Abstract

Background:

Recent reports have suggested that insulin vials purchased in community pharmacies do not meet the minimum required intact insulin concentration (≥95 U/mL) as defined by the United States Pharmacopeia. We sought to independently obtain multidose human insulin vials from a variety of community pharmacies across the state of Washington and quantitatively measure intact insulin.

Methods:

Sixty 10-mL vials of insulin (n = 30 regular human insulin and n = 30 neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin) were purchased and assayed. To ensure random selection of lots and supply chain sources, insulin samples were purchased on a variety of calendar dates from various pharmacy locations across Washington State, inclusive of both chain and independent pharmacies. All samples were assessed for intact insulin concentration via both Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with UV detection (UPLC-UV) and Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS).

Results:

When considering all samples (N = 60), the mean concentration was 101.8 ± 4.4and 91.5 ± 1.9 U/mL as determined by UPLC-UV and UPLC-MS, respectively. Measured concentrations ranged from 90.0 to 108.4 U/mL when assayed by UV UPLC and 86.1 to 95.4 U/mL for UPLC-MS.

Conclusion:

To our knowledge, this is the first study following the report by Carter et al that assessed human insulin concentrations by both UPLC-UV and UPLC-MS. These findings are important because they demonstrate that the results obtained from these two methods differ and that the method used must be considered when interpreting findings.

Keywords: analysis, insulin, insulin concentration, quality assurance, vials

Introduction

Insulin therapy is a medical necessity for people living with type 1 diabetes mellitus and is utilized by many people with type 2 diabetes mellitus to meet individualized glycemic targets.1 Accurate dosing of insulin is critical to avoid unnecessary hyperglycemic and hypoglycemic fluctuations. Clearly, consistent and reliable insulin potency is critical to facilitate precise delivery of insulin to achieve consistent clinical response.

A recently published paper reporting significantly diminished potency of human insulin vials obtained from retail pharmacies has called into question the reliability of insulin potency in the products used by patients in the community.2 The study by Carter and Heinemann reported that when assayed for active insulin content, zero of 18 randomly acquired vials of human insulin met the minimum intact insulin concentration standard recognized by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of 95 U/mL.2 They reported intact insulin concentrations ranging from 13.9 to 94.2 U/mL in a total of 18 vials tested, with a mean of 40.2 U/mL. Following the publication of the Carter et al paper, several organizations responded with commentaries voicing concern about the validity of the reported findings. Methodological concerns were noted by the American Diabetes Association (ADA), including concerns about the small sample size and the analytical methods used.3 The ADA additionally voiced concern about the potential ramifications of the report to patient care such as undue patient anxiety and noncompliance or misuse of insulin by patients who believe that the potency of their insulin is less than indicated on the product label.3 Another commentary from Eli Lilly and Company also questioned the methods employed by Carter et al.4 The commentary noted that the Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry method used in the Carter et al paper was designed to measure insulin concentrations in human plasma and that sample preparation likely resulted in poor and varied recovery of insulin from the samples analyzed.4 Further, data reported from Novo Nordisk in response to the Carter et al study reported no loss of insulin potency based on the analysis of production batches tested over a seven-year period.5 The paper additionally reported that the intact insulin concentrations measured from a total of 233 insulin vials returned by patients to Novo Nordisk over the preceding three-year period were, without exception, within United States Pharmacopoeia (USP) requirements, and they suggested that the findings reported by Carter et al were likely due to the analytical methods employed and not due to an actual lack of potency in the vials tested.5 It should be noted that the report from Moses et al measured insulin concentrations via Reverse Phase-High Pressure Liquid Chromatography.

Given the clear importance of insulin potency to patient care, we sought to assess the potency of a larger sampling of human insulin vials purchased from pharmacies across the state of Washington. In consideration of the concerns raised about the analytical method used by Carter and Heinemann, we assessed insulin potency via both Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with UV detection (UPLC-UV) and Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS). In doing so, we endeavored to determine if the potency of human insulin purchased in the community was below the minimum standard of 95 U/mL and to compare the results obtained when assessing insulin concentration by two different analytical methods (UPLC-UV and UPLC-MS).

