Abstract

The most severe cases of COVID-19, and the highest rates of death, are among the elderly. There is an urgent need to search for an agent to treat the disease and control its progression. Boswellia serrata is traditionally used to treat chronic inflammatory diseases of the lung. This review aims to highlight currently published research that has shown evidence of potential therapeutic effects of boswellic acids (BA) and B. serrata extract against COVID-19 and associated conditions. We reviewed the published information up to March 2021. Studies were collected through a search of online electronic databases (academic libraries such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Egyptian Knowledge Bank). Several recent studies reported that BAs and B. serrata extract are safe agents and have multiple beneficial activities in treating similar symptoms experienced by patients with COVID-19. Because of the low oral bioavailability and improvement of buccal/oral cavity hygiene, traditional use by chewing B. serrata gum may be more beneficial than oral use. It is the cheapest option for a lot of poorer people. The promising effect of B. serrata and BA can be attributed to its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, cardioprotective, anti-platelet aggregation, antibacterial, antifungal, and broad antiviral activity. B. serrata and BA act by multiple mechanisms. The most common mechanism may be through direct interaction with IκB kinases and inhibiting nuclear factor-κB-regulated gene expression. However, the most recent mechanism proposed that BA not only inhibited the formation of classical 5-lipoxygenase products but also produced anti-inflammatory LOX-isoform-selective modulators. In conclusion a small to moderate dose B. serrata extract may be useful in the enhancing adaptive immune response in mild to moderate symptoms of COVID-19. However, large doses of BA may be beneficial in suppressing uncontrolled activation of the innate immune response. More clinical results are required to determine with certainty whether there is sufficient evidence of the benefits against COVID-19.

Keywords: Boswellic acids/Boswelliaserrata, Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, Antiviral immunomodulator, COVID-19

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a kind of viral pneumonia caused by the novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The emerging COVID-19 pandemic has caused a major global health threat. Also, it has caused a lot of economic damage to most countries of the world (Rothan and Byrareddy 2020). Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in severe cases is the main cause of death associated with COVID-19. The deadly uncontrolled systemic inflammatory response results from the release of large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The cytokine storm triggers a violent attack by the immune system on the body, causing ARDS and multiple organ failure, and finally leading to death in severe cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Xu et al. 2020; Huang et al. 2020).

The elderly are more likely to get ARDS, so the most severe cases of COVID-19, and the highest rates of death, are among the elderly. However, the elderly are more likely to die from other causes, and the virus is more likely to affect the heart in the elderly, so it has been shown that people with COVID-19 die from heart attacks or stress on the body in general (Yanez et al. 2020; Lloyd-Sherlock et al. 2020). The impaired immune response in older individuals, i.e., immunosenescence and inflammaging play a major role in contributing to the significantly higher mortality rates seen in the elderly (Chen et al. 2021). Immunosenescence and inflammaging are key features of the aging immune system as the accumulation of senescent immune cells contributes to its degradation and, at the same time, an increase in inflammatory phenotypes leads to immune dysfunction (Bajaj et al. 2021). It has been suggested that senotherapeutic agents can reduce RNA virus replication in senescent cells and may have potential therapeutic activity against COVID-19 (Malavolta et al. 2020).

Older adults are less able to respond to new antigens because of the decreased frequency of naive T cells. They cannot frequently clear the virus through an efficient adaptive immune response as in young people. Indeed, antibody-secreting cells and follicular helper T cells are thought to be less effective than in young patients (Kadambari et al. 2020). As a result of failure to elicit an effective adaptive immune response, the elderly are more likely to have the uncontrolled activation of the innate immune response that leads to cytokine release syndrome and tissue damage (Cunha et al. 2020).

Currently, there is no registered treatment for COVID-19; therefore, scientists are concerned with searching for a drug to treat this disease. The availability of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines to a large proportion of the population is, unfortunately, something that currently differs greatly between different countries. Furthermore, virus mutations may be a major problem in the effectiveness of the vaccines based on viral-encoded peptides. Many treatment regimens have been tried in the treatment of COVID-19; some show initial promise. On the basis of their antiviral effect against COVID-19 in vitro studies, the anti-rheumatoid chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin have received the most attention among antiviral treatments (Gao et al. 2020; Dong et al. 2020). However, the incidence of drug toxicity as QTc prolongation and retinal toxicity should be considered before the use of the drug (Fedson 2016; Singh et al. 2020).

More recently, many investigators have suggested that JAK inhibitors, typically used as anti-inflammatory and anti-rheumatoid arthritis agents, are a novel treatment strategy for COVID-19. Several clinical trials confirmed that baricitinib has a dual action, demonstrating its ability to block the entry of the virus into target cells and reduce markers of inflammation (Stebbing et al. 2021). It inhibits the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) signaling causing cytokine storm mediated by the JAK-STAT pathway in severe COVID-19 (Zhang et al. 2020; Wu and Yang 2020). Plasma levels of IL-6 have been reported to be a predictive indicator of mortality (Stebbing et al. 2020). Anti-inflammatory combination therapy of baricitinib and dexamethasone in severe COVID-19 was associated with greater improvement in lung function when compared to corticosteroids alone (Seif et al. 2020; Rodriguez-Garcia et al. 2021; Kim et al. 2021; Pum et al. 2021).

Several herbs have been identified as anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating agents that have been suggested to treat coronavirus (Editorial, Nature Plants 2020). It is reported that traditional Chinese medicine has been used in the control of infectious disease and many patients with SARS-CoV infection have benefited from these herbal treatments (Yang et al. 2020; Luo et al. 2020).

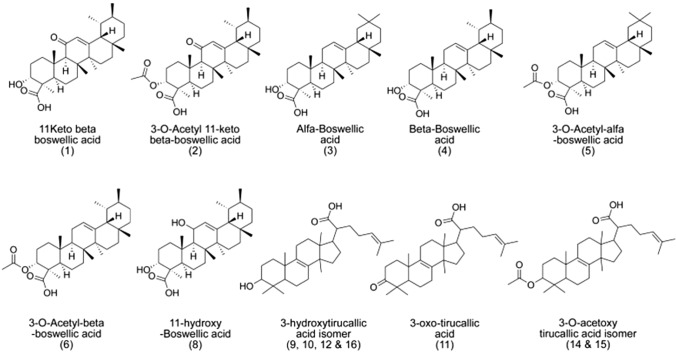

Gum resin extract of Boswellia serrata (B. serrata) has been used for centuries to treat a wide range of inflammatory diseases such as arthritis, diabetes, asthma, cancer, or inflammatory bowel (Roy et al. 2019). Zang et al. (2019) confirmed that the anti-inflammatory effect of B. serrata could be a potential therapy for the treatment of several inflammatory diseases. Phytochemical examination by thin-layer chromatography showed the main components present in the gum resin of B. serrata included terpenoids, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and phenylpropanoids (Ayub et al. 2018). More than 12 different boswellic acids have been identified as components of the B. serrata extract, but only KBA (11-keto-β-boswellic acid) and AKBA (3-O-acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid) have received marked pharmacological interest (Katragunta et al. 2019) (Fig. 1). The limited aqueous solubility and lipophilicity of these pentacyclic triterpenic acids decrease their bioavailability and pharmacological activity. The pharmaceutical development of KBA and AKBA has been extremely limited because of their low oral bioavailability (Sharma and Jana 2020). Other components such as phenolic compounds and flavonoids (quercetin, kaempferol) also play important roles in the anti-inflammatory actions of B. serrata (Gohel et al. 2018).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of boswellic acids (Katragunta et al. 2019)

This review aims to highlight currently published research that has shown evidence, based on the activity of B. serrata against pulmonary lesions, oxidative stress, inflammation, immune disturbance, viruses, and secondary microbial infection, for the potential therapeutic effects of boswellic acids (BA) and B. serrata extract against COVID-19 and the conditions associated with it.

Methods

We reviewed the published information up to March 2021. Studies were collected through a search of online electronic databases (academic libraries such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Egyptian Knowledge Bank).

