (Figure 1). These time-points were chosen to approximately represent pre-vitellogenic resting (day -1), early vitellogenesis (day 4), late vitellogenesis/early ovarian recrudescence (day 12), and late ovarian recrudescence (day 19) (Figure 1). One aquaria per treatment group was sampled on day -1 and considered as replicates because exposure to fadrozole had not yet begun (n = 3 aquaria, n = 18 fish). Four aquaria per treatment group (n = 4 aquaria, n = 24 fish) were sampled on days 4, 12, and 19. During sampling, fish were euthanized in buffered tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222, 100 mg/L buffered with 200 mg NAHCO3/L; Argent, Richmond, WA). Whole fish and excised ovaries were weighted for determination of GSI. Brain, liver, and ovary were excised and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen then stored at −80 °C until analyzed. Blood was collected from the caudal vasculature with a heparinized microhematocrit tube and centrifuged to obtain plasma. Volumes of plasma collected from individual fish were too small to perform all the desired analytical and biochemical measurements. Therefore, plasma from all 6 individuals in each replicate aquaria were pooled to create a composite plasma sample for each replicate of each treatment (n = 4 composite samples). Plasma was stored at −80 °C until analyzed.

2.3. Analytical measurements

Water samples were collected from each replicate aquaria a minimum of twice weekly during the exposure phase. An Agilent 1260 high performance liquid chromatograph (LC) coupled to an Agilent 6410 mass spectrometer (MS) (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) was used to determine the concentrations of fadrozole in water and in plasma as described previously (Doering et al., 2019).

2.4. Biochemical measurements

Plasma concentrations of T and E2 were determined by radioimmunoassay (RIA) according to methods described previously (Jensen et al., 2001). Radioactivity was measured by use of a Tri-Carb 2910 TR liquid scintillation analyser (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA).

2.5. Molecular measurements

Total RNA was extracted from brain, liver, and ovary from 3 randomly selected fish per replicate aquaria per treatment group (n = 12 fish) by use of the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and Tri reagent (Sigma), according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Quality and concentration of the total RNA was determined by use of a Nanodrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Samples were stored at −80 °C until analyzed. Gene-specific quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) primers for aromatase ovarian isoform (cyp19a), aromatase brain isoform (cyp19b), VTG A isoform (vtg-a), VTG B isoform (vtg-b), follicle stimulating hormone receptor (fshr), cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (cyp11a), apolipoprotein A1 (apoa1), and apolipoprotein C1 (apoc1) were designed by use of Primer3 software (Rozen & Skaletsky, 2000) from conserved regions of the nucleotide sequence from western mosquitofish or another Gambusia spp. which were available in the NCBI database (Table 1). Each gene-specific primer pair was validated in western mosquitofish through gel electrophoresis to confirm a single product of the proper size and through a melt curve. Transcript abundance of each gene was measured by use of Power SYBR Green RNA-to-CT (1-step) kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Reactions were performed in duplicate with each 20 μL qPCR reaction containing 20 ng total RNA, 215 nM forward primer, and 215 nM reverse primer. The thermocycling program was set to 48 °C for 30 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min for 40 cycles, 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C 1 min, 95 °C for 15 s. Relative transcript abundance was quantified using gene-specific cDNA standards with six concentrations, following a 10-fold dilution series (1:105-1:1010). Amplification efficiencies ranged from 90.8 to 108.7 %.

Table 1.

Gene specific primers for western mosquitofish used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

| Gene | Accession # | Amplicon Size (bp) | Sequence (5’ to 3’) |

|---|---|---|---|

| cyp19b | KX384597.1 | 133 | Forward: GGAGAAGCTGGATGACGACC Reverse: GATGGAGAGCGTGTCAGGAG |

| cyp19b | DQ865279.1 | 192 | Forward: CTTCACGGCAGACCTCATATT Reverse: CCTATGACGGTGTCTATCTCCT |

| cyp11a | XM_015052070.1 | 205 | Forward: GAACGGTGAAGACTGGAGAAA Reverse: CACCGACTCTAGAGCGTATTT |

| fshr | NM_001201514.1 | 218 | Forward: ATCCACCCAGATGCTTTCAG Reverse: CCATTTCTGGTTAGCCGTATCT |

| apoa1 | XM_008426077.1 | 155 | Forward: GCCCATTGTTGAGTCTGTGC Reverse: CCCTCAGGCTAGTGATCTGC |

| apoc1 | XM_008431168.1 | 148 | Forward: GTCGCATACACAGAGGCTCA Reverse: TCCTGGTGCTCACTGCAAAT |

| vtg-a | AB181835.1 | 199 | Forward: ACCTCCTCTAGCTCTTCATCTC Reverse: CTGAACTGCTGCTGGATCTT |

| vtg-b | AB181836.1 | 197 | Forward: TCACACCAGTTGTCCCATTAG Reverse: GGCCTGTATTCCGTATGTGTAT |

