Abstract

Embolectomy is one of the emergency procedures performed to remove emboli. Assessing the composition of human blood clots is an important diagnostic factor and could provide guidance for an appropriate treatment strategy for interventional physicians. Immunostaining has been used to identity compositions of clots as a gold-standard procedure, but it is time-consuming and cannot be performed in situ. Here, we proposed that the optical attenuation coefficient of optical coherence tomography (OCT) can be a reliable indicator as a new imaging modality to differentiate clot compositions. Fifteen human blood clots with multiple red blood cell (RBC) compositions from 21% to 95% were prepared using healthy human whole blood. A homogeneous gelatin phantom experiment and numerical simulation based on the Lambert-Beer’s law were examined to verify the validity of the attenuation coefficient estimation. The results displayed that optical attenuation coefficients were strongly correlated with RBC compositions. We reported that attenuation coefficients could be a promising biomarker to guide the choice of an appropriate interventional device in a clinical setting and assist in characterizing blood clots.

Keywords: Ischemic stroke, optical coherence tomography, optical attenuation coefficient, thrombus, mechanical thrombectomy, biomarker

1. Introduction

Ischemic stroke is a major cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide, accounting for approximately 27% of mortality and around 60% of stroke cases per year in the United States 1. It is an aetiologically heterogeneous disease, and proper treatment mandates timely investigation 2–4. Over the last decade, our knowledge of thromboembolus histology, mechanical properties and effects of these properties on the success of mechanical thrombectomy (MT) has grown significantly 5–9. Multiple randomized controlled trials have proven the efficacy and safety of MT in treating patients suffering from acute ischemic stroke (AIS) with large vessel occlusion 10, 11.

There is growing evidence supporting a relationship between selecting an appropriate device during MT (aspiration catheter versus stent-retriever device) and histological composition of clots 8, 12. The internal organization of ischemic stroke thrombi has been studied to guide the development of better recanalization strategies in stroke patients via MT for neurointerventionalists, and found that the RBC-rich stroke thrombi are more easily retrieved in comparison to fibrin-rich thrombi 9, 13. K. Maekawa et al. reported that using stent-based thrombectomy applying to the patients with erythrocyte-rich thrombi provided a shorter arrival-to-recanalization time interval and more favorable clinical outcomes 7. According to the stroke thromboembolism registry of imaging and pathology (STRIP) results, patients with red blood cell (RBC)-rich clots by using aspiration alone during MT were more likely to be completely revascularized than those with fibrin-rich clots 14. Therefore, evaluating compositions of thrombi are critical and can play a pivotal role in choosing an appropriate surgical device to increase success rate of MT and can also be useful for determining the etiology of these pathologies 15.

The histopathological evaluation of blood clots was carried out as early as 50 years ago in postmortem cases 16. In the most studies, the hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) stain or Martius Scarlet Blue (MSB) stain has been broadly used to characterize clot compositions as the gold standard 17, but extra reagents need to be prepared, the staining procedure is time consuming and it is subject to inter- and intra-observer variability as images are interpreted 18.

Noninvasive imaging modalities, such as non-contrast computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are commonly used imaging modalities, which can be applied, with some degree of accuracy, to characterize the histological composition of clots causing large vessel occlusion stroke 19. CT has been used for evaluating the correlation between thrombus attenuation and their histologic compositions in acute ischemic stroke (AIS), and it has been demonstrated that clot perviousness is associated with higher RBC compositions 15, 20, 21. On the other hand, the amount of RBCs within the thrombus also corresponds to the characterization of clots by the susceptibility vessel sign (SVS) in MRI 17, 19; however, SVS varies among MRI machines 17. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) has been used to indirectly quantify the compositions of clots by the level of permeability; however, extra contrast agents are required 22, 23.

