Abstract

Multiple chronic conditions (i.e., multimorbidity) increase a person’s depressive symptoms more than having one chronic condition. Little is known regarding whether multimorbidity similarly increases the depressive symptoms of one’s spouse and whether this depends on type of condition, gender, or both spouses’ health status. Analysis of multiple waves of the Health and Retirement Study reveals husband’s number of chronic conditions is positively related to wife’s depressive symptoms when both spouses are chronically ill. The association between wife’s chronic conditions and husband’s depressive symptoms is weaker and less robust. Type of chronic condition also matters but which type depends on the gender and health status of both spouses. By highlighting key contexts where chronic conditions are connected to spousal depressive symptoms, this study identifies areas of vulnerability and urges researchers and clinicians to consider multimorbidity when designing and implementing interventions, along with gender, both spouses’ chronic conditions, and condition type.

Keywords: chronic conditions, depressive symptoms, dyadic analysis, gender, marriage

Chronic conditions negatively impact mental and emotional well-being (Fiest et al. 2011; Hollingshaus and Utz 2013; Pudrovska 2010). Older adults often experience multiple conditions simultaneously (i.e., multimorbidity; Freid, Bernstein, and Bush 2012), and the mental health impact of a chronic condition is exacerbated with each additional chronic condition (Barnett et al. 2012, Fortin et al. 2006), in part because multimorbidity requires complex medical care, increases health care costs, and contributes to more disabilities and pain (Fortin et al. 2007; Glynn et al. 2011; Marengoni et al. 2011). Past studies demonstrate that having a spouse with a chronic condition increases one’s own depressive symptoms (for overview, see Berg and Upchurch 2007); however, these studies largely overlook multimorbidity, focusing instead on only one type of chronic condition (e.g., cancer) or the presence or absence of any chronic conditions (Ayotte, Yang, and Jones 2010; Berg and Upchurch 2007; Franks et al. 2010; Goldzweig et al. 2009; Northouse et al. 2000; Ruthig, Trisko, and Stewart 2012). This present study anticipates that the more chronic conditions a person has, the more depressive symptoms his or her spouse will have, net of that spouse’s own depressive symptoms.

Further, often overlooked is whether this association depends on type of condition, health status of both spouses (e.g., whether one or both spouses have chronic conditions), and/or gender. Gender shapes diagnoses and experiences of chronic conditions, including likelihood of multimorbidity, type of condition encountered, and number of depressive symptoms, as well as processes within marriage (Anderson and Horvath 2004; Case and Paxson 2005; Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton 2001). Thus, gender likely influences the association between multimorbidity and spouse’s depressive symptoms. Past studies that do not consider number of chronic conditions likely overestimate the role of gender in the association between one spouse’s chronic condition and the other spouse’s depressive symptoms. Gender differences may be exacerbated in the case of multimorbidity, which requires even more intensive caregiving and is thus likely to more negatively impact wives because they tend to engage in more caregiving than husbands (Barnett et al. 2012; Fortin et al. 2006). Gender differences may also be more pronounced when both spouses are ill compared to only one spouse. Research shows that women in particular are less likely to adopt the “sick role” and care for themselves during illness (Gove 1984; Thomeer, Reczek, and Umberson 2015), perhaps leading to even greater depressive symptoms for wives when both spouses are ill as wives are attempting to care for their spouse and neglecting their own well-being.

This study considers how depressive symptoms are influenced by a spouse’s number of chronic conditions by analyzing longitudinal data using actor-partner interdependence models (APIMs) and dyadic latent growth curve models to explore unfolding linkages between one spouse’s number of chronic conditions and the other spouse’s depressive symptoms. Three specific questions are addressed:

Are a person’s depressive symptoms at one point in time and the trajectory of change in these depressive symptoms over time related to the number of chronic conditions of his or her spouse, net of that spouse’s own depressive symptoms?

Are a person’s depressive symptoms at one point in time and the trajectory of change in depressive symptoms over time related to the type of chronic conditions of his or her spouse, taking into account his or her number of conditions and net of that spouse’s own depressive symptoms?

Are these associations reciprocal processes in which both partners are equally influential or asymmetric processes moderated by gender?

Each of these questions is examined using three analytic samples: couples in which only the husband has chronic conditions, couples in which only the wife has chronic conditions, and couples in which both spouses have chronic conditions. In empirically testing these questions, this study draws on a developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic conditions (Berg and Upchurch 2007) and argues that chronic conditions, which are rapidly increasing in the population, create new stress in marital relationships and that the depressive symptoms produced by this stress differ for husbands compared to wives. This project represents an important and understudied dimension of gender and health disparities within marriage, considering how the physical health and mental health of both spouses are importantly connected in the case of multimorbidity.

BACKGROUND

Developmental-contextual Model of Couples Coping with Chronic Conditions

Past studies identify that chronic conditions contribute to increased depressive symptoms, not only for the person diagnosed with the chronic condition but also for his or her spouse (see overview in Berg and Upchurch 2007). The developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic conditions, formulated by Berg and Upchurch (2007), proposes that within marriage, the mental health impact of having a chronic condition is shared across spouses, with spouses’ reactions to their own or their spouse’s chronic condition affecting their spouse’s psychological state. Scholars identify that spouses of people with chronic conditions are “hidden patients,” as they are typically overlooked even though their mental (and even physical) health is often impaired from their spouse’s chronic conditions (Rohrbaugh et al. 2002). There are multiple ways in which one spouse’s chronic conditions may impact the other spouse’s depressive symptoms, including caregiving, fear of spouse’s death, lower marital quality, and stress from providing social control (Franks et al. 2010; Martire et al. 2010; Rohrbaugh et al. 2002; Rook et al. 2011). Additionally, spouses share environments and risk factors (e.g., low socioeconomic status), which can contribute to one spouse’s chronic conditions impacting the other spouse’s depressive symptoms.

These processes may be more pronounced in the context of multimorbidity. Multimorbidity contributes to longer hospital stays, more medical complications, higher health care costs, and greater risk of mortality than only having one condition (Fortin et al. 2007; Glynn et al. 2011; Marengoni et al. 2011). Thus, not surprisingly, multimorbidity lowers quality of life and increases depressive symptoms for the chronically ill person (Barnett et al. 2012; Fortin et al. 2006). Most past empirical studies of multimorbidity and mental health focus on individuals, rather than a dyadic approach, overlooking the ways in which depressive symptoms are shared by and spread within couples (for overview, see Berg and Upchurch 2007). Just as depressive symptoms are higher for people with multimordibity compared to people with only one chronic condition, it is likely that depressive symptoms are higher for spouses of people with multiple chronic conditions compared to spouses of people with only one chronic condition, increasing with each additional condition.

The association between one spouse’s chronic conditions and the other spouse’s depressive symptoms likely unfolds longitudinally, such that as a chronic condition develops and progresses, stressors (e.g., difficulties with activities of daily living, financial strain, doctor visits, pain management, caregiving burdens) multiply and intensify, and the trajectory of depressive symptoms related to the condition builds (Helgeson, Snyder, and Seltman 2004). Further, according to the developmental-contextual model (Berg and Upchurch 2007), this association is context dependent. In addition to multimorbidity, this present study considers three key contexts that likely impact the association between one spouse’s chronic conditions and the other spouse’s depressive symptoms: type of condition, the health status of both spouses, and gender.

Type of Condition

Beyond a simple count of number of conditions, type of condition is also likely important to consider as the type of chronic condition encountered may be associated with different trajectories of depressive symptoms, reflecting epidemiologic differences in who gets each condition, how severe each condition is, and the lifestyle changes and health care related to each condition. There are multiple types of chronic conditions with a wide diversity of symptoms and characteristics (Anderson and Horvath 2004). A diagnosis of heart disease may be more depressing than a diagnosis of arthritis because heart disease likely leads to more worry about death. But daily life with arthritis may be more disruptive than some types of heart disease that do not require lifestyle changes. Relatedly, some conditions may have greater negative psychological impact on spouses than others, requiring more care or promoting more worry. Yet most studies of chronic conditions and spouse’s depressive symptoms either do not distinguish between types of conditions or consider only one type of condition, not comparing spouse’s depressive symptoms across types of conditions (Ayotte et al. 2010; Berg and Upchurch 2007; Goldzweig et al. 2009; Northouse et al. 2000; Ruthig et al. 2012). Examining multiple types of chronic conditions separately but within the same study, also taking into account number of conditions, enables the consideration of the unique character of each condition and its implications for the depressive symptom dynamics within marriage.

