PURPOSE

Metastatic uveal melanoma has poor overall survival (OS) and no approved systemic therapy options. Studies of single-agent immunotherapy regimens have shown minimal benefit. There is the potential for improved responses with the use of combination immunotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a phase II study of nivolumab with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Any number of prior treatments was permitted. Patients received nivolumab 1 mg/kg and ipilimumab 3 mg/kg for four cycles, followed by nivolumab maintenance therapy for up to 2 years. The primary outcome of the study was overall response rate (ORR) as determined by RECIST 1.1 criteria. Progression-free survival (PFS), OS, and adverse events were also assessed.

RESULTS

Thirty-five patients were enrolled, and 33 patients were evaluable for efficacy. The ORR was 18%, including one confirmed complete response and five confirmed partial responses. The median PFS was 5.5 months (95% CI, 3.4 to 9.5 months), and the median OS was 19.1 months (95% CI, 9.6 months to NR). Forty percent of patients experienced a grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse event.

CONCLUSION

The combination regimen of nivolumab plus ipilimumab demonstrates activity in metastatic uveal melanoma, with deep and sustained confirmed responses.

INTRODUCTION

Uveal melanoma is the most common primary intraocular malignant tumor in adults. It is the second most common type of primary malignant melanoma but represents only 5% to 6% of all melanoma diagnoses.1 The incidence of uveal melanoma globally is approximately 4,800 persons per year, with nearly 2,000 cases diagnosed in North America annually.2 Although there are effective local therapies for uveal melanoma, approximately 40% to 50% of patients will ultimately develop distant disease. The liver is involved in up to 95% of individuals who develop metastatic disease. Once metastatic disease is identified, the median survival of patients is 6 to 12 months despite therapy.3 There is no standard therapy for metastatic uveal melanoma, and a significant unmet need for these patients remains.4

CONTEXT

Key Objective

This study addressed the question of whether the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab has clinically significant activity in treating metastatic uveal melanoma, a condition for which there are no US Food and Drug Administration–approved therapies.

Knowledge Generated

This single-arm phase II study of nivolumab and ipilimumab in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 18%, a median progression-free survival of 5.5 months, and a median overall survival of 19.1 months.

Relevance

These results indicate that nivolumab and ipilimumab have activity in treating metastatic uveal melanoma and are consistent with results reported in the GEM1402 study, a European trial using the combination. The ORR for nivolumab and ipilimumab is higher than the response rates reported for single-agent immunotherapy in this population.

Immunotherapy using checkpoint inhibitors has revolutionized the treatment and outcomes of cutaneous melanoma; however, the usefulness of immunotherapy in melanomas of rare subtypes, including uveal melanoma, requires additional investigation. Studies of single-agent checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated low response rates. A phase II trial of single-agent ipilimumab showed a 0% overall response rate (ORR) and a median overall survival (OS) of 6.8 months,5 and another trial of single-agent tremelimumab again demonstrated no responses, with an OS of 12.8 months.6 Similarly, a report of patients treated with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) agents such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab showed a 3.6% ORR and a median OS of 7.6 months.7

The combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab in cutaneous melanoma is marked by early tumor shrinkage, with an improvement in objective response rate when compared with single-agent therapy.8,9 However, the combination yields increased rates of immune-related toxicities. Nevertheless, we hypothesized that dual checkpoint inhibition would generate pronounced antitumor responses in metastatic uveal melanoma. Here, we report the results of a phase II study of nivolumab plus ipilimumab for metastatic uveal melanoma.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a single-institution, open-label, single-arm phase II study of nivolumab and ipilimumab in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. The primary end point of the study was ORR, with secondary end points of median progression-free survival (PFS), median OS, and 1-year OS. During the induction phase of treatment, patients were administered nivolumab 1 mg/kg intravenously (IV) plus ipilimumab 3 mg/kg IV every 3 weeks, for a total of four doses. During the subsequent maintenance phase, treatment was continued with nivolumab. Nivolumab was dosed initially at 3 mg/kg IV every 2 weeks, but during the time period of the study, the dosing was changed to 480 mg IV every 4 weeks because of a change in US Food and Drug Administration labeling. Treatment was continued for up to 104 weeks or until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, death, or withdrawal of consent. The Protocol (online only) was approved by the institutional review board at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and was conducted under the principles of the International Council of Harmonization and Good Clinical Practice. Drug and funding for this investigator-sponsored research study were provided by Bristol Myers Squibb (New York, NY) to support the study. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Patient Selection

Patients included in the study were ≥ 18 years old with a history of uveal melanoma and documented metastatic disease, with at least one measurable lesion on imaging measuring ≥ 1 cm or ≥ 1.5 cm in short axis for nodal disease on spiral computed tomography (CT) or equivalent. Any number of prior treatments was permitted. Patients were required to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1 and acceptable end-organ function as determined by baseline laboratory data. Other key inclusion criteria were the ability to give informed consent; the absence of active or chronic infection with HIV, Hepatitis B, or Hepatitis C; the passage of more than 21 days from surgery, radiation therapy, or prior chemotherapy; and the passage of more than 42 days from prior immune therapy including vaccines. Patients were excluded from the study because of the presence of bone-only metastatic disease; a second primary malignancy from which the patient had been disease free for less than 2 years (excluding adequately treated basal or squamous cell skin cancer, superficial bladder cancer, or carcinoma in situ of the cervix, breast, or prostate); a history of autoimmune disease; or concomitant therapy with nonstudy immunotherapy, cytotoxic chemotherapy, immunosuppressive agents, or chronic use of systemic corticosteroids greater than physiologic replacement doses.

