Abstract

Background. Too frequently, patients with chronic illnesses are surprised by disease-related changes and are unprepared to make decisions based on their values. Many patients are not activated and do not see a role for themselves in decision making, which is a key barrier to shared decision making and patient-centered care. Patient decision aids can educate and activate patients at the time of key decisions, and yet, for patients diagnosed with chronic illness, it would be advantageous to activate patients in advance of critical decisions. In this article, we describe and formalize the concept of the Patient Roadmap, a novel approach for promoting patient-centered care that aims to activate patients earlier in the care trajectory and provide them with anticipatory guidance. Methods. We first identify the gap that the Patient Roadmap fills, and describe theory underlying its approach. Then we describe what information a Patient Roadmap might include. Examples are provided, as well as a review comparing the Patient Roadmap concept to existing tools that aim to promote patient-centered care (e.g., patient decision aids). Results and Conclusions. New approaches for promoting patient-centered care are needed. This article provides an introduction and overview of the Patient Roadmap concept for promoting patient-centered care in the context of chronic illness.

Highlights.

Too frequently, patients with chronic illnesses are surprised by disease-related changes and are unprepared to make decisions based on their values.

In this article, we formalize the concept of a Patient Roadmap tool to provide anticipatory guidance and promote patient-centered care for patients with chronic illnesses.

The Patient Roadmap aims to activate patients early in the care trajectory to prepare them to take part in future decisions.

The Patient Roadmap provides a unique opportunity to introduce patients to likely future decisions, as well as the idea that those decisions may depend on their unique values and preferences.

Keywords: chronic illness, decision aids, patient decision support, patient-centered care, patient roadmap

Introduction

For patients and their family caregivers, the diagnosis of a chronic illness often raises questions and a desire for information that are insufficiently addressed. Living with a chronic illness usually involves multiple choices about treatment options, procedures, and adjustments to functional, social, or quality of life changes. Too frequently, patients are surprised by disease-related changes and are unprepared to make decisions based on their values. Here, we introduce a new paradigm—a Patient Roadmap—to provide anticipatory guidance with the goal of promoting patient-centered care for patients with chronic illnesses. 1

Patients diagnosed with chronic illnesses often face a lifetime of treatment decisions. For the metaphor of the roadmap, at the time of a diagnosis consider being asked to take a cross-country road trip. There are countless roads that can be chosen (treatment options) and the routes can vary in numerous ways. Importantly, the route chosen can be based on personal preferences, values, decision making with travel companions (e.g., doctors, family, and/or caregivers), as well as considering how the route chosen might affect loved ones who are along for the ride. Along the journey there are health situations patients can prepare for, and decisions that can be anticipated like choosing between treatment options. There are also parts of the journey that are less predictable, like weather and road closures, and knowing that these are possibilities can help patients to prepare.

The metaphor of a roadmap creates a framework for engaging patients in values-based considerations about what to expect and what could occur over the illness trajectory as a type of anticipatory patient-centered guidance. While the concept of a roadmap to help guide patients has been in existence for some time,1,2 in this article we formalize the concept of a Patient Roadmap, including distinguishing it from traditional patient education, decision aids for discrete decisions, and advance care planning.

What Gap Does a Patient Roadmap Fill?

A basic tenet of patient-centered care is that health care should be collaborative with patients and family members, involving shared decision making to develop a customized care plan that aligns with patients’ goals.3,4 However, achieving these ideals is challenging. 5 Too often, patients with chronic illnesses are unprepared to take part in decisions when disease-related changes occur. Many patients do not see a role for themselves in health care decisions; that is, they are not activated (connecting to the metaphor, they are the passenger rather than the driver).6,7 Low patient activation has been identified as a key barrier to successful shared decision making.7,8 Patient decision aids (DAs) are a common tool that educates patients and activates them at the time of key decisions.9–11 Yet, for patients diagnosed with chronic illness, it would be advantageous to help patients to see themselves as the driver in advance of critical decisions, such that they feel informed and empowered to participate in their medical care from the beginning of their illness. Hence, the key gap that the Patient Roadmap seeks to fill is to educate and activate patients earlier in the care trajectory (i.e., before patients face a discrete medical decision), in order to prepare them to take part in future decisions.

How Does a Patient Roadmap Uniquely Educate and Activate Patients?