Health Status of Both Spouses

For many couples, both spouses have multiple chronic conditions simultaneously, yet most past studies focus on one spouse and do not consider the chronic conditions of the other (for overview, see Berg and Upchurch 2007). Multimorbidity likely influences spouses’ depressive symptoms differently depending on the health status of both spouses. When both spouses have chronic conditions, it may be that neither spouse is impacted by his or her spouse’s conditions above and beyond his or her own conditions. Alternatively, when both spouses have chronic conditions, both spouses’ depressive symptoms may be worsened due to the burden of dealing with their spouse’s chronic conditions as well as their own. Not taking into account the chronic conditions of both spouses leads to an overestimation of the influence of one spouse’s chronic conditions on the other spouse’s mental health.

Gender

Most past studies with dyadic approaches to chronic conditions and depressive symptoms are restricted to samples of only men with chronic conditions, only women with chronic conditions, or do not compare across gender (see Berg and Upchurch 2007). The studies that do consider gender find inconsistent results, with some concluding that husbands of women with chronic conditions are more affected in terms of their mental health than are wives of men with chronic conditions (Baider and De-Nour 1999; Goldzweig et al. 2009), others finding the opposite (Ayotte et al. 2010; Rohrbaugh et al. 2002; Valle et al. 2013), and others observing no gender difference (Northouse et al. 2000; Ruthig et al. 2012).

Drawing on an extensive literature on gender within marriage, chronic conditions, and caregiving, this study expects that women will be more negatively affected by a spouse’s multimorbidity than men. Heterosexual marriage is a gendered institution, composed of a man and a woman, and is a primary site for the production and reproduction of gender (Reczek and Umberson 2012). For many couples, the organization of labor within the home is shaped by these constructions of masculinities and femininities, with women being primarily responsible for caregiving (England 2005). According to the nurturant role hypothesis, women are more likely to be nurturers (i.e., provide care work and emotion work) for their family members and more attentive to their relationships, both daily and during periods of chronic conditions—their own or their spouses (Gove 1984; Thomeer et al. 2015). Scholars argue that discrepancies in caregiving contribute to women’s higher levels of depressive symptoms (Gove 1984; Rosenfield, Lennon, and White 2005; Thomeer et al. 2015; Yee and Schulz 2000), and this may be particularly exacerbated with each additional chronic condition. Men, on the other hand, provide less emotional support (Umberson et al. 1996; Umberson, Thomeer, and Lodge 2015), including during chronic conditions (Thomeer et al. 2015), partially due to the socially constructed expectation that men are emotionally incompetent and less influenced by interpersonal stress (Thomeer, Umberson, and Pudrovska 2013). Consequently, past studies find that caregiving men have fewer depressive symptoms than caregiving women, even when providing similar levels of care (Pinquart and Sorensen 2006; Yee and Schulz 2000).

Chronic conditions are not randomly distributed, but rather, some types of conditions are more common and/or serious among men and others among women. This occurs for biological, social, and psychosocial reasons (Emslie, Hunt, and Watt 2001). Consequently, the impact of different numbers and types of chronic conditions, both for the person with the condition and his or her spouse, likely differs according to the gender of the person with the condition and the type of condition considered. For example, arthritis is more prevalent and severe in women than in men at all age groups (Barbour et al. 2011), whereas lung disease is more common and more serious among men than among women (Carey et al. 2007). Less common conditions for certain genders may actually be more distressing for those marriages due to these conditions being less normative. Additionally, different chronic conditions disrupt daily lives in gendered ways (e.g., joint pain from arthritis might affect housework, a task more often done by women) and thus may have different consequences for men and women.

Present Study

Drawing on past literature, this study hypothesizes that the more chronic conditions a person has, the more depressed his or her spouse will be, adjusting for the chronically ill spouse’s own depressive symptoms. Because spouses’ depressive symptom levels are associated across time (Siegel et al. 2004; Thomeer et al. 2013), the analytic strategy takes both spouses’ depressive symptoms into account by using APIMs. This study also uses dyadic growth curve models. The negative impact of chronic conditions may build over time—for example, some chronic conditions may not require intensive caregiving in the beginning stages—and growth curve models are able to consider the importance of time in the association between chronic conditions and spouse’s depressive symptoms. As an additional strength, this study also considers whether this association differs depending on type of condition, gender, and whether both spouses are chronically ill or only one spouse is chronically ill.

DATA AND METHODS

Data

This study analyzed 1998 to 2010 data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative sample of primary respondents ages 51 to 61 years in 1992 and their spouses (any age), with different cohorts and ages added at later waves. At baseline in this present analysis, respondents and spouses ranged in age from 27 to 99 years, with fewer than 5% of respondents younger than 50. The RAND HRS data, provided by the RAND Center for the Study of Aging, was used (RAND HRS Data 2010). Response rates across waves ranged from 80% to 90%.

These data are ideal for this study for three main reasons. First, the HRS is a large and nationally representative data set. It uses a multistage, clustered area probability frame in order to generate a representative sample, oversampling married couples. Most prior studies of chronic conditions and depressive symptoms within marriage have depended on small, nonrepresentative sample sizes, rarely including more than 100 couples (for overview, see Berg and Upchurch 2007). Using a large, nationally representative data set allowed for examination of stratified samples and tests of models across and within groups—possibilities that are limited with smaller samples. Second, the HRS is longitudinal; respondents are reinterviewed approximately every two years (Juster and Suzman 1995). Because of the expectation that depressive symptom processes around chronic conditions unfold over time, using longitudinal data was critical. Third, both respondents and their spouses are interviewed, making dyadic data analysis of this data set possible. This point was key, as the analysis hinged on examining the lived experiences of both husbands and wives within marriage.

Three analytic samples were constructed. All three samples were limited to married couples in which both spouses were interviewed and at least one spouse had any chronic conditions in at least three waves, with Wave 4 (i.e., 1998) being the first eligible wave and Wave 10 (i.e., 2010) being the last eligible wave. The sample was restricted to couples interviewed for at least three waves in order to take advantage of the longitudinal aspect of this study. Sensitivity analysis demonstrated that results were not statistically or substantively altered when using criteria of two, four, or five waves. Further, the sample was restricted to Wave 4 and later because this wave was the first wave when all cohorts were included. The first analytic sample was composed of couples in which the wife had any chronic conditions for three consecutive waves but the husband did not have any chronic conditions during that period (n = 791 couples). The second analytic sample was composed of couples in which the husband had any chronic conditions for three consecutive waves but the wife did not have any chronic conditions during that period (n = 951 couples). The third analytic sample is composed of couples in which both the husband and the wife had any chronic conditions for three consecutive waves (n = 4,892 couples).

Measures

Number and Type of Chronic Conditions.

For this study, number of chronic conditions was assessed in two ways: number of chronic conditions ever diagnosed and number of chronic conditions currently being treated. For number of conditions ever diagnosed, in the respondents’ first interview, they were asked: “Has the doctor ever told you that you have... (1) high blood pressure or hypertension; (2) diabetes or high blood sugar; (3) cancer or a malignant tumor of any kind except skin cancer; (4) chronic lung disease except asthma such as chronic bronchitis or emphysema; (5) heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems; (6) stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA); and (7) arthritis or rheumatism?” In subsequent interviews, they were asked, “Since we last talked to you, that is since [last interview date], has a doctor told you that have...?” followed by the same list of conditions. The conditions were summed for each wave, and number of chronic conditions ranges from zero to seven. Self-reports of health problems in the HRS corresponded with clinical diagnosis (for example, 90% to 95% accuracy for cancer and diabetes; Hayward 2002).

