ABSTRACT

Aim:

Denture stomatitis (DS) is a common inflammatory reaction in denture wearers. The severity of palatal inflammation in DS is believed to be related to Candida colonization. The present study evaluated the presence of Candida at the palatal and the denture surface. The factors associated with DS were also investigated.

Materials and Methods:

Eighty-two denture wearers were evaluated for DS based on Newton’s classification. The samples were collected from palatal mucosa and the denture surface for Candida culture. The predisposing factors associated with DS were also assessed by questionnaire and by oral and dental prosthesis examination.

Results:

Thirty patients showed no signs of DS (36.59%), while 52 patients (63.41%) had DS. Candida was detected in 81.71% of all patients and specifically in 26.83% and 54.88% of non-DS and DS patients, respectively. The proportion of patients with a large amount of Candida at the palatal mucosa in the DS group (40.38%) was higher than in the non-DS group (26.67%) but not significantly different (P > 0.05). The amounts of Candida among the different Newton types also showed no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05). Candida was also detected on the denture surface of the non-DS (34.15%) and DS patients (57.32%). The amounts of Candida on the denture surface between the two groups showed no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). The predisposing factors related to DS included the absence of occlusal rest and poor denture stability (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

In this study, no association between the amount of Candida and DS was found. Mycological examination may be useful for the detection of Candida-induced DS and management. However, further study is required to establish a protocol for antifungal drugs prescription in the treatment of Candida-induced DS among the Newton type.

KEYWORDS: Candida, denture stomatitis, Newton’s classification, palatal inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Denture stomatitis (DS) is a common inflammatory process that predominantly involves the palatal mucosa under dentures. Candida is believed to play a role in palatal inflammation because of its ability to adhere to oral mucosa or under the dentures, resulting in an accumulation of Candida colonies and a biofilm.[1] Predisposing factors such as old age, certain systemic diseases, nighttime denture wearing, the age of the dentures, and smoking have been additionally shown to be involved in DS.[2,3,4] According to Newton’s classification, DS can be classified into three types depending on the severity of the disease: (1) Type 1, a focal inflammation with pinpoint hyperemia; (2) Type 2, diffuse erythema of the mucosa covered by the denture; and (3) Type 3, an inflammatory papillary hyperplasia.[5] Newton’s Type 1 is usually trauma induced, whereas Newton’s Types II and III have multifactorial factors, among which Candida infection is the most important.[6] The treatment of DS often requires antifungal agents or antiseptic mouthwash. In addition, the management of DS includes promoting good oral hygiene and eliminating possible related factors.[7] However, it has been suggested that in most cases of DS, the elimination of denture faults, control of oral hygiene, and discontinuous denture wearing are sufficient treatment and the routine use of antifungal or antiseptic agents is unnecessary.[5]

The relationship between the presence of Candida and DS has been previously investigated. Several studies have reported a significantly greater prevalence and density of Candida species in DS patients compared with those of denture-wearing controls.[8,9] Altarawneh et al. reported that patients with DS had higher amounts of Candida in their saliva and under the dentures than patients without DS. However, the mucosal Candida count on the oral mucosa and cytological hyphae in both the groups were not statistically different.[10] Marinoski et al. found more positive microbiological findings on the palate and tongue of DS patients but with no statistically significant differences compared with the healthy control group.[11] Barbeau et al. showed that yeast presentation on dentures was not related to whether or not the subjects had stomatitis. A higher prevalence of yeast carriers, yeast colony number, and plaque coverage was found on the dentures of subjects with the most extensive inflammation, regardless of the Newton type.[2] Therefore, it remains inconclusive as to whether the number of Candida colonies at the palatal mucosa and denture surface is associated with the Newton type or palatal mucosal conditions. Furthermore, it is not known whether there is any difference between the Candida colony number in DS patients and in denture wearers with no palatal inflammation.

In this study, the presence of Candida was investigated in relation to the palatal mucosa conditions. The amount of Candida under dentures and factors in relation to DS were also studied. The data may help clinicians to provide suitable management for DS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study included 82 patients with upper removable dentures (complete dentures, acrylic partial dentures, and cast partial dentures) who attended the Department of Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine in the Faculty of Dentistry at Srinakharinwirot University in Bangkok, Thailand, from 2017 to 2018. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Research, Faculty of Dentistry, Srinakharinwirot University (Approval number DENTSWU-EC16/2560). All the participants provided written informed consent. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged between 20 and 85 years old; (2) patients had worn upper removable dentures for more than 1 month; and (3) patients did not take any medication that might affect oral bacteria flora, such as antibiotics, antifungals, and corticosteroids or had stopped using the drugs at least 1 month before. The exclusion criteria were patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and autoimmune diseases and those with oral fungal infection.