The Patient Roadmap concept draws on the psychological notion of mental models to guide its approach. For the sake of this article, we adopt the definition of mental models as an interrelated set of beliefs that shape a person’s understanding of how something works.12–14 A key feature of mental models is that they guide expectations for the future. In order to be active participants in their care, patients must have reasonably accurate expectations for the future. When a person is diagnosed with a chronic illness they usually receive information about the diagnosis and immediate treatment, but what is often missing is a broader picture of one’s health trajectory, and this trajectory can be especially unclear for patients with lower education or health literacy levels. 15 A Patient Roadmap can improve the accuracy of patients’ expectations by addressing limited awareness or misunderstanding in patients’ mental models of their illness and its likely course.

A Patient Roadmap extends traditional patient education by helping patients understand both their diagnosis and common illness trajectories to give patients a map of what lies ahead. In so doing, the Patient Roadmap provides a unique opportunity to introduce patients to likely future decisions, as well as the idea that those decisions may depend on their unique values and preferences. While some patients have highly unique circumstances that make their trajectory difficult to predict, oftentimes there are disease trajectories that can be anticipated, and communicating these possible paths and addressing common misconceptions can help patients form more accurate expectations, as well as help them understand how the choices that they make now might determine their future options.

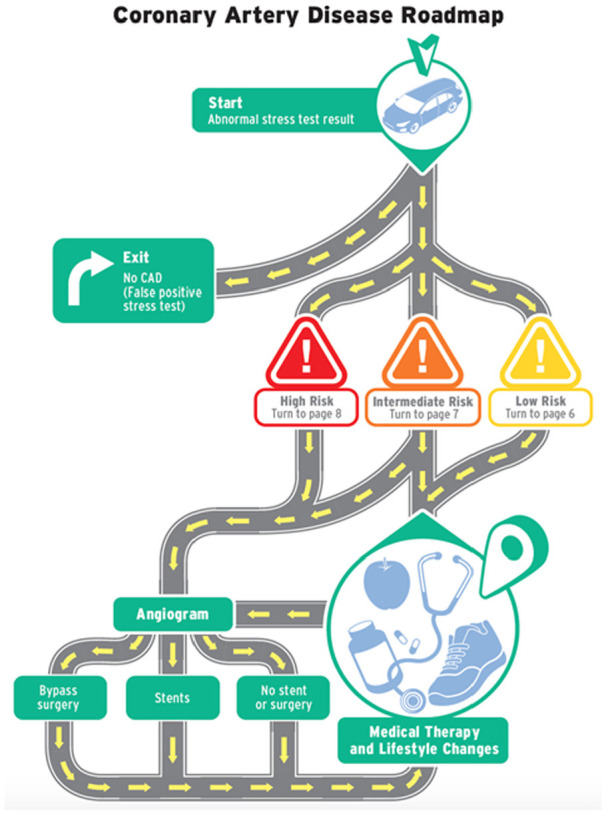

Conveying common illness trajectories and providing anticipatory guidance could include a literal map or visual pathways. For example, Figure 1 displays one page from a multi-page Patient Roadmap tool that is currently being developed by our team for patients newly diagnosed with coronary artery disease (CAD). This figure summarizes different paths that are in front of the patient at the time of an abnormal cardiac stress test and diagnosis of CAD. Many patients with CAD do not understand that CAD is a lifelong illness that is primarily managed with medications, so one critical aspect of this figure is that it shows that all paths lead to the same endpoint, which is medical management of CAD (and lifestyle changes). Other pages of the tool (not pictured) elaborate on this figure, identifying future decisions that depend on patients’ preferences (e.g., getting a coronary stent) and promoting patient engagement in these decisions.

Figure 1.

Example from a coronary artery disease Patient Roadmap tool. In this tool, anticipatory guidance is conveyed using a literal map. This represents a central figure from a multi-page tool, in which other pages expand on each section of the map.

However, a Patient Roadmap does not necessarily have to include a literal map in order to provide anticipatory guidance. In another tool we recently developed for patients with heart failure, no map was provided and instead the heart failure trajectory and future possible treatments were described verbally and with pictures. While a Patient Roadmap cannot include all potential illness trajectories or decisions, the goal is to provide anticipatory guidance and help patients develop more accurate expectations for the future.

