PURPOSE:

To determine patient and disease characteristics associated with functional disability among adults with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

METHODS:

In a prospective cohort of participants newly diagnosed with advanced NSCLC and beginning systemic treatment, functional disability in usual activities, mobility, and self-care was measured using the EuroQol-5D-5L at baseline. Demographics, comorbidities, brain metastases, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), and psychologic variables (depression [Patient Health Questionnaire-9] and anxiety [Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale]) were captured. Patients were classified into two disability groups (none-slight or moderate-severe) on the basis of total functional status scores. Differences between disability groups were determined (chi-square and t tests). Associations between patient characteristics and baseline disability were assessed using logistic regression.

RESULTS:

Among 173 participants, mean age was 63.3 years, 56% were male, 83% had ECOG PS 0-1, and 41% had brain metastases. Baseline disability was present in 39% of participants, with patients having moderate to severe disability in usual activities (37.6%), mobility (26.6%), and self-care (5.2%). Depressive and/or anxiety symptoms ranged from none to severe (Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale M = 6.5, SD = 5.3). Depressive symptoms were the only characteristic associated with a higher odds of baseline disability (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.38; P < .001). Participants with poorer ECOG PS (aOR: 4.64; 95% CI, 1.84 to 11.68; P = .001) and depressive symptoms (aOR: 1.15; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.24; P < .001) had higher odds of moderate-severe mobility disability compared with the none-slight disability group.

CONCLUSION:

More than one third of all adults with advanced NSCLC have moderate-severe functional disability at baseline. Psychologic symptoms were significantly associated with moderate-severe baseline disability.

INTRODUCTION

Non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung cancer diagnosed among adults.1 It is the number one cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality and kills more men and women in the United States than breast, prostate, and colon cancer combined.2 Many older adults with chronic disease, including cancer, prioritize remaining independent in functional status activities (ie, no disability) over survival.3 The development of disability, defined as impairment in functional status, is a key patient-reported outcome that is understudied, as both an end point and a correlative finding in oncology clinical trial research.4

Across cancer types, few studies have evaluated disability at baseline prior to treatment initiation and over time during cancer treatment.5 Studies typically use patient-reported measures of functional status, and currently there is no gold standard measure. Because of a dearth of data and variability in the definition and measurement of disability for patients with advanced lung cancer, there is no general understanding of baseline disability among these patients, including knowledge of patient risk factors for disability. Patients even with advanced disease at diagnosis are living longer, often years, with novel treatments such as immunotherapy and targeted treatments,6 solidifying the need for the evaluation of functional disability.

It is important to identify patient characteristics associated with baseline disability such that necessary resources are provided early, perhaps even before or concomitant with new immunotherapy and targeted treatments.7 Adults with stage IV NSCLC and increasing age experience more symptom distress and functional impairment as compared with patients with other cancer types during treatment.8,9 Furthermore, patient characteristics associated with functional disability after a new cancer diagnosis include depressive symptoms and poor physical capability.10,11 Existing literature demonstrates an association of depression and anxiety symptoms with lung cancer symptom severity,12 physician-rated performance status,13 and overall survival14 but no specific association with functional status measures or the presence of baseline disability. Whether age and other patient and disease-related characteristics are associated with functional disability at baseline, specifically among older versus younger adults with advanced NSCLC, is unknown.

The objectives of this study were two-fold: first, to describe disability among older versus younger adults with advanced NSCLC in the era of immuno-oncology and precision medicine and second, to evaluate factors associated with baseline disability. We hypothesized specific patient demographics, particularly older age, disease-related variables (ie, brain and bone metastases), and psychologic variables (ie, depressive or anxiety symptoms and stress) would be associated with increased functional disability.

