Abstract

During the current formidable COVID-19 pandemic, it is appealing to address ideas that may invoke therapeutic interventions. Clotting disorders are well recognized in patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), which lead to severe complications that worsen the prognosis in these subjects.

Increasing evidence implicate Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) and Heparanase in various diseases and pathologies, including hypercoagulability states. Moreover, HSPGs and Heparanase are involved in several viral infections, in which they enhance cell entry and release of the viruses.

Herein we discuss the molecular involvement of HSPGs and heparanase in SARS-CoV-2 infection, namely cell entry and release, and the accompanied coagulopathy complications, which assumedly could be blocked by heparanase inhibitors such as Heparin and Pixatimod.

Keywords: Coagulopathy, COVID-19, Heparanase, SARS-COV-2

Background

In December 2019, a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), was described in consecutive cases in Wuhan, China, and later defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, following a rapid worldwide spread. It is well established that SARS-CoV-2 causes multiple serious complications, where the most prominent are severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) as well as multiple organ dysfunction including heart and kidney failure and coagulopathy [1–4]. While the deleterious impact of SARS-CoV-2 on pulmonary, cardiac and renal systems has been studied extensively, the adverse effects of this virus on coagulation process is still underestimated.

COVID-19 and coagulation

Patients with COVID-19 exhibit clotting disorders that adversely affect the prognosis of the disease, and result in higher mortality rates [5–7]. Numerous studies have shown that abnormal coagulation markers, particularly markedly elevated d-dimer, fibrin degradation product (FDP), prolonged prothrombin time, and thrombocytopenia are common in severe patients or non-survivors of COVID-19 [8,9]. Indeed, patients infected by this novel coronavirus are at higher risk for overt disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [1,8,10]. The pathogenesis of hypercoagulability in COVID-19 is not completely understood. However, excessive systemic inflammatory process, platelet activation, blood stasis in immobilized patients, and endothelial dysfunction are among possible etiologic factors that may induce coagulation abnormalities in COVID-19 patients [11–15]. Recent studies (some are observational) had documented lower mortality rate in COVID-19 patients who received anticoagulants in different regimens and doses—both prophylactic and treatment [16].

Similar dysregulations of coagulation system manifested in other coronavirus infections, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [17], suggesting a common downstream pathway underlying COVID-19-induced serious coagulation complication. Unfortunately, the mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon are poorly characterized. One of the potential systems that may play a crucial role in the exaggerated coagulation characterizing COVID-19 is the Heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) and Heparanase system. In this commentary, we will refer to potential evidences about the involvement of HSPGs and heparanase in COVID-19-induced coagulopathy, infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 and viral cell release.

HSPGs and heparanase

HSPGs are ubiquitous constituents of the cell surface and the extracellular matrix (ECM). These macromolecules are largely responsible for binding various proteins, hormones, cytokines, and growth factors to their binding sites on the cell surface, where they exert cardinal functions related to cell–ECM interactions [18–20]. Heparanase, an endo-β-d-glucuronidase, is the only enzyme in mammals that degrades heparan sulfate (HS) chains of HSPGs [21–24]. Heparanase is involved in a wide variety of pathological processes and diseases, where elevated levels of heparanase were demonstrated, including inflammatory and infectious processes [25,26]. In addition, higher heparanase levels were measured in several malignancies [27–30], where the higher abundance of heparanase was associated with more aggressive and advanced disease, besides the occurrence of more disease-related complications [31].

Heparanase and coagulation

Tissue factor (TF), a transmembrane protein, is the main cellular initiator of blood coagulation, where it is expressed in most body cells except blood and endothelial cells. However, in certain conditions associated with high levels of angiotensin II, TF expression is evident also in endothelial cells [33]. TF functions as a receptor and cofactor of plasma factor VII, where together they activate factor X and subsequently the coagulation cascade upon disturbance of vascular integrity [34]. TF pathway inhibitor (TFPI), a multivalent Kunitz-type plasma proteinase inhibitor, is the only endogenous modulator of TF, and is localized to cell surface of endothelial and tumor cells. Several studies showed increased plasma TFPI concentrations in myocardial infarction patients [35,36] and disseminated intravascular coagulation [37].