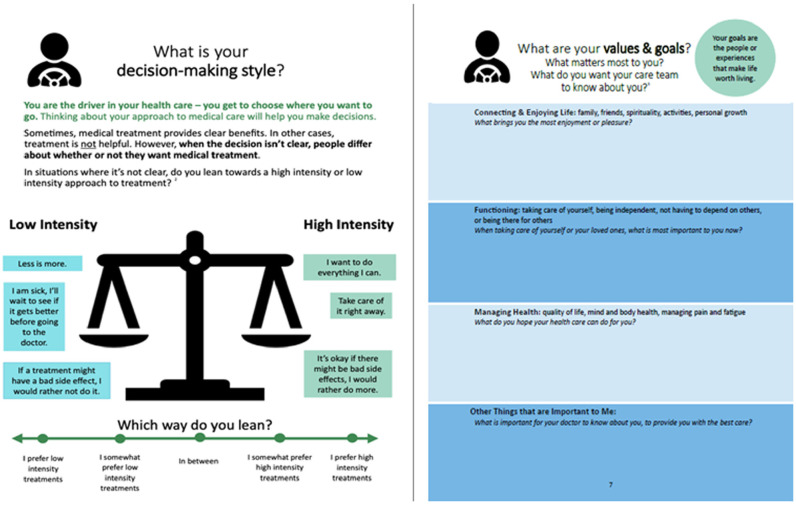

Critically, the roadmap metaphor implies that the patient is the driver and their values matter. Hence, a Patient Roadmap tool should aim to promote values clarification. However, the goal of values clarification in the context of a Patient Roadmap cannot be to clarify values for a discrete decision, and instead should help patients identify their general preferred approach to their health care as a way of guiding them over the long term and over multiple decisions. An important distinction in many disease management contexts is whether treatments are more versus less intensive and burdensome. Medical maximizing-minimizing theory posits that many people have stable and generalized preferences for more versus less intensive approaches to medicine.16–18 Figure 2 displays the values clarification portion of the heart failure Patient Roadmap which was guided by this theory (the CAD Patient Roadmap includes a similar page, not pictured). The heart failure roadmap additionally provides values clarification by eliciting patients’ physical, social, and emotional goals (Figure 2, right panel).

Figure 2.

Example of how values clarification could be accomplished in a Patient Roadmap tool. This figure displays pages from the heart failure Patient Roadmap. Values clarification using medical maximizing-minimizing theory is displayed in the left panel, and values clarification focusing on goals is displayed in the right panel.

What Information Should a Patient Roadmap Provide?

As we currently conceptualize it, a Patient Roadmap should have the following components (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of a Patient Roadmap

| What the Roadmap Does | Connecting to the Roadmap Metaphor |

|---|---|

| Discuss the diagnosis and disease trajectory | Understanding the journey, choosing the route |

| Describes different possible paths of the illness trajectory that can be chosen, as well as illness changes and health events that are not under a person’s control | The patient’s experience can vary by paths purposefully chosen and by uncontrollable events, for example, weather, road closures |

| Describe different treatment options; help patients to anticipate future decisions and point to decisions that the patient can make | The patient is on a journey; the choice of route depends on what the patient wants |

| Clarify patients’ values and goals | The patient is the driver, and their route depends on their broader values and goals |

| Connect the patient with resources; discuss possible need for compromise between values and resources | Identify where to stop, rest, fuel up, and people who can help you along the way; how the journey might be affected by amount of gas in the tank, or the car you’re driving |

| Respond to patients’ emotions | Acknowledging that journeys can be arduous and there are high and low points |

Discuss the Diagnosis

As in traditional patient education, information about the diagnosis should be included, such as what it is, relevant symptoms, and near-term management. This may also involve correcting common misconceptions. Clear communication and accessible language to “name” the condition is especially important in non-oncologic, chronic conditions. Naming and explaining even well after the initial diagnosis could be beneficial if patients feel they need more information or were not well informed at the outset. 19

Introduce Different Disease Trajectories

Information about common trajectories may include what the patient can anticipate for their future health needs, such as lifestyle changes, treatment options, and changes in functional status and caregiver needs. The goal is to introduce the most common disease trajectories, explicitly recognize uncertainty, and provide an opportunity for ongoing discussion.