Methods

Sample Procurement

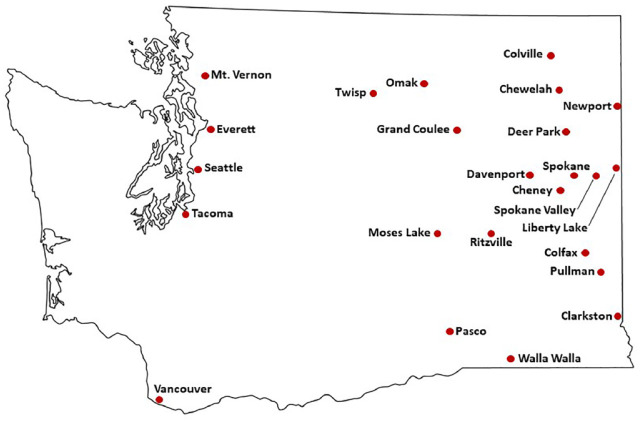

In the Washington State Insulin Concentration Study (WICS), sixty 10-mL vials of insulin (n = 30 regular human insulin [RHI] and n = 30 neutral protamine Hagedorn [NPH] insulin) were purchased from a variety of chain and independent pharmacies located in 24 cities or towns across the state of Washington (Figure 1). To encourage random selection of lots (batches) and supply chain sources, insulin samples were purchased on a variety of calendar dates during the months of October and November of 2018, and were inclusive of a random sampling of three different branded products (Novolin, Humulin, and ReliOn; Table 1). Insulin vials were purchased over-the-counter at the listed cash at the randomly selected pharmacies. All manufacturer recommended expiration dates fell after the date that potency analyses were completed.

Figure 1.

Sampling locations within the state of Washington. Insulin samples were purchased from 24 cities across the state of Washington.

Table 1.

Summary of Insulin Samples Obtained.

| Brand | Insulin type | Number of vials purchased | Number of individual lots (batches) sampled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novolin | RHI | 10 | 6 |

| NPH | 9 | 6 | |

| Humulin | RHI | 11 | 8 |

| NPH | 12 | 11 | |

| ReliOn | RHI | 9 | 4 |

| NPH | 9 | 4 |

Abbreviations: NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin; RHI, regular human insulin.

Immediately following purchase, all samples were stored within a portable refrigerator during transport back to the laboratory. All samples were then stored under continuously monitored (TandD TR-71wf Temperature Data Logger) refrigerated conditions between 2°C and 8°C until analyzed.

Chemicals and Materials

United States Pharmacopeia reference standard of human insulin standard (26.5 USP/mg), insulin from bovine pancreas, sodium sulfate, phosphoric acid, and hydrochloric acid were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, United States). Packing L1 column, Cortecs UPLC C18+ (1.6 µm, 2.1 × 50 mm, p/n 186007114), was purchased from Waters (Milford, MA, United States). Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry pure formic acid and acetonitrile were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, United States).

Analysis of Insulin Concentrations

Sample stock solution preparation

Regular human insulin or NPH samples were first mixed by inverting the sample bottle ten times. Each sample (1.0 mL) was transferred to a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube with an insulin syringe, followed by the addition of 2 µL of 12.1 N HCl to each mL of sample solution. Each sample was then mixed.

Human insulin standard curve solution preparation

Human insulin (100 mg; USP Reference Standard 1 mg = 26.5 USP insulin Human Units) was dissolved in 20 mL of 0.01 N HCl, resulting in a 5 mg/mL stock solution. Aliquots of 1 mL/tube were stored at –20°C. A series of standard solutions of 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, and 0.313 mg/mL human insulin standard was made by serial dilution of 5 mg/mL stock with 0.01 N HCl.

Internal standard (IS) solution preparation

Insulin from bovine pancreas (50 mg) was dissolved in 25 mL of 0.01 N HCl. Aliquots of 1 mL/tube were stored at –20°C.

Quantification of insulin by UPLC-UV method

Sample stock solution or standard curve solution (20 µL) was mixed with an equal volume of internal standard (IS) solution and was then transferred to a UPLC sample vial for UPLC-UV analysis. The Acquity UPLC system (Waters) used for this analysis was equipped with a binary solvent manager, an auto sampler, and a TUV detector. The LC method was adapted from USP monographs.6 The above samples were analyzed with a UPLC C18+ column (Cortecs, 1.6 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm, Waters) at 40°C using isocratic elution of 74% buffer A (2.7 mL phosphoric acid and 28.6 g of Na2SO4 in 1000 mL water) and 26% buffer B (100% acetonitrile) for six minutes with the flow rate set at 1 mL/min. The UV detection wavelength was set at 214 nm and the sample injection volume was 5 µL. The retention times for human insulin and IS (bovine insulin) were 4.18 and 2.93 minutes, respectively. The standard curve was plotted as the ratio of peak areas of human insulin and IS vs the concentration of human insulin in a series of standard solutions (5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, and 0.313 mg/mL).