Over the last two decades, optical coherence tomography (OCT) has been developed to investigate biological tissues and fluids due to ample advantages: non-invasive, non-contact, high spatial resolution, real-time measurement, no ionizing radiation, and high sensitivity to the topology of a surface 24–27. The optical attenuation coefficient in OCT is a reliable indicator to characterize various biological tissues such as arterial wall 28, 29, atherosclerotic plaques 30–32, enamel in teeth 33, 34, lymph nodes 35, 36, urothelial carcinoma in bladder 37, retinal nerve fiber layer 38, 39, human colon tissue 40, cerebral cortex 41, skin lesions 42, prostate tissue 43, breast tissue 44, and retinal microvascular 45. A previous research report noted that RBC-rich clots versus platelet-rich clots in the coronary arteries can be qualitatively distinguished simply by optical intensity as a threshold 46. However, using the optical attenuation coefficient in OCT to assess thrombus with various compositions has been rarely described. In this work, we reported that the optical attenuation coefficient in OCT is capable of evaluating clots with multiple RBC concentrations using human blood. The optical attenuation coefficient in OCT can be a promising biomarker for clot characterization and potentially implemented on catheters for real-time choosing an appropriate surgical device during MT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clot Analogue Preparation

Following Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval (16–001131) from Mayo Clinic in Rochester, healthy human whole blood was obtained from the blood transfusion service (BTS). Blood from one healthy donor (500 cc) was used. Blood was centrifuged at 1200 RPM for 20 minutes at 20°C which resulted in separation of blood into plasma, buffy-coat, and erythrocyte-rich layers. The plasma and erythrocytes (red blood cells, RBCs) were collected independently and then recombined in controlled ratios inside a 50 mL Falcon tube. We added 2.06% calcium chloride (Sigma Aldrich, Product No: C1016) and 2% thrombin (Sigma Aldrich, Product No: 10602400001) to facilitate the formation of clots. The solution inside each tube was mixed by 5 times inversion and then was quickly drawn into 3 ml syringes. Ten individual clots were made for five different groups with different RBC compositions (total 50 clots). In this study, three clots were randomly chosen from each group. The clots were taken out of the syringes and placed on a Petri dish with 100 mm diameter in air to image the samples with OCT. Analogues were prepared 4 hours before the experiment and they were stored at room temperature (26°C). For this study, five types of clot analogues were included with increasing concentrations of RBCs. Group 1: most fibrin-rich; Group 2: fibrin-rich; Group 3: mixed; Group 4: RBC-rich and Group 5: most RBC-rich. The clots were approximately cylindrically shaped though the diameter changed based on the RBC content. The reported RBC compositions were averaged from three clots of similar nominal RBC composition determined from the histological evaluation.

2.1. Histologic Analysis

Following our experiments, each clot analogue was fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin (Thermo-Scientific, Product No: 5701) for 2 days and then clot analogues were processed and embedded in paraffin. Formalin fixed paraffin embedded analogues were sectioned into 3 µm slices and then a representative slide of each analogue was stained with MSB. Histological quantification was performed using Orbit Image Analysis software (https://www.orbit.bio/, licensed under GPLv3) 47. The percentage of components including RBC and fibrin was determined (Table 1).

Table 1.

The RBC and fibrin compositions of the 15 clots by histological examinations.

| Clot Number | RBC Composition | Fibrin Composition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23.5% | 76.5% |

