Abstract

A physiologic increase in reactive oxygen species throughout pregnancy is required to remodel the cervix. Oxidative stress can cause cellular damage that contributes to dysfunctional tissue. This study determined the oxidative stress-induced cell fate of human cervical epithelial and cervical stromal cells. We treated the ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells with cigarette smoke extract, an oxidative stress inducer, for 48 h. Cell viability (crystal violet assay); cell cycle, apoptosis, and necrosis (flow cytometry); senescence (senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining); autophagy (staining for autophagosome protein, microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3B); stress signaler p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases pathway activation (western blot analyses); and inflammation by measuring interleukin-6 (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) were conducted after 48 h of cigarette smoke extract treatment. Oxidative stress induced reactive oxygen species production in cervical cells, which was inhibited by N-acetylcysteine. Oxidative stress promoted cell cycle arrest and induced necrosis in cervical cells. High senescence and low autophagy were observed in cervical stromal cells under oxidative stress. Conversely, senescence was low and autophagy was high in endocervical epithelial cells. Oxidative stress induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases (p38MAPK) activation in all cervical cells but only increased interleukin-6 production by the ectocervical epithelial cells. Inhibition of interleukin-6 production by a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases inhibitor confirmed the activation of an oxidative stress-induced pathway. In conclusion, oxidative stress can promote cell death and sterile inflammation that is mediated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases activation in the cellular components of the cervix. These cellular damages may contribute to the normal and premature cervical ripening, which can promote preterm birth.

Keywords: apoptosis, autophagy, cell death, necrosis, senescence

Oxidative stress can promote different forms of cell death (apoptosis, necrosis, sensescence, and autophagy) and sterile inflammation that is mediated by p38MAPK activation in the cellular components of the cervix.

Introduction

During pregnancy, the cervix is the mechanical barrier that must remain firm and closed to keep the fetus safely in utero [1]. As the pregnancy approaches full term, the cervix must remodel/soften and dilate in order for parturition to occur. When this remodeling process is triggered prematurely, resulting in premature cervical shortening and failure, the pregnancy is at increased risk for preterm birth [2]. Since preterm birth significantly increases a baby’s risk for neonatal demise or lifelong comorbidity [3–5], it is imperative that we better comprehend the process of normal and premature cervical remodeling and function in human pregnancy. Although various hypotheses exist as to what may trigger resident cervical cells to start the process of normal or pathologic cervical remodeling, the exact mechanisms remain unclear [6, 7].

Oxidative stress (OS), an imbalance of free radicals and antioxidants in the body that can lead to cell and tissue damage, is associated with preterm labor and preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (pPROM) [8, 9]. It is clear from previous studies that OS has detrimental effects on placental, uterine, and fetal tissues, which can lead to preterm birth [10–12]. However, it is not yet clear whether OS influences cervical function, specifically remodeling, during pregnancy [13]. Several studies have suggested that OS may be involved in cervical remodeling during pregnancy [14–16]. Glutaredoxin, an antioxidant enzyme, was shown to be increased in cervical biopsies from women with term pregnancies and immediately postpartum [14]. This enzyme has a role in repairing damaged proteins due to OS. Women with higher maternal serum levels of OS markers as indicated by high CRP and lipid peroxide levels and low ORAC levels were at increased risk for preterm delivery [15]. The total antioxidant capacity, including copper, zinc, superoxide dismutase, and thioredoxin-1 levels, in the cervicovaginal fluid significantly decreases with the onset of labor. The suppressed level of the antioxidant capacity may be linked to the gradual ripening of the cervix during parturition [16]. The different risk factors that predispose patients to preterm birth, such as infection, sterile inflammation, obesity, gestational diabetes mellitus, and preeclampsia, are associated with increased OS [17–22]. However, information regarding the levels of OS and the effects of OS on the cell fate of cervical tissues during pregnancy is still missing.

The results from previous studies are conflicting and further studies are warranted to delineate the potential association between OS and cervical remodeling and function during normal pregnancy and those with premature cervical remodeling/failure leading to spontaneous preterm birth. This study fills this vital knowledge gap and has established the effects of OS on the cell fate of human cervical epithelial and stromal cells. This study showed that OS can promote cell death; can increase apoptosis, necrosis, senescence, and autophagy; and can promote inflammation in cervical epithelial and stromal cells. Oxidative stress also significantly increased the p38MAPK pathway, which suggests a potential role of this pathway in OS-induced inflammation and cell death.

Materials and methods

Human ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cell and cervical stromal cell cultures

Immortalized ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells were provided by Dr. Richard Pyles (the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, TX, USA). These cell lines were previously validated to model lower genital epithelial cells [23, 24]. Ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells were cultured in keratinocyte serum-free medium (KSFM), a culture medium highly selective for epithelial cells, supplemented with bovine pituitary extract (30 μg/mL), epidermal growth factor (0.1 ng/mL), CaCl2 (0.4 mM), and primocin (0.5 mg/mL) (ant-pm-1; Invivogen; San Diego, CA).

Using IRB-approved protocols (IRB-AAAI0337), primary cervical stromal cells were isolated from cervical tissue biopsies obtained from nonpregnant, premenopausal women (<50 years old) undergoing total hysterectomy due to benign gynecological conditions at the Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Women with a history of cervical surgery (loop electrosurgical excision procedure/cone biopsy) or a recent abnormal Pap smear were excluded. Informed consent with written documentation was obtained from all research participants. Immediately after the hysterectomy specimen was removed from the patient, a cervical tissue sample (full thickness sample about 2 cm long) was collected from the area of the external os to mid-cervix (parallel to the endocervical canal) and was placed in a pre-cooled freezing medium (90% fetal bovine serum [FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.] with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide [Me2SO]). Samples were frozen at −80°C and were then sent to the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

To prepare primary cells for culture, cervical tissues were thawed in a water bath at 37°C. The cervical epithelium was removed, and the cervical stromal layer was incubated in 15 mL complete cervical stromal cell medium composed of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 media (DMEM/F12; Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA) was supplemented with 10% FBS, 10% penicillin/streptomycin (Mediatech Inc.), and 10% amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.), at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 10 min. Three successive transfers of 15 mL fresh cervical stromal media were done on the cervical stromal tissues. The cervical stromal tissue was then cut into small fragments (1 × 1 mm) and was incubated with collagenase (0.15% in DMEM without serum) at 37°C for 1 h. An equal volume of complete cervical stromal cell medium was then added to neutralize collagenase and was filtered through 70-μm nylon mesh. The cell digest was centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min, and the cell pellets were grown in complete cervical stromal cell medium at 37°C and 5% CO2 until it reached 80% confluence.