Patient Monitoring and Response Assessments

Adverse events were assessed using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Patients were monitored via adverse event assessments, common laboratory tests, and liver function tests with each treatment during induction and every 4 weeks thereafter until removed from study. All patients enrolled were evaluable for toxicity from enrollment to 100 days after the last dose of study drug. Response to treatment was monitored via imaging at week 12 and then every 12 weeks until progression or treatment discontinuation. Assessments for response included evaluation of the chest, abdomen, pelvis, and all known sites of disease, using the same imaging method as at baseline (CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging). Tumor assessments for ongoing study treatment decisions were completed by the investigator using RECIST 1.1 criteria.10 Clinical progression warranting alternative therapy was considered only in patients whose overall tumor burden seemed to be substantially increased and/or in patients whose performance status decreased.

Statistical Analysis

A single-stage trial design was used in which the primary outcome was ORR, defined as the percentage of patients achieving either a confirmed partial response (PR) or complete response (CR). The target ORR was 20% with a null hypothesis of a 5% response rate. The target enrollment was 27 patients, giving 80% power with a type I error of 0.05. The trial originally used a Simon’s two-stage design to target a response rate of 15% with an interim analysis planned after the first 27 patients; however, after ongoing review, it was felt that a 15% response rate would not outweigh the toxicity rate, and the target response rate was increased to 20% in a single-stage design. A total of 23 evaluable patients had been enrolled at the time of this change, of whom three achieved a response. Overall, 35 patients were enrolled in the trial to account for anticipated patients who would be unevaluable for response.

The ORR was presented with the corresponding 95% exact CI, and a one-sample test of proportions was used to test the null hypothesis. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to assess the distribution of time-to-event variables including OS and PFS. A landmark analysis was performed to compare PFS by incidence of toxicity while addressing the issue of immortal survival time among patients experiencing toxicities. Only patients who were alive and progression free (and had not been censored) at 4 months after the study enrollment were included in this analysis, and PFS was indexed at patients’ 4-month landmark date. Data analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) and GraphPad Prism 7 Software (La Jolla, CA). All authors had full access to the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

