PURPOSE:

Racial and ethnic minorities remain underrepresented in research and clinical trials. Better understanding of the components of effective minority recruitment into research studies is critical to understanding and reducing health disparities. Research on recruitment strategies for cancer-specific research—including colorectal cancer (CRC)—among African American men is particularly limited. We present an instrumental exploratory case study examining successful and unsuccessful strategies for recruiting African American men into focus groups centered on identifying barriers to and facilitators of CRC screening completion.

METHODS:

The parent qualitative study was designed to explore the social determinants of CRC screening uptake among African American men 45-75 years of age. Recruitment procedures made use of community-based participatory research strategies combined with built community relationships, including the use of trusted community members, culturally tailored marketing materials, and incentives.

RESULTS:

Community involvement and culturally tailored marketing materials facilitated recruitment. Barriers to recruitment included limited access to public spaces, transportation difficulties, and medical mistrust leading to reluctance to participate.

CONCLUSION:

The use of strategies such as prioritizing community relationship building, partnering with community leaders and gatekeepers, and using culturally tailored marketing materials can successfully overcome barriers to the recruitment of African American men into medical research studies. To improve participation and recruitment rates among racial and ethnic minorities in cancer-focused research studies, future researchers and clinical trial investigators should aim to broaden recruitment, strengthen community ties, offer incentives, and use multifaceted approaches to address specific deterrents such as medical mistrust and economic barriers.

BACKGROUND

Mortality from colorectal cancer (CRC) is 47% higher among non-Hispanic Black and African American men compared with non-Hispanic White men.1 It is vital that interventions are developed to increase CRC screening uptake in this population.

Low participation by African Americans in research and clinical trials is widely attributed to recruitment and retention barriers.2-10 Two systematic reviews5,9 found that the main barriers were medical mistrust, fear for safety, and concern about being a guinea pig. Historical events that have sown distrust between African Americans, researchers, and the medical community, such as the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis, are well documented9,11-18 and remain on the minds of African Americans today.7,9,19 African Americans believe that the risks of research participation are high and are not inclined to believe that researchers prioritize their well-being.5,7-9,20

Economic barriers (eg, lack of transportation, need for child care, and potential lost wages) are also significant obstacles to research participation for individuals of color.5,21,22 Methods of attenuating these burdens include offering monetary incentives or participation in a random prize drawing.3,10,23

Successful strategies for recruiting underrepresented minorities into research studies and clinical trials often incorporate cultural engagement and foster relationships and trust between research teams and minority communities through active community engagement.2,8,9,11,24-26 Respectful participant-researcher communication and transparency about research goals, intentions, and outcomes are key elements in removing the cultural, logistical, and social barriers that confound many researchers' well-intentioned efforts. Partnering with local communities, churches, and community-based organizations can help to overcome barriers of medical mistrust and fear for safety2,6,10,27-30 and build credibility and trust.4,5,8,9,31

Community-based participatory research is a multipronged approach to equitably involving researchers, community members, and others in research27,32 by establishing communities as full partners both in designing recruitment strategies and in the research itself.10,33 The community-based participatory research approach has achieved success in recruiting minority research participants; in one case, more than 300 African American participants, 52% of whom were male, were recruited into a CRC screening trial.26,27

To our knowledge, no published reports have specifically focused on strategies for recruiting African American men across multiple states for cancer-specific research. Because of variations in states' demographics (eg, smaller populations of African American men), multistate recruitment using community-based strategies may promote greater enrollment of diverse population subsets. Limitations to this approach, however, may include lack of time, personnel, and funds, and difficulty developing trusting relationships.34-36 Our research aimed to address this gap in the literature by analyzing the strategies used to recruit African American men to a qualitative study of attitudes to CRC screening.

