Abstract

Taste sensation is the gatekeeper for direct decisions on feeding behavior and evaluating the quality of food. Nutritious and beneficial substances such as sugars and amino acids are represented by sweet and umami tastes, respectively, whereas noxious substances and toxins by bitter or sour tastes. Essential electrolytes including Na+ and other ions are recognized by the salty taste. Gustatory information is initially generated by taste buds in the oral cavity, projected into the central nervous system, and finally processed to provide input signals for food recognition, regulation of metabolism and physiology, and higher-order brain functions such as learning and memory, emotion, and reward. Therefore, understanding the peripheral taste system is fundamental for the development of technologies to regulate the endocrine system and improve whole-body metabolism. In this review article, we introduce previous widely-accepted views on the physiology and genetics of peripheral taste cells and primary gustatory neurons, and discuss key findings from the past decade that have raised novel questions or solved previously raised questions.

Keywords: Taste, Taste buds, Geniculate ganglion, Synaptic transmission, Signal transduction, Hormones

INTRODUCTION

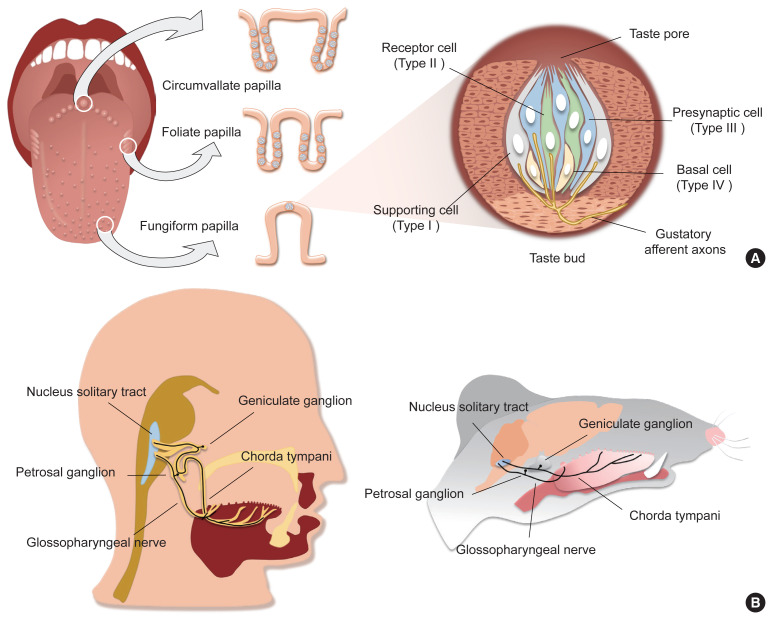

Taste is one of the specialized chemical senses that detects exogenous chemicals, and arises from contact of non-volatile chemicals dissolved in the saliva and mucus in the oral cavity with taste buds, the primary taste organs. Taste buds are located on the fungiform papilla (FuP), foliate papilla (FoP), and circumvallate papilla (CVP), but not on the filiform papilla, among the four types of papillary structures on the surface of the tongue (Fig. 1A). In addition, they are abundantly embedded in the soft palatal mucosa as well as the pharynx, and to a lesser extent the larynx, the epiglottis, and the bronchus. FuP-located taste buds are innervated by the chorda tympani nerve, a branch of the facial nerve, whereas FoP- and CVP-located taste buds are innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve. The chorda tympani and glossopharyngeal nerve, whose neuronal cell bodies are located at the geniculate and petrosal ganglion, respectively, project their axons to the nucleus solitary tract, relaying taste information into the central nervous system (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

The peripheral gustatory system in humans and mice. (A) The location of three types of papillae and the structure of the taste buds. The fungiform papilla (FuP) are distributed over the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, the foliate papilla are located on the lateral sides of the posterior tongue, and the circumvallate papilla (CVP) are mostly located on the center of the posterior one-third of the tongue. Each papilla contains one or more taste buds consisting of four types of taste cells: type I supporting (glial-like) cells, type II receptor cells, type III synaptic cells, and type IV basal (progenitor) cells. (B) The gustatory pathway from the taste buds to the brainstem in humans (left) and mice (right). Taste buds in the FuP are innervated by the chorda tympani, cranial nerve (CN) VII, and the taste buds in the FuP and CVP are innervated by the glossopharyngeal, cranial nerve IX. Taste impulses carried by CN VII and CN IX synapse in the solitary tract nucleus in the medulla oblongata of the brainstem.