For number of chronic conditions currently being treated, for each chronic condition respondents reported having, respondents and spouses were asked about current drugs and treatments for that condition. For example, respondents were asked if they are currently taking drugs to manage their high blood pressure and if they were currently using oxygen therapy for their lung disease. Respondents were asked about drugs or treatments for each of the seven chronic conditions, and the number of conditions for which they receive any treatments or drugs was summed, ranging from 0 to 7.

These same measures were used for type of condition, except rather than summing the number of conditions, chronic conditions were treated categorically (1 = high blood pressure, 2 = diabetes, 3 = cancer, 4 = chronic lung disease, 5 = heart disease, 6 = stroke, and 7 = arthritis). These categories were not mutually exclusive. As with number of chronic conditions, models were fit using ever being diagnosed with a particular condition and currently being treated for a particular condition. When type of condition was examined as the predictor variable, high blood pressure was excluded, as including all seven conditions results in an overspecified model. Rotating which chronic condition was excluded demonstrated no difference in results.

Depressive Symptoms.

The mental health index provided by the HRS used eight items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977). These items measured whether the respondent experiences the following all or most of the time: feels depressed, feels everything is an effort, has restless sleep, feels alone, feels sad, cannot get going, feels happy, and enjoys life. The items were coded so that higher values reflect more depressive symptoms and range from 0 to 8. This short version of the CES-D had predictive accuracy when compared to the full-length form, correlated well with poor mental health, and had good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .78 (Andreson et al. 1994, Grzywacz et al. 2006).

Gender.

Gender of the respondent and spouse was self-reported as male or female. For ease of discussion, male was used interchangeably with man and husband, and female was used interchangeably with woman and wife.

Control Variables.

Other controls included age of respondent (in years, calculated using birth year and year of interview), age of spouse, marital duration (in years), educational attainment (in years), race-ethnicity (dummy variables with four mutually exclusive categories: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other), number of living children, log of household income, and disabilities. All were included as control variables because past research shows that each is associated with depressive symptoms and chronic conditions (Keles et al. 2006; Mirowsky and Ross 2003). Disabilities were measured using self-reported activity of daily living (ADL) difficulties and instrumental ADL (I-ADL) difficulties, combined into one ADL/I-ADL index, as this has been shown to be less biased by age than either index separately (LaPlante 2010). The ADL difficulty score referred to the number of ADLs the respondent reported having some difficulties with, namely, bathing, eating, dressing, walking across a room, and getting in or out of bed. This is a scale from 0 to 5. The I-ADL score was the number of I-ADLs the respondent reported having some difficulties with, including using a telephone, taking medication, and handling money. This is a scale from 0 to 3.

Supplementary analysis (not shown) examined whether helping a spouse with ADL/I-ADL difficulties—a proxy for caregiving—mediated the relationship between number of conditions and depressive symptoms. This was examined using a dichotomous measure (any help or no help) and a continuous measure (number of ADL/I-ADL difficulties receives help with). The results demonstrated that including this measure does not improve the models or significantly change the coefficients above and beyond considering disabilities; thus these results were not presented.

Analysis

APIMs and dyadic latent growth curve models were used (Kenny, Kashy, and Cook 2006). Kenny and colleagues (2006:367) argued that APIM and growth curve modeling were not competing methods but should be used to “address different, complementary questions” and can thus “be profitably combined.” The specific type of APIM used in this study—autoregressive path models—examines consistency of associations across time points, while latent growth curve models examine change over time. The APIM was also beneficial as it takes into account the nonindependence of measures between spouses.

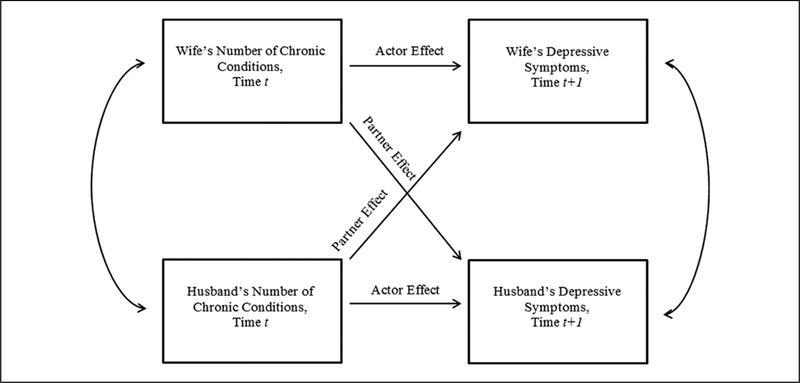

Autoregressive path models involve past values of one variable predicting future values of a different variable, allowing for estimation of simultaneously linear relationships among various combinations of observed variables and providing simultaneous estimation of the influence of different pathways on the coefficients (Kline 2011). The basic model for this study is shown in Figure 1. Two baseline models were fit:

Figure 1.

Actor–Partner Interdependence Model for One Spouse’s Number of Chronic Conditions on Other Spouse’s Depressive Symptoms.

Model testing the influence of wife’s chronic conditions on husband’s depressive symptoms, controlling for wife’s depressive symptoms at each time point, and

Model testing the influence of husband’s chronic conditions on wife’s depressive symptoms, controlling for husband’s depressive symptoms at each time point.

These models were fit separately with three different predictor variables: (1) number of chronic conditions ever diagnosed (controlling for number of current drugs/treatments), (2) number of chronic conditions currently being treated, and (3) type of chronic conditions currently being treated (controlling for number of chronic conditions ever diagnosed). Each model was fit separately using the sample of couples in which only one spouse has any chronic conditions and using the sample of couples in which both the husband and the wife have any chronic conditions. For the sample of couples in which both spouses have chronic conditions, the models controlled for the other spouse’s chronic conditions.

Additionally, linear growth curve models were estimated to assess the association of chronic conditions of one spouse on initial level and change in the number of depressive symptoms of the other spouse over time. George and Lynch (2003) argue that growth curve models are the ideal method to examine the initial impact of stressful life events and the subsequent unique depressive symptom trajectories. Growth curve models distinguish within-individual heterogeneity from between-individual heterogeneity in estimating depressive symptom changes shaped by other variables (Kenny et al. 2006). Dyadic growth curve models allowed both members of the dyad (e.g., husband and wife) to have their own intercepts and slopes with these values allowed to correlate across the dyad (Kenny et al. 2006). Various shapes of number of conditions and CES-D trajectories were tested, including linear, quadratic, and cubic models. Models were compared using nested likelihood ratio tests, and comparisons revealed that a linear growth curve with random intercepts and random linear time slopes were the best fit for the data. Four models were fit. First, the association between wife’s number of chronic conditions (intercept and slope) and the intercept and slope of the husband’s depressive symptoms in couples in which only the wife has any chronic conditions was estimated, controlling for wife’s depressive symptoms. Second, the association between the husband’s number of chronic conditions (intercept and slope) and the intercept and slope of the wife’s depressive symptoms in couples in which only the wife has any chronic conditions was estimated, controlling for husband’s depressive symptoms. These two models were then repeated with couples in which both the wife and husband have chronic conditions, controlling for both spouses’ number of conditions in both models. Number of conditions ever diagnosed and number of conditions currently being treated were assessed separately. To consider type of condition, the association one spouse’s type of chronic conditions at baseline and the intercept and slope of the other spouse’s depressive symptoms in each of the three subsamples was estimated. Each of these models was estimated for conditions ever diagnosed and conditions currently being treated.

For both the autoregressive models and the latent growth curve models, multiple-group analysis was used to test whether the association between one spouse’s conditions and the other spouse’s CES-D score differed when looking at husbands compared to wives. This was able to be done only with the third analytic sample, as the first and second analytic samples are not composed of the same couples. This comparison was conducted by analyzing a model where the relationship between one spouse’s conditions and the other spouse’s CES-D score was constrained to be equal across gender groups and a model where the effects were estimated freely across gender groups. A significant improvement in the chi-square statistic from the restricted to the unrestricted model indicated significant differences across the groups. Interactions between gender and number of conditions were also examined. These tests confirmed that the gender differences reported were statistically significant.