Data were obtained as follows: first, the patients’ case history was taken and a structured questionnaire for data collection was completed by the operator after consultation with the patients. The data analyzed included the patients’ demographic data (age, gender, and systemic diseases), smoking habit, prosthesis hygiene, the age of the dentures, and nighttime denture wearing. Next, evidence of DS was assessed by an oral medicine specialist in a clinical setting. The type of palatal inflammation was scored using the classification of DS according to Newton’s classification.[12] The severity of palatal inflammation was classified as (1) no DS, no evidence of palatal inflammation; (2) Newton Type I, localized hyperemia at any part of the palatal mucosa in contact with the denture; (3) Newton Type II, diffused erythema without hyperplasia; and (4) Newton Type III, diffuse erythema or generalized erythema with papillary hyperplasia. The dentures were evaluated by direct examination. The data analyzed included the type of denture (complete or partial), the type of denture base (metal or acrylic resin), the denture designs (presence or absence of occlusal rests), and the denture stability. The denture stability was classified as good stability or no stability. The denture stability was defined as the resistance to horizontal forces. The denture was counted as no stability if complete dentures can move 2mm or more in any direction when the denture is manually moved laterally and partial denture can move 1mm or more when unilateral or bilateral forces are applied to the denture base. The presence of occlusal rests of removable partial dentures was counted as stated by the previous studies.[13,14] The data about the patient’s periodontal status and dental caries were also recorded.

The specimen yeasts were collected from the palatal mucosa (the palate-denture contact area) and the surfaces of the dentures of 82 patients using a cotton swab. The samples’ approach involved gently rubbing a sterile cotton swab over the palatal tissue and the denture surface of each patient and then subsequently cultivated in two separate Sabouraud dextrose agars. The specimen yeasts were then incubated under aerobic conditions at 37°C. The number of colonies was counted after 48h and was graded into four groups as modified from Gacon et al.[15] as follows: (1) no yeast (0 colony); (2) small (1–10 colonies); (3) moderate (11–100 colonies); and (4) large (>100 colonies).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics for the demographic characteristics of the studied population were calculated as a percent distribution and mean and standard deviation. Mann–Whitney U-test or Chi-square test was applied for testing the differences in the demographic characteristics between the groups as appropriate. The differences between the amount of Candida colonization and the variables between the DS and non-DS groups and among the Newton types were analyzed by Chi-square test. The associations between DS and the variables were analyzed by bivariate logistic regression, followed by a multivariate logistic regression model for variables with P < 0.25. The age, type of dentures, denture stability, nighttime wearing, and occlusal rest were considered as confounding factors and included in multivariate logistic regression analysis as covariates. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corp, Somers, NY, USA).

RESULTS

In total, 82 patients were included in the study, comprising 57 female patients (69.51%) and 25 male patients (30.49%). Their ages ranged between 21 and 83 years old, with a mean age of 59.65 ± 12.26. Sixty percent of patients in the non-DS group and 34.62% of patients in the DS group had systemic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. All the patients were taking prescribed medicine for their systemic diseases and their conditions were under the supervision of their physicians. The sex, systemic diseases, smoking habit, denture materials, and average age of the dentures between the two groups showed no statistically significant differences (P > 0.05). However, mean age, the type of dentures, the absence of occlusal rest, the denture stability, and nighttime denture-wearing habit were found to be statistically significantly different between the DS and non-DS groups (P < 0.05) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the studied population

| General data | Presence of denture stomatitis (DS group), n (%) | Absence of denture stomatitis (non-DS group), n (%) | Total, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 12 (23.08) | 13 (43.33) | 25 (30.49) | 0.055 |

| Female | 40 (76.92) | 17 (56.67) | 57 (69.51) | |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 57.86±10.79 | 62.7±14.08 | 59.65±12.26 | 0.020 |

| Systemic diseases | ||||

| Healthy | 34 (65.38) | 12 (40.00) | 46 (56.10) | 0.065 |

| Hypertension | 7 (13.46) | 6 (20.00) | 13 (15.85) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 (0.00) | 3 (10.00) | 3 (3.66) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 (9.62) | 3 (10.00) | 8 (9.76) | |

