Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in significant changes to professional and personal lives of oncology professionals globally. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Resilience Task Force collaboration aimed to provide contemporaneous reports on the impact of COVID-19 on the lived experiences and well-being in oncology.

Methods

This online anonymous survey (July-August 2020) is the second of a series of global surveys launched during the course of the pandemic. Longitudinal key outcome measures including well-being/distress (expanded Well-being Index—9 items), burnout (1 item from expanded Well-being Index), and job performance since COVID-19 were tracked.

Results

A total of 942 participants from 99 countries were included for final analysis: 58% (n = 544) from Europe, 52% (n = 485) female, 43% (n = 409) ≤40 years old, and 36% (n = 343) of non-white ethnicity. In July/August 2020, 60% (n = 525) continued to report a change in professional duties compared with the pre-COVID-19 era. The proportion of participants at risk of poor well-being (33%, n = 310) and who reported feeling burnout (49%, n = 460) had increased significantly compared with April/May 2020 (25% and 38%, respectively; P < 0.001), despite improved job performance since COVID-19 (34% versus 51%; P < 0.001). Of those who had been tested for COVID-19, 8% (n = 39/484) tested positive; 18% (n = 7/39) felt they had not been given adequate time to recover before return to work. Since the pandemic, 39% (n = 353/908) had expressed concerns that COVID-19 would have a negative impact on their career development or training and 40% (n = 366/917) felt that their job security had been compromised. More than two-thirds (n = 608/879) revealed that COVID-19 has changed their outlook on their work-personal life balance.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact the well-being of oncology professionals globally, with significantly more in distress and feeling burnout compared with the first wave. Collective efforts from both national and international communities addressing support and coping strategies will be crucial as we recover from the COVID-19 crisis. In particular, an action plan should also be devised to tackle concerns raised regarding the negative impact of COVID-19 on career development, training, and job security.

Key words: well-being, burnout, job performance, oncology professionals, resilience, COVID-19

Highlights

-

•

Compared with survey I, more oncology professionals were at risk of poor well-being (33% versus 25%) and burnout (49% versus 38%).

-

•

Job performance since COVID-19 (JP-CV) has improved from 34% to 51%.

-

•

About 1 in 5 who tested positive for COVID-19 felt they had not been given adequate time to recover before return to work.

-

•

Some 39% expressed concerns that COVID-19 would have a negative impact on their career development or training.

-

•

More than two-thirds revealed that COVID-19 had changed their outlook on work-personal life balance.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and our response to it continues to shape lives globally. Many health care workers have seen both their professional and personal lives significantly impacted, with the oncology community being no exception. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Resilience Task Force, established in December 2019, launched a longitudinal series of global surveys in April/May 2020 (survey I) and July/August 2020 (survey II) to evaluate the challenges posed by COVID-19 on the daily practice and well-being of oncology professionals.1 Preliminary results from our survey series indicate that COVID-19 has had a significant impact on the oncology workforce. Of the 1520 survey I participants, 25% were at risk of distress, 38% reported feeling burnout, and 66% reported not being able to perform their job compared with the pre-COVID-19 era.1 A higher mortality rate from COVID-19 in individual countries correlated with poorer well-being. Individual psychological resilience and changes in work hours were also consistent predictors. This is in keeping with emerging trends in several studies reporting increased psychological distress and emotional exhaustion amongst health care workers, particularly with increased job demands, during this pandemic.2, 3, 4, 5 Concerningly, amongst the 272 participants who completed both surveys I and II, a significant increase in risk of distress/poor well-being (22% versus 31%) and burnout (35% versus 49%) was already noted over a 3-month period during the pandemic despite improvements in job performance.1

Here, we present the complete analysis of responses from all 942 participants of survey II of our global survey series.

Methods

Survey design

Survey II (open from 16 July 2020 to 5 August 2020) formed part of the series of online global surveys designed by the ESMO Resilience Task Force, in collaboration with ESMO Young Oncologists Committee, ESMO Women for Oncology Committee, ESMO Leaders Generation Programme Alumni members, and the OncoAlert Network. The programme of work, including this current survey, was approved by the ESMO Executive Board. Participants were invited predominantly through ESMO membership emails, and open access to the survey, hosted on the Qualtrics platform, was also available to both members and non-members through the ESMO website and social media channels. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