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted by use of SPSS 20 software (Chicago, IL, USA). Normality of each dataset was evaluated by use of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and homogeneity of variance was determined by use of Levene’s test. Data were log-transformed when necessary to meet assumptions of parametric statistics, but non-transformed values are shown in the figures. Significant differences were evaluated by use of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

3.0. RESULTS

3.1. Group-synchronous oocyte development in western mosquitofish

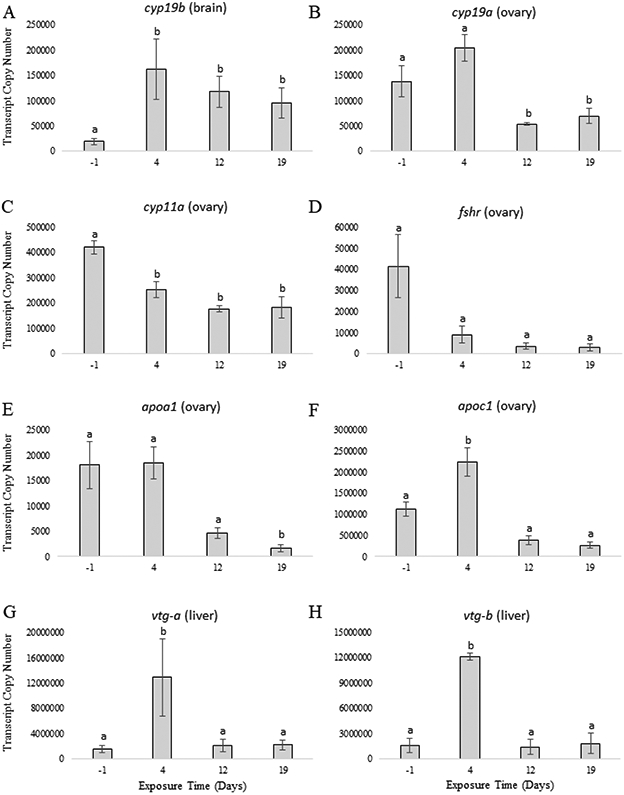

No fadrozole was detected in the water (detection limit = 0.5 μg fadrozole/L) in any control aquaria over the course of the study or in the plasma of any fish from the control treatment (detection limit = 0.25 μg fadrozole/L) (Table 2). Western mosquitofish in the control treatment proceeded through a group-synchronous reproductive cycle following an increase in water temperature from 12 °C to 25 °C as demonstrated through temporal changes in reproductive parameters. No significant differences in plasma E2 or T were detected across sampling time-points, although there was greater plasma E2 on day 4 relative to the other time-points (Figure 2A) and greater plasma T on day -1 relative to the other time-points (Figure 2B). GSI significantly increased from days -1 and 4 to days 12 and 19 (Figure 2C). Temporal changes in gene expression occurred in fish from the control treatment for the investigated reproductive genes (Figure 3), except for fshr where no significant differences were detected across sampling time-points (Figure 3D). A significant increase in expression of cyp19b in brain occurred by day 4 and remained unchanged until day 19 (Figure 3A). No significant difference in expression of cyp19a in ovary was detected between day -1 and day 4, although expression was greatest on day 4, while a significant decrease in expression of cyp19a in ovary occurred by day 12 and remained unchanged until day 19 (Figure 3B). A significant decrease in expression of cyp11a (Figure 3C) and apoa1 (Figure 3E) in ovary occurred by day 4 and remained unchanged until day 19. A significant increase in expression of apoc1 in ovary (Figure 3F), vtg-a in liver (Figure 3G), and vtg-b in liver (Figure 3H) occurred by day 4 and then decreased by day 12 and remained unchanged until day 19.

Table 2.

| Nominal Water (μg/L) | Measured Water (μg/L) | Measured Plasma (μg/L)c | Bioconcentration Factor (BCF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | < 0.50 | < 0.25 | - |

| 2 | 1.9 (± 0.08) | 1.3 (± 0.20) | 0.7 |

| 30 | 31.8 (± 1.4) | 28.1 (± 8.0) | 0.9 |

Standard deviation shown in brackets.

Detection limit was 0.5 μg fadrozole/L for water and 0.25 μg fadrozole/L for plasma.

Average concentration measured in plasma of fish sampled on exposure days 4, 12, and 19.

Figure 2.

(A) Plasma E2 (n = 4), (B) plasma T (n = 4), and (C) GSI (n = 24) in control western mosquitofish at 4 time-points across the reproductive cycle. These 4 time-points represent pre-vitellogenesis resting (exposure day -1; 12 °C), early vitellogenesis (exposure day 4; 25 °C), late-vitellogenesis/early recrudescence (exposure day 12; 25 °C), and recrudescence (exposure day 19; 25 °C) Different letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05). Standard error of the mean (SEM) is shown.

Figure 3.