METHODS

Design

We used an instrumental exploratory case-study design to examine the barriers to and facilitators of recruitment into a qualitative CRC screening-promotion study that used a comprehensive strategy to enroll African American men into 11 focus groups across three states. An instrumental exploratory case study seeks to use a particular case to provide a general understanding of a phenomenon by asking questions that are used to develop a framework.37-40

Parent Study

Rogers et al41 designed a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded qualitative study that sought to explore the social determinants of CRC screening uptake in African American men. Recruitment, data collection, and data analysis took place in 2019. In accordance with the NIH's Single Institutional Review Board (IRB) Policy for Multi-Site Research,42 the study was approved by the University of Utah IRB.

The IRB at the University of Utah approved the protocol of the parent study (IRB No. #00113679). Informed consent to participate was obtained from all study participants at the beginning of each focus-group session, and participants were informed that to ensure confidentiality, their names would be removed from their publishable quotes.

Eighty-four African American men were recruited (MN, n = 31; OH, n = 20; and UT, n = 33). Eligible participants self-identified as Black or African American; were 45-75 years of age; were born in the United States; spoke English; had a working telephone; and lived in MN, OH, or UT. As originally proposed by Rogers et al,43 the theoretically grounded focus-group questions stemmed from a Masculinity Barriers to [Medical] Care Scale developed by the current study principal investigator (PI).

Average per-session attendance was eight; sessions lasted an average of 75 minutes. Settings included libraries, barbershops, churches, and hotel conference rooms—where two to three research team members were present at each site. Each participant received a gift card of $20 in US dollars and the opportunity to enter a random prize drawing. Demographic information was collected anonymously at the conclusion of each focus group. The study protocol and findings have been published elsewhere.41,43

Data Sources and Process

We reviewed study correspondence and written documentation of procedures used in the parent study. We critically examined the participant recruitment approaches used, evaluated which were successful and unsuccessful, and explored possible reasons for success or lack thereof.

Analysis

In accordance with an instrumental case study, we examined the breadth of the recruitment procedures used and their observed outcomes and organized our findings according to emerging themes. We examined the processes preceding participant recruitment as well as the specific recruitment procedures used. Additionally, we provided the context for each to enhance understanding of the strategies used and delineate the grounds for our conclusions.

RESULTS

The parent study used a multipronged recruitment strategy that included developing culturally tailored marketing materials, collaborating with community-based organizations, and partnering with barbershops and churches.