Degradation of HS by heparanase results in ECM remodeling and release of numerous sequestered components involved in several physiological and pathophysiological processes including blood coagulation [38]. For instance, overexpressing heparanase by transfected cells or adding exogenous heparanase was accompanied by increased levels of TFPI in cell medium [39]. Likewise, heparanase transgenic mice have higher TFPI concentration in their plasma as compared with wildtype (WT) mice [39]. Another set of experiments demonstrated that TFPI release from cell surface following heparanase addition correlated with enhanced TF activity [19]. Moreover, the same research group demonstrated that heparanase directly interacts with TF, thus facilitating factor Xa formation in the presence of TF/VIIa complex. Interestingly, heparin administration provoked disruption of TF–heparanase interaction and eventually abolished the pro-coagulant effects of heparanase, indicating another aspect of heparin anticoagulant activity, apart from enhancing anti-thrombin activity [40]. Based on former reports, the effect of heparin on heparanase is expected to be also applicable for other compounds, including low-molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) and other derivatives [41–43].

Considering the platelets, the essential component in thrombus formation, thrombin formed following activation of the coagulation system was shown to be further inducing heparanase release from platelets [44]. Cui et al. demonstrated that platelets of heparanase transgenic mice had a stronger adhesion activity as compared with WT mice [45], emphasizing heparanase pro-coagulant effect.

Collectively, independent of its enzymatic activity, heparanase was shown to augment coagulation by induction of TF expression and activity [19], increasing TFPI dissociation from cell surface [39], and directly interacting with TF [40] (Figure 1), thus heparanase inhibition is supposed to attenuate these effects and eventually interfere with its procoagulant effects.

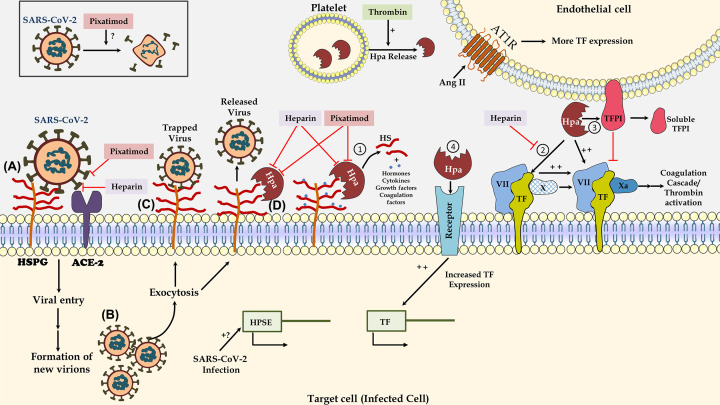

Figure 1. Involvement of heparanase and HSPG in SARS-CoV-2 infection and coagulation.

(A) SARS-CoV-2 binds to HSPGs thus facilitating its interaction with its homing receptor, namely ACE2, on cell surface of the infected cell. (B) Subsequently, the virus is internalized into the cell where it utilizes the host cells’ machinery in order to amplify itself and eventually newly replicated viruses are released. (C) Released viruses are trapped by HSPGs which hinder their ability to spread to neighboring cells. However, (D) enhanced Heparanase (Hpa) enzymatic activity induces HS degradation thus resulting into viral release and spread. Abbreviation: ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2.

Heparanase acts as pro-coagulant in several ways: (1) Following heparanase enzymatic activity, HS is cleaved and the anchored components including coagulation factors are released. (2) Heparanase directly interact with TF, thus facilitating factor Xa formation in the presence of TF/VIIa complex. (3) Heparanase interaction with TFPI, a TF modulator, on endothelial cells results in TFPI release from cell surface, thus eliminating its TF inhibition, and finally, (4) Heparanase induces TF expression. Thrombin induces platelet heparanase release and so augmenting coagulation. Circulating Angiotensin II by binding to AT1 receptor leads to up-regulation of TF expression on endothelial cells.