| 2 | 19.7% | 80.3% |

| 3 | 18.7% | 81.3% |

| 4 | 41.8% | 58.2% |

| 5 | 38.6% | 61.4% |

| 6 | 36.0% | 65.0% |

| 7 | 65.9% | 34.1% |

| 8 | 68.5% | 32.5% |

| 9 | 69.0% | 31.0% |

| 10 | 82.0% | 18.0% |

| 11 | 85.8% | 14.2% |

| 12 | 84.9% | 15.1% |

| 13 | 94.5% | 5.5% |

| 14 | 93.1% | 6.9% |

| 15 | 98.1% | 1.9% |

2.3. Fabrication of A Homogeneous Phantom

A 10% homogeneous gelatin phantom with 10 mm thickness was fabricated by using gelatin powder (gel strength 300 type A, G2500–1KG, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) mixed with 1 g titanium dioxide (TiO2) to provide optical scattering. A total volume of 100 mL of tap water in a 500 mL beaker was heated to 70 °C. The 10% v/v gelatin powder and 1 g TiO2 were added with stirring to the beaker for approximately 5 minutes to homogenize the solution. The mixed solution was placed in a de-gassing chamber to remove small bubbles in the fluid. After that, the mixed solution was poured into a regular Petri dish (85 mm × 10 mm) and placed in a 4 °C refrigerator for fast congealing.

2.4. Spectral-domain Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT) System

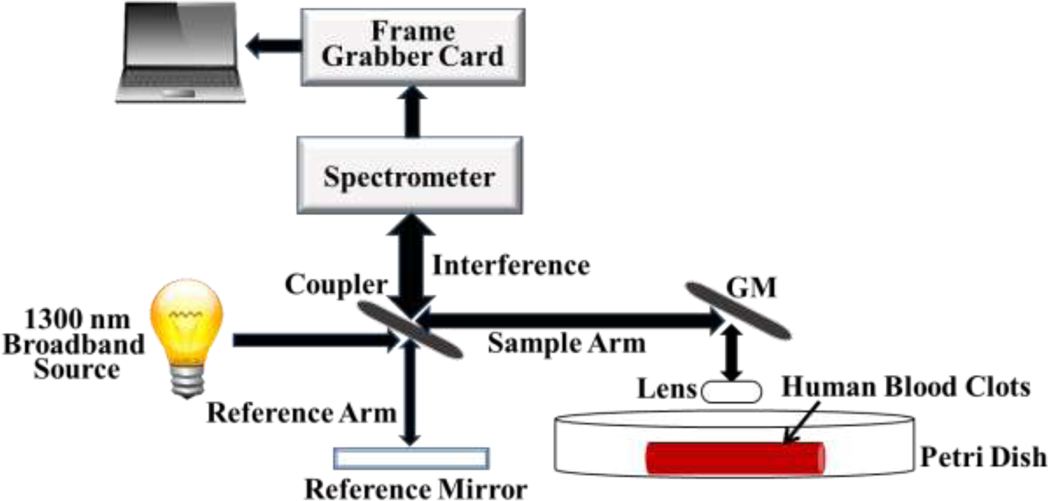

The optical layout of the spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) system is illustrated in figure 1. The low coherence broadband source is split into a reference beam directed toward a stationary reference mirror and a sample beam directed toward the human blood clots. The basic principle of OCT is based on the Michelson interferometer. The signals from clots and retroreflected light from the reference mirror are recombined by coupler. A spectral interferogram is formed by using spectrometers. A spectral domain OCT (SD-OCT) system (TEL320C1, Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA) is equipped with a 1300 nm source with low coherence broadband (236.8 nm of bandwidth) and LK3 lens kit (Thorlabs Inc., Newton, NJ, USA) to be able to produce 13 μm lateral resolution, 3.5 µm z-axis resolution and 3.6 mm of maximum imaging depth in air within 10 mm × 10 mm field of view (FOV) as the best ability, provided by Thorlabs Inc. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) is utilized to form an A-scan from the receiver array in the SD-OCT system. The customized 2D scan pattern with 100 µm scanning step (100 discrete points within 10 mm) in the lateral direction was developed to collect data. The customized acquisition was developed by using SpectralRadar software development kit (SDK) 4.4 Version provided by Thorlabs Inc. in Microsoft Visual C++ 2019 development environment (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). A 10 kHz A-scan rate was selected to obtain a better penetration depth in clots and 10 repeated measurements at the same location were performed for each individual clot in the study. For each measurement, the middle of the clots was aligned with the middle of the OCT field-of-view for images. The scan time is less than 1 second and data saving time is approximately 25 seconds. The average total time for 10 repeated measurements was around 4.5 mins for each clot.