A taste bud is composed of 50 to 100 epithelial cell aggregates arranged into a shape of an onion bulb, and is surrounded by lingual keratinocytes, which are morphologically distinct (Fig. 1A). Early ultrastructural analyses distinguished intragemmal—within any budlike or bulblike body—cells into four types of taste bud cells according to their morphology [1,2]. This classification is widely used today as it accurately reflects the gene expression patterns and physiological characteristics of each type of taste bud cell. Type I cells, the most abundant cell type (accounting for half of the total intragemmal cell population), have irregular and indented margins and wrap other types of cells at the periphery of taste buds. As they are reminiscent of glial cells surrounding neurons in the brain, they are referred to as “glia-like cells.” Type II cells, which show a spindle shape with a large, ovoid nucleus, are known as “receptor cells” due to their cellular responses to sweet, umami, or bitter stimuli via G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) pathways. Type III cells, which accumulate synaptic vesicles toward nearby innervating neurons, are referred to as “presynaptic cells.” At the base of taste buds, type IV cells arise from perigemmal stem/progenitor cells, and differentiate into other types of intragemmal cells.

In this review, we introduce recent advances in understanding peripheral taste decoding, including (1) the discovery of non-canonical chemical synapses in type II cells, (2) the unexpected participation of type II cells in sensing appetitive salty taste, (3) the molecular mechanism of sour taste and its limitations, and (4) the dedicated responses and molecular heterogeneity of primary gustatory neurons.

DISCOVERY OF NON-CANONICAL CHEMICAL SYNAPSES IN TYPE II CELLS

Type II cells detect either of sweet, umami, or bitter tastants via taste receptors, the subfamily of GPCR superfamily [3–6]. Expression of each type of taste receptor differs in a taste modality-specific manner. The sweet or umami taste receptor cell (TRC) only expresses T1R3, the co-receptor for sweet and umami tastes, forming a heterodimer with T1R2 or T1R1, respectively [3,4,6]. In contrast, the single bitter TRC expresses multiple bitter taste receptors (T2Rs) among the 25 and 35 T2Rs in human and mice, respectively, but T2R seems to function alone [7]. Taste receptors initiate intracellular signal transduction by stimulating gustducin (Ggust). Ggust is a taste-specific Gα protein with amino acid sequences similar to Gi [7], which simultaneously increases intracellular Ca2+ and decreases cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) [8,9]. Using an early version of chemogenetics, a receptor activated solely by a synthetic ligand (RASSL), artificial manipulation of sweet and bitter TRCs induced attractive and aversive behaviors for spiradoline, respectively [6,10]. Thus, one could infer that intracellular cAMP reduction leads to activation in type II TRCs. Since most excitable cells are hyperpolarized by intracellular cAMP reduction, this unique characteristic of type II TRCs is remarkable. However, the mechanism through which cAMP reduction leads to cellular activity remains elusive [8].