Patients

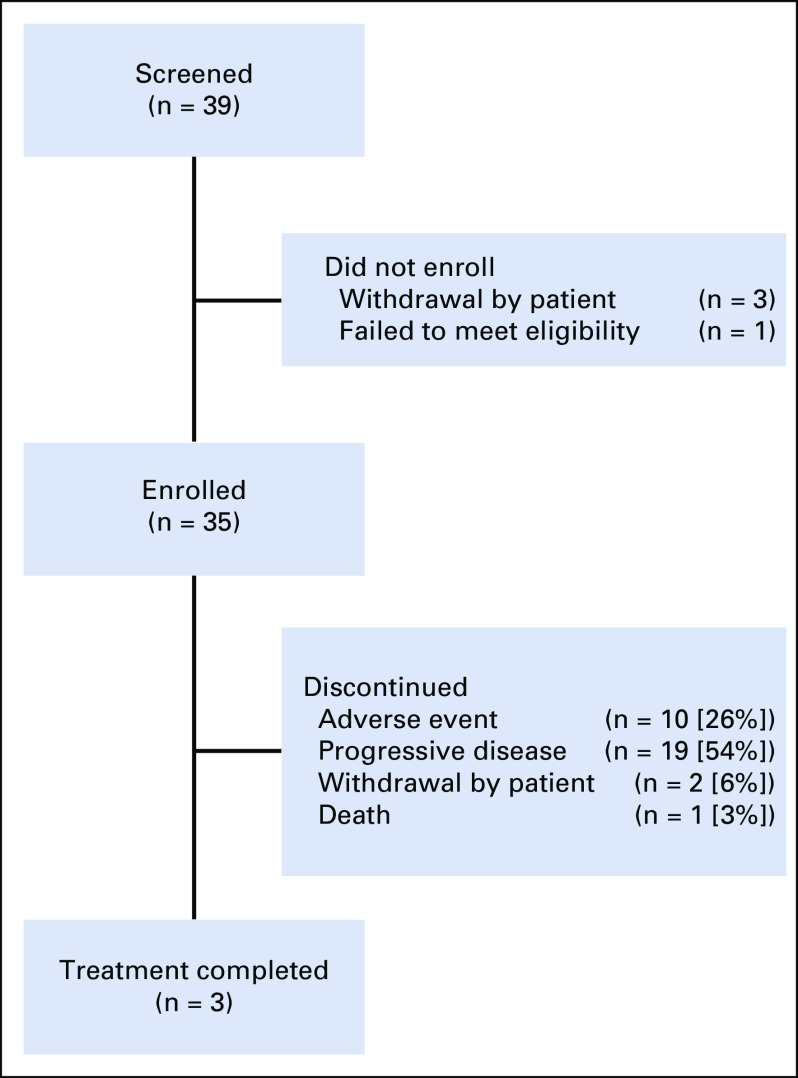

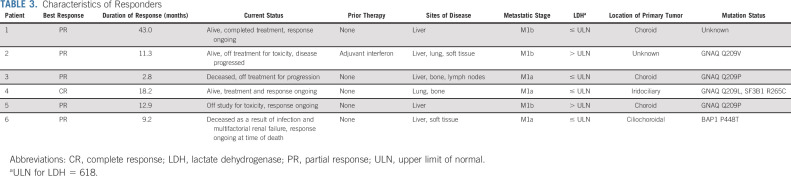

From July 7, 2015 through March 7, 2018, 39 patients were screened for the study. Thirty-five patients were enrolled and received at least one treatment and were evaluable for toxicity (Fig 1). The median follow-up period was 13.0 months (range, 1.3- 43.5 months). Two patients were unevaluable for response because of a lack of follow-up imaging (one patient died as a result of sepsis from an unrelated cause, and one patient developed postinfectious complications after cholecystitis and was removed with no additional imaging from the study). Of the 33 patients evaluable for response, four did not have tumor measurements but had clear clinical evidence of disease progression. Three responses occurred before the change in study design from a two-stage to a single-stage design, and an additional three responses occurred afterward. The median age at diagnosis was 62 years, and 34% of patients were male. Tumor genetic information was available for 22 (63%) of the 35 patients. Of those with available tumor mutation information, 73% had a GNAQ mutation, whereas 23% had a GNA11 mutation. One patient (3%) had wild type with a BAP1 mutation. Overall, only seven patients had testing with an extended panel to analyze for BAP1 and SF3B1 mutations; of these, three had no additional mutations besides GNAQ or GNA11, two had a BAP1 mutation, and two had an SF3B1 mutation. Testing for EIF1AX, CYSLTR, and PLCB4 was not available. Forty-nine percent of patients had both hepatic and extrahepatic metastases at the time of study enrollment, with lung, bone, and soft tissue the most common extrahepatic sites of metastasis. The majority of patients had stage IV M1a or M1b disease (49% and 40%, respectively), and 43% of patients had a baseline elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Fifteen patients (43%) had received one or more prior lines of therapy, most commonly targeted therapy. Two of these 15 patients (13%) had received prior immunotherapy with pembrolizumab. A summary of patient characteristics is presented in Table 1. Completion of all four induction cycles occurred in 19 patients (54%), and three patients (9%) completed 2 years of maintenance nivolumab. The median duration of treatment was 16 weeks, with a range of 4 to 106 weeks.

FIG 1.

Patient disposition. Thirty-nine patients were screened for the study, and four screen failures occurred because of withdrawal of consent or failure to meet eligibility criteria. Thirty-five patients were enrolled and treated in the study; 33 patients were evaluable for response, and three patients completed treatment.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics

Efficacy

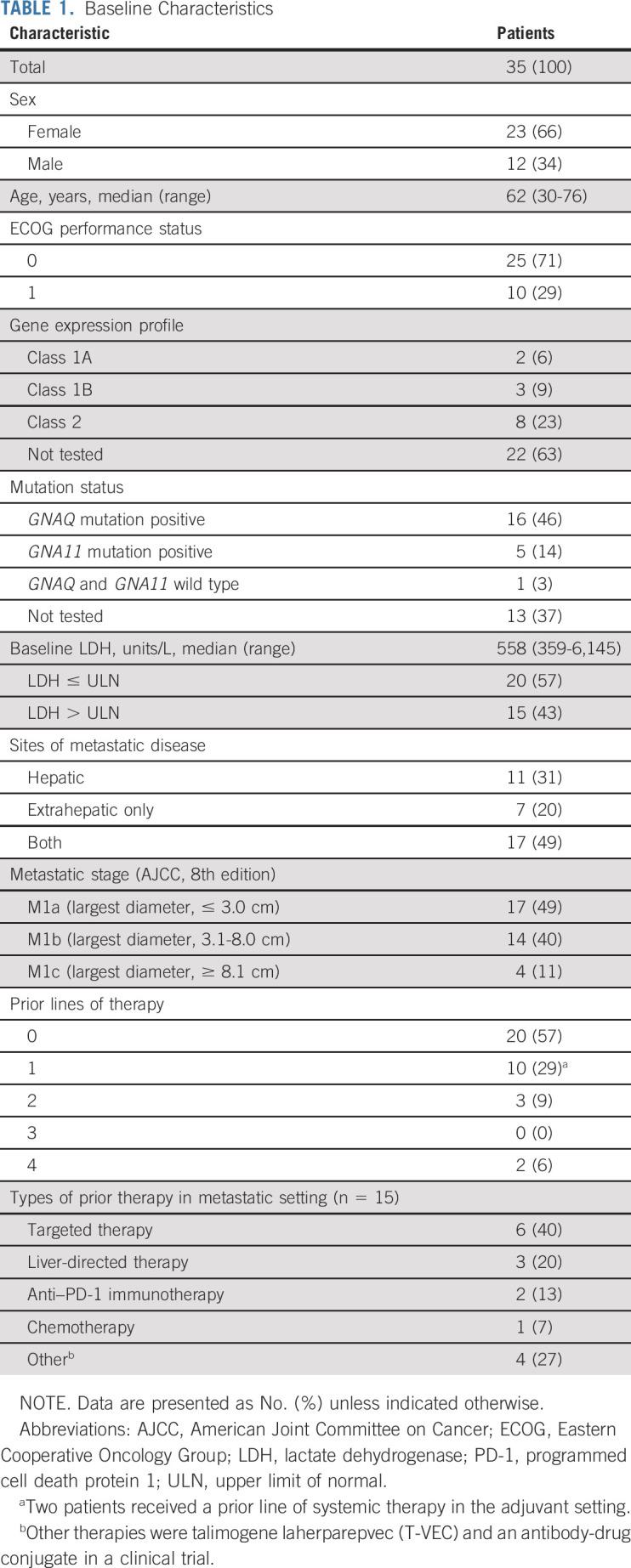

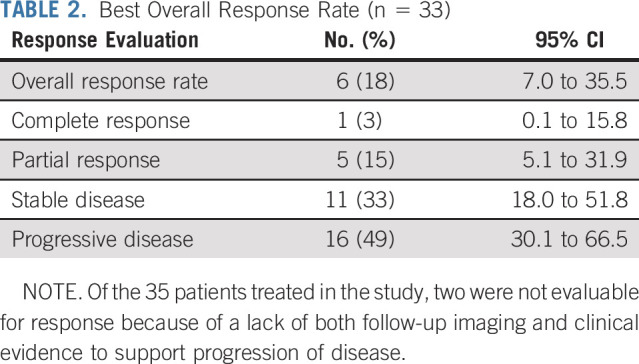

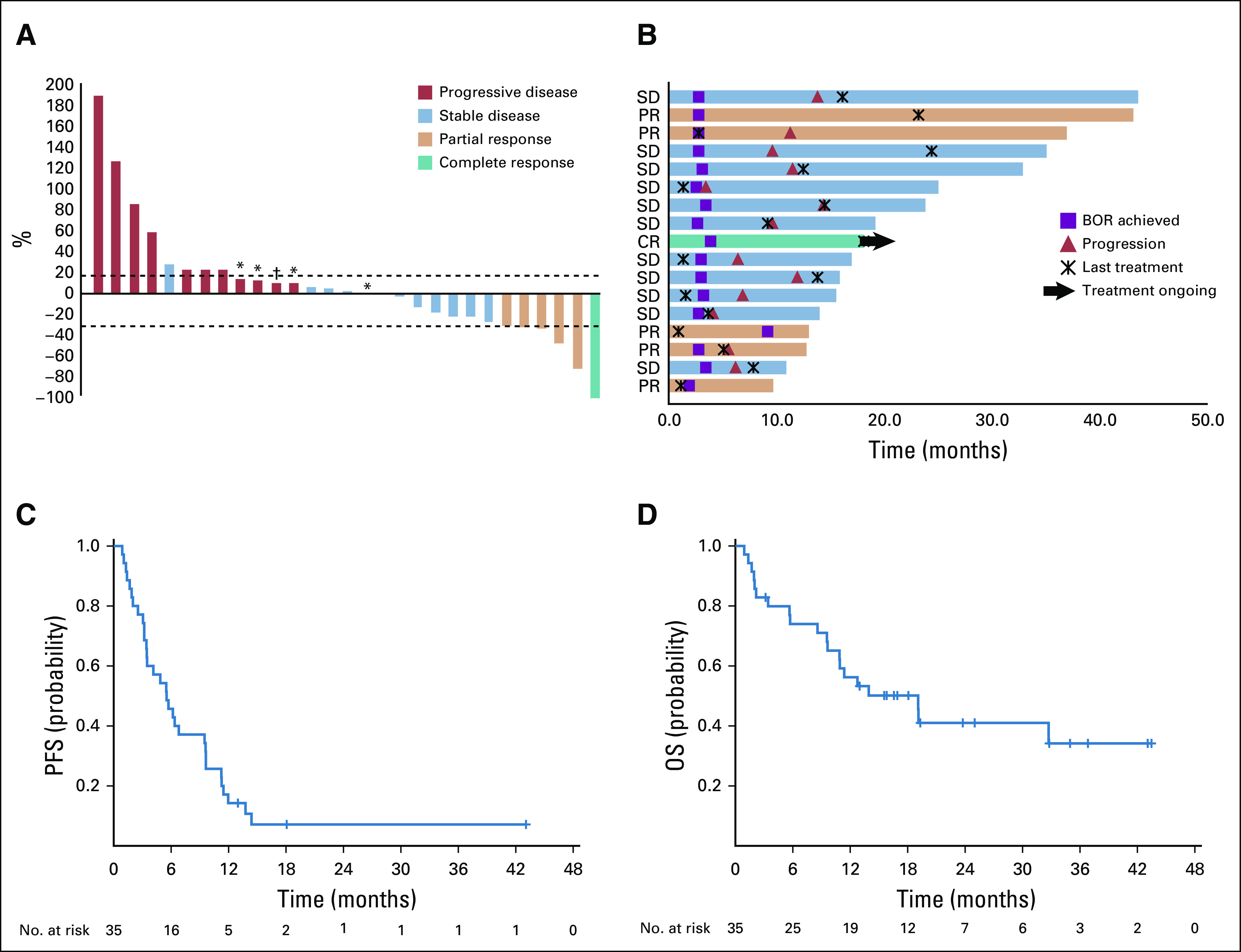

The median duration of follow-up was 13.0 months. The ORR of treated patients was 18% (95% CI, 7.0% to 35.5%; Table 2). On the basis of this observed ORR, the null hypothesis of a 5% response rate was rejected (P = .0003). Of six patients who achieved a response, one had a CR and five had a PR per RECIST 1.1; all responses were confirmed. Eleven patients, or 33%, had a best response of stable disease, with six of these patients maintaining this response for at least 6 months. Overall, 41% of evaluable patients experienced a reduction from baseline in target lesion size (Fig 2A). The median percentage change in tumor burden was 3.0%. In patients with a CR or PR or stable disease, the median percentage tumor change was −21.0%.