Survey measures

Key outcomes of interest including well-being, burnout, and job performance since COVID-19 (JP-CV) were longitudinally monitored as per survey I.1 In brief, a calculated cumulative score of ≥4 on the validated expanded Well-being Index (eWBI) 9-item screening tool is considered at risk of poor well-being or distress.6 A ‘yes’ response to the single item from eWBI,1,7 ‘have you felt burned out from your work?’ was used as a surrogate for self-reported burnout amongst participants. A JP-CV score of ≥3.5 was arbitrarily categorised as favourable JP-CV.1

In addition, psychological resilience [single-item 9-point bipolar scale, C. Hardy (unpublished data)], coping strategies, COVID-19-related job changes, perceptions of value and support, working environment, and changes to lifestyle were recorded. We also included contemporaneous questions relevant to participants’ experiences during this period of the pandemic, such as personal experience of COVID-19, perceptions of their career development and/or training and job security, and general outlook in life.

Statistical analysis

Key outcome variables including eWBI, burnout, JP-CV, and psychological resilience were longitudinally compared with the results from survey 11 to determine any changes over time. Descriptive data were presented as median (interquartile range) or mean ± standard deviation, and proportions were expressed as a percentage. Chi-square analysis was used to compare categorical variables and paired or unpaired t-tests were used to analyse continuous variables; P values were two-tailed and were considered significant if <0.05. Participants who completed ≥33% of the survey (completion of survey beyond personal demographic profile and with the four key outcome variables above recorded) were included in the final analysis. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS V.26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and data represented using GraphPad Prism V9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Participant demographics

A total of 942 participants from 99 countries who completed ≥33% of the online survey [n = 816 (86.6%) with 100% completion] were included in the final analysis. By July/August 2020, most participants (n = 826, 87.7%) had experienced some form of lockdown/restriction in their region of work and only a minority (n = 44, 4.7%) were working in a ‘COVID-19-free’ country. Table 1 summarises the key demographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (N = 942)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| ≤40 | 409 (43.4) |

| >40 | 533 (56.6) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 485 (51.5) |

| Male | 456 (48.4) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 587 (62.3) |

| Asian (East/Southeast) | 137 (14.5) |

| Asian (South) | 68 (7.2) |

| Hispanic | 67 (7.1) |

| Arab | 27 (2.9) |

| Mixed | 22 (2.3) |

| Black | 16 (1.7) |

| Other | 6 (0.6) |

| Prefer not to say | 12 (1.3) |

| Lives alone | |

| Yes | 167 (17.7) |

| No | 775 (82.3) |

| Have children | |

| Yes | 562 (59.7) |

| No | 380 (40.3) |

| Median number of children, n = 562 | 2 (range 1-8) |

| Age of children, n = 562 | |

| Pre-school | 151 (26.9) |

| Primary school | 181 (32.2) |

| Secondary school | 143 (25.4) |

| Adult (living at home) | 105 (18.7) |

| Adult (not living at home) | 148 (26.3) |

| Regiona | |

| Europeb | |

| Central Europe | 160 (17.0) |

| Southwestern Europe | 122 (13.0) |

| Northern Europe and British Isles | 93 (9.9) |

| Southeastern Europe | 89 (9.4) |

| Western Europe | 49 (5.2) |

| Eastern Europe | 31 (3.3) |

| Asia | 192 (20.4) |

| North America | 74 (7.9) |

| South America | 69 (7.3) |

| Africa | 38 (4.0) |

| Oceania | 23 (2.4) |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (0.2) |

| Primary place of work | |

| General hospital | 421 (44.1) |

| Cancer centre | 368 (39.1) |

| Private outpatient clinic | 70 (7.4) |

| Pharmaceutical/technology company | 18 (1.9) |

| Health care organisation | 14 (1.5) |

| Other | 51 (5.4) |

| Specialtyc | |

| Medical oncology | 634 (67.3) |

| Clinical oncology | 178 (18.9) |

| Haemato-oncology | 102 (10.8) |

| Palliative care | 61 (6.5) |

| Radiation oncology | 53 (5.6) |

| Laboratory-based researcher/scientist | 33 (3.5) |

| Surgical oncology | 26 (2.8) |

| Nursing | 11 (1.2) |

| Other | 60 (6.4) |

| Trainee | |

| Yes | 184 (19.5) |

| No | 758 (80.5) |

| Duration of training completed (years), n = 184 | |

| <2 | 36 (19.6) |

| 2-5 | 103 (56.0) |

| >5 | 45 (24.4) |

| Post-training oncology experience (years), n = 758 | |

| <5 | 152 (20.0) |

| 5-10 | 165 (21.8) |

| >10 | 437 (57.7) |

| Not applicable | 4 (0.5) |

| ESMO member | |

| Yes | 854 (90.7) |

| No | 88 (9.3) |

ESMO, European Society for Medical Oncology.