Therapeutic basis of the potential use of BAs and B. serrata extract against SARS-CoV-2

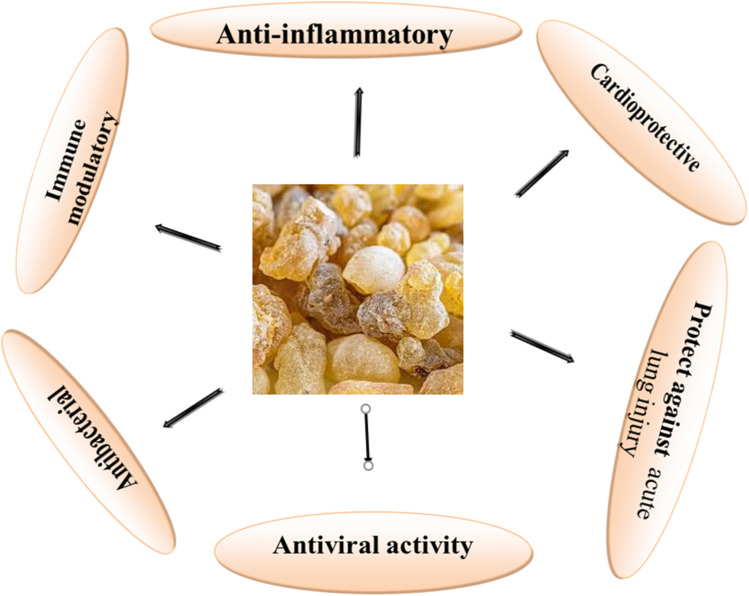

Based on scientific evidence, a recent publication suggested that some plant extracts or their components could have a role in the prevention and early treatment of symptoms of viral respiratory infections, and their rational management may also become a complementary treatment for patients with COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 (Firenzuoli et al. 2020). In B. serrata and in Glycyrrhiza glabra, several bioactive ingredients can reduce the production of ILs and leukotrienes. These medicinal plants are widely used in traditional Chinese medicine with some evidence of the effectiveness in the management of hepatitis B, HIV, SARS-CoV, and COVID-19 (Firenzuoli et al. 2020; Gomaa and Abdel-Wadood 2021). In our perspective review, we will discuss and evaluate the different effects of BAs and B. serrata extract that may be useful in combating SARS-CoV-2 and neutralizing any tissue-destructive effects of the virus (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Potential therapeutic effects of B. serrata gum, B. serrata extract, and boswellic acids in treating similar symptoms experienced by patients with COVID-19

Potential therapeutic effects of boswellic acids/B. serrata extract against SARS-CoV-2-induced pulmonary lesions

B. serrata has been traditionally used in folk medicine for centuries to treat coughs, asthma, and various chronic inflammatory diseases of the lung. It contains many active ingredients responsible for the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines, 5-lipoxygenase, and leukotriene production which is responsible for inflammation (Bosworth et al. 1983; Rashan et al. 2019). Boswellic acids and B. serrata extract have been demonstrated to suppress human leukocyte elastase (HLE), which may be involved in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis, chronic bronchitis, ARDS, and emphysema. HLE (a serine protease) is responsible for initiation of injury to the tissues and triggers the process of inflammation. HLE reduces the elasticity of the lungs and removal of mucus. It also constricts the lung passages and damages the secretion of mucus in the lungs. Boswellic acids and B. serrata extract have unique character owing to the dual inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase and HLE (Safayhi et al. 1997; Siddiqui 2011; Zhang et al. 2019; Roy et al. 2019). In a recent study, Gilbert et al. (2020) investigated the precise effect of B. serrata extract on the production of leukotienes, inflammatory mediators associated with asthma, by studying the structural changes and molecular mechanism of 5-lipoxygenase inhibition by AKBA. They observed that AKBA not only inhibited the formation of classical 5-lipoxygenase products but also caused a switch from the production of pro-inflammatory leukotrienes to the formation of anti-inflammatory LOX-isoform-selective modulators.

Moreover, B. serrata extract could combat bleomycin-induced injury, collagen accumulation, airway dysfunction, and pulmonary fibrosis in rats (Ali and Mansour 2011). Additionally, B. serrata extract showed a direct concentration-dependent relaxant effect on rat trachea precontracted with either ACh or KCl in vitro. These results may partly contribute to validating the traditional use of B. serrata in treating lung diseases (Hewedy 2020).

The anti-asthmatic activity of B. serrata was confirmed early, in a double-blind placebo controlled clinical study with 300 mg thrice daily dose for 6 weeks (Gupta et al. 1998). In other clinical studies by Houssen et al. (2010) and Al-Jawad et al. (2012) B. serrata extract was effective in the management of bronchial asthma owing to its natural anti-inflammatory and leukotriene inhibitory actions. It reduces the need for inhalation therapy with corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonists (Ferrara et al. 2015). Moreover, Liu et al. (2015) and Zhou et al. (2015) demonstrated that boswellic acid attenuates asthma phenotypes by downregulation of GATA3 via pSTAT6 inhibition. These results suggest that B. serrata might be effective in controlling the inflammation process in asthmatic conditions by inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory mediators (Rashan et al. 2019). A more recent study suggested that B. serrata ethanolic extracts possess significant anti-inflammatory activities in HL-60 cell lines and in BALB/c mice. This study is further support for use of B. serrata in the treatment of allergy, asthma, and other lung disorders (Soni et al. 2020). These therapeutic effects of B. serrata against induction of pulmonary lesions may be beneficial for the prevention of pulmonary lesions caused by COVID-19.

Potential therapeutic effects of boswellic acids/B. serrata extract against SARS-CoV-2-induced modification of cellular redox, inflammation, tissue injury, and severe hypercoagulability

There are a large number of findings in the literature showing the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of B. serrata and its phytochemicals. They have multiple modes of action, e.g., by inhibiting interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) mRNA expression, NF-B phosphorylation, synthesis of leukotriene and 5-lipoxygenase activity, and ameliorating oxidative stress (Miao et al. 2019; Efferth and Oesch 2020). Several investigations have suggested that boswellic acids and B. serrata extract can counteract free radicals that cause inflammation and thereby prevent tissue damage. It has been shown that B. serrata treatment alleviated oxidative stress and improved total antioxidant capacity in the liver, and reduced the expression of TNFα, NF-κB, TGFβ, IL-6, and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (Eltahir et al. 2020). On a histopathological level, B. serrata treatment also exhibited antifibrotic activity (Eltahir et al. 2020). The anti-inflammatory activity of B. serrata extracts on endothelial cells leads to a therapeutic application for cardiovascular and respiratory health (Bertocchi et al. 2018).

Several investigations indicate that the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects are not limited to one specific type of Boswellia (Efferth and Oesch 2020). Boswellia species showed 5-lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase (COX-1, 2) inhibitory activity (Siddiqui 2011). In addition, boswellic acids and other derivatives have been demonstrated to reduce the production of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, IFNγ, and TNFα that are ultimately directed to tissue destruction such as lung, cartilage, and insulin-producing cells. The mechanism of the anti-inflammatory therapeutic effects may be through direct interaction with IκB kinases and inhibiting nuclear factor-κB-regulated gene expression (Ammon 2016). The main mechanism of B. serrata may also be through the elimination of the senescent cells that secrete a group of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and proteases called the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (Xu et al. 2018). These pro-inflammatory mediators are responsible for tissue dysfunction during aging, obesity, and inflammatory diseases (Muñoz-Espín and Serrano 2014). Natural agents such as quercetin and kaempferol (components of B. serrata) have been reported to eliminate cellular senescence in vitro and in mice (Gohel et al. 2018; Lewinska et al. 2020). In vitro and in vivo evidence showed that AKBA significantly promotes peripheral nerve repair and Schwann cell proliferation after rat sciatic nerve injury (Jiang et al. 2018).

The anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects displayed by B. serrata extract suggest a new supportive treatment option in acute systemic inflammation and wound healing (Loeser et al. 2018; Pengzong et al. 2019). Also, B. serrata extract and boswellic acids both counteract free radicals (ROS) and significantly protect the intestinal epithelial barrier from inflammatory damage and inhibit NF-B phosphorylation induced by inflammatory stimuli (Catanzaro et al. 2015). Additionally, acetyl-11-keto-beta-boswellic, in a dose-dependent manner, prevents testicular torsion/detorsion injury in rats with induced upregulation of 5-LOX/LTB4 and p38-MAPK/JNK/Bax pathways and their concomitant inflammatory and apoptotic pathways. It works by inhibiting the 5-LOX/LTB4 and p38-MAPK/JNK/Bax/Caspase-3 pathways (Ahmed et al. 2020). This protective effect is mediated by suppressing levels of intracellular oxygen free radicals, lipid peroxidation, oxidative DNA damage, and inflammation (Sadeghnia et al. 2017; Ahmad et al. 2019). The neuroprotective activities of Boswellia extract and boswellic acids mediated through the inhibition of the oxidative stress were observed also against glutamate toxicity-induced cell injury (Bai et al. 2019; Rajabian et al. 2016, 2020).