TABLE 2.

Best Overall Response Rate (n = 33)

FIG 2.

Efficacy of nivolumab and ipilimumab. (A) The best percentage change from baseline in target lesions by RECIST 1.1 (n = 29). Of the 33 patients evaluable for overall responses, four did not have tumor measurements. These patients had progressive disease. (*) Less than 20% increase in target lesions but progression of nontarget lesions. (†) Less than 20% increase in target lesions but development of new lesion. (B) Treatment exposure and response duration in patients with a confirmed complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) or stable disease (SD) via RECIST 1.1 (n = 17). (C) Kaplan-Meier estimate of progression-free survival (PFS) by RECIST 1.1. For the 35 patients in the study, the median PFS was 5.5 months (95% CI, 3.4 to 9.5 months). (D) Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival (OS). For the 35 patients included in the study, the median OS was 19.1 months (95% CI, 9.6 months to NR), and the 1-year OS was 56% (95% CI, 38% to 71%). BOR, best overall response.

Twenty-seven evaluable patients had liver metastases, of whom five (19%) had a PR and three (11%) had stable disease for 6 months or longer. The remaining six patients had extrahepatic sites of metastases only. One of these patients (17%) achieved a CR, and three (50%) achieved stable disease for 6 months or more.

Two patients received prior treatment with single-agent anti–PD-1 therapy. Of these patients, one achieved stable disease and one had progressive disease on nivolumab and ipilimumab. The ORR in the 31 evaluable patients who were checkpoint naïve was 19%. The patient who achieved stable disease in this study had received 34 cycles of pembrolizumab after being rendered disease free from surgical excision of a subcutaneous metastasis. She then developed a new subcutaneous metastasis after 31 cycles of pembrolizumab, at which point talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) was added. There was continued disease progression, at which time her therapy was changed to enrollment in this study. The patient who had progressive disease on nivolumab and ipilimumab had received pembrolizumab with pegylated interleukin-10 in a clinical trial 18 months before enrollment in this study. She had achieved stable disease with this regimen before eventually developing disease progression after seven cycles. In the interval before starting therapy in this study, she received treatment in clinical trials with targeted therapy, an antibody-drug conjugate, and another targeted therapy.