To determine the purity of the immortalized cell lines, immunocytochemical staining for vimentin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and cytokeratin-18 (CK-18, Abcam) were performed as previously described [25]. Ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells were seeded into an 8-well slide and grown to 80% confluence. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X, and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The dilution used for CK-18 was 1:500 (in 3% BSA) and for vimentin was 1:300 (in 3% BSA). After washing with 1× PBS, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated and 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted 1:400 in 1× PBS for 2 h in the dark. The cells were washed with 1× PBS, and then treated with NucBlue Fixed Cell Stain ReadyProbes reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to stain the nucleus. Fluorescence microscopy images were captured using a Keyence BZ-X810 All-in-One Fluorescence Microscope (20×).

Immortalization of primary cervical stromal cells was done using the hTERT Cell Immortalization Kit (ALSTEM Inc., Richmond, CA). PolyA RNA sequencing was performed to compare the gene expression profiles of primary and immortalized cervical stromal cells. The genes, transcript range, and expression density are similar between the immortalized and primary human cervical stromal cell lines (Supplementary Figure S1A and B). Only <1% of the total genes are differentially expressed between primary and immortalized human cervical stromal cells, with a Pearson’s correlation analysis result of 0.885 (Supplementary Figure S1C). Immunocytochemical staining also showed that both primary and immortalized cervical stromal cell lines express vimentin, a mesenchymal marker (Supplementary Figure S1D). This shows that the immortalized human cervical stromal cells can be used as an in vitro model for the primary human cervical stromal cells.

Stimulation of cervical cells with water-soluble cigarette smoke extract

To induce OS in the cervical cells, we included cigarette smoke extract (CSE) treatment in our experimental design [26, 27]. To produce water-soluble CSE, smoke from a single lit commercial cigarette (unfiltered Camel, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., Winston-Salem, NC) was bubbled through 25 mL of media consisting of KSFM for the epithelial cells and complete cervical stromal cell medium for the stromal cells. The stock CSE was sterilized using a 0.22-μm Steriflip filter unit (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Cigarette smoke extract concentrate was diluted 1:50 (for 48 h treatment) in complete media prior to use. Approximately, 300 000 cervical epithelial cells and 500 000 cervical stromal cells were cultured in a six-well plate for 48 h CSE treatments. The cells were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% air humidity for 48 h.

Inhibition of p38MAPK activation by N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), a potent antioxidant, was used to verify the influence of treatment-induced OS on cell fate [26, 28]. N-acetylcysteine (5 mM) (#A7250-SG) was added to the treatment media of the cervical cells treated with the reagents as described above. The cells were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% air humidity for 48 h.

Measurement of ROS

Cervical epithelial and stromal cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (10 000 cells per well), grown to 90% confluence, loaded with 50 mM of 2′7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCF) diacetate (#C400, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and incubated at 37°C for 30 min [26]. Cells were subsequently exposed to CSE or a combination of CSE and NAC (5 mM) for up to 2 h. Fluorometric measurements were taken at 5 min, then every 10 min for 1 h and after 2 h to determine changes in the ROS levels. Dichlorodihydrofluorescein fluorescence was recorded in an FL×800™ microplate reader at 528 nm after excitation at 485 nm. Results were expressed as arbitrary units, calculated using the mean slope of a linear regression of all points within the calculation zone.

Crystal violet cell viability assay

Cervical epithelial and stromal cells were seeded in a 48-well plate (25 000 per well) and were exposed to different treatments described as above for 6 days. At the end of the experiment, cells were washed with 1× PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed again with 1× PBS, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min. After 20 min, cells were washed, allowed to dry, and 10% acetic acid was added to each well. A 1:4 dilution of the colored supernatant was measured at an absorbance of 590 nm. Untreated cells maintained in standard cell culture conditions were used as controls.

Cytologic senescence-associated β-galactosidase assay

To determine senescence in cervical epithelial and stromal cells after treatment with CSE, senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA β-gal) staining was performed using a commercial histochemical staining assay, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Senescence Cells Histochemical Staining Kit; Sigma-Aldrich) [27]. Briefly, ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stroma cells cultured in a six-well plate were washed twice with 1× PBS, fixed for 7 min with the provided fixation buffer, washed again with 1× PBS, and incubated overnight at 37°C with fresh β-Gal solution. Following incubation, cells were evaluated using a standard light microscope.

Immunocytochemical staining for LC3B

To determine autophagy in cervical epithelial and stromal cells, we performed immunocytochemical staining for human LC3B Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated antibody (R&D Systems, city, state) after 48 h of exposure to treatment conditions as described above. The LC3B is a common marker for autophagic structures [29]. After 48 h of exposure, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X, and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS before incubation with primary antibody (1:100 dilution) overnight at 4°C. After washing with 1× PBS, slides were incubated with the primary antibody. Slides were washed with 1× PBS, treated with NucBlue Fixed Cell Stain ReadyProbes reagent, and then mounted using Mowiol 4 to 88 mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich).

Microscopy and image analysis

Fluorescence microscopy images were captured using a Keyence BZ-X810 All-in-One Fluorescence Microscope. Three random regions of interest per field were used to determine yellow (LC3B) fluorescence intensity. Uniform laser settings, brightness, contrast, and collection settings were matched for all images collected. Images were not modified (brightness, contrast, and smoothing) for intensity analysis. ImageJ software version 1.51 J (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij) was used to measure LC3B staining intensity from three different regions per treatment condition.