Fig. 1.

The structure of SD-OCT system and the experimental set-up for evaluation of attenuation coefficients in human blood clots.

2.5. Attenuation Coefficient and Attenuation Distance Estimation

Various implementations of optical attenuation coefficient measurement have been proposed such as curve fitting methods 48, 49, depth-resolved methods 50, 51 and multiple-scattering methods 52. The attenuation coefficient is estimated by using curve fitting to OCT intensity depth profiles while samples are relatively uniform and homogenous, which assumes that attenuation coefficients are similar over a certain depth 50, 51, 53. The attenuation coefficient of the coherent light beam traveling through a homogeneous medium and back to the OCT detector is given by Lambert-Beer’s law and is expressed as

| (1) |

where I is the backscattered intensity collected by the detector, I0 is the intensity of the incident light beam, µ is the attenuation coefficient and the factor of 2 accounts for the round-trip of the light propagation 51, 53. In general, thrombi exhibit a homogeneous appearance 54, especially for acute thrombosis 55. For ischemic stroke thrombi, S. Staessens et al. studied the structural analysis of 188 nature clots after a thrombectomy procedure by using histological indications and reported that the RBC-rich ischemic stroke thrombi is composed of rather homogeneously distributed RBC that are densely packed and embedded in thin fibrin strands, with no other main structural components 9. Cines, et al., reported that analogous blood clots were formed uniformly and were isotropic in the internal network 56. Therefore, a curve fitting method is appropriate to evaluate attenuation coefficients of clot analogues with various RBC compositions.

Different fitting models influence the outcome of attenuation distances. Non-linear least squares curve-fitting is the most common approach to quantify optical properties from OCT images 57 and it has good flexibility to adapt to different data sets 58. Previous literature also reported that non-linear least squares fitting was adopted to quantify attenuation coefficients of weakly scattering media in OCT 48. In this study, a strong reflected signal, a peak in figure 2, from the surface of clots can be expected. While the peak was determined, a non-linear least squares curve fitting (quadratic polynomial) was performed to fit the OCT backscattered intensity signals on a decibel (dB) scale in the range between the peak signal and the signal at maximum depth (2.8 mm in this study). Figure 2 with red solid line indicates a curve fitting result as an example by using non-linear least squares to an A-scan signal in an RBC-rich clot. By utilizing this curve fitting, a specific depth dA-scan can be determined while the backscattered intensity of the OCT signal decays until it falls right below the noise floor (N.F.), and is given by

| (2) |

where I(d) in dB is the backscattered intensity of the OCT signal, dpeak is the depth that the maximum intensity of the OCT signal occurs on a fitting curve, d is OCT image at certain depth. The N.F. can be expressed as

| (3) |

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the methodology for estimating attenuation coefficient and attenuation distance estimation. N.F. stands for noise floor as defined in the area before the peak due to the surface reflection. The red curve is a quadratic polynomial fit to the data starting at dpeak_fit and is used to identify dA-scan where the intensity crosses the N.F.

The first term in the right side of equation was averaged reference signals in air and the second term means their standard deviation (SD). The N.F. was evaluated in air above the clot surface excluding the first 20 µm from the top of the image and 10 µm above the surface of the clot, which is the domain denoted to be Dair. Therefore, a single A-scan attenuation coefficient can be described by the following equation over the domain [dpeak, dA-scan]

| (4) |

where I(dpeak_fit) in dB is the OCT maximum intensity signal on a fitting curve, I(dA-scan) in dB is the OCT intensity signal on a fitting curve that reaches to N.F., and the denominator of Eq. (4) is defined as the attenuation distance. The physical meaning of the attenuation distance is the travel distance of photons that yield backscattered intensities that remain above the N.F. for a given acquisition. It should be noted that we relied on the backscattered signal from within the clots to make our determinations of attenuation distance. Additionally, even though Eq. (4) is linear after logarithmic transformation, we observed that the measured data had a nonlinear trend with distance (figure 2), so the nonlinear curve fitting of the measured data was used to determine the value of dA-scan.