Countries most represented were Germany (n = 85), India (n = 67), UK (n = 62), Italy (n = 56), Spain, (n = 44) and Brazil (n = 34).

Central Europe—Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Switzerland; Southwestern Europe—Italy, Portugal, Spain; Northern Europe and the British Isles—Denmark, Finland, Norway, Republic of Ireland, Sweden, UK; Southeastern Europe—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Israel, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey; Western Europe—Belgium, France, Luxembourg, The Netherlands; and Eastern Europe—Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Russian Federation, Ukraine.

Note that some participants have selected two or more specialties within their job role, and proportion of representation is summarised as such.

During the time of survey II, responses were predominantly from Europe (n = 544, 57.7%) with the highest representation from those working in medical oncology (n = 634, 67.3%) and those working in a general hospital (n = 421, 44.1%) or tertiary cancer centre (n = 368, 39.1%) (Table 1). More than half of the participants were female (n = 485, 51.5%), >40 years old (n = 533, 56.6%), and of white ethnicity (n = 587, 62.3%) (Table 1). About 1 in 5 (n = 184) were trainees, and amongst those who were fully trained oncologists, a majority (n = 437, 57.7%) had >10 years of experience in the field (Table 1).

Changes in professional duties since COVID-19

In July/August 2020, a majority of participants (n = 525/869, 60.4%) were still reporting a change in their professional duties when compared with the pre-COVID-19 era. The nature of changes in professional duties is outlined in Table 2. There was a marked increase in remote consultations (n = 472/528, 89.4%), virtual multidisciplinary team/tumour board meetings (n = 450/534, 84.3%), remote meetings (n = 506/550, 92.0%), and COVID-19-related research activity (n = 202/344, 58.7%) (Table 2). In particular, more than a third (n = 221/575, 38.4%) had reported an increase in overall hours of work in comparison to pre-COVID-19 work schedule and about two-thirds (n = 362/549, 65.9%) had reported an increase in hours working from home (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100199). The majority were still experiencing a reduction in clinical trials (n = 320/486, 65.8%) and other research (n = 275/493, 55.8%) activities (Table 2). Overall, however, the self-reported JP-CV had increased compared with April/May 2020; the proportion of those with JP-CV score ≥3.5 had increased from 34.4% (n = 523/1520) to 50.9% (n = 444/873) in July/August 2020, P < 0.001.

Table 2.

Overview of the changes in professional duties since the COVID-19 outbreak (N = 942)

| n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in professional duties | ||||

| Yes | 525 (60) | |||

| No | 344 (40) | |||

| Work routine has returned to pre-COVID-19 situation | Disagree 441 (51) |

Neither 148 (17) |

Agree 280 (32) |

|

| Nature of change in duties, n = 579 | ||||

| Scope of clinical work | Increased | No change | Decreased | N/A |

| Direct patient care | 135 (26) | 200 (38) | 190 (36) | 54 |

| Remote consultations | 472 (89) | 40 (8) | 16 (3) | 51 |

| Inpatient work | 111 (22) | 205 (41) | 179 (36) | 84 |

| COVID-19 inpatient work | 137 (40) | 164 (48) | 39 (12) | 239 |

| Covering other oncology patients | 132 (31) | 230 (54) | 64 (15) | 153 |

| Covering non-oncology specialties | 120 (32) | 226 (59) | 34 (9) | 199 |

| Virtual MDT/tumour board meetings | 450 (84) | 59 (11) | 25 (5) | 45 |

| Remote meetings | 506 (92) | 29 (5) | 15 (3) | 29 |

| Working hours and shift patterns | Increased | No change | Decreased | N/A |

| Overall hours of work | 221 (38) | 198 (34) | 156 (27) | 4 |

| Out-of-hours work in hospital | 183 (36) | 197 (39) | 128 (25) | 71 |

| Hours working from home | 362 (66) | 156 (28) | 31 (6) | 30 |

| Weekend shifts | 87 (19) | 295 (65) | 72 (16) | 125 |

| Overnight shifts | 61 (15) | 277 (70) | 57 (14) | 184 |

| Clinical trial and research activity | Increased | No change | Decreased | N/A |