All analyses were conducted in MPlus (Muthén and Muthén 2010). Mplus uses full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedures to deal with missing data. Maximum likelihood parameter estimates with conventional standard errors and chi-square test statistics were used. FIML has been shown to minimize bias and maximize efficiency when dealing with missing data (Schafer and Graham 2002). Goodness-of-fit measures with the Akaike information criterion and the Bayesian information criterion are presented.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of variables at baseline, comparing men and women within each subsample (only wife with chronic conditions, only husband with chronic conditions, and both spouses with chronic conditions) as well as a subsample of couples with no chronic conditions for at least three waves. Table 2 shows type of condition (whether ever diagnosed and whether currently receiving drugs or treatments for that condition) within each subsample by gender of respondent. Statistical significance tests were conducted to compare variables across each subsample and by gender within each subsample. All differences discussed are significant at p < .05. In couples in which only the wife has chronic conditions, couples in which both spouses have chronic conditions, and couples in which neither spouse has chronic conditions, women have significantly higher CES-D scores than men. There is no significant difference between men and women in depressive symptoms for the couples in which only the husband has chronic conditions. In the couples in which both spouses have chronic conditions, husbands have on average more conditions than wives, partly reflecting men’s older age. Couples in which both spouses have a chronic condition are on average older than couples in which only one spouse has a chronic condition and couples in which neither spouse has a chronic condition. Number of chronic conditions and CES-D scores increase over time (not shown). Arthritis is the most prevalent condition ever diagnosed for women, and high blood pressure is the most prevalent condition ever diagnosed for men.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Variables at Baseline, Health and Retirement Study, N = 6,904.

| Variable | Only Wife with Chronic Conditions n = 791 |

Only Husband with Chronic Conditions n = 951 |

Both Spouses with Chronic Conditions n = 4,892 |

Neither Spouse with Chronic Conditions n= 270 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| CES-D | .83 (1.38) |

1.58 (2.02) |

.97 (1.48) |

.92 (1.50) |

1.13 (1.61) |

1.51 (1.92) |

.75 (1.36) |

.94 (1.58) |

| Number of chronic conditions | — | 1.49 (.79) |

1.55 (.80) |

— | 1.81 (.96) |

1.69 (.91) |

— | — |

| Age (years) | 6.30 (9.03) |

58.32 (8.73) |

61.33 (8.11) |

56.54 (9.09) |

65.75 (8.74) |

62.52 (8.99) |

56.61 (7.34) |

52.90 (7.92) |

| Marital duration (years) | 3.40 (14.08) |

29.03 (14.15) |

34.83 (14.91) |

24.10 (12.93) |

||||

| Years of education | 12.92 (3.48) |

12.70 (3.19) |

13.21 (3.28) |

13.11 (2.72) |

12.27 (3.44) |

12.38 (2.90) |

13.83 (3.76) |

13.36 (3.42) |

| Number of living children | 3.24 (2.04) |

3.35 (2.07) |

3.52 (2.20) |

2.88 (1.72) |

||||

| Race-ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | .76 | .76 | .81 | .80 | .80 | .80 | .77 | .75 |

| Non-Hispanic black | .09 | .10 | .07 | .07 | .11 | .11 | .05 | .05 |

| Hispanic | .12 | .12 | .10 | .10 | .08 | .08 | .14 | .16 |

| Other | .02 | .02 | .02 | .03 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .04 |

| Household income ($) | 81,619 (89,111) |

102,648 (433,121) |

65,575 (156,667) |

1 12,269 (136,515) |

||||

| Number of disabilities | .22 (.75) |

.15 (.62) |

.30 (.93) |

.30 (.91) |

||||

| Number of drugs/treatments | .85 (.80) |

.92 (.80) |

1.12 (.92) |

1.03 (.88) |

||||

Note: Cells contain standard errors in parentheses. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of Type of Chronic Condition, Health and Retirement Study, N = 6,634 Couples.

| Condition | Only Wife with Chronic Conditions n = 791 |

Only Husband with Chronic Conditions n = 951 |

Both Spouses with Chronic Conditions (Wife’s Condition) n = 4,892 |

Both Spouses with Chronic Conditions (Husband’s Condition) n = 4,892 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diag. | Drugs | Diag. | Drugs | Diag. | Drugs | Diag. | Drugs | |

| High blood pressure | .51 (.50) |

.42 (.49) |

.54 (.50) |

.43 (.50) |

.53 (.50) |

.46 (.50) |

.55 (.50) |

.47 (.50) |

| Arthritis | .57 (.50) |

.21 (.41) |

.45 (.50) |

.16 (.37) |

.66 (.47) |

.31 (.46) |

.54 (.50) |

.21 (.41) |

| Diabetes | .12 (.32) |

.10 (.30) |

.16 (.37) |

.13 (.34) |

.13 (.34) |

.11 (.31) |

.19 (.39) |

.16 (.36) |

| Cancer | .09 (.29) |

.02 (.13) |

.09 (.28) |

.01 (.11) |

.12 (.33) |

.02 (.13) |

.11 (.32) |

.02 (.14) |

| Lung disease | .04 (.21) |

.02 (.13) |

.05 (.21) |

.02 (.14) |

.06 (.24) |

.03 (.18) |

.07 (.26) |

.04 (.19) |

| Heart disease | .13 (.34) |

.08 (.26) |

.22 (.42) |

.15 (.35) |

.15 (.35) |

.09 (.28) |

.27 (.45) |

.19 (.39) |

| Stroke | .03 (.16) |

.01 (.10) |

.05 (.21) |

.02 (.14) |

.05 (.21) |

.02 (.13) |

.07 (.26) |

.03 (.18) |

Note: cells contain standard errors in parentheses. Diag. = ever diagnosed; Drugs = currently receiving drugs/treatment.

Number of Conditions

The APIMs in Table 3 and growth curve models in Table 4 show the estimated effects of one spouse’s number of chronic conditions on the other spouse’s CES-D score across time and the associated goodness-of-fit statistics for each subsample. Looking first at the APIMs in Table 3, husband’s number of chronic conditions ever diagnosed is consistently related to wife’s number of depressive symptoms in couples in which both spouses have chronic conditions (Model G). Similarly, husband’s number of current chronic condition treatments is consistently related to wife’s depressive symptoms in couples in which both spouses have chronic conditions (Model H). When only the husband is ill, there is no association between the husband’s number of chronic conditions ever diagnosed or current treatments at one time point and wife’s depressive symptoms at a future time point (Models C and D), nor is there a significant association between the wife’s number of chronic conditions ever diagnosed or currently being treated and husband’s depressive symptoms when both spouses are ill (Models E and F). When only the wife is chronically ill, number of wife’s chronic conditions ever diagnosed at Time 1 is positively related to husband’s depressive symptoms at Time 2 but not from Time 2 to Time 3 (Model A). Wife’s number of current treatments is not related to husband’s depressive symptoms at any time point in any subsample (Models B and F).

Table 3.

