Abstract

Background

The 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care recommend that comatose patients with return of spontaneous circulation after cardiac arrest have targeted temperature management (TTM). However, the duration of TTM remains to be elucidated.

Methods and Results

We conducted a cluster randomized trial in 10 hospitals to compare 12–24 vs. 36 h of cooling in patients with cardiac arrest who received TTM. The primary outcome was the incidence, within 1 month, of complications including bleeding requiring transfusion, infection, arrhythmias, decreasing blood pressure, shivering, convulsions, and major adverse cardiovascular events. Secondary outcomes were mortality and favorable neurological outcome (Cerebral Performance Categories 1–2) at 3 months. Random-effects models with clustered effects were used to calculate risk ratios (RR). Data of 185 patients were analyzed (12- to 24-h group, n=100 in 5 hospitals; 36-h group, n=85 in 5 hospitals). The incidence of complications within 1 month did not differ between the 2 groups (40% vs. 34%; RR 1.04, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.67–1.61, P=0.860). Favorable neurological outcomes at 3 months were comparable between the 2 groups (64% vs. 62%; RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.72–1.14, P=0.387).

Conclusions

TTM at 34℃ for 12–24 h did not significantly reduce the incidence of complications. This study did not show superiority of TTM at 34℃ for 12–24 h for neurologic outcomes.

Key Words: Cluster randomized trial, Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, Targeted temperature management

Targeted temperature management (TTM) at 32–36℃ is a strategy of reducing the core body temperature of survivors of sudden cardiac arrest to minimize neurological damage caused by severe hypoxia.1 Initial clinical trials examining this technique demonstrated significant improvement in neurological function among survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) with an initial shockable rhythm.2 However, several questions remain regarding the optimal target temperature, duration of cooling, and utility of TTM in OHCA patients with non-shockable rhythms.

A recent randomized clinical trial of 355 adults with OHCA found no significant difference in the prevalence of favorable neurological outcomes at 6 months for patients treated with TTM at 33℃ for 48 h compared with 24 h (69% vs. 64%, respectively).3 Although that study may have had limited power to detect clinically important differences, prolonged TTM at 33℃ did not result in better neurological outcomes. Similarly, an analysis of unpublished data from Japan showed no significant difference in the proportion of patients with a survival and favorable neurological prognosis when patients were divided into 2 groups according to a cut-off value of 28 h at 34℃.4 Because the group with <28 h of TTM in that registry had significantly fewer complications such as lethal arrhythmia, pneumonia, or bleeding,4 we designed the present cluster randomized study to compare the safety of hypothermia treatment at 34℃ for patients with OHCA for 12–24 vs. 36 h of cooling.

Methods

Design and Setting

We conducted a cluster randomized trial to evaluate the appropriate cooling duration (12–24 vs. 36 h) as part of TTM after resuscitation for cardiac arrest (Japanese Population-based Utstein-style with defibrillation and basic/advanced Life Support Education and implementation-Hypothermia in Duration of Cooling (J-PULSE-Hypo-DC) trial). An overview of this study has been registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (ID: UMIN000007615).

All facilities that were national or local government-designated tertiary emergency medical centers, advanced cardiovascular centers, or emergency departments of university hospitals taking part in the J-PULSE-Hypo trial in Japan were eligible to take part in this study. Ten facilities took part in this study with the approval of the ethics committee at each hospital. These facilities were assigned to either the 12- to 24-h TTM group (n=5 hospitals) or the 36-h TTM group (n=5 hospitals; Supplementary Figure). All facilities in both groups had similar capabilities to perform an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), urgent coronary angiography (CAG), primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO). There was no difference in the total number of OHCA treatments before the study and in the cooling method during TTM between the 2 groups.