METHODS

Study Sample

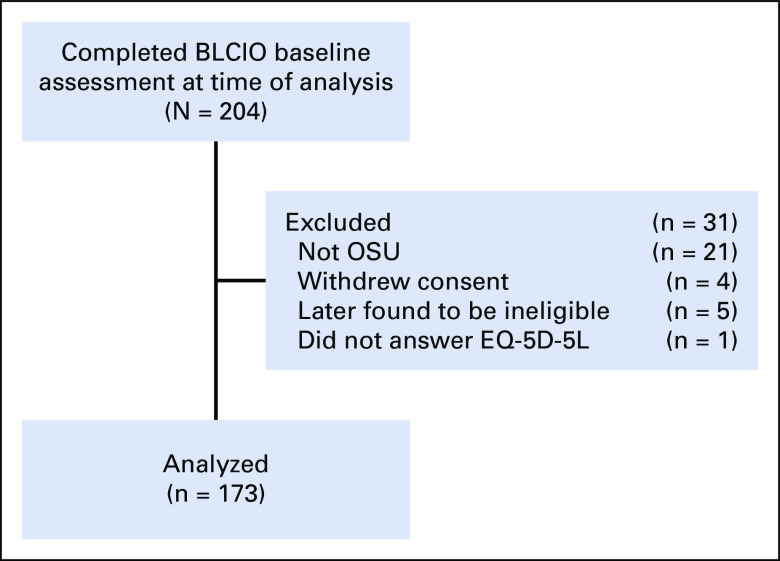

Patients (n = 173) enrolled at diagnosis into the Beating Lung Cancer in Ohio study, an ongoing prospective cohort study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03199651). Participants were enrolled from June 2017 through October 2019 and accrued from the Thoracic Oncology Clinic at The Ohio State University (OSU), a National Cancer Institute–designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. Participants were eligible if they were English-speaking and age ≥ 18 years and with newly diagnosed stage IV NSCLC confirmed by pathology report, staging confirmed by imaging and/or pathology report, within 4 weeks of their first-line treatment regimen, willing to provide access to medical records, provide biospecimens, and respond to self-report measures either in-person or by telephone interview. Participants could have any Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) and any level of comorbidity. Participants were excluded if they received treatment with definitive chemoradiotherapy; received treatment for stage IV NSCLC for over 4 weeks before enrollment; had baseline survey completed more than 40 days after treatment start; and/or had the presence of disabling hearing, vision, or psychiatric impairment preventing consent or completion of self-report measures in English. Patients were excluded if they were not patients at OSU, withdrew consent, were later found to be ineligible, or did not complete the EuroQol-5D-5L (EQ-5D-5L) at baseline, resulting in a total sample size of 173 participants.

Data Collection

The Institutional Review Board of OSU approved the study and all procedures in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants completed written informed consent. Consent was completed by research personnel in the clinic at the time of first appointment with a thoracic oncologist. Within 2 weeks of enrollment, patients were contacted through telephone by independent, trained interviewers who conducted the assessment of patient-reported outcomes. Initial assessments included demographics (age, sex, and zip code to determine urban or rural living), patient-reported depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale [PHQ-9]15), anxiety symptoms (Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale [GAD-7]16), cancer-specific stress (Impact of Events Scale-Revised [IES-R]17,18), and functional status (EQ-5D-5L19).

The presence of brain and/or bone metastases was used as an indicator of disease severity and was abstracted from participants' electronic medical records baseline imaging reports by study personnel. Medical comorbidities were documented by query of International Classification of Diseases 10th revision codes corresponding to diagnoses in the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)20,21 that occurred at any time prior to advanced NSCLC diagnosis. Modified CCI scores, excluding the six points because of metastatic cancer, were used. Individuals from rural settings have reported disability at higher rates than those from urban settings.22 Therefore, 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes23 were used to categorize patients into a rural or urban living setting on the basis of their county of residence.

Outcome Variables

Disability

Disability was assessed with the three functional items from the validated EQ-5D-5L19 survey: self-care, usual activities, and mobility (modified [m]EQ-5D-5L). Each item was rated by participants on a 5-point Likert scale, that is, 0 (no problems), 1 (slight problems), 2 (moderate problems), 3 (severe problems), and 4 (unable to do). The EQ-5D-5L has been mapped to the EORTC-QLQ-C30,24 specifically among patients with advanced NSCLC.25 The EQ-5D-5L consists of a five-item descriptive system and a one-item visual analogue scale. The pain and anxiety and/or depression questions were captured but excluded from the total score as they would add unwanted variance in the functional disability items and to disentangle functional disability from the psychologic symptom measures (see Covariates). Summing the three items, the total score ranged from 0 to 12, a higher score indicating greater disability.26 For the primary disability outcome, patients were classified into one of two disability groups (moderate-severe versus none-slight) on the basis of the total three-item score, similar to previous analytic approaches by Presley et al.10 The secondary disability outcomes describe disability within each functional activity type: self-care, usual activities, and mobility (see Statistical Analysis).

Covariates

Depressive symptoms

The PHQ-915 was used as recommended by ASCO27 to evaluate depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 has nine items scored on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The total score ranges from 0 to 27, with higher values indicating higher depressive symptoms. Symptom-level classes are 0-7 = none to mild, 8-14 = moderate, 15-19 = moderate to severe, and 20-27 = severe.15 Participants were also asked about any prior diagnosis of major depressive disorder.

