Abstract

Endometriosis is a benign estrogen-dependent disorder affecting women in their reproductive age group. Endometriosis means ‘abnormal growth of endometrial glands’ outside the uterus. Multiple theories on aetiopathogenesis of endometriosis have been postulated, Halban’s theory on ‘Benign Metastasis’ which proposed the presence of endometriotic cells in lymphatic vessels and lymph nodes provides the basis of this case report. Here, we report a case of 26-year-old nulliparous woman who presented with grossly elevated CA 125 with endometriosis in her para-aortic nodes mimicking as ovarian cancer.

Keywords: cancer - see oncology, obstetrics, gynaecology and fertility, reproductive medicine, gynecological cancer

Background

Endometriosis is a debilitating condition affecting women of reproductive age group, but prompt recognition and effective treatment can greatly improve outcomes. The disease very much exhibits features of malignancy such as its ability to invade and metastasise with elevated tumour markers. Hence, it is essential to emphasise the benign nature of the disease and provide wholesome treatment with good prognosis.

Case presentation

This patient is a 26-year-old woman, known diabetic with a history of primary infertility for 6 years. She presented with history of lower abdominal pain and bleeding per vaginum for more than a year. She had undergone laparoscopic cystectomy for ovarian cyst 6 years ago and had undergone dilatation and curettage in the past for infertility workup. She was diagnosed with adnexal mass elsewhere and was planned for surgery, which was abandoned as there were dense adhesions between utero-ovarian cystic complex and anterior wall of the rectum.

On admission, physical examination revealed a mass in the lower abdomen extending up to the umbilicus. Per vaginal examination revealed fullness in fornices, with no palpable pelvic nodules.

On evaluation, her CA 125 was grossly elevated (1718 U/mL). CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a cystic mass in the pouch of Douglas, with loss of fat plane with posterior wall of the uterus and sigmoid colon, minimal free fluid and enlarged para-aortic node (3 cm). Given the presence of enlarged para-aortic node with ovarian mass, and high

CA-125, differential of ovarian malignancy was entertained more than non-malignant causes.

A guided biopsy was done which tuned out to be inconclusive.

She was explained the possibilities of endometriotic cyst/ovarian malignancy with para-aortic nodal spread and possible need for surgical extirpation because of previous intraoperative findings. She agreed for possible radical surgery, with resultant permanent infertility.

Following which the patient was planned for exploratory laparotomy.

Intraoperatively, she had a large cystic mass, arising from the ovary, densely adherent to the posterior wall of the uterus, sigmoid colon and with minimal adhesion to the ileum. She underwent total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with pelvic and para-aortic node sampling.

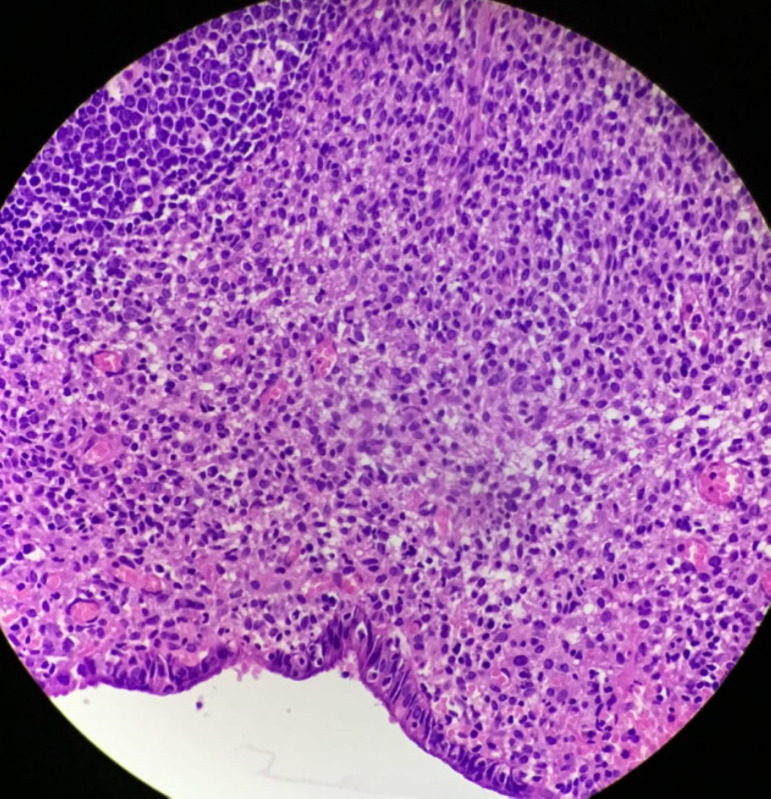

Histopathological examination revealed the presence of an endometriotic cyst in the ovary with invasive endometriosis onto the fallopian tube, sigmoid colon and ileal adhesion. The para-aortic nodes sampled also revealed the presence of endometriosis in it (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

H&E (×100)—node showing endometriotic tissue and stroma.