| Others | 6 (11.54) | 6 (20.00) | 12 (14.63) | |

| Smoking habit | ||||

| Yes | 4 (7.69) | 3 (10) | 7 (8.54) | 0.719 |

| No | 48 (92.31) | 27 (90) | 75 (91.46) | |

| Type of dentures | ||||

| Upper complete denture | 6 (11.54) | 9 (30.00) | 15 (18.29) | 0.037 |

| Upper partial denture | 46 (88.46) | 21 (70.00) | 67 (81.71) | |

| Denture materials | ||||

| Acrylic | 38 (73.08) | 17 (56.67) | 55 (67.07) | 0.128 |

| Metal | 14 (26.92) | 13 (43.33) | 27 (32.93) | |

| Occlusal rest* | ||||

| Presence | 13 (28.26) | 13 (61.90) | 26 (38.81) | 0.009 |

| Absence | 33 (71.74) | 8 (38.10) | 41 (61.19) | |

| Stability of dentures | ||||

| Good | 19 (36.54) | 21 (70) | 40 (48.78) | 0.004 |

| No | 33 (63.46) | 9 (30) | 42 (51.22) | |

| Average age of dentures (months), mean±SD | 92.70±91.48 | 60.18±68.82 | 80.56±84.74 | 0.096 |

| Nighttime wearing | ||||

| Yes | 18 (34.62) | 4 (13.33) | 22 (26.83) | 0.036 |

| No | 34 (65.38) | 26 (86.67) | 60 (73.17) |

*Only patients wearing partial dentures were included. DS=Denture stomatitis, SD=Standard deviation

PRESENCE OF CANDIDA AT THE PALATAL MUCOSA AND ON THE DENTURE SURFACES OF THE DENTURE STOMATITIS AND NON-DENTURE STOMATITIS PATIENTS

Seven patients (13.46%) in the DS group and eight patients (26.67%) in the non-DS group had no Candida colonization. Ten patients (19.23%) in the DS group and eight patients (26.67%) in the non-DS group had a small amount of Candida. A moderate number of Candida colonies were found in 14 patients (26.92%) in the DS group and in six patients (20.00%) in the non-DS group. Although the proportion of patients with a large amount of Candida colonization in the DS group (40.38%) was higher than in the non-DS group (26.67%), the amount of Candida colonization between the two groups was not significantly different (P = 0.298) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Amount of Candida colonization at the palatal mucosa and on the denture surface between the denture stomatitis group and the nondenture stomatitis group

| Number of Candida colonies | Palatal mucosa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS group | Non-DS group (n=30, 100%), n (%) | P | ||||

| Newton Type I (n=12, 23.08%), n (%) | Newton Type II (n=19, 36.54%), n (%) | Newton Type III (n=21, 40.38%), n (%) | Total DS (n=52, 100%), n (%) | |||

| No yeast | 0 | 5 (9.62) | 2 (3.85) | 7 (13.46) | 8 (26.67) | 0.298a 0.084b |

| Small number of yeasts | 3 (5.77) | 4 (7.69) | 3 (5.77) | 10 (19.23) | 8 (26.67) | |

| Moderate number of yeasts | 1 (1.92) | 4 (7.69) | 9 (17.30) | 14 (26.92) | 6 (20.00) | |

| Large number of yeasts | 8 (15.38) | 6 (11.54) | 7 (13.46) | 21 (40.38) | 8 (26.67) | |

| Number of Candida colonies | Denture surface | |||||

| DS group | Non-DS group (n=30, 100%), n (%) | P | ||||

| Newton Type I (n=12, 23.08%), n (%) | Newton Type II (n=19, 36.54%), n (%) | Newton Type III (n=21, 40.38%), n (%) | Total DS (n=52, 100%), n (%) | |||

| No yeast | 0 | 2 (3.85) | 3 (5.77) | 5 (9.61) | 2 (6.67) | 0.207 0.821d |

| Small number of yeasts | 2 (3.85) | 1 (1.92) | 2 (3.85) | 5 (9.61) | 4 (13.33) | |

| Moderate number of yeasts | 1 (1.92) | 1 (1.92) | 1 (1.92) | 3 (5.77) | 6 (20.00) | |

| Large number of yeasts | 9 (17.31) | 15 (28.85) | 15 (28.85) | 39 (75.00) | 18 (60.00) | |

aNo significant difference in the number of Candida colonies between the DS and non-DS group at the palatal mucosa, bNo significant difference in the number of Candida colonies among the Newton types at the palatal mucosa, cNo significant difference in the number of Candida colonies between DS and non-DS group on the denture surface, dNo significant difference in the number of Candida colonies among Newton types on the denture surface. DS=Denture stomatitis

According to Newton’s classification, 12 patients (23.08%) in the DS group could be classified as Newton Type I, while 19 patients (36.54%) were classed as Newton Type II, and 21 patients (40.38%) were Newton Type III. The Candida colonization varied from a small amount to a large amount and was detected in all the Newton’s types [Table 2]. There was no relationship between the amount of Candida detection and Newton’s classification (P = 0.084). The data implied that the amount of Candida was not necessarily associated with the severity of palatal inflammation, based on Newton’s classification.