HS memetic molecules, such as Heparin and Pixatimod, inhibit heparanase along pro-coagulation activity. Moreover, these inhibitors interact with RBD on S1 of SARS-CoV-2 thus block viral cell entry. Virucidal activity of Pixatimod, verified in several viral infections, is still questionable in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although many viral infections results in overexpression of heparanase, this still vague in SARS-CoV-2 infections. Abbreviation: RBD, receptor-binding domain.

Heparanase and HSPGs in viral infection (including coronaviruses)

In addition to their natural function in binding a variety of extracellular ligands, HSPGs serve as a binding receptor for multiple human viruses, including coronaviruses [46–51], making it a target of many studies aiming at blocking this initial interaction, thus impede viral entry [52–55].

Although it is a member of α-coronavirus family, human coronavirus NL63 (HcoV-NL63) was shown to bind HSPG on cell surface, thus enhancing the virus infection [56]. Moreover, it has been reported that other coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-1, employ HSPG for adhesion and cell entry [57–59]. These findings suggest that cell surface HS increases viral density at the cell surface and facilitate the interaction between CoV-NL63 or SARS-CoV, and Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2), the homing receptor for these viruses and their cellular entry [60].

Similar to HSPG, heparanase is deeply involved in viral infection and release. Most studies in this context were performed on herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) infection. Subsequent to HSV-1 infection, HS levels on cell surfaces were dramatically decreased, along heparanase up-regulation [61]. Similar observations were detected in HSV-2 infection [62] and a variety of other viral strains [63–65].

A recent study showed that knockdown of heparanase by using shRNA in mouse and human corneal epithelial cells resulted in significant decrease in HSV-1 release. Seemingly, overexpression of heparanase in these systems resulted in profound viral release [61]. Influenza virus uses analogous mechanisms, where it encodes its own neuraminidase enzyme that facilitates viral detachment and spread after cleaving cell surface sialic acid residues [66]. This observation is contrary to HSV-1 that has no similar enzyme capable of degrading HS, but instead drives the host cell to express more heparanase.

Concerning SARS-CoV-2, a recent study by Buijsers et al. demonstrated higher circulatory heparanase levels and activity in COVID-19 patients as compared with healthy controls [32]. Moreover, these authors found that the disease severity was positively correlated with serum levels of heparanase, HS and IL-6 [32]. Another study by Clausen et al. provided evidence that HSPGs enhance the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2 through the receptor-binding domain (RBD), and heparin and other anticoagulant agents blocked this interaction [67]. However, additional studies are needed in this context.

Collectively, HSPGs and heparanase are shown to be implicated in the pathogenesis of several unrelated viruses including coronaviruses infections. Given that heparanase overexpression was detected in many unrelated viral systems and recently in COVID-19 [32], this may indicate that up-regulation of heparanase is a common strategy among viral species to increase spread and transmission, and the most important point is that this strategy is already confirmed to be adopted by SARS-CoV-2.

Heparanase inhibition as a COVID-19 therapeutic maneuver

After saying that, heparanase inhibition using HS mimicking compounds, anticoagulant heparin, or any other inhibitors, may abolish the deleterious effects of heparanase and HSPGs both on coagulation system, by interfering with TF–heparanase interaction, and blocking viral–cell attachment and cell-to-cell spread.

In this context, heparin, a highly sulfated form of HS that inhibits HS degradation by heparanase, blocked cell binding and invasion by SARS-CoV-2, as it bound to spike (S) 1 RBD leading to conformational change [68]. Noteworthy, sequence analysis of the glycosylated S protein of SARS-CoV-2 revealed that RBD of S1 contained HS-binding sites [69–71]. Similarly, heparin was previously shown to partially block infectivity of SARS-associated coronavirus strain HSR1 [72].

At the clinical level, administration of heparin or LMWH (Enoxaparin) to COVID-19 patients improved their physical condition and survival rate [73]. In a study that included 449 severe COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, prophylactic dose heparin therapy significantly reduced mortality [74]. More specifically, Buijsers et al. showed that prophylactic LMWH reduced heparanase activity in COVID-19 patients [32], a finding that may explain the reduction in SARS-CoV-2 entry to cells following this treatment. Another study that supports this notion is the study by Billet et al. who demonstrated that administration of enoxaparin, unfractionated heparin, and apixaban to severe cases of COVID-19 reduced the mortality rate, most probably due to lower thromboembolic complications, while it could be acceptable to postulate a role of inhibiting heparanase activity in these patients [75].

