Abstract

Background

Curricula are reviewed and adapted in response to a perceived need to improve interprofessional collaboration for the benefit of patient care. In 2005, the module Interprofessional Collaboration in Healthcare (IPCIHC) was developed by the Antwerp University Association (AUHA). The program was based upon a concept of five steps to IPCIHC. This educational module aims to help graduates obtain the competence of interprofessional collaborators in health care.

Methods

Over a span of 15 years, the IPCIHC module is evaluated annually by students and provided with feedback by the tutors and steering committee. Data up to 2014 were supplemented with data up to 2019. For the students the same evaluative one-group, post-test design was used to gather data using a structured questionnaire. The tutors’ and students’ feedback was thematically analyzed.

Results

Based upon the results and the contextual changing needs, the program was adjusted. Between 2005 and 2019, a total of 8616 evaluations were received (response rate: 78%). Eighty percent of the respondents indicated through the evaluations that they were convinced of the positive effect of the IPCIHC module on their interprofessional development. Over the years, two more disciplines enrolled into this program and also education programs form the Netherlands.

Conclusions

After 15 years, positive outcomes are showed, and future health professionals have a better understanding of interprofessional learning. Gathering feedback and annually evaluation helped to provide a targeted interprofessional program addressing contextual changes. The challenge remains to keep on educating future healthcare providers in interprofessional collaboration in order to achieve an increase in observable interprofessional behaviour towards other professional groups.

Keywords: collaborate, education, healthcare, interprofessional

Izvleček

Podlaga

Učni načrti se pregledajo in prilagodijo glede na zaznano potrebo po izboljšanju medpoklicnega sodelovanja v korist zdravstvene oskrbe pacientov. Združenje Univerze v Antwerpnu (AUHA) je leta 2005 razvilo modul Medpoklicno sodelovanje v zdravstvenem varstvu (IPCIHC). Ta program je temeljil na konceptu petih korakov za IPCIHC. Cilj tega izobraževalnega modula je diplomantom pomagati pridobiti kompetence medpoklicnega sodelavca v zdravstvenem varstvu.

Metode

Študenti so zadnjih 15 let vsako leto ocenjevali modul IPCIHC, predavatelji in usmerjevalni odbor pa so zagotovili povratne informacije. Podatki do leta 2014 so bili dopolnjeni s podatki do leta 2019. Za študente iz iste skupine za ocenjevanje je bila uporabljena metoda zbiranja podatkov po preskusu s strukturiranim vprašalnikom. Povratne informacije predavateljev in študentov so bile tematsko analizirane.

Rezultati

Program je bil prilagojen na podlagi rezultatov in potreb po kontekstualnih spremembah. Osemdeset odstotkov od skupno 8.616 udeležencev (78-odstotni skupni odziv) med letoma 2005 in 2019 je bilo prepričanih, da IPCIHC pozitivno vpliva na njihov medpoklicni razvoj. V preteklih letih so bili v program vključeni še dve disciplini in izobraževalni programi z Nizozemske.

Zaključki

Po 15 letih so vidni pozitivni rezultati, bodoči zdravstveni delavci pa bolje razumejo medpoklicno učenje. Zbiranje povratnih informacij in letna ocenjevanja so omogočili oblikovanje ciljno usmerjenega medpoklicnega programa, ki obravnava kontekstualne spremembe. Še naprej ostaja izziv nadaljevanje izobraževanja bodočih zdravstvenih delavcev na področju medpoklicnega sodelovanja z namenom povečanja zaznavnega medpoklicnega odnosa do drugih strokovnih skupin.

Ključne besede: sodelovanje, izobraževanje, zdravstveno varstvo, medpoklicno

1. Introduction

Educational modules on interprofessional collaboration (IPC) are developed in response to the perceived need to improve interprofessional collaboration for the benefit of patient care (1). Interprofessional Education (IPE) occurs when two or more professions learn from, about, and with each other regarding effective collaboration and the improvement of health outcomes (2, 3).

The positive influence and effectiveness of an educational intervention by IPE in various disciplines of healthcare is shown in the review of Guraya SY and Barr H (4). They also state that managing the growing number of students registered in each semester for mandatory interprofessional courses requires cohesive efforts by administration and faculty. Organizing and coordinating, scheduling, timetabling and allocating sufficient time, and finding appropriate teaching resources are not easy tasks in order to make interprofessional courses possible in different curricula (4). Adding to these logistic challenges, interprofessional education programs should include opportunities for beneficial contact with students from other professions, and for students to develop a clear understanding of their own profession (5). Over time, national and international policy makers have repeatedly called for the use of IPE to better prepare health and social care learners to enter the workplace as effective collaborators (3, 6, 7). Learning about interprofessionality and learning how to think and act interprofessionally implies offering education in a context that reflects the students’ current or future practices so effective learning can take place (8).

