Abstract

Boronic acids are known reversible covalent inhibitors of serine β-lactamases. The selectivity and high potency of specific boronates bearing an amide side chain that mimics the β- lactam’s amide side chain have been advanced in several studies. Herein, we describe a new class of boronic acids in which the amide group is replaced by a bioisostere triazole. The boronic acids were obtained in a two-step synthesis that relies on the solid and versatile copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) followed by boronate deprotection. All of the compounds show very good inhibition of the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase KPC-2, with Ki values ranging from 1 nM to 1 μM, and most of them are able to restore cefepime activity against K. pneumoniae harboring blaKPC-2. In particular, compound 1e, bearing a sulfonamide substituted by a thiophene ring, proved to be an excellent KPC-2 inhibitor (Ki=30 nM); it restored cefepime susceptibility in KPC-Kpn cells (MIC=0.5 μg/ mL) with values similar to that of vaborbactam (Ki=20 nM, MIC in KPC-Kpn 0.5 μg/mL). Our findings suggest that α-triazolylboronates might represent an effective scaffold for the treatment of KPC-mediated infections.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, beta-lactamase inhibitors, boronic acids, click chemistry, Klebsiellae pneumoniae

Introduction

In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae has disseminated to all regions of the world. This unwelcome observation is associated with the development of serious infections and an increase in morbidity and mortality.[1] Navon-Venetia et al. reported that this organism is responsible for one-third of all Gram-negative infections such as urinary tract infections, cystitis, pneumonia, surgical wound infections, endocarditis and septicemia.[2] A meta-analysis published in 2020 confirmed that the trend in the isolation rate of K. pneumoniae is increasing and there is a rapid global emergence of strains of this organism resistant to almost all antibiotics, including carbapenems.[3] The main resistance mechanism responsible for antibiotic resistance is the production of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs), β- lactamases belonging to class A. β-lactamases form an acylenzyme adduct with the antibiotic, which is then easily hydrolyzed by a water molecule; thereby, the drug is made ineffective (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Mechanism of action of serine β-lactamases.

To date, at least 54 variants of KPC have been identified, although KPC-2 and KPC-3 are the most common.[4] Usually, K. pneumoniae strains are resistant to penicillin and cephalosporin as well and they are poorly inhibited by classical β -lactamase inhibitors, such as clavulanate, tazobactam, and sulbactam.[5]