Gene expression in control western mosquitofish at 4 time-points across the reproductive cycle (n = 12). These 4 time-points represent pre-vitellogenesis resting (exposure day -1; 12 °C), early vitellogenesis (exposure day 4; 25 °C), late-vitellogenesis/early recrudescence (exposure day 12; 25 °C), and recrudescence (exposure day 19; 25 °C). The gene and tissue are indicated above each panel. Different letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05). Standard error of the mean (SEM) is shown.

3.2. Effects of exposure to fadrozole on group-synchronous oocyte development

Water concentrations of fadrozole were close to nominal and did not vary greatly during the exposure (Table 2). The plasma fadrozole concentration did not vary greatly between fish sampled on exposure days 4, 12, and 19 (Table 2). The average bioconcentration factor (BCF) of fadrozole in plasma of western mosquitofish was 0.8 (Table 2) which is comparable to the average BCF of fadrozole measured in plasma of fathead minnow (0.8), Japanese medaka (0.9), and zebrafish (0.2) (Doering et al., 2019; Villeneuve et al., 2013). Exposure of western mosquitofish to 2 μg/L or 30 μg/L of fadrozole beginning during the resting stage and proceeding through to gonadal recrudescence caused temporal changes in reproductive parameters relative to controls. On day 4, plasma E2 was significantly less in western mosquitofish exposed to 30 μg/L of fadrozole relative to fish in the control and 2 μg/L treatments (Figure 4A). However, plasma E2 in fish exposed to 30 μg/L of fadrozole was not statistically different from controls on days 12 or 19; while plasma E2 in fish exposed to 2 μg/L of fadrozole was significantly greater than controls by day 19 (Figure 4A). Plasma T was significantly greater in fish exposed to 2 and 30 μg/L of fadrozole relative to controls on days 4, 12, and 19 with the exception of fish in the 2 μg/L treatment on day 4 (Figure 4B). GSI in fish exposed to 2 and 30 μg/L of fadrozole was not significantly different from controls on days 4 or 12 but was significantly less in fish exposed to 2 μg/L of fadrozole by day 19 (Figure 4C). Expression of cyp19b, fshr, and apoc1 in fish exposed to 2 or 30 μg/L of fadrozole were not statistically different from fish in the controls on days 4, 12, or 19 (Figure 5A; Figure 5D; Figure 5F). Expression of cyp19a and cyp11a in ovary of fish exposed to 2 and 30 μg/L of fadrozole was significantly greater relative to fish in the controls on days 12 and 19 (Figure 5B; Figure 5C). Expression of apoa1 in ovary of fish exposed to 30 μg/L of fadrozole was significantly greater relative to fish in the control and 2 μg/L treatment on day 4, but not on days 12 and 19 (Figure 5E). Expression of vtg-a and vtg-b in liver of fish exposed to 30 μg/L of fadrozole was significantly less relative to fish in the control on day 4, while no significant difference in expression occurred in fish exposed to 2 μg/L (Figure 5G; Figure 5H). Expression of vtg-a and vtg-b in liver of fish exposed to 2 or 30 μg/L of fadrozole were not significantly different from fish in the controls on days 12 or 19 (Figure 5G; Figure 5H).

Figure 4.

(A) Plasma E2 (n = 4), (B) plasma T (n = 4), and (C) GSI (n = 24) in western mosquitofish exposed to fadrozole (FAD) at 4 time-points across the reproductive cycle. These 4 time-points represent pre-vitellogenesis resting (exposure day -1; 12 °C), early vitellogenesis (exposure day 4; 25 °C), late-vitellogenesis/early recrudescence (exposure day 12; 25 °C), and recrudescence (exposure day 19; 25 °C) Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) among treatments at exposure day 4. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) among treatments at exposure day 12. Different Greek letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) among treatments at exposure day 19. Standard error of the mean (SEM) is shown. Data for the 0 μg FAD/L treatment (Figure 2) is reproduced again here for clarity when comparing across treatments.

Figure 5.

Gene expression in western mosquitofish exposed to fadrozole (FAD) at 4 time-points across the reproductive cycle (n = 12). These 4 time-points represent pre-vitellogenesis resting (exposure day -1; 12 °C), early vitellogenesis (exposure day 4; 25 °C), late-vitellogenesis/early recrudescence (exposure day 12; 25 °C), and recrudescence (exposure day 19; 25 °C). The gene and tissue are indicated above each panel. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) among treatments at exposure day 4. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) among treatments at exposure day 12. Different Greek letters indicate significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) among treatments at exposure day 19. Standard error of the mean (SEM) is shown. Data for the 0 μg FAD/L treatment (Figure 3) is reproduced again here for clarity when comparing across treatments.