Flow cytometry assays

Apoptosis and necrosis

To determine the population of cells undergoing apoptosis and/or necrosis, cells were stained using the Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit with Annexin V Alexa Fluor 488 & PI (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) as reported previously [30, 31]. Briefly, cells were harvested by trypsinization and centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 × g. Cell pellets were washed with cold 1× PBS and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min. Pellets were resuspended in 100 μL 1× annexin binding buffer supplemented with 5 μL Alexa Fluor 488 Annexin V and 1 μL 100 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI). After a 15-min incubation, 400 μL annexin binding buffer was added, and samples were run immediately on the CytoFlex flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). Unstained cervical cells were used as negative controls for gating. Data were analyzed using CytExpert software (Beckman Coulter).

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed using the flow cytometer, as described previously, using the Coulter DNA Prep Reagents Kit (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) [30]. Briefly, cells were harvested by trypsinization and centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 × g. Cell pellets were washed with cold 1× PBS and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min. Cell pellets were fixed with 500 μL 70% ethanol for 15 min. Cell pellets were washed with cold 1× PBS and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min. Then, 500 μL of the prep stain was added to the tubes, vortexed, and run immediately on the CytoFlex flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). After selecting for single cells, gating was set for the control cells and applied to histograms for each of the treatments in different cervical cells using CytExpert (Beckman Coulter). Cycle analysis by measuring DNA content was used to distinguish between different phases of the cell cycles. Fluorescence intensity, which directly correlated with the amount of DNA contained in a cell, was measured. Concurrent parameter measurements made it possible to discriminate between the S, G2, and mitotic cells. As the DNA content doubles during the S phase, the intensity of the fluorescence increases, making it possible to ascertain the action of CSE on cell proliferation.

Protein extraction and immunoblot assay

After 48 h of treatment, cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and 1.0 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The lysate was collected after scraping the culture plate, and the insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 9000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected, and protein concentrations in each lysate were determined using Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay Kits (Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The protein samples (20 μg) were separated using SDS-PAGE on a gradient (4–15%) with Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to the membrane using the iBlot Gel Transfer Device (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) and 5% skim milk for 2 h at room temperature. Blots were incubated separately with antibodies against total p38MAPK (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, 1:1000), phosphorylated (P)-p38MAPK (Cell Signaling, 1:300), and β-actin (A5441, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:15 000) at 4°C and shaken overnight. The membrane was incubated with appropriate peroxidase-conjugated IgG secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. All blots were developed using the chemiluminescence reagents ECL Western Blotting Detection System (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. The stripping protocol followed the instructions of the Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher). No blots were used more than three times. Densitometry was performed to normalize the data for statistical analysis.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human interleukin-6

Culture media were collected from ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells after 6 h of exposure to the treatment conditions indicated above. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to determine the levels of interleukin (IL)-6, as a marker of inflammation. Standard curves were developed with duplicate samples of known quantities of recombinant proteins that were provided by the manufacturer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Sample concentrations were determined by relating the absorbance values that were obtained to the standard curve by linear regression analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed for significant differences using GraphPad Prism software version 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality was done to check for the normality of the data. Parametric tests, including one-way analysis of variance followed by the Tukey multiple comparison post hoc test and the t-test, were used for the comparison of results for normally distributed data. Non-parametric tests, namely, Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test and Mann–Whitney U test, were used for comparison of the results for data that were not normally distributed. Statistically significant difference is indicated by a p < 0.05.

Results

To determine the effect of OS in the cervix, we treated the ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stroma cells with CSE (1:50) for 48 h to induce OS and sterile inflammation. We chose the 48-h time point based on prior data, where we showed that CSE increased the ROS, promoted senescence, and generated sterile inflammation in fetal membrane and placental cells and tissues [26, 27]. After 48-h treatment, we checked for cell viability using the crystal violet cell proliferation assay; apoptosis and necrosis and cell cycle analyses using flow cytometry; senescence using β-Gal histochemical staining, autophagy using LC3B immunocytochemistry, p38MAPK activation using western blot analysis; and IL-6 production using ELISA.

We first confirmed the epithelial and mesenchymal characteristics of cells used for our studies using specific markers. Ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells both expressed CK-18 and vimentin (Supplementary Figure S2). Cervical stromal cells only expressed vimentin and not CK-18 (Supplementary Figure S2).

CSE increases ROS production in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells

Cigarette smoke extract treatment increased the ROS production in all types of cervical cells as early as 5 min after the treatment (Supplementary Figure S3). The ROS production was persistently elevated in all cells until 2 h of treatment with CSE compared to that in the untreated control. However, CSE and NAC co-treatment decreased the ROS production in all cervical cells. Among the three cervical cells used, cervical stromal cells had the highest baseline and CSE-induced ROS production.

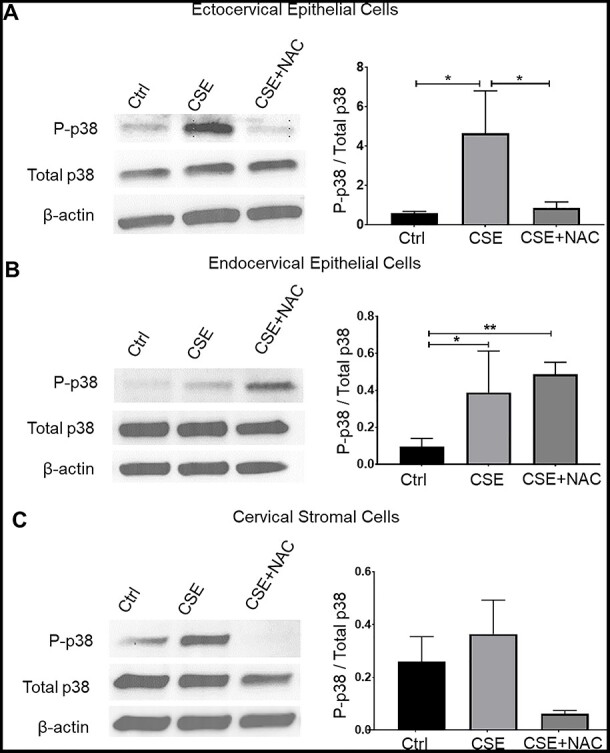

CSE promotes p38MAPK pathway activation in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells

Next, we tested OS-induced stress signal activation by determining p38MAPK by western blot analysis. Cigarette smoke extract induced the activation of p38MAPK in all three cervical cell types. Cigarette smoke extract significantly increased the phosphorylated p38MAPK (P-p38MAPK) in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells compared to that in the untreated control (p < 0.05 for both) (Figure 1A and B). A 1.4-fold increase in P-p38MAPK was observed in CSE-treated cervical stromal cells compared to that in the untreated cells, but it did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1C). N-acetylcysteine treatment significantly decreased the level of P-p38MAPK in ectocervical epithelial cells compared to that in CSE-treated cells (p < 0.05) and led to a 6-fold decrease in P-p38MAPK in cervical stromal cells. However, NAC treatment did not inhibit the activation of p38MAPK pathway in endocervical epithelial cells.

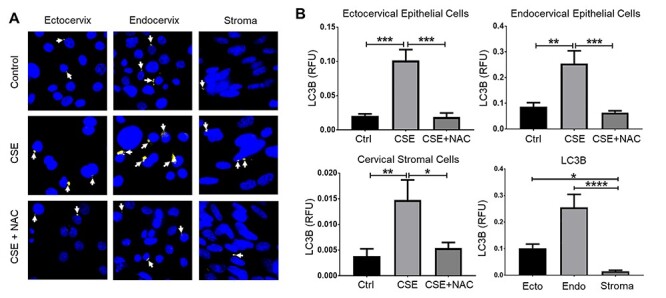

Figure 4 .

Cigarette smoke extract increased autophagy in cervical cells. (A) Fluorescence microscopy imaging showing LC3B (white arrows) in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells treated with control media (ctrl), CSE, and CSE + NAC for 48 h. Nuclei are stained with DAPI. Image, n = 3 biological replicates. Scale bar = 25 μm. (B) Quantification of the LC3B fluorescence intensity in (A). Values are expressed as mean relative fluorescence unit (RFU) of LC3B ± SEM. n = 9 technical replicates. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

Figure 1 .

Cigarette smoke extract induces p38MAPK activation in cervical epithelial and stromal cells. Western blot analysis and quantification of vimentin in ectocervical epithelial cells (A), endocervical epithelial cells (B), and cervical stromal cells (C) treated with control media (ctrl), CSE, and CSE + NAC for 48 h. β-actin is a loading control. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. n = 3 biological replicates. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

CSE decreases the viability of ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells

To determine the effects of CSE on cervical cell proliferation, we performed crystal violet assay tests on cervical cells treated with CSE. Oxidative stress, induced by CSE treatment, significantly decreased the number of viable ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells compared to those in the control as shown by the crystal violet cell proliferation assay (p < 0.0001 for all cell types) (Supplementary Figure S4). Co-treatment with CSE and NAC significantly increased the number of viable ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells compared to those in CSE treatment alone (p < 0.01, p < 0.01, and p < 0.05, respectively). Although the increase in viable cells did not reach the level of cell viability observed in the untreated control, the improvement after NAC treatment is indicative of the impact of OS on cells. We also observed that the cervical epithelial cells were more susceptible to OS compared to the cervical stromal cells. We saw the greatest reduction in cell viability, 95.11%, in CSE-treated endocervical epithelial cells, followed by ectocervical epithelial cells with a 74.14% reduction, and the cervical stromal cells, with only a 69.4% reduction in cell viability compared to those in the untreated control.

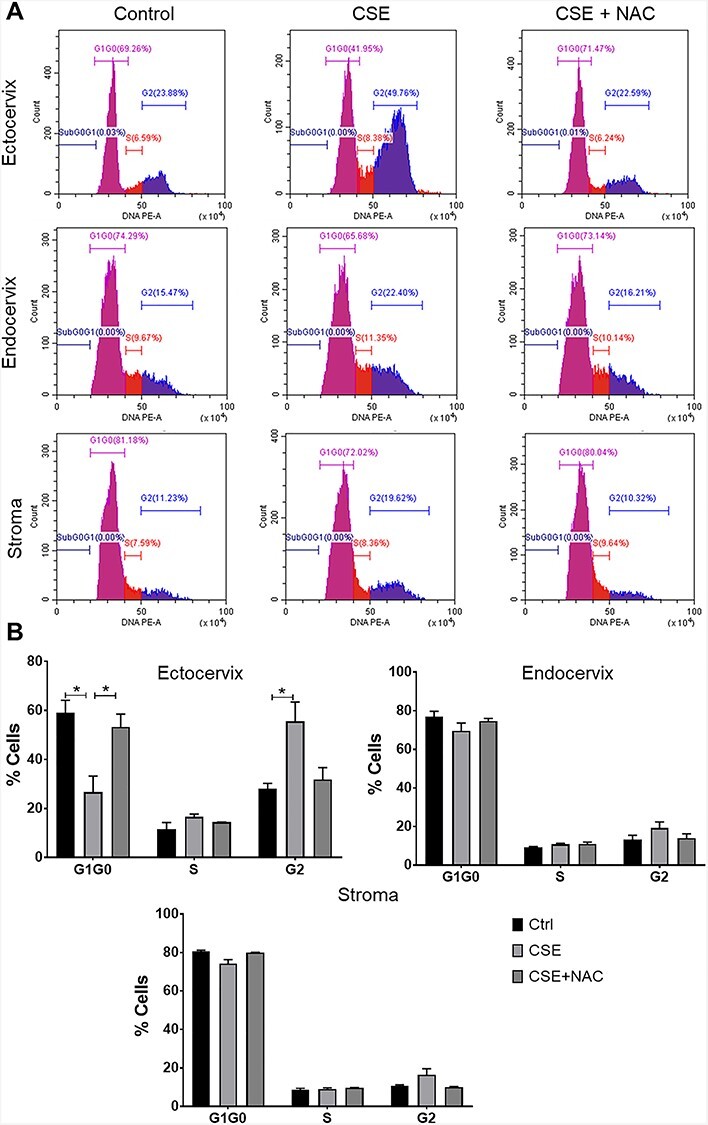

OS induces cell cycle arrest in ectocervical epithelial cells

To determine cervical cell fate in response to CSE treatment, we used flow cytometry to identify changes in the cell cycle progression in cervical cells (Figure 2). We observed significantly fewer ectocervical epithelial cells in the G1G0 phase (p < 0.05) and an increased number of cells in the G2 phase (p < 0.05) with CSE treatment compared to those in the control. Cigarette smoke extract did not change the number cells in S phase. N-acetylcysteine prevented this shift in cell cycle progression in the ectocervical epithelial cells. We did not observe a significant change in the cell cycle progression of endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells after CSE treatment.