| Clinical trial activity | 34 (7) | 132 (27) | 320 (66) | 93 |

| Research (non-clinical trials) activity | 79 (16) | 139 (28) | 275 (56) | 86 |

| COVID-19 related research | 202 (59) | 120 (35) | 22 (6) | 235 |

| Redeployed | ||||

| Yes | 45 (5.2) | |||

| Partially | 140 (16.0) | |||

| No | 687 (78.8) | |||

| Duration of redeployment, n = 185 | ||||

| <4 weeks | 61 (33.0) | |||

| 1-3 months | 77 (41.6) | |||

| >3 months | 44 (23.8) | |||

| Prefer not to say | 3 (1.6) | |||

MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Personal experience of COVID-19

More than 1 in 5 participants (n = 181/854, 21.2%) disclosed that their current circumstances or underlying comorbidities would put them at an increased personal risk of being seriously ill from COVID-19 (Table 3). Amongst those who had been tested (n = 484), 39 participants (8.1%) had had COVID-19. Most underwent isolation or sick leave due to COVID-19 symptoms (n = 25/39, 64.1%). Within this subgroup who had had COVID-19, the median duration of symptomatic COVID-19 was 8.5 days (n = 22, range 1 to 42 days). About 1 in 5 (n = 7/39) did not feel they were given appropriate time to recover and 11 participants (28.2%) did not feel completely recovered upon return to work. Notably, 14.8% (n = 126/849) revealed that they have had a colleague who has died from COVID-19.

Table 3.

Participants’ personal experience of COVID-19 (N = 854)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Increased personal risk due to comorbidities or condition | |

| Yes | 181 (21.2) |

| No | 648 (75.9) |

| Prefer not to say | 25 (2.9) |

| Characteristics of comorbidities or condition | |

| Cardiac | 53 (6.2) |

| Respiratory | 45 (5.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 28 (3.3) |