Recruitment Strategies

Developing culturally appropriate marketing materials

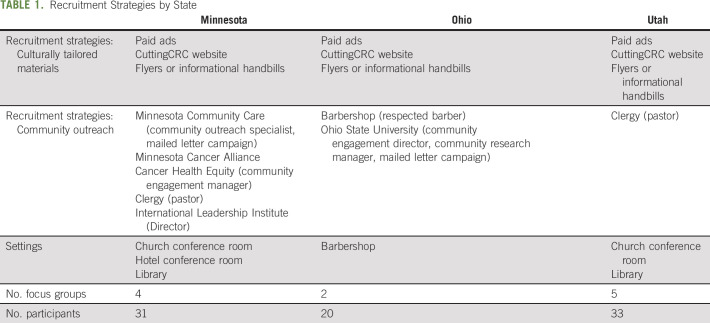

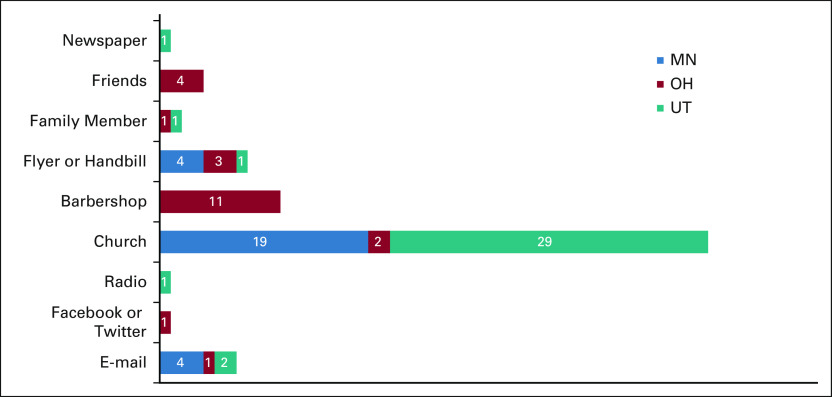

Culturally tailored marketing materials such as flyers, newspaper ads, and emails were developed that featured pictures of African American men with the caption “Did you know that Black/African American men have a 52% higher chance of dying from colon cancer compared to White men? Help us figure out why over conversation and food!” Participation requirements and incentives were described and contact information for and a photograph of the lead author (C.R.R., an African American male) provided. These materials were distributed via email, social media, and paid advertising (eg, newspaper ads). Table 1 provides a breakdown of the recruitment materials used in each state; Figure 1 depicts how participants reported hearing about the study.

TABLE 1.

Recruitment Strategies by State

FIG 1.

Marketing methods by which participants heard about the study, by state. MN, Minnesota; OH, Ohio; UT, Utah.

In Minnesota and Utah, culturally tailored materials were initially used to encourage study registration through a website described in ref. 45 that provided study details and linked to a participant registration form. The website was cocreated by the research team and members of Utah's African American community, and was later approved by the University of Utah IRB for research purposes.

Collaborating with community-based organizations

In Utah, the PI gave a presentation to Community Faces of Utah, a community advisory board comprising leaders from Utah's underserved populations, who provided feedback on the study's marketing materials. Community Faces of Utah's endorsement prompted neighborhood leaders to speak to their constituents about the study.

In Minnesota, the research team collaborated with a community-based health center, Minnesota Community Care, that had an extensive history of collaboration with public health researchers at the University of Minnesota, the PI's former employer. Its community outreach specialist was instrumental in creating informational handbills—small, culturally tailored handheld advertisements––and organizing a mail campaign that reached approximately 600 men who met the focus-group inclusion criteria. A University of Minnesota community engagement manager's connections with the Minnesota Cancer Alliance and Cancer Health Equity Network––two community organizations with which the PI previously held active membership—widened the effort's community reach. Partnerships with these entities were integral to successful recruitment to the Minnesota focus groups.

The team also partnered with Hennepin Healthcare, an acute-care hospital and clinic system in Minnesota's most diverse county, to send personalized invitations to participate to 1,500 eligible African American men and follow-up with participants until the day before their respective focus groups. Additionally, the team partnered with the International Leadership Institute, a community organization dedicated to strengthening intercultural communities. This partnership led to a successful collaboration between the study team and a respected Baptist church in Minnesota, where one of the focus groups was held.

Partnering with barbershops and churches

Collaboration with a respected barber (A.E.) was instrumental to the success of the Ohio focus groups; he helped to coordinate local recruitment and his barbershop hosted both Ohio groups. This connection stemmed from facilitation by a community engagement director (C.W.) and community research manager (A.M.) from Ohio State University.

In Utah and Minnesota, clergy helped to distribute recruitment posters and flyers to their own and other congregations, announced the focus groups from the pulpit, and provided space for the groups to meet following religious services. In Utah, most focus-group participants were recruited via clergy efforts.

Other Facilitators of Recruitment

Food was offered at each focus-group session and was chosen to avoid exacerbating health disparities; options were provided for individuals who informed the team of dietary restrictions. Many participants stated that they attended the focus groups because they knew food would be served.

Some of the best-attended focus groups were held in community barbershops or predominantly African American–serving churches immediately following Sunday services. These locations provided participants with a familiar setting where they were surrounded by trusted individuals, which may have increased their level of comfort in addressing potentially uncomfortable research questions.