4. DISCUSSION

An almost complete lack of test data for fishes with group-synchronous oocyte development has resulted in uncertainty regarding sensitivity to and adverse effects of aromatase inhibition which impairs assessments of risk. Therefore, the present study used the western mosquitofish which appears to be a reasonable laboratory model species for investigating aromatase inhibition on group-synchronous oocyte development because vitellogenesis can be initiated by temperature alone and the reproductive cycle is relatively short at less than one month. In prior characterizations of group-synchronous reproductive cycles in this species, an increase in plasma E2 and plasma VTG occurred rapidly, within 24 hrs, at a water temperature of 25 °C, with peak response occurring after approximately 72 hrs (Koya et al., 2003). In these characterizations, GSI increased for approximately two weeks from about 5% at resting to a maximum of about 15% (Koya et al., 2000). Consistent with these prior studies, female western mosquitofish in the control treatment proceeded through a group-synchronous reproductive cycle following an increase in water temperature from 12 °C to 25 °C as demonstrated mainly by an increase in GSI from about 7% at resting to about 12% on day 19, but also through a limited temporal increase and then decrease in other reproductive parameters (Figure 2; Figure 3). The observed increase in reproductive parameters occurred rapidly, by at least day 4, at which time the fish had been at 25 °C for about 24 hrs, and which is consistent with the prior characterizations. At the first sampling time-point on day 4, ovarian cyp19a and plasma E2 had increased but were not significantly different from resting levels (Figure 2), while hepatic vtg transcripts were up-regulated by approximately 10-fold (Figure 3). These relatively small increases in responses limit the confirmation that a dramatic increase in response occurred as would be characteristic of vitellogenesis in a group-synchronous reproductive cycle. However, these results are consistent with the prior characterizations where reproductive parameters began to increase within 24 hrs but didn’t reach their peak until 72 hrs and therefore supports that this time-point represents early vitellogenesis prior to peak response (Figure 1). By the second sampling time-point on day 12 all 3 of these parameters had returned to resting levels and GSI had begun trending upwards (Figure 2; Figure 3). By the end of the exposure on day 19, the GSI had significantly increased from resting levels and was at approximately its expected maximum based on the prior characterizations. This suggests that impacts of chemical aromatase inhibition on GSI, a critical apical reproductive endpoint, should be detectable within a 19-day assay.

In fishes with asynchronous oocyte development, exposure to the model aromatase inhibiting chemical, fadrozole, is associated with a compensatory up-regulation in ovarian cyp19a, a decrease in circulating E2 and VTG, and decreased or cessation in egg production (Ankley et al., 2002; Doering et al., 2019; Villeneuve et al., 2006). Similarly, short-term in vivo assays with coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) demonstrate that fadrozole is capable of decreasing circulating E2 during vitellogenesis in this synchronously spawning fish, but fadrozole did not adversely affect ovarian recrudescence (Afonso et al., 1999a; 1999b). Exposure of western mosquitofish to 2 and 30 μg/L of fadrozole beginning from the resting stage altered the temporal changes in reproductive parameters caused by increased water temperature relative to control fish (Figure 4; Figure 5). In general, this alteration in responses suggested dose-dependency as the responses measured in fish from the 30 μg/L treatment were typically of a greater magnitude relative to responses measured in fish from the 2 μg/L treatment, although responses measured in fish from these 2 treatments were rarely statistically different. Expression of cyp19a in the ovary remained elevated in western mosquitofish from both fadrozole treatment groups until the end of the exposure on day 19, in contrast to fish from the control treatment where expression of cyp19a in the ovary had decreased below resting levels by at least day 12 (Figure 5). However, by day 19, plasma E2 was elevated in fish from both fadrozole treatment groups (Figure 4) which suggests some capacity for compensation. A compensatory response could result through several different mechanisms, but might be caused by a sustained increase in circulating T (Figure 4), a precursor of E2, caused by both a decrease in conversion to E2 by CYP19 and the observed up-regulation in cyp11a (Figure 5) which is involved in the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone, a precursor of T (Uno et al., 2012). One purpose of performing the exposure with western mosquitofish for 19 days was to determine whether fadrozole would delay, but not prevent, completion of a group-synchronous reproductive cycle. However, the observed persistence in elevated expression of cyp19a in the ovary, the lack of a clear up-regulation in expression of vtgs in the liver, and the low GSI together suggest that vitellogenesis was incomplete and that the group-synchronous reproductive cycle was unsuccessful during the assay in fish from either fadrozole treatment (Figure 5), despite the evidence of some compensatory response. This reproductive dysfunction in western mosquitofish exposed to both 2 and 30 μg/L of fadrozole suggests that this species is at least as sensitive to aromatase inhibition by fadrozole in vivo as fathead minnow, Japanese medaka, and zebrafish (Ankley et al., 2002; Doering et al., 2019). High sensitivity of Western mosquitofish to fadrozole is supported by results from in vitro aromatase inhibition assays where CYP19 activity in Western mosquitofish, and most other fishes with group-synchronous oocyte development, is approximately an order of magnitude more sensitive to inhibition by fadrozole relative to the asynchronous laboratory model species (Doering et al., 2019). However, the true extent of the in vivo sensitivity of western mosquitofish to fadrozole remains uncertain because responses from both fadrozole treatments suggest complete reproductive failure during the assay and because GSI was used as the singular measure of reproductive output while fecundity was not directly measured. Effects of aromatase inhibition on fecundity in Western mosquitofish and at lesser concentrations of fadrozole warrants further investigation.