| Immunosuppressed | 20 (2.3) |

| Renal, hepatic, or neurological | 9 (1.1) |

| Pregnant | 6 (0.7) |

| Other | 65 (7.6) |

| Tested positive for COVID-19, n = 484 | |

| Yes | 39 (8.1) |

| No | 445 (91.9) |

| Isolation or sick leave due to COVID-19 symptoms, n = 39 | |

| <2 weeks | 5 (12.8) |

| 2-4 weeks | 17 (43.6) |

| >4 weeks | 3 (7.7) |

| No | 13 (33.3) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (2.6) |

| Hospitalised for COVID-19, n = 39 | |

| <2 weeks | 0 |

| 2-4 weeks | 1 (2.6) |

| >4 weeks | 0 |

| No | 37 (94.9) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (2.6) |

| Median duration of symptomatic COVID-19, n = 22 | 8.5 days (1-42) |

| Feel given appropriate time to recover, n = 39 | |

| Yes | 28 (71.8) |

| No | 7 (17.9) |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (10.3) |

| Feel completely recovered upon return to work, n = 39 | |

| Yes | 25 (64.1) |

| No | 11 (28.2) |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (7.7) |

| Had colleague who has died from COVID-19, n = 849 | |

| Yes | 126 (14.8) |

| No | 713 (84.0) |

| Prefer not to say | 10 (1.2) |

The impact of COVID-19 on perception of career development and training

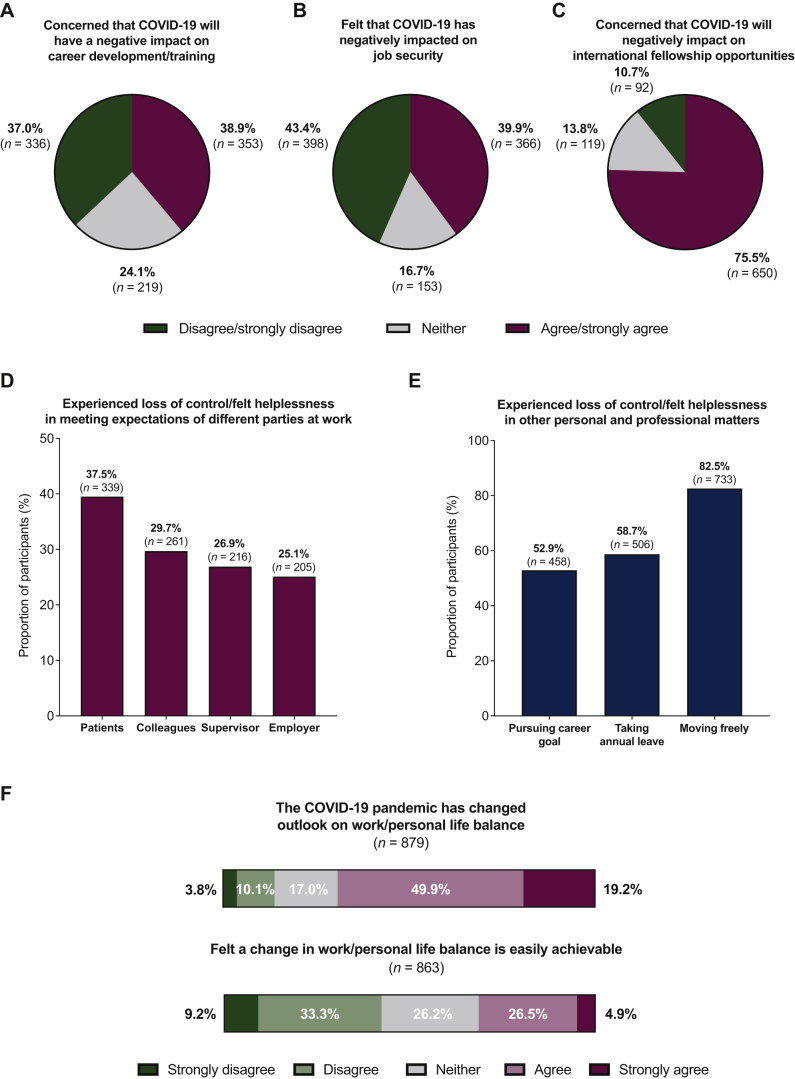

As the COVID-19 pandemic evolved, we questioned participants regarding their outlook in their personal and professional life. Alarmingly, 38.9% (n = 353/908) had expressed concerns that the pandemic would have a negative impact on their career development and/or training, and 39.9% (n = 366/917) felt that COVID-19 has negatively impacted on their job security (Figure 1A and B). A majority (n = 650/861, 75.5%) were also concerned about the negative impact on international fellowship opportunities (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

The impact of COVID-19 on (A-C) the perception of career development and/or training opportunities (n = 925), (D-E) sense of control (n = 892), and (F) future outlook in work/personal life balance (n = 892).

The feeling of loss of control and helplessness during the COVID-19 crisis

During the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than a third of participants (n = 339/859, 37.5%) had experienced a loss of control or felt helpless in meeting the expectations of their patients (Figure 1D). Similarly, more than a quarter also expressed the perception of loss of control or helplessness in meeting the expectations of their colleagues, supervisor, and/or employer (Figure 1D). Additionally, more than half felt a loss of control or helpless with regards to pursuing their career goal (n = 458/866, 52.9%) (Figure 1E).

On personal reflection, for more than two-thirds of participants (n = 608/879, 69.2%), the COVID-19 pandemic had changed their outlook on work-personal life balance (Figure 1F). A majority (n = 612/870, 70.3%) would like to dedicate more time to their personal life, however only less than a third (n = 271/863, 31.4%) felt that a change in their work-personal life balance could be easily achievable (Figure 1F). Currently, 43.0% (n = 405/942) of participants did not feel that their work schedule leaves them enough time for their personal and family life.

Well-being and burnout

Among participants, 32.9% (n = 310) were at risk of poor well-being (eWBI score ≥4) and 48.8% (n = 460) reported feeling burnout compared with 25% (P < 0.001) and 38% (P < 0.001) of the 1520 participants surveyed in April/May 2020, respectively. The magnitude of increase in both of these outcome measures was also seen within the subgroup of 272 participants who responded to both surveys I and II.1

Resilience, well-being support, and coping strategies

Collectively, there was no difference in psychological resilience amongst participants in both surveys I and II: mean score 6.4 ± 1.9 versus 6.4 ± 2.0, respectively (P = 0.82). Access to well-being support services was available to less than half of the participants (n = 421, 44.7%). Supplementary Table 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100199 summarises a variety of well-being support services and coping strategies commonly used by participants during this COVID-19 pandemic. Importantly, a majority continued to feel well supported by their friends and/or family (n = 729/835, 87.3%) and by their colleagues at work (n = 648/835, 77.6%). In survey II, 63.9% (n = 537/841) and 53.7% (n = 452/841) expressed feeling valued by the public and their work organisation, respectively.