Barriers to Recruitment

In Utah and Minnesota, challenges to finding suitable venues for the focus groups were a barrier. Initially, the sessions were held in libraries, but this proved difficult to sustain. Despite efforts to book months in advance, libraries had limited available meeting space. Some libraries would not allow food in the meeting space. Additionally, hours were curtailed on Saturdays, the day most focus-group participants were available.

Transportation difficulties were another barrier. Many participants' ability to attend was limited by distance or lack of transportation. Free public parking was limited in the urban locations most accessible to the target population. The research team did not provide participants with prepaid parking passes, a potential failed opportunity that might have alleviated this barrier.

The initial strategy to have participants in Minnesota and Utah register via the website described in ref. 45 was less successful than anticipated. Many men who provided phone numbers to be contacted by the research team never answered calls. Some phone numbers lacked voice-messaging service. Some men did not provide email addresses. Text messaging was not used because of high cost. Paid-media ads that were effective in previous studies conducted by the same research team46 were less fruitful this time, yielding just three of 84 participants (3.7%) at a disproportionately high cost.

Reliance on churches and clergy, although an important contributor to recruitment success, also presented some barriers. Many men attended church with their families. Scheduling the focus groups after church services resulted in transportation complications for some families and may have dissuaded some men from participating. Also, since the churches carried out extensive outreach promoting the focus groups, nonreligious African American men may have been deterred from participating, denying us access to an important subpopulation.

DISCUSSION

We describe the features of a qualitative CRC screening promotion study conducted across three states that resulted in exceptional enrollment of African American men. Our study supports the existing literature on the importance of trust between communities and research teams for the successful recruitment of African American men to research studies.9,10,44,47,48 Our experience further illustrates that medical mistrust remains a barrier to research participation by African American men.

Partially because of medical mistrust, some African American men were hesitant to participate in our no-known-risk study. When the team attempted to interest barbershops in Utah that predominantly serve African American men in hosting focus groups, barbers were apprehensive, cautious, and often disconnected the call after researchers said they were working with an NCI-designated cancer center. One barber mentioned the Tuskegee experiment and medical system mistrust as deterrents, whereas others acknowledged that recruitment of African American barbers would be difficult because they do not trust doctors.

To counter these negative perceptions, before and after calling the barbershops, the African American male PI and a White male research assistant visited the shops to get haircuts. All barbershops that gave the two research team members haircuts were willing to share information and discuss partnership opportunities, stressing the importance of relationship building to ameliorate medical mistrust among African American men.

Culturally tailored marketing materials (ie, paid-media ads, flyers, and posters) and the website described in ref. 45 were less successful in achieving interest in the study and trust in the research team than they had been in the team's previous research.49,50 The CuttingCRC website was initially chosen as a primary recruitment strategy because African Americans outpace all other racial and ethnic groups in smartphone use.51 However, compared with demographically similar White men, older African American men may have been less likely to have broadband service at home or to complete our online registration survey.52

Social media may have been a more fruitful outreach method had it been more formally used. Recruitment via social media has been effective with historically hard-to-reach populations including young cancer survivors46 as well as in smoking cessation research,53 and HIV vaccine clinical trials,54 among others. Social media can creatively reach populations that may not engage in conventional health services.55 In future studies, the use of these platforms may serve to break down barriers and aid recruitment.

Partnering with leaders and gatekeepers from churches and barbershops has been identified as an effective strategy for engaging minority participants in health interventions; these community spaces have proven to be excellent locations to deliver interventions to manage conditions such as hypertension and diabetes.30,56-59 Reliance on community relationships, including those with churches and other local organizations, is common in recruitment efforts.4,8,30,43 In the parent study, research team members' relationship building through attending worship services and engaging with congregants facilitated conducting focus groups in churches following services. Endorsements by local barbershops also boosted focus-group participation by establishing a basis of trust and attesting to the research team's commitment to the community.

