Abstract

The majority of healthcare professionals regularly witness fragility, suffering, pain and death in their professional lives. Such experiences may increase the risk of burnout and compassion fatigue, especially if they are without self-awareness and a healthy work environment. Acquiring a deeper understanding of vulnerability inherent to their professional work will be of crucial importance to face these risks. From a relational ethics perspective, the role of the team is critical in the development of professional values which can help to cope with the inherent vulnerability of healthcare professionals. The focus of this paper is the role of Communities of Practice as a source of resilience, since they can create a reflective space for recognising and sharing their experiences of vulnerability that arises as part of their work. This shared knowledge can be a source of strength while simultaneously increasing the confidence and resilience of the healthcare team.

Keywords: professional - professional relationship, interests of health personnel/institutions, history of health ethics/bioethics, ethics

Introduction

Vulnerability is a complex and thought-provoking concept. In a broad sense, there are opposing theoretical approaches on the conception of vulnerability, especially in bioethics, which may result in perceiving it as a largely opaque term. As a result, there is a huge controversy in bioethics and social sciences about this concept.

In this paper we understand vulnerability as a universal, inherent human condition.1 This essential human condition is an important element in bioethics, as well as in the core of healthcare relationships.2 In this context and following the theoretical framework of vulnerability theory (VT), we understand vulnerability as ‘the characteristic that positions us in relation to each other as human beings and also suggests a relationship of responsibility between the state and their institutions and the individual’.3 In the context of healthcare, professionals regularly witness the fragility, suffering, pain and death of others more commonly than most people do in daily life. In addition to witnessing, health professionals may also experience vulnerability as pain and suffering in response to the limits of and uncertainty associated with healthcare. Navigating the differing values of patients, their family and the healthcare team may also lead to distress and a sense of helplessness in caring for complex patients and supporting their families. These factors, among others, may increase healthcare professionals’ risk of burnout and compassion fatigue, when not paired with self-awareness, self-compassion and a healthy work environment.4 5 Each day healthcare professionals interact with human health and illness and high levels of uncertainty: ‘While caring for patients and their families, healthcare professionals share and reflect on the joys and sorrows that accompany these interactions. In many ways, they are suffering too’.6 Thus, acquiring a deeper understanding of vulnerability inherent to health professional work is of crucial importance to face these risks, attending to professionals’ mental health. Not recognising the professionals’ vulnerability may come at a cost for healthcare staff, patients and their families and society at larger.

The recognition of vulnerability has beneficial elements that require greater attention.7 8 For instance, vulnerability is associated with an inherent openness to the world that supports growth and flourishing. Allowing ourselves to be interdependent, recognising and accepting our vulnerability, is a precondition for creativity. Fineman8 indicates that our vulnerability presents opportunities for innovation and growth, creativity and fulfilment, since it promotes relationship formation. We argue that through the recognition and acceptance of our shared vulnerability, better relationships can be built within the professional sphere which may support resilience. For this purpose, it is critical to focus on the relationship between vulnerability and resilience in healthcare settings.

In this paper, we aim to explore the relationship between vulnerability and resilience in the framework of Communities of Practice (CoP). We analyse CoP from a relational ethics perspective,9 assuming that the role of the team is critical in the development of professional values. An earlier project identified the central elements of relational ethics as engagement, mutual respect, embodied knowledge, uncertainty/vulnerability and attention to an interdependent environment.9 We focus on the paradox that vulnerability is an essential characteristic to building resilience in healthcare teams. One way that has been developed to understand how vulnerability can be transformed into a strength is to train for resilience, seeking to improve the psychosocial functioning of members of a therapeutic community.10 We focus on how a CoP in healthcare team can be an essential element on building resilience.

We argue that CoP may be a source of resilience, through the creation of a reflective space for recognising and sharing experiences of vulnerability that arise as part of CoP members’ work.11 This shared knowledge can be a source of strength and benefit to increase the confidence and resilience of the healthcare team and its individual members. Our assumption is that resilience can be fostered within the professional team through ethical values and strategies that arise from shared practical wisdom.