Pixatimod (PG545), an HS memetic compound, is known as a potent heparanase inhibitor [76]. Apart from its anticancer [77,78], anti-inflammatory [25,79,80], antioxidative [81], and anti-atherosclerotic [82] activities, Pixatimod was previously shown to have antiviral activity to a number of viruses that utilize HS as binding and entry receptor [83–86]. In addition, Pixatimod was shown to have virucidal activity on HSV-1, where viral lipid envelope is disrupted by its lipophilic steroid side chain [84,87].

Interestingly, Pixatimod was recently demonstrated to interact with RBD of S1 of SARS-CoV-2 and thus inhibited viral attachment and invasion in ACE2-expressing vero-cells [88]. Since Pixatimod strongly inhibits heparanase, these results support a deleterious role of this enzyme in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 manifestations, especially coagulopathy, and suggest a therapeutic potential of Heparanase inhibitors as antiviral and anticoagulative agents during this disease state. NCT identifier search revealed no studies dealing with the effect of Pixatimod on COVID-19 patients. Additional heparanase inhibitors are under clinical and basic science research, like SST0001, but NCT identifier search revealed no studies for these compounds in COVID-19 patients. Nevertheless, as for 26 April 2021, we found 132 ongoing (129)/completed (n=3) studies that deal with the effects of different anticoagulants on COVID-19 subjects, and included unfractionated heparin, LMWHs, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)—namely Rivaroxaban (11 studies), Apixaban (7 studies), and Edoxaban (1 study).

In conclusion, herein we summarized the current knowledge regarding the role of heparanase in the pathogenesis of several diseases and the favorable effect of its inhibition in a wide variety of pathologic processes. It is tempting to explore potential role of heparanase in these clinical settings including COVID-19, and to examine the effect of heparanase inhibition in SARS-CoV2-infected subjects, which might be beneficial to heal coagulation system and to attenuate viral attachment and spread, and subsequently to improve the prognosis of infected subjects.

Abbreviations

- ACE2

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- HSPG

heparan sulfate proteoglycan

- HSV-1

herpes simplex virus-1

- LMWH

low-molecular weight heparin

- RBD

receptor-binding domain

- SARS-CoV

severe acute respiratory syndrome -corona virus

- TF

tissue factor

- TFPI

tissue factor pathway inhibitor

- WT

wild-type

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in the review.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that there are no sources of funding to be acknowledged.