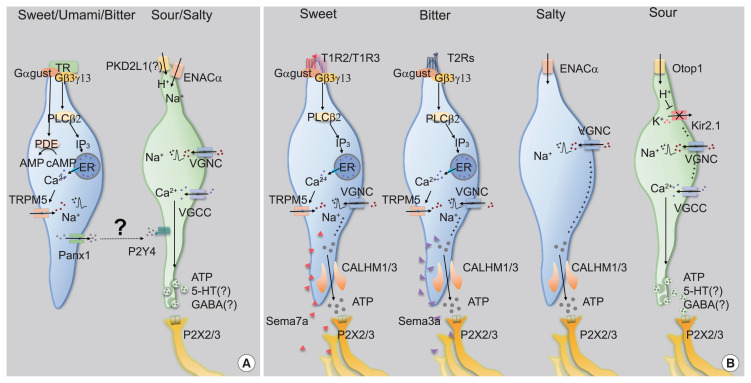

In contrast, the role of intracellular Ca2+ signaling has been well established. The Gβ3,γ13 complex, which is coupled to Ggust, dissociates from it upon taste receptor stimulation [11]. The free Gβ3,γ13 complex activates phospholipase Cβ2 (PLCβ2), hydrolyzing phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate into inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol. IP3 opens IP3R3 on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, increasing cytosolic Ca2+ levels [12]. As a Ca2+-activated Na+ channel, transient receptor potential M5 (TrpM5) induces depolarization [13,14], and finally generates action potentials in Type II TRCs (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of past and current understanding of taste transduction in type II and type III taste cells. (A) Past proposed model. Type II taste cells transmit sweet, umami, or bitter taste signals to afferent nerve fibers in a type III taste cell-dependent manner, while type III taste cells transmit either salt or sour taste signals to afferent nerve fibers. (B) Current proposed model. Type II taste cells, salt cells, and type III taste cells individually transmit taste signals of sweet or bitter, salt, and sour tastes, respectively, to the afferent nerve fibers paired with each taste cell. Type II taste cells detect sweet, umami, or bitter taste by G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) that act in pairs (T1R2+T1R3 for sweet, and T1R1+T1R3 for umami) or act alone (T2Rs for bitter). GPCR-mediated signal transduction elevates the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration by releasing Ca2+ from the intracellular stores. Elevation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ in turn activates transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily m member 5 (TRPM5), depolarizes the cell to generate action potentials through voltage-gated sodium channel (VGNC), and releases adenosine triphosphate (ATP) through calcium homeostasis modulator 1/3 (CALHM1/3). Semaphorin 7A (SEMA7A) secreted by sweet taste receptor cells (TRCs) and SEMA3A secreted by bitter TRCs guide sweet and bitter ganglion neurons to the sweet and the bitter TRCs, respectively. Sodium cells are depolarized by the influx of Na+ through amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel alpha subunit (ENACα). Action potentials are generated by an additional Na+ influx through voltage-gated sodium channel (VGNA) activation, independently of the intracellular Ca2+ signaling pathway, eventually releasing ATP through CALHM1/3. Type III taste cells detect sour taste by H+ influx through Otop1 channels. Intracellular acidification inhibits Kir2.1, and sequentially activates VGNA and voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC), leading to neurotransmitter (NT) release using synaptic vesicles. Gαgust, Gα-gustducin; PDE, phosphodiesterase; PLCβ2, phospholipase Cβ2; IP3, inositol trisphosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; Panx1, pannexin-1; PKD2L1, polycystin 2 like 1; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; P2X2, P2X purinoceptor 2; P2X3, P2X purinoceptor 3; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Otop1, otopetrin-1; Kir2.1, inward rectifier K+ channel.

There has been a consensus that type II cells function as the cellular sensors for tastants, but also a long debate regarding how sensory information is transmitted to primary gustatory neurons. The absence of intracellular synaptic structures such as synaptic vesicles in ultra-high resolution transmission electron micrography images [2,15] and synaptic molecules in immunohistochemistry [15] had been a strong evidence that type II cells transmit the sensory information they generate by releasing synaptic vesicles of type III cells via cell-cell communication systems such as gap junctions [16]. Nonetheless, this proposal presented an insufficient explanation for the crosstalk-less transmission of each sensation modality.

Among the several neurotransmitters released from taste buds [17,18], adenosine triphosphate (ATP) has been highlighted as the genuine neurotransmitter of type II cells because genetic ablation of extracellular purinergic receptor X2 (P2X2) and P2X3 simultaneously results in depleted nerve responses and behaviors to most modalities of taste stimuli [19]. This means that a specific neurotransmitter does not transmit each specific modal taste, implying the existence of a direct connection between taste cells and gustatory neurons.

The discovery of calcium homeostasis modulator 1/3 (CALHM1/3) has been the master key that solves the questions raised above. First, all type II cells express CALHM1/3 [20,21]. Second, genetic depletion of CALHM1 impairs nerve responses and preference behaviors toward sweet, bitter, and umami tastants. Finally, CALHM1/3 directly effluxes ATP upon taste stimulation [20,21]. Therefore, CALHM1/3 provides the mechanism of gustatory information transmission without synaptic vesicles, refuting the cell-cell communication model and ultimately suggesting a novel type of purinergic synapses without exocytosis (Fig. 2B).