There are some clinical studies published in peer-reviewed scientific journals that draw conclusions about the clinical benefit of B. serrata and its phytochemicals in chronic inflammatory diseases. The clinically measurable improvements with B. serrata and its phytochemicals can be achieved in osteoarthritis, multiple sclerosis, bronchial asthma, and psoriasis (Efferth and Oesch 2020; Yu et al. 2020). Moreover, in a preliminary controlled trial in ischemic stroke, B. serrata could improve clinical outcomes in the early phases of stroke along with promising changes in plasma inflammatory factors. The levels of plasma inflammatory markers (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and PGE2) were significantly decreased in the group of patients who received B. serrata for 7 days (Baram et al. 2019). Moreover, boswellic acid and AKBA show promising anti-platelet aggregation effect, anti-profibrotic mechanisms, and improve vascular remodeling by reducing the enhanced oxidative stress and inflammation through the TGFβ1/Smad3 pathway (Tawfik 2016; Shang et al. 2016). These data demonstrate that B. serrata extract and boswellic acids may have beneficial effects against COVID-19-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, clotting formation, and microthrombus, the main cause of the risk of damage to major organs.

Potential therapeutic effects of boswellic acids and B. serrata extract against SARS-CoV-2-induced immune dysregulation

Autoimmune diseases are characterized by an uncontrolled overwhelming immune system reaction with enhanced T cell proliferation. B. serrata extracts and their active ingredients including boswellic acids affect the immune system in different ways (Table 1). Boswellic acids have two different actions on cellular defense: they promoted lymphocyte proliferation in small doses while higher concentrations are inhibitory. In terms of the humoral defense system, boswellic acids also reduced primary antibody titers at higher doses; however, lower doses increased secondary antibody titers. Moreover, boswellic acids enhance the phagocytosis of macrophages (Mikhaeil et al. 2003; Pungle et al. 2003; Ammon 2011; Siddiqui 2011). Beghelli et al. (2017) suggested that B. serrata has a promising potential to modulate not only inflammation/oxidative stress but also immune dysregulation.

Table 1.

Immunomodulatory effects of Boswellia extract and boswellic acids in articles published from 1991 to 2020

| Extract or active ingredient and doses | Method of research | Major finding | Mechanism of action | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanolic extracts of the gum resin exudate of B. serrata. Range between 10 and 80 µg/ml | Suspensions of rat peritoneal polymorphonuclear leukocytes were stimulated by calcium and ionophore to produce leukotrienes and 5-HETE | A concentration-dependent inhibition of LTB4 and 5-HETE production by extract | Anti-inflammatory activity in vivo is mediated by inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase | Ammon et al. (1991) |

|

Boswellic acids (BA) Single or prolonged oral administration of BA (25–100 mg/kg/day for 21 days) |

Sheep erythrocytes SRBC in mice & rats |

Single dose inhibited the expression of the 24-h delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction and primary humoral response to SRBC in mice Multiple oral dose reduced the development of the 24-h DTH reaction and complement fixing antibody titers and slightly enhanced the humoral antibody synthesis |

BA displays immunosuppressive or immunopotentiating effects depending on the dosage and timings of drug administration. BA enhanced the phagocytic function of adherent macrophages | Sharma et al. (1996) |

|

Extract of the gum resin of B. serrata (BS Dosage administered to patients was normally 3 × 2 or 3 × 3 tablets of H15 as a 400 mg extract of BS for 1–6 months |

Clinical study of 260 patients with rheumatoid arthritis via assessment of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), joint stiffness, etc. |

Improvement of criteria for assessment such as joint swelling, pain, ESR, joint stiffness H15 is useful as an adjunct to current disease-modifying drugs |

Unknown | Etzel et al. (1996) |

|

Boswellia carterii Birdwood extract and isolated ingredients 1.00 mg/ml |

Assessment of immunomodulatory activity: lymphocyte blast transformation (mitogensis) assay |

Immunostimulatory activity of the total extract is much greater than that of the individual components; total alcoholic extract shows a significant immunostimulatory action on T lymphocytes (90% lymphocyte proliferation) |

Unknown | Badria et al. (2003a, b) |

| Steam distillation of frankincense essential oil (3%) (B. carterii Birdwood) |

Assessment of the immunomodulatory activity of the oil: lymphocyte blast transformation (mitogensis) assay |

Immunostimulant activity | Unknown | Mikhaeil et al. (2003) |

| Extract of gum resin of B. serrata (doses 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg, po) | Evaluation for antianaphylactic and mast cell stabilizing activity using passive paw anaphylaxis and compound 48/80 induced degranulation of mast cell methods | Inhibited the passive paw anaphylaxis reaction in rats in dose-dependent manner. A significant inhibition in the compound 48/80 induced degranulation of mast cells in dose-dependent manner | Mast cell stabilizing activity | Pungle et al. (2003) |

|

Mixtures of boswellic acids 10 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml, and 200 μg/ml |

In vitro production of TH1 cytokines (interleukin-2 [IL-2] and gamma interferon) and TH2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-10) by murine splenocytes | BAs from B. carterii plant resin exhibit carrier-dependent immunomodulatory properties in vitro | Inhibition of TH1 cytokines coupled with a dose-dependent potentiation of TH2 cytokines | Chervier et al. (2005) |

| Acetyl-alpha-boswellic acid (AαBA) and acetyl-11-keto-beta-boswellic acid (AKβBA) (10 μM) | Monocyte and human embryonic kidney epithelial cell line | AαBA and AKβBA inhibited NF-κB signaling both in LPS-stimulated monocytes as detected by EMSA and in an NF-κB-dependent luciferase gene reporter assay | Selective inhibition of IκBα kinases led to NF-κB-dependent cytokine expression, and that both AαBA and AKβBA are novel selective inhibitors of IKK activity | Syrovets et al. (2005) |

| Methanolic extract of B. serrata and the isolated pure compound. 10 μg/ml, 20 μg/ml, 30 μg/ml, and 50 μg/ml | Human PBMCs (peripheral blood mononuclear cell) culture and mouse macrophages | Marked downregulation of Th1 cytokines IFNγ and IL-12 while the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 were upregulated upon treatment with crude extract and pure compound, 12-ursene 2-diketone, inhibits the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators | Via inhibition of phosphorylation of the MAP kinases JNK and p38 while no inhibition was seen in ERK phosphorylation in LPS-stimulated PBMCs | Gayathri et al. (2007) |

|

Biopolymeric fraction of B. serrata extract Oral (1–10 mg/kg) |

Male BALB/c Mice, PFC assay, HA titer, Complement fixing antibody titer |

Immunostimulatory effect is dose-dependent with respect to macrophage activation | By the enhancement of TNFα and IFNγ production | Khajuria et al. (2008) |

|

Boswellic acids Doses of BA at 100 and 250 mg/kg |

Animal models viz., pyloric ligation, ethanol-HCl, acetylsalicylic acid, indomethacin and cold restrained stress-induced ulceration in rats | BA possess a dose dependent antiulcer effect against different experimental models | Acting by increasing the gastric mucosal resistance and local synthesis of cytoprotective prostaglandins and inhibiting the leukotriene synthesis | Singh et al. 2008a, b b |

|

Boswellic acids (BA)-treated animals with doses of 1.25, 2.5, and 3.75 mg/paw |

Comparative anti-inflammatory (carrageenan paw edema) and anti-arthritic (Mycobacterium-induced arthritis) efficacy of BA via systemic administration and topical application in rats & mice | Anti-inflammatory effect observed through topical route is in accordance with the study conducted with the systemic route | Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase | Singh et al. (2008a) |

| Biopolymeric fraction BOS 2000 from B. serrata (10, 20, 40, and 80 μg) on days 1 and 15 | BALB/c mice were immunized subcutaneously with OVA 100 μg alone or with OVA 100 μg dissolved in saline containing alum (200 μg) or BOS 2000 + spleen cell culture | BOS can enhance the immunogenicity of vaccine/OVA-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a antibody levels in serum | Balanced Th1- and Th2-directing immunological adjuvant | Gupta et al. (2011) |

| B. serrata extract daily 2 tablets with 400 mg for 8.5 weeks |

Female patient, 50 years old, diabetic No improvement with regular treatment |

Additional treatment of B. serrata extract resulted in a drop of IA2-A to normal value | Prevention/treatment of autoimmune diabetes | Schrott et al. (2014) |

| B. serrata (BS) extracts. BS extracts (0.1 μg/ml). AKBA concentration of 3.8–6 ng/ml |