Figure 2 illustrates the non-linear least squares curve fitting and the definitions from the Eqs. (2)–(4). Using this methodology for several A-lines, a mean attenuation distance dexp and attenuation coefficient µexp in an OCT clot image can be described by

| (5) |

| (6) |

where i is the number of the OCT A-line signal, and N is the total number of the A-line signals in each OCT clot image used for the calculation. In this study, we used N = 20 over a range from 3 mm to 7 mm with 0.2 mm spacing intervals for each OCT image. The comparison between phantom studies and numerical simulation results based on Lambert-Beer’s law were examined. The above procedure was programmed by using MATLAB R2019a software (Mathworks, Natick, MA) implemented in a desktop computer with Intel(R) Core (TM) i5–8500 CPU at 3 GHz processor, 8 GB memory and 64-bit Windows 10 operating system (Microsoft, Redmond, WA).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using by using GraphPad Prism Version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Two normality tests, the D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test and Shapiro-Wilk normality test, were used to evaluate whether the data can be assumed to be from normal distributions. In the study, data from the various RBC compositions did not pass the normality test, so non-parametric tests were selected. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) Kruskal-Wallis test was selected to examine the significant differences of dexp and μexp between different RBC compositions and Dunn’s adjustment was implemented for adjusting the p-values to account for the multiple testing among pairs of groups with different RBC compositions. The results of the phantom study were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) as that data passed the normality test. As the experimental data was not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were used for analysis, all the statistical results are presented as the median (interquartile range, IQR). The Spearman correlation test was used to examine the correlation between RBC compositions and estimates of dexp and μexp. The significant differences were considered when the p-value was < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