Anticipate Future Decisions

Decisions about treatment options tend to occur at key forks in the metaphorical “road.” A Patient Roadmap may include information about when future treatment decisions might happen in the context of common disease trajectories. The goal is to help patients become aware of and prepare for future decisions (rather than learning about treatment options at the time of an acute health change). However, as outlined below, it is important not to overload patients with detailed information about these treatments (e.g., numeric risks and benefits); decision-specific DAs can be used when such decisions arise.

Clarify Patients’ Values and Goals

Values-clarification can help patients weigh treatment options and make decisions about their health care that are right for them, both at present and in the future.20–22 For example, a roadmap may discuss treatment options based on patient preferences for more aggressive versus less aggressive disease management, 16 or may provide opportunities for patients to reflect on their goals for how they hope to live the rest of their life.

Connect Patients With Resources

A Patient Roadmap may provide a unique format for connecting patients with additional resources that may be useful at specific decision points or as they live with the illness. For example, in Figure 2 (right panel), patients are provided with a link to DAs for the treatments that are described. A roadmap may link to DAs for specific treatments; prompt patients to connect with interprofessional health care providers such as social workers, chaplains, or behavioral health providers; or connect with community resources, such as fellow patients/peer support, legal counsel, or financial and long-term care planners.

Respond to Patients’ Emotions

Being diagnosed with a chronic illness frequently produces fear and anxiety, and a key challenge to discussing future trajectories is managing and responding to emotions that this information may evoke. Roadmaps should therefore display empathy and acknowledge emotions. In this way, roadmaps are poised to address both the cognitive and emotional aspects of living with an illness.

Additional Considerations

In addition to the content described above, a Patient Roadmap is uniquely suited to address health inequities by meeting the informational needs and concerns of those who are less familiar or comfortable with the health care system. Many disparities in health outcomes are linked to low patient education and knowledge, and poor patient-physician communication.23–27 Educating patients’ broader mental model of their illness and what to expect could be particularly helpful for patients who have had infrequent prior contact with the health care system, and who likely have a less detailed understanding of how the health care system works or what kinds of questions are appropriate to ask. A Patient Roadmap delivered at the time of diagnosis could potentially prepare such patients for more productive conversations with their clinician, provided that it is written at appropriate literacy level and is designed to meet the informational needs of the targeted patient population. At the same time, a Patient Roadmap should be careful to consider the possibility that resources affecting the health care trajectory may be available to some patients and not others.

It is also worth briefly describing what a roadmap is not. A Patient Roadmap cannot convey the exact outcome of the chosen path, or tell the patient how they will feel about that outcome. Each patient is unique and the future is uncertain. Connecting to the metaphor, roadmaps do not predict weather, accidents, or road construction on a chosen path. Moreover, Patient Roadmaps should seek to enhance, not replace, conversations with trusted clinicians who can help put the roadmap information into context; for example, talking through different trajectories given the patients’ unique circumstances and relevant comorbidities. Finally, a Patient Roadmap may be an inappropriate tool in disease contexts where the illness has a highly unpredictable course.

How Does a Patient Roadmap Compare to Existing Tools?

A Patient Roadmap is a type of patient education. However, traditional educational materials do not always serve the purpose of promoting patient-centered, preference-informed care. Next, we compare the Patient Roadmap to two other existing approaches to promote patient-centered care: Decision Aids and Advance Care Planning.

Comparing Patient Roadmaps to Decision Aids

Patient Roadmaps and patient DAs have some similarities and some important differences (Table 2). Researchers, clinicians, and other stakeholders have worked since 2003 to establish an evidence-informed framework for the development and evaluation of DAs. These standards, referred to as the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS), form a guideline for development of DAs.28,29 The IPDAS guidelines are important in providing clarity regarding what a DA actually is to prevent groups with perverse incentives from developing thinly veiled advertisements and referring to them as DAs.

Table 2.

What Elements Should a Roadmap Include? Comparing Roadmaps to Decision Aids (DAs) Using the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Instrument (IPDASi)

| IPDASi Criteria | Included in a Roadmap? | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information about options | Describes health condition or problem | Yes | Important feature of a roadmap |

| Describes a decision | Yes, qualified | A Roadmap can highlight decisions to come, and can direct users to DAs that provide more detail | |

| Describes options available | Yes, qualified | A Roadmap might describe general treatment options, for example, medications that might be prescribed, but should avoid providing too much detail (see below) | |

| Describes natural course of health condition or problem | Yes | Important feature of a roadmap; this is something that roadmaps should do well | |