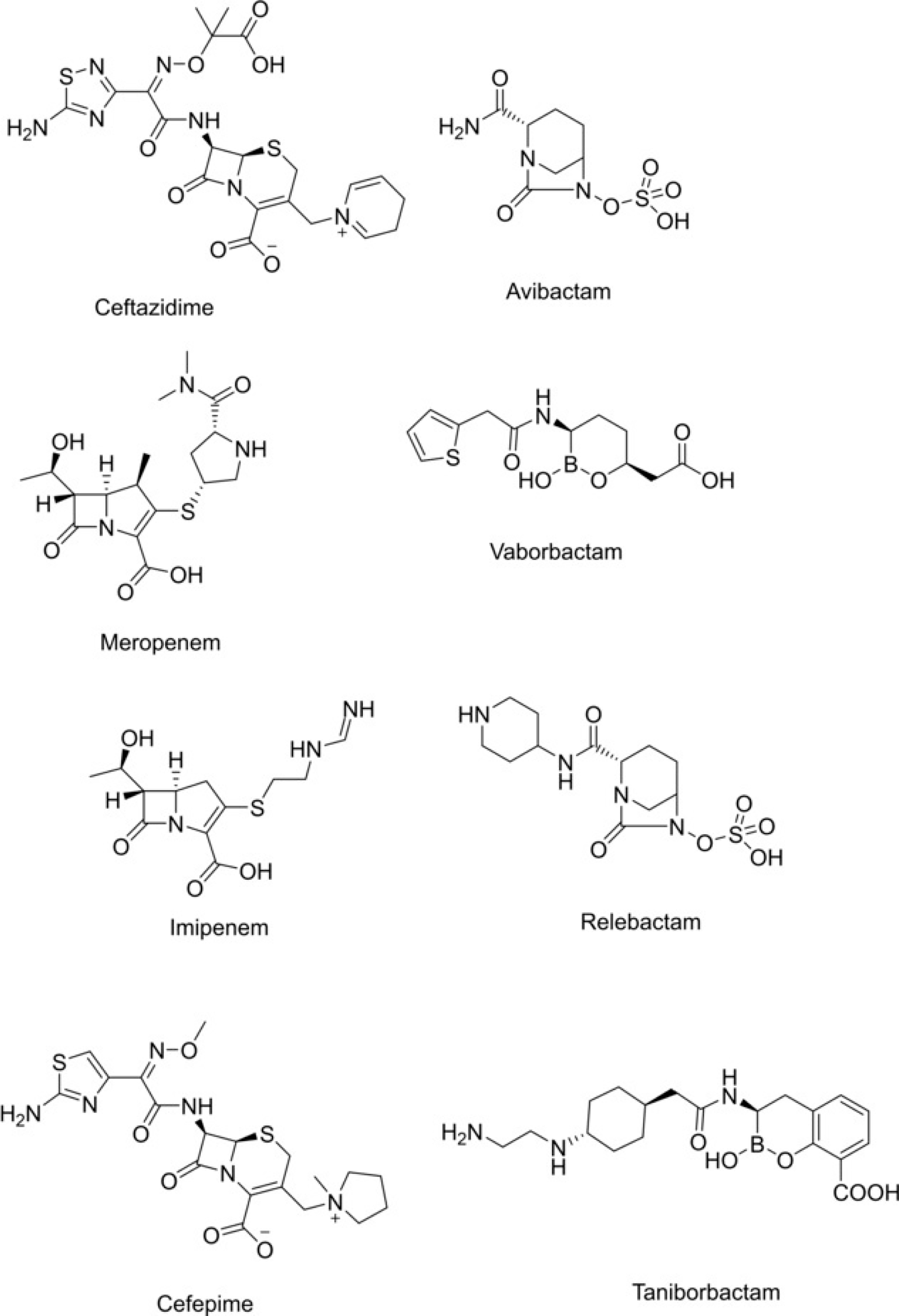

Therefore, treatment options against resistant K. pneumoniae are limited. β-Lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, such as ceftazidime-avibactam, meropenem-vaborbactam and the recently approved (July 2019) imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam are hoped to provide an answer to this crisis (Figure 1).[6,7]

Figure 1.

Approved treatments against K. pneumoniae.

Other β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, for example, cefepime-taniborbactam are in clinical or preclinical development[7] Avibactam is the first diazabicyclooctane (DBO) β-lactamase inhibitor that has reached the clinic. The DBO inhibits class A, C and some class D β-lactamases.[8–10]

Unfortunately, many cases of resistance are reported. Resistance often emerges due to mutation in the KPC Ω-loop (Figure 2). In the KPC-2 serine β-lactamases, most of the active-site residues are conserved, and are preserving their conformation. Catalytic serine S70:NH forms the oxyanion hole with T237: NH and, with the help from a water molecule, facilitate the acylation of β-lactams. The deacylation is facilitated by a water molecule as well, and E166, or K73, S130 residues. Most of the interactions of KPC-2 with the antibiotics are with N132, S130, K234, T235 and R220. The flexibility of W105 side chain was captured in several crystal structures (Figure 2) in the apo-enzyme (PDB ID: 2OV5), and KPC-2-avibactam (PDB ID: 4ZBE) structures W105 (magenta) to the catalytic S70, and is flipping more than 90° (green) when vaborbactam is bound (PDB ID: 6TD0). The large flexibility of the W105, is changing the geometry and the volume of the active site. Along with the mutations in the Ω-loop, this change results in enhanced antibiotic binding and reduced inhibitor (avibactam) binding.[11–13]

Figure 2.

KPC-2 serine β-lactamases active site with important catalytic residue labeled and Ω-loop colored yellow. The side chain of W105 is very flexible; in the apo-enzyme (PDB ID: 2OV5) and KPC-2-avibactam (PDB ID: 4ZBE) structures, W105 (magenta) is close to the catalytic S70; it flips more than 90° (green) when vaborbactam is bound (PDB ID: 6TD0).

Vaborbactam (Figure 1) is a β-lactamase inhibitor containing a cyclic boronic acid which was introduced into the market in 2017. Vaborbactam was initially designed to act as an inhibitor of KPC,[14] but it also inactivates other class A and class C β- lactamases and demonstrates some activity against class B metallo-β-lactamase.[7] The inhibitor is combined with meropenem for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant infections, although in vitro resistance was observed due to loss of porins expression or to the increase in the expression of blaKPC.[15–17]