Ovarian atresia is a follicular degeneration and resorptive process that is involved in normal ovarian recrudescence and postovulatory regression in fishes and is often observed in the ovaries of females unable to complete recrudescence due to various environmental stressors (Saidapur, 1978). Ovarian atresia has been previously recorded in fish exposed to various environmental contaminants and could be occurring in the ovaries of western mosquitofish exposed to fadrozole (Janz et al., 1997; Leino et al., 2005; Uchida et al., 2004). Although the specific molecular pathways involved in ovarian atresia in fishes are not completely understood, global transcriptional analysis of ovaries from marine flatfish (Solea senegalensis), a species with group-synchronous oocyte development, has been used to identify transcripts whose expression is tightly correlated with ovaries undergoing atresia (Tingaud-Sequeira et al., 2009). From these previously identified transcriptional biomarkers for ovarian atresia, apoa1 and apoc1 were selected for investigation in ovaries of western mosquitofish because their expression is highly up-regulated in ovaries undergoing atresia but not at other stages of ovarian development (Tingaud-Sequeira et al., 2009). However, although western mosquitofish exposed to 30 μg/L of fadrozole had a significant up-regulation in ovarian APOA1 on day 4 and a trend towards up-regulation in ovarian APOC1 on days 12 and 19 (Figure 5), there was no clear pattern of transcriptional responses that would indicate that ovarian atresia was occurring from exposure to fadrozole. It is possible that ovarian atresia might be a more important response to chemical aromatase inhibition if exposure had begun after the initiation of vitellogenesis during early ovarian recrudescence and not beginning during the resting stage when the ovary is already degenerate.

The present study demonstrates that exposure to aromatase inhibiting chemicals beginning during the resting stage can cause reproductive dysfunction in fishes with group-synchronous oocyte development. This reproductive dysfunction was demonstrated through a compensatory up-regulation in ovarian cyp19a, the lack of a clear increase in plasma E2 and hepatic vtgs, and apparent cessation of ovarian recrudescence as reflected in low GSI. These observed responses are all shared with the better studied fishes with asynchronous oocyte development and are consistent with key events in the AOP linking aromatase inhibition to reproductive dysfunction (Villeneuve, 2016). This supports the applicability of the AOP to both fishes with asynchronous and group-synchronous oocyte development. However, the present study also identified distinct temporal differences in these responses during group-synchronous oocyte development that are not observed in fishes with asynchronous oocyte development. This means that reproductive stage must be carefully considered when evaluating potential for adverse reproductive effects in fishes with group-synchronous oocyte development. It has previously been proposed that seasonality and reproductive stage could be important determinants of susceptibility to chemical aromatase inhibition in fishes, and that fish might not be adversely affected by exposures during certain periods of the reproductive cycle (Beitel et al., 2014). For example, exposure to aromatase inhibiting chemicals solely during stages where ovarian aromatase activity is low, such as during the pre-vitellogenic resting stage or post-vitellogenic ovarian recrudescence, might have no impact on reproductive success. However, the present study investigated exposure to fadrozole over the full reproductive cycle beginning during the resting stage. Consequently, susceptibility to chemical aromatase inhibition during different stages of the reproductive cycle could not be independently assessed but warrants further investigation. Chemicals that can inhibit aromatase activity are frequently detected in aquatic environments in the ng/L to μg/L range (Battaglin et al, 2011, Berenzen et al, 2005, Kahle et al, 2008, Liess & Von Der Ohe, 2005, Lindberg et al, 2010, Stamatis et al, 2010, Wightwick et al, 2012). Although the present study was not specifically designed to assess the possible ecological risks of chemical aromatase inhibition on native fishes with group-synchronous oocyte development, the resultant adverse effects data using western mosquitofish as a laboratory model suggest that exposure to aromatase inhibitors has the potential to cause reproductive dysfunction in a wide range of fishes with both asynchronous and group-synchronous reproductive strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded through the U.S. EPA. Thank you to Kevin Lott for laboratory culture of western mosquitofish. We also thank Dalma Martinovic and Lesley Mills for providing thoughtful review comments on an earlier version of the paper. This paper has been reviewed in accordance with the requirements of the U.S. EPA Office of Research and Development. However, the recommendations made herein do not represent U.S. EPA policy. Mention of products or trade names does not indicate endorsement by the U.S. EPA.