Focusing on CoP, we maintain that a relational turn is at the heart of professionalism. Relationships throughout the healthcare field have profound effects on healthcare professionals as well as on the patients and their families. Relationship-focused care brings with it potential emotional demands and stressors that themselves need careful attention. This set of concerns refers to how daily work can undermine the personality, the mood and well-being of professionals and should of necessity be taken into account in professionalism reflections. In this regard, we recommend that a deeper understanding of vulnerability within healthcare relationships can be of great value to healthcare practice and education.

For our purpose, we will start with a brief introduction to VT and to the understanding of vulnerability as a human condition, indicating why this recognition of our vulnerability is important in healthcare. Next, we will continue with an analysis of the relationship between vulnerability and resilience, linking these two concepts with the relational ethics framework. This analysis will allow us to introduce the concept of CoP, and to explain and analyse the reasons and characteristics why CoP can improve resilience within the healthcare teamwork. Finally, we will conclude with some important aspects to promote CoP in healthcare.

Understanding vulnerability as a human condition

Over the last years, the concept of vulnerability in social sciences as well as in healthcare and bioethics, has been increasingly explored in the literature. In philosophy, this term has long been ignored. Some of the reasons for this under-theorisation can be the individualistic ethics predominating in Western societies; disregard for the importance of the body, and a focus on rationalist philosophy, at the expense of feeling or emotions.12 Apart from the work of Robert Goodin Protecting the Vulnerable,13 it has not been until the most recent years that a greater interest in this concept has been aroused. In the field of ethics, it has been mainly feminist philosophers who have reflected more broadly on it. From this perspective, vulnerability has been considered as a constitutive and fundamental feature of the human condition. In the core of the ethics of care,14–20 authors have highlighted the importance of human interdependence and links. Especially during the last two decades, a broader interest in the concept of vulnerability has occurred in bioethics.21 Florencia Luna,22–25 for example, has deeply explored vulnerability in the field of research ethics, while Mackenzie et al 26 have tried to clarify the concept through the development of a taxonomy of vulnerability. Undoubtedly, Henk ten Have21 has conducted an indispensable research to comprehend how this concept has been understood in bioethics, through the different conceptions and philosophical approaches to vulnerability. However, the vulnerability concept retains some opacity, and there is a controversy about its meaning and the way to understand it in bioethics and social sciences.

In general terms, there are two principal ways of thinking about vulnerability that have been developed in ethics. The first one is a group of approaches that considers vulnerability as a contingent or situational characteristic of being human. This approach emphasises different forms of inequality, dependency, basic needs and deprivation of liberties. These social, economical and political aspects make some people more vulnerable than others. The other main approaches are those which understand vulnerability as an ontological, anthropological or universal condition. This conception is linked to the possibility of suffering that is inherent to human beings. In these approaches, vulnerability is linked to being fragile, susceptible to damage and suffering and is an ontological, anthropological, inherent and shared condition for all human beings. These perspectives consider vulnerability in relation to the fact of our inherent interdependency.

We argue that it is necessary to deeply face the notion of shared and inherent vulnerability within the healthcare field. Reflections on the universal notion of vulnerability in philosophy have been guided by Levinas,27 28 MacIntyre,29 Nusbaum,30 Butler,31 32 Ricoeur,33 Turner,34 Fineman1 3 8 and Pelluchon,35 among others. The common feature of all these philosophical approaches on the concept of vulnerability is that all of them emphasise that being vulnerable is being fragile, susceptible to damage and suffering and it is an ontological, inherent, shared condition. Emmanuel Levinas’ ethics of alterity can be considered the most radical approach to universal vulnerability. For Levinas,27 the relationship that arises in the ethical encounter with the Other, who is vulnerable, is given in the face-to-face encounter. It is an asymmetrical relationship because the self must respond to the Other’s demands. This implies that one (the self) has to assume an asymmetrical responsibility for the life of the other person that is in front of one.

Although there are numerous theoretical approaches to the concept of vulnerability that have been developed especially in recent years, in this paper we conceive vulnerability exclusively within the framework of Martha Fineman's vulnerability theory (VT). We believe that this theoretical approach can provide analytical tools to examine different situations of damage that people suffer or may suffer in the context of healthcare, and to guide healthcare professionals to acquire strategies to overcome it.