| Describes positive and negative features of each option | No | Roadmaps can highlight decisions to come, but will generally not provide detailed information about specific decisions (a task better suited to a DA) | |

| Makes it possible to compare features | No | ||

| Shows negative and positive features with equal detail | No | ||

| Probabilities of outcomes | Provides information about outcome probabilities; specifies groups for whom outcome applies, rates of outcomes, time periods, and presents probabilities in multiple formats | No | Roadmaps should avoid providing details such as probabilities. Detailed information about specific options, such as probabilities, is unlikely to be read by a patient who has not reached that point in the road. Roadmaps can refer patients to DAs when available and appropriate. |

| Values | Helps patients imagine what it is like to experience physical, psychological, and social effects of options | Yes, qualified | Rather than effects of specific options, a Roadmap could help patients imagine what it is like to experience the disease at different points in time and given different treatment paths |

| Asks patients to think about what matters most to them | Yes, qualified | A Roadmap should provide values clarification, but should be related to broad goals and preferences rather than preferences for discrete treatment options | |

| Decision guidance | Provides step-by-step way to make a decision | No | A Roadmap does not address a specific decision |

| Includes worksheets or questions to use when talking with provider | Yes, qualified | Could help patients articulate their goals and values related to their care trajectory | |

| Development | Finding out what patients need | Yes | Patients should be involved in the development process, to identify what information they need and how to organize and present it optimally |

| Finding out what health professionals need | Yes | Health professionals should be involved to identify key areas of communication difficulty, such as managing patient expectations | |

| Expert review by patients and health professionals not involved in developing the tool | Yes | Important aspect of Roadmap development | |

| Field tested | Yes | Important aspect of Roadmap development | |

| Plain language | Reports readability levels | Yes | Important aspect of Roadmap development and readability should be at 7th grade or below |

| Decision support tool evaluation | There is evidence that the tool helps patients improve their knowledge | Yes | Roadmaps should improve knowledge about disease and accurate expectations for the future |

| There is evidence that the tool improves the match between the features that matter most to the patient and the option chosen | Yes, qualified | In a Roadmap, the “option chosen” may be reconceptualized as the path taken, for example, an aggressive, life-sustaining path versus a less intensive treatment path |

DAs differ from our conceptualization of a Patient Roadmap most notably in that the former are designed for discrete decisions, and according to IPDAS criteria, must provide sufficient detail to support decision making for that decision. This information often includes presenting options and the probabilities of outcomes with considerable detail. In contrast, Patient Roadmaps may refer to multiple future decisions with less detail. Complicated numerical information pertaining to specific decisions in the distant future, some of which may not ever come to pass, will likely not be relevant to patients until they are directly facing that decision. Therefore, while Patient Roadmaps might refer to future decisions, they would provide an overview of those decisions and refer patients to specific DAs when a particular decision becomes relevant.

An important similarity between Roadmaps and DAs is that they both aim to enhance patient-centeredness of care.3,30 Most critically, they both aim to activate patients and assure that the patient’s goals and values guide the care that a person receives. 20 Thus, both Patient Roadmaps and DAs should include methods for helping patients clarify and express their values and then provide guidance in communication to assure that chosen treatments and any associated changes in trajectories are consistent with those values. Values clarification for Roadmaps are likely to be generalized, broad, and sensitive to changes based on the disease trajectory whereas values clarification for DAs are often anchored to specific risks, benefits, burdens or other aspects of a single decision.

Comparing Patient Roadmaps to Advance Care Planning

In the context of end-of-life decision making, it might be easy to confuse a Patient Roadmap with Advance Care Planning (ACP). One consensus definition of ACP is “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care.” 31 This definition reflects the shift in focus from documentation of end-of-life preferences in medical-legal advance directives to the need for ongoing, individualized preparation for communication and in-the-moment decision making when a person lacks decision-making capacity.32,33 ACP often focuses on the choice of surrogate medical decision makers, values clarification that can be applied to future medical decisions, and documentation of advance directives that pre-specify medical treatments that patients want or will not want when they are dying. 34 However, a limitation of current ACP is that the process may be completed without shared decision making related to the patient’s illness trajectory, a broader range of treatment options and decisions that may occur over time, and expected prognosis.