REFERENCES

- Afonso LOB, Campbell PM, Iwama GK, Devlin RH, Donaldson EM (1997). The effect of the aromatase inhibitor fadrozole and two polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons on sex steroid secretion by ovarian follicles of coho salmon. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol 106, 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonso LOB, Iwama GK, Smith J, Donaldson EM (1999a). Effects of the aromatase inhibitor fadrozole on plasma sex steroid secretion and oocyte maturation in female coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) during vitellogenesis. Fish Physiol. Biochem 20, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Afonso LOB, Iwama GK, Smith J, Donaldson EM (1999b). Effects of the aromatase inhibitor fadrozole on plasma sex steroid secretion and ovulation rate in female coho salmon. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol 113, 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley GT, Bennett RS, Erickson RJ, Hoff DJ, Hornung MW, Johnson RD, Mount DR, Nichols JW, Russom CL, Schmieder PK, Serrano JA, Tietge JE, Villeneuve DL (2010). Adverse outcome pathways: A conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 29 (3), 730–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley GT, Blackwell BR, Cavallin JE, Doering JA, Feifarek DJ, Jensen KM, Kahl MD, LaLone CA, Poole ST, Randolph EC, Saari TW, Villeneuve DL (2020). Adverse outcome pathway network-based assessment of the interactive effects of an androgen receptor agonist and an aromatase inhibitor on fish endocrine function. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 39 (4), 913–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley GT, Jensen KM, Durhan EJ, Makynen EA, Butterworth BC, Kahl MD, Villeneuve DL, Linnum A, Gray LE, Cardon M, et al. (2005). Effects of two fungicides with multiple modes of action on reproductive endocrine function in the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Toxicol. Sci 86, 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley GT, Jensen KM, Kahl MD, Makynen EA, Blake LS, Greene KJ, Johnson RD, and Villeneuve DL (2007). Ketoconazole in the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas): Reproductive toxicity and biological compensation. Environ. Toxicol. Sci 26, 1214–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley GT, Johnson RD (2004). Small fish models for identifying and assessing the effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Inst. Lab. Anim. Res. J 45, 469–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley GT, Kahl MD, Jensen KM, Hornung MW, Korte JJ, Makynen EA, and Leino RL (2002). Evaluation of the aromatase inhibitor fadrozole in a short-term reproduction assay with the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Toxicol. Sci 67, 121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley GT, Miller DH, Jensen KM, Villeneuve DL, Martinovic D (2008). Relationship of plasma sex steroid concentrations in female fathead minnows to reproductive success and population status. Aquat. Toxicol 88, 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayobahan SU, Eilebrecht E, Kotthoff M, Baumann L, Eilebrecht S, Teigeler M, Hollert H, Kalkhof S, Schafers C (2019). A combined FSTRA-shotgun proteomics approach to identify molecular changes in zebrafish upon chemical exposure. Sci. Rep 9, 6599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglin W, Sandstrom M, Kuivila K, Kolpin D, Meyer M (2011). Occurrence of azoxystrobin, propiconazole, and selected other fungicides in US streams, 2005-2006. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 218, 307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Beitel SC, Doering JA, Patterson SE, Hecker M (2014). Assessment of the sensitivity of three North American fish species to disruptors of steroidogenesis using in vitro tissue explants. Aquat. Toxicol 152, 273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenzen N, Lentzen-Godding A, Probst M, Schultz H, Schultz R, Liess M (2005). A comparison of predicted and measured levels of runoff-related pesticide concentrations in small lowland streams on a landscrape level. Chemosphere. 58, 683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg AH, Westerlund L, Olsson PE (2004). Regulation of Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) egg shell proteins and vitellogenin during reproduction and in response to 17β-estradiol and cortisol. Gen. Comp. Endocrin 135, 276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon E, Barbe U, Nunez Rodriquez J, Cuisset B, Pelissero C, Sumpter JP, Le Menn F (1997). Plasma vitellogenin levels during the annual reproductive cycle of the female rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): Establishment and validation of an ELISA. Comp. Biochem. Physiol 117B (1), 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke MG, Leatherland JF, Sumpter JP (1984). Seasonal changes in serum testosterone, 11-ketotestosterone, and 17β-estradiol levels in the brown bullhead, Ictalurus nebulosus Lesueur. Can. J. Zool 62, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Celander MC, Goldstone JV, Denslow ND, Iguchi T, Kille P, Meyerhoff RD, Smith BA, Hutchinson TH, and Wheeler JR (2011). Species extrapolation for the 21st century. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 30, 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conolly RB, Ankley GT, Cheng W, Mayo ML, Miller DH, Perkins EJ, Villeneuve DL, Watanabe KH (2017). Quantitative adverse outcome pathways and their application to predictive toxicology. Environ. Sci. Technol 51, 4661–4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte FS, Doroshov SI, Lutes PB, Strange EM (1988). Hatchery manual for the white sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus Richardson with application to other North American Acipenseridae. University of California, Oakland, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Doering JA, Villeneuve DL, Fay KA, Randolph EC, Jensen KM, Kahl MD, LaLone CA, Ankley GT (2019). Differential sensitivity to in vitro inhibition of cytochrome P450 aromatase (CYP19) activity among 18 freshwater fishes. Toxicol. Sci 170 (2), 394–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering JA, Villeneuve DL, Poole ST, Blackwell BR, Jensen KM, Kahl MD, Kittelson AR, Feifarek DJ, Tilton CB, Lalone CA, Ankley GT (2019). Quantitative response-response relationships linking aromatase inhibition to decreased fecundity are conserved across three fishes with asynchronous oocyte development. Environ. Sci. Technol 53 (17), 10470–10478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards TM, Miller HD, Guillette LJ jr. (2006). Water quality influences reproduction in female mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis) from eight Florida springs. Environ. Helth. Persp 114 (1), 69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards TM, Toft G, Guillette LJ Jr. (2010). Seasonal reproductive patterns of female Gambusia holbrooki from two Florida lakes. Sci. Totl. Environ 408, 1569–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes JL (1993). Annual reestablishment of mosquitofish populations in Nebraska. Copeia. 1993, 232–235. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson BA, Trivedi T, Collins N (2000). Annual cycle of energy allocation to growth and reproduction of yellow perch. J. Fish Biol 57, 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Holden MJ, Raitt DFS (1974). Manual of fisheries science. 2. Methods of resource investigation and application. FAO Fish. Tech. Pap. No. 115, Rev. 1, 211 p. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL (1985). Seasonal changes in fecundity and size at 1st reproduction in an Indiana population of the mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis. Am. Midl. Nat 114, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamatsu T, Ohta T, Oshima E, Sakai N (1988). Oogenesis in the medaka Oryzias latipes - stages of oocyte development. Zool. Sci 5, 353–373. [Google Scholar]