VT conceives vulnerability as an unavoidable human condition: we are all vulnerable. This universal vulnerability is an ontological condition of our humanity. Vulnerability is universal and constant as our exposure to the world. Within VT, as Fineman pointed out, ‘undeniably universal, human vulnerability is also particular: it is experienced uniquely by each of us and this experience is greatly influenced by the quality and quantity of resources we possess or can command’.1 At the same time, VT emphasises the fact that vulnerability is not a particular moment in human life but constant across our life course. VT thus focuses on a life course perspective, which means that the institutional support claimed is necessary along the person's life. Highlighting vulnerability as necessary to the human condition, the focus is not on the individual level, but on social responsibility. VT offers a reflection on the role of the social institutions (for our purpose, healthcare institutions) and relationships in which our social identities are formed and enforced.36

As Fineman3 maintains, ‘while all human beings stand in a position of constant vulnerability, we are individually positioned differently,’ but this does not mean that there are different kinds of vulnerability. Thus, Fineman refuses to only apply the term vulnerability to specific groups. As she argues, ‘this targeted group approach to the idea of vulnerability ignores its universality and inappropriately constructs relationships of difference and distance between individuals and groups within society’.8 The nature of human vulnerability constitutes the basis for the social justice claim that the state institutions, such healthcare ones, must be responsible to supporting all patients suffering from health and mental health conditions. We are all inevitably dependent on the cooperation of others, we are involved in networks of relationships. It is our own vulnerability, fragility and dependence on others that lead us to develop links with others.37 Consequently, vulnerability is inherently a ‘relational’ term that concerns the relation between the person or a group of persons and the circumstances or the context.23

In addition, VT conceives that vulnerability is not merely a negative condition; on the contrary, vulnerability can provide positive or negative results.8 Vulnerability is generative because it presents opportunities for innovation and growth at the core of relationships. The positive aspects of vulnerability can ameliorate experiences of isolation and exclusion: it makes us reach out to others, form relationships and build institutions.8 Vulnerability challenges the modern illusion of self-sufficiency and allows us to discover and invent life together. We consider that from the viewpoint of healthcare work, this generative character of vulnerability should be further explored, because it encompasses a huge potential to improve relationships in this field. The shared vulnerability at the workplace can provide an opportunity ‘to design and implement interprofessional approaches that can improve resilience among teams of co-workers’.38 But first, vulnerability must be accepted and not ignored.8

The relationship between vulnerability and resilience

Historically, resilience emerged in the context of disaster prevention, and it was understood as the capacity for individuals or systems to manage and recover from a disturbance. It has been transferred as a concept from the natural and physical sciences into the social sciences and public policy.39 The American Psychological Association defines resilience as ‘the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or even significant sources of stress’.40 This definition does not reflect the complexity of resilience, because determinants of resilience include biological, psychological, social and cultural aspects in interaction to respond to stressful experiences.41 Resilience is a continuum that may be present to differing degrees across multiple domains of life.42 As Southwick et al 41 maintain, ‘rather than spending the vast majority of their time and energy examining the negative consequences of trauma, clinicians and researchers can learn to simultaneously evaluate and teach methods to enhance resilience’.

As well as vulnerability, we understand resilience in terms of the VT framework. In this framework, resilience is the remedy for vulnerability, even if it is an incomplete remedy: ‘although nothing can completely mitigate vulnerability, resilience is what provides an individual with the means and ability to recover from harm, setbacks and the misfortunes that affect her or his life’.43 The definition calls for a more relational understanding of resilience, within a social-ecological framework.44 Resilience is not a static, discrete quality within individuals. It is only made manifest in interaction with the environment, within and through institutions and relationships. The concept of vulnerability as our shared condition leads us to focus on the state and institutional responsibility for providing resources designed to foster resilience. While vulnerability is a constant reality, what is different is the resources we have to deal with it. Because we cannot be invulnerable, the partial solution to our vulnerability is resilience. The focus, then, is not on the intrinsic characteristics of a person or a group, but it is in their resilience in interchange with the demands of the environment. More importantly, this resilience is not a personal choice, but it is dependent on how institutions provide us the required resources and strategies to increase our resilience. In the core of VT, the assets or resources can take five forms: physical, human, social, ecological or environmental and existential.

Consequently, and applied to the healthcare context, if our purpose is to diminish the healthcare professionals suffering, the focus should not be on trying to define and address separate instances of vulnerability, but on increasing resilience: fostering resilience in healthcare professionals as well as in patients and their families. The first step is recognition of our shared vulnerability. This recognition implies:

Patients, healthcare professionals and healthcare systems are all vulnerable.