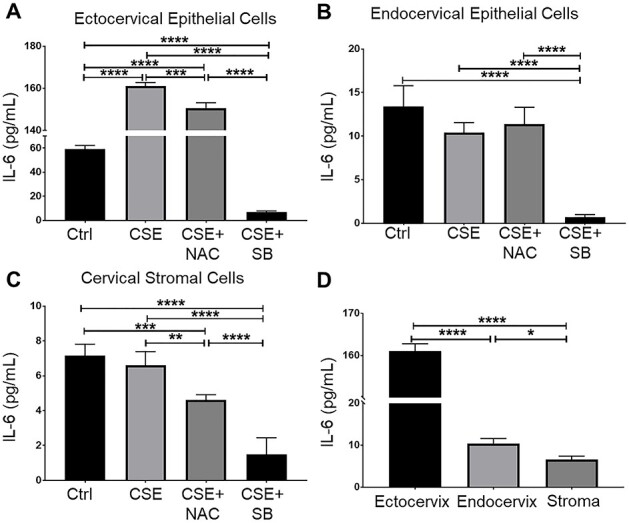

Figure 6 .

Interleukin-6 production of CSE-treated cervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-measured media concentrations of IL-6 from ectocervical (A) and endocervical epithelial cells (B) and cervical stromal cells (C) treated with control media (ctrl), CSE, and CSE with SB203580 (SB), a p38MAPK inhibitor (CSE + SB). (D) Comparison of IL-6 production by all cervical cell types treated with CSE. Values are expressed as mean IL-6 concentration ± SEM. n = 5 biological replicates. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

Figure 2 .

Cigarette smoke extract disrupted the cell cycle progression of cervical cells. (A) Flow cytometric cell cycle analysis of cervical cells in response to treatment with control media, CSE, and NAC for 48 h. (B) Quantification of cell cycle progression of cervical epithelial and stromal cells treated with control media (ctrl), CSE, and CSE + NAC for 48 h. *, p < 0.05.

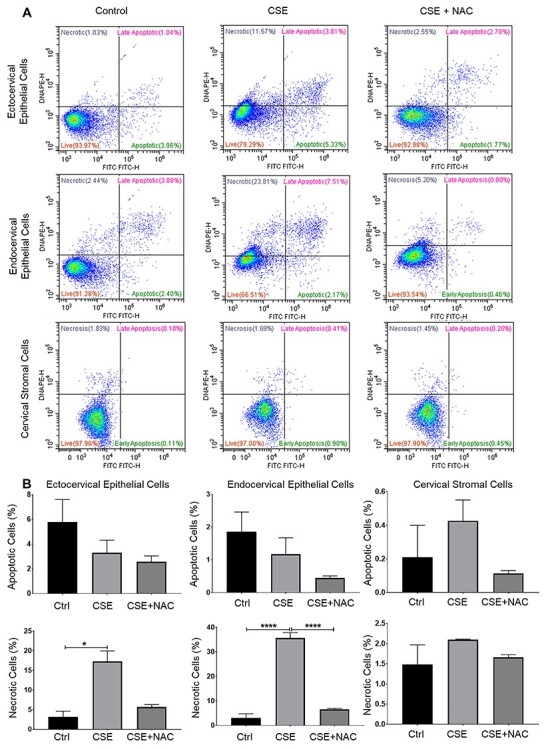

CSE increases apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells

To check whether OS can induce apoptosis and necrosis in cervical cells, we performed an apoptosis and necrosis analysis using flow cytometry. Our analysis showed that CSE promoted necrosis but not apoptosis in ectocervical (p < 0.05) and endocervical epithelial cells (p < 0.0001) and cervical stromal cells (p < 0.05) (Figure 3). N-acetylcysteine treatment reversed the effects of CSE-induced necrosis in all cervical cells. Despite the significant increase in necrosis, it should be noted that the apoptotic and necrotic cells only accounted for only 20–40% of the total cell population. The majority of the cells are still viable and are capable of remodeling and producing inflammatory signals.

Figure 3 .

Cigarette smoke extract increased apoptosis and necrosis in cervical epithelial cells. (A, B) Flow cytometric analysis of ectocervical epithelial cells, endocervical epithelial cells, and cervical stromal cells treated with control media (ctrl), CSE, and CSE + NAC for 48 h. Values are expressed as mean % cells ± SEM. n = 3 biological replicates. *, p < 0.05; ****, p < 0.0001.

Autophagy preserves cellular homeostasis by eliminating damaged proteins and organelles; however, excessive autophagy can also promote cell death [32]. To determine if OS can affect autophagy in cervical cells, we performed immunocytochemistry to detect LC3B, a ubiquitin-like modifier involved in the formation of autophagosomal vacuoles. We observed a significant increase in LC3B expression in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells treated with CSE compared to those in the untreated control (p < 0.01 for all) (Figure 4). This effect was blunted by treatment with NAC. A significant decrease in LC3B expression was observed in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, and p < 0.05, respectively). CSE-treated ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells showed significantly higher LC3B expression compared to that in CSE-treated cervical stromal cells (p < 0.05 and p < 0.0001, respectively). This showed that OS can induce autophagy in cervical cells. Endocervical epithelial cells, which had the highest level of OS-induced necrosis, also exhibited the highest level of autophagy, while the cervical stromal cells with the lowest level of OS-induced necrosis also had low levels of autophagy.