The present study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for epidemiological studies and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center (M22-87-2). In addition, the relevant review boards in all 10 participating centers approved the study protocol. In participating hospitals, information concerning study objectives, methods, data management, and the right to refuse registration was disclosed to individual presenting patients. Informed consent before the introduction of TTM was waived because of the life-threatening situation. Information was delivered to the next of kin, and consent was obtained during or after the introduction of TTM in the usual manner at each hospital. The study procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study Patients

Between March 31, 2012 and December 31, 2014, consecutive patients with successful return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) after OHCA who received TTM in the 10 participating facilities were enrolled in the present study if they met the following criteria: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) stable hemodynamics after ROSC (including stabilization by drugs or assisted circulation, such as IABP or VA-ECMO); (3) remaining in a comatose state (Glasgow Coma Scale <8 points) after ROSC; and (4) presumed cardiac etiology of cardiac arrest according to the Utstein style guidelines.5 The exclusion criteria were pregnancy, acute aortic dissection, pulmonary thromboembolism, drug poisoning, and poor daily activity before onset.

Randomization

Prior to study enrollment, eligible sites were randomly assigned 1 : 1 to the 12- to 24-h group or the 36-h group (Figure). The allocation process was conducted by a statistician in clinical research center. Allocation was based on a random number allocation table generated using SAS. Allocation was done using a block randomization method stratified by the estimated number of cardiogenic cardiac arrests patient per year at the institution. It was not possible to mask the allocation of each facility. However, the status of facilities other than one’s own and the allocation status overall were not disclosed to the principal investigators during the study period.

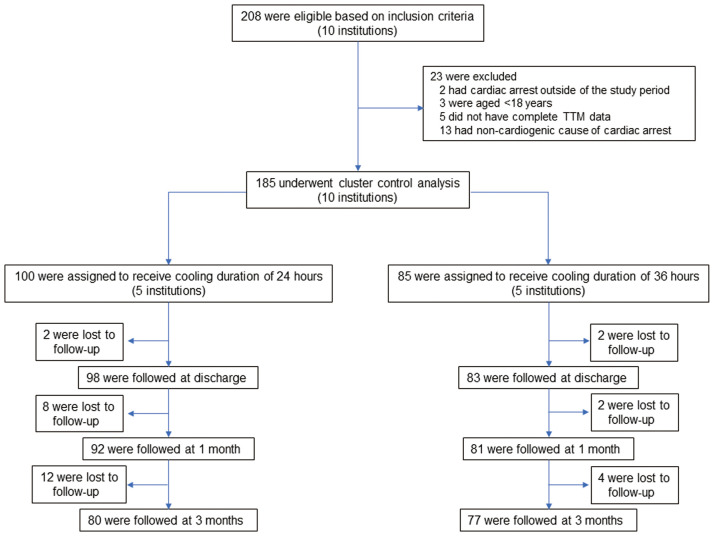

Figure.

Flow chart of study patients. TTM, targeted temperature management.

TTM Protocol

According to the TTM protocol, after sedation with analgesia, ice-cold intravenous fluid was administered over 30–60 min to initiate therapeutic hypothermia. If the patient was hemodynamically unstable, hypothermia management with catecholamines and assisted circulation devices was initiated. CAG was performed when deemed necessary. Initiation or maintenance of therapeutic hypothermia was attempted by 1 of the following 2 methods with 3 devices: (1) surface cooling with a cooling device and self-adhesive, hydrogel-coated pads (Arctic Sun 2000; Medivance, Louisville, KY, USA); (2) blood cooling using an endovascular cooling device (CoolGard 3000; Alsius, Irvine, CA, USA); and (3) VA-ECMO with a heat exchanger unit (Heater-cooler system, MSH-15; Senko, Tokyo, Japan). Mild hypothermia (34℃) was maintained for 12–24 or 36 h based on group assignment. Rewarming was conducted slowly and gradually and took at least 24 h. The TTM protocol was determined by each institution individually.