Proliferation assay Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of seven healthy donors |

In vitro lymphocyte proliferation when cells were activated by PWM, the addition of BS extracts induced a significantly higher lymphocyte response BS extract led to a significant increase of FOXP3+ cells. BS modulates not only inflammation/oxidative stress but also immune dysregulation |

Ability to influence the regulatory and effector T cell compartments | Beghelli et al. (2017) |

| Standardized B. serrata extract 400–4800 mg/day) | Enrolled 38 patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) | Oral SFE was safe, tolerated well, and exhibited beneficial effects on RRMS disease activity | Significant increase in regulatory CD4+ T cell markers and a significant decrease in IL-17A-producing CD8+ T cells indicating a distinct mechanism | Stürner et al. (2018) |

|

Standardized B. serrata extract containing boswellic and lupeolic acid 6–44 µg/ml |

LPS-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and whole blood | Nutraceuticals exhibited toxicity against the human triple-negative breast cancer cell and inhibited the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8 | Inhibited growth of cancer xenografts in vivo, and released pro-inflammatory cytokines | Schmiech et al. (2019) |

|

Standardized B. serrata extract 3600–4800 mg/day |

Plasma samples from 28 patients with RRMS who took a standardized frankincense extract (SFE) daily for 8 months | Oral treatment with an SFE significantly reduces 5-LO-derived lipid mediators in patients with RRMS during an 8-month treatment period | Inhibition of 12-,15-LO and cyclooxygenase product levels | Stürner et al. (2020) |

| B. serrata (BS) extract for 9 months | Case study of male patient diagnosed with latent autoimmune diabetes with positive GAD65 autoantibodies | Prevent insulitis in patients with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) | Suppression of autoimmune diabetes markers, i.e., GAD65 and IA2 autoantibodies | Franic et al. (2020) |

| Boswellia sacra essential oil (BSEO) | Normal human skin dermis cell line (HSD) + PBMCs | BSEO exerts suppression effects by inhibition of differentiation, expression of maturation markers, cytokine production, and monocyte-derived DCs stimulated with LPS | Immune suppressor of human peripheral blood monocyte-derived DCs, which may promote the Treg permissive environment | Aldahlawi et al. (2020) |

| B. carterii extract and 3-O-acetyl-alpha-boswellic acid | Cultured cells, lymphocytes were isolated from the blood of healthy adult donors obtained from a blood transfusion center | Inhibited proliferation, degranulation capacity, and secretion of inflammatory mediators of physiologically relevant anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 activated human T lymphocytes in a non-toxic concentration range | Immunosuppressive effects of the extract are based on specific NFAT-conditioned suppression within T cell signaling | Zimmermann-Klemd et al. (2020) |

It is noteworthy that B. serrata gum resin extract decreased IA(2)-antibody in a patient with late-onset autoimmune diabetes of the adult (Schrott et al. 2014). Recently, Franic et al. (2020) confirmed that B. serrata gum resin extract inhibits the production of autoantibodies, GAD65 and IA2, markers of autoimmunity, and prevents autoimmune diabetes. Moreover, Aldahlawi et al. (2020) suggested that B. serrata essential oil (BSEO) has immunomodulatory effects on T cells and dendritic cells. It deflects the differentiation of monocytes into immature dendritic cells (DCs). Stimulation of immature DCs using BSEO was not able to generate full DC maturity. These results can be used to generate DCs with properties capable of inducing tolerance in hypersensitivity and autoimmune diseases (Aldahlawi et al. 2020).

It is important to emphasize the ability of B. serrata to mitigate the uncontrolled activation of the innate immune response and suppress the release of cytokines. It has been observed that lipophilic extract of B. carterii gum resin inhibited the proliferation, degranulation capacity, and secretion of inflammatory mediators of physiologically relevant anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 activated human T lymphocytes in a non-toxic concentration (Zimmermann-Klemd et al. 2020). B. serrata or boswellic acids inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNFα, IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, and IFNγ (Gayathri et al. 2007; Gomaa et al. 2019). Also, many investigators confirmed that B. serrata extracts and their active ingredients boswellic acids significantly inhibited the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 (Schmiech et al. 2019, 2021).

The immunomodulatory effects of B. serrata extract/boswellic acids have a wide range of clinical applications. AKBA enhances osteoblast differentiation in rheumatoid arthritis (RA)-related bone loss disease by inhibiting TNFα and NF-κB where TNFα suppresses osteoblast differentiation by activating NF-κB (Bai et al. 2018). A standardized B. serrata extract reduces disease activity in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis by a significant increase in regulatory CD4+ T cell markers, and a significant reduction in IL-17A-producing CD8+ T cells and bioactive 5-LOX-derived lipid mediators (Stürner et al. 2018; Stürner et al. 2020). It is evident from previous results that B. serrata exracct and boswellic acids may have the potential to enhance the adaptive immune response, and suppress the uncontrolled activation of the innate immune response that leads to cytokine release syndrome and tissue damage in elderly people with COVID-19.

Broad antiviral effect of boswellic acids and B. serrata extract

Although there is no currently published study showing B. serrata activity against SARS-CoV-2, several investigators have shown that B. serrata possesses broad antiviral activity. The antiviral effect of B. serrata was investigated by Goswami et al. (2018). They reported that B. serrata and BA potently inhibited wild-type and a clinical isolate of HSV-1. The inhibitory effect was significant at 1 h post-infection and effective up to 4 h. The mechanism of the antiviral effect of B. serrata extract and BAs was through blocking of NF-κB, necessary for virus replication. B. serrata gum resin extract also has antiviral activity against Chikungunya virus (CHIKV). It blocks the entry of Chikungunya virus Env-pseudotyped lentiviral vectors and inhibited CHIKV infection in vitro. Moreover, B. serrata gum resin extract exhibits antiviral activity against vesicular stomatitis virus, vector particles, and viral infections to the same extent, indicating a broad antiviral activity (Von Rhein et al. 2016).

The strong antiviral activity of the total extract of B. serrata gum resin against the herpes virus was confirmed by Badria et al. (2003a, b). They reported that the activity of the total extract is much greater than that of the individual components. Furthermore, pentacyclic triterpenoids have been documented to have a potential therapeutic role in the treatment of virus infections. For example, research groups have investigated the activity against HIV, HCV, influenza, and other viruses of natural pentacyclic triterpenoids and their semisynthetic derivatives (Xiao et al. 2018). The mechanism of antiviral activity of triterpenoids may be through inhibiting the entry of viruses such as Ebola, Marburg, HIV, and influenza A virus. This action is achieved by wrapping the HR2 domain prevalent in viral envelopes (Si et al. 2018). In addition to the antiviral activity of boswellic acids, flavonoids of B. serrata possess inhibitory activity against many viruses (Zakaryan et al. 2017). On the basis of these studies, it is clear that B. serrata extract and boswellic acids have a broad antiviral activity that may be beneficial in the fight against SARS-CoV-2.

Potential therapeutic effects of boswellic acids and B. serrata extract against COVID-19-induced secondary microbial infections

COVID-19 infection results in significant and persistent lymphopenia in 85% of patients. Furthermore, a person taking immunosuppressants, such as corticosteroids and monoclonal antibodies, may experience severe lymphocytopenia. Because lymphocytes play an important role in the immune defense function against infection, patients with COVID-19 are highly susceptible to bacterial and fungal secondary infections causing a high mortality rate in patients with COVID-19 (Bhatt et al. 2021). About 3.6–13% of patients with COVID-19 developed a secondary bacterial or fungal infection and the mortality rate among these patients was about 33.3–56.7% (Khurana et al. 2021; Vijay et al. 2021). Also, it has been verified that major anaerobic pathogens Tannerella forsythia and Porphyromonas gingivalis in periodontitis are associated with a higher risk of developing a severe secondary infection in patients with COVID-19 (Aquino-Martinez et al. 2021; Marouf et al. 2021; Şehirli et al. 2021), and importantly that patients with COVID-19 have a high probability of suffering from an invasive fungal infection such as mucormycosis, cryptococcosis, aspergillosis, or candidiasis as secondary infection (Song et al. 2020).