Since the IPCIHC module’s conception in 2005 and since the 2015 evaluation of the first 10 years’ development period, the education context and students’ needs have continued to evolve considerably. The ICPIHC is now an established course and after the development period, this current period pertains to sustaining it and further scaling up. In this subsequent phase, the course has further developed reacting to these changes. This led to the following research questions: a) How did changes in context and students’ needs influence the implementation and scale-up of the program? b) How did the target population evaluate the program in the scale-up phase?

2. Methods

2.1. Evaluation of the module

To gain insight in the needs, strengths, weaknesses, threats and opportunities of the organization as an educational project, the IPCIHC-module used annual evaluations by the students, teachers, departments and faculty to continually refine content, improve process and better integrate the theoretical framework of interprofessional education. With participative observation of the first and last author that were a part of these processes, more in-depth issues could be identified and tackled as necessary. Feedback from the tutors and members of the steering committee were also yearly gathered and used in the developing process. This qualitative information from staff and faculty was not assessed in the first publication of the development phase. In addition, we also used the annual participant evaluation, similarly to the 2015 study to assess how the education objectives were perceived to be reached.

To be able to merge the data from March 2005-2014 with those from 2015 up until March 2019, a singular group post-test design was used to gather data from the participants using the same structured questionnaire as in a previous publication (10). On the last day of the training the questionnaire was offered to all participating students. All participating students were informed about the questionnaire’s aim, the fact that the data would be processed anonymously, and the results could be published.

2.2. Sample

From all the participating education programs for healthcare of the Antwerp University Association (AUHA) all final year students between 2005 and 2019 were included. The students represented over the years the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (University Antwerp), the departments of health and social care of the AP University College Antwerp, the departments of health and social care of the University College Karel-de-Grote Antwerp, the department of dieticians and nutrition of the AP University College Antwerp, and the department of psychology and speech therapy of the Thomas More University College. From 2015 onwards the department of health of the HZ University College of applied sciences of Zeeland (Netherlands) and the Faculty of Pharmaceutical, Biomedical and Veterinary Sciences of the University of Antwerp took part in this project.

2.3. Data collection, instrument and analysis

The data werecollected as in the previous study in 2015 so we could merge the data (10).

The participants evaluated the IPCIHC-module by a written questionnaire based on the evaluation strategy used in Parsell et al. (11) (Table 1). The gathered data from the questionnaire were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Alongside the closed questions (yes or no answer) we also gathered feedback from the tutors at the end of the module. All information was processed anonymously. All written text on the questionnaires, as well as all feedback, that was sent by email as an attachment by the tutors, was analyzed by two members of the steering committee. A thematic analysis was performed on those qualitative data and translated into a SWOT list, to be changed and to be taken into account for the following year’s organization.

Table 1.

Seven closed questions used for the written evaluation (10).

| Seven closed questions used for the written evaluation (10). |

|---|

| 1. Has the course increased your knowledge of the roles and duties of other professional groups? |

| 2. Has the course changed your understanding of how other professional groups work? |

| 3. Has the course changed your attitude towards other professional groups? |

| 4. Do you feel that a course in interprofessional learning will have any effect on your future relationships with other professional groups? |

| 5. Should interprofessional learning be included in your undergraduate course? |

| 6. Do you feel you have a greater understanding about problem solving in teams within healthcare? |

| 7. Do you think a course in interprofessional learning will enable you to work more effectively as a member of a healthcare team? |

3. Results

3.1. Context changes and implementation of scale up

Based upon the gathered data we gained insight into the contextual changes that occurred throughout the years such as internationalization, more participating students and more international participants. This resulted in more attention paid to interprofessional learning, leading to more interest in courses, changes in curricula, more attention on goal-oriented care, and more digital learning environments.

The IPCIHC program reacted to these developments by expanding and adoption. It resulted in a scale-up in different dimensions: a horizontal dimension relating to expanding the number of students, a diversification dimension meaning that new components and educations were added, and an integration dimension referring to stronger theoretical foundations in the methods and practice (12).