Data Collection

All event times were measured by the dispatch center clock, and times of collapse and first bystander resuscitation attempts were obtained from bystanders. Cardiac arrest was defined as the cessation of cardiac mechanical activity, manifesting as unresponsiveness, apnea (or gasping breathing), and the absence of a pulse. The arrest was presumed to be from a cardiac cause unless it was known to have been caused by a non-cardiac cause, including trauma, drowning, and asphyxia. Resuscitation attempts were documented by both paramedics and the attending physicians according to Utstein Style reporting guidelines.5

First documented pulseless rhythm was defined as the first electrocardiogram rhythm documented at the time the patient became pulseless and, for those patients with unwitnessed or unmonitored arrests, it represents the first rhythm documented at the time a monitor arrives and is applied. Index events are defined as the patient’s first cardiac arrest event during this hospitalization. In the present study, the categories of acute respiratory compromise leading to cardiopulmonary arrest and cardiopulmonary arrest were combined into a single category that comprises ‘cardiac arrest’. The timing of cooling induction, the cooling method, the target body temperature, the speed of rewarming, the management of adverse events, and the use of sedatives and muscle relaxants in TTM were according to the standards used during routine clinical practice at the participating facilities.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of complications within 1 month. Complications included infection, bleeding requiring transfusion, arrhythmia (new-onset premature ventricular contraction, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia [NSVT], sustained ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation [VF]/pulseless VT, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, sick sinus syndrome, or atrioventricular block), decreasing blood pressure, shivering, convulsions and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE; cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, or non-fatal pulmonary embolism) evaluated by an independent committee under masked allocated groups.

Secondary outcomes were mortality and favorable neurological outcome (Cerebral Performance Categories [CPC]) at 24 h, 7 days, and 1 and 3 months. The favorable neurological outcome was defined according to the Glasgow-Pittsburgh CPC of 1 (good performance) or 2 (moderate disability) on a 5-category scale.5

Data Safety and Monitoring Board

This study set and held the Data Safety and Monitoring Board. This Board evaluated the primary endpoint of complications during the study in the setting, where group assignment was not disclosed.

Sample Size

Sample size calculations were performed on the basis of results from a previous study.6 We assumed that the incidence of complications in the 12- to 24- and 36-h groups would be 36% and 56%, respectively. Based on additional assumptions of an interclass correlation of 0.1, a power of 0.9, and a 2-sided P value of 0.01, a total of 232 patients would be needed. If the dropout rate was set at 20%, then 280 patients would be needed.7

Statistical Analyses

The baseline characteristics for the 2 groups were summarized using descriptive statistics. The significance of differences between groups were evaluated using the Chi-squared test for binary and categorical data and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-parametric data. The primary analyses followed the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle and compared the proportion of primary and secondary outcomes between the intervention and control groups. In the analysis, we used random (mixed) effects models under the missing-at-random assumption to the ITT population. We included variation of the allocated clusters in the model in order to allow for the possibility that outcome measures from individuals within the allocated cluster may not be independent in the analysis of the cluster randomized trial.7 The method was used to estimate risk ratio (RR) as a measure of the effect and to calculate the associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Multivariable analyses were performed to adjust for the possible effects of an imbalance in baseline variables. We also analyzed the data using the inverse probability of censoring weighted method for missing data. The censoring probability was calculated by a logistic model with baseline variables (age, sex, witness, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation CPR, and VF/pulseless VT).8 All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Enrollment and Patient Characteristics

In all, 208 consecutive patients with OHCA were initially screened and 185 patients were ultimately enrolled in the study (Figure). Although the planned sample size was 280, the study was stopped after the enrollment of 185 patients due to study budget reasons.

The clinical characteristics of the study patients are presented in Table 1. The median age of the study patients overall was 60 years (interquartile range [IQR] 52–70 years), 149 patients (81%) were male, 120 patients (65%) showed an initial shockable rhythm, and 115 patients (62%) had ROSC before admission. Among the study patients, surface cooling was used in 130 patients (70%) and an endovascular cooling device was used in 55 patients (30%). There were no significant differences in baseline clinical characteristics between the 12- to 24- and 36-h groups except for age (median [IQR] 67 [57–75] vs. 59 [47–68] years, respectively; P<0.001), the rate of bystander-initiated CPR (55% vs. 61%, respectively; P=0.019), and the time from collapse to ROSC (17 [12–25] vs. 20 [16–27] minutes, respectively; P=0.047).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Targeted Temperature Management for 12–24 or 36 h

| 12- to 24-h group (n=100) |

36-h group (n=85) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. assigned hospital | 5 | 5 | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 67 [57–75] | 59 [47–68] | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 76 (76) | 73 (86) | 0.091 |