Anxiety symptoms

The GAD-716 was used as recommended by ASCO.27 Anxiety symptoms over the previous month are rated on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Items are totaled, ranging from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety. Symptom-level classes are none to mild = 0-9, moderate = 10-14, and moderate to severe or severe = 15-21.16

Cancer-specific stress

The IES-R17,18 assesses cancer-specific stress (eg, intrusive thoughts about the disease, avoidant thoughts and/or behaviors, and hyperarousal) present in the past week. The IES-R is a 22-item measure scored on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Items are totaled; the total score can range from 0 to 64, with higher scores indicating more severe stress.

Performance status

ECOG PS score28 was assigned by the treating physician. ECOG PS can range from 0 to 5, with the following classifications: 0 = fully active, able to carry on all predisease performance without restriction; 1 = restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature; 2 = ambulatory and capable of all self-care, up and about more than 50% of waking hours, but unable to carry out any work activities; 3 = capable of only limited self-care, confined to bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours; 4 = completely disabled, cannot carry out any self-care, totally confined to bed or chair; 5 = deceased.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was restricted to patients with complete baseline data on the EQ-5D-5L (n = 173 [84.8%] of N = 204, Fig 1). To quantify functional disability, we summed the mEQ-5D-5L. To ensure the validity of the mEQ-5D-5L, a Pearson's correlation between the five-item and three-item version was r = 0.93. Patients were then classified into one of two disability groups. Patients reporting 0 (no problems) or 1 (slight problems) for each item (ie, usual activities, mobility, and self-care) were placed in the none-slight disability group. Patients reporting two (moderate problems) or higher on any functional activity comprised the moderate-severe disability group. The overall moderate-severe disability group included patients in the moderate-severe disability group for at least one of the three subscales.

FIG 1.

Patient flow diagram. BLCIO, Beating Lung Cancer in Ohio; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5D-5L; OSU, Ohio State University.

Patient demographic and treatment-related characteristics were summarized by age (age ≥ 60 years v < 60 years) and disability group (none-slight v moderate-severe). Consistent with prior research,10,11 the age cutoff was chosen and appropriate within the contexts of higher comorbidity and lower socioeconomic status, found within Ohio and Appalachian regions of the United States.29-31 Categorical variables were summarized as proportions and compared by Fisher's exact tests. Continuous variables were summarized as means and standard deviations and compared by t tests. The Benjamini-Hochberg method was used for multiple testing corrections across all three sets of tests between disability groups, setting the false discovery rate at 5% (q).32 This method controls for the expected proportion of falsely rejected hypotheses while maintaining statistical power.

Using logistic regression models, we assessed bivariate associations between patient and cancer, clinical and psychologic variables, and disability outcomes. For the final adjusted models, only covariates with a bivariate P value < .2 were retained. To avoid model overfitting and multicollinearity, adjusted models were constrained to only one psychologic measure, PHQ-9, as it had the strongest relationship with the disability outcome based on bivariate analyses. Multivariable logistic models included these final variables. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were calculated for moderate-severe versus none-slight disability. C-statistics were calculated to evaluate the goodness of fit of the multivariable logistic regression models and to summarize model discrimination. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R version 3.6.1. A P value or q value of < .05 was used to determine statistically significant results. The q values denote the Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P values from exact chi-square or t tests for categorical or continuous variables, respectively.