Designed to be longitudinal and disease-specific, a Patient Roadmap equips a patient for shared decision making by describing a common illness trajectory, potential treatment decisions, and introducing decisions that a patient may encounter. Patient Roadmaps may have intermediate (e.g., chronic medication management for coronary artery disease, need for long-term caregiver support for dementia) and long-term endpoints (e.g., mortality) that all patients will encounter to facilitate ongoing discussions and planning for medical decisions. Unlike advanced directives that apply to future unknown medical situations, Roadmaps are tools that may help patients consider how their personal values can inform current or near-future decisions, as well as longer term or end-of-life decisions. Depending on the patient’s decisions, specific conversations using a Patient Roadmap could lead to documentation of life-sustaining treatment orders. 35

Clinical Examples: Heart Failure and Dementia

In this section, we take two diseases—heart failure and dementia—and briefly describe how a Patient Roadmap might address the unique challenges and informational needs therein.

Heart Failure

We used a heart failure Patient Roadmap in earlier examples, and here we briefly describe the rationale for a Patient Roadmap in this health context. The informational needs of patients with heart failure are often underaddressed. For example, in one survey of heart failure patients, 18% of patients had no understanding of what heart failure meant, even months after they had been diagnosed, and a large majority (73%) wanted more information about their diagnosis. 19 Perhaps because of lack of information about their health trajectory, patients frequently overestimate their survival, 36 those dying from heart failure engage hospice at half the rate of their counterparts with cancer and patients with end-stage heart failure have worse quality of life than patients with metastatic cancer. 37

A Patient Roadmap like the one described earlier conveys information about the diagnosis and disease trajectory, allowing patients to better understand their current health and anticipate future changes and decisions. It communicates the purpose of different medications and why those medications are important for extending life and managing symptoms, reinforcing the information patients also receive from their doctor and potentially fostering greater adherence. It introduces patients to the possibility of more extensive treatments as their heart failure worsens, such as choosing an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) or left ventricular assist device (LVAD), thus preparing them to be involved in those decisions. It could also begin discussions about end-of-life care, and help patients consider how they desire to live the rest of their life and what kind of care (e.g., more or less intensive) they choose.

Dementia

A diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias, including Parkinson’s disease dementia, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and others, is often devastating for the person receiving the diagnosis and their care partners. Because the onset of symptoms can be insidious or discussion of the diagnosis may be distressing, there is often underdiscussion of the diagnosis, education about living with dementia, and information about long-term disease trajectories. As a result, many persons with dementia and their family care partners are unprepared for common dementia-related changes and associated treatment and care decisions. High-quality dementia care includes identifying and supporting patients’ and families’ preferences and quality of life, often over several years and multiple decisions as the patient’s cognitive and functional abilities decline.

A Patient Roadmap could serve as a tool to support persons living with dementia and their family care partners. At the time of diagnosis, and throughout the illness trajectory, patients and care partners often desire information related to the stage of the illness, and whether medications or other treatments can alter the trajectory. The roadmap can emphasize the importance of care partner education and support. The roadmap can introduce and provide anticipatory guidance related to expected changes to financial, social, safety, and functional abilities as dementia progresses and the person loses decision-making capacity. 1 As a tool, the roadmap can focus discussions on current areas of need on the roadmap (i.e., increasing care partner support), while also opening up ongoing discussions of patient and care partners’ values and resources related to future decisions (i.e., nursing home care or end-of-life care).

What Is an Ideal Development Process for Patient Roadmaps?

As with high-quality patient education materials and patient DAs, Patient Roadmaps should be developed to include relevant, unbiased, and evidence-based information. We propose that the development process for Patient Roadmaps follow similar steps as proposed by the IPDAS criteria for patient DAs and listed in Table 2. These steps included identifying what information patients need from the perspective of patient and clinician stakeholders, expert review by patients and health professionals who were not involved in developing the tool, and field testing to establish that the tool increases key patient-centered outcomes (e.g., knowledge, patient activation, shared decision making, etc.).