| Arrest witnessed | |||

| Bystander | 86 (86) | 69 (81) | 0.375 |

| Resuscitation factors | |||

| Bystander-initiated CPR | 55 (55) | 61 (72) | 0.019 |

| Bystander AED use | 23 (23) | 17 (17) | 0.621 |

| Shockable rhythm on EMT arrival | 66 (66) | 54 (64) | 0.726 |

| Clinical status at hospital arrival | |||

| ROSC before admission | 62 (62) | 53 (62) | 0.981 |

| Time from collapse to ROSC (min) | 17 [12–25] | 20 [16–27] | 0.047 |

| Time from collapse to hospital arrival (min) | 33 [26–47] | 31 [25–38] | 0.189 |

| Primary disease | –A | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 51 (51) | 33 (39) | |

| Brugada syndrome | 4 (4) | 3 (4) | |

| Vasospastic angina pectoris | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | |

| Long QT syndrome | 9 (9) | 14 (16) | |

| Other | 13 (13) | 28 (33) | |

| Missing data | 23 (23) | 3 (4) | |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are presented as the median [interquartile range] or n (%). ABecause there was a significant difference in the amount of missing data between the 2 groups, a P value has not been listed. AED, automated external defibrillator; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EMT, emergency medical technician; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Table 2 shows the TTM status and subsequent treatment. The median (IQR) duration of target temperature was 24 h (14–24 h) in the 12- to 24-h group and 36 h (IQR 36–41 h) in the 36-h group. There were no significant differences in time to intervention and TTM methods between the 2 groups. There were also no significant differences in subsequent treatment between the 12- to 24- and 36-h groups except for ECPR (35% vs. 16%, respectively; P=0.016).

Table 2.

Targeted Temperature Management Status and Subsequent Treatment Among Patients Undergoing Targeted Temperature Management for 12–24 or 36 h

| 12- to 24-h group (n=100) |

36-h group (n=85) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration at target temperature (min) | 24 [14–24] | 36 [36–41] | <0.001 |

| Time to intervention (min) | |||

| Time from collapse to start of TTM | 56 [36–95] | 60 [42–125] | 0.207 |

| Time from ROSC to start of TTM | 27 [18–55] | 37 [20–64] | 0.205 |

| Time from start of TTM to achievement of target temperature |

199 [60–390] | 154 [100–210] | 0.338 |

| TTM methods used | 0.229 | ||

| Body surface | 74 (74) | 56 (66) | |

| Intravascular | 26 (26) | 29 (34) | |

| Subsequent treatment | |||

| CAG | 89 (89) | 75 (89) | 0.870 |

| PCI | 51 (51) | 33 (39) | 0.097 |

| IABP | 44 (45) | 39 (46) | 0.894 |

| VA-ECMO | 34 (35) | 16 (19) | 0.016 |

| Rewarming duration (h) | 9.5 [5.8–14] | 12.0 [8.0–22.0] | 0.023 |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are presented as the median [interquartile range] or n (%).CAG, coronary angiography; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pumping; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; TTM, targeted temperature management; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Primary Outcome: Incidence of Complications Within 1 Month

The follow-up rate was 94% (n=173) at 1 month and 85% (n=157) at 3 months (Figure). Complications within 1 month occurred in 40 patients (40%) in the 12- to 24-h group and in 29 patients (34%) in the 36-h group. The primary outcome did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (adjusted RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.67–1.61, P=0.86; Table 3).

Table 3.

Primary Outcome After Targeted Temperature Management in Patients Undergoing Targeted Temperature Management for 12–24 or 36 h

| No. patients (%) | Crude | AdjustedA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12- to 24-h group (n=100) |

36-h group (n=85) |

RR (95% CI) |

P value | RR (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Complications within 1 month | 40 (40) | 29 (34) | 0.85 (0.58–1.25) | 0.450 | 1.04 (0.67–1.61) | 0.860 |

| Infection | 6 (6) | 14 (17) | ||||

| Bleeding requiring transfusion | 19 (19) | 15 (18) | ||||

| Arrhythmia | 10 (10) | 1 (1) | ||||

| Hypotension | 7 (7) | 1 (1) | ||||

| Shivering | 11 (11) | 2 (2) | ||||

| Convulsion | 4 (4) | 6 (7) | ||||

| MACE | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | ||||

AAdjusted for hospital as a random effect. CI, confidence interval; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, or non-fatal pulmonary embolism); RR, risk ratio.