In this work, we present the inhibitory activity of 14 1,2,3- triazol-1-ylmethaneboronic acids against KPC-2 carbapenemase. We demonstrate the extent these inhibitors restore susceptibility against resistant K. pneumoniae strains in combination with cefepime (FEP). The choice of the 1,2,3-α-triazolylboronic acid scaffold was directed at mimicking the α-amidoboronate, which is a well-known common feature of β-lactamase inhibitors, including vaborbactam and taniborbactam. Furthermore, such α-triazolylboronates are easily obtained through copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), a protocol that proceeds under mild conditions, with inexpensive reagents, high efficiency and straightforward product isolation.[18] Besides the easy synthetic access, these boronates exhibit inhibition constants (Ki) values in the nanomolar range and prove able to restore cefepime susceptibility in resistant Klebsiellae strains.[19] Activity of α-triazolylboronic acids is compared to avibactam and vaborbactam.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

1,4-Disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole rings are known as nonclassical Z-trans-amide isosteres, with the two lone pairs of N-2 and N-3 acting as a hydrogen bond acceptor and the C—H bond as a hydrogen bond donor.[20]

The 1,2,3-triazol-1-ylmethaneboronic acids 1 a–n (Figure 3) were obtained in a two-step synthesis (Scheme 2) through CuAAC between (+)-pinanediol α-azidomethaneboronate 2 and terminal alkynes 3 a–n bearing the selected substituents.[21] In particular all alkynes were synthesized starting from propargyl-amine, most of them (3e–n) with simple commercially available sulfonyl chlorides to give the proper sulfonamide. The click products (+)-pinanediol esters were deprotected through transesterification and the corresponding boronic acids 1 a–n were afforded in 60–85% yield.[18,22]

Figure 3.

1,2,3-triazol-1-ylmethaneboronic acids.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 1,2,3-triazol-1-ylmethaneboronic acids.

Inhibition kinetics and antibiotic susceptibility

The binding affinities for each compound 1 a–n with KPC-2 enzyme were determined using competition assays with nitrocefin as substrate and are reported in Table 1. Compounds 1 e–n obtained from substituted methylsulfonamide alkynes, performed in general better (K{ values from 1 to 92 nM) than the planar substituted carboxamides 1 c and 1 d (compounds Ki’1c = 1.28 μM and/Ki1d = 0.196 μM).

Table 1.

Binding affinity constant (Ki) of compounds 1a–n for KPC-2 and MIC values of cefepime (FEP) in combination with 10 μg/mL of compounds 1a–n.

| Compound | Ki [μM][a] | MIC [μg/mL]. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| t = 5 min | KPC-Kpn[b] | K. pneum blaKPC-2 | |

| FEP | 32 | 32 | |

| 1a | 1.03 ± 0.2 | 4 | 4 |

| 1b | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 2 | 4 |

| 1c | 1.28 ± 0.2 | 4 | 2 |

| 1d | 0.196 ± 0.02 | 8 | 16 |

| 1e | 0.030 ± 0.003 | 0.5 | 2 |

| 1f | 0.006 ± 0.0005 | 4 | 4 |

| 1g | 0.001 ± 0.0001 | 4 | 4 |

| 1h | 0.295 ± 0.02 | 8 | 8 |

| 1i | 0.092 ± 0.01 | 1 | 2 |

| 1j | 0.026 ± 0.003 | 2 | 16 |

| 1k | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 4 | 16 |

| 1l | 0.057 ± 0.006 | 16 | 32 |

| 1m | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 8 | 16 |

| 1n | 0.042 ± 0.005 | 1 | 2 |

| avibactam | 0.002 ± 0.0002 | < 0.12 | < 0.12 |

| vaborbactam | 0.02 ± 0.003 | 0.5 | 1 |

Ki corrected for nitrocefin activity (Km = 8 μM).

All compounds (10 μg/mL) were tested in combination with FEP (0.12 to 128) μg/mL

The only exception was compound 1h (K¡ = 0.295 μM), which besides the phenylsulfonamido side chain bears a tetrazole ring on the phenyl para position, thus suggesting that a negative charge in this position is detrimental to affinity. This observation is corroborated by the affinities detected for compound 1m, bearing a methoxycarbonyl substituent (Ki = 10 nM), and compound 1 n, bearing a carboxylate (K¡ = 42 nM).