When assessing the number of Candida at the denture surface, 47 patients (90.38%) in the DS group and 28 patients (93.33%) in the non-DS group showed positive Candida detection at the denture surface, respectively. About 1%–20% of patients in the DS and non-DS groups had a small-to-moderate amount of Candida colonization. Most patients showed a large amount of Candida colonization, i.e., 75% in the DS group and 60% in the non-DS group [Table 2]. There was no difference in the number of Candida colonies at the denture surface between the DS and non-DS groups (P = 0.207).

In addition, a large amount of Candida colonization on the denture surface was detected in patients with Newton Type II (28.85%) and III (28.85%). Unexpectedly, most patients with Newton Type I also showed a large amount of Candida colonization (17.31%), as shown in [Table 2]. There was no difference in the amount of Candida colonization on the denture surface based on Newton’s classification (P = 0.821). These results suggested that the amount of Candida on the denture surface was not associated with the Newton’s classification or the severity of palatal inflammation.

PRESENCE OF CANDIDA AT THE PALATAL MUCOSA AND ON THE DENTURE SURFACES OF THE DENTURE STOMATITIS AND NON-DENTURE STOMATITIS PATIENTS CATEGORIZED BY THE DENTURE CONDITION

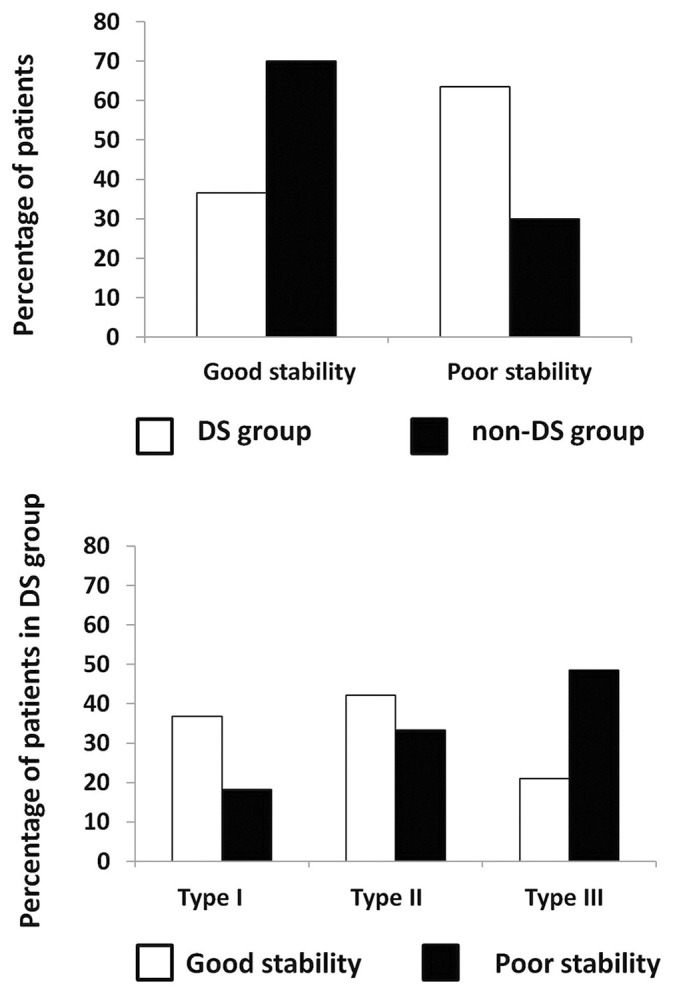

Nineteen patients (36.54%) in the DS group and 21 patients (70.0%) in the non-DS group showed good denture stability. Thirty-three patients (63.46%) in the DS group and 9 patients (30.00%) in the non-DS group had poor denture stability [Figure 1A]. The percentage of patients with poor denture stability was higher in the DS group than in the non-DS group (P = 0.004).

Figure 1.

(A) Percentage distribution of patients according to denture stability. (B) Percentage of denture stomatitis patients with good or poor denture stability according to Newton’s classification. DS = Denture stomatitis

Regarding the relationship between the denture status and Newton’s classification, the highest percentage of DS patients with good denture stability was found in Newton Type I. Besides, most DS patients with Newton Type III had poor denture stability, as shown in [Figure 1B]. There was no difference between the number of patients with good-to-poor denture stability among the Newton types (P = 0.064). In addition, the amount of Candida colonization at the palatal aspect and on the denture surface was not associated with the denture conditions in both the groups (P > 0.05) [Table 3]. These results suggested that the dental denture stability was related to DS; however, the amount of Candida colonization was not associated with the denture stability.

Table 3.