RESULTS

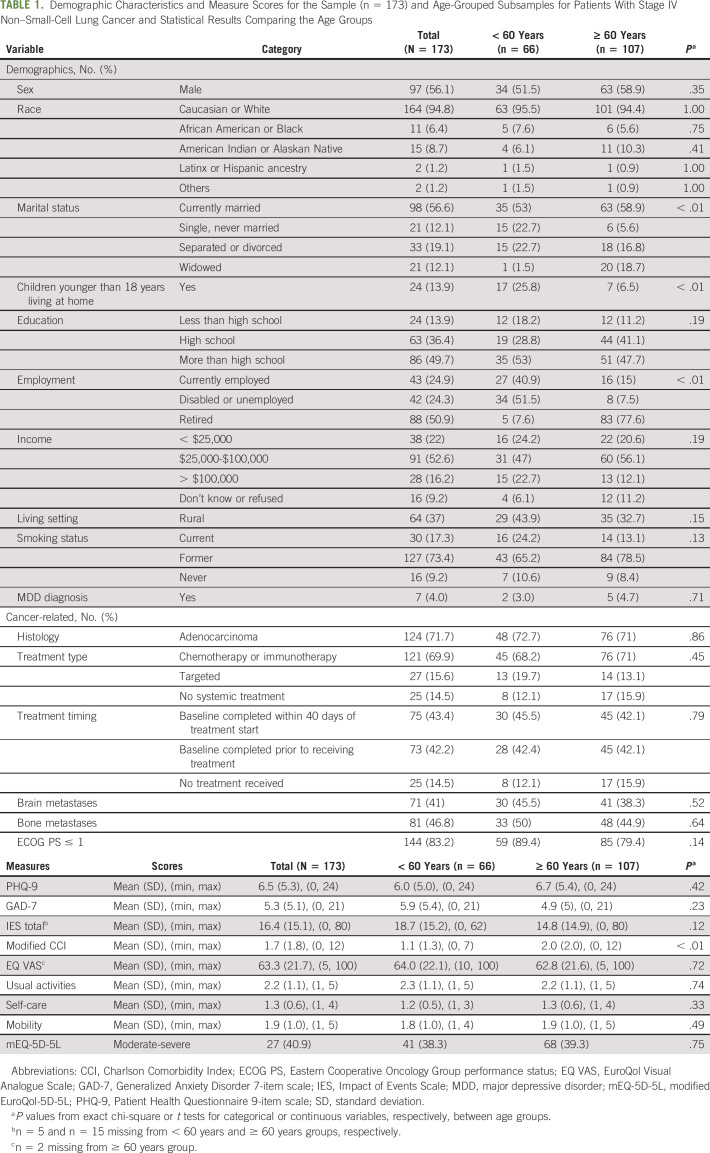

Table 1 provides the demographic, clinical, and psychologic characteristics of the total sample (n = 173) and by age group. The average age of patients was 63.3 years (SD = 11.3; range, 34-92 years), with 56% male, 37% rural, 17% ECOG PS ≥ 2, and 41% with brain metastases at baseline. The median score for the full sample was 2 (range, 0-9). The median three-item score for the none-slight disability group was 1 (range, 0-5), whereas the median score for the moderate-severe disability group was 4 (range, 2-9). A higher percentage of older adults had worse ECOG PS (P = .139) and a higher CCI score (P = .001; Table 1). The mean EQ Visual Analogue Scale score was 63, with no patients reporting a score of 0 and 5% reporting a score of 100. The majority of patients received their baseline survey prior to or within 7 days of treatment start (58%). Total disability scores did not significantly vary by age, sex, rural or nonrural living, or CCI (data not shown). All variables with missing data are indicated in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Measure Scores for the Sample (n = 173) and Age-Grouped Subsamples for Patients With Stage IV Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Statistical Results Comparing the Age Groups