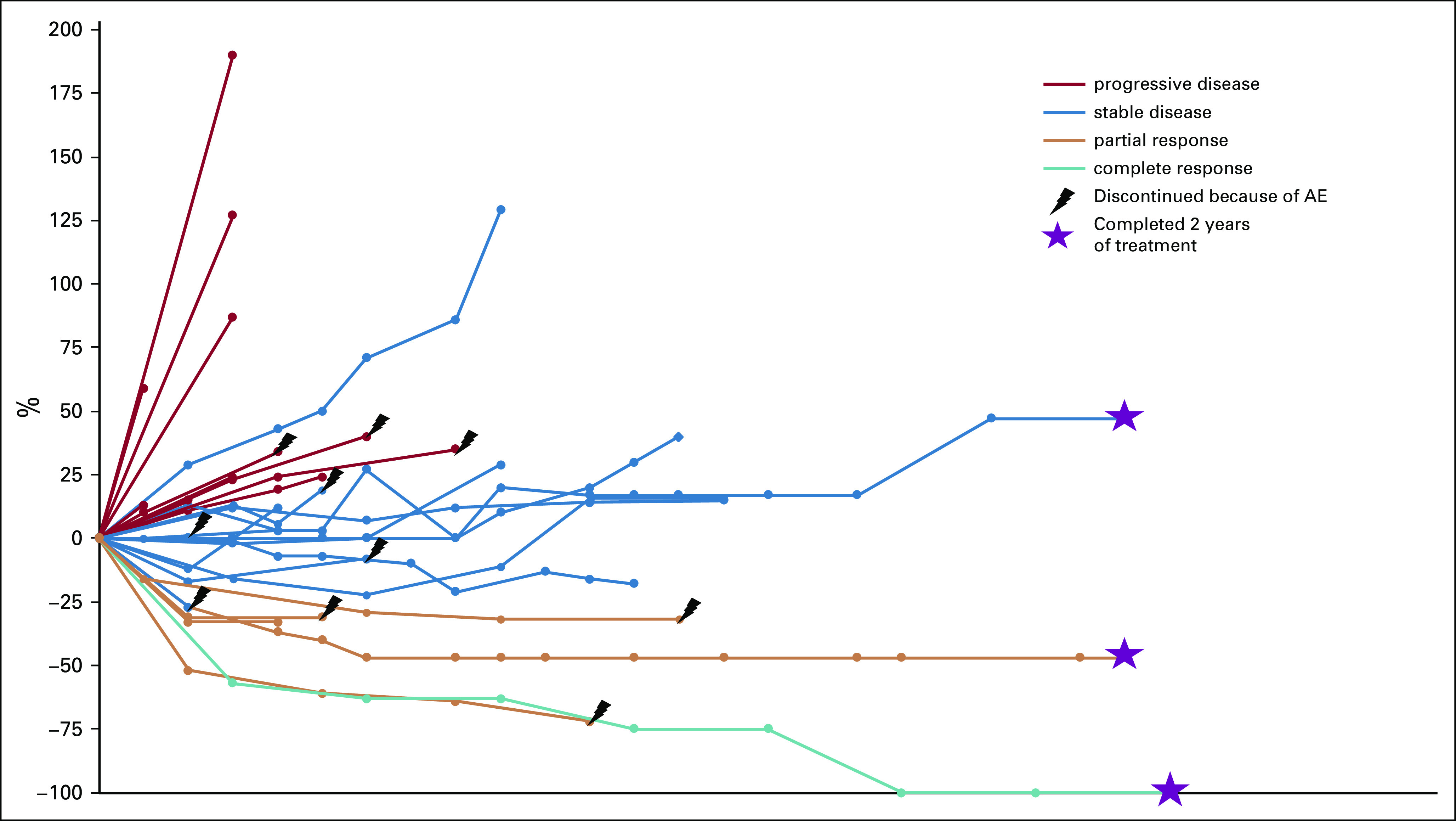

The median time to response was 2.7 months (range, 2.7-9.2 months; Fig 2B). The median duration of response in responders was 12.1 months (range, 2.8- 43.0 months), with a median treatment duration of 3.9 months (range, 1.2-23.2 months). At the time of data cutoff, three patients had an ongoing response. One responder was deceased as a result of another cause with an ongoing response at the time of death. One patient continued to receive study treatment. There were no cases of pseudoprogression (Appendix Fig A1, online only).

The characteristics of responders are described in Table 3. The median PFS was 5.5 months (95% CI, 3.4 to 9.5 months; Fig 2C). The median OS was 19.1 months (95% CI, 9.6 months to not reached [NR]), and the 1-year OS was 56% (95% CI, 38% to 71%; Fig 2D).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of Responders