Figure 2.

H&E (×400)—node showing endometriotic tissue with haemosiderin laden macrophages.

Investigations

CA 125 was 1718 U/mL.

CT of abdomen and pelvis revealed a mass in the Pouch of Douglas (POD) with loss of fat plane with posterior wall of uterus and sigmoid colon. Enlarged para-aortic node of 3 cm.

Image guided biopsy was inconclusive.

Differential diagnosis

Carcinoma ovary was a close differential diagnosis given the clinical and radiological presentation. However, other tumour markers such as beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), alpha fetoprotein (AFP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), Cancer Antigen 19-9 (CA 19–9) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) turned out to be negative. Image-guided biopsy was inconclusive.

Carcinoma endometrium with pelvic and para-aortic metastasis. Endometrial biopsy was done and was normal.

Pelvic tuberculosis can also present with similar clinical findings, but elevated tumour markers is relatively rare here. Also, the clinical features and blood picture (normal white blood counts and inflammatory markers) did not favour the diagnosis of pelvic tuberculosis.

Discussion

Endometriosis implies the presence of extrauterine endometrial tissue. This usually painful condition seen in 50% of all infertile women, and 70% of those with chronic pelvic pain.1

Pathogenetically, Sampson’s theory of implantation is presently the most accepted. It proposes retrograde menstruation of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity through the fallopian tubes, which gets implanted, with subsequent development of endometriosis.2

The presentation and evolution of the disease are variable; in some cases, the disease can persist as minimal or mild disease, or the disease can even disappear with increasing age. Other cases can show severe symptomatology because of tissue invasion, development of chocolate cysts, distressing pelvic adhesions or pelvic blockade that can affect other organs. Strong genetic link between endometriosis and malignant ovarian tumours, especially endometrioid and clear cell adenocarcinoma have been found. Mutations in AT-Rich Interaction Domain 1A (ARID1A) have been found in clear cell (46%–57%) and endometrioid ovarian adenocarcinomas (30%).3 Endometriosis may develop anywhere within the pelvis and extrapelvic peritoneal surfaces. Implants can be either superficial or deeply infiltrative endometriosis (DIE). This DIE is of serious concern as it can infiltrate adjacent structures such as bowel, bladder and ureters. Some definitions of DIE also quantify the invasions as >5 mm in depth.

Endometriosis, particularly the DIE, is a debilitating condition, posing significant quality of life issues for an individual patient. The diagnosis is usually confirmed with surgery, frequently with laparoscopy.

Endometriosis is traditionally considered a benign disease. But endometriosis, especially deeply invasive endometriosis, shares characteristics of malignancy, such as the invasion of tissues, neovascularisation, unrestricted growth, potential to metastasise and chronic inflammation.4

Possible intestinal or urological complications such as obstruction of the rectosigmoid, bowel infiltration, bladder invasion or ureters’ stenosis can occur and often require extensive surgical intervention.5 Data also show that genomic instability in endometriosis may lead to mechanisms similar to those that cause carcinogenesis.6 It is considered that ovarian cancer develops in 1%–5% of ovarian endometriosis.7 This proposed incidence of malignancy in endometriosis may be an underestimate, as the developing malignant cells may obliterate the previous endometriotic lesions and the benign to malignant transformation,.8

Para-aortic lymph node spread is a very rare occurrence in endometriosis. Javert first described endometriosis in lymph nodes as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma without the evidence of atypia.9 Two cases have been reported previously, with this being the third case10 11 (table 1).

Table 1.

Reported cases of endometriosis in the para-aortic node

| Author | Year | Age (years) | Associated lesions | Size of para-aortic node |

| Beavis (2) | 2011 | 25 | Adnexal mass with obturator node in pregnancy | 2.4 cm |

| Escobar (10) | 2013 | 23 | Adnexal mass | Not mentioned |

| Present case | 2020 | 26 | Adnexal mass | 3 cm |

Two theories have explained the nodal involvement in endometriosis. The first one delineates it as metaplastic from the secondary müllerian system, which later differentiates into müllerian-directed tissue.12 The second theory states lymph node involvement as metastatic from the endometriotic tissue.7 Also lymphangiogenic promoters and density of lymphatics are increased in ectopic endometriotic tissue.13 This case supports the metastatic theory of the spread of endometriotic tissue through lymphatics.