- Janz DM, McMaster ME, Munkittrick KR, Van der Kraak G (1997). Elevated ovarian follicular apoptosis and heat shock protein-70 expression in white sucker exposed to bleached kraft pulp mill effluent. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 147, 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KM, Korte JJ, Kahl MD, Pasha MS, Ankley GT (2001). Aspects of basic reproductive biology and endocrinology in the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C 266, 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle M, Buerge IJ, Hauser A, Muller MD, and Poiger T (2008). Azole fungicides: Occurrence and fate in wastewater and surface waters. Environ. Sci. Technol 42, 7193–7200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koya Y, Inoue M, Naruse T, Sawaguchi S (2000). Dynamics of oocyte and embryonic development during ovarian cycle of the viviparous mosquitofish Gambusia affinis. Fish. Sci 66, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Koya Y, Ishikawa S, Sawaguchi S (2004). Effects of temperature and photoperiod on ovarian cycle in the mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis. Jpn. J. Ichthyol 51, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Koya Y, Kamiya E (2000). Environmental regulation of annual reproductive cycle in the mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis. J. Environ. Zool 286, 204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koya Y, Sawaguchi S, Shimizu K, Shimizu A (2003). Endocrine changes during the onset of vitellogenesis in spring in the mosquitofish. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 28, 349–350. [Google Scholar]

- Krumholz LA (1948). Reproduction in the western mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis affinis (Baird & Girard), and its use in mosquito control. Ecol. Monogr 18, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar RS, Ijiri S, Trant JM (2000). Changes in the expression of genes encoding steroidogenic enzymes in the channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) ovary throughout a reproductive cycle. Biol. Repro 63, 1676–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence C (2007). The husbandry of zebrafish (Danio rerio): A review. Aquaculture. 269 (1-4), 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Leino RL, Jensen KM, Ankley GT (2005). Gonadal histology and characteristic histopathology associated with endocrine disruption in the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol 19, 85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liess M, Von Der Ohe P (2005). Analyzing effects of pesticides on invertebrate communities in streams. Environ. Tox. Chem 24 (4), 954–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg RH, Fick J, Tysklind M (2010). Screening of antimycotics in Swedish sewage treatment plants - waters and sludge. Water Res. 44, 649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd LN, Arthington AH, Milton DA (1986). The mosquitofish – a valuable mosquito-control agent or a pest? In: Kitching RL (ed.), The Ecology of Exotic Animals and Plants Some Australian Case Histories. John Wiley & Sons, Brisbane, pp. 6–25. [Google Scholar]

- Malison JA, Procarione LS, Barry TP, Kapuscinski AR, Kayes TB (1994). Endocrine and gonadal changes during the annual reproductive cycle of the freshwater teleost, Stizostedion vitreum. Fish Physiol. Biochem 13 (6), 473–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marca Pereira ML, Wheeler JR, Thorpe KL, Burkhardt-Holm P (2011). Development of an ex vivo brown trout (Salmo trutta fario) gonad culture for assessing chemical effects on steroidogenesis. Aquat. Toxicol 101, 500–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medlen AB (1951). Preliminary observations on the effects of temperature and light upon reproduction in Gambusia affinis. Copeia. 1951, 148–152. [Google Scholar]

- Meffe GK, Snelson FF (1993). Annual lipid cycle in eastern mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki, Poeciliidae) from South Carolina. Copeia. 3, 596–604. [Google Scholar]