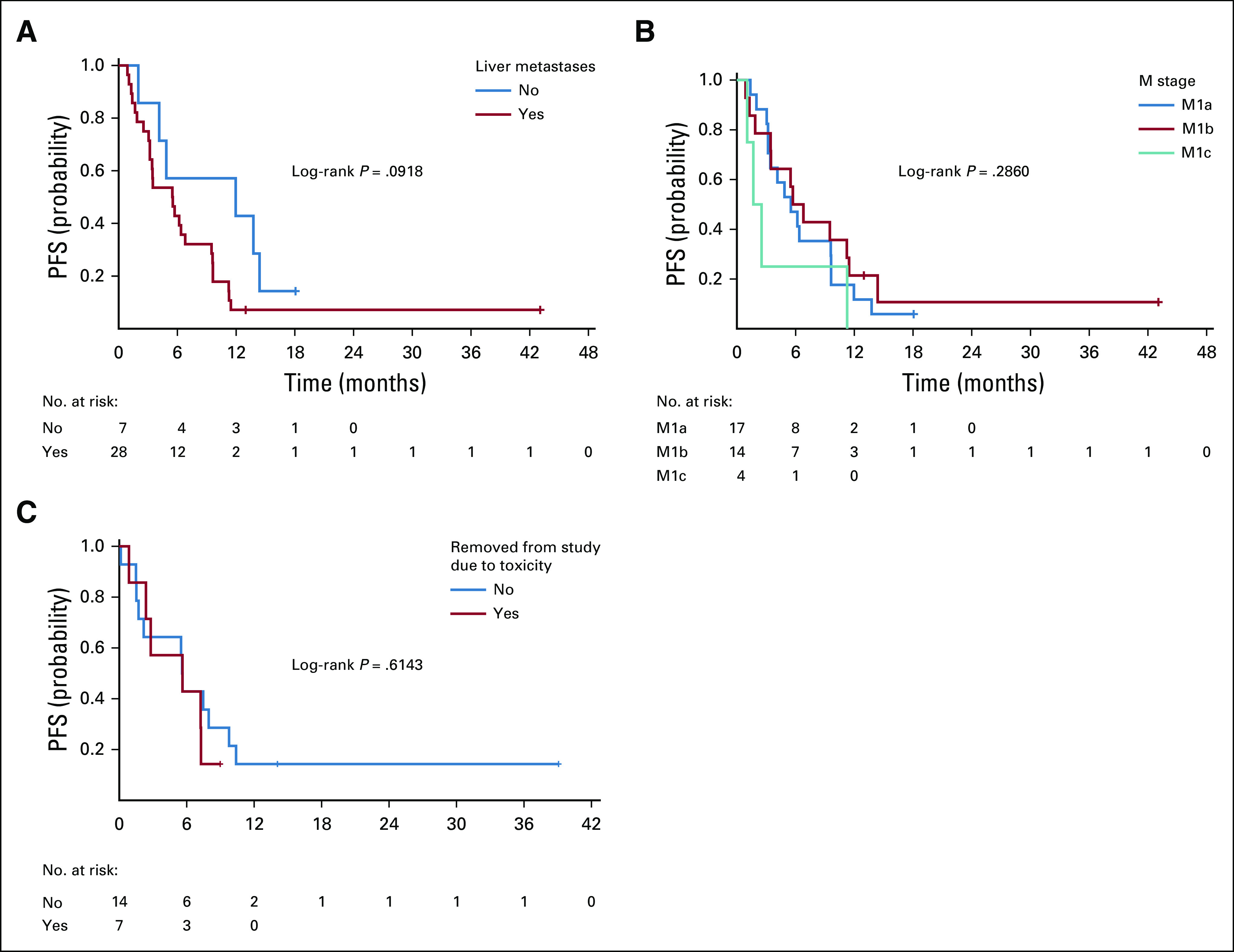

The median PFS was numerically longer in patients with extrahepatic sites of metastases only compared with patients with liver metastases; however, this difference was not statistically significant (Fig 3A). The median PFS was also not significantly different for patients with different American Joint Committee on Cancer M categories (Fig 3B). Similarly, the median OS was not significantly different for either comparison (data not shown).

FIG 3.

Progression-free survival (PFS) in subgroups. (A) PFS for patients with extrahepatic-only sites of metastases versus liver metastases was 12.0 months versus 5.5 months (P = .0918). (B) PFS for patients with different American Joint Committee on Cancer M categories of disease was not significantly different (M1a, 5.5 months; M1b, 6.3 months; M1c, 2.1 months; P = .2860). (C) PFS in patients removed from study for toxicities versus not removed from study was not significantly different (P = .6143). (*) Post 4-month landmark date.

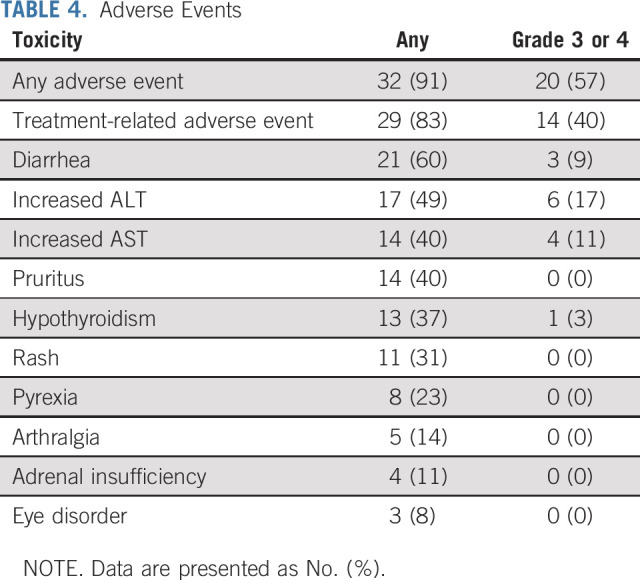

Adverse Events

Thirty-two patients (91%) experienced an adverse event, and 29 patients (83%) experienced a treatment-related adverse event (Table 4). Grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 14 patients (40%). The most common adverse events of any grade were diarrhea, abnormal liver enzymes, pruritis, and hypothyroidism. Ten patients (29%) were removed from the study because of adverse events. No treatment-related deaths occurred.

TABLE 4.

Adverse Events

Seven patients required systemic steroids for the management of immune-related adverse events, with a median steroid treatment duration of 6 weeks. Four of these patients were able to receive subsequent immunotherapy off protocol after management of toxicities. The PFS of patients removed from the study for toxicity was no different from that of patients not removed, based on a conventional landmark analysis indexed at 4 months after study enrollment (Fig 3C).

DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated that nivolumab and ipilimumab show activity in metastatic uveal melanoma, with an 18% ORR. In addition, the 18% of patients with stable disease for at least 6 months could be argued to have benefit from the combination, yielding a clinical benefit rate of 36%. Compared with the sentinel publication on the use of nivolumab and ipilimumab in cutaneous melanoma, there were no new safety signals detected in the uveal melanoma population.8

The ORR of 18% is encouraging compared with those of prior therapies including single-agent checkpoint inhibitors, which have shown a 0% to 3.6% response rate,5-7 and targeted therapies, such as selumetinib in combination with dacarbazine, which achieved a 3% response rate.11

In addition, nivolumab and ipilimumab yielded an improvement in PFS and OS compared with single-agent immunotherapy. The OS with nivolumab and ipilimumab of 19.1 months is notably longer than the 6.8 to 9.6 months reported with single-agent checkpoint inhibition. A recent meta-analysis of patients in clinical trials with various agents for metastatic uveal melanoma, not including the current study, showed a median PFS of 3.3 months and a median OS of 10.2 months, with a 1-year OS rate of 43%.12 These data were intended to serve as a new benchmark in uveal melanoma, and the results of the current study demonstrate improvement.

Results from this study of nivolumab and ipilimumab are consistent with those reported from the Spanish GEM-1402 study of these agents used in the first-line setting in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Nevertheless, this study, as well as that of GEM-1402, is limited by the small sample size. The small number of patients reduces our ability to correlate clinical features with response. However, it is notable that none of the six responders in our study had received prior therapy in the metastatic setting.