Food was an important facilitator of recruitment. This incentive served to increase attendance––many participants commented that they attended because food was offered––and did not seem to adversely affect either participation or the thoughtfulness of discussions. Persistence in the effort to find venues that allowed food service ultimately proved crucial to recruitment success. The provision of culturally appropriate food that does not exacerbate health disparities and is sensitive to dietary restrictions can help focus-group discussions feel more inviting and may help to overcome barriers to trust by reinforcing that the researchers see the participants as people rather than as research subjects.5,9

The parent study did not measure the influence on recruitment of the monetary incentive and random prize drawing. However, considering how incentives have previously supported clinical trial recruitment and retention,60 they are potential recruitment facilitators that should be used to demonstrate that participants' time and opinions are valuable. Future researchers can enhance recruitment by offering both food and monetary incentives and using study locations that permit food service.

Another critical aspect of successful recruitment efforts was focus-group location. Considering both possible economic burdens and participants' comfort levels, it was important that the groups meet in locations convenient for the participants. Some of the best-attended focus groups took place in community barbershops or following services in predominantly African American churches. Possible reasons for this are that in these locations participants felt at ease among people they trusted, which encouraged them to engage. Location convenience may also have eased economic burdens, which as our study––consistent with previous published studies––found were barriers to participation5,21,61 (eg, lack of transportation and absence of free parking).

The research team's involvement of community leaders was based on the PI's previous successful recruitment efforts as well as on community feedback received before the launch of the parent study. Demonstrating true commitment to reducing health inequities and intentionally fostering long-term relationships with communities is key for future researchers and clinical trial investigators aiming to deploy similar efforts. Overcoming barriers can be challenging, and adjustments to initial strategies may be necessary. Long-term relationships with communities also may permit researchers to introduce new recruitment strategies if necessary.

Trustworthiness remains a key factor in both recruitment and study participation. Griffith et al62 qualitatively examined the influence of trustworthiness in the conduct of medical research, concluding that establishing trust goes beyond overcoming perceived medical mistrust. In particular, participants consider researchers' knowledge and passion for the research project when determining trustworthiness. Our PI's expertise, knowledge, and passion were evident in his dedication to the research despite the time commitment required to invest in community relationships. Also (as in the team's previous studies41), the PI conducted follow-up community dialogues (with free food and free parking) to discuss focus-group findings. These dialogues served to both augment community trust and obtain the community's feedback on next research steps.

Finally, minority communities remain largely skeptical of researchers' motives and goals, especially when researchers are exclusively White.41 The mindset that researchers and clinical trial investigators do not prioritize minority communities' best interests perpetuates the mistrust stemming from the historical mistreatment of African Americans in medical research.12-18 Focus-group participants commented that including the face of the lead author—an African American man with a doctoral degree—in culturally tailored flyers played a critical role in encouraging trust.

Several limitations are worthy of note. First, recruitment strategies were solely focused on African American men. The importance of this unique focus is reinforced, however, by a recent review of participation by minorities and women in oncology clinical trials,63 which found that African Americans remain underrepresented in these research studies. Second, our study design centered on recruitment to focus groups rather than to cancer clinical trials. Medical mistrust and fear-for-safety barriers may be more common in recruitment for clinical studies in which new drugs or diagnostic procedures are being tested. Greater understanding of such barriers is needed to better inform recruitment strategies for such studies. Finally, qualitative studies such as this one typically use a face-to-face data-collection approach that depends on participants' willingness to share information and experiences and thus may limit data completeness.64 Conversely, the parent study's success in recruiting participants into 11 focus groups demonstrates the strength of the recruitment process.

In conclusion, this study advances the literature on the recruitment of hard-to-reach African American men by (1) reinforcing the importance of gaining the support and active involvement of community leaders and (2) identifying the most successful settings in which to conduct qualitative research with African American men.