Vulnerability can be generative and fruitful, since it has the capacity to promote connection with each other.

We need to develop resilience as a continuing, even though necessarily incomplete solution for our vulnerability.

Resilience is not a personal choice, and it is dependent on the resources and response that healthcare institutions provide.

In this regard, VT focuses on the inequality of resilience because it directs the attention to society and social institutions. Importantly, the resilience produced within social institutions and relationships over time reminds us that vulnerability is not only about negative consequences, but is also about generative and positive possibilities — it is intimately entwined with social structures and relationships because it is a matter of ontological interrelatedness. How can professionals and institutions build resilience? Focusing on healthcare, it is important to analyse what are some of the strategies that healthcare institutions and faculties can implement to try to improve resilience in professionals and also, patients and their families. It is crucial that it is recognised that resilience can be learnt; promoting resilient attitudes and practices is an indispensable responsibility that the institutions of healthcare must assume. We argue that through the development of CoP, the resilience of healthcare professionals can be enhanced.

Communities of practice: from vulnerability to resilience

We understand CoP as groups of people who share a practice, and for the purposes of this paper, we refer to the practice of healthcare. Further, the group cares about the same topics, share tacit knowledge and meets regularly to guide each other through their understanding of mutually recognised real-life problems.45 In addition to intentional facilitation to foster trust and safety, Pyrko et al 45 suggests mutual engagement of all members is also essential. This supports thinking together as a transpersonal process, wherein people focus on the same cue and require a certain indwelling.46

Lave and Wenger’s47 initial description of CoP emphasised how novices participate in practice, beginning at the periphery of professions, using culturally and historically rich examples. One narrative illustrated how the daughters or granddaughters of Yucatec midwives were socialised into the practice of midwifery, without intentional teaching or learning. Situated learning emphasises the social interactions that support learning within a community of those who practice similar professions or in similar fields. In today’s knowledge society, not only novices, but all professionals require ongoing learning, which can be facilitated in a CoP.

Recent authors describe intentional development of CoPs by healthcare professionals following identification of a shared clinical problem, relevant to their day-to-day working lives.48 Within the CoP space, there is a constant to and constant exchange between external or clinical working lives and internal, lived experience. It is also suggested that the patient is at the centre of healthcare CoPs, as urgent clinical problems support CoP initiation.49 Since CoPs are problem-driven and patient-centred, they are conducive to a democratic style of discussion in which contributions are valued according to their salience to the problem rather than by formal status or discipline.

In terms of actual presentation, some CoPs may be primarily virtual, through online asynchronous and at times synchronous communication. Virtual CoPs may develop to address the needs of time-pressured, geographically distributed clinicians.50 However, it is recognised that CoPs function best when there is opportunity for face-to-face communication and the development of relationships. As our premise is that CoPs support both vulnerability and resilience within relationships: it is valuable to consider how these elements may intersect beneficially.

McLoughlin et al 50 suggest that virtual CoPs (vCoP) reduce hierarchical barriers and support sharing information and learning from one another. However, the development of trust within the vCoP requires some face-to-face meetings to ensure relationships develop. The platform used must also ensure privacy and safety. Given an emphasis on maintaining credibility and conveying expertise in healthcare environments, healthcare providers may be reluctant to be vulnerable. Experts with knowledge are often considered to have power. Sharing thought processes, or brainstorming may effectively support vulnerability and enhance trust.51 When these parameters are in place, as well as facilitation that supports communication, it is more likely that participants will be sufficiently trusting to seek help, provide support and learn from others.

The movement of CoPs from instrumental sharing of information to a valued relational process whereby healthcare professionals from varying contexts guide one another, is important to the focus of this paper. CoPs emphasise learning to support meaning and professional identity for day-to-day practice. In this regard, Pyrko et al 45 suggests that knowledge as information is silent. Through mutual engagement and reciprocal trust by members, CoPs have the potential to unearth, articulate and benefit from tacit, previously unarticulated knowledge held by individuals or teams about the shared problem.52 That is, the Polyani46 considered tacit knowledge as the knowledge gained through experience and practice, related closely to skills and experience, which is often not articulated. Tacit knowledge may be articulated, primarily through metaphors, comparisons and narratives. It is a process that requires thoughtful facilitation and a reduction of hierarchies. With facilitation that sees the potential in everyone and supports openness to everyone’s ideas, trust and psychological safety can be cultivated within the CoP.48 49 This may allow the vulnerability to admit uncertainty and a need for help. In turn, the group’s capacity to generate innovative solutions contributes to greater resilience. As well, the CoP has the potential to contribute to health providers’ social and professional identity formation.