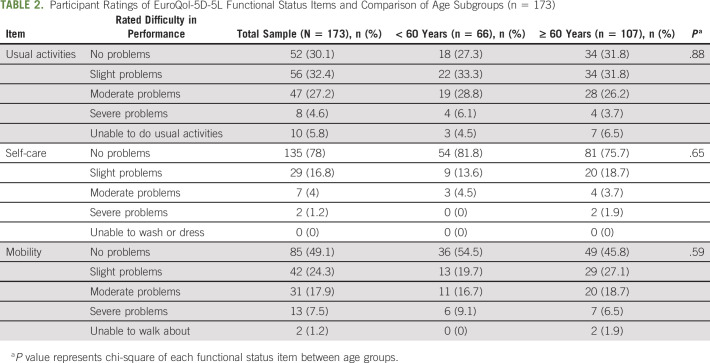

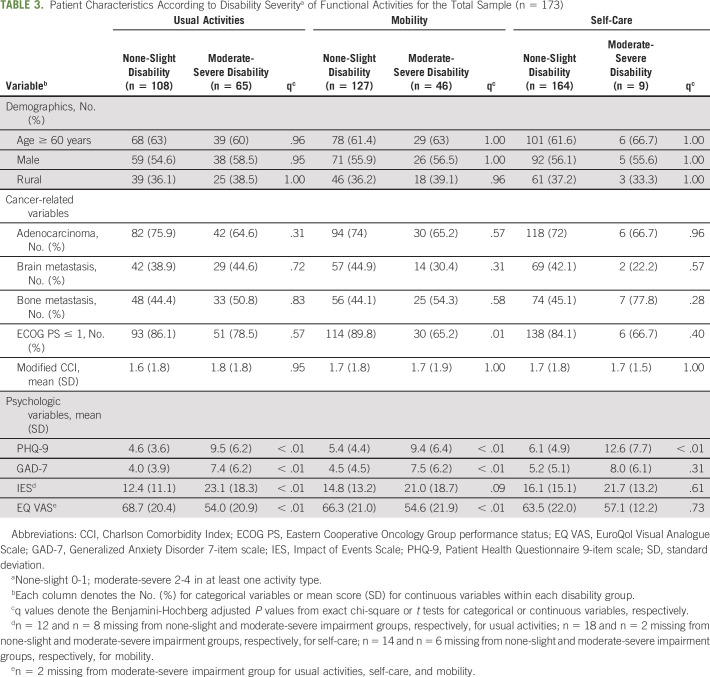

Table 2 provides all mEQ-5D-5L subscale responses for the sample and by age group. Overall, disability was present in 39% of participants. Moderate-severe disability was reported in usual activities (37.6%), mobility (26.6%), and self-care (5.2%). Participants with moderate-severe disability reported significantly higher depressive and anxiety symptoms (P < .001) as compared with the none-slight disability group. Table 3 shows depression, anxiety, and cancer-specific stress (IES) scores for the total sample and the associations between these scores and each type of functional activity (with the exception of IES and GAD-7 for self-care). ECOG PS was associated with severe mobility disability (P = .001).

TABLE 2.

Participant Ratings of EuroQol-5D-5L Functional Status Items and Comparison of Age Subgroups (n = 173)

TABLE 3.

Patient Characteristics According to Disability Severitya of Functional Activities for the Total Sample (n = 173)