To overcome barriers to the recruitment of African American men into medical research studies, investigators should strive to determine the level of medical mistrust and trustworthiness barriers present, and should consider adopting strategies such as expanding recruitment to more than one state and building relationships with community leaders. The successes and lessons learned from this study may help to inform minority recruitment strategies for future clinical and community-based research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors extend gratitude to the participants who made the study possible and acknowledge Eleanor Mayfield and Nana Mensah, who provided editorial assistance. The successful implementation of this study would also not have been possible without support from Angela Holtquist, Calvary Baptist Church, the Cancer Health Equity Network, DAPD, D-Brand Designs, Greater Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, Huntsman Cancer Institute, Minnesota Community Care, and the Center for Cancer Health Equity at Ohio State University. The authors have obtained permission to acknowledge all those mentioned here.

Michael D. Fetters

Honoraria: Medical Cyberworlds Inc

Other Relationship: Medical Cyberworlds Inc

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, University of Utah, or Huntsman Cancer Institute.

SUPPORT

Supported by the NCI of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Grant K01CA234319, 5 For the Fight, the V Foundation for Cancer Research, University of Utah School of Medicine, and Huntsman Cancer Institute. These funding bodies played no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the writing of the manuscript.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at DOI https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.21.00008.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Charles R. Rogers, Michael D. Fetters

Financial support: Charles R. Rogers

Administrative support: Alicia McKoy

Provision of study materials or patients: Alicia McKoy, Al Edmonson

Collection and assembly of data: Charles R. Rogers, Phung Matthews, Nathan Le Duc, Alicia McKoy, Al Edmonson

Data analysis and interpretation: Charles R. Rogers, Phung Matthews, Ellen Brooks, Nathan Le Duc, Chasity Washington, Michael D. Fetters

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Barriers to and Facilitators of Recruitment of Adult African American Men for Colorectal Cancer Research: An Instrumental Exploratory Case Study