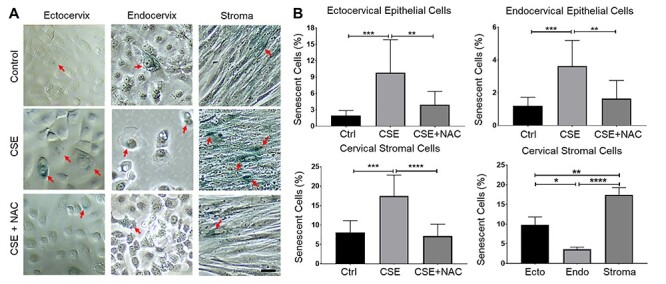

CSE promotes senescence in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells

Senescence is a mechanism of aging and cells do not die when undergoing senescence; however, they persist in the tissue and create an inflammatory environment. All cervical cell types were stained using SA-β-Gal (blue staining) to determine the CSE-induced senescence (Figure 5A and B). We observed a significant increase in senescence in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells treated with CSE compared to that in untreated cells (p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively). However, NAC treatment significantly decreased the number of senescent cells compared to those in CSE-treated ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells (p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001, respectively), confirming an OS effect. Cervical stromal cells showed the greatest increase in senescence in response to CSE, followed by the ectocervical epithelial cells, with the lowest percentage of cells with senescence being observed in endocervical epithelial cells.

Figure 5 .

Cigarette smoke extract induced senescence in cervical cells. (A) SA B-Gal staining in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells under normal culture conditions (control media [ctrl]), treated with CSE, and co-treated with CSE + NAC for 48 h. The red arrow indicates senescent SA B-Gal positive cervical cells. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Quantification of senescent cells in (A). Error bars represent mean senescent cells % ± SEM. n = 9 technical replicates. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001.

CSE increased the IL-6 production by ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells

Cigarette smoke extract significantly increased the IL-6 production of the ectocervical epithelial cells (p < 0.0001) compared to that in the untreated cells. N-acetylcysteine treatment significantly decreased IL-6 production compared to that in the CSE-treated ectocervical epithelial cells (p < 0.01) but was not sufficient to reduce the IL-6 to the baseline levels (Figure 6A). Cigarette smoke extract did not increase IL-6 production by the endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells; hence, no changes in IL-6 were also observed when these cells were co-treated with NAC (Figure 6B and C). Treatment with SB203580, a p38MAPK inhibitor, significantly decreased the IL-6 production to a level even lower than the baseline IL-6 levels in ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells (p < 0.0001 for all cell types). Inhibition of OS via NAC treatment did not prevent inflammation, but inhibition of the p38MAPK pathway through SB203580 treatment prevented inflammation in cervical cells.

Discussion

A balance between ROS and antioxidants is required for tissue remodeling and growth during pregnancy; however, OS and a redox imbalance have been shown to be associated with the timing of parturition [9, 10], as previous studies showed OS and a redox imbalance in response to various pregnancy risk factors can prematurely accelerate senescence and inflammation in the fetal membranes to increase the risk of preterm birth and pPROM [33–35]. However, the effect of OS on normal and premature cervical remodeling remains unknown.

In this study, we filled this vital knowledge gap by investigating the effects of OS on cervical cell fate (cell viability, p38MAPK activation, apoptosis, necrosis, autophagy, and senescence) and inflammation in human ectocervical and endocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells. Our main findings were as follows: (1) OS increased ROS production and activated the p38MAPK pathway in all three cervical cells; (2) OS promoted cell cycle arrest in ectocervical epithelial cells; (3) OS induced necrosis in cervical cells; (4) high level of senescence and low level of autophagy were observed in cervical stromal cells under OS. Conversely, low level of senescence and high level of autophagy were observed endocervical epithelial cells; and (5) OS increased p38MAPK-mediated sterile inflammation in cervical cells. In summary, this study showed resident cell types in the cervix exhibit a differential response to OS. The different forms of cell death and inflammation in specific cervical cells may be involved in the cervical remodeling process during pregnancy and parturition.

Apoptosis and necrosis in the resident cervical cell types may contribute to cervical tissue remodeling during pregnancy. Human cervical stromal biopsies from pregnant women in active labor have shown higher numbers of apoptotic nuclei compared to those from cervixes not in labor [36]. Oxidative stress levels are also increased, contributing to redox imbalance during parturition [37], and this increase is one of the initiators of labor [9]. In our study, the number of cervical cells undergoing apoptosis were negligible. This is an indication that, under OS conditions, cervical cells program themselves to remodel to minimize the risk of postpartum tissue damage.

Senescence in maternal and fetal cells is linked with preterm birth [38, 39]. Senescent uterine cells can produce a senescence-associated secretory phenotype, primarily uterotonics, including prostaglandins, to promote parturition [40–42]. However, senescence in cervical cells and its implication in pregnancy and parturition have not yet been documented. Our study suggests that the cervix is not just a passive responder to inflammatory signals released by the other maternal and fetal cells. Cervical epithelial and stromal cells can also undergo senescence in response to OS via the activation of the p38MAPK pathway, endogenously generating the inflammation required to transition the cervix from quiescent to an active state for fetal delivery.

Autophagy is a cellular process that maintains homeostasis in response to stress [43] by removing damaged organelles and by preventing cells from senescence [44, 45]. Low levels of autophagy in cervical stromal cells under OS are suggestive of a mechanism forcing them to undergo senescence and not cell death. By contrast, we found low levels of senescence and high levels of autophagy in endocervical epithelial cells exposed to OS. The exposure of endocervical cells to OS may have caused severe cell damage, which cannot be salvaged by autophagy. Excessive autophagy in cells under stress can eventually lead to cell death [46]. Severe OS can also cause endocervical epithelial cell death via apoptosis and necrosis [47].