Table 4 shows mortality and favorable neurological outcome (secondary outcomes) in the 2 groups. Mortality at 7 days and 1 and 3 months did not differ significantly after adjustment for imbalanced baseline characteristics (age and bystander CPR) and established risk factors (sex, the rate of witnessing the arrest, and the presence of VF/pulseless VT). Regarding favorable neurological outcomes, there was a significant difference in good functional outcomes (CPC 1–2) at 7 days (RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.04–1.68, P=0.022) after adjustment for imbalanced baseline characteristics and missing data. However, there were no significant differences in favorable neurological outcomes at 1 or at 3 months between the 2 groups. Other long-term secondary outcomes at 1 and 3 months did not differ between the 2 groups.

Table 4.

Secondary Outcomes After Targeted Temperature Management for 12–24 or 36 h

| No. patients (%) | Crude | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12- to 24-h group (n=100) |

36-h group (n=85) |

RR (95% CI) |

P value | RR (95% CI) |

P value | RR (95% CI) |

P value | RR (95% CI) |

P value | |

| Mortality | ||||||||||

| 24 h | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 0.59 (0.11–3.13) | 0.689 | 0.53 (0.39–0.72) | <0.001 | NA | NA | ||

| 7 days | 14 (14; n=99) | 6 (7) | 0.49 (0.20–1.24) | 0.156 | 0.76 (0.62–0.93) | 0.007 | 0.84 (0.66–1.08) | 0.178 | 0.84 (0.66–1.08) | 0.167 |

| 1 month | 18 (20; n=92) | 14 (17; n=81) | 0.88 (0.47–1.66) | 0.845 | 0.91 (0.62–1.32) | 0.612 | 1.06 (0.66–1.69) | 0.823 | 1.08 (0.67–1.74) | 0.755 |

| 3 months | 21 (26; n=80) | 15 (19; n=77) | 0.74 (0.41–1.33) | 0.347 | 0.74 (0.44–1.26) | 0.300 | 0.93 (0.50–1.76) | 0.830 | 0.94 (0.50–1.75) | 0.835 |

| Favorable neurological outcome (CPC 1–2) | ||||||||||

| 7 days | 53 (58; n=92) | 44 (52; n=84) | 1.10 (0.84–1.44) | 0.545 | 1.11 (0.82–1.51) | 0.495 | 1.33 (1.03–1.70) | 0.027 | 1.34 (1.04–1.73) | 0.022 |

| 1 month | 56 (62; n=90) | 48 (59; n=81) | 1.05 (0.82–1.34) | 0.755 | 1.02 (0.75–1.37) | 0.916 | 1.17 (0.82–1.68) | 0.389 | 1.19 (0.83–1.68) | 0.344 |

| 3 months | 51 (64; n=80) | 48 (62; n=77) | 1.02 (0.82–1.30) | 0.870 | 0.91 (0.72–1.14) | 0.387 | 1.16 (0.87–1.53) | 0.311 | 1.15 (0.87–1.53) | 0.315 |

Model 1 was adjusted for hospital (random effect); Model 2 was further adjusted for age, sex, witness, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and ventricular fibrillation (VF)/pulseless ventricular tachycardia; and Model 3 was adjusted for all factors in Model 2 using inverse probability censoring for missing data. CI, confidence interval; CPC, Cerebral Performance Category; NA, not applicable; RR, risk ratio.

Discussion

This study is the first cluster randomized controlled trial in Japan to evaluate the appropriate duration of cooling in patients with ROSC after OHCA. The major findings of this study are that: (1) there was no significant difference in complications associated with cooling duration and no differences in outcomes between the 12- to 24-h and the 36-h cooling groups; and (2) favorable neurological outcomes at 3 months were also comparable between the 2 groups.