Number of Candida colonies at the palatal mucosa and on the denture surface of the denture stomatitis group and the nondenture stomatitis group categorized by the denture condition

| Number of Candida colonies | Denture stability in the DS group (n=52, 100%), n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palatal mucosa | Denture surface | |||||

| Yes (n=19, 36.54%), n (%) | No (n=33, 63.46%), n (%) | P | Yes (n=19, 36.54%), n (%) | No (n=33, 63.46%), n (%) | P | |

| No yeast | 3 (5.77) | 4 (7.69) | 0.591 | 3 (5.77) | 2 (3.85) | 0.400 |

| Small number of yeasts | 4 (7.69) | 6 (11.54) | 3 (5.77) | 2 (3.85) | ||

| Moderate number of yeasts | 3 (5.77) | 11 (21.15) | 1 (1.92) | 2 (3.85) | ||

| Large number of yeasts | 9 (17.31) | 12 (23.08) | 12 (23.08) | 27 (51.92) | ||

| Number of Candida colonies | Denture stability in the non-DS group (n=30, 100%) | |||||

| Palatal mucosa | Denture surface | |||||

| Yes (n=21, 70.00%), n (%) | No (n=9, 30.00%), n (%) | P | Yes (n=21, 70.00%), n (%) | No (n=9, 30.00%), n (%) | P | |

| No yeast | 6 (20.00) | 2 (6.67) | 0.933 | 1 (3.33) | 1 (3.33) | 0.794 |

| Small number of yeasts | 5 (16.67) | 3 (10.00) | 3 (10.00) | 1 (3.33) | ||

| Moderate number of yeasts | 4 (13.33) | 2 (6.67) | 5 (16.67) | 1 (3.33) | ||

| Large number of yeasts | 6 (20.00) | 2 (6.67) | 12 (40.00) | 6 (20.00) | ||

DS=Denture stomatitis

FACTORS PREDISPOSING TO DENTURE STOMATITIS

Predisposing factors that may influence the occurrence of DS including sex, age of patients, systemic diseases, smoking status, denture design, area of missing teeth, denture materials, denture stability, nighttime denture wearing, age of dentures, denture hygiene, periodontal status, and dental caries were assessed. At the bivariate level, the results showed that age of patients 40–59 years old (P = 0.014, odds ratio [OR] = 3.704), age of patients ≥60 years old (P = 0.019, OR = 0.312), patients with systemic diseases (P = 0.028, OR = 2.833), type of dentures (P = 0.043, OR = 3.286), absence of occlusal rest (P = 0.011, OR = 0.242), poor denture stability (P = 0.004, OR = 0.247), nighttime denture wearing (P = 0.043, OR = 3.441), dentures older than 4 years old (P = 0.007, OR = 3.733), and dentures older than 5 years old (P = 0.020, OR = 3.286) had a significantly greater risk of DS (P < 0.05). However, in the final multivariate logistic regression model, only poor denture stability (P = 0.031, Adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.252) and absence of occlusal rest (P = 0.034, AOR = 0.296) significantly predicted the DS, as shown in [Table 4].

Table 4.

Predisposition factors associated with denture stomatitis

| Factors (n; %) | Presence of denture stomatitis (DS group), n (%) | Absence of denture stomatitis (non-DS group), n (%) | Bivariate logistic regression analysis (P, OR, 95% CI) | Multivariate logistic regression analysisa (P, AOR, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | ||||

| Yes | 40 (76.92) | 17 (56.67) | 0.058, 0.392, 0.149-1.033 | 0.109, 0.363, 0.105-1.255 |

| No | 12 (23.08) | 13 (43.33) | ||

| Age of patients (years) | ||||

| 20-39 | ||||

| Yes | 3 (5.77) | 2 (6.67) | 0.870, 0.857, 0.135-5.443 | |

| No | 49 (94.23) | 28 (93.33) | ||

| 40-59 | ||||

| Yes | 25 (48.08) | 6 (20.00) | 0.014, 3.704, 1.300-10.552 | 0.473, 0.393, 0.031-5.030 |

| No | 27 (51.92) | 24 (80.00) | ||

| ≥60 | ||||

| Yes | 24 (46.15) | 22 (73.33) | 0.019, 0.312, 0.117-0.827 | |

| No | 28 (53.85) | 8 (26.67) | ||

| Systemic diseases | ||||

| Yes | 18 (34.62) | 18 (60.00) | 0.028, 2.833, 1.121-7.162 | 0.076, 3.002, 0.890-10.123 |

| No | 34 (65.38) | 12 (40.00) | ||

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 4 (7.69) | 3 (10.00) | 0.719, 0.750, 0.156-3.603 | |

| No | 48 (92.31) | 27 (90.00) | ||

| Type of dentures | ||||

| Upper complete denture | 6 (11.54) | 9 (30.00) | 0.043, 3.286, 1.035-10.427 | 0.122, 3.373, 0.722-15.749 |