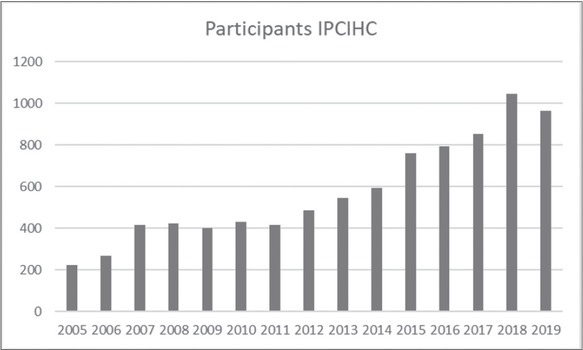

The horizontal scale-up dimension implied growth in the number of participating students per year. Some participating programs joined and obliged their last-year student to participate in contrast to before 2015 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participants of IPCIHC-module from 2005 to 2019.

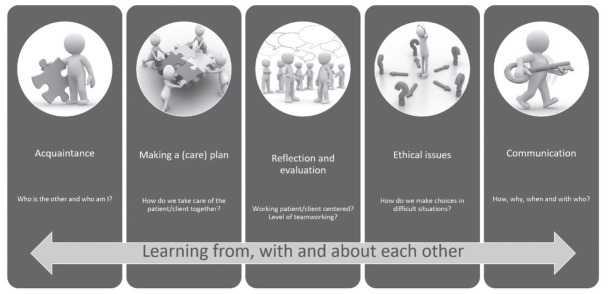

The content dimension was strengthened through elaborating the theoretical and methodological basis. The initial program was based on the model of the competence of the ‘collaborator in healthcare’ (13). Through the years of experience and based on the feedback, a clearer and more appropriate presentation of the interprofessional concept seemed crucial. This resulted in a transparent presentation of the five steps, building bricks, of interprofessional collaboration – (IPCIHC-model) (Figure 2): ‘Acquaintance’, ‘Making a (care) Plan’, ‘Reflection and Evaluation’, ‘Ethical issues’, and ‘Communication’. Based upon this model, we focused on education tools and methods to offer a first experience of getting to know each other and working together from the perspective of professional identity. The aim was to upgrade their level of awareness of what can be expected of theirs and others’ professions and to further develop their interprofessional identity. This has been complemented with a common perspective towards patients, based upon the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF-framework) (14), which allows students to view and consolidate patients’ problems, strengths and potential solutions from various angles into an integrated (interprofessional) care plan. This is the result of cooperation, intense collaboration and co-creation by the various institutes involved.

Figure 2.

The IPCIHC- five steps model to learn to collaborate interprofessionally.

Today’s students choose for exchange programs and so we were motivated to provide a blended program. This development increased students’ flexibility to join the program even though they were not able to participate exactly on the week it was foreseen. Therefore, developing a replacement assignment became an important criterion for tackling also non-foreseen absence. Furthermore, more programs are being offered in English, so IPCIHC has at least two interprofessional teams per year who get the program offered in English. This implies that all documents must be available in two languages (Dutch and English). In the past 5 years we have put much more effort in creating a digital platform to gather all in English written documents necessary for participating in and completing assignments during the IPCIHC-module.

The diversification dimension of scale-up refers to the addition of new education programs and new components to the course. Student diversity has increased through involving students from new disciplines. In total, today seventeen participating educational programs are involved in this IPCIHC-module, from five institutions: medicine, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, nursing, midwifery, nutrition and dietetics, speech therapy, social work, and a bachelor’s in psychology (10). The latest additions include students from pharmacy and social educational care work. In addition, international students (nursing and social work from the Netherlands) were included, which provided the course with an additional intercultural aspect. The changes led to new institutional arrangements and a new working culture, and further increased the richness of participating disciplines in the interprofessional teams.

The duration of the education programs of medicine, midwifery and nursing changed over time. This challenged us logistically in the transition period to host even double cohorts and so double the number of participating students. These changes also implied changes in the curricula. Even though IPCIHC was still included in all curricula for some education programs it was maybe embedded differently in the curriculum and it resulted in other teachers becoming responsible for this course, as well as their appointment in the steering committee. The integration dimension of the scale-up ensured better embedding in the participating institutions’ physical and theoretical environments. The digital transformation comprised students and facilitators working online on portfolios and evaluations. This increased collaboration with the e-campus, which further evolved into the development of digital learning and assessment platforms, a digital safe environment, and more digital courses. This allowed participants to follow courses at their own time and place, facilitating blended learning to take off. An example of the integration of theory is the introduction of the ICF framework into the IPCIHC-module, as a tool to structure collaborative working. Other participating programs were not familiar with this concept and now it is integrated into some of their own courses as well.