Several studies have noted that B. serrata extract or boswellic acids are bacteriostatic at low concentration or bactericidal at high concentration for many gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in vitro and in vivo. According to the findings of Bakhtiari et al. (2019), hydro-alcoholic extract of B. serrata is more effective against Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida krusei, and Streptococcus mutans than organic extract. Hydro-alcoholic extract of B. serrata was most effective against C. albicans and S. mutans. B. serrata also showed antifungal effects (Camarda et al. 2007). Kasali et al.(2002) and Schillaci et al. (2008) Also observed that B. serrata essential oil inhibited C. albicans, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation. AKBA showed an inhibitory effect on all the oral cavity microorganisms. It showed concentration-dependent killing of S. aureus and S. mutans. Moreover, AKBA blocked the formation of biofilms generated by S. aureus S. epidermidis, S. mutants, and Actinomyces viscosus (Raja et al. 2011a, b).

The periodontal infection is polymicrobial of different bacterial species but aggressive forms of this disease have been associated with specific Gram-negative bacteria Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. B. serrata is effective against A. actinomycetemcomitans which may be useful as a suitable oral health medicine and treatment of periodontal infection (Maraghehpour et al. 2016). A double-blind randomized controlled trial was conducted among high school students with moderate plaque-induced gingivitis. B. serrata extract has been safely used to treat and improve the gum health of students. It demonstrated satisfactory medicinal properties, which may be superior to scaling and root planing (SRP) as a conventional method for removing dental plaque (Khosravi Samani et al. 2011).

Many investigators have suggested that AKBA could be a useful agent for developing an antibacterial agent against oral pathogens and it has the potential for use in mouthwash to prevent and treat oral infection (Raja 2011a, b; Patel and Patel 2014). However, Sabra and Al-Masoudi (2014) suggested that B. serrata chewing gum is a safe and low-cost herbal product, which supports mouth hygiene for all ages. It improves buccal/oral cavity hygiene by antimicrobial effects which decrease the sources of microbial infection in the buccal/oral cavity as tested by counting microbial contents of the buccal/oral cavity through microbial identification of saliva.

Several researchers demonstrated the antifungal activity of B. serrata. Essential oil of B. serrata has shown broad antifungal activity against many types of fungal infections and is likely to be a good source of antifungal agents to prevent fungal infections and mycotoxin contamination (Venkatesh et al. 2017). Furthermore, the antimicrobial activity of B. serrata essential oil has been demonstrated against fungal infections, and it has shown synergistic antifungal activity in combination with azoles against the azole-resistant C. albicans (Sadhasivam et al. 2016). Acetone extract of B. serrata was shown to be more effective than ethanol against drug-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus isolated from Diyala patients and has excellent potential as an antifungal agent (Abdul Sattar et al. 2019).

Given the poor bioavailability of B. serrata after oral administration (Sharma et al. 2004; Siddiqui 2011; Sharma et al. 2020), chewing B. serrata gum may lead to better absorption of active ingredients from buccal mucosa. Moreover, the art of chewing B. serrata has other benefits: B. serrata has antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities against oral pathogens and it has great potential for use in preventing and treating oral infections (Raja et al. 2011a, b; Hasson et al. 2011; Bakhtiari et al. 2019; Rad and Taherian 2020). However, chewing B. serrata gum may not be the most effective or easiest way to give B. serrata. In addition, the bioavailability of the active ingredients after conventional use of chewable B. serrata has not yet been published. To overcome the poor bioavailability of the concentrated or isolated boswellic acids, attempts have been made to enhance the bioavailability by the combination of Piper longum (long pepper) and by producing specific compounds such as boswellic acids attached to phospholipids or incorporated into micelles (Hüsch et al. 2013; Meins et al. 2018; Vijayarani et al. 2020). On the basis of the aforementioned studies, it is clear that B. serrata extract and boswellic acids may have a therapeutic effect against virus-induced secondary microbial infection and may be effective in preventing COVID-19 causing secondary infection and COVID-19 causing complications.

Toxicity and safety of B. serrata extract and boswellic acids

Recent studies confirmed that B. serrata extract and boswellic acids possess a high safety margin. Acute oral toxicity studies did not exhibit mortality or signs of toxicity in Wistar rats up to 2000 mg/kg (Alluri et al. 2019). In mice, no death was recorded following the single-dose administration of B. serrata extract at a dose of up to 5 g/kg (Gomaa et al. 2019). Oral administration of the extract for 28 consecutive days did not exhibit any sign of behavioral toxicity and did not show significant changes of biomarkers of hepatic and renal functions as well as the histological characters in rats (Al-Yahya et al. 2020). Moreover, Alluri et al. (2019) demonstrated that repeated oral dose of B. serrata extract for 28 days in Wistar rats did not show dose-related signs of toxicity on the hematology, clinical chemistry, mutagenic, and clastogenic parameters. In previous studies, it was observed that acute oral LD50 of B. serrata extract was greater than 5000 mg/kg in female and male Sprague Dawley rats, and repeated oral dose for 28 or 90 days in Sprague Dawley rats showed no significant adverse changes in hematology, clinical chemistry, gross necropsy, histopathology examinations, and hepatic DNA fragmentation at 30, 60, or 90 days of treatment (Krishnaraju et al. 2010; Singh et al. 2012). Boswellic acids have the same wide spectrum of safety as B. serrata extract. They did not exhibit any sign of toxicity up to 2 g/kg administered orally or intraperitoneally and daily oral administration of BAs in three doses (low and very high) to rats and monkeys revealed no significant changes in general behavior or clinical, hematological, biochemical, and pathological parameters (Singh et al. 1996; Lalithakumari et al. 2006).

Perspectives

We propose that B. serrata extract in small to moderate dose (100–200 mg/day) can be used in early stages in mild to moderate symptoms of COVID-19 to enhance the adaptive immune response. However a large dose of B. serrata extract or boswellic acid can be used to suppress the uncontrolled activation of the innate immune response that leads to cytokine storm. Because of the low oral bioavailability and improvement of buccal/oral cavity hygiene, traditional use by chewing B. serrata gum may be more beneficial in mild to moderate symptoms and as prophylactic. Also, it may be the cheapest option for a lot of poorer people; however, it may not be the most effective or easiest way of administering B. serrata. B. serrata extract or boswellic acid may be used also as a prophylactic agent in combination with other natural antiviral agents such as licorice for the prevention of progression of the COVID-19 (Gomaa and Abdel-wadood 2021). This combination can be considered as one of the best suggested natural regimens for the prevention of COVID-19. Since this regimen has a high safety margin, it is now under clinical trial to determine its therapeutic efficacy in patients with COVID-19 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04487964).

Conclusions

Given the pharmacological and clinical evidence, there may be a use for B. serrata in treating similar symptoms experienced by patients with COVID-19. The potential therapeutic effects of boswellic acids and B. serrata extract are attributed mainly to its anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, cardioprotective, anti-platelet aggregation, antibacterial, antifungal, and broad antiviral activity. Because of the low oral bioavailability and improvement of buccal/oral cavity hygiene, traditional use by chewing B. serrata gum may be a good, and only, option for poorer people. The main mechanism of therapeutic effects may be through direct interaction with IκB kinases and inhibiting nuclear factor-κB-regulated gene expression. However, the most recent mechanism proposed that BA not only inhibited the formation of classical 5-lipoxygenase products but also caused a switch from the production of pro-inflammatory leukotienes to formation of anti-inflammatory LOX-isoform-selective modulators. Although the non-clinical studies acknowledge the usefulness of boswellic acids and B. serrata extract in treating COVID-19, these data reinforce the idea that more clinical results are required to determine with certainty whether there is sufficient evidence of the benefits of B. serrata extract and boswellic acids against COVID-19.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- B. serrata

Boswellia serrata

- BA

Boswellic acids

- KBA

11-Keto-β-boswellic acid

- AKBA

3-O-Acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid

- ACE2

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- Bax

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- COX-2

Cyclooxygenase-2

- GATA3

GATA binding protein 3

- GSK-3β

Glucogen synthase kinase-3 beta

- GSH

Glutathione

- HLE

Human leukocyte elastase

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1 beta

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- JAK

Janus kinase

- JNK

C-Jun N-terminal kinase

- KBA

11-Keto-β-boswellic acid

- 5-LOX

5-Lipoxygenase

- LTB4

Leukotriene B4

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- MERS-CoV

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa B

- SASP

Senescence-associated secretory phenotype

- SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

- STAT

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

Author contributions

AAG: resources, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision. HSM: writing—review and editing. RBA: writing—review and editing. MAG: writing—review and editing.