Assessments of the quality of Patient Roadmaps should also include a number of process domains related to how the tool was developed and maintained.11,28,38 These domains should include 1) transparency about the process, including the types of stakeholders involved at each stage of development and what forms of feedback were solicited and from whom; 2) ensuring the tool is comprehensive and spans decisions patients are likely to face across the disease trajectory; 3) availability of any data from field testing such as how the tool functions in underrepresented groups, in patients at different ages or with differing clinical characteristics; and 4) availability of the tool within the public domain, optimally through modalities that overcome the digital divide. With this information available, individual clinicians, practices, health systems, payers, and other stakeholders can meaningfully assess the quality of a Patient Roadmap for use with their patients. Patient Roadmaps should also conform to guidance for writing effective health education materials. 39

Moreover, a key component to consider in the development and evaluation of a Patient Roadmap is its use in clinical practice. There should be a focus on designing for dissemination and implementation that considers the perspectives of multiple stakeholders to facilitate successful adoption by patients, families, and clinicians.40,41 Needs assessments should be undertaken, including an assessment of what and how much patients need and want to know, and when in the illness trajectory they are most receptive to that information (e.g., at the time of diagnosis, versus later on). If a Patient Roadmap is too broad or vague, or it provides information that patients do not need or already know, then it is unlikely to be used or improve patient-centered care.

Care should also be taken to identify at what stage in the disease process a Patient Roadmap is designed to be delivered, and how it would be optimally delivered (e.g., email, mail, in the clinical encounter, etc.), in order to be most useful to both patients and clinicians. Ideally, a roadmap would be designed to be used iteratively during the course of the illness, and be able to be viewed by patients and families independently, without a clinician present. The potential for iterative use of the roadmap should be considered, including how the tool might be designed to be useful for patients at multiple disease stages.

The use of a Patient Roadmap is not a substitute for a clinical discussion between patients and clinicians but is a complementary tool to guide patients and care partners through their chronic illness journey and foster collaboration with clinicians and other resources. Moreover, the Patient Roadmap concept and associated development process could serve as a guide for knowledge translation, for example, translating complex knowledge about the processes of care for cancer patients into a format that is maximizes the potential for patient activation and patient-centered care. 42

Conclusions

This article describes the concept of a Patient Roadmap for chronic illnesses. Too often, patients with serious or chronic illnesses do not anticipate future disease-related changes and decisions, and do not perceive that they can have an active role in these decisions. These are critical barriers to shared decision making and achieving patient-centered care. The key gap that the Patient Roadmap seeks to fill is to educate and activate patients, similar to a decision aid but earlier in the care trajectory, thus preparing them to take part in future decisions. To do this, the Patient Roadmap guides patients’ expectations for the future and, in so doing, provides an opportunity to introduce likely future decisions and how they can participate in those decisions. The concept of a Patient Roadmaps will likely evolve, and therefore we view this document not as a final prescription but rather as a conceptual beginning. We hope that the Patient Roadmap proves to be a useful concept, and further advances the goal of patient centered care across multiple health domains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Angela Fagerlin for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support for this study was provided to authors Matlock and Allen by NIH/NHLBI, PCORI, and to Scherer by NIH/NCI. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in writing and publishing the report.

ORCID iDs: Laura D. Scherer  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8660-7115

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8660-7115

Daniel D. Matlock  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9597-9642

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9597-9642

Chris E. Knoepke  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3521-7157

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3521-7157

Contributor Information

Laura D. Scherer, Division of Cardiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado; Adult and Child Consortium for Health Outcomes Research and Delivery Science, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado; VA Eastern Colorado, Aurora, Colorado.

Daniel D. Matlock, Adult and Child Consortium for Health Outcomes Research and Delivery Science, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado; VA Eastern Colorado, Aurora, Colorado.

Larry A. Allen, Division of Cardiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado

Chris E. Knoepke, Division of Cardiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado

Colleen K. McIlvennan, Division of Cardiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado

Monica D. Fitzgerald, Adult and Child Consortium for Health Outcomes Research and Delivery Science, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado

Vinay Kini, Division of Cardiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado.

Channing E. Tate, Adult and Child Consortium for Health Outcomes Research and Delivery Science, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado

Grace Lin, Department of General Internal Medicine, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California.

Hillary D. Lum, Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado VA Eastern Colorado, Aurora, Colorado.