RESPONSIBILITY OF TYPE II CELLS IN FuP FOR APPETITIVE SALTY TASTE

Usually, a low concentration of Na+ results in an appetitive salty taste, whereas a high concentration manifests as an aversive salty taste. Although the salt appetite induced by Na+ depletion makes this simple classification unclear [22], amiloride serves as a solid branching point because it blocks gustatory responses to NaCl under 100 mM, but not above 100 mM. Thus, the former is regarded as amiloride-sensitive salty taste, and the latter as amiloride-insensitive [23,24]. As amiloride is an inhibitor of epithelial sodium channel (ENAC), ENAC has been believed to mediate appetitive salty taste. An ENAC heterotrimeric complex composed of ENACα, β, and γ functions as a selective Na+ channel that passively permeates extracellular Na+ in the nephrons [25]. In CVP, ENACα is expressed in type III cells [23]. Moreover, conditional ablation of Scnn1a, an ENACα-encoding gene, in all mature taste cells resulted in diminished nerve responses and preferences for a low concentration of Na+ in an amiloride-dependent manner [23]. Therefore, ENACα has been suggested to be required for appetitive salty taste detection (Fig. 2A).

However, multiple groups have raised questions about the role played by ENAC. The generation of fluorescent tag-inserted knock-in mice for Scnn1β and Scnn1γ revealed that neither is co-expressed with ENACα in taste buds, thereby implying that appetitive salty taste perception is instead initiated by an unknown mechanism, not by the heterotrimeric ENAC complex [26]. Moreover, an independent electrophysiological approach revealed that an amiloride-sensitive current was not recorded in ENACα-expressing cells in CVP, but in FuP [27]. Surprisingly, the cells expressing ENACα in FuP were positive for CALHM1/3, the novel marker of type II cells. CALHM3 knockout (KO) mice lost amiloride-sensitive nerve responses and attractive behavior for salt, indicating that appetitive salty taste is mediated by type II cells and refuting the previous hypothesis of engagement of type III cells (Fig. 2B) [27]. However, others reported that CALHM1 KO mice, which had lost an additional component for purinergic transmission, had a normal ability to sense low concentrations of salt [28]. For the moment, more comprehensive evidence is needed to establish the paradigm of appetitive salty taste.

Cations other than Na+ are also detected as taste. One of the bitter receptors, taste 2 receptor member 7 has been reported to detect several metal ions, although in vivo evidence is still required [29,30]. Moreover, tongue slice imaging was presented to support that type II cells respond to Cl−, representing amiloride-insensitive salty taste, but this possibility requires further investigation [31].

SOUR SENSING MECHANISM OF TYPE III CELLS

A series of genetic experiments revealed that type III cells are required for sensing sour taste [32]. Polycyctic kidney disease 2-like 1 (PKD2L1), a specific molecular marker of type III cells, shows a distinctive expression pattern in double immunohistochemistry against type II cell markers [33]. PKD2L1-TeNT mice, which express tetanus toxin (TeNT) to silence synaptic transmission of type III cells, showed diminished nerve responses to sour stimuli [34]. Therefore, one might expect that type III cells promote aversive behaviors because sour stimuli evoke aversive behaviors and activate type III cells. However, it is interesting to note that the behavior of PKD2L1-TeNT mice in response to sour stimuli had not been reported until recently.

The Oka group recently reported the unexpected results that PKD2L1-TeNT mice displayed a normal level of aversive behavior against sour stimuli [35]. Rather, optogenetic activation of type III cells does not induce aversive, but attractive behaviors. Although the attractive behavior induced by optogenetics is suspected by other group, it is still agreed that artificial activation of type III cells does not induce aversion by itself [36]. This means that type III cell activity is unnecessary and insufficient to drive sour-induced aversive behaviors, despite type III cellular responses. It has subsequently been shown that trigeminal chemesthesis is additionally required to generate sour-induced aversion [37].

How do type III cells respond to acids? Initially, PKD2L1, the well-known marker of type III cells, had received attention as an acid sensor (Fig. 2A) [33], but this possibility was quickly refuted because PKD2L1 KO mice responded to acidic stimuli normally [38]. A recent transcriptomic comparison between type II and type III cells indicated that otopetrin 1 (Otop1) is the genuine sour sensor [39]. Otop1 gates protons from outside into the cytosol, mediates intracellular acidification to close Kir2.1 [40], and ultimately depolarizes type III cells (Fig. 2B) [41]. Although Otop1 KO mice lack both the electrophysiologic nerve responses and the ganglionic Ca2+ responses to sour stimuli, they still show normal acid-induced aversive behaviors, confirming that the sour taste itself is insufficient to generate aversion [37,41].

Type III cells also respond to carbonated water, pure water, and high salts [24,35,42]. The detection of both carbonated and pure water is an intrinsically identical phenomenon involving reduction of the pH of solvents. CO2 from carbonated water is dissolved into the solvent by carbonic anhydrase 4 expressed in type III cells, generating protons [42]. The ingestion of pure water removes bicarbonate from the saliva, transiently reducing pH [35]. A further investigation is required to establish the responses of type III cells to high salts [24].