Noel showed involvement of lymph nodes in 42.3% of rectosigmoidectomy for DIE.14 Similarly, Abrao et al reported 26.3% lymph node involvement after proctosigmoidectomy for deep endometriosis.15 These nodes if not removed at surgery may be a potential target for hormonal stimulation and can be a probable source of disease recurrence.16

Patient’s perspective.

Infertility has always been the greatest bane of my life. In an attempt to sought treatment and effectively cure the underlying condition, I had taken multiple fertility drugs and treatment thereby exposing myself to various hormones. The presenting complaint and further investigations being suspicious of malignancy, I agreed for a radical surgery with resulting permanent infertility. A precise diagnosis was difficult to obtain in my condition before surgery, maybe if there were precise non invasive methods of making a diagnosis prior it would’ve helped with my condition.

Learning points.

Para-aortic lymph nodal spread of endometriosis is a rare entity and should be borne in mind treating patients with atypical presentations of endometriosis.

All cases presenting with ovarian mass and lymph node involvement is not necessarily malignant.

Understanding the aetiopathogenesis of endometriosis will enable prompt treatment and effective follow-up in such cases.

Footnotes

Contributors: This case presented to the surgical oncology department of Sri Ramachandra Medical college. Evaluation, investigations and follow up of the case was done by SS, Jegadesh Bose, BV and SK. Preoperative analysis and fitness for surgery obtained. Surgery was done by Jegadesh bose and SS. Follow-up of histopathology reports and patient follow up was done by BV and SK.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Nardi PD, Ferrrari S. Deep Pelvic Endometriosis: A Multidisciplinary Approach [Internet. Mailand: Springer-Verlag, 2011. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9788847018655 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampson JA. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1927;14:422–69. 10.1016/S0002-9378(15)30003-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boussios S, Mikropoulos C, Samartzis E, et al. Wise management of ovarian cancer: on the cutting edge. J Pers Med 2020;10:41. 10.3390/jpm10020041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasvandik S, Samuel K, Peters M, et al. Deep quantitative proteomics reveals extensive metabolic reprogramming and cancer-like changes of ectopic endometriotic stromal cells. J Proteome Res 2016;15:572–84. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samartzis EP, Labidi-Galy SI, Moschetta M, et al. Endometriosis-Associated ovarian carcinomas: insights into pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutic targets-a narrative review. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:1712. 10.21037/atm-20-3022a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prowse AH, Manek S, Varma R, et al. Molecular genetic evidence that endometriosis is a precursor of ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer 2006;119:556–62. 10.1002/ijc.21845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokcu A. Relationship between endometriosis and cancer from current perspective. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;284:1473–9. 10.1007/s00404-011-2047-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munksgaard PS, Blaakaer J. The association between endometriosis and gynecological cancers and breast cancer: a review of epidemiological data. Gynecol Oncol 2011;123:157–63. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javert CT. Pathogenesis of endometriosis based on endometrial homeoplasia, direct extension, exfoliation and implantation, lymphatic and hematogenous metastasis, including five case reports of endometrial tissue in pelvic lymph nodes. Cancer 1949;2:399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beavis AL, Matsuo K, Grubbs BH, et al. Endometriosis in para-aortic lymph nodes during pregnancy: case report and review of literature. Fertil Steril 2011;95:2429.e9–2429.e13. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escobar PF. Lymphatic spread of endometriosis to para-aortic nodes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013;20:741. 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauchlan SC. The secondary Müllerian system. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1972;27:133–46. 10.1097/00006254-197203000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jerman LF, Hey-Cunningham AJ. The role of the lymphatic system in endometriosis: a comprehensive review of the literature. Biol Reprod 2015;92:64. 10.1095/biolreprod.114.124313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noël J-C, Chapron C, Fayt I, et al. Lymph node involvement and lymphovascular invasion in deep infiltrating rectosigmoid endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2008;89:1069–72. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrao MS, Podgaec S, Dias JA, et al. Deeply infiltrating endometriosis affecting the rectum and lymph nodes. Fertil Steril 2006;86:543–7. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tempfer CB, Wenzl R, Horvat R, et al. Lymphatic spread of endometriosis to pelvic sentinel lymph nodes: a prospective clinical study. Fertil Steril 2011;96:692–6. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.06.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]