Discussion

Within a 3-month period (April/May 2020 to July/August 2020) at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, survey II has already highlighted a significant increase in risk of poor well-being (33% versus 25%) and burnout (49% versus 38%). This is despite significant improvement in self-reported job performance over the same time period. This is an alarming finding and suggests that, although oncology professionals may be adapting effectively to change, they continue to be at increasing risk of distress.

Survey II highlights a number of factors in the current climate that may be contributing to this deterioration in well-being. Most participants (n = 826, 88%) had experienced some form of lockdown/restriction in their region of work. In addition to such significant imposed changes in their personal lives, around 60% of participants continued to report a change in professional duties. Some of these, such as an increase in remote consultations and virtual meetings, have their advantages.4,8 However, nearly 40% had reported an overall increase in their work hours compared with their pre-COVID-19 schedule (also see Supplementary Figure S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100199). The majority had also experienced a reduction in clinical trials and traditional oncology-focused research activity. These are an integral part of working life in oncology and often a source of meaning. Increased working hours and a reduction in activities that are professionally meaningful are well-known risk factors for burnout.9

More survey II participants had reported a close personal experience with COVID-19 either by testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 (8%) or requiring self-isolation or sick leave due to COVID-19 symptoms (18%). Worryingly, nearly 15% had had a colleague die of COVID-19. Furthermore, one in five participants also disclosed that they had underlying comorbidities that would put them at an increased personal risk of being seriously ill from COVID-19. Of those who have had COVID-19, the median duration of symptomatic COVID-19 was 8.5 days but notably, the range for this was broad, from 1 to 42 days. Importantly, 18% feel that they did not have enough time to recover from illness and close to 30% did not feel completely recovered from illness before returning to work. Given the reports of potential substantial long-term morbidity associated with COVID-19 (‘long COVID’),10,11 this is a particular cause for concern and will require careful ongoing monitoring.

A substantial number of participants had expressed significant uncertainty about the future of their professional lives. Approximately 40% felt that COVID-19 would have a negative impact on their career development, training, and job security. More than 75% were also concerned about the negative impact on international fellowship opportunities, an important facet of professional development in oncology. This ties in with a recurrent concern expressed by participants of a loss of control or helplessness in achieving their career goals (53%).

Anxiety and fear amongst health care workers can be associated with higher rates of burnout.4 Delays in patient care and treatment have been a substantial source of distress in other studies for oncology practitioners.4 These are understandable responses in a climate of crisis and prolonged uncertainty as has been noted during previous pandemics.3 Overall, our findings highlight significantly increasing rates of distress and burnout. The rapidity in the rates of increased burnout distress within a 3-month period is a notable finding and a major cause for concern. This may be an ominous harbinger of what lies ahead in ongoing and future ESMO Resilience Task Force surveys which have coincided with periods of extended lockdown and further ‘waves’ of cases and deaths. The time for action therefore is now. Survey II already highlights useful areas of support and immediate intervention that may be of benefit to oncology professionals globally.

Firstly, there are significant measures organisations can take to improve the well-being of staff. Enhanced mentorship of practitioners to ensure ongoing support for career development and planning as well as sourcing of suitable professional opportunities. Despite the focus on the COVID-19 response, ongoing investment in oncology-focused research and clinical trials needs to continue, including fostering transnational fellowship opportunities.12, 13, 14 More particularly, despite additional pressures, the accessible and continued support of supervisors for trainees is even more paramount. A routinely scheduled time for a ‘team huddle’ or debriefing program for all staff in the emergency department has been shown to be well received and beneficial for both junior and senior team members alike during these challenging times.15