Funding

This study was not funded by any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-proft sectors.

Data availability

Data on relevant human studies in the current review (https://drive.google.com/file/d/17YZvAhCFoBMV6vdnjLFzfNN52vtpCKri/view?usp=sharing).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdul SO, Fadhel S, Ismael T, Hussain A. Antifungal activity of Boswellia serrata gum extracts on antifungal drugs resistant Aspergillus fumigatus isolated from Diyala patients. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2019;10(11):4929–4934. doi: 10.37506/ijphrd.v10i11.8914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Khan SA, Kindelin A, Mohseni T, Bhatia K, Hoda M, Ducruet AF. Acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (AKBA) attenuates oxidative stress, inflammation, complement activation and cell death in brain endothelial cells following OGD/reperfusion. Neuromol Med. 2019;21:505–516. doi: 10.1007/s12017-019-08569-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed MAE, Ahmed AAE, El Morsy EM. Acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid prevents testicular torsion/detorsion injury in rats by modulating 5-LOX/LTB4 and p38-MAPK/JNK/Bax/caspase-3 pathways. Life Sci. 2020;260:118472. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldahlawi AM, Alzahrani AT, Elshal MF. Evaluation of immunomodulatory effects of Boswellia sacra essential oil on T cells and dendritic cells. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20(1):352. doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-03146-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali EN, Mansour SZ. Boswellic acids extract attenuates pulmonary fibrosis induced by bleomycin and oxidative stress from gamma irradiation in rats. Chin Med. 2011;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jawad FH, Al-Razzuqi RA, Hashim HM, et al. Glycyrrhiza glabra versus Boswellia carterii in chronic bronchial asthma: a comparative study of efficacy. Indian J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;26:6–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-6691.104437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alluri VK, Dodda S, Kilari EK, et al. Toxicological assessment of a standardized Boswellia serrata gum resin extract. Int J Toxicol. 2019;38:423–435. doi: 10.1177/1091581819858069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Yahya AA, Asad M, Sadaby A, et al. Repeat oral dose safety study of standardized methanolic extract of Boswellia sacra oleo gum resin in rats. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020;27:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.05.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammon HP. Modulation of the immune system by Boswellia serrata extracts and boswellic acids. Phytomedicine. 2011;15:334. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammon HP. Boswellic acids and their role in chronic inflammatory diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;928:291–327. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-41334-1_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammon HP, Mack T, Singh GB, Safayhi H. Inhibition of leukotriene B4 formation in rat peritoneal neutrophils by an ethanolic extract of the gum resin exudates of Boswellia serrata. Planta Med. 1991;57:203–207. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino-Martinez R, Hernández-Vigueras S. Severe COVID-19 lung infection in older people and periodontitis. J Clin Med. 2021;10:279. doi: 10.3390/jcm10020279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayub M, Hanif M, Sarfraz R, et al. Biological activity of Boswellia serrata Roxb. oleo gum resin essential oil: effects of extraction by supercritical carbon dioxide and traditional methods. Int J Food Prop. 2018;21:808–820. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2018.1439957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badria FA, Abu-Karam M, Mikhaeil BR, et al. Anti-herpes activity of isolated compounds from frankincense. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia. 2003;1(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Badria FA, Mikhaeil BR, Maatooq GT, Amer MM. Immunomodulatory triterpenoids from the oleogum resin of Boswellia carterii Birdwood. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2003;58:505–516. doi: 10.1515/znc-2003-7-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F, Chen X, Yang H, Xu HG. Acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid promotes osteoblast differentiation by inhibiting tumor necrosis factor-α and nuclear factor-κb activity. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29:1996–2002. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J, Gao Y, Chen L, Yin Q, Lou F, Wang Z, Xu Z, et al. Identification of a natural inhibitor of methionine adenosyltransferase 2A regulating one-carbon metabolism in keratinocytes. EBioMedicine. 2019;39:575–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj V, Gadi N, Spihlman AP, Wu SC, Choi CH, Moulton VR. Aging, immunity, and COVID-19: how age influences the host immune response to coronavirus infections? Front Physiol. 2021;11:571416. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.571416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiari S, Nematzade F, Hakemi-Vala M, Talebi G. Phenotypic investigation of the antimicrobial effect of organic and hydro-alcoholic extracts of boswellia serrata on oral microbiota. Front Dent. 2019;16:386–392. doi: 10.18502/fid.v16i5.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baram SM, Karima S, Shateri S, et al. Functional improvement and immune-inflammatory cytokines profile of ischaemic stroke patients after treatment with boswellic acids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial. Inflammopharmacology. 2019;27:1101–1112. doi: 10.1007/s10787-019-00627-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beghelli D, Isani G, Roncada P, et al. Antioxidant and ex vivo immune system regulatory properties of Boswellia serrata extracts. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/7468064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertocchi M, Isani G, Medici F, Andreani G, Tubon Usca I, Roncada P, Forni M, Bernardini C. Anti-inflammatory activity of Boswellia serrata extracts: an in vitro study on porcine aortic endothelial cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/2504305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt K, Agolli A, Patel MH, et al. High mortality co-infections of COVID-19 patients: mucormycosis and other fungal infections. Discoveries (Craiova) 2021;9(1):e126. doi: 10.15190/d.2021.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth CE, vanDonzel E, Lewis E, Pellet CH. The encyclopedia of Islam. Leiden: EJ Bril; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Camarda L, Dayton T, Di Stefano V, Pitonzo R, Schillaci D. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of some oleogum resin essential oils from Boswellia spp. (Burseraceae) Ann Chim. 2007;97:837–844. doi: 10.1002/adic.200790068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro D, Rancan S, Orso G, Dallcqua S, Brun P, Giron MC, Carrara M, et al. Boswellia serrata preserves intestinal epithelial barrier from oxidative and inflammatory damage. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Klein SL, Garibaldi BT, et al. Aging in COVID-19: vulnerability, immunity and intervention. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;65:101205. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervier MR, Ryan AE, Lee DY, Zhongze M, Wu-Yan Z, Via CS. Boswellia carterii extract inhibits TH1 cytokines and promotes TH2 cytokines in vitro. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;1:575–580. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.5.575-580.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha LL, Perazzio SF, Azzi J, Cravedi P, Riella LV. Remodeling of the immune response with aging: immunosenescence and its potential impact on COVID-19 immune response. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1748. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AC, Goh HP, Koh D. Treatment of COVID-19: old tricks for new challenges. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2818-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L, Hu S, Gao J. Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Drug Discov Ther. 2020;14:58–60. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2020.01012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Redeploying plant defences. Nat Plants. 2020;6:177. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Sherlock P, Ebrahim S, Geffen L, McKee M. Bearing the brunt of covid-19: older people in low and middle income countries. BMJ. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T, Oesch F. Anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities of frankincense: targets, treatments and toxicities. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltahir HM, Fawzy MA, Mohamed EM, et al. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects of Boswellia serrate gum resin in CCl4-induced hepatotoxicity. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19:1313–1321. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.8353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzel R. Special extract of Boswellia serrata (H15) in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Phytomedicine. 1996;3:91–94. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(96)80019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedson DS. Treating the host response to emerging virus diseases: lessons learned from sepsis, pneumonia, influenza and Ebola. Ann Tran Med. 2016;4:421. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.11.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara T, De Vincentiis G, Di Pierro F. Functional study on Boswellia phytosome as complementary intervention in asthmatic patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:3757–3762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firenzuoli F, Antonelli M, Donelli D, Gensini GF, Maggini V. Cautions and opportunities for botanicals in COVID-19 patients: a comment on the position of the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety. J Altern Complement Med. 2020;10:851–853. doi: 10.1089/acm.2020.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forouzanfar F, Hosseinzadeh H, Ebrahimzadeh Bideskan A, Sadeghnia HR. Aqueous and ethanolic extracts of boswellia serrata protect against focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury in rats. Phytother Res. 2016;12:1954–1967. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franić Z, Franić Z, Vrkić N, Gabaj NN, Petek I. Effect of extract from Boswellia serrata gum resin on decrease of GAD65 autoantibodies in a patient with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults. Altern Ther Health Med. 2020;26:38–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends. 2020;14:72–73. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label nonrandomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Gayathri B, Manjula N, Vinaykumar KS, et al. Pure compound from Boswellia serrata extract exhibits anti-inflammatory property in human PBMCs and mouse macrophages through inhibition of TNFalpha, IL-1beta, NO and MAP kinases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert NC, Gerstmeier J, Schexnaydre EE, Börner F, Garscha U, Neau DB, Werz O, Newcomer ME. Structural and mechanistic insights into 5-lipoxygenase inhibition by natural products. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16:783–790. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-0544-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohel K, Patel K, Shah P, et al. Box-Behnken design-assisted optimization for simultaneous estimation of quercetin, kaempferol, and keto-[beta]-boswellic acid by high-performance thin-layer chromatography method. J Planar Chromatogr Mod TLC. 2018;31:318–325. doi: 10.1556/1006.2018.31.4.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa AA, Abdel-Wadood YA. The potential of glycyrrhizin and licorice extract in combating COVID-19 and associated conditions. Phytomed Plus. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.phyplu.2021.100043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa AA, Makboul R, Al-Mokhtarc M, et al. Polyphenol-rich boswellia serrata gum prevents cognitive impairment and insulin resistance of diabetic rats through inhibition of GSK3β activity, oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami D, Mahapatra AD, Banerjee S, Kar A, Ojha D, Mukherjee PK, Chattopadhyay D. Boswellia serrata oleo-gum-resin and β-boswellic acid inhibits HSV-1 infection in vitro through modulation of NF-кB and p38 MAP kinase signaling. Phytomedicine. 2018;51:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta I, Gupta V, Parihar S, et al. Effect of Boswellia serrata gum resin in patient with bronchial asthma: results of a double blind, placebo controlled 6 week clinical study. Eur J Med Res. 1998;3:511–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Khajuria A, Singh J, Singh S, Suri KA, Qazi GN. Immunological adjuvant effect of Boswellia serrata (BOS 2000) on specific antibody and cellular response to ovalbumin in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:968–975. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson SS, Al-Balushi MS, Sallam TA, Idris MA, Habbal O, Al-Jabri AA. In vitro antibacterial activity of three medicinal plants-Boswellia (Luban) species. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011;1:S178–S182. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60151-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hewedy WA. Effect of Boswellia serrata on rat trachea contractility in vitro. Nat Prod J. 2020;10:33–43. doi: 10.2174/2210315509666190206122050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houssen ME, Ragab A, Mesbah A, et al. Natural anti-inflammatory products and leukotriene inhibitors as complementary therapy for bronchial asthma. Clin Biochem. 2010;43(10–11):887–890. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hüsch J, Bohnet J, Fricker G, Skarke C, Artaria C, Appendino G, et al. Enhanced absorption of boswellic acids by a lecithin delivery form (Phytosome®) of Boswellia extract. Fitoterapia. 2013;84:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XW, Zhang BQ, Qiao L, et al. Acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid extracted from Boswellia serrata promotes Schwann cell proliferation and sciatic nerve function recovery. Neural Regen Res. 2018;13:484–491. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.228732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadambari S, Klenerman P, Pollard AJ. Why the elderly appear to be more severely affected by COVID-19: the potential role of immunosenescence and CMV. Rev Med Virol. 2020;30(5):e2144. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasali AA, Adio AM, Kundaya OE, Oyedeji AO, Eshilokun AO, Adefenwa M. Antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Boswellia serrata Roxb. J Essent Oil Bear Plants. 2002;5(3):173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Katragunta K, Siva B, Kondepudi N, Vadaparthi PR, Rama Rao N, et al. Estimation of boswellic acids in herbal formulations containing Boswellia serrata extract and comprehensive characterization of secondary metabolites using UPLC-Q-Tof-MSe. J Pharm Anal. 2019;9(6):414–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khajuria A, Gupta A, Suden P, Singh S, Malik F, Singh J, Gupta BD, Suri KA, et al. Immunmodulatoryactivity of biopolymeric fraction BOS 2000 from Boswellia serrata. Phytother Res. 2008;22:340–348. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi M, Mahmoodian H, Moghadamnia A, Poorsattar A, Chitsazan M. The effect of frankincense in the treatment of moderate plaque-induced gingivitis: a double blinded randomized clinical trial. Daru. 2011;19(4):288–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana S, Singh P, Sharad N, et al. Profile of co-infections & secondary infections in COVID-19 patients at a dedicated COVID-19 facility of a tertiary care Indian hospital: implication on antimicrobial resistance. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2021;39(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmmb.2020.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Lee JY, Yang JW, Lee KH, Effenberger M, Szpirt W, Kronbichler A, Shin JI. Immunopathogenesis and treatment of cytokine storm in COVID-19. Theranostics. 2021;11(1):316–329. doi: 10.7150/thno.49713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaraju AV, Sundararaju D, Vamsikrishna U, et al. Safety and toxicological evaluation of Aflapin: a novel Boswellia-derived anti-inflammatory product. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2010;20(9):556–563. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2010.497978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalithakumari K, Krishnaraju AV, Sengupta K, et al. Safety and toxicological evaluation of a novel, standardized 3-O-acetyl-11-keto-beta-boswellic acid (AKBA)-enriched Boswellia serrata extract (5-Loxin®) Toxicol Mech Methods. 2006;16(4):199–226. doi: 10.1080/15376520600620232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinska A, Adamczyk-Grochala J, Bloniarz D, et al. AMPK-mediated senolytic and senostatic activity of quercetin surface functionalized Fe3O4 nanoparticles during oxidant-induced senescence in human fibroblasts. Redox Biol. 2020;28:101337. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Liu X, Sang L, et al. Boswellic acid attenuates asthma phenotypes by downregulation of GATA3 via pSTAT6 inhibition in a murine model of asthma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(1):236–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeser K, Seemann S, König S, et al. Protective effect of casperome R, an orally bioavailable frankincense extract, on lipopolysaccharide induced systemic inflammation in mice. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:387. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Tang QL, Shang YX, et al. Can Chinese medicine be used for prevention of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? A review of historical classics, research evidence and current prevention programs. Chin J Integr Med. 2020;26(4):243–250. doi: 10.1007/s11655-020-3192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malavolta M, Giacconi R, Brunetti D, et al. Exploring the relevance of senotherapeutics for the current SARS-CoV-2 emergency and similar future global health threats. Cells. 2020;9(4):909. doi: 10.3390/cells9040909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maraghehpour B, Khayamzadeh M, Najafi S, Kharazifard M. Traditionally used herbal medicines with antibacterial effect on Aggegatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: Boswellia serrata and Nigella sativa. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2016;20(6):603–607. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_12_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marouf N, Cai W, Said KN, et al. Association between periodontitis and severity of COVID-19 infection: a case–control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meins J, Behnam D, Abdel-Tawab M. Enhanced absorption of boswellic acids by a micellar solubilized delivery form of Boswellia extract. NFS J. 2018;11:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.nfs.2018.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miao XD, Zheng LJ, Zhao ZZ, Su SL, Zhu Y, et al. Protective effect and mechanism of boswellic acid and myrrha sesquiterpenes with different proportions of compatibility on neuroinflammation by LPS-induced BV2 cells combined with network pharmacology. Molecules. 2019;24(21):3946. doi: 10.3390/molecules24213946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhaeil BR, Maatooq GT, Badria FA, et al. Chemistry and immunomodulatory activity of frankincense oil. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2003;58(3–4):230–238. doi: 10.1515/znc-2003-3-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Espín D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:482–496. doi: 10.1038/nrm3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NB, Patel KC. Antibacterial activity of Boswellia serrata Roxb. ex colebr ethnomedicinal plant against gram positive UTI pathogens. Life Sci Leafl. 2014;53:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pengzong Z, Yuanmin L, Xiaoming X, et al. Wound healing potential of the standardized extract of Boswellia serrata on experimental diabetic foot ulcer via inhibition of inflammatory, angiogenetic and apoptotic markers. Planta Med. 2019;85(8):657–669. doi: 10.1055/a-0881-3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pum A, Ennemoser M, Adage T, Kungl AJ. Cytokines and chemokines in SARS-CoV-2 infections-therapeutic strategies targeting cytokine storm. Biomolecules. 