Quantification of insulin by UPLC-MS method

Each sample (10 µL) and an equal volume of IS solution were added into 1000 µL of 0.01 N HCl solution in a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube. Following mixing, 200 µL of each mixture was transferred into a 350 µL conical glass sample vial. The UPLC-MS system (Waters) used for the analysis was equipped with an Acquity UPLC solvent manager, an FTN auto sampler, a UPLC C18+ column (Cortecs, 1.6 µm, 2.1×50 mm, Waters), and a Xevo G2S QTof mass spectrometer. The temperature in the sample manager was set at 15°C and the column temperature was 60°C. Due to the high sensitivity of the mass spectrometer, sample injection volume was set at a low value of 0.2 µL. The LC flow rate was 0.25 mL/min. The initial LC condition was 85% buffer A (0.1% formic acid) and 15% buffer B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile), with a linear gradient to 40% B in four minutes, followed by an isocratic gradient at 40% B for one minute, and re-equilibration with 85% buffer A for one minute before injection of the next sample. The Xevo-G2S QTof was operated in ESI positive ion MS scan sensitive mode, with the capillary voltage at 3 kV and the cone voltage at 40 V. Mass Spectrometry traces of m/z 1162.35 (5+ ion (5+)) and 1147.54 (5+ ion) were used for the detection of human insulin and IS (insulin bovine), respectively. Retention times for human insulin and insulin bovine were 2.77 and 2.68 minutes, respectively.

Results

Insulin human standard curves are linear within the measured range (0.3-5 mg/mL) as measured by UPLC-UV and UPLC-MS methods, with r2 equal to 0.9996 and 0.9997, respectively. A summary of measured insulin concentrations as determined by both UPLC-UV and UPLC-MS is provided in Table 2. The mean concentration of all 60 samples was 101.8 ± 4.4 and 91.5 ± 1.9 U/mL as determined by UPLC-UV and UPLC-MS, respectively. Measured concentrations ranged from 90.0 to 108.4 U/mL when assayed by UPLC-UV and 86.1 to 95.4 U/mL for UPLC-MS. No significant differences in insulin concentration were noted for either methods when samples were split by insulin type (RHI vs NPH; Table 2).

Table 2.

Measured Insulin Concentrations (U/mL).

| Insulin type | UPLC-UV method Mean ± SD (range) |

UPLC-MS method Mean ± SD (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Combined* (N = 60) | 101.8 ± 4.4 (90.0-108.4) | 91.5 ± 1.9 (86.1-95.4) |

| RHI (n = 30) | 101.9 ± 4.3 (90.0-108.0) | 91.8 ± 1.7 (88.3-94.9) |

| NPH (n = 30) | 101.6 ± 4.6 (93.3-108.4) | 91.2 ± 2.1 (86.1-95.4) |

Abbreviations: NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin; RHI, regular human insulin; SD, standard deviation; UPLC-MS, Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry; UPLC-UV, Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with UV detection.

Includes all RHI and NPH samples.

When considering the minimum intact insulin concentration standard recognized by the FDA, a total of five of the 60 samples tested below 95 U/mL threshold as determined by UPLC-UV when rounded to the nearest full unit/mL. Those samples that tested below 95 U/mL all tested at a concentration of 90 U/mL or above (90, 91, 93, 94, and 94 U/mL, respectively). When assayed by UPLC-MS, the mean insulin concentration was measured at 91.5 ± 1.9 with 57 of the 60 samples testing below the 95 U/mL threshold when rounded to the nearest unit/mL (Table 2).