| Upper partial denture | 46 (88.46) | 21 (70.00) | ||

| Free end partial denture* | ||||

| Yes | 11 (23.91) | 7 (33.33) | 0.422, 1.591, 0.513-4.936 | |

| No | 35 (76.09) | 14 (66.67) | ||

| Occlusal rest* | ||||

| Presence | 13 (28.26) | 13 (61.90) | 0.011, 0.242, 0.082-0.721 | 0.034, 0.296, 0.096-0.912 |

| Absence | 33 (71.74) | 8 (38.10) | ||

| Area of missing teeth* | ||||

| Anterior teeth | ||||

| Yes | 16 (34.78) | 7 (33.33) | 0.908, 1.067, 0.358-3.177 | |

| No | 30 (65.22) | 14 (66.67) | ||

| Posterior teeth | ||||

| Yes | 8 (17.39) | 3 (14.29) | 0.751, 1.263, 0.299-5.334 | |

| No | 38 (82.61) | 18 (85.71) | ||

| Anterior and posterior teeth | ||||

| Yes | 22 (47.83) | 11 (52.38) | 0.730, 0.833, 0.296-2.342 | |

| No | 24 (52.17) | 10 (47.62) | ||

| Acrylic dentures | ||||

| Yes | 38 (73.08) | 17 (56.67) | 0.131, 2.076, 0.805-5.351 | 0.461, 1.593, 0.462-5.490 |

| No | 14 (26.92) | 13 (43.33) | ||

| Poor denture stability | ||||

| Yes | 33 (63.46) | 9 (30) | 0.004, 0.247, 0.094-0.647 | 0.031, 0.252, 0.072-0.882 |

| No | 19 (36.54) | 21 (70) | ||

| Age of denture (years) | ||||

| Age of dentures >3 | ||||

| Yes | 34 (65.38) | 14 (46.67) | 0.100, 2.159, 0.863-5.041 | |

| No | 18 (34.62) | 16 (53.33) | ||

| Age of dentures >4 | ||||

| Yes | 32 (61.54) | 9 (30.00) | 0.007, 3.733, 1.429-9.752 | 0.055, 0.298, 0.086-1.028 |

| No | 20 (38.46) | 21 (70.00) | ||

| Age of dentures >5 | ||||

| Yes | 26 (50) | 7 (23.33) | 0.020, 3.286, 1.202-8.982 | |

| No | 26 (50) | 23 (76.67) | ||

| Nighttime denture wearing | ||||

| Yes | 18 (34.62) | 4 (13.33) | 0.043, 3.441, 1.039-11.399 | 0.392, 1.929, 0.428-8.698 |

| No | 34 (65.38) | 26 (86.67) | ||

| Irregular cleaning | ||||

| Yes | 1 (1.92) | 2 (6.67) | 0.300, 3.643, 0.316-41.976 | |

| No | 61 (98.08) | 28 (93.33) | ||

| Cleaning method | ||||

| Toothbrush only | ||||

| Yes | 12 (23.08) | 9 (30.00) | 0.490, 0.700, 0.254-1.927 | |

| No | 40 (76.92) | 21 (70.00) | ||

| Toothbrush with chemical products | ||||

| Yes | 10 (19.23) | 7 (23.33) | 0.659, 0.782, 0.263-2.330 | |

| No | 42 (80.77) | 23 (76.67) | ||

| Toothbrush with toothpaste | ||||

| Yes | 30 (57.69) | 14 (46.67) | 0.336, 1.558, 0.631-3.848 | |

| No | 22 (42.31) | 16 (53.33) | ||

| Gingival diseases* | ||||

| Yes | 23 (50.00) | 10 (47.62) | 0.857, 1.100, 0.391-3.091 | |

| No | 23 (50.00) | 11 (52.38) | ||

| Periodontal diseases* | ||||

| Yes | 17 (36.96) | 3 (14.29) | 0.070, 3.517, 0.902-13.718 | 0.296, 2.229, 0.496-10.025 |

| No | 29 (63.04) | 18 (85.71) | ||

| Dental caries* | ||||

| Yes | 31 (67.39) | 10 (47.62) | 0.127, 2.273, 0.791-6.530 | 0.511, 1.490, 0.454-4.896 |

| No | 15 (32.61) | 11 (52.38) |

*Only patients wearing partial dentures were included, aOdd ratio adjusted for sex, age of patients≥40 years, systemic diseases, type of dentures, acrylic dentures, poor denture stability, age of denture>4 years, nighttime denture wearing, occlusal rest, periodontal diseases, dental caries. DS=Denture stomatitis, OR=Odds ratio, CI=Confidence interval, AOR=Adjusted odds ratio