References

- 1. Jordan SR, Kluger B, Ayele R, et al. Optimizing future planning in Parkinson disease: suggestions for a comprehensive roadmap from patients and care partners. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(suppl 1):S63–S74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lum H, Montgomery E. New web resource available to help Coloradans with future medical planning [cited March 1, 2021]. Available from: http://epubs.democratprinting.com/article/New+Web+Resource+Available+To+Help+Coloradans+With+Future+Medical+Planning/3284774/561981/article.html

- 3. Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—the pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. NEJM Catalyst. What is patient-centered care [cited May 8, 2020]? Available from: https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/CAT.17.0559

- 5. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 pt 1):1005–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):520–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith SG, Pandit A, Rush SR, Wolf MS, Simon CJ. The role of patient activation in preferences for shared decision making: results from a national survey of US adults. J Health Commun. 2016;21(1):67–75. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1033115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, et al. Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic review. BMJ. 1999;319(7212):731–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elwyn G, Burstin H, Barry MJ, et al. A proposal for the development of national certification standards for patient decision aids in the US. Health Policy. 2018;122(7):703–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson-Laird PN. Mental models of meaning. Philip N. Johnson-Laird. In Joshi A., Weber Bruce H., Sag Ivan A. (eds.), Elements of Discourse Understanding. Cambridge University Press. pp. 106–126; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fiske ST, Linville PW. What does the schema concept buy us? Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1980;6(4):543–57. doi: 10.1177/014616728064006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson-Laird PN. Mental models and deduction. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5(10):434–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scherer LD, Caverly TJ, Burke J, et al. Development of the Medical Maximizer-Minimizer Scale. Health Psychol. 2016;35(11):1276–87. doi: 10.1037/hea0000417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scherer LD, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Eliciting Medical Maximizing-Minimizing preferences with a single question: development and validation of the MM1. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(4):545–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Groopman J, Hartzband P. Your Medical Mind: How to Decide What Is Right for You. Penguin Publishing Group; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Banerjee P, Gill L, Muir V, et al. Do heart failure patients understand their diagnosis or want to know their prognosis? Heart failure from a patient’s perspective. Clin Med (Lond). 2010;10(4):339–43. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.10-4-339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Llewellyn-Thomas HA. Values clarification. In Shared Decision-Making in Health Care: Achieving Evidence-Based Patient Choice. Oxford University Press; 2009:123. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fagerlin A, Pignone M, Abhyankar P, et al. Clarifying values: an updated review. BMC Med Inform Decis Making. 2013;13(suppl 2):S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Witteman HO, Gavaruzzi T, Scherer LD, et al. Effects of Design Features of Explicit Values Clarification Methods: A Systematic Review. Medical Decision Making. 2016; 36: 760–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Braveman P. Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wicher CP, Meeker MA. What influences African American end-of-life preferences? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(1):28–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Paget L, Han P, Nedza S, et al. Patient-Clinician Communication: Basic Principles and Expectations. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marmot M; Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet. 2007;370(9593):1153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Daniel H, Bornstein SS, Kane GC; Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Addressing social determinants to improve patient care and promote health equity: an American College of Physicians Position Paper. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(8):577–8. doi: 10.7326/M17-2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration. IPDAS 2005: criteria for judging the quality of patient decision aids [cited February 17, 2015]. Available from: http://www.ipdas.ohri.ca/ipdas_checklist.pdf

- 29. Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333(7565):417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shafir A, Rosenthal J. Shared decision making: advancing patient-centered care thought state and federal implementation [cited May 14, 2021]. Available from: https://www.nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/default/files/shared.decision.making.report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821–32.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heyland DK. Advance care planning (ACP) vs advance serious illness preparations and planning (ASIPP). Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(3):218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morrison RS. Advance directives/care planning: clear, simple, and wrong. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(1):14–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. POLST: Portable medical orders for seriously ill or frail individuals [cited November 24, 2020]. Available from: https://polst.org/

- 36. Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(15):1928–52. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824f2173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cross SH, Warraich HJ. Changes in the place of death in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(24):2369–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Knoepke CE, Allen LA, Kramer DB, Matlock DD. Medicare mandates for shared decision making in cardiovascular device placement. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(7):e004899. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.004899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hoffmann T, Worrall L. Designing effective written health education materials: considerations for health professionals. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(19):1166–73. doi: 10.1080/09638280410001724816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Owen N, Goode A, Sugiyama T, et al. Designing for dissemination in chronic disease prevention and management. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2017:107–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brownson RC, Jacobs JA, Tabak RG, Hoehner CM, Stamatakis KA. Designing for dissemination among public health researchers: findings from a national survey in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1693–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jones PH, Shakdher S, Singh P. Synthesis maps: visual knowledge translation for the CanIMPACT clinical system and patient cancer journeys. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(2):129–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]