The ideal duration of TTM, as well as the ideal technique to provide TTM, remain to be elucidated. Current resuscitation guidelines give a weak recommendation for TTM at 32–36℃ for at least 24 h.9 This recommendation is based on protocols of pioneer studies,10,11 and lacks sufficient supporting evidence. In neonates with hypoxic–ischemic brain injury, TTM at 33℃ for 72 h is standard practice,12,13 and prolonged cooling for 120 h in 1 trial resulted in significant harm.12 In 2017, Kirkegaard et al3 conducted a randomized multicenter study, recruiting 355 patients from 6 European countries and comparing a standard cooling duration of 24 h with a prolonged cooling duration of 48 h. In that study, there was no significant difference in the primary outcome, with favorable neurological outcomes at 6 months (64% vs. 69% in the 24- and 48-h duration groups, respectively; RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.93–1.25, P=0.33).3 Conversely, significantly more patients had hypotension in the 48- than 24-h group (62% vs. 49%, respectively; P=0.013). Therapeutic hypothermia is also expected to cause bleeding by altering the functionality of clotting enzymes, decreasing fibrinogen levels, and inhibiting platelet function.14–16 The question remains whether hypothermia consequently increases the risk of bleeding or hypotension. In the present study, among patients who received TTM at 34℃, the incidence of both bleeding requiring transfusion and decreases in blood pressure were comparable between the 24- and 36-h cooling groups. Rates of other adverse events, such as arrhythmia, shivering, convulsion, or MACCE, were also comparable between the 2 groups (Table 2). Long-term thermoregulatory therapy can now be performed more safely with the advent of thermoregulatory systems with automatic thermoregulation, and thus future protocols for thermoregulatory therapy should be subdivided.

In the present study, favorable neurological outcomes at 3 months were also comparable between the 2 groups. This result supports those reported by Kirkegaard et al.3 However, the prevalence of patients with favorable neurological outcomes was lower in the present study compared with the study of Kirkegaard et al.3 These differences may be derived from the lower prevalence of bystander CPR, lower shockable rhythm (and longer time from collapse to ROSC) in the present study than in the study of Kirkegaard et al.3 In particular, regarding initial cardiac arrest rhythm, the present study included 35% patients with non-shockable rhythm, whereas Kirkegaard et al3 included 11% patients with non-shockable rhythm. Recently, the multicenter HYPERION trial, a randomized controlled trial including 584 patients with cardiac arrest in a non-shockable rhythm due to any cause, showed that moderate therapeutic hypothermia at 33℃ for 24 h led to a higher percentage of patients who survived with a favorable neurological outcome at Day 90.17 In the present study the target temperature was set at 34℃ because the study protocol was written prior to the publication of the TTM. If we had set the target temperature lower than 34℃, the prevalence of favorable neurological outcomes may have increased.

The duration of TTM in the prolonged-cooling group was set to 36 h. There is no scientific evidence that specifically supports 36–48 h or other durations longer than 24 h. The 36-h period was selected as the median value of cooling duration based on a previous observational study managed by our study group,6 and to balance a clear augmentation of “cooling dose” against an expected prolonged intensive care unit stay and the risk of more adverse events.

Study Limitations

Although the present study was a cluster randomized study, patient enrollment was stopped after 185 patients due to budgetary reasons. Because the statistical power of the study was insufficient to detect a difference in the incidence of complications, further research is warranted. In addition, there were significant differences in age, bystander-initiated CPR, and time from collapse to ROSC between the 2 groups. Because this study had only 5 clusters per arm owing to practical issues with recruiting participants and the number of study patients was low, there may have been an imbalance among the groups; our study may have had residual confounding due to cluster effects.

Unlike studies in Europe and the US, the present study included patients whose event was not witnessed. Therefore, there may have been some patients who had delayed initiation of TTM. It is necessary to study the effect of temperature control therapy on cardiac arrest patients with a similar severity of primary brain damage at the time of ROSC. However, the issue is that currently there is no standard evaluation method for primary brain damage after ROSC.

Conclusions

Differences in the duration of cooling were not associated with clear benefits in patients with cardiac arrest who received therapeutic hypothermia after resuscitation. However, this study may have had limited power to detect clinically important differences, and further research is warranted.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by research grants for cardiovascular disease (H22-Shinkin-02) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

Disclosures

S.Y. is a member of Circulation Reports’ Editorial Team. None of the authors have any financial interests to disclose and any further conflicts of interest to declare.