- Miller DH, Jensen KM, Villeneuve DL, Jahl MD, Makynen EA, Durhan EJ, Ankley GT (2007). Linkage of biochemical responses to population-level effects: a case study with vitellogenin in the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Environ. Toxicol. Chem 26 (3), 521–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murua H, Saborido-Rey F (2003). Female reproductive strategies of marine fish species in the North Atlantic. J. Northw. Atl. Fish. Sci 33, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson P, Haux C, Forlin L (1987). Variations in hepatic metallothionein, zinc and copper levels during an annual reproductive cycle in rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri. Fish Physiol. Biochem 3 (1), 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyke GH (2005). A review of the biology of Gambusia affinis and G. holbrooki. Revs. Fish Biol. Fish 15, 339–365. [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky HJ (2000). Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In: Krawetz S, Misener S (Eds.), Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology. Humana Press, New Jersey, http://fokker.wi.mit.edu/primer3/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saidapur SK (1978). Follicular atresia in the ovaries of nonmammalian vertebrates. Int. Rev. Cytol 54, 225–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson JT (2006). The steroid hormone biosynthesis pathway as a target for endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Tox. Sci 94, 3–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolness SY, Blanksma CA, Cavallin JE, Churchill JJ, Durhan EJ, Jensen KM, Johnson RD, Kahl MD, Makynen EA, Villeneuve DL, Ankley GT (2013). Propiconazole inhibits steroidogenesis and reproduction in fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Toxicol. Sci 132, 284–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatis N, Hela D, Konstantinou I (2010). Occurrence and removal of fungicides in municipal sewage treatment plant. J. Hazard Mater 175, 829–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tingaud-Sequeira A, Chauvigne F, Lozano J, Agulleiro MJ, Asensio E, Cerda J (2009). New insights into molecular pathways associated with flatfish ovarian development and atresia revealed by transcriptional analysis. BMC Genomics. 10, 434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trant JM, Lehrter J, Gregory T, Nunez S, Wunder J (1997). Expression of cytochrome P450 aromatase in the channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus. J. Steroid Biochem. Molec. Biol 61 (3–6), 393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida D, Yamashita M, Kitano T, Iguchi T (2004). An aromatase inhibitor or high water temperature induce oocyte apoptosis and depletion of P450 aromatase activity in the gonads of genetic female zebrafish during sex-reversal. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Phsyiol 137, 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uliano E, Cataldi M, Carella F, Migliaccio O, Iaccarino D, Agnisola C (2010). Effects of acute changes in salinity and temperature on routine metabolism and nitrogen excretion in gambusia (Gambusia affinis) and zebrafish (Danio rerio). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Molec. Integr. Physiol 157 (3), 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve DL, Breen M, Bencic DC, Cavallin JE, Jensen KM, Makynen EA, Thomas LM, Wehmas LC, Conolly RB, Ankley GT (2013). Developing predictive approaches to characterize adaptive responses of the reproductive endocrine axis to aromatase inhibition: I. data generation in a small fish model. Toxicol. Sci 133 (2), 25–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uno T, Ishizuka M, Itakura T (2012). Cytochrome P450 (CYP) in fish. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol 34 (1), 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve DL (2016). “Adverse outcome pathway on aromatase inhibition leading to reproductive dysfunction (in fish)”, OECD Series on Adverse Outcome Pathways, No. 4, OECD Publishing, Paris, 10.1787/5jlsv05mx433-en. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve DL, Knoebl I, Kahl MD, Jensen KM, Hammermeister DE, Greene KJ, Blake LS, Ankley GT (2006). Relationship between brain and ovary aromatase activity and isoform-specific aromatase mRNA expression in the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Aquat. Toxicol 76, 353–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villeneuve DL, Mueller ND, Martinovic D, Makynen EA, Kahl MD, Jensen KM, Durhan EJ, Cavallin JE, Bencic D, Ankley GT (2009). Direct effects, compensation, and recovery in female fathead minnows exposed to a model aromatase inhibitor. Environ. Health Perspect 117, 624–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinggaard AM, Hnida C, Breinholt V, Larsen JC (2000). Screening of selected pesticides for inhibition of CYP19 aromatase activity in vitro. Toxicol. In Vitro 14, 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RA, Selman K (1981). Cellular and dynamic aspects of oocyte growth in teleosts. Amer. Zool 21, 325–343. [Google Scholar]

- Wightwick AM, Bui AD, Zhang P, Rose G, Allinson M, Myeres JH, Reichman SM, Menzies NW, Pettigrove V, Allinson G (2012). Environmental fate of fungicides in surface waters of a horticultural-production catchment in southeastern Australia. Arch. Environ. Cont. Toxicol 62 (3), 380–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wourms JP (1981). Viviparity: the maternal-fetal relationship in fishes. Amer. Zool 21, 473–515. [Google Scholar]