Both series of compounds bearing a carboxamide and a sulfonamide point to an improvement of enzyme recognition (enhancement of activity) when an aromatic ring is inserted. Comparison of compounds 1c with 1d and 1i with 1j demonstrated a gain in affinity for KPC-2 enzyme by more than 6 times in acylamido compounds (k¡1c = 1.28 μM vs Ki1d = 0.196μM) and by 4 times in sulfonamido compounds (Ki1i = 92 nM vs Ki1j = 26 nM). The activity of compounds 1 a-n in combination with cefepime (MICs) against Klebsiella blaKPC-2 and KPC-Kpn cells were also determined (Table 1). In previous studies, the triazole ring proved to confer rapid penetration into Acinetobacter strains,[23] and this behavior is confirmed for Klebsiella. Cefepime was chosen as partner as it exhibits rapid cell penetration and it is stable to AmpC cephalosporinases. The compounds (with the only exception of 1I) lowered the MIC for cefepime in both strains, with some of them below the susceptible threshold.[19] However, the trend of antimicrobial activities was not always correlated with Ki values. Although the presence of a negative charge was detrimental for affinity, it improved MICs: compound 1 n had MICs of 1 μg/mL in KPC-Kpn strain and 2 μg/mL in Klebsiella blaKPC-2, values three fold higher than the structurally related compound 1 m. Comparison between compounds bearing the cyano group 1 g and the tetrazole ring 1 h confirmed that whereas the negative charge lowered activity by 300 times (Ki1g = 1 nM vs Ki1h = 295 nM), MICs lower onefold. The presence of a phenyl ring on the triazole substituent had opposite effect on MICs in respect to Ki values, given the decrease of MICs from compounds 1c to 1d and from 1i to 1j (Table 1). The compound with the best affinity for KPC-2 is 1 g, with a Ki as low as 1 nM. This compound bears a p-cyanophenyl substituent on the sulfonamide, and it exhibits good microbiological activity (MIC of 4 μg/mL for both strains). However, the compound with the best effect in restoring antibiotic susceptibility associated with β-lactamase inhibition is 1 e (Ki1e = 30 nM, MIC in KPC-Kpn 0.5 μg/mL) with a thiophene replacing the phenyl ring. Many factors must be considered with interpreting MIC and kinetic differences. The complexity of β-lactamase background, cell entry, efflux, time dependence of inhibition, etc. As we further explore these compounds with different β-lactamase inhibitors, these issues will be resolved. The data for compound 1 e is closely comparable with those obtained for the commercially available cyclic boronate vaborbactam (Ki = 20 nM, MIC in KPC-Kpn = 0.5 μg/mL). This is remarkable considering that vaborbactam has two stereocenters and a more complex synthetic access;[14] at the same time, it underlines the potential offered by the triazoleboronates as bioisostere of amidoboronates.

Aiming to rationalize these observations we performed docking studies of the inhibitors-enzyme complexes. The crystal structures of KPC-2 apo-enzyme (PDB ID: 2OV5) and KPC-2 in complex with avibactam (PDB ID: 4ZBE) or vaborbactam (PDB ID: 6TD0) showed that W105 side chain, positioned at the entrance of the active site is changing its position more than 90° (Figure 2). The molecular modeling based on KPC-2 apo- enzyme is consistent with the crystal structures, showing that the flexibility of W105 changes in the active-site cavity, and the receptor-ligand interaction surface (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Molecular modeling of 1g and 1 e into the active site of KPC-2 (PDB ID: 2OV5) with the W105 side chain flipping more than 90° and changing the active-site cavity.

The molecular docking for compounds 1 g and 1 e suggests that the α-triazolylboronic acids are accommodated very well into the active site of the KPC-2 enzyme. In particular the triazole ring is making favorable π- π stacking interaction with W105, thus allowing the best positioning of the boronic group (Figure 5). We caution that docking studies only provide hypothesis to assist in the interpretation of Ki values for such very active compounds, and further crystallographic experiment are needed.

Figure 5.

Molecular modeling of 1g and 1 e into the active site of KPC-2 after minimization of the enzyme-ligand complex. The triazole ring is a driving moiety in binding and stabilizing the compounds into the active site of KPC- 2. Molecular docking suggests that compounds (1 e here) have multiple conformations, with similar energetics (Figures S2–S4 in the Supporting Information). The π - π stacking interactions between W105 and triazole ring help to “guide” the boronates to form productive interactions with catalytic serine.