Communities of practice, vulnerability and resilience

The VT emphasises institutional responsibility in relation to universal vulnerability. The emphasis shifts to institutional arrangements, and the need for a regulatory framework. In addition, it is pointed out that institutions themselves, as human creations, are vulnerable and therefore must be monitored and reformed when not functioning justly. On the other hand, Wenger53 argues that organisations must cultivate communities of practice to support development of expertise and innovation. That is, CoPs may foster emergent knowledge,54 through combining tacit and explicit knowledge. This process of ‘thinking together’45 can help professionals to be more confident, to increase the trust in the team and to support each other. CoPs also promote practical wisdom and how one’s clinical experiences may extend one’s knowledge in healthcare. By reflecting on and reconsidering assumptions, a state of ‘mental unrest and disturbance’ may trigger professional development and accepting new ideas.55 Ultimately, all these factors that arise from the CoP increase resilience to manage difficulties that can appear, especially in healthcare context.

Institutional benefits from CoPs include both personal and organisational outcomes of developing new knowledge and expertise, gaining competencies, reducing geographical and organisational barriers and diminishing professional isolation.54 These benefits may have wider implications for institutional environments. Emerging informal knowledge may be used for institutional strategic development. Since VT positions vulnerability as an outcome of social institutions and relationships, CoPs may have a reciprocal role between individuals and institutions as an intermediate structure between the two. Less is written about the factors that influence the evolution of a potential group to a mature group to facilitate resilience. We suggest that the capacity to support vulnerability and contribute to innovation may be important.

All of the above characteristics of CoPs are congruent with the conceptualisation of vulnerability and resilience in VT. Whereas CoP is a structured space, conditioned by expectations of democratic, non-hierarchical communication and mutual respect, vulnerability can come to expression in such a space. Applied to concrete situations from practice and guided by a commitment to seeking ethically and clinically sound solutions, CoPs can be seen as a good fit with VT. The emphasis on tacit knowledge and internal states of participants as part of professional identity, in addition to propositional knowledge, further reinforces the fit of CoPs with VT since vulnerability is an aspect of being, not just a contingent state.

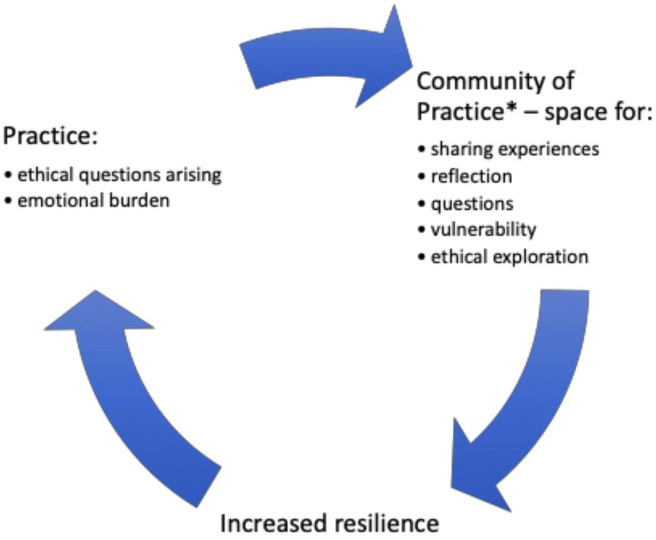

Figure 1 shows how we model the relationship between the cyclical structure of CoPs, vulnerability and resilience. According to VT, healthcare professionals are naturally vulnerable as human beings. Vulnerability can be connective and generative but for it to become a source of positive development there needs to be a social environment that is conducive to trusting communication. Such communication can happen spontaneously among colleagues, but CoPs constitute an intentional and purposeful space to promote sharing of experiences arising in clinical practice. The diagram shows there is an iterative flow from practice itself into the reflective space of the CoP, whose members have an opportunity to express vulnerability through addressing ethical problems and exploring alternative points of perspective and courses of action. Where there is a supportive environment, governed by a common interest in providing good care prior to hierarchical or disciplinary differences, discussion may reduce clinicians’ sense of isolated responsibility, promote resilience and open dialogue. Greater resilience may in turn have a positive effect on how clinicians cope with the stress of practice. It will not, of course, remove future challenges and ethical problems. Hence, the cyclical nature of using CoPs to take up questions from practice and to foster trusting relationships in which vulnerability can be expressed and allowed to become a catalyst for creative clinical reasoning.