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Michael D. Fetters

Honoraria: Medical Cyberworlds Inc

Other Relationship: Medical Cyberworlds Inc

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society : Colorectal Cancer Facts 2020. Atlanta, GA, ACS. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2020-2022.pdf, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stallings FL, Ford ME, Simpson NK, et al. : Black participation in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial. Control Clin Trials 21:379S-389S, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatchett BF, Holmes K, Duran DA, et al. : African Americans and research participation: The recruitment process. J Black Stud 30:664-675, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knobf MT, Juarez G, Lee SY, et al. : Challenges and strategies in recruitment of ethnically diverse populations for cancer nursing research. Oncol Nurs Forum 34:1187-1194, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. : Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: A systematic review. Cancer 112:228-242, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swanson GM, Ward AJ: Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: Toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 87:1747-1759, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, et al. : Attitudes and beliefs of AA toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med 14:537-546, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uybico SJ, Pavel S, Gross CP: Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: A systematic review of recruitment interventions. J Gen Intern Med 22:852-863, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George S, Duran N, Norris K: A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. AM J Public Health 104:e16-e31, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes TB, Varma VR, Pettigrew C, et al. : African Americans and clinical research: Evidence concerning barriers and facilitators to participation and recruitment recommendations. Gerontologist 57:348-358, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK: Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health 27:1-28, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy BR, Mathis CC, Woods AK: African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: Healthcare for diverse populations. J Cult Divers 14:56-60, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suite DH, La Bril R, Primm A, et al. : Beyond misdiagnosis, misunderstanding and mistrust: Relevance of the historical perspective in the medical and mental health treatment of people of color. J Natl Med Assoc 99:879-885, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, et al. : More than Tuskegee: Understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved 21:879-897, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaiswal J: Whose responsibility is it to dismantle medical mistrust? Future directions for researchers and health care providers. Behav Med 45:188-196, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alsan M, Wanamaker M: Tuskegee and the health of black men. Q J Econ 133:407-455, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brandon DT, Isaac LA, LaVeist TA: The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: Is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? J Natl Med Assoc 97:951-956, 2005 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen BR, Hodgson NA, Gitlin LN: It's a matter of trust: Older African Americans speak about their health care encounters. J Appl Gerontol 35:1058-1076, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammonds EM, Reverby SM: Toward a historically informed analysis of racial health disparities since 1619. Am J Public Health 109:1348-1349, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford ME, Havstad SL, Davis SD: A Randomized trial of recruitment methods for older African American men in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial. Clin Trials 1:343-351, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royal C, Baffoe-Bonnie A, Kittle R, et al. : Recruitment experience in the first phase of the African American Hereditary Prostate Cancer (AAHPC) study. Ann Epidemiol 10:S69-S77, 2000. (suppl 8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivers D, August EM, Sehovic I, et al. : A systematic review of factors influencing African Americans' participation in cancer clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials 35:13-32, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang R, Kelkar VA, Byrd JR, et al. : African American participation in health-related research studies: Indicators for effective recruitment. J Public Health Manag Pract 19:110-118, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paskett ED, Degraffinreid C, Tatum CM, et al. : The recruitment of African Americans to cancer prevention and control studies. Prev Med 25:547-553, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones RA, Steeves R, Williams I: Strategies for Recruiting African American men into prostate screening studies. Nurs Res 58:452-456, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greiner KA, Friedman DB, Adams SA, et al. : Effective recruitment strategies and community-based participatory research: Community networks program centers' recruitment in cancer prevention studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 23:416-423, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis SN, Govindaraju S, Jackson B, et al. : Recruitment techniques and strategies in a community-based colorectal cancer screening study of men and women of African ancestry. Nurs Res 67:212-221, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis EM, Erwin DO, Jandorf L, et al. : Designing a randomized controlled trial to evaluate a community-based narrative intervention for improving colorectal cancer screening for African Americans. Contemp Clin Trials 65:8-18, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel YR, Carr KA, Magjuka D, et al. : Successful recruitment of healthy African American men to genomic studies from high-volume community health fairs: Implications for future genomic research in minority populations. Cancer 118:1075-1082, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saunders DR, Holt CL, Le D, et al. : Recruitment and participation of African American men in church-based health promotion workshops. J Community Health 40:1300-1310, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heiat A, Gross CP, Krumholz HM: Representation of the elderly, women, and minorities in heart failure clinical Trials. Arch Intern Med 162:1682-1688, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Israel Ba, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. : Community-based participatory research: Policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health (Abington) 14:182-197, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeJonckheere M, Linquist-Grantz R, Toraman S, et al. : Intersection of mixed methods and community-based participatory research: A methodological review. J Mix Methods Res 13:481-502, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmons RG, Yuan-Chin AL, Stroup AM, et al. : Examining the challenges of family recruitment to behavioral intervention trials: Factors associated with participation and enrollment in a multi-state colonscopy intervention trial. Trials 14:116, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayek M, Mackie TI, Mulé CM, et al. : A multi-state study on mental health evaluation for children entering foster care. Adm Policy Ment Health 41:552-567, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gohagan JK, Broski K, Gren LH, et al. : Managing multi-center recruitment in the PLCO cancer screening trial. Rev Recent Clin Trials 10:187-193, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kähkönen AK: Conducting a case study in supply management. Operations Supply Chain Manag Int J 4:31-41, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harling K: An overview of case study. SSRN Electron J, 2012. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2141476 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zainal Z: Case study as a research method. J Kemanusiaan 5, 2007. https://jurnalkemanusiaan.utm.my/index.php/kemanusiaan/article/view/165 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, et al. : The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 11:100, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogers CR, Rogers TN, LeDuc N, et al. : Social determinants of colorectal cancer screening uptake among African-American men: Understanding the role of masculine role norms, medical mistrust, and normative support. Ethn Health, 10.1080/13557858.2020.1849569 [epub ahead of print on November 29, 2020] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Institutes of Health : Single IRB Policy for Multi-Site Research. https://grants.nih.gov/policy/humansubjects/single-irb-policy-multi-site-research.htm, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers CR, Okuyemi K, Paskett ED, et al. : Study protocol for developing #CuttingCRC: A barbershop-based trial on masculinity barriers to care and colorectal cancer screening uptake among African-American men using an exploratory sequential mixed-methods design. BMJ Open 9:e030000, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abernethy AD, Magat MM, Houston TR, et al. : Recruiting African American men for cancer screening studies: Applying a culturally based model. Health Educ Behav 32:441-451, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.#CuttingCRC. CuttingCRC.com