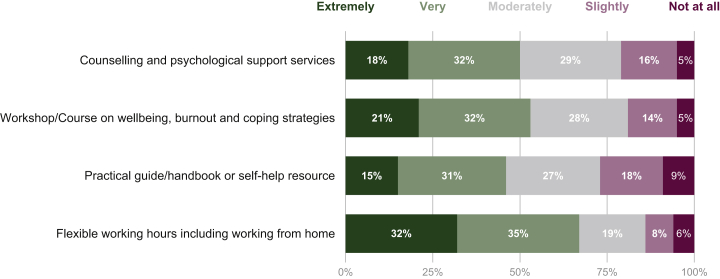

Secondly, the personal impact of COVID-19 on the health and well-being of oncology professionals has been emphasised by the findings of survey II. Ensuring safe work conditions, including access to personal protective equipment, COVID-19 testing, and vaccination are paramount (also see Supplementary Figure S2, available at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100199).16,17 Also, ensuring the provision of adequate sick leave for self-isolation and recovery from symptoms should be mandated, as well as, supporting ‘shielding’ practices to ensure those with comorbidities are in lower risk activities or exposure sites. The number of participants who had experienced the death of a colleague also raises the need for adequate access to bereavement support. Participants had similarly highlighted that access to counselling/psychological services and other resources to promote well-being and coping strategies would be welcomed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of key suggestions from participants on well-being and coping strategies which might be helpful as part of the COVID-19 recovery plan (n = 827).

Of importance for future oncology workforce planning, the majority of participants had reported changing their outlook on their work-personal life balance as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, including a desire for better work-life balance. The majority supported flexible working hours, including working from home. Ensuring work hours and workplace flexibility, as well as encouraging staff to take annual leave are important organisational leadership measures.

Although we focus on the solutions necessary, participants had likewise shared a number of strategies they were already using to cope currently, such as tapping into personal and professional support networks, employing strategies such as mindfulness meditation and smartphone apps, and feeling valued by their organisation. Supportive interventions need to be multifaceted with workplaces, and national and international oncology societies such as ESMO and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)18 playing a key facilitative role.

A significant strength of survey II is our substantial participant size of 942 and scope with 99 countries being represented. More than a third of our participants were from Germany, India, UK, Italy, Spain, and Brazil—a number of these countries have borne the brunt of global morbidity and mortality, which makes their representation in this survey important and notable. There was even representation across the genders (52% female), as well as young oncologists (43%), current trainees (20%), and those of non-white ethnicity (36%), as our previous research and that of other groups have found these groups to be at particularly heightened risk of experiencing burnout.1,19,20 More than a third of participants were of non-white ethnicity, which is again an important aspect as studies have shown that those of black or minority ethnic backgrounds are at higher risk of complications from COVID-19.21

A key factor in the well-being of all during these times has been the response of individual nations to this pandemic. Only a small minority of participants in our survey (4%) were from ‘COVID-19-free’ nations, which reflects their smaller population size. Our ability to discern the difference in well-being between those in higher prevalence versus COVID-19-free regions has been limited by this small sample size. This is also a cross-sectional, observational study which limits our ability to infer causality. However, to our knowledge, this is the only survey series in oncology addressing well-being systematically and longitudinally throughout the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. A substantially larger dataset from the recently closed survey III and more detailed longitudinal statistical analyses of factors associated with well-being, burnout, and distress will provide further insight into navigating recovery plans going forwards. The collective experience shared by participants completing this survey series, and the ongoing work of the ESMO Resilience Task Force and other organisations will help direct efforts to support the well-being of oncology professionals globally.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for taking part, and national societies and organizations who helped distribute the survey. We also thank Francesca Longo, Mariya Lemosle, and Katharine Fumasoli from the ESMO Head Office for providing vital administrative support for the delivery of this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) (no grant number): for license to use Qualtrics (online survey platform), and publication of figure fee.