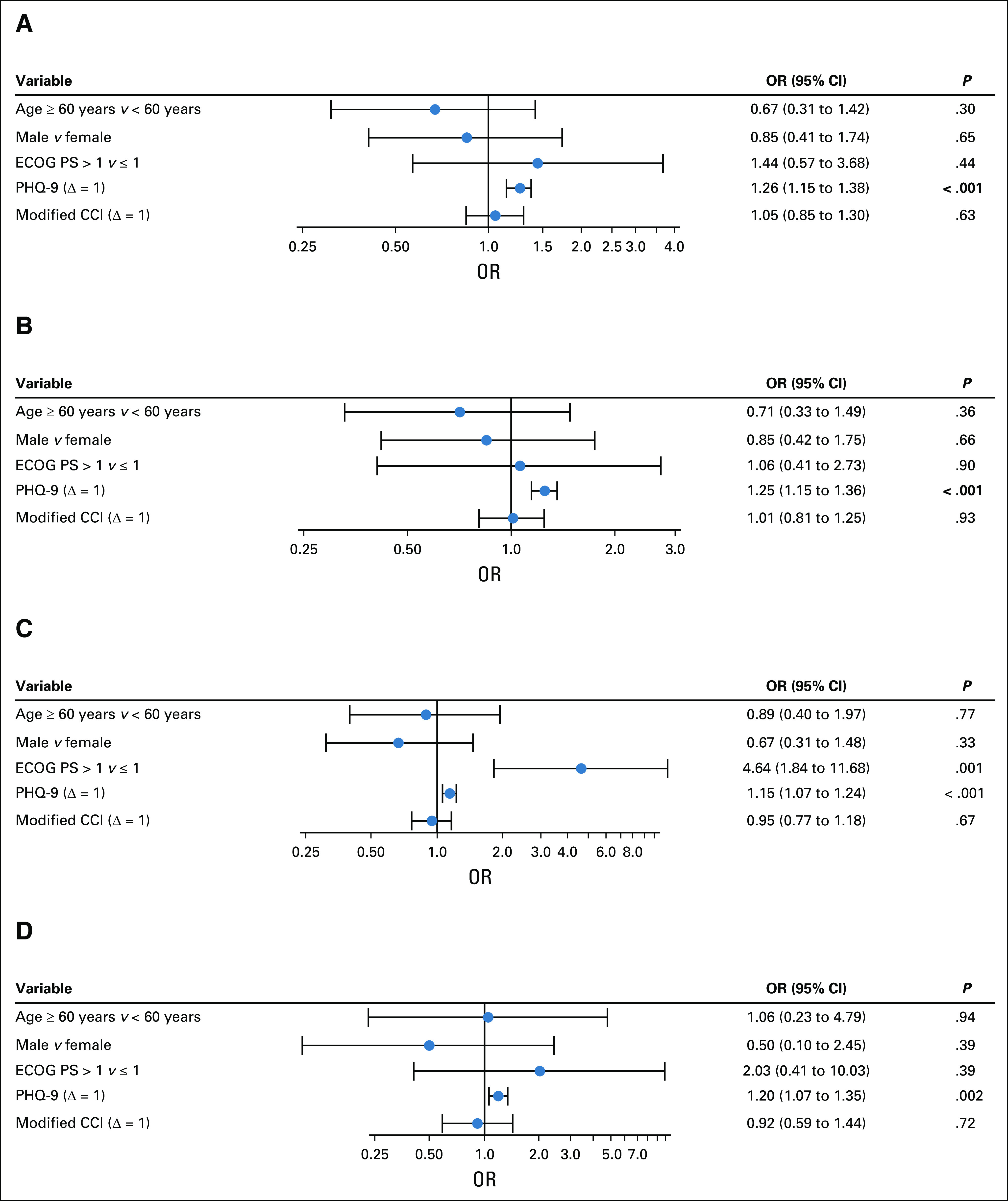

Figure 2 demonstrates the ORs from adjusted models for moderate-severe disability on the basis of mEQ-5D-5L classification. After adjusting for age, sex, and CCI score, depressive symptoms (OR: 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.38; P < .001) were significantly associated with moderate-severe baseline disability (Fig 2A). Both higher baseline depressive symptoms (OR: 1.15; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.24; P < .001) and higher ECOG PS score (OR: 4.64; 95% CI, 1.84 to 11.68; P = .001) were significantly associated with moderate-severe mobility disability (Fig 2C). Depressive symptoms were also significantly associated with moderate-severe baseline disability in usual activities (OR: 1.25; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.36; P < .001) and self-care (OR: 1.20; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.35; P = .002; Fig 2B). All four models (Figs 2A-2D) showed good discrimination with C-statistics of 0.76, 0.74, 0.75, and 0.78, respectively.

FIG 2.

(A) Forest plot for moderate-severe disability on the basis of EuroQol-5D-5L total (adjusted models). (B-D) Forest plot of ORs (95% CI; log scale) for moderate-severe disability on the basis of three EuroQol functional status items: (B) usual activities (adjusted models), (C) mobility (adjusted models), and (D) self-care (adjusted models). OR calculations are based on adjusted logistic regression models. Covariates included age, sex, ECOG PS, PHQ-9, and modified CCI score. CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; OR, odds ratio; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale.

DISCUSSION

Among 173 participants with stage IV NSCLC, more than one-third reported disability within 4 weeks of cancer treatment initiation. More than 30% of patients had moderate to severe disability in usual activities and more than 25% in mobility. A higher percentage of older adults had a worse ECOG PS (more than 20%) and a higher number of comorbidities. There was no significant difference between psychologic health scores by age group. After adjusting for demographic and clinical variables, a worse ECOG PS was associated with moderate-severe disability in mobility. Depressive and anxiety symptoms and cancer-related stress were significantly higher in those with moderate-severe disability in each functional activity type. Despite low self-reported history of depression (4%), psychologic symptoms were present. This is consistent with prior literature demonstrating an association between depressive and anxiety symptoms and disability in a variety of cancer types.33

This is one of the first studies to highlight a significant association between psychologic symptoms and baseline disability among adults with stage IV NSCLC, regardless of comorbid conditions and lung cancer characteristics, in the era of immunotherapy and precision medicine. Among patients with cancer, depression, anxiety, and stress are associated with negative outcomes such as poor quality of life, greater functional impairment and disability, and increased mortality.34-36 In advanced breast cancer, for example, poor functional capacity and depression are associated with disability and impaired quality of life.37 The present study demonstrates that this relationship is also present at baseline for patients with lung cancer within 4 weeks of treatment initiation, even with the newest available cancer treatments.

This is one of the largest studies comparing functional disability among older versus younger adults with advanced NSCLC. In studies of older adults, the lower bound for studying age has varied from 60 to 70 years, and the majority of studies have been conducted outside the United States.4,38,39 One of the largest studies conducted within the United States included patients of all cancer types (N = 300) and used the Short Form-12 Physical Component Summary score to evaluate physical function profiles during receipt of chemotherapy.38 Lower Physical Component Summary scores at enrollment were associated with older age, greater comorbidity, and morning fatigue, among others. However, this study only included 81 participants with lung cancer receiving chemotherapy. A larger study (N > 300) included 30 participants with lung cancer and described functional decline for all cancer types as any decrease in activities of daily living score after one cycle of chemotherapy, of which 31.8% had functional impairment at baseline.4

This study did not find a significant association between older age and functional disability. However, as the geriatric oncology population grows exponentially,40,41 assessing disability and risk factors can identify patients in need of interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality. Currently, clinicians have limited research findings to inform adults about their risk of experiencing worsening disability from lung cancer treatments, especially new treatments such as targeted therapies (oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors), immune checkpoint inhibitors, or combinations of chemotherapy plus immune checkpoint inhibitors. This study is a start in closing these knowledge gaps for patients of all ages.