Conclusion

Resistance against “last resort” carbapenems is growing among K. pneumoniae strains worldwide. Currently, available therapies with last-generation agents such as avibactam or vaborbactam are effective in fighting infections carried by these organisms, but resistance is emerging, and better approaches are needed. In this work we present the 1,2,3-triazol-1-ylmethaneboronic acid as a new promising scaffold for K. pneumoniae carbapene- mases (KPCs) inhibition. Synthesis of these inhibitors is accomplished in two steps and relies on the rapid and efficient click chemistry reaction. Compound 1 e bearing a sulfonamide substituted by a thiophene ring proves to be an excellent KPC-2 inhibitor (Ki 30 nM) and it restores cefepime susceptibility in KPC-Kpn cells; these values are comparable to the commercially available vaborbactam which is prescribed for Klebsiella infections. More experiments are needed to determine the exact binding mode of these molecules and to investigate their cross-class activity. However, these findings suggest the potential offered by the α-triazolylboronates in KPC-mediated resistance.88888

Experimental Section

Chemistry

All compounds were synthesized and characterized according to previously described procedures.[18] The azidomethaneboronate (2 in Scheme 1) reacted with a selected terminal alkyne (3) in a CuAAC reaction to obtain the (+)-pinanediol ester. Then the deprotection by transesterification with isobutylboronic acid allowed to obtain the desired compounds 1a–n in good yield (60–85 %).[22] Synthesis and characterization of compounds 1 a–n and copies of 1H and 13C The NMR spectra of compounds are given in the Supporting Information.

Antibiotic susceptibility

Micro-broth dilution MICs performed as previously described,[22] and according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines[24] Briefly, bacterial cultures, K. pneumoniae expressing blaKPC-2 were grown overnight in Mueller-Hinton (MH) broth. Bacterial liquid culture was then diluted to a McFarland Standard (OD600 0.224). The antibiotic partner cefepime (FEP) was added as serial dilutions, from 128 to 0.12 μg/mL, and the boronic acids were added at a constant 10 μg/mL concentration. The plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight, and the results were recorded the next day.

Purification and kinetics

KPC-2 β-lactamase was expressed as previously described[25] and purified using cation exchange chromatography. The inhibition constants (K¡) for each of the boronic acids with KPC-2 were determined using competition kinetics. Using nitrocefin (NCF) as a substrate of KPC-2, boronic acids 1 a–n and avibactam and vaborbactam were tested as previously described[25–27] The measurements of the initial velocities were performed with the addition of 100 μM NCF after a 5 min pre-incubation of the enzyme (2 nM) with increasing concentration of the inhibitor. The average velocities (v0) were then fitted to equation:

where vu represents the NCF uninhibited velocity and Ki, represents the inhibitor concentration that results in a 50% reduction of vu. The Ki values for all compounds were corrected for the NCF affinity (Km = 8 μM) by using the equation:

Molecular docking

The crystal structure of KPC-2 (PDB ID: 2OV5) was used for the molecular docking. Using BIOVIA, Discovery Studio,[28] molecular modeling software, the KPC-2 structure was minimized to a RMSD of 0.001 Å. The minimization was done using a Conjugate Gradient algorithm, with Generalized Born with a simple Switching model for solvent. The long-range electrostatics were treated with the particle Mesh Edwald method for periodic boundary condition. The active- site cavity was defined from the known active-site residue, with catalytic serine. The boronic acid compounds were built, minimized,and automat docked into the active site of KPC-2 structure using CDOCKER protocol. The protocol uses a CHARMm-based molecular dynamics (MD) scheme to dock ligands into a receptor binding site (KPC-2). Random ligand conformations are generated using high-temperature MD. The conformations are then translated into the binding site. Candidate poses are created, using random rigid-body rotations followed by simulated annealing. A final minimization is then used to refine the ligand poses. In addition to the structural information, each record includes the CDOCKER score reported as the negative value (i.e., -CDOCKER_ENERGY), where a higher value indicates a more favorable binding. This enables the energy to be used like a score. This score includes internal ligand strain energy and receptor-ligand interaction energy and is used to sort the poses of each input ligand. The compounds with the best scoring function were analyzed, the covalent bond with S70 was form, and the enzyme-ligand complex was future minimized. To assess potential interactions and nonbound interactions between the receptor (KPC-2) and boronates, the receptor interaction surface was generated for different compounds (1 g, 1 e). To represent the flexibility of the W105 residue, the structures of KPC-2 and KPC-2 with vaborbactam (PDB ID: 6TD0) and taniborbactam (PDB ID: 6TDI) were superimposed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by facilities and funds provided by Department of Life Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia to E.C. (FAR 2016) and by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to R.A.B. under Award Numbers R01AI100560, R01AI063517, and R01AI072219. This study was also supported in part by funds and/or facilities provided by the Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs, Award Number 1I01BX001974 to R.A.B. from the Biomedical Laboratory Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development, and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center VISN 10. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under https://doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.202000126