Summary of Fitted Model Coefficients for the Associations between Spouse A’s Chronic Conditions and Spouse B’s CES-D, Health and Retirement Study, N = 6,634 Couples.

| Only Spouse A with Chronic Conditions |

Both Spouses with Chronic Conditions |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spouse A = Wife; Spouse B = Husband (n = 791) |

Spouse A = Husband; Spouse B = Wife (n = 951) |

Spouse A = Wife; Spouse B = Husband (n = 4,892) |

Spouse A = Husband; Spouse B = Wife (n = 4,892) |

|||||

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | Model E | Model F | Model G | Model H | |

| Variable | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) |

| Spouse A’s number of chronic conditions (Time 1) on Spouse B’s CES-D (Time 2) | .13* (.06) |

.00 (.06) |

−.03 (.03) |

.08** (.03) |

||||

| Spouse A’s number of drugs/treatments (Time 1) on Spouse B’s CES-D (Time 2) | .09 (.12) |

−.01 (.05) |

−.02 (.03) |

.06* (.03) |

||||

| Spouse A’s number of chronic conditions (Time 2) on Spouse B’s CES-D (Time 3) | .08 (.17) |

.09 (.06) |

.00 (.03) |

.10*** (.03) |

||||

| Spouse A’s number of drugs/treatments (Time 1) on Spouse B’s CES-D (Time 2) | −.01 (.05) |

.10 (.06) |

−.03 (.03) |

.06* (.03) |

||||

| Model fit | ||||||||

| AIC | 13282.49 | 13284.57 | 15676.92 | 15676.01 | 73136.10 | 73135.89 | 76134.97 | 76143.77 |

| BIC | 13445.83 | 13447.91 | 15846.75 | 15845.83 | 73371.11 | 73370.90 | 76370.01 | 76378.80 |

Note: All models adjust for husband’s and wife’s age at interview, marital duration, educational attainment, race-ethnicity, number of living children, log of household income, number of disabilities, and CES-D. Cells contain standard errors in parentheses. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale; AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Table 4.

Couple-level Growth Curve Models Predicting Influence of One Spouse’s Number of Chronic Conditions on Other Spouse’s CES-D, Health and Retirement Study, N = 6,634 Couples.

| Variable | Only Wife with Chronic Condition (n = 791) |

Only Husband with Chronic Condition (n = 951) |

Wife and Husband with Chronic Condition (n = 4,892) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A |

Model B |

Model C |

Model D |

|||||

| Husband’s CES-D (1) | Husband’s CES-D (S) | Wife’s CES-D (1) | Wife’s CES-D (S) | Husband’s CES-D (1) | Husband’s CES-D (S) | Wife’s CES-D (1) | Wife’s CES-D (S) | |

| Husband’s number of conditions (I) | — | — | .04 (.07) |

−.01 (.02) |

— | — | .11** (.04) |

−.03*** (.01) |

| Husband’s number of conditions (S) | — | — | — | .03 (.07) |

— | — | — | (.04) |

| Wife’s number of conditions (I) | .01 (.08) |

−.01 (.01) |

— | — | .03 (.04) |

−.02***

(.00) |

— | — |

| Wife’s number of conditions (S) | — | .17* (.07) |

— | — | .08* (.04) |

— | — | |

| Residual variances | ||||||||

| I, CES-D | .55*** (.03) | 70*** (.08) | 1.19*** (.05) | 1.67*** (.07) | ||||

| S, CES-D | .03*** (.00) | .01 (.01) | .02*** (.00) | .03*** (.01) | ||||

| I, number of Conditions | .55*** (.03) | .58*** (.03) | .74*** (.01) | .88*** (.02) | ||||

| S, number of Conditions | .01** (.01) | .03*** (.02) | .03*** (.00) | .04*** (.00) | ||||

| Model fit | ||||||||

| AIC | 15058.97 | 19019.41 | 87079.81 | 90408.01 | ||||

| BIC | 15383.39 | 19349.99 | 87535.45 | 90855.04 | ||||

Note: Celis contain standard errors or variance in parentheses. All models adjust for husband’s and wife’s age at interview, marital duration, educational attainment, race-ethnicity, number of living children, log of household income, number of disabilities, and number of drugs/treatments. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale; I= intercept; S= slope; AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

p < .05

p < .01

p <.001.

In the growth curve analysis (see Table 4), which examines how change over time in one spouse’s chronic conditions is related to change in the other spouse’s depressive symptoms, the association between one spouse’s initial number of chronic conditions and the other spouse’s initial level of depressive symptoms (i.e., the intercepts) supports the results from the APIMs. Table 4 does not present results for number of current treatments as there are no significant associations between husband or wife’s initial number or change in number of treatments and spouse’s change in number of depressive symptoms. Among couples in which both spouses have chronic conditions, the slope of husband’s chronic conditions ever diagnosed is related to a steeper rate of growth of wife’s depressive symptoms (Model D), and the slope of wife’s chronic conditions ever diagnosed is related to a steeper rate of growth of husband’s chronic conditions (Model C). This slope is steeper when considering husband’s number of conditions on wife’s depressive symptoms than wife’s number of chronic conditions on husband’s depressive symptoms. Interestingly, in both cases, larger initial numbers of chronic conditions are associated with a negative slope for spouse’s depressive symptoms, though this coefficient is substantively small. Growth curve models also demonstrate that wife’s chronic conditions’ slope is positively associated with husband’s depressive symptoms’ slope in couples in which only the wife is chronically ill (Model A). In couples in which only the husband is chronically ill, there is no association between husband’s number of chronic conditions and wife’s depressive symptoms, initially or over time (Model B).

Types of Chronic Conditions

Next examined in Table 5 is the extent to which the type of chronic condition is related to the spouse’s depressive symptoms, controlling for number of chronic conditions using the three subsamples. APIMs and growth curve models showed similar results, though only growth curve models are presented in order to highlight the findings regarding change in depressive symptoms over time. Additionally, analysis indicates that results are similar whether considering type of conditions ever diagnosed or type of conditions currently receiving treatment, and thus only results for type of condition currently receiving treatment are presented. Growth curve models indicate that when the wife is being treated for lung disease and the husband has no chronic conditions, the husband’s initial depressive symptoms are about .66 units higher than when the wife is not being treated for lung disease (Model A). There are no other significant associations between wife’s type of condition and husband’s depressive symptoms when only the wife is chronically ill. When only the husband is chronically ill, the two types of conditions associated with wife’s depressive symptoms are diabetes and stroke. When the husband is being treated for diabetes and the wife has no chronic conditions, the wife’s depressive symptoms are about .41 units higher initially than if he is not being treated for diabetes (Model B). When the husband is being treated for stroke and the wife has no chronic conditions, the wife’s depressive symptoms are about .72 units higher initially than if he is not being treated for stroke (Model B).

Table 5.

Summary of Fitted Model Coefficients for the Associations between Spouse A’s Type of Chronic Conditions and Spouse B’s CES-D, Health and Retirement Study, N = 6,634 Couples.

| Only Spouse A with Chronic Conditions |

Both Spouses with Chronic Conditions |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A Spouse A = Wife; Spouse B = Husband (n = 791) |

Model B Spouse A = Husband; Spouse B = Wife (n = 951) |

Model C Spouse A = Wife; Spouse B = Husband (n = 4,892) |

Model D Spouse A = Husband; Spouse B = Wife (n = 4,892) |

|||||

| Condition | Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope |

| Arthritis | .00 (.13) |

.04 (.04) |

−.09 (.13) |

−.03 (.04) |

.14* (.07) |

−.02 (.02) |

.21* (.08) |

−.01 (.03) |

| Diabetes | .02 (.18) |

.02 (.05) |

41** (.14) |

−.01 (.05) |

.10 (.09) |

.03 (.03) |

.27** (.09) |

.03 (.03) |

| Cancer | −.07 (.34) |

.08 (.010) |

.17 (.35) |

−.09 (.11) |

.18 (.19) |

.00 (.06) |

.15 (.20) |

−.03 (.08) |

| Lung disease | .66* (.32) |

.17 (.12) |

.10 (.29) |

.05 (.09) |

.12 (.14) |

.00 (.04) |

.20 (.15) |

.13* (.05) |

| Heart disease | .31 (.19) |

.03 (.06) |

−.04 (.14) |

.03 (.04) |

.02 (.10) |

−.04 (.03) |

.09 (.09) |

.00 (.03) |

| Stroke | ||||||||

| Model fit | .15 (.43) |

−.05 (.11) |

.72* (.31) |

−.05 (.10) |

.15 (.18) |

.15* (.06) |

82*** (.16) |

−.06 (.05) |

| AIC | 13067.36 | 16637.43 | 70011.90 | 79297.47 | ||||

| BIC | 13277.66 | 16856.01 | 70310.76 | 79596.33 | ||||

Note: All models adjust for husband’s and wife’s number of conditions, age at interview, marital duration, educational attainment, race-ethnicity, number of living children, log of household income, CES-D, disabilities, and drugs/ treatments. High blood pressure omitted. Cells contain standard errors in parentheses. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale; AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

When both spouses are chronically ill, one spouse’s arthritis treatment is related to an initial increase in the other spouse’s depressive symptoms, regardless of gender (Models C and D). When both spouses are chronically ill, wife’s stroke treatment is related to a more rapid increase in husband’s depressive symptoms over time compared to if wife does not have stroke treatment (Model C), while husband’s stroke treatment is related to a greater initial level of wife’s depressive symptoms compared to if husband does not have stroke treatment (Model D). Husband’s diabetes treatment is related to a higher initial number of depressive symptoms for his wife, and husband’s lung disease treatment is related to a greater rate of increase in wife’s number of depressive symptoms over time compared to if the husband does not receive treatment for these conditions (Model D).