Figure 1.

Community of practice (CoP) and vulnerability. *CoP, conditions of: relationships, dialogue, trust, time (continuity).

Conclusion

Health professionals can witness pain, death, illness, loss, anger, anxiety and pain in their practice. These situations deeply affect the most existential aspects of human life: birth and death, love and loss, suffering and recognition of our limitations and put professionals in a unique position of vulnerability that requires more recognition. The CoPs constitute an intentional space to promote the exchange of experiences arising in clinical practice. Because of that, the CoP within healthcare teams can be of great value in addressing the inherent vulnerability that arises from the practice of healthcare. These spaces of openness to share different experiences of vulnerability and learn together from them are necessary in order to increase resilience collectively. We believe that the model developed in the diagram shown can be of significant value in the training and functioning of healthcare teams.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Antonio Casado da Rocha for his inspiring comments that led to this research, and Professor Martha A. Fineman for her stimulating comments and review to the paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors have contributed to design the main ideas on this research through discussions and meetings. JD, JdG and GM conducted the research and wrote the main body of the manuscript. GD, KS and WA have contributed to review the report, and to introduce changes for clarity. All the authors have approved the final manuscript. All the authors have contributed to the review of the paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

There are no data in this work

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Fineman MA. The vulnerable subject: anchoring equality in the human condition. Yale Journal of Law & Feminism 2008;20(1). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Delgado J. The relevance of the ethics of vulnerability in bioethics. Les ateliers de l'éthique The Ethics Forum 2017;12(2-3):253–79. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fineman MA. The vulnerable subject and the responsive state. Emory Law J 2010;60(2). [Google Scholar]