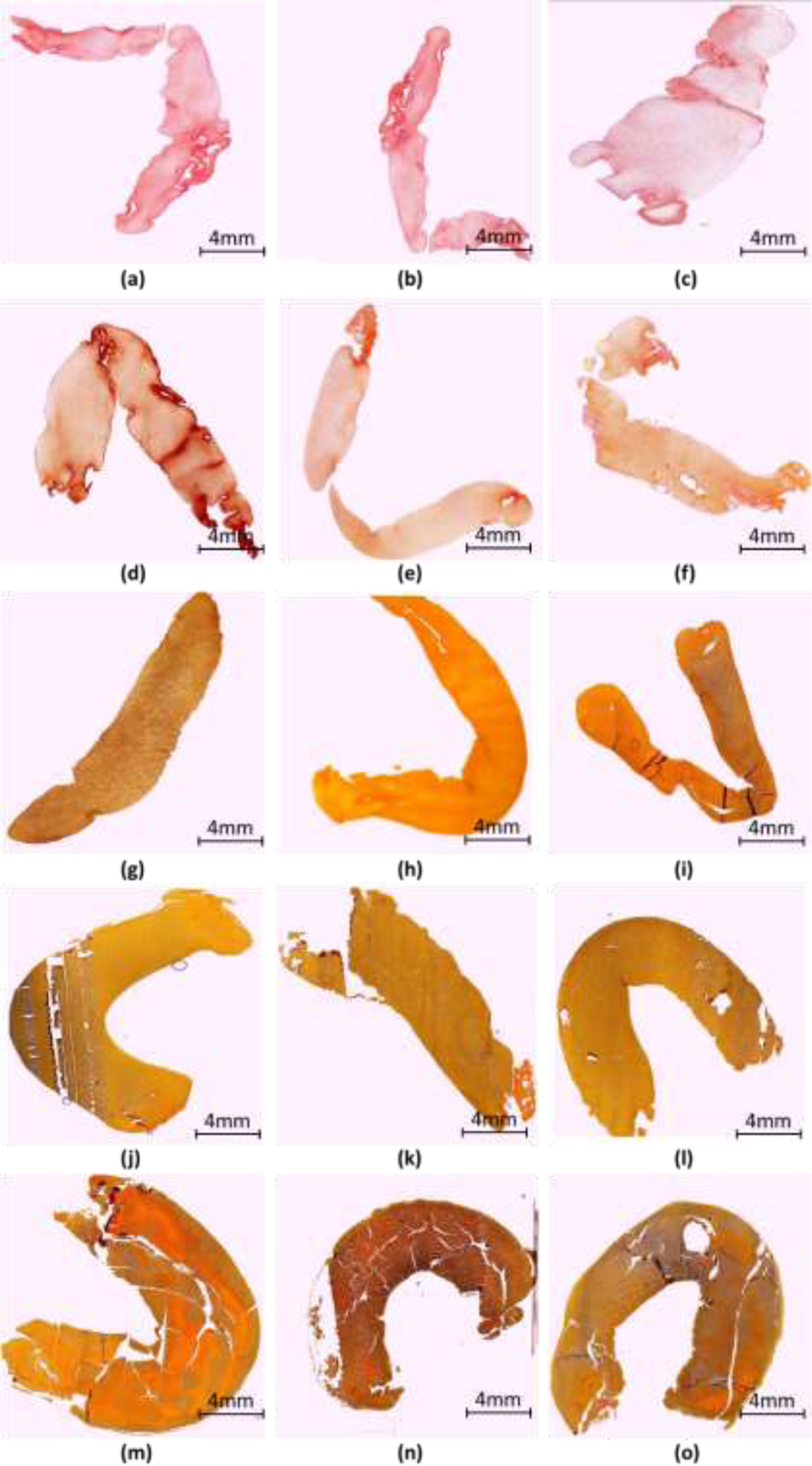

The human clot analogues used in this study are optimized to reflect the varying histological compositions of clots retrieved from acute ischemic stroke patients. The volume of RBCs and plasma added to each clot is optimized based on clotting mechanisms. During the clotting process, fibrinogen converts to fibrin, trapping the cellular elements of blood including RBCs. As the concentration of fibrin increases with increasing plasma content, clots contract to greater degree. The function of clot contraction is to reinforce hemostasis by forming a seal, promote wound healing by approximating the edges, and restore blood flow by decreasing the area obstructed by intravascular clots 56. The serum, devoid of cells and fibrinogen, is extruded from the clot as clot contraction occurs and RBC are tightly packed taking on a polyhedral shape. To determine actual RBC composition, the histological evaluation was performed on each individual clot after the OCT images was captured. The histological images of all the clots are shown in figure 3. The histological images indicate that the clots are fairly homogeneous and did not show appreciable changes through the thickness of the clot. For each nominal mixture of RBC:fibrin, the mean value of the RBC content was measured. The actual RBC compositions of approximate 21%, 39%, 68%, 84% and 95% versus their fibrin compositions were determined from the histological evaluation (Table 1). Based upon clinical experience, the RBC composition of clots extracted using MT ranges from approximate 5% to 85% RBC compositions; therefore, the ranges of the RBC compositions in the study are appropriate to cover the range of the clinical cases.

Fig. 3.

Illustration of the histological examination for the RBC compositions of all clots. (a-c) 21% RBC, (d-f) 39% RBC, (g-i) 68% RBC, (j-l) 84% RBC and (m-o) 95% RBC. The scale bar represents 4 mm.