Currently, interventions to prevent disability are not regularly implemented into routine cancer care for patients with stage IV NSCLC, although their life expectancy is now improving because of newer, precision medicine–directed treatments. Interventions that improve function may also improve depression, anxiety, and cancer-specific stress. Importantly, psychologic symptoms are modifiable risk factors for which interventions exist, which could improve resiliency and prevent functional decline for patients with cancer.42 Depression is the world's leading cause of disability, yet depression, anxiety, and stress are often under-recognized and undertreated in lung cancer.43 Psychologic symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and cancer-related stress are treatable risk factors, even if cancer treatment is ineffective or even discontinued. Interventions to improve the psychologic health of older adults with advanced lung cancer are urgently needed. There are few intervention studies available, but one pilot study is currently using progressive muscle relaxation and physical therapy to address disability and resiliency outcomes (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04229381). Future studies should address the temporal relationship between psychologic symptoms and disability, functional status changes over time, and interventions to prevent functional decline.

The context of the research is considered. Strengths include that this study is one of the largest to include both functional and psychologic variables, a diverse group of participants in rural and urban areas, a larger proportion of patients with poorer ECOG PS, the newest treatments for lung cancer, and notation of location of metastases. Limitations include the correlational design and the lack of objective measurement of physical capability and cognition. Because this was a cross-sectional study, it was not possible to establish a temporal relationship between psychologic symptoms and disability. This will be the focus of subsequent longitudinal studies. Although our sample is representative of the greater Ohio population in terms of socioeconomic status and rural status, participants were drawn from an academic medical center and hence, our results may not be generalizable to patients treated in nonacademic settings. The sample also lacks substantial numbers of patients age 80 years or above, and this may have contributed to the null findings in the age group contrasts.

In conclusion, approximately one third of adults with stage IV NSCLC were found to have moderate to severe disability in usual activities and mobility activities at the time of diagnosis within 4 weeks of treatment initiation. Psychologic symptoms were significantly associated with moderate to severe disability. This relationship between psychologic symptoms and baseline disability enables the identification of at-risk patients, a process that could potentially improve resiliency and reduce rates of functional decline. Future research will explore how disability changes over time and will pilot interventions to foster resiliency and prevent functional decline.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the patients for their participation.

Carolyn J. Presley

Consulting or Advisory Role: PotentiaMetrics, Onc Live

David P. Carbone

Employment: James Cancer Center

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Nexus Pharmaceuticals Inc

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Helsinn Therapeutics, Abbvie, Inivata, Loxo, Incyte, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, EMD Serono, GlaxoSmithKline, Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Takeda

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb

Melisa L. Wong

Employment: Roche/Genentech

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Roche/Genentech

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by a Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center Pelotonia Grant (P.G.S., PI), the National Institute on Aging (C.J.P.: R03AG064374; M.L.W., K76AG064431, P30AG044281), The Ohio State University K12 Training Grant for Clinical Faculty Investigators (C.J.P.: K12CA133250), and the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale School of Medicine (P30AG021342) from the National Institute on Aging.

N.A.A. and S.J. contributed equally to this work as second authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Carolyn J. Presley, Nicole A. Arrato, Peter G. Shields, David P. Carbone, Heather G. Allore, Barbara L. Andersen

Financial support: Carolyn J. Presley

Administrative support: Peter G. Shields

Provision of study materials or patients: Carolyn J. Presley

Collection and assembly of data: Carolyn J. Presley, Sarah Janse

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Functional Disability Among Older Versus Younger Adults With Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by the authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Carolyn J. Presley

Consulting or Advisory Role: PotentiaMetrics, Onc Live

David P. Carbone

Employment: James Cancer Center

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Nexus Pharmaceuticals Inc

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Helsinn Therapeutics, Abbvie, Inivata, Loxo, Incyte, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, EMD Serono, GlaxoSmithKline, Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Takeda