- 4. Austin W, Goble E, Leier B, et al. Compassion fatigue: the experience of nurses. Ethics and Social Welfare 2009;3(2):195–214. 10.1080/17496530902951988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Austin W, Brintnell ES, Goble E, et al. Lying down in the ever-falling snow: Canadian health professionals’ experience of compassion fatigue. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ulrich C, Grady C. Moral distress in the health professions. University Press, Springer International, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carel H. A reply to 'Towards an understanding of nursing as a response to human vulnerability' by Derek Sellman: vulnerability and illness. Nurs Philos 2009;10(3):214–9. 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2009.00401.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fineman MA. “Elderly” as vulnerable: Rethinking the nature of individual and societal responsibility. The Elder Law J 2012;20(1):71–112. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Austin W. Engagement in contemporary practice: a relational ethics perspective. Texto contexto - enferm 2006;15(spe):135–41. 10.1590/S0104-07072006000500015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robertson IT, Cooper CL, Sarkar M, et al. Resilience training in the workplace from 2003 to 2014: a systematic review. J Occup Organ Psychol 2015;88(3):533–62. 10.1111/joop.12120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nissim R, Malfitano C, Coleman M, et al. A qualitative study of a compassion, presence, and resilience training for oncology interprofessional teams. J Holist Nurs 2019;37(1):30–44. 10.1177/0898010118765016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoffmaster CB. What does vulnerability mean? Hastings Center Report 2006;36(2):38–45. 10.1353/hcr.2006.0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goodin R. Protecting the vulnerable. A reanalysis of our social responsibilities. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gilligan C. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Caring NN. A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. California: University of California Press, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tronto JC. Moral boundaries: a political argument for an ethic of care. New York: Routledge, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baier A. Moral Prejudices: essays on ethics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fineman MA. The Neutered mother, the sexual family and other twentieth century Tragedies. New York: Routledge, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kittay E. Love’s labor: Essays on women, equality, and dependency. New York: Routledge, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Held V. The ethics of care: personal, political, and global. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ten Have H. Vulnerability: challenging bioethics. New York: Routledge, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luna F. Bioethics and vulnerability: a Latin American view. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luna F. Elucidating the concept of vulnerability: layers not labels. Int J Fem Approaches Bioeth 2009;2(1):121–39. 10.3138/ijfab.2.1.121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Luna F, Vanderpoel S. Not the usual suspects: addressing layers of vulnerability. Bioethics 2013;27(6):325–32. 10.1111/bioe.12035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luna F. Rubens, corsets and Taxonomies: a response to Meek Lange, Rogers and Dodds. Bioethics 2015;29(6):448–50. 10.1111/bioe.12109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mackenzie C, Rogers W, Dodds S. Vulnerability: new essays in ethics and feminist philosophy (studies in feminist philosophy). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levinas E. Totalité et Infini: essai sur l'extériorité. 1961.Translation Levinas, E. Totalidad e infinito. Salamanca: Sígueme, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levinas E. Humanisme del'autre homme. 1972. Translation Levinas, E. Humanismo del otro hombre. 1998. Madrid: Caparrós, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 29. MacIntyre A, Animals DR. Why human beings need the virtues. Chicago: Open Court, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nusbaum M. Frontiers of justice: disability, Nationality, species membership. Cambridge: Harvard, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Butler J. Frames of war. London, New York: Verso, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Butler J, life P. The power of the mourning and violence. London, New York: Verso, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ricoeur P. Lo justo 2. Estudios, lecturas Y ejercicios de ética aplicada. Madrid: Trotta, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turner B. Vulnerability and human rights. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pelluchon C. L’autonomie brisée. Bioéthique et philosophie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fineman MA. Vulnerability and inevitable inequality. Oslo Law Review 2017;1(03):133–49. 10.18261/issn.2387-3299-2017-03-02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guerra MJ. Vivir con los otros y/o vivir para los otros. Autonomía, vínculos y ética feminista. Dilemata 2009;1:71–83. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haramati A, Weissinger PA. Resilience, empathy, and wellbeing in the health professions: an educational imperative. Glob Adv Health Med 2015;4(5):5–6. 10.7453/gahmj.2015.092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schwarz S. Resilience in psychology: a critical analysis of the concept. Theory Psychol 2018;28(4):528–41. 10.1177/0959354318783584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. American Psychological Association . The road to resilience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2014. http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 41. Southwick SM, Bonanno GA, Masten AS, et al. Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2014;5(1):25338. 10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pietrzak RH, Southwick SM. Psychological resilience in OEF–OIF veterans: application of a novel classification approach and examination of demographic and psychosocial correlates. J Affect Disord 2011;133(3):560–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fineman MA. Vulnerability, Resilience, and LGBT Youth. Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review, Forthcoming; Emory Legal Studies Research Paper, 2014: 14–292. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Resilience Research Centre . What is resilience? Available: http://resilienceresearch.org/resilience/ [Accessed Dec 2019].

- 45. Pyrko I, Dörfler V, Eden C. Thinking together: what makes communities of practice work? Human Relations 2017;70(4):389–409. 10.1177/0018726716661040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Polyani M. The tacit dimension. London, England: Doubleday and company, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge UK: Cambridge Universities Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 48. de Carvalho-Filho MA, Tio RA, Steinert Y. Twelve tips for implementing a community of practice for faculty development. Med Teach 2019;14:1–7. 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1552782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Young J, Jaye C, Egan T, et al. Communities of clinical practice in action: doing whatever it takes. Health 2018;22(2):109–27. 10.1177/1363459316688515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, et al. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care 2018;32(2):136–42. 10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Molloy E, Bearman M. Embracing the tension between vulnerability and credibility: ‘intellectual candour’ in health professions education. Med Educ 2019;53(1):32–41. 10.1111/medu.13649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kothari AR, Bickford JJ, Edwards N, et al. Uncovering tacit knowledge: a pilot study to broaden the concept of knowledge in knowledge translation. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11(1):198. 10.1186/1472-6963-11-198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization 2000;7(2):225–46. 10.1177/135050840072002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nonaka I. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science 1994;5(1):14–37. 10.1287/orsc.5.1.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Eriksen Kristin Ådnøy, Dahl H, Karlsson B, et al. Strengthening practical wisdom: mental health workers' learning and development. Nurs Ethics 2014;21(6):707–19. 10.1177/0969733013518446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no data in this work