DISCUSSION

DS is an inflammatory process that involves the palatal mucosa and dentures. It exhibits a multifactorial etiology. Various factors including trauma caused by ill-fitting dentures, poor denture hygiene, nighttime wearing of dentures, accumulation of denture plaque, and bacterial and fungal infections have been reported to be involved in the disease.[4,7] It is known that the presence of Candida in denture plaque is one of the most important factors in the development of DS.[16] Although Candida has been shown to be associated with DS, no conclusive study has confirmed the amount of Candida on palatal tissue or on denture surfaces, according to Newton’s classification. Newton Type I is believed to be related to trauma caused by ill-fitting dentures and does not require an antifungal prescription, while antifungal drugs are given to patients with Newton Types II and III.[17,18] Therefore, data on Candida colonization at the palatal mucosa and on the tissue surface of dentures in relation to Newton’s classification would be informative for clinicians for DS management.

Previous studies have reported Candida colonization at the palatal mucosa of non-DS subjects in 45%–53% of cases.[15,19] The current study showed the presence of Candida colonization at the palatal mucosa, found in both the DS and non-DS groups at rates of 54.88% and 26.83%, respectively. The number of Candida colonies was not related to the severity of palatal inflammation according to Newton’s classification [Table 2]. This was also observed by Gauch et al., who showed that the colonization of Candida at the palatal mucosa was not associated with the severity of the palatal inflammation. They reported 36.11%, 22.22%, and 13.88% cases of Candida colonization in DS patients with Newton Types I, II, and III, respectively.[20] These data suggest that the clinical presentation of mild palatal inflammation can be related to a high percentage of Candida detection. Future clinical studies to evaluate effects of antifungal drug on the different types of DS maybe helpful in establishing a protocol for DS management.

When assessing the amount of Candida colonization on the denture surface, we observed that the number of Candida colonies on the denture surface was not associated with DS or the Newton type. Previous studies also reported that there was no difference between the amount of Candida detected in patients with and without DS.[21] In contrast, Barbeau et al. found that the presence of yeast on dentures was increased in Newton Type III compared with Newton Types I and II. They suggested that the amount of yeast under the dentures was probably related to an extensive inflammation in DS.[2] The possible explanation for the different results among studies could be that the various factors including denture condition, denture materials, the age of the dentures, and denture hygiene related to the studied population in each study can affect the amount of Candida colonization on the denture surface.

Several studies reported that sex, age of patients, systemic diseases, smoking, denture materials, poor denture stability, nighttime wearing, and the age of the dentures play a role in the occurrence of DS.[22,23,24,25] Among the predisposing factors that were evaluated in this study, only poor denture stability and the absence of occlusal rest were predicted to DS (P < 0.05). DS is multifactorial in nature, with trauma could act as a factor that favors the colonization of the yeast. The trauma may originate from poor denture stability. Prior studies have shown an increase in Candida colonization in patients with poorly fitting dentures.[23,26] Furthermore, in this study, the absence of occlusal rest was also related to DS (P < 0.05). The pressure distribution on the residual ridge beneath the removable partial denture base was shown to be dependent on the occlusal rest designs.[13] It could be that the absence of occlusal rest affected the pressure distribution pattern beneath the denture base and probably increased risk of trauma to the denture bearing area.

We found no significant relationship between DS and classic risk factors such as the age of dentures and nighttime wearing. The possible explanation could be that the sample size in this study was small. It could affect the power to detect weaker associations. While this study provides useful data regarding the factors associated with DS, the limitation of this study is that all factors related to DS cannot be included. These factors comprise the nutritional status, alcohol consumption, dental biofilm accumulation, hyposalivation, and decrease of salivary pH. Therefore, it would be beneficial to address these factors in the further study.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, a large amount of Candida colonization at the palatal mucosa was found in a higher proportion of the DS group than in the non-DS group. However, the association was not statistically significant. These data suggest that the degree of palatal inflammation may not be necessarily related to the amount of Candida detection in removable denture wearers. Therefore, mycological examination may be useful for the detection of Candida-induced DS and management. However, further study is required to establish a protocol for the prescription of antifungal drugs in the treatment of Candida-induced DS among the Newton type.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

This research was supported by the Faculty of Dentistry, Srinakharinwirot University (2017).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

PT and PJ were involved in study conception, data collection, data acquisition and analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

ETHICAL POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD STATEMENT

The research project was approved by the Ethical Committee for Research in Human Subjects at Srinakharinwirot University, no. DENTSWU-EC16/2560.