3.2. Evaluation of the IPCIHC by the target population

Since 2005, over 8000 students have attended this module, for which all participant evaluations and comments from 2005 up to 2019 were gathered (Figure 3). As in the previous study (10) the evaluation was anonymous and now in total 6330 of 8124 (78% overall response) students have evaluated the module. This is a 6% lower response than the last publication.

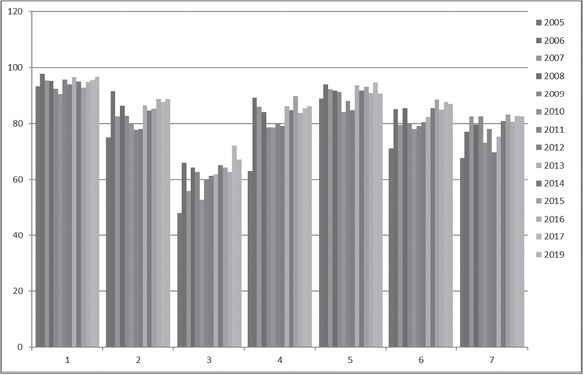

Figure 3.

Percentage of ‘yes’ answers per question per year on the seven closed questions (Total number of participants = 8616) (from 1 to 7 the questions).

Overall, the results are very similar to the previous publication. Ninety percent of all participants indicated that the IPCIHC-module increased their knowledge about the roles and duties of other professional groups. Surprisingly still eighty percent was convinced the IPCIHC-module changed their understanding on how other professional groups work. Attitudes towards other professional groups changed for fewer than 60% of the participants. Also here, in general, the participants commented that they already had a positive attitude before the IPCIHC-module. The percentage of positive scores were maintained between 2014 and 2019. On the fourth question more than 80% answered again ‘yes’. Even after 15 years still 90% of the participants at convinced that interprofessional learning should be included in undergraduate courses. Almost 80% felt greater understanding about problem solving in teams within healthcare. A course in interprofessional learning is thought by the participants to enable them to work more effectively as a member of a healthcare team.

4. Discussion

With this evaluation we aimed to get insight into the contextual adaptations and the evolvement of participant evaluations over 15 years of organizing and evaluating the IPCIHC-module. These insights illustrate how interprofessional learning can be scaled up in response to contextual changes. Challenges can be overcome through flexibility, good collaboration, and negotiations between the participating education programs. Participants appreciate even more the learning effects and the interprofessional experience when they fit well in their learning process. The bases of the theoretical IPCIHC-module was not only the basis of the structure of this educational module, it determined the themes of the module’s content, but above all it is also example of ‘good practice’ in interprofessional collaboration to organize and provide an interprofessional course. So, it was about learning with, from and about one another as participating institutes.

We are very aware of this study’s limitations, as it made use of a short evaluation questionnaire with closed questions. The shortness has, however, also contributed to the high response rate throughout the project’s duration, which is a strength.

The evaluation shows the capacity of the program leadership and participating institutions to adapt the program and the collaboration to the changes in context and need, which allowed for a scale-up in all three dimensions.

It is remarkable that even though the amount and backgrounds of the participants changed over the years, the results confirm that the Antwerp (Belgian) IPCIHC module was evaluated well. The continuous changes in health care, institutions and curricula did not affect appreciation for this interprofessional module.

We can say with caution the structure and system of this module is resistant to many contextual changes. The importance of interprofessional education and the link with competence seem clear from the literature (15, 16, 17). But as an organizing team you have to take contextual changes into account. The five steps to interprofessional collaboration helped to structure the module. These five steps are given content regardless of the context. The learning methods and materials can be changed respecting the theme of the step. The qualitative evaluation of context was valuable for the IPCIHC module’s operational aspects, because it allowed the module’s developers to better understand the influence of context and to adapt content, structure and delivery.

The student evaluation showed that important success factors in the program include getting to know each other as the first step. So also, the steering team takes time and puts effort in getting to know each other as new participating education program. Positive and negative feedback received from the tutors and the participants must always be gathered, analyzed, and taken into account, so program changes are not drastic but targeted. They are being adopted step by step and appreciated by the participating education programs, and the students and tutors thus feel addressed. Educating future healthcare providers in interprofessional collaboration still remains a challenge in order to strengthen observable interprofessional behaviour towards other professional groups. From previous research, we know professionals in practice need more interprofessional education (18, 19).