DISCUSSION

Extensive evidence shows the importance of marriage for health (Umberson et al. 2006, Waite and Gallagher 2000), and a separate body of work shows linkages between chronic conditions and depressive symptoms (Fiest et al. 2011; Taylor, McQuoid, and Rama Krishnan 2004). Despite these substantial literatures and the epidemiological reality that 80% of all adults over the age of 50 have at least one chronic condition (Anderson and Horvath 2004), little is known about how one spouse’s number of chronic conditions influences his or her spouse’s depressive symptoms and whether this depends on gender, health status of both spouses, and type of conditions. Because of the long duration of chronic conditions, the psychological consequences of these conditions reverberate and accumulate over time, yet most studies on this topic based on small, nonrepresentative samples of cross-sectional data, and dichotomous measures of chronic conditions (for overview, see Berg and Upchurch 2007). This current study advances our knowledge of how depressive symptoms are distributed within marriages and by particular health statuses, specifically, multimorbidity, in three key ways.

First, by looking at number of chronic conditions, rather than just treating the presence or absence of chronic conditions as dichotomous, this study demonstrates that more chronic conditions in one spouse are associated with more depressive symptoms in the other spouse. Furthermore, the growth curve models indicate not just that one spouse’s chronic conditions and the other spouse’s depressive symptoms are associated within time points and across time points but that, in some circumstances, changes in one spouse’s chronic conditions contribute to changes in the other spouse’s depressive symptoms. This indicates that the connection between one spouse’s multiple conditions and the other spouse’s mental health is a dynamic process, unfolding over time. The growth curve models suggest that the strains associated with a spouse’s chronic conditions (e.g., caregiving burden) build over time, both individually for each condition and additively as conditions accumulate. Few past studies examine multimorbidity, instead choosing samples in which only one spouse is ill and only one chronic condition (e.g., arthritis, breast cancer) is present (for overview, see Berg and Upchurch 2007). For most older couples, spouses are chronically ill with more than one chronic condition and more than one spouse is chronically ill, making it critical to understand the spousal mental health impact of multiple conditions (Freid et al. 2012).

Second, this study indicates that the association between number of chronic conditions and spousal depressive symptoms depends both on gender and on whether only one or both spouses have chronic conditions. The more conditions a husband has, the more depressed his wife is, both initially and over time, but only if both spouses are chronically ill. The relationship between one spouse’s chronic conditions is weaker when looking at wife’s number of conditions and husband’s depressive symptoms and occurs only over time. These findings support a recent study by Valle and colleagues (2013), which finds that a spouse’s chronic condition diagnosis impacts women’s mental health more than men’s. The strong and robust relationship between husband’s number of chronic conditions and wife’s depressive symptoms when both spouses are chronically ill has implications for wives’ physical health, as these wives’ mental health is worsened not only from their own chronic conditions but also from their husband’s.

One reason why chronically ill women are more depressed by their spouse’s chronic conditions than men are may be caregiving. As also suggested by other studies (Gove 1984; Thomeer et al. 2015), chronically ill wives with a chronically ill husband often still provide caregiving, likely overburdening them compared to women without chronic conditions married to a chronically ill husband or chronically ill husbands married to a chronically ill wife. A second reason in addition to caregiving involves empirical and theoretical understandings of how illness disrupts gender constructions in ways that increase depressive symptoms. Chronic conditions are found to be more depressing for men than for women due to masculine understandings of strength and virility contested by illness (Pudrovska 2010). Furthermore, studies conclude that depressive symptoms spread across spouses (Larson and Almeida 1999; Thomeer et al. 2013). Within a heterosexual marriage and understanding gender as relationally constructed, these studies together would suggest that a chronically ill man would be more negatively affected by his own illness than a chronically ill woman, and this would in turn spill onto his wife, perhaps especially if his wife is herself chronically ill.

Third, beyond multimorbidity, type of condition is also important in shaping the extent to which one spouse’s chronic conditions are related to the other spouse’s mental health. These associations further depend both on gender and on whether only one spouse or both spouses are chronically ill. The four key findings regarding type of condition involve diabetes, lung disease, arthritis, and stroke. Husband’s diabetes is correlated with an increase in wife’s depressive symptoms regardless of whether or not the wife is also chronically ill, but wife’s diabetes is not related to husband’s depressive symptoms. Diabetes often requires self-management, including health behavior changes, such as healthy diets and exercise, and vigilant and sustained adherence to a treatment regimen, such as taking insulin (Beverly, Miller, and Wray 2008), proving difficult and stressful (Beverly et al. 2008). Research finds that wives exert more effort into improving their spouse’s health behaviors than husbands (Reczek and Umberson 2012; Umberson 1992), which may explain why having a spouse with diabetes influences women more so than men. It may be that chronic conditions that require a high level of self-management, such as diabetes, are particularly impactful for wives rather than for men self-managing their own condition; men rely on their wives, whereas women with diabetes or other conditions that require self-management deal with it alone.

For arthritis, having a spouse with arthritis increases one’s own depressive symptoms only if one also has chronic conditions regardless of gender. Many studies have considered the negative mental health impact of having a spouse with arthritis (Bediako and Friend 2004; Martire et al. 2002), but these studies focus on women with arthritis and their husbands, not considering whether the husband also has arthritis and excluding couples in which both spouses have arthritis. Thus the experiences of men with arthritis are largely ignored, including when they are married to women with arthritis, and the experiences of women married to men with arthritis are similarly overlooked. Any conclusions about the importance of gender are conflated with patient or spouse role. These findings suggest that future studies considering arthritis should include the arthritic status of both spouses and consider husbands with arthritis as well as women.

Regarding stroke, a husband’s stroke increases his wife’s depressive symptoms initially (regardless of wife’s health status), but a wife’s stroke increases her husband’s depressive symptoms over time (only if the husband is also chronically ill). These gender differences may reflect differences in how stroke progresses for men and women and how wives adapt to having a spouse with stroke compared to husbands. Women married to a husband with stroke may need more mental health support early during the stroke, whereas men married to a wife with stroke may need more ongoing support even if they do not seem impacted earlier in the disease progression.

Each of these findings suggests the existence of complex, gendered, and condition-specific pathways that lead from chronic conditions to spouse’s depressive symptoms. These processes are relational, such that the health status of each spouse is important, and these pathways are likely shaped not by any individual chronic condition but by groupings of chronic conditions of each spouse. Sample sizes were too small to examine specific groupings of chronic conditions, but findings regarding number and type of condition suggest that this is an important future research topic.

Limitations and Future Research

Future research should continue to explore how one person’s physical health is linked to her or his spouse’s mental health, moving beyond the measures and focus of this study. First, this study focuses on depressive symptoms, but future studies should consider how chronic conditions influence spouses across an array of outcomes, including worry, anger, anxiety, substance use, physical health, and even stress-related biomarkers, like cortisol or blood pressure. Past studies indicate that women in general have higher CES-D scores than men (Kessler et al. 2005), and it may be that the mental health impact of having a spouse with chronic conditions is more reflected in women’s CES-D scores than men’s, whereas the mental health impact for men is reflected in different outcomes, like substance use or worry (Rosenfield et al. 2005). There may also be gender differences when comparing how chronic conditions impact a spouse’s physical compared to mental health. Valle and colleagues (2013) found that while a new incident of a chronic condition in spouses increases women’s CES-D score, it did not affect men’s CES-D score but did worsen men’s self-rated health.