Disclosure

KHJL is currently funded by the Wellcome-Imperial 4i Clinical Research Fellowship, and reports speaker honorarium from Janssen, outside the submitted work. KP’s institution received speaker fees or honoraria for consultancy/advisory roles from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Medscape, Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Hoffmann La Roche, Mundipharma, PharmaMar, Teva, Vifor Pharma; KP’s institution received a research grant from Sanofi; KP received travel support from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar and Roche; all outside the submitted work. CO reports research funding and honoraria from Roche; travel grant and honoraria from Medac Pharma and Ipsen Pharma; and travel grant from PharmaMar; outside the submitted work. TA reports personal fees from Pierre Fabre and CeCaVa; personal fees and travel grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS); grants, personal fees, and travel grants from Novartis; and grants from Neracare, Sanofi, and SkylineDx; all outside the submitted work. PG reports personal fees from Roche, MSD, BMS, Boerhinger-Ingelheim, Pfizer, AbbVie, Novartis, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Blueprint Medicines, Takeda, Gilead, and ROVI, outside the submitted work. ML acted as a consultant for Roche, AstraZeneca, Lilly, and Novartis, and received honoraria from Theramex, Roche, Novartis, Takeda, Pfizer, Sandoz, and Lilly, outside the submitted work. CBW reports speaker honoraria, travel support, and advisory board: Bayer, BMS, Celgene, Roche, Servier, Shire/Baxalta, RedHil, and Taiho; speaker honoraria from Ipsen; and advisory board in GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Sirtex, and Rafael; outside the submitted work. JBAGH reports personal fees for advisory role in Neogene Tx; grants and fees paid to institution from BMS, MSD, Novartis, BioNTech, Amgen; and fees paid to institution from Achilles Tx, GSK, Immunocore, Ipsen, Merck Serono, Molecular Partners, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics, Third Rock Ventures, Vaximm; outside the submitted work. CH reports being Director of a private company Hardy People Ltd., outside the submitted work. SB reports research grant (institution) from AstraZeneca, Tesaro, and GSK; honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, MSD, GSK, Clovis, Genmab, Merck Serono, Mersana, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, and Tesaro; outside the submitted work. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Banerjee S., Lim K.H.J., Murali K. The impact of COVID-19 on oncology professionals: results of the ESMO Resilience Task Force survey collaboration. ESMO Open. 2021;6(2):100058. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng K.Y.Y., Zhou S., Tan S.H. Understanding the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with cancer, their caregivers, and health care workers in Singapore. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1494–1509. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barello S., Caruso R., Palamenghi L. Factors associated with emotional exhaustion in healthcare professionals involved in the COVID-19 pandemic: an application of the job demands-resources model. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00420-021-01669-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao K.A., Attai D., Bleicher R. Covid-19 related oncologist's concerns about breast cancer treatment delays and physician well-being (the CROWN study) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;186(3):625–635. doi: 10.1007/s10549-021-06101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marton G., Vergani L., Mazzocco K., Garassino M.C., Pravettoni G. 2020s Heroes are not fearless: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on wellbeing and emotions of Italian health care workers during Italy phase 1. Front Psychol. 2020;11:588762. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.588762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyrbye L.N., Satele D., Shanafelt T. Ability of a 9-item well-being index to identify distress and stratify quality of life in US workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(8):810–817. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyrbye L.N., Satele D., Sloan J., Shanafelt T.D. Utility of a brief screening tool to identify physicians in distress. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):421–427. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman K.E., Garner D., Koong A.C., Woodward W.A. Understanding the intersection of working from home and burnout to optimize post-COVID19 work arrangements in radiation oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;108(2):370–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murali K., Makker V., Lynch J., Banerjee S. From burnout to resilience: an update for oncologists. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:862–872. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_201023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkatesan P. NICE guideline on long COVID. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(2):129. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00031-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah W., Hillman T., Playford E.D., Hishmeh L. Managing the long term effects of Covid-19: summary of NICE, SIGN, and RCGP rapid guideline. Br Med J. 2021;372:n136. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakouny Z., Hawley J.E., Choueiri T.K. COVID-19 and cancer: current challenges and perspectives. Cancer Cell. 2020;38(5):629–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan G., Lambertini M., Kourie H.R. Career opportunities and benefits for young oncologists in the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) ESMO Open. 2016;1(6):e000107. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan G., de Azambuja E., Punie K. OncoAlert round table discussions: the global COVID-19 experience. JCO Glob Oncol. 2021;7:455–463. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azizoddin D.R., Vella Gray K., Dundin A., Szyld D. Bolstering clinician resilience through an interprofessional, web-based nightly debriefing program for emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(5):711–715. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1813697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curigliano G., Banerjee S., Cervantes A. Managing cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: an ESMO multidisciplinary expert consensus. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(10):1320–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garassino M.C., Vyas M., de Vries E.G.E. The ESMO Call to Action on COVID-19 vaccinations and patients with cancer: vaccinate. Monitor. Educate. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(5):579–581. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hlubocky F.J., Symington B.E., McFarland D.C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on oncologist burnout, emotional well-being, and moral distress: considerations for the cancer organization's response for readiness, mitigation, and resilience. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021:OP2000937. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banerjee S., Califano R., Corral J. Professional burnout in European young oncologists: results of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Young Oncologists Committee Burnout Survey. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(7):1590–1596. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torrente M., Sousa P.A., Sanchez-Ramos A. To burn-out or not to burn-out: a cross-sectional study in healthcare professionals in Spain during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e044945. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sze S., Pan D., Nevill C.R. Ethnicity and clinical outcomes in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29:100630. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.