Taken together, it is currently accepted that type III cells mainly respond to stimuli that change the pH or ionic balance of the oral cavity, but it is still debated whether the activity of type III cells promotes preference or avoidance by itself. This may stem from the possible heterogeneity of type III cells, but their scarcity has made it hard to unveil the truth.

DEDICATED RESPONSES OF THE GENICULATE GANGLION

Early single-fiber nerve recordings as well as recent in vivo Ca2+ imaging techniques have shown the dedicated responses of primary gustatory neurons to each taste modality [43–45], which implies the existence of selective connections between taste-responsive cells in taste buds and primary gustatory neurons. Therefore, taste-responsive cells for each modality require molecular machinery for exclusive synapses to the corresponding neurons.

Recently, the Zuker group demonstrated that several semaphorins (SEMAs), as a subcategory of cell adhesion molecules, are responsible for the precise innervation of gustatory neurons into taste buds in a modality-specific manner (Fig. 2B) [46]. SEMA expression differs depending on cellular modality type, with SEMA7A found in sweet taste cells and SEMA3A in bitter taste cells. Genetic depletion of each SEMA disrupts both taste-guided behaviors and the modality-specific responses of the ganglion. Moreover, ectopic expression of human SEMA7A in sour cells transmitted sour signals into a sweet-dedicated ganglion, confirming the role of the SEMA system in wiring epithelial cells to neurons. Given that SEMAs are secreted from taste bud cells, specific binding partners should be expressed in each type of neuron. These findings imply that primary gustatory neurons show considerable molecular heterogeneity.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) enabled classification of entire population of neurons of the geniculate ganglion based on transcriptomic profiles [37,47]. Gustatory neurons are not only molecularly isolated from the somatosensory components of the auriculotemporal nerve [47], but are also divided into five classes corresponding to each taste modality [37]. Indeed, the Zuker group identified specific markers for each group: Spondin1 for sweet; Cdh4 for umami; Cdh13 for bitter; Penk for sour; and Egr2 for salty taste. They created KO mice and transgenic mice carrying Cre for each marker, observing behavioral defects and selective responses of the labeled ganglia, respectively [37]. Therefore, it was confirmed that the relay of information for each taste modality is genetically defined at the entrance of the neural network.

HORMONAL EFFECTS ON TASTE PERCEPTION

Hormones are usually defined as chemical signals secreted into the bloodstream which act on distant tissues for their specific regulation. In addition to the primary ‘endocrine’ organs, taste buds also had been reported to express metabolic hormones such as vasoactive intestinal peptide and serotonin [48,49]. In the early 21st century, more evidence had accumulated that taste cells express several metabolic hormones and their relevant receptors. Accordingly, the concept has emerged that hormones can act on taste cells and, as a result, can affect taste perception in autocrine and/or paracrine manner. Several types of metabolic hormones expressed in taste cells had been studied, including neuropeptide Y (NPY) and cholecystokinin (CCK) [50,51]. Similar to the diametrical roles of anorexigenic CCK and orexigenic NPY in energy metabolism [52], they also have opposite effects on potassium current in taste cells [53]. Resulting amplification of bitter taste perception against sweet taste perception are assumed not to pass over bitter-tasting toxins, which can be an example of regulation of taste decoding in a coordinated manner.

In the past decade, more hormones and/or their receptors have been discovered in taste cells, and their roles in taste decoding by modulating intracellular signaling have been delineated. Glucagon enhances sweet taste, which is similar to glucagon-like peptide-1, another cleavage product generated from a proglucagon peptide [54,55]. Ghrelin reduces salty and sour taste responsivity [56]. Angiotensin inhibits salty taste and enhances sweet taste sensitivities [57] while leptin selectively suppresses neural and behavioral responses to sweet taste [58]. Various research groups have tried to define the expression patterns and roles in taste perception of the hormones, which are well described in other review articles [59,60].

Conversely, regulation of synthesis and secretion of hormones from taste buds has been unclear yet. Considering that nutrients and energy status regulate synthesis and secretion of metabolic hormones in major endocrine organs, it is plausible that each tastant also might facilitate hormonal expression and/or secretion in taste cells. Furthermore, the taste buds derived-hormones might affect systemic metabolism. Cephalic phases insulin responses might be the good example to support to this [61,62]. However, the extent of taste bud derived-hormones affecting at systemic levels should be re-examined. Taste buds are too tiny and limited in their number to study with conventional biochemical research methods, thus novel tools including organoids would serve as the alternatives in this field.