A second limitation involves mortality and marital selection. This sample is limited to couples who are still married in later life; thus couples in which one spouse has died of a chronic condition and couples who have become divorced (perhaps because of chronic conditions) are excluded, perhaps contributing to an underestimation of results. Third, the potential mediating and moderating influence of marital quality is not considered due to data limitations. Past studies indicate that marital quality is a key dynamic in the association between one spouse’s chronic conditions and the other spouse’s depressive symptoms (Martire et al. 2010; Rohrbaugh et al. 2002). Caregiving, social control, or other forms of unpaid work—important points of focus for future studies especially when considering gender differences—are also not fully considered.

Fourth, this present study considers multimorbidity as measured by number and type of conditions, but future studies should incorporate number of conditions, type of conditions, severity of conditions, and timing and duration of conditions into a more comprehensive modeling of multimorbidity. This more comprehensive understanding of multimorbidity should also consider life course processes. The development of chronic conditions may be more or less depressing for spouses at certain points in the life course. This is especially relevant when considering multimorbidity and the chronic conditions of both spouses. If the diagnoses of multiple conditions occur within a short time frame, this may lead to more initial depressive symptoms than if the conditions are diagnosed over a lengthy period with time to adapt to each. Because self-reports likely represent an underrepresentation of actual disease prevalence within a population where those with low health care usage and mild symptoms are least likely to self-report conditions (Hayward 2002), future research should go beyond self-report and consider clinical measures of chronic conditions.

CONCLUSION

This study has important policy implications. In 2005, approximately 133 million Americans had a chronic condition, a number projected to steadily increase due to the rapid aging of the population, the greater life expectancies of people with chronic conditions, and the increase in disease-specific risk factors, like obesity (Anderson and Horvath 2004; Bodenheimer, Chen, and Bennett 2009). Thus this research has important policy implications for an aging population facing more and more chronic conditions. Many studies address what multimorbidity means for chronically ill people, but also critical is understanding what multimorbidity means for those in their social networks, most centrally, their spouse, and which spouses are most at risk for depressive symptoms. Taken collectively, the findings in this present study highlight the particular mental health vulnerabilities of spouses, especially chronically ill women who are married to men with multiple conditions with the greatest risk when husbands have arthritis, diabetes, lung disease, and/or stroke. While marriage has been understood as an important resource for the chronically ill (Revenson and DeLongis 2010), this study demonstrates the cost of chronic conditions for the spouse and that this cost is highest for chronically ill women married to chronically ill men. Previously designed couple-oriented interventions (for overview, see Martire et al. 2010) ignore gender and are designed for couples with only one spouse chronically ill and with only one condition. This study highlights the need to develop more carefully targeted interventions for couples with multiple conditions.

FUNDING

The author disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported in part by Grant 5 R24 HD042849, awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Biography

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Mieke Beth Thomeer is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Her research interests include aging, family, health, and gender. In her research, she addresses questions about how relationships influence and are influenced by physical and mental health, with particular attention to gender. She uses both qualitative and quantitative methods, with special emphasis on dyadic methods. Her research has been published in American Journal of Public Health, Journal of Marriage and Family, Journal of Gerontology, and other journals.

REFERENCES

- Anderson Gerard and Horvath Jane. 2004. “The Growing Burden of Chronic Disease in America.” Public Health Reports 119(3):263–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreson Elena M., Malmgren Judith A., Carter William B., and Patrick Donald L.. 1994. “Screening for Depression in Well Older Adults: Evaluation of a Short Form of the CES-D.” American Journal of Preventative Medicine 10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayotte Brian J., Yang Frances M., and Jones Richard N.. 2010. “Physical Health and Depression: A Dyadic Study of Chronic Health Conditions and Depressive Symptomatology in Older Adult Couples. Journals of Gerontology Series B 65B(4):438–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baider Lea and De-Nour A Kaplan. 1999. “Psychological Distress of Cancer Couples: A Levelling Effect.” New Trends in Experimental and Clinical Psychiatry 15(4):197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour Kamil E., Helmick Charles G., Theis Kristina A., Murphy Louise B., Hootman Jennifer M., Brady Teresa J., and Cheng Yileng J.. 2011. “Arthritis as a Potential Barrier to Physical Activity among Adults with Obesity: United States, 2007 and 2009.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(19):614–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett Karen, Mercer Stewart W., Norbury Michael, Watt Graham, Wyke Sally, and Guthrie Bruce. 2012. “Epidemiology of Multimorbidity and Implications for Health Care, Research, and Medical Education: A Cross-sectional Study.” Lancet 380(9836):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bediako Shawn M. and Friend Ronald. 2004. “Illness-specific and General Perceptions of Social Relationships in Adjustment to Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Role of Interpersonal Expectations.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 28(3):203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg Cynthia A. and Upchurch Renn. 2007. “A Developmental-contextual Model of Couples Coping with Chronic Illness Across the Adult Life Span.” Psychological Bulletin 133(6):920–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beverly Elizabeth A., Miller Carla K., and Wray Linda A.. 2008. “Spousal Support and Food-related Behavior Change in Middle-aged and Older Adults Living with Type 2 Diabetes.” Health Education & Behavior 35(5):707–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer Thomas, Chen Ellen, and Bennett Heather D.. 2009. “Confronting the Growing Burden of Chronic Disease: Can the U.S. Health Care Workforce Do the Job? Health Affairs 28(1):64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey Michelle A., Card Jeffrey W., Voltz James W., Arbes Samuel J. Jr., Germolec Dori R., Korach Kenneth S., and Zeldin Darryl C.. 2007. “It’s All about Sex: Gender, Lung Development and Lung Disease.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 18(8): 308–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case Anne and Paxson Christina. 2005. “Sex Differences in Morbidity and Mortality.” Demography 42(2):189–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emslie Carol, Hunt Kate, and Watt Graham. 2001. “Invisible Women? The Importance of Gender in Lay Beliefs about Heart Problems.” Sociology of Health & Illness 23(2):203–33. [Google Scholar]

- England Paula. 2005. “Emerging Theories of Care Work.” Annual Review of Sociology 31:381–99. [Google Scholar]

- Fiest Kirsten M., Currie Shawn R., Williams Jeanne V. A., and Wang JianLi. 2011. “Chronic Conditions and Major Depression in Community-dwelling Older Adults.” Journal of Affective Disorders 131(1–3): 172–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin Martin, Bravo Gina, Hudon Catherine, Lapointe Lise, Almirall José, Dubois Marie-France, and Vanasse Alain. 2006. “Relationship between Multimorbidity and Health-related Quality of Life of Patients in Primary Care.” Quality of Life Research 15(1):83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin Martin, Soubhi Hassan, Hudon Catherine, Bayliss Elizabeth A., and Marjan van den Akker. 2007. “Multimorbidity’s Many Challenges.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 334(7602):1016–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks Melissa M., Lucas Todd, Stephens Mary Ann Parris, Rook Karen S., and Gonzalez Richard. 2010. “Diabetes Distress and Depressive Symptoms: A Dyadic Investigation of Older Patients and Their Spouses.” Family Relations 59(5):599–610. [Google Scholar]

- Freid Virginia M., Bernstein Amy B., and Ann Bush Mary. 2012. “Multiple Chronic Conditions Among Adults Aged 45 and over: Trends over the Past 10 Years.” NCHS Data Brief No. 100. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George Linda K. and Lynch Scott M.. 2003. “Race Differences in Depressive Symptoms: A Dynamic Perspective on Stress Exposure and Vulnerability.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44(3):353–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn Liam G., Valderas Jose M., Healy Pamela, Burke Evelyn, Newell John, Gillespie Patrick, and Murphy Andrew W.. 2011. “The Prevalence of Multimorbidity in Primary Care and Its Effect on Health Care Utilization and Cost.” Family Practice 28(5):516–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldzweig Gil, Hubert Ayala, Walach Natalio, Brenner Baruch, Perry Shlomit, Andritsch Elisabeth, and Baider Lea. 2009. “Gender and Psychological Distress Among Middle- and Older-aged Colorectal Cancer Patients and Their Spouses: An Unexpected Outcome.” Critical Reviews in Oncology/ Hematology 70(1):71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gove Walter R. 1984. “Gender Differences in Mental and Physical Illness: The Effects of Fixed Roles and Nurturant Roles.” Social Science & Medicine 19(2):77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz Joseph G., Hovey Joseph P., Seligman Laura D., Arcury Thomas A., and Quandt Sara A.. 2006. “Evaluating Short-form Versions of the CES-D for Measuring Depressive Symptoms Among Immigrants from Mexico. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 28(3):404–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward Mark. 2002. Using the Health and Retirement Survey to Investigate Health Disparities. Retrieved March 16, 2014 (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/dmc/hrs_healthdisparities_hayward.pdf).