References

- 1.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y.et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1708–1720 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhmerov A. and Marban E. (2020) COVID-19 and the heart. Circ. Res. 126, 1443–1455 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan L., Chaudhary K., Saha A.et al. (2020) Acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. medRxiv, Version 1. medRxiv Preprint. 2020 May 8, 10.1101/2020.05.04.20090944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renu K., Prasanna P.L. and Valsala Gopalakrishnan A. (2020) Coronaviruses pathogenesis, comorbidities and multi-organ damage - a review. Life Sci. 255, 117839 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou B., She J.Q., Wang Y.D. and Ma X.C. (2020) Venous thrombosis and arteriosclerosis obliterans of lower extremities in a very severe patient with 2019 novel coronavirus disease: a case report. J. Thromb. Thrombolys. 50, 229–232 10.1007/s11239-020-02084-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S.et al. (2020) Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, e38 10.1056/NEJMc2007575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D.et al. (2020) COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 75, 2950–2973 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang N., Li D., Wang X. and Sun Z. (2020) Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 18, 844–847 10.1111/jth.14768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lippi G., Plebani M. and Henry B.M. (2020) Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta 506, 145–148 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y.D., Zhang S.P., Wei Q.Z.et al. (2020) COVID-19 complicated with DIC: 2 cases report and literatures review. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 41, 245–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Castillo-Garcia S., Minguito-Carazo C., Echarte J.C.et al. (2020) A case report of arterial and venous thromboembolism in a patient with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 4, 1–6 10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levi M. (2018) Pathogenesis and diagnosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 40, 15–20 10.1111/ijlh.12830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lodigiani C., Iapichino G., Carenzo L.et al. (2020) Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb. Res. 191, 9–14 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miesbach W. and Makris M. (2020) COVID-19: coagulopathy, risk of thrombosis, and the rationale for anticoagulation. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 26, 1076029620938149 10.1177/1076029620938149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wichmann D., Sperhake J.P., Lutgehetmann M.et al. (2020) Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 173, 268–277 10.7326/M20-2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denas G., Gennaro N., Ferroni E.et al. (2021) Reduction in all-cause mortality in COVID-19 patients on chronic oral anticoagulation: a population-based propensity score matched study. Int. J. Cardiol. 329, 266–269 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giannis D., Ziogas I.A. and Gianni P. (2020) Coagulation disorders in coronavirus infected patients: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and lessons from the past. J. Clin. Virol. 127, 104362 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernfield M., Gotte M., Park P.W.et al. (1999) Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 729–777 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadir Y., Brenner B., Zetser A.et al. (2006) Heparanase induces tissue factor expression in vascular endothelial and cancer cells. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 2443–2451 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02212.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasisekharan R., Shriver Z., Venkataraman G. and Narayanasami U. (2002) Roles of heparan-sulphate glycosaminoglycans in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 521–528 10.1038/nrc842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Hoven M.J., Rops A.L., Bakker M.A.et al. (2006) Increased expression of heparanase in overt diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 70, 2100–2108 10.1038/sj.ki.5001985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rops A.L., van den Hoven M.J., Veldman B.A.et al. (2012) Urinary heparanase activity in patients with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 27, 2853–2861 10.1093/ndt/gfr732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shafat I., Agbaria A., Boaz M.et al. (2012) Elevated urine heparanase levels are associated with proteinuria and decreased renal allograft function. PLoS ONE 7, e44076 10.1371/journal.pone.0044076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shafat I., Ilan N., Zoabi S., Vlodavsky I. and Nakhoul F. (2011) Heparanase levels are elevated in the urine and plasma of type 2 diabetes patients and associate with blood glucose levels. PLoS ONE 6, e17312 10.1371/journal.pone.0017312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khamaysi I., Singh P., Nasser S.et al. (2017) The role of heparanase in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis: a potential therapeutic target. Sci. Rep. 7, 715 10.1038/s41598-017-00715-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L., Huang X., Kong G.et al. (2016) Ulinastatin attenuates pulmonary endothelial glycocalyx damage and inhibits endothelial heparanase activity in LPS-induced ARDS. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 478, 669–675 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barash U., Lapidot M., Zohar Y.et al. (2018) Involvement of heparanase in the pathogenesis of mesothelioma: basic aspects and clinical applications. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110, 1102–1114 10.1093/jnci/djy032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pisano C., Vlodavsky I., Ilan N. and Zunino F. (2014) The potential of heparanase as a therapeutic target in cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 89, 12–19 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinhal M.A.S., Almeida M.C.L., Costa A.S., Theodoro T.R., Serrano R.L. and Machado C.D.S. (2016) Expression of heparanase in basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. An. Bras. Dermatol. 91, 595–600 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kazarin O., Ilan N., Naroditzky I., Ben-Itzhak O., Vlodavsky I. and Bar-Sela G. (2014) Expression of heparanase in soft tissue sarcomas of adults. J. Exp. Clin. Canc. Res. 33, 39 10.1186/1756-9966-33-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heyman B. and Yang Y.P. (2016) Mechanisms of heparanase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Exp. Hematol. 44, 1002–1012 10.1016/j.exphem.2016.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buijsers B., Yanginlar C., de Nooijer A.et al. (2020) Increased plasma heparanase activity in COVID-19 patients. Front. Immunol. 11, 575047 10.3389/fimmu.2020.575047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dielis A.W., Smid M., Spronk H.M.et al. (2005) The prothrombotic paradox of hypertension: role of the renin-angiotensin and kallikrein-kinin systems. Hypertension 46, 1236–1242 10.1161/01.HYP.0000193538.20705.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camerer E., Kolsto A.B. and Prydz H. (1996) Cell biology of tissue factor, the principal initiator of blood coagulation. Thromb. Res. 81, 1–41 10.1016/0049-3848(95)00209-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamikura Y., Wada H., Yamada A.et al. (1997) Increased tissue factor pathway inhibitor in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Hematol. 55, 183–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winckers K., Siegerink B., Duckers C.et al. (2011) Increased tissue factor pathway inhibitor activity is associated with myocardial infarction in young women: results from the RATIO study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 9, 2243–2250 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04497.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asakura H., Ontachi Y., Mizutani T.et al. (2001) Elevated levels of free tissue factor pathway inhibitor antigen in cases of disseminated intravascular coagulation caused by various underlying diseases. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 12, 1–8 10.1097/00001721-200101000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin H. and Cui M. (2018) New advances of heparanase and heparanase-2 in human diseases. Arch. Med. Res. 49, 423–429 10.1016/j.arcmed.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nadir Y., Brenner B., Gingis-Velitski S.et al. (2008) Heparanase induces tissue factor pathway inhibitor expression and extracellular accumulation in endothelial and tumor cells. Thromb. Haemost. 99, 133–141 10.1055/s-0037-1608919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nadir Y., Brenner B., Fux L., Shafat I., Attias J. and Vlodavsky I. (2010) Heparanase enhances the generation of activated factor X in the presence of tissue factor and activated factor VII. Haematologica 95, 1927–1934 10.3324/haematol.2010.023713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Labarrere C.A., Pitts D., Halbrook H. and Faulk W.P. (1992) Natural anticoagulant pathways in normal and transplanted human hearts. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 11, 342–347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Agostini A.I., Watkins S.C., Slayter H.S., Youssoufian H. and Rosenberg R.D. (1990) Localization of anticoagulantly active heparan sulfate proteoglycans in vascular endothelium: antithrombin binding on cultured endothelial cells and perfused rat aorta. J. Cell Biol. 111, 1293–1304 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iozzo R.V. (2005) Basement membrane proteoglycans: from cellar to ceiling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 646–656 10.1038/nrm1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tatour M., Shapira M., Axelman E.et al. (2017) Thrombin is a selective inducer of heparanase release from platelets and granulocytes via protease-activated receptor-1. Thromb. Haemost. 117, 1391–1401 10.1160/TH16-10-0766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cui H., Tan Y.X., Osterholm C.et al. (2016) Heparanase expression upregulates platelet adhesion activity and thrombogenicity. Oncotarget 7, 39486–39496 10.18632/oncotarget.8960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shukla D. and Spear P.G. (2001) Herpesviruses and heparan sulfate: an intimate relationship in aid of viral entry. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 503–510 10.1172/JCI200113799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roderiquez G., Oravecz T., Yanagishita M., Bou-Habib D.C., Mostowski H. and Norcross M.A. (1995) Mediation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 binding by interaction of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans with the V3 region of envelope gp120-gp41. J. Virol. 69, 2233–2239 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2233-2239.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giroglou T., Florin L., Schafer F., Streeck R.E. and Sapp M. (2001) Human papillomavirus infection requires cell surface heparan sulfate. J. Virol. 75, 1565–1570 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1565-1570.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feldman S.A., Audet S. and Beeler J.A. (2000) The fusion glycoprotein of human respiratory syncytial virus facilitates virus attachment and infectivity via an interaction with cellular heparan sulfate. J. Virol. 74, 6442–6447 10.1128/JVI.74.14.6442-6447.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Y., Maguire T., Hileman R.E.et al. (1997) Dengue virus infectivity depends on envelope protein binding to target cell heparan sulfate. Nat. Med. 3, 866–871 10.1038/nm0897-866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barth H., Schafer C., Adah M.I.et al. (2003) Cellular binding of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E2 requires cell surface heparan sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41003–41012 10.1074/jbc.M302267200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dogra P., Martin E.B., Williams A.et al. (2015) Novel heparan sulfate-binding peptides for blocking herpesvirus entry. PLoS ONE 10, e0126239 10.1371/journal.pone.0126239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jaishankar D., Yakoub A.M., Bogdanov A., Valyi-Nagy T. and Shukla D. (2015) Characterization of a proteolytically stable D-peptide that suppresses herpes simplex virus 1 infection: implications for the development of entry-based antiviral therapy. J. Virol. 89, 1932–1938 10.1128/JVI.02979-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jaishankar D., Buhrman J.S., Valyi-Nagy T., Gemeinhart R.A. and Shukla D. (2016) Extended release of an anti-heparan sulfate peptide from a contact lens suppresses corneal herpes simplex virus-1 infection. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57, 169–180 10.1167/iovs.15-18365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tiwari V., Liu J., Valyi-Nagy T. and Shukla D. (2011) Anti-heparan sulfate peptides that block herpes simplex virus infection in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 25406–25415 10.1074/jbc.M110.201103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Milewska A., Zarebski M., Nowak P., Stozek K., Potempa J. and Pyrc K. (2014) Human coronavirus NL63 utilizes heparan sulfate proteoglycans for attachment to target cells. J. Virol. 88, 13221–13230 10.1128/JVI.02078-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lang J., Yang N., Deng J.et al. (2011) Inhibition of SARS pseudovirus cell entry by lactoferrin binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. PLoS ONE 6, e23710 10.1371/journal.pone.0023710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Madu I.G., Chu V.C., Lee H., Regan A.D., Bauman B.E. and Whittaker G.R. (2007) Heparan sulfate is a selective attachment factor for the avian coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus beaudette. Avian Dis. 51, 45–51 10.1637/0005-2086(2007)051[0045:HSIASA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watanabe R., Sawicki S.G. and Taguchi F. (2007) Heparan sulfate is a binding molecule but not a receptor for CEACAM1-independent infection of murine coronavirus. Virology 366, 16–22 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aquino R.S. and Park P.W. (2016) Glycosaminoglycans and infection. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 21, 1260–1277 10.2741/4455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hadigal S.R., Agelidis A.M., Karasneh G.A.et al. (2015) Heparanase is a host enzyme required for herpes simplex virus-1 release from cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 6985 10.1038/ncomms7985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hopkins J., Yadavalli T., Agelidis A.M. and Shukla D. (2018) Host enzymes heparanase and cathepsin L promote herpes simplex virus 2 release from cells. J. Virol. 92, e01179–18 10.1128/JVI.01179-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khanna M., Ranasinghe C., Browne A.M., Li J.P., Vlodaysky I. and Parish C.R. (2019) Is host heparanase required for the rapid spread of heparan sulfate binding viruses? Virology 529, 1–6 10.1016/j.virol.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guo C.H., Zhu Z.B., Wang X.Y., Chen Y.S. and Liu X.H. (2017) Pyrithione inhibits porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication through interfering with NF-B-K and heparanase. Vet. Microbiol. 201, 231–239 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo C., Zhu Z., Guo Y.et al. (2017) Heparanase upregulation contributes to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus release. J. Virol. 