This study showed the different responses of cervical cells to OS, and this is reflective of their location and function. Ectocervical epithelial cells and cervical stromal cells are more resistant to OS as shown by a negligible decrease in cell viability, low apoptosis, and moderate levels of autophagy and necrosis, which is expected from a tissue undergoing remodeling throughout its existence. These cells can survive, promote inflammation, and undergo cellular remodeling. The ectocervical epithelial cells are constantly exposed to insults from the vaginal microbiota and attain heightened endogenous immune tolerance to prevent damage from insults, such as infection and OS [48], likely aided by the resident immune cells. This may have programmed these cells to withstand the pathologic effects of OS. On the other hand, the cervical stromal cells and endocervical epithelial cells are usually protected from the vaginal microbiota due to their location and their production of mucus which serve as physical barriers with antimicrobial peptides [49]. However, when these protective barriers are compromised, the pathologic effects of OS may be more detrimental to the cervical stromal and endocervical epithelial cells. Impairment in the barrier properties of cervical mucus could contribute to increased rates of intrauterine infection and preterm birth rates [50].

Our study showed that OS can also promote sterile endogenous inflammation and cell death in the cervix. The role of OS in women with cervical incompetence and short cervix is inconsistent [8, 13, 51]. However, we hypothesize that chronic inflammation and excessive cell death in the cervix from OS may cause tissue damage that may contribute to the development of cervical insufficiency and short cervix. Oxidative stress may damage the cervical epithelial barrier, especially the endocervix, and cause remodeling of the cervical stroma, which can compromise the mechanical properties of the cervix. This concept still needs to be validated through future in vivo and epidemiologic studies.

This study has several limitations. First, each cell type was analyzed separately, and therefore, intercellular interactions that can potentially produce specific intracellular changes in response to signals from other cells may not be reflected in our studies. An organ explant model or a microphysiologic model of entire cervix (organ on a chip) is needed to address these interactions. Second, this in vitro system lacked immune cells, which greatly contribute to the inflammatory response in the cervix. This study also lacks data on elemental damage, detailed analysis of signalers (except for the p38MAPK pathway), and a lack of mechanistic models. However, this is a solid descriptive study that generated several hypotheses and avenues for future research. Specifically, studies evaluating factors that trigger OS in the cervix are needed. In summary, this study highlights the potential role of OS in cellular remodeling of the cervix. OS promoted cell cycle arrest, different forms of cell death, and sterile inflammation that is likely mediated by p38MAPK activation in the cellular components of the cervix. Because pregnancy is associated with a general increase in OS, the pathologic effects of OS in the cervix may contribute to the normal and premature cervical ripening process, which can predispose patients to preterm birth.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Authors’ contributions

J.V. consented patients and collected tissue samples. O.A.G.T. conducted the experiments, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. R.M. conceived the project, designed experiments, and provided funding. R.M., P.M., and J.V. helped with data analysis and interpretation and prepared the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

† Grant Support: O. A. G. Tantengco is an MD–PhD trainee in the MD–PhD in Molecular Medicine Program, supported by the Philippine Council for Health Research and Development, Department of Science and Technology, Republic of the Philippines and administered through the University of the Philippines Manila. This study was supported partly by 5R21AI140249-01 (NIH/NIAID) to R. Menon.

Contributor Information

Ourlad Alzeus G Tantengco, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine and Perinatal Research, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, TX, USA; Biological Models Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines.

Joy Vink, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA.

Paul Mark B Medina, Biological Models Laboratory, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines.

Ramkumar Menon, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine and Perinatal Research, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, TX, USA.