CONCLUSIONS

Although the discovery of CALHM1/3, Scnn1a, Otop1, and SEMA broadened the current understanding of peripheral taste decoding, several questions still remain. Are there any unidentified taste modalities like fat and starch? How many types of intragemmal cells can be classified according to the transcriptomic profile? What is the molecular mechanism of the differentiation of taste cells that respond to specific taste modalities? What is the effect of each taste stimulus on regulating the expression of each hormone in taste cells? Do knowledges of taste decoding obtained from animal experiments have human relevance? High-throughput scRNAseq for taste buds would be expected to resolve transcriptomic heterogeneity issues, illuminating unexpected and novel molecular pathways, and eventually helping to regulate feeding behaviors and metabolism in humans.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grants funded by the Korea Government (NRF-2016R1A5A2008630 to Seok Jun Moon, NRF-2020R1-A4A3078962 to Obin Kwon and NRF-2019R1C1C1006751 and NRF-2020R1A4A3078962 to Yong Taek Jeong), by Creative-Pioneering Researchers Program through Seoul National University (to Obin Kwon), and by Korea University Grant (K1923721 to Yong Taek Jeong).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Farbman AI. Fine structure of the taste bud. J Ultrastruct Res. 1965;12:328–50. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(65)80103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinnamon JC, Sherman TA, Roper SD. Ultrastructure of mouse vallate taste buds: III. Patterns of synaptic connectivity. J Comp Neurol. 1988;270:1–10. 56–7. doi: 10.1002/cne.902700102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson G, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Zhang Y, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. Mammalian sweet taste receptors. Cell. 2001;106:381–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson G, Chandrashekar J, Hoon MA, Feng L, Zhao G, Ryba NJ, et al. An amino-acid taste receptor. Nature. 2002;416:199–202. doi: 10.1038/nature726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrashekar J, Mueller KL, Hoon MA, Adler E, Feng L, Guo W, et al. T2Rs function as bitter taste receptors. Cell. 2000;100:703–11. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80706-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao GQ, Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Erlenbach I, Ryba NJ, et al. The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste. Cell. 2003;115:255–66. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLaughlin SK, McKinnon PJ, Margolskee RF. Gustducin is a taste-cell-specific G protein closely related to the transducins. Nature. 1992;357:563–9. doi: 10.1038/357563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz-Avila L, McLaughlin SK, Wildman D, McKinnon PJ, Robichon A, Spickofsky N, et al. Coupling of bitter receptor to phosphodiesterase through transducin in taste receptor cells. Nature. 1995;376:80–5. doi: 10.1038/376080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Mueller KL, Cook B, Wu D, et al. Coding of sweet, bitter, and umami tastes: different receptor cells sharing similar signaling pathways. Cell. 2003;112:293–301. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller KL, Hoon MA, Erlenbach I, Chandrashekar J, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ. The receptors and coding logic for bitter taste. Nature. 2005;434:225–9. doi: 10.1038/nature03352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang L, Shanker YG, Dubauskaite J, Zheng JZ, Yan W, Rosenzweig S, et al. Ggamma13 colocalizes with gustducin in taste receptor cells and mediates IP3 responses to bitter denatonium. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1055–62. doi: 10.1038/15981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hisatsune C, Yasumatsu K, Takahashi-Iwanaga H, Ogawa N, Kuroda Y, Yoshida R, et al. Abnormal taste perception in mice lacking the type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37225–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang YA, Roper SD. Intracellular Ca(2+) and TRPM5-mediated membrane depolarization produce ATP secretion from taste receptor cells. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 13):2343–50. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutta Banik D, Martin LE, Freichel M, Torregrossa AM, Medler KF. TRPM4 and TRPM5 are both required for normal signaling in taste receptor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E772–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718802115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clapp TR, Yang R, Stoick CL, Kinnamon SC, Kinnamon JC. Morphologic characterization of rat taste receptor cells that express components of the phospholipase C signaling pathway. J Comp Neurol. 2004;468:311–21. doi: 10.1002/cne.10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang YJ, Maruyama Y, Dvoryanchikov G, Pereira E, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. The role of pannexin 1 hemichannels in ATP release and cell-cell communication in mouse taste buds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6436–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611280104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang YA, Maruyama Y, Roper SD. Norepinephrine is coreleased with serotonin in mouse taste buds. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13088–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4187-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang YJ, Maruyama Y, Lu KS, Pereira E, Plonsky I, Baur JE, et al. Mouse taste buds use serotonin as a neurotransmitter. J Neurosci. 2005;25:843–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4446-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finger TE, Danilova V, Barrows J, Bartel DL, Vigers AJ, Stone L, et al. ATP signaling is crucial for communication from taste buds to gustatory nerves. Science. 2005;310:1495–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1118435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taruno A, Vingtdeux V, Ohmoto M, Ma Z, Dvoryanchikov G, Li A, et al. CALHM1 ion channel mediates purinergic neurotransmission of sweet, bitter and umami tastes. Nature. 2013;495:223–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma Z, Taruno A, Ohmoto M, Jyotaki M, Lim JC, Miyazaki H, et al. CALHM3 is essential for rapid ion channel-mediated purinergic neurotransmission of GPCR-mediated tastes. Neuron. 2018;98:547–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park S, Williams KW, Liu C, Sohn JW. A neural basis for tonic suppression of sodium appetite. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23:423–32. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0573-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandrashekar J, Kuhn C, Oka Y, Yarmolinsky DA, Hummler E, Ryba NJ, et al. The cells and peripheral representation of sodium taste in mice. Nature. 2010;464:297–301. doi: 10.1038/nature08783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oka Y, Butnaru M, von Buchholtz L, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. High salt recruits aversive taste pathways. Nature. 2013;494:472–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garty H. Molecular properties of epithelial, amiloride-blockable Na+ channels. FASEB J. 1994;8:522–8. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.8.8181670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lossow K, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Meyerhof W, Behrens M. Segregated expression of ENaC subunits in taste cells. Chem Senses. 2020;45:235–48. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjaa004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nomura K, Nakanishi M, Ishidate F, Iwata K, Taruno A. All-electrical Ca2+-independent signal transduction mediates attractive sodium taste in taste buds. Neuron. 2020;106:816–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tordoff MG, Ellis HT, Aleman TR, Downing A, Marambaud P, Foskett JK, et al. Salty taste deficits in CALHM1 knockout mice. Chem Senses. 2014;39:515–28. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bju020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behrens M, Redel U, Blank K, Meyerhof W. The human bitter taste receptor TAS2R7 facilitates the detection of bitter salts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;512:877–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.03.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Zajac AL, Lei W, Christensen CM, Margolskee RF, Bouysset C, et al. Metal ions activate the human taste receptor TAS2R7. Chem Senses. 2019;44:339–47. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjz024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roebber JK, Roper SD, Chaudhari N. The role of the anion in salt (NaCl) detection by mouse taste buds. J Neurosci. 2019;39:6224–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2367-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang YA, Maruyama Y, Stimac R, Roper SD. Presynaptic (Type III) cells in mouse taste buds sense sour (acid) taste. J Physiol. 2008;586:2903–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.151233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kataoka S, Yang R, Ishimaru Y, Matsunami H, Sevigny J, Kinnamon JC, et al. The candidate sour taste receptor, PKD2L1, is expressed by type III taste cells in the mouse. Chem Senses. 2008;33:243–54. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjm083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang AL, Chen X, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Guo W, Trankner D, et al. The cells and logic for mammalian sour taste detection. Nature. 2006;442:934–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zocchi D, Wennemuth G, Oka Y. The cellular mechanism for water detection in the mammalian taste system. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:927–33. doi: 10.1038/nn.4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson CE, Vandenbeuch A, Kinnamon SC. Physiological and behavioral responses to optogenetic stimulation of PKD2L1+ type III taste cells. eNeuro. 2019;6 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0107-19.2019. ENEURO.0107-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Jin H, Zhang W, Ding C, O’Keeffe S, Ye M, et al. Sour sensing from the tongue to the brain. Cell. 2019;179:392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horio N, Yoshida R, Yasumatsu K, Yanagawa Y, Ishimaru Y, Matsunami H, et al. Sour taste responses in mice lacking PKD channels. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tu YH, Cooper AJ, Teng B, Chang RB, Artiga DJ, Turner HN, et al. An evolutionarily conserved gene family encodes proton-selective ion channels. Science. 2018;359:1047–50. doi: 10.1126/science.aao3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye W, Chang RB, Bushman JD, Tu YH, Mulhall EM, Wilson CE, et al. The K+ channel KIR2.1 functions in tandem with proton influx to mediate sour taste transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E229–38. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514282112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teng B, Wilson CE, Tu YH, Joshi NR, Kinnamon SC, Liman ER. Cellular and neural responses to sour stimuli require the proton channel Otop1. Curr Biol. 2019;29:3647–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandrashekar J, Yarmolinsky D, von Buchholtz L, Oka Y, Sly W, Ryba NJ, et al. The taste of carbonation. Science. 2009;326:443–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1174601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ninomiya Y, Tonosaki K, Funakoshi M. Gustatory neural response in the mouse. Brain Res. 1982;244:370–3. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barretto RP, Gillis-Smith S, Chandrashekar J, Yarmolinsky DA, Schnitzer MJ, Ryba NJ, et al. The neural representation of taste quality at the periphery. Nature. 2015;517:373–6. doi: 10.1038/nature13873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu A, Dvoryanchikov G, Pereira E, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. Breadth of tuning in taste afferent neurons varies with stimulus strength. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8171. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee H, Macpherson LJ, Parada CA, Zuker CS, Ryba NJP. Rewiring the taste system. Nature. 2017;548:330–3. doi: 10.1038/nature23299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dvoryanchikov G, Hernandez D, Roebber JK, Hill DL, Roper SD, Chaudhari N. Transcriptomes and neurotransmitter profiles of classes of gustatory and somatosensory neurons in the geniculate ganglion. Nat Commun. 2017;8:760. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01095-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nada O, Hirata K. The occurrence of the cell type containing a specific monoamine in the taste bud of the rabbit’s foliate papila. Histochemistry. 1975;43:237–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00499704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herness MS. Vasoactive intestinal peptide-like immunoreactivity in rodent taste cells. Neuroscience. 1989;33:411–9. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao FL, Shen T, Kaya N, Lu SG, Cao Y, Herness S. Expression, physiological action, and coexpression patterns of neuropeptide Y in rat taste-bud cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11100–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501988102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herness S, Zhao FL, Lu SG, Kaya N, Shen T. Expression and physiological actions of cholecystokinin in rat taste receptor cells. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10018–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-10018.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu JH, Kim MS. Molecular mechanisms of appetite regulation. Diabetes Metab J. 2012;36:391–8. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2012.36.6.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Herness S, Zhao FL. The neuropeptides CCK and NPY and the changing view of cell-to-cell communication in the taste bud. Physiol Behav. 2009;97:581–91. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elson AE, Dotson CD, Egan JM, Munger SD. Glucagon signaling modulates sweet taste responsiveness. FASEB J. 2010;24:3960–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-158105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shin YK, Martin B, Golden E, Dotson CD, Maudsley S, Kim W, et al. Modulation of taste sensitivity by GLP-1 signaling. J Neurochem. 2008;106:455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shin YK, Martin B, Kim W, White CM, Ji S, Sun Y, et al. Ghrelin is produced in taste cells and ghrelin receptor null mice show reduced taste responsivity to salty (NaCl) and sour (citric acid) tastants. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shigemura N, Iwata S, Yasumatsu K, Ohkuri T, Horio N, Sanematsu K, et al. Angiotensin II modulates salty and sweet taste sensitivities. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6267–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5599-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshida R, Noguchi K, Shigemura N, Jyotaki M, Takahashi I, Margolskee RF, et al. Leptin suppresses mouse taste cell responses to sweet compounds. Diabetes. 2015;64:3751–62. doi: 10.2337/db14-1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Calvo SS, Egan JM. The endocrinology of taste receptors. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:213–27. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rohde K, Schamarek I, Bluher M. Consequences of obesity on the sense of taste: taste buds as treatment targets? Diabetes Metab J. 2020;44:509–28. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2020.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glendinning JI, Frim YG, Hochman A, Lubitz GS, Basile AJ, Sclafani A. Glucose elicits cephalic-phase insulin release in mice by activating KATP channels in taste cells. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2017;312:R597–R610. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00433.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doyle ME, Fiori JL, Gonzalez Mariscal I, Liu QR, Goodstein E, Yang H, et al. Insulin is transcribed and translated in mammalian taste bud cells. Endocrinology. 2018;159:3331–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2018-00534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]