91, e0025–17 10.1128/JVI.00625-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Air G.M. and Laver W.G. (1989) The neuraminidase of influenza virus. Proteins 6, 341–356 10.1002/prot.340060402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clausen T.M., Sandoval D.R., Spliid C.B.et al. (2020) SARS-CoV-2 infection depends on cellular heparan sulfate and ACE2. Cell 183, 1043.e1015–1057.e1015 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mycroft-West C.J., Su D., Pagani I.et al. (2020) Heparin inhibits cellular invasion by SARS-CoV-2: structural dependence of the interaction of the surface protein (spike) S1 receptor binding domain with heparin. Thromb. Haemost. 120, 1700–1715 10.1055/s-0040-1721319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S.et al. (2020) Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367, 1260–1263 10.1126/science.abb2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shang J., Ye G., Shi K.et al. (2020) Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 581, 221–224 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lan J., Ge J., Yu J.et al. (2020) Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 581, 215–220 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vicenzi E., Canducci F., Pinna D.et al. (2004) Coronaviridae and SARS-associated coronavirus strain HSR1. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 413–418 10.3201/eid1003.030683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ayerbe L., Risco C. and Ayis S. (2020) The association between treatment with heparin and survival in patients with Covid-19. J. Thromb Thrombolys. 50, 298–301 10.1007/s11239-020-02162-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J.L., Li D.J. and Sun Z.Y. (2020) Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 18, 1094–1099 10.1111/jth.14817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Billett H.H., Reyes-Gil M., Szymanski J.et al. (2020) Anticoagulation in COVID-19: effect of enoxaparin, heparin, and apixaban on mortality. Thromb. Haemost. 120, 1691–1699 10.1055/s-0040-1720978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hammond E. and Dredge K. (2020) Heparanase inhibition by pixatimod (PG545): basic aspects and future perspectives. In Heparanase: From Basic Research to Clinical Applications(Vlodavsky I., Sanderson R.D. and Ilan N., eds), pp. 539–565, Springer International Publishing, Cham: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ferro V., Liu L., Johnstone K.D.et al. (2012) Discovery of PG545: a highly potent and simultaneous inhibitor of angiogenesis, tumor growth, and metastasis. J. Med. Chem. 55, 3804–3813 10.1021/jm201708h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dredge K., Hammond E., Handley P.et al. (2011) PG545, a dual heparanase and angiogenesis inhibitor, induces potent anti-tumour and anti-metastatic efficacy in preclinical models. Br. J. Cancer 104, 635–642 10.1038/bjc.2011.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koliesnik I.O., Kuipers H.F., Medina C.O.et al. (2020) The heparan sulfate mimetic PG545 modulates T cell responses and prevents delayed-type hypersensitivity. Front. Immunol. 11, 132 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abassi Z., Hamoud S., Hassan A.et al. (2017) Involvement of heparanase in the pathogenesis of acute kidney injury: nephroprotective effect of PG545. Oncotarget 8, 34191–34204 10.18632/oncotarget.16573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hamoud S., Shekh Muhammad R., Abu-Saleh N., Hassan A., Zohar Y. and Hayek T. (2017) Heparanase inhibition reduces glucose levels, blood pressure, and oxidative stress in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Biomed Res. Int. 2017, 7357495 10.1155/2017/7357495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Muhammad R.S., Abu-Saleh N., Kinaneh S.et al. (2018) Heparanase inhibition attenuates atherosclerosis progression and liver steatosis in E0 mice. Atherosclerosis 276, 155–162 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Supramaniam A., Liu X., Ferro V. and Herrero L.J. (2018) Prophylactic antiheparanase activity by PG545 is antiviral in vitro and protects against Ross River virus disease in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62, e01959–17 10.1128/AAC.01959-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Said J.S., Trybala E., Gorander S.et al. (2016) The cholestanol-conjugated sulfated oligosaccharide PG545 disrupts the lipid envelope of herpes simplex virus particles. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 1049–1057 10.1128/AAC.02132-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Said J., Trybala E., Andersson E.et al. (2010) Lipophile-conjugated sulfated oligosaccharides as novel microbicides against HIV-1. Antiviral Res. 86, 286–295 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lundin A., Bergstrom T., Andrighetti-Frohner C.R., Bendrioua L., Ferro V. and Trybala E. (2012) Potent anti-respiratory syncytial virus activity of a cholestanol-sulfated tetrasaccharide conjugate. Antiviral Res. 93, 101–109 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ekblad M., Adamiak B., Bergstrom T.et al. (2010) A highly lipophilic sulfated tetrasaccharide glycoside related to muparfostat (PI-88) exhibits virucidal activity against herpes simplex virus. Antiviral Res. 86, 196–203 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.02.318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guimond S.E., Mycroft-West C.J., Gandhi N.S.et al. (2020) Pixatimod (PG545), a clinical-stage heparan sulfate mimetic, is a potent inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. bioRxiv 10.1101/2020.06.24.169334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in the review.