PATIENT DECLARATION OF CONSENT

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data set used in the current study is available on request from Pimporn Jirawechwongsakul/email: pimpornr@g.swu.ac.th

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Ornuma Charoensuk for advice on statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramage G, Coco B, Sherry L, Bagg J, Lappin DF. In vitro Candida albicans biofilm induced proteinase activity and SAP8 expression correlates with in vivo denture stomatitis severity. Mycopathologia. 2012;174:11–9. doi: 10.1007/s11046-012-9522-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbeau J, Seguin J, Goulet JP, de Koninck L, Avon SL, Lalonde B, et al. Reassessing the presence of Candida albicans in denture-related stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:51–9. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shulman JD, Rivera-Hidalgo F, Beach MM. Risk factors associated with denture stomatitis in the United States. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:340–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gendreau L, Loewy ZG. Epidemiology and etiology of denture stomatitis. J Prosthodont. 2011;20:251–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2011.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arendorf TM, Walker DM. Denture stomatitis: A review. J Oral Rehabil. 1987;14:217–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1987.tb00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naik AV, Pai RC. A study of factors contributing to denture stomatitis in a north Indian community. Int J Dent. 2011;2011:589064. doi: 10.1155/2011/589064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webb BC, Thomas CJ, Willcox MD, Harty DW, Knox KW. Candida-associated denture stomatitis. Aetiology and management: A review. Part 3. Treatment of oral candidosis. Aust Dent J. 1998;43:244–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1998.tb00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budtz-Jorgensen E, Theilade E, Theilade J. Quantitative relationship between yeast and bacteria in denture-induced stomatitis. Scand J Dent Res. 1983;91:134–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1983.tb00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arendorf TM, Walker DM. Oral candidal populations in health and disease. Br Dent J. 1979;147:267–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4804344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altarawneh S, Bencharit S, Mendoza L, Curran A, Barrow D, Barros S, et al. Clinical and histological findings of denture stomatitis as related to intraoral colonization patterns of Candida albicans, salivary flow, and dry mouth. J Prosthodont. 2013;22:13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2012.00906.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marinoski J, Bokor-Bratic M, Cankovic M. Is denture stomatitis always related with candida infection? A case control study. Med Glas (Zenica) 2014;11:379–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newton AV. Denture sore mouth: A possible etiology. Br Dent J. 1962;112:357–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suenaga H, Kubo K, Hosokawa R, Kuriyagawa T, Sasaki K. Effects of occlusal rest design on pressure distribution beneath the denture base of a distal extension removable partial denture-an in vivo study. Int J Prosthodont. 2014;27:469–71. doi: 10.11607/ijp.3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson VJ. Acrylic partial dentures-interim or permanent prostheses? SADJ. 2009;64:6–8, 40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gacon I, Loster JE, Wieczorek A. Relationship between oral hygiene and fungal growth in patients: Users of an acrylic denture without signs of inflammatory process. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1297–302. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S193685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Susewind S, Lang R, Hahnel S. Biofilm formation and Candida albicans morphology on the surface of denture base materials. Mycoses. 2015;58:719–27. doi: 10.1111/myc.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turrell AJ. Aetiology of inflamed upper denture-bearing tissues. Br Dent J. 1966;120:542–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Budtz-Jorgensen E. The significance of Candida albicans in denture stomatitis. Scand J Dent Res. 1974;82:151–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1974.tb00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Čanković M, Bokor-Bratić M, Marinoski J, Stojanović D. Prevalence and possible predictors of the occurence of denture stomatitis in patients older than 60 years. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2017;74:311–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gauch LM, Pedrosa SS, Silveira-Gomes F, Esteves RA, Marques-da-Silva SH. Isolation of Candida spp. from denture-related stomatitis in Para, Brazil. Braz J Microbiol. 2018;49:148–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emami E, de Grandmont P, Rompre PH, Barbeau J, Pan S, Feine JS. Favoring trauma as an etiological factor in denture stomatitis. J Dent Res. 2008;87:440–4. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gleiznys A, Zdanaviciene E, Zilinskas J. Candida albicans importance to denture wearers. A literature review. Stomatologija. 2015;17:54–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salerno C, Pascale M, Contaldo M, Esposito V, Busciolano M, Milillo L, et al. Candida-associated denture stomatitis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16:e139–43. doi: 10.4317/medoral.16.e139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turker SB, Sener ID, Kocak A, Yilmaz S, Ozkan YK. Factors triggering the oral mucosal lesions by complete dentures. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51:100–4. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coelho CM, Sousa YT, Dare AM. Denture-related oral mucosal lesions in a Brazilian school of dentistry. J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31:135–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2004.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sampaio-Maia B, Figueiral MH, Sousa-Rodrigues P, Fernandes MH, Scully C. The effect of denture adhesives on Candida albicans growth in vitro. Gerodontology. 2012;29:348–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data set used in the current study is available on request from Pimporn Jirawechwongsakul/email: pimpornr@g.swu.ac.th