IRB Information

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Japan (M22-87-2). This trial is registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (ID: UMIN000007615).

Supplementary Files

Supplementary Figure

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the members of the J-PULSE-Hypo-DC Trial Study Group who participated in this multicenter observational study. The study was conducted at the following sites: Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Osaka; Department of Cardiovascular Medicine/Emergency and Critical Care Center, Dokkyo Medical University Hospital, Tochigi; Advanced Critical Care and Emergency Center, Sapporo Medical University Hospital, Sapporo; Cardiovascular Division, Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka; Advanced Critical Care and Emergency Center, Yokohama City University Medical Center, Yokohama; Emergency and Critical Care Medicine Center, Osaka City General Hospital, Osaka; Department of Emergency Medicine, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Kobe; Advanced Medical Emergency and Critical Care Center, Yamaguchi University Hospital, Ube; Department of Cardiology, Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizens Hospital, Hiroshima; and Emergency Medical Center, Kagawa University Hospital, Kagawa, Japan.

Data Availability

The deidentified participant data will not be shared.

References

- 1. Berg KM, Soar J, Andersen LW, Bottiger BW, Cacciola S, Callaway CW, et al.. 2020 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation 2020; 142: S92–S139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group.. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kirkegaard H, Søreide E, de Haas I, Pettilä V, Taccone FS, Arus U, et al.. Targeted temperature management for 48 vs 24 hours and neurologic outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 318: 341–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kagawa E, Dote K, Kato M, Sasaki S, Oda N, Nakano Y, et al.. Do lower target temperatures or prolonged cooling provide improved outcomes for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest treated with hypothermia? J Am Heart Assoc 2015; 4: e002123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cummins RO, Chamberlain DA, Abramson NS, Allen M, Baskett PJ, Becker L, et al.. Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: The Utstein Style. A statement for health professionals from a task force of the American Heart Association, the European Resuscitation Council, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Australian Resuscitation Council. Circulation 1991; 84: 960–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kagawa E, Ishihara M, Maruhashi T, Yonemoto N, Yokoyama H, Nagao K, et al.. Abstract P200: Impact of duration of cooling in mild therapeutic hypothermia on comatose survivors of cardiac arrest Circulation 2009; 120: S1484–S1485. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hayes RJ, Moulton L.. Cluster randomized trials. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2009.

- 8. Seaman SR, White IR.. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res 2013; 22: 278–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabanas JG, Donnino MW, Drennan IR, Hirsch KG, et al.. Adult basic and advanced life support: 2020 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2020; 142: S366–S468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, Jones BM, Silvester W, Gutteridge G, et al.. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group.. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Pappas A, McDonald SA, Das A, Tyson JE, et al.. Effect of depth and duration of cooling on deaths in the NICU among neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 312: 2629–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Azzopardi D, Strohm B, Marlow N, Brocklehurst P, Deierl A, Eddama O, et al.. Effects of hypothermia for perinatal asphyxia on childhood outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gong P, Zhang MY, Zhao H, Tang ZR, Hua R, Mei X, et al.. Effect of mild hypothermia on the coagulation-fibrinolysis system and physiological anticoagulants after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a porcine model. PLoS One 2013; 8: e67476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mitrophanov AY, Rosendaal FR, Reifman J.. Computational analysis of the effects of reduced temperature on thrombin generation: The contributions of hypothermia to coagulopathy. Anesth Analg 2013; 117: 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Awad A, Taccone FS, Jonsson M, Forsberg S, Hollenberg J, Truhlar A, et al.. Time to intra-arrest therapeutic hypothermia in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients and its association with neurologic outcome: A propensity matched sub-analysis of the PRINCESS trial. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 1361–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lascarrou JB, Merdji H, Le Gouge A, Colin G, Grillet G, Girardie P, et al.. Targeted temperature management for cardiac arrest with nonshockable rhythm. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 2327–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure

Data Availability Statement

The deidentified participant data will not be shared.