References

- [1].World Health Organization. Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. Manual for Early Implementation. WHO 2015, 1–44. http://www.who.int/drugresistance/en/%5Cnwww.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.%5Cnhttp://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/188783/1/9789241549400_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Navon-Venetia S, Kondratyeva K, Carattoli A, FEMS Microb. Rev 2017, 41, 252–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Effah CY, Sun T, Liu S, Wu Y, Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob 2020,19, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stoesser N, Sheppard AE, Peirano G, Anson LW, Pankhurst L, Sebra R, Phan HTT, Kasarskis A, Mathers AJ, Peto TEA, Bradford P, Motyl MR, Walker AS, Crook DW, Pitout JD, Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 5917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Pasteran FG, Otaegui L, Guerriero L, Radice G, Maggiora R, Rapoport M, Faccone D, Di Martino A, Galaset M, Emerg. Infect. Diseas 2008, 14, 1178–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Porreca AM, Sullivan KV, Gallagher JC, Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep 2018, 20, 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Papp-Wallace KM, Expert Opin. Pharmacother 2019,20, 2169–2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ehmann DE, Jahic H’, Ross PL, Gu RF, Hu J, Kern G, Walkup GK, Fisher SL, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2012, 109 11663–11668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Stachyra T, Levasseur P, Phéchereau MC, Girard AM, Claudon M, Miossec C, Black MT, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2009, 64, 326–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Endimiani A, Choudhary Y, Bonomo RA, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2009, 53, 3599–3601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Humphries RM, Yang S, Hemarajata P, Ward KW, Hindler JA, Miller SA, Gregson A, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 6605–6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gaibani P, Campoli C, Lewis RE, Volpe SL, Scaltriti E, Giannella M, Pongolini S, Berlingeri A, Cristini F, Bartoletti M, Tedeschi S, Ambretti S, J. Antimicrob. Chemother 2018, 73, 1525–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Clancy CJ, Open Forum Infect. Dis 2017, 4, 22–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hecker SJ, Reddy KR, Totrov M, Hrst GC, Lomovskaya O, Griffith DC, King P, Tsivkovski R, Sun D, Sabet M, et al. , J. Med. Chem 2015, 58,3682–3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lamovskaya O, Sun D, Rubio-Aparicio D, Nelson K, Tsivkovski R, Griffith DC, Dudley MN, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2017, 61, e01443–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sun D, Rubio-Aparicio D, Nelson K, Dudley MN, Lamovskaya O,Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2017, 61, e01694–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wilson WR, Kline EG, Jones CE, Morder KT, Mettus RT, Doi Y, Nguyen MH, Clancy CJ, Shields RK, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2019, 63, e02048–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Romagnoli C, Caselli E, Prati F, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2015, 2015, 1075–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, Data from the EUCAST MIC distribution website, last accessed February 19th, 2020.

- [20].Bonandi E, Christodoulou MS, Fumagalli G, Perdicchia D, Rastelli G, Passarella D, Drug Discovery Today. 2017, 22, 1572–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Caselli E, Romagnoli C, Vahabi R, Taracila MA, Bonomo RA, Prati F, J. Med. Chem 2015, 58, 5445–5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Caselli E, Fini F, Introvigne ML, Stucchi M, Taracila MA, Fish E, Smolen KA, Rather PN, Powers RA, Wallar BJ, Bonomo RA, Prati F, ACS Infect. Dis 2020, accepted for publication. unpublished results. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Caselli E, Romagnoli C, Powers RA, Taracila MA, Bouza AA, Swanson HC, Smolen KA, Fini F, Wallar BJ, Bonomo RA, Prati F, ACS Infect. Dis 2018, 4, 337–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). 2014. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 24th informational supplement. CLSI, Wayne, PA. United Nations, 21 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Papp-Wallace KM, Taracila MA, Wallace C, Hujer KM, Bethel CR, Hornick M, Bonomo RA, Protein Sci. 2010, 19, 1714–1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rojas LJ, Taracila MA, Papp-Wallace KM, Bethel CR, Caselli E, Romagnoli C, Winkler ML, Spellberg B, Prati F, Bonomo RA, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 1751–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bouza AA, Swanson HC, Smolen KA, VanDine AL, Taracila MA, Romagnoli C, Caselli E, Prati F, Bonomo RA, Powers RA, Wallar BJ, ACS Infect. Dis 2018, 4, 325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA, Discovery Studio Modeling Environment, Release 2017, San Diego: Dassault Systèmes, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.