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb

Melisa L. Wong

Employment: Roche/Genentech

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Roche/Genentech

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Presley C, Maggiore R, Gajra A: Lung cancer, in Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Studenski S, et al. (eds): Hazzard's Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology (ed 7). New York, NY, McGraw-Hill Education, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66:7-30, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, et al. : Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med 346:1061-1066, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoppe S, Rainfray M, Fonck M, et al. : Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 31:3877-3882, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loh KP, Lam V, Webber K, et al. : Characteristics associated with functional changes during systemic cancer treatments: A systemic review focused on older adults. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2021. https://jnccn.org/view/journals/jnccn/aop/article-10.6004-jnccn.2020.7684/article-10.6004-jnccn.2020.7684.xml [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. : Cancer statistics, 2021. CA: A Cancer J Clinicians 71:7-33, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aggarwal C, et al. : NCCN guidelines insights: Non-small cell lung cancer, version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17:1464-1472, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Presley CJ, Canavan M, Wang SY, et al. : Severe functional limitation due to pain & emotional distress and subsequent receipt of prescription medications among older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 11:960-968, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bubis LD, Davis L, Mahar A, et al. : Symptom burden in the first year after cancer diagnosis: An analysis of patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Oncol 36:1103-1111, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Presley CJ, Han L, Leo-Summers L, et al. : Functional trajectories before and after a new cancer diagnosis among community-dwelling older adults. J Geriatr Oncol 10:60-67, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung B, Laskin J, Wu J, et al. : Assessing the psychosocial needs of newly diagnosed patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer: Identifying factors associated with distress. Psychooncology 28:815-821, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cataldo JK, Brodsky JL: Lung cancer stigma, anxiety, depression, and symptom severity. Oncology 85:33-40, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahedah KK, How SH, Jamalludin AR, et al. : Depressive symptoms in newly diagnosed lung carcinoma: Prevalence and associated risk factors. Tuberculosis Respir Dis (Seoul) 82:217-226, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan DR, Forsberg CW, Ganzini L, et al. : Longitudinal changes in depression symptoms and survival among patients with lung cancer: A national cohort assessment. J Clin Oncol 34:3984-3991, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: The PHQ-9—Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16:606-613, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. : A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166:1092-1097, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horowitz MJ, Wilner NR, Alvarez WM: Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective distress. Psychosom Med 41:209-218, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss DS, Marmar CR: The Impact of events scale-revised, in Wilson JP, Keane TM. (eds): Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. New York, NY, Guilford Press, 1997, pp 399-411 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. : Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 20:1727-1736, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. : A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373-383, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundararajan V, Henderson T, Perry C, et al. : New ICD-10 version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index predicted in-hospital mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 57:1288-1294, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sage R, Ward B, Myers A, et al. : Transitory and enduring disability among urban and rural people. J Rural Health 35:460-470, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Department of Agriculture : Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. US Department of Agriculture, 2013. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. : The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in International Clinical Trials in Oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:365-376, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan I, Morris S, Pashayan N, et al. : Comparing the mapping between EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-3L and the EORTC-QLQ-C30 in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 14:60, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gill TM: Disentangling the disabling process: Insights from the precipitating events project. Gerontologist 54:533-549, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, et al. : Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol 32:1605-1619, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. : Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 5:649-656, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson RJ, Ryerson AB, Singh SD, et al. : Cancer incidence in Appalachia, 2004-2011. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 25:250-258, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitzman PH, Sutton KM, Wolf M, et al. : The prevalence of multiple comorbidities in stroke survivors in rural Appalachia and the clinical care implications. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 28:104358, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coker AL, Luu HT, Bush HM: Disparities in women's cancer-related quality of life by Southern Appalachian residence. Qual Life Res 27:1347-1356, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y: Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B 57:289-300, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Presley CJ, Han L, Leo-Summers L, et al. : Functional trajectories before and after a new cancer diagnosis among community-dwelling older adults. J Geriatr Oncol 10:60-67, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang H-J, Kim S-Y, Bae K-Y, et al. : Comorbidity of depression with physical disorders: Research and clinical implications. Chonnam Med J 51:8-18, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vodermaier A, Lucas S, Linden W, et al. : Anxiety after diagnosis predicts lung cancer–specific and overall survival in patients with stage III non–small cell lung cancer: A population-based cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage 53:1057-1065, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langford DJ, Cooper B, Paul S, et al. : Distinct stress profiles among oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage 59:646-657, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kokkonen K, Saarto T, Mäkinen T, et al. : The functional capacity and quality of life of women with advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer 24:128-136, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miaskowski C, Wong ML, Cooper BA, et al. : Distinct physical function profiles in older adults receiving cancer chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage 54:263-272, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA: Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontologist 5:165-173, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH: Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 25:1029-1036, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wildiers H, Le Saux O: Research methods: Clinical trials in geriatric oncology. Geriatr Oncol:1063-1076, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johns SA, Brown LF, Beck-Coon K, et al. : Randomized controlled pilot study of mindfulness-based stress reduction for persistently fatigued cancer survivors. Psychooncology 24:885-893, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friedrich MJ: Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA 317:1517, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]