Discussion

Our assessment of human insulin concentrations from vials obtained randomly from pharmacies across the state of Washington showed that the large majority of samples were above the FDA minimum concentration threshold of 95 U/mL when measured by UPLC-UV. When assayed by UPLC-MS, the measured intact insulin concentrations were slightly lower, with a mean measured concentration of 91.5 U/mL for 60 insulin vials tested. While the UPLC-MS method is superior in sensitivity, the UPLC-MS measurement could be slightly less accurate in comparison with the UPLC-UV method. While insulin bovine is an ideal IS for UV quantification, it may not be ideal for UPLC-MS analysis due to potential matrix effects that could affect the accuracy of the UPLC-MS measurement. Mass Spectrometry signal strength depends on ionization efficiency, which can be affected by matrix co-elution. The LC retention time for human insulin and bovine insulin differs, therefore, ionizing efficiency for human insulin and bovine insulin may be affected differently due to differences in matrix effects. Quantification was based on the ratio between peak area of human insulin and bovine insulin. The standard curve solutions were prepared from pure human insulin standard, but the insulin specimens contain other compounds and additives as matrix. We speculate that this matrix difference between the insulin standard curve solution and samples, to some extent, could have affected the accuracy of the insulin quantification by UPLC-MS. In contrast, at the high levels of insulin measured in this study, the UPLC-UV methodology employed is extremely accurate since matrix effects do not play a role when quantifying by UV absorbance.

Carter et al reported the intact insulin concentrations ranging from 13.9 to 94.2 U/mL, with a mean of 40.2 U/mL for the 18 samples tested via UPLC-MS.2 While this method is highly sensitive, it has not been validated against the USP standard to quantify insulin concentration.6 Indeed, our findings suggest that the assessment of human insulin concentrations by UPLC-MS results in only slightly lower measured insulin concentrations when compared to UPLC-UV. While our UPLC-MS results found a range of intact insulin concentrations ranging from 86.1 to 95.4 U/mL, our measured concentrations were no more than 10% lower than the FDA minimum concentration threshold of 95 U/mL. This contrasts with the mean 2.4-fold decrease observed in the Carter and Heinemann study using the same method.

Conclusion

Results from WICS provide an assessment of human insulin concentrations via two analytical methods in a sample of 60 human insulin vials obtained randomly from pharmacies across Washington state. To our knowledge, this is the first study following the report by Carter et al that assessed human insulin concentrations by both UPLC-UV and UPLC-MS. These findings are important because they demonstrate that while the results obtained from these two methods differ slightly, in both cases the measured insulin levels are within 90% of the FDA minimum concentration threshold of 95 U/mL for all 60 samples tested. This contrasts with the mean 2.3-fold decrease in insulin levels observed by Carter et al. It should be noted that these assays measure insulin concentrations in solution and may or may not relate to biological activity. As noted in the letter from the ADA in response to the Carter and Heinemann study, the ADA, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, and the Helmsley Charitable Trust are working together to commission an independent evaluation of insulin concentrations from insulin obtained from manufacturers and retail pharmacies. Findings from this larger study will provide additional insight into this important question of insulin potency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Abby Parsons for her organizational support of this study. We would additionally like to thank supporters of the R. Keith Campbell Distinguished Professorship and the Allen I. White Distinguished Associate Professorship.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: JJN, GC, CN, SH, and PL disclose no relevant conflicts of interest related to the content of this article. JW has served as a consultant to Sanofi-Aventis, LLC.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported internally by the College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at Washington State University through funds from the R. Keith Campbell Distinguished Professorship (held by JRW) and the Allen I. White Distinguished Associate Professorship (held by JJN).

ORCID iD: Joshua J. Neumiller  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4734-7402

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4734-7402

References

- 1. American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S90-S102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carter AW, Heinemann L. Insulin concentration in vials randomly purchased in pharmacies in the United States: considerable loss in the cold supply chain. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(4):839-841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Petersen MP, Hirsch IB, Skyler JS, Ostlund RE, Cefalu WT. In response to Carter and Heinemann: insulin concentration in vials randomly purchased in pharmacies in the United States: considerable loss in the cold supply chain. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(4):890-891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Connery A, Martin S. Lilly calls into question the validity of published insulin concentration results. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(4):892-893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moses A, Bjerrum J, Hach M, Wæhrens LH, Toft AD. Concentrations of intact insulin concurs with FDA and EMA standards when measured by HPLC in different parts of the distribution cold chain. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2019;13(1):55-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. US Pharmacopeia. Insulin Human Drug Products 100 IU/ml. Rockville, MD: US Pharmacopeia; 2016. [Google Scholar]