- 46.Gorman JR, Roberts SC, Dominick SA, et al. : A diversified recruitment approach incorporating social media leads to research participation among young adult-aged female cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 3:59-65, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ibrahim S, Sidani S: Strategies to recruit minority persons: A systematic review. J Immigr Minor Health 16:882-888, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wallington SF, Dash C, Sheppard VB, et al. : Enrolling minority and underserved populations in cancer clinical research. Am J Prev Med 50:111-117, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Halcomb EJ, Gholizadeh L, DiGiacomo M, et al. : Literature review: Considerations in undertaking focus group research with culturally and linguistically diverse groups. J Clin Nurs 16:1000-1011, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferdinand DP, Nedunchezhian S, Ferdinand KC: Hypertension in African Americans: Advances in community outreach and public health approaches. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 63:40-45, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Multifaceted Connections: African-American Media Usage Outpaces Across Platforms. http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2015/multifaceted-connections-african-american-media-usage-outpaces-across-platforms.html, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 52.African Americans and Technology Use: A Demographic Portrait. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2014/01/African-Americans-and-Technology-Use.pdf, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frandsen M, Walters J, Ferguson SG: Exploring the viability of using online social media advertising as a recruitment method for smoking cessation clinical trials. Nicotine Tob Res 16:247-251, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sitar S, Hartman BI, Graham BS, et al. : Social media as a tool for engaging and educating audiences around HIV vaccine research and clinical trial participation. Retrovirology 6:218, 2009. (suppl 3) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clarke J, Van Amerom G: A comparison of blogs by depressed men and women. Issues Ment Health Nurs 29:243-264, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Linnan LA, D'Angelo H, Harrington CB: A literature synthesis of health promotion research in salons and barbershops. Am J Prev Med 47:77-85, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Satin RW, Williams LB, Dias J, et al. : Community trial of a faith-based lifestyle intervention to prevent diabetes among African-Americans. J Community Health 41:87-96, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schoenthaler AM, Lancaster KJ, Chaplin W, et al. : Cluster randomized clinical trial of FAITH (Faith-Based Approaches in the Treatment of Hypertension) in blacks main trial results. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 11:e004691, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rogers CR, Goodson P, Dietz LR, et al. : Predictors of intention to obtain colorectal cancer screening among African American men in a state fair setting. Am J Mens Health 12:851-862, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parkinson B, Meacock R, Sutton M, et al. : Designing and using incentives to support recruitment and retention in clinical trials: A scoping review and a checklist for design. Trials 20:624, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brown DR, Fouad MN, Basen-Engquist K, et al. : Recruitment and retention of minority women in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment trials. Ann Epidemiol 10:S13-S21, 2000. (8 suppl) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Griffith DM, Cornish Jaeger E, Bergner E, et al. : Determinants of trustworthiness to conduct medical research: Findings from focus groups conducted with racially and ethnically diverse adults. J Gen Intern Med 35:2669-2975, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duma N, Aguilera JV, Paludo J, et al. : Representation of minorities and women in oncology clinical trials: Review of the past 14 years. J Oncol Pract 14:e1-e10, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu M: Data collection mode differences between national face-to-face and web surveys on gender inequality and discrimination questions. Womens Stud Int Forum 60:11-16, 2017 [Google Scholar]