References

- 1. Myers KM, Feltovich H, Mazza E, Vink J, Bajka M, Wapner RJ, Hall TJ, House M. The mechanical role of the cervix in pregnancy. J Biomech 2015; 48:1511–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, Mercer BM, Moawad A, Das Aet al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008; 371:75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crump C, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA. Gestational age at birth and mortality in young adulthood. JAMA 2011; 306:1233–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wen SW, Smith G, Yang Q, Walker M. Epidemiology of preterm birth and neonatal outcome. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2004; 9:429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vink J, Feltovich H. Cervical etiology of spontaneous preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2016; 21:106–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tantengco OAG, Menon R. Contractile function of the cervix plays a role in normal and pathological pregnancy and parturition. Med Hypotheses 2020; 45:110336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duhig K, Chappell LC, Shennan AH. Oxidative stress in pregnancy and reproduction. Obstet Med 2016; 9:113–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Menon R. Oxidative stress damage as a detrimental factor in preterm birth pathology. Front Immunol 2014; 5:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martin LF, Moço NP, Lima MD, Polettini J, Miot HA, Corrêa CRet al. Histologic chorioamnionitis does not modulate the oxidative stress and antioxidant status in pregnancies complicated by spontaneous preterm delivery. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017; 17:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dutta EH, Behnia F, Boldogh I, Saade GR, Taylor BD, Kacerovský Met al. Oxidative stress damage-associated molecular signaling pathways differentiate spontaneous preterm birth and preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Mol Hum Reprod 2015; 22:143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cinkaya A, Keskin HL, Buyukkagnici U, Gungor T, Keskin EA, Avsar AFet al. Maternal plasma total antioxidant status in preterm labor. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2010; 36:1185–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zolotukhin P, Aleksandrova A, Goncharova A, Shestopalov A, Rymashevskiy A, Shkurat T. Oxidative status shifts in uterine cervical incompetence patients. Syst Biol Reprod Med 2014; 60:98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sahlin L, Wang H, Stjernholm Y, Lundberg M, Ekman G, Holmgren Aet al. The expression of glutaredoxin is increased in the human cervix in term pregnancy and immediately post-partum, particularly after prostaglandin-induced delivery. Mol Hum Reprod 2000; 6:1147–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ryu HK, Moon JH, Heo HJ, Kim JW, Kim YH. Maternal c-reactive protein and oxidative stress markers as predictors of delivery latency in patients experiencing preterm premature rupture of membranes. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2017; 136:145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heng YJ, Di Quinzio MKW, Permezel M, Rice GE, Georgiou HM. Temporal expression of antioxidants in human cervicovaginal fluid associated with spontaneous labor. Antioxid Redox Signal 2010; 13:951–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khansari N, Shakiba Y, Mahmoudi M. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as a major cause of age-related diseases and cancer. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2009; 3:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lappas M, Hiden U, Desoye G, Froehlich J, Mouzon SH, De Jawerbaum A. The role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. Antioxid Redox Signal 2011; 15:3061–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hansson SR, Nääv Å, Erlandsson L. Oxidative stress in preeclampsia and the role of free fetal hemoglobin. Front Physiol 2015; 6:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manna P, Jain SK. Obesity, oxidative stress, adipose tissue dysfunction, and the associated health risks: causes and therapeutic strategies. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2015; 13:423–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raijmakers MTM, Dechend R, Poston L. Oxidative stress and preeclampsia: rationale for antioxidant clinical trials. Hypertension 2004; 44:374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Butcher LD, Hartog G, Ernst PB, Crowe SE. Oxidative stress resulting from helicobacter pylori infection contributes to gastric carcinogenesis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 3:316–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Herbst-Kralovetz MM, Quayle AJ, Ficarra M, Greene S, Rose WA, Chesson Ret al. Quantification and comparison of toll-like receptor expression and responsiveness in primary and immortalized human female lower genital tract epithelia. Am J Reprod Immunol 2008; 59:212–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tantengco OAG, Richardson LS, Menon R. Effects of a gestational level of estradiol on cellular transition, migration, and inflammation in cervical epithelial and stromal cells. Am J Reprod Immunol 2020. doi: 10.1111/aji.13370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Richardson LS, Taylor RN, Menon R. Reversible EMT and MET mediate amnion remodeling during pregnancy and labor. Sci Signal 2020; 13:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jin J, Richardson L, Sheller-Miller S, Zhong N, Menon R. Oxidative stress induces p38MAPK-dependent senescence in the feto-maternal interface cells. Placenta 2018; 67:15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dixon CL, Richardson L, Sheller-Miller S, Saade G, Menon R. A distinct mechanism of senescence activation in amnion epithelial cells by infection, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Am J Reprod Immunol 2018; 79:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Richardson L, Dixon CL, Aguilera-Aguirre L, Menon R. Oxidative stress-induced TGF-beta/TAB1-mediated p38MAPK activation in human amnion epithelial cells. Biol Reprod 2018; 99:1100–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoshii SR, Mizushima N. Monitoring and measuring autophagy. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lavu N, Richardson L, Radnaa E, Kechichian T, Urrabaz-Garza R, Sheller-Miller Set al. Oxidative stress-induced downregulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta in fetal membranes promotes cellular senescence. Biol Reprod 2019; 101:1018–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lavu N, Sheller-Miller S, Kechichian T, Cayenne S, Bonney EA, Menon R. Changes in mediators of pro-cell growth, senescence, and inflammation during murine gestation. Am J Reprod Immunol 2020; 83:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nikoletopoulou V, Markaki M, Palikaras K, Tavernarakis N. Crosstalk between apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta-Mol Cell Res 2013; 1833:3448–3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fialová L, Malbohan I, Kalousová M, Soukupová J, Krofta L, Štípek Set al. Oxidative stress and inflammation in pregnancy. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2006; 66:121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Polettini J, Richardson LS, Menon R. Oxidative stress induces senescence and sterile inflammation in murine amniotic cavity. Placenta 2018; 63:26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sultana Z, Maiti K, Aitken J, Morris J, Dedman L, Smith R. Oxidative stress, placental ageing-related pathologies and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Reprod Immunol 2017; 77:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Allaire AD, D’Andrea N, Truong P, McMahon MJ, Lessey BA. Cervical stroma apoptosis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2001; 97:399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Díaz-Castro J, Florido J, Kajarabille N, Prados S, De Paco C, Ocon Oet al. A new approach to oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling during labour in healthy mothers and neonates. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015;178536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cha JM, Aronoff DM. A role for cellular senescence in birth timing. Cell Cycle 2017; 16:2023–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Menon R, Mesiano S, Taylor RN. Programmed fetal membrane senescence and exosome-mediated signaling: a mechanism associated with timing of human parturition. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017; 8:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Velarde MC, Menon R. Positive and negative effects of cellular senescence during female reproductive aging and pregnancy. J Endocrinol 2016; 230:R59–R76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cox LS, Redman C. The role of cellular senescence in ageing of the placenta. Placenta 2017; 52:139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hadley EE, Sheller-Miller S, Saade G, Salomon C, Mesiano S, Taylor RNet al. Amnion epithelial cell–derived exosomes induce inflammatory changes in uterine cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018; 219:478.e1–478.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Filomeni G, De Zio D, Cecconi F. Oxidative stress and autophagy: the clash between damage and metabolic needs. Cell Death Differ 2015; 22:377–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Patel NH, Sohal SS, Manjili MH, Harrell JC, Gewirtz DA. The roles of autophagy and senescence in the tumor cell response to radiation. Radiat Res 2020; 194:103–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wen X, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy is a key factor in maintaining the regenerative capacity of muscle stem cells by promoting quiescence and preventing senescence. Autophagy 2016; 12:617–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bialik S, Dasari SK, Kimchi A. Autophagy-dependent cell death—where, how and why a cell eats itself to death. J Cell Sci 2018;131:jcs215152. doi: 10.1242/jcs.215152. PMID: 30237248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen Y, McMillan-Ward E, Kong J, Israels SJ, Gibson SB. Oxidative stress induces autophagic cell death independent of apoptosis in transformed and cancer cells. Cell Death Differ 2008; 15:171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. De Tomasi JB, Opata MM, Mowa CN. Immunity in the cervix: interphase between immune and cervical epithelial cells. J Immunol Res 2019; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yarbrough VL, Winkle S, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Antimicrobial peptides in the female reproductive tract: a critical component of the mucosal immune barrier with physiological and clinical implications. Hum Reprod Update 2015; 21:353–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Critchfield AS, Yao G, Jaishankar A, Friedlander RS, Lieleg O, Doyle PSet al. Cervical mucus properties stratify risk for preterm birth. PLoS One 2013; 8:2–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Venkatesh KK, Cantonwine DE, Ferguson K, Arjona M, Meeker JD, McElrath TF. Inflammatory and oxidative stress markers associated with decreased cervical length in pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol 2016; 76:376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.