The small number of patients in the study also makes assessment of clinical factors predictive of response difficult; however, our analyses indicate a numeric improvement in PFS and OS in patients who have extrahepatic disease only. The patient with a CR had extrahepatic disease only. This patient had an iridociliochoroidal uveal melanoma that progressed in the eye less than 3 months after brachytherapy, warranting enucleation of a 21-mm tumor spanning the entire globe. One and one half years later, she required urgent laminectomy for metastasis to the thoracic spine and was left with metastatic disease to the lung. Her primary and metastatic melanoma tissue harbored a GNA11 and SF3B1 mutation, consistent with uveal melanoma. The current literature supports the notion that metastatic uveal melanomas harboring an SF3B1 mutation have a good prognosis compared with those absent the mutation but not when compared with those with EIF1AX mutations. This may be related to the development of a primarily extrahepatic metastasis, as in this patient’s case. Also of note, three responders had significant immune-related adverse events that led to early discontinuation of study drug, but they maintained a response to treatment. One of these responders subsequently developed recurrent infections and multifactorial renal failure months after stopping therapy and ultimately decided to pursue comfort measures before her death.

On-treatment biopsy specimens are available for some patients who participated in this study, and correlative analyses will aid in additional study of responders and nonresponders. These analyses are underway and will be reported subsequently. At initial review, responders demonstrate an upregulated pretreatment interferon-γ signature and a higher tumor infiltrating lymphocyte count compared with nonresponders.

In conclusion, nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab demonstrates antitumor activity in metastatic uveal melanoma. Results from this study and the Spanish GEM-1402 study indicate that this combination is active and should be considered for this patient population with otherwise limited options. Additional work is necessary to characterize the molecular and genomic signatures of responders and nonresponders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the patients and their families for participating in this study.

APPENDIX

FIG A1.

Percentage change in tumor burden from baseline over time. AE, adverse event.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented as a poster presentation with discussion at the 55th ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, May 31-June 4, 2019.

SUPPORT

Supported by Bristol Myers Squibb (S.P.P.) and The University of Texas MD Anderson High Impact Clinical Research Support Program (S.P.P.).

DISCLAIMER

Bristol Myers Squibb had a role in the study design but had no role in the data collection, analysis, interpretation of results, or the writing of this report.

CLINICAL TRIAL INFORMATION

NCT01585194 (PROSPER)

See accompanying editorial on page 554

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Sapna P. Patel

Administrative support: Patrick Hwu, Sapna P. Patel

Provision of study material or patients: Michael Shephard, Sapna P. Patel

Collection and assembly of data: Meredith S. Pelster, Dan S. Gombos, Michael Shephard, Liberty Posada, Maura S. Glover, Rinata Simien, Adi Diab, Patrick Hwu, Brett W. Carter, Sapna P. Patel

Data analysis and interpretation: Meredith S. Pelster, Stephen K. Gruschkus, Roland Bassett, Dan S. Gombos, Maura S. Glover, Rinata Simien, Adi Diab, Patrick Hwu, Brett W. Carter, Sapna P. Patel

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Metastatic Uveal Melanoma: Results From a Single-Arm Phase II Study

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Meredith S. Pelster

Honoraria: Castle Biosciences (I)

Dan S. Gombos

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AbbVie

Other Relationship: 3T Ophthalmic, Aura Biosciences

Adi Diab

Honoraria: Array BioPharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: Nektar, CureVac, Celgene, Idera

Research Funding: Nektar (Inst), Idera (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Merck, Apexigen

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Nektar

Patrick Hwu

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Immatics, Dragonfly Therapeutics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Dragonfly Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Immatics, Sanofi

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst)

Sapna P. Patel

Consulting or Advisory Role: Castle Biosciences, Cardinal Health

Speakers' Bureau: Merck

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Deciphera (Inst), Reata Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Provectus (Inst), InxMed (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Cardinal Health, Clinica Santa Maria, Merck

Other Relationship: Reata Pharmaceuticals, Immunocore

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh AD, Turell ME, Topham AK: Uveal melanoma: Trends in incidence, treatment, and survival. Ophthalmology 118:1881-1885, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin CC, Wu XC, Jemal A, et al. : Incidence of noncutaneous melanomas in the U.S. Cancer 103:1000-1007, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rietschel P, Panageas KS, Hanlon C, et al. : Variates of survival in metastatic uveal melanoma. J Clin Oncol 23:8076-8080, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai KK, Bollin KB, Patel SP: Obstacles to improving outcomes in the treatment of uveal melanoma. Cancer 124:2693-2703, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmer L, Vaubel J, Mohr P, et al. : Phase II DeCOG-study of ipilimumab in pretreated and treatment-naïve patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. PLoS One 10:e0118564, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshua AM, Monzon JG, Mihalcioiu C, et al. : A phase 2 study of tremelimumab in patients with advanced uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res 25:342-347, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Algazi AP, Tsai KK, Shoushtari AN, et al. : Clinical outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies. Cancer 122:3344-3353, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. : Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 381:1535-1546, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, et al. : Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 369:122-133, 2013. [Erratum: N Engl J Med 379:2185, 2018] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. : New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228-247, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvajal RD, Piperno-Neumann S, Kapiteijn E, et al. : Selumetinib in combination with dacarbazine in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma: A phase III, multicenter, randomized trial (SUMIT). J Clin Oncol 36:1232-1239, 2018. [Erratum: J Clin Oncol 36:3528, 2018] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khoja L, Atenafu EG, Suciu S, et al. : Meta-analysis in metastatic uveal melanoma to determine progression free and overall survival benchmarks: An International Rare Cancers Initiative (IRCI) ocular melanoma study. Ann Oncol 30:1370-1380, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]