New challenges crossed our path and resulted in new projects, which will further help scale up the IPCIHC-module. For example, new interprofessional education programs within the international Interreg project were launched and, based upon this, the IPCIHC model (20) helped to decrease the gap of knowledge and training in the interprofessional collaboration competence of healthcare practitioners trained in high schools. We also are validating an interprofessional collaboration tool to scan the level of intensity of interprofessional and interorganizational collaboration in nursing homes (21). It is not enough only to challenge curricula and education programs, but it is necessary to enhance interprofessional collaboration in practice, and to implement more patient-oriented and targeted care. What we organize for students can be translated into what we deliver to patients (9). Nevertheless, still more research is needed to measure the effect on students’ individual levels of interprofessional competence. More comparison of those results can help provide insight into the differences between education programs.

5. Conclusion

All gathered data gave an overview of the content and up-scale of the IPCIHC module’s organization. Over 15 years the evaluation of the interprofessional module has stayed stable. The clear representation of the concept of interprofessional collaboration in five building bricks may be helpful as a framework to gain insight in logistical and contextual challenges.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all participating education programs and participating institutions. Above all, we are very grateful to all tutors, members of the steering comity, and the participating students for their enthusiastic and interactive participation.

Funding Statement

The study was conducted during an educational program so no extra funding was foreseen.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

Ethical approval

As is in the first publication (10) no approval of an ethics committee was required for this study according to the Belgian Law of 7 May 2004 concerning Experiments on the Human Person. Therefore the study does not in any way constitute or involve a ‘test carried out on the human person’ (within the meaning of Article 2, 7° of this Law), but only concerns an assessment of an educational module. All participating students and tutors were informed about the questionnaire and the fact that the data would be processed anonymously.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barr H, Koppel I, Reeves S, Hammick M, Freeth D. Effective interprofessional education: argument, assumption & evidence. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.A definition (CAIPE, 2002). Accessed December 2020 at. https://www.caipe.org/about-us Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education Interprofessional education.

- 3.Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice. Accessed December 2020 at. https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/ World Health Organisation.

- 4.Guraya SY, Barr H. The effectiveness of interprofessional education in healthcare: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2018;34(3):160–5. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong RY, Roberts LD, Brewer M, Flavell H. Quality of contact counts: the development of interprofessional identity in first year students. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;86 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frenk J. The global health system: strengthening national health systems as the next step for global progress. PLoS Med. 2010;7(1):e1000089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, Goldman J, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD000072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reeves S, Fletcher S, Barr H, Birch I, Boet S, Davies N, e al. A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME guide no. 39. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):656–68. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1173663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Amour D, Oandasan I. Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: an emerging concept. J Interprof Care. 2005;19:1:8–20. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsakitzidis G, Timmermans O, Callewaert N, Truijen S, Meulemans H, Van Royen P. Participant evaluation of an education module on interprofessional collaboration for students in healthcare studies. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:188. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0477-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsell G, Spalding R, Bligh J. Shared goals, shared learning: evaluation of a multiprofessional course for undergraduate students. Med Educ. 1998;32(3):304–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Olmen J, Menon S, Poplas Susic A, Ir P, Klipstein-GRobusch K, Wouters E, et al. Scale-up integrated care for diabetes and hypertension in Cambodia, Slovenia and Belgium (SCUBY): a study design for a quasi-experimental multiple case study. Global Health Action. 2020;13(1) doi: 10.1080/16549716.2020.1824382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsakitzidis G, Van Royen P. To learn to collaborate interprofesisonally in health care. Belgium: De boeck - van Inn uitgeverij; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Accessed December 2020. https://www.whofic.nl/familie-van-internationale-classificaties/referentie-classificaties/icf World Health Orgnaisation.

- 15.Barr H, Low H. Interprofessional education in pre-registration courses. CAIPE. Accessed December 2020 at. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/36100398/interprofessional-education-in-pre-registration-courses-general-

- 16.Accessed December 2020 at. http://www.caipe.org.uk/ Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE)

- 17.Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsakitzidis G, Anthierens S, Timmermans O, Truijen S, Meulemans H, Van Royen P. Do not confuse multidisciplinary task management in nursing homes with interprofessional care! Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2017:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S146342361700024X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsakitzidis G, Philips H. Interdisciplinary dialogue. Is there a need for training on working together? Huisarts Nu. 2013;42(6):291–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.European project Zoro. Accessed December 2020 at. https://www.provincieantwerpen.be/aanbod/dese/deis/zorginnovatie-economie-en-arbeidsmarkt/zorgeconomie/europees-project-zoro.html

- 21.Tsakitzidis G. IPSIG-4U project. Accessed December 2020 at. https://www.uantwerpen.be/nl/personeel/giannoula-tsakitzidis/onderzoek/