- Helgeson Vicki S., Snyder Pamela, and Seltman Howard. 2004. “Psychological and Physical Adjustment to Breast Cancer over 4 Years: Identifying Distinct Trajectories of Change.” Health Psychology 23(1):3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshaus Michael S. and Utz Rebecca L.. 2013. “Depressive Symptoms Following the Diagnosis of Major Chronic Illness.” Society and Mental Health 3(1):22–39. [Google Scholar]

- Juster, Thomas F and Suzman Richard. 1995. “An Overview of the Health and Retirement Study.” Journal of Human Resources 30:S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- Keles H, Ekici Arif B, Ekici Mehmet, Bulcun E, and Altinkaya V. 2006. “Effect of Chronic Diseases and Associated Psychological Distress on Health-related Quality of Life.” Internal Medicine Journal 37(1):6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny David A., Kashy Deborah A., and Cook William L.. 2006. Dyadic Data Analysis. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C., Berglund Patricia, Demler Olga, Jin Robert, Merikangas Kathleen R., and Walters Ellen E.. 2005. “Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.” JAMA Psychiatry 62(6):593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser Janice K. and Newton Tamara L.. 2001. “Marriage and Health: His and Hers.” Psychological Bulletin 127(4):472–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline Rex B. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- LaPlante Mitchell P. 2010. “The Classic Measure of Disability in Activities of Daily Living Is Biased by Age but an Expanded IADL/ADL Measure Is Not.” Journals of Gerontology Series B 65B(6):720–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson Reed W. and Almeida David M.. 1999. “Emotional Transmission in the Daily Lives of Families: A New Paradigm for Studying Family Process.” Journal of Marriage and Family 61(1):5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Marengoni Alessandra, Angleman Sara, Melis René, Mangialasche Francesca, Karp Anita, Garmen Annika, Meinow Bettina, and Fratiglioni Laura. 2011. “Aging with Multimorbidity: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Ageing Research Reviews 10(4):430–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire Lynn M., Stephens Mary Ann Parris, Druley Jennifer A, and Wojno William C. 2002. “Negative Reactions to Received Spousal Care: Predictors and Consequences of Miscarried Support.” Health Psychology 21(2):167–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire Lynn M., Schulz Richard, Helgeson Vicki S., Small Brent J., and Saghafi Ester M.. 2010. “Review and Meta-analysis of Couple-oriented Interventions for Chronic Illness.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 40(3):325–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John and Ross Catherine. 2003. Social Causes of Psychological Distress. New York: Aldine De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén Linda K. and Muthén Bengt O. 2010. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse Laurel, Mood Darlene, Templin Thomas, Mellon Suzanne, and George Tamara. 2000. “Couples’ Patterns of Adjustment to Colon Cancer.” Social Science & Medicine 50(2):271–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart Martin and Sorensen Silvia. 2006. “Gender Differences in Caregiver Stressors, Social Resources, and Health: An Updated Meta-analysis.” Journals of Gerontology Series B 61(1):P33–P45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pudrovska Tetyana. 2010. “Why Is Cancer More Depressing for Men than Women among Older White Adults?” Social Forces 89(2):535–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff Lenore Sawyer. 1977. “The CES-D Scale: A Self-report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population.” Applied Psychological Measurement 1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- RAND HRS Data [Data file]. 2010. Edited by Rand Center for the Study of Aging, Santa Monica, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Reczek Corinne and Umberson Debra. 2012. “Gender, Health Behavior, and Intimate Relationships: Lesbian, Gay, and Straight Contexts.” Social Science & Medicine 74(11):1783–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenson Tracey A. and Anita DeLongis. 2010. “Couples Coping with Chronic Illness.” Pp. 101–23 in Oxford Handbook of Coping and Health, edited by Folkman S. New York: Oxford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbaugh Michael J., Cranford James A., Shoham Varda, Nicklas John M., Sonnega John S., and Coyne James C.. 2002. “Couples Coping with Congestive Heart Failure: Role and Gender Differences in Psychological Distress.” Journal of Family Psychology 16(1):3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook Karen S., August Kristin J., Parris Stephens Mary Ann, and Franks Melissa M. 2011. “When Does Spousal Social Control Provoke Negative Reactions in the Context of Chronic Illness? The Pivotal Role of Patients’ Expectations.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 28(6): 772–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield Sarah, Lennon Mary Clare, and White Helene Raskin. 2005. “The Self and Mental Health: Self-salience and the Emergence of Internalizing and Externalizing Problems.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 46(4):323–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthig Joelle C., Trisko Jenna, and Stewart Tara L.. 2012. “The Impact of Spouse’s Health and Well-being on Own Well-being: A Dyadic Study of Older Married Couples.” Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology 31(5):508–29. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer Joseph L. and Graham John W.. 2002. “Missing Data: Our View of the State of the Art.” Psychological Methods 7(2):147–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel Michele J., Bradley Elizabeth H., Gallo William T., and Kasl Stanislav V.. 2004. “The Effect of Spousal Mental and Physical Health on Husbands’ and Wives’ Depressive Symptoms, among Older Adults.” Journal of Aging and Health 16(3):398–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor Warren D., McQuoid Douglas R, and Rama Krishnan K Ranga. 2004. “Medical Comorbidity in Late-life Depression.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychology 19(10):935–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomeer Mieke Beth, Reczek Corinne, and Umberson Debra. 2015. “Gendered Emotion Work Around Physical Health Problems in Mid- and Later-life Marriages.” Journal of Aging Studies 32:12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomeer Mieke Beth, Umberson Debra, and Pudrovska Tetyana. 2013. “Marital Processes around Depression: A Gendered and Relational Perspective.” Society and Mental Health 3(3):151–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra. 1992. “Gender, Marital Status, and the Social Control of Health Behavior.” Social Science & Medicine 34(8):907–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Chen Meichu D., House James S., Hopkins Kristine, and Slaten Ellen. 1996. “The Effect of Social Relationships on Psychological Well-being: Are Men and Women Really So Different?” American Sociological Review 61(5):837–57. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Thomeer Mieke Beth, and Lodge Amy C. 2015. “Intimacy and Emotion Work in Lesbian, Gay, and Heterosexual Relationships.” Journal of Marriage and Family 77(2):542–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Williams Kristi, Powers Daniel A., Liu Hui, and Needham Belinda. 2006. “You Make Me Sick: Marital Quality and Health over the Life Course.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 47(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle Giuseppina, Weeks Janet A., Taylor Miles G., and Eberstein Isaac W.. 2013. “Mental and Physical Health Consequences of Spousal Health Shocks among Older Adults.” Journal of Aging and Health 25(7):1121–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite Linda J. and Gallagher Maggie. 2000. The Case for Marriage: Why Married People Are Happier, Healthier, and Better Off Financially. New York: DoubleDay. [Google Scholar]

- Yee Jennifer L. and Schulz Richard. 2000. “Gender Differences in Psychiatric Morbidity among Family Caregivers.” Gerontologist 40(2):147–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]