2021;11(1):91. doi: 10.3390/biom11010091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pungle P, Banavalikar M, Suthar A, et al. Immunomodulatory activity of boswellic acids of Boswellia serrata Roxb. Indian J Exp Biol. 2003;41(12):1460–1462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rad MZ, Taherian H. Effect of mouthwash with Boswellia extract on the prevention of dental plaque formation in patients under mechanical ventilation. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2020;9:77–82. doi: 10.4103/nms.nms_65_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raja AF, Ali F, Khan IA, Shawl AS, Arora DS, Shah BA, Taneja SC. Antistaphylococcal and biofilm inhibitory activities of acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid from Boswellia serrata. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja AF, Al F, Khan IA, Shawl AS, Arora DS. Acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (AKBA); targeting oral cavity pathogens. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:406. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajabian A, Boroushaki MT, Hayatdavoudi P, Sadeghnia HR. Boswellia serrata protects against glutamate-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in PC12 and N2a cells. DNA Cell Biol. 2016;35(11):666–679. doi: 10.1089/dna.2016.3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajabian A, Sadeghnia HR, Hosseini A, Mousavi SH, Boroushaki MT. 3-Acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid attenuated oxidative glutamate toxicity in neuron-like cell lines by apoptosis inhibition. J Cell Biochem. 2020;121(2):1778–1789. doi: 10.1002/jcb.29413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashan L, Hakkim FL, Idrees M, et al. Boswellia gum resin and essential oils: potential health benefits—an evidence based review. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis. 2019;9:53–71. doi: 10.4103/ijnpnd.ijnpnd_11_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Garcia JL, Sanchez-Nievas G, Arevalo-Serrano J, Garcia-Gomez C, et al. Baricitinib improves respiratory function in patients treated with corticosteroids for SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: an observational cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60(1):399–407. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.10243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy NK, Parama D, Banik K, Bordoloi D, Devi AK, et al. An update on pharmacological potential of boswellic acids against chronic diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(17):4101. doi: 10.3390/ijms20174101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabra SM, Al-Masoudi LM. The effect of using frankincense (Boswellia sacra) chewing gum on the microbial contents of buccal/oral cavity, Taif, KSA. J Dent Med Sci. 2014;13(4):77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghnia HR, Arjmand F, Ghorbani A. Neuroprotective effect of boswellia serrate and its active constituent acetyl 11-keto-β-boswellic acid against oxygen-glucose serum deprivation-induced cell injury. Acta Pol Pharm. 2017;74(3):911–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadhasivam S, Palanivel S, Ghosh S. Synergistic antimicrobial activity of Boswellia serrata Roxb. ex Colebr. (Burseraceae) essential oil with various azoles against pathogens associated with skin, scalp and nail infections. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2016;63(6):495–501. doi: 10.1111/lam.12683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safayhi H, Rall B, Sailer ER. Inhibition by boswellic acids of human leukocyte elastase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281(1):460–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillaci D, Arizza V, Dayton T, Camarda L, Di Stefano V. In vitro anti-biofilm activity of Boswellia spp. oleogum resin essential oils. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2008;47(5):433–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiech M, Lang SJ, Ulrich J, Werner K, Rashan LJ, Syrovets T, Simmet T. Comparative investigation of frankincense nutraceuticals: correlation of boswellic and lupeolic acid contents with cytokine release inhibition and toxicity against triple-negative breast cancer cells. Nutrients. 2019;11(10):2341. doi: 10.3390/nu11102341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiech M, Ulrich J, Lang SJ, Büchele B, Paetz C, St-Gelais A, et al. 11-Keto-α-boswellic acid, a novel triterpenoid from Boswellia spp. with chemotaxonomic potential and antitumor activity against triple-negative breast cancer cells. Molecules. 2021;26(2):366. doi: 10.3390/molecules26020366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrott E, Laufer S, Lämmerhofer M, Ammon HP. Extract from gum resin of Boswellia serrata decreases IA(2)-antibody in a patient with "late onset autoimmune diabetes of the adult" (LADA) Phytomedicine. 2014;21(6):786. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şehirli AÖ, Aksoy U, Koca-Ünsal RB, Sayıner S. Role of NLRP3 inflammasome in COVID-19 and periodontitis: possible protective effect of melatonin. Med Hypotheses. 2021;151:110588. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2021.110588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seif F, Aazami H, Khoshmirsafa M, Kamali M, Mohsenzadegan M, Pornour M, Mansouri D. JAK inhibition as a new treatment strategy for patients with COVID-19. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2020;181(6):467–475. doi: 10.1159/000508247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang P, Liu W, Liu T, et al. Acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid attenuates prooxidant and profibrotic mechanisms involving transforming growth factor-β1, and improves vascular remodeling in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39809. doi: 10.1038/srep39809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma T, Jana S. Investigation of molecular properties that influence the permeability and oral bioavailability of major β-boswellic acids. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2020;45:243–255. doi: 10.1007/s13318-019-00599-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma ML, Kaul A, Khajuria A, Singh S, Singh GB. Immunomodulatory activity of boswellic acids (pentacyclic triterpene acids) from Boswellia serrata. Phytother Res. 1996;10:107–112. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199603)10:2<107::AID-PTR780>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Thawani V, Hingorani L, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of 11-keto-b-boswellic acid. Phytomed. 2004;11:1255–1260. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si L, Meng K, Tian Z, et al. Triterpenoids manipulate a broad range of virus-host fusion via wrapping the HR2 domain prevalent in viral envelopes. Sci Adv. 2018;11:eaau8408. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau8408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui MZ. Boswellia serrata, a potential anti-inflammatory agent: an overview. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2011;73:255–261. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.93507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GB, Bani S, Singh S. Toxicity and safety evaluation of boswellic acids. Phytomed. 1996;3:87–90. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(96)80018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Khajuria A, Taneja SC, Johri RK, et al. Boswellic acids: a leukotriene inhibitor also effective through topical application in inflammatory disorders. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Khajuria A, Taneja SC, Johri RK, et al. The gastric ulcer protective effect of boswellic acids, a leukotriene inhibitor from Boswellia serrata, in rats. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Chacko KM, Aggarwal ML, et al. A-90 day gavage safety assessment of Boswellia serrata in rats. Toxicol Int. 2012;19(3):273–278. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.103668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK, Singh A, Shaikh A, et al. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 with or without diabetes: a systematic search and a narrative review with a special reference to India and other developing countries. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G, Liang G, Liu W. Fungal co-infections associated with global covid-19 pandemic: a clinical and diagnostic perspective from China. Mycopathologia. 2020;185(4):599–606. doi: 10.1007/s11046-020-00462-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni KK, Meshram D, Lawal TO, et al. Fractions of Boswellia serrata suppress LTA4, LTC4, cyclooxygenase-2 activities and mRNA in HL-60 cells and reduce lung inflammation in BALB/c mice. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2020 doi: 10.2174/1570163817666200127112928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbing J, Phelan A, Griffin I, Tucker C, Oechsle O, Smith D, Richardson P. COVID-19: combining antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatments. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:400–402. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30132-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbing J, Sánchez Nievas G, Falcone M, Youhanna S, Richardson P, et al. JAK inhibition reduces SARS-CoV-2 liver infectivity and modulates inflammatory responses to reduce morbidity and mortality. Sci Adv. 2021;7(1):eabe4724. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe4724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stürner KH, Stellmann JP, Dörr J, Paul F, Friede T, Schammler S, Reinhardt S, et al. A standardised frankincense extract reduces disease activity in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (the SABA phase IIa trial) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(4):330–338. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stürner KH, Werz O, Koeberle A, Otto M, Pless O, Leypoldt F, Paul F, Heesen C. Lipid mediator profiles predict response to therapy with an oral frankincense extract in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8776. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65215-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrovets T, Buchele B, Krauss C, Laumonnier Y, Simmet T. Acetyl-boswellic acids inhibit lipopolysaccharide-mediated TNF-alpha induction in monocytes by direct interaction with IkappaB kinase. J Immunol. 2005;174:498. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik MK. Anti-aggregatory effect of boswellic acid in high-fat fed rats: involvement of redox and inflammatory cascades. Arch Med Sci. 2016;12(6):1354–1361. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.60675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]