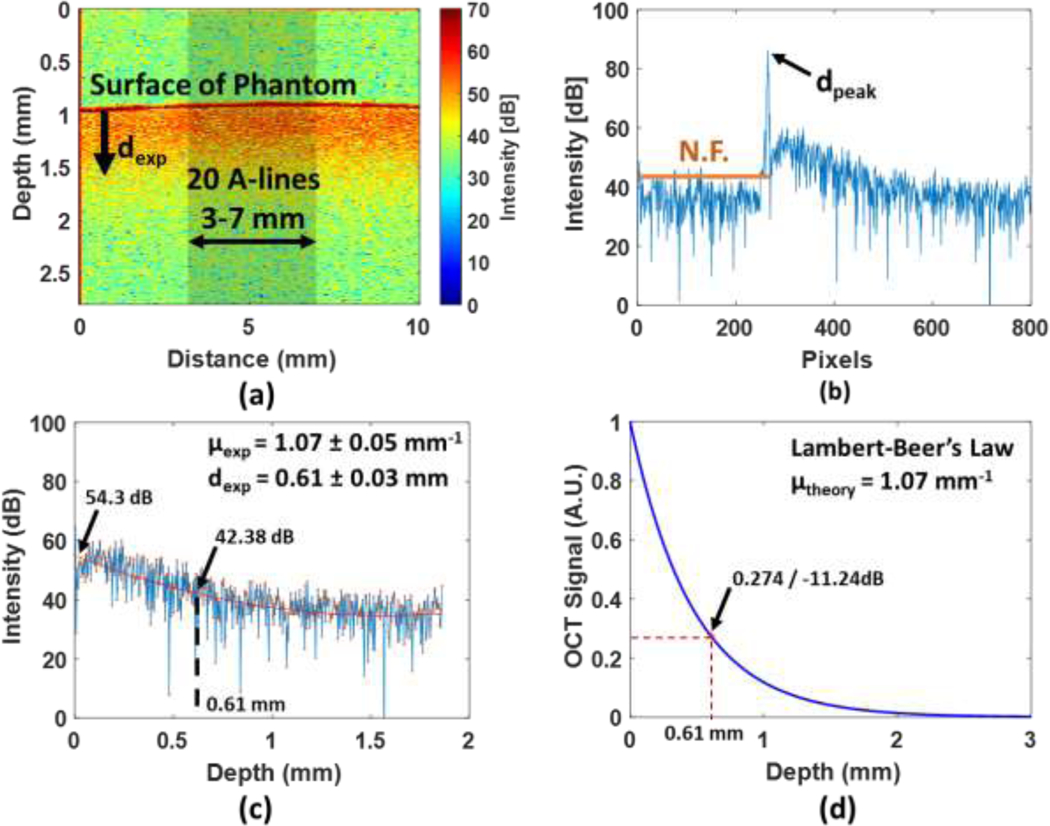

A 10% homogeneous gelatin phantom experiment and numerical simulation were used to verify the validity of the attenuation coefficient estimation. The penetration depth dexp of the homogeneous phantom is clearly observed via an OCT image presented in figure 4(a). In figure 4(b), the waveform in blue indicates an example of averaged 20 A-scan signals from a lateral range from 3 mm to 7 mm (the shadow portion in figure 4(a) with 0.2 mm interval in x-axis. The reason that we examined the 4 mm range of the clots is to obtain consistent results. As a test, different lateral ranges of A-lines were analyzed in the phantom study, and we reported that the attenuation coefficients and attenuation distances are highly consistent (Table 2). After performing the curve fitting to 20 individual A-scan log-scaled signals by using a quadratic polynomial method, the mean attenuation coefficient µexp and mean attenuation distance dexp of the homogeneous phantom were found to be 1.07 ± 0.05 mm−1 and 0.61 ± 0.03 mm, respectively. Based on these results, the OCT intensity decay was approximately 11.92 dB (54.3 – 42.38 dB) as presented in figure 4(c). According to the Lambert-Beer’s law presented in Eq. 1, the result of the numerical simulation by setting 1.07 mm−1 of the attenuation coefficient is shown in the figure 4(d). Checking the curve at the depth of 0.61 mm, the OCT intensity change was obtained as 0.274 A.U., which is −11.24 dB (20*log100.274). The phantom experimental result exhibited a good agreement with our numerical simulation result.

Fig. 4.

A homogeneous phantom testing and a numerical simulation with finite depth. (a) shows the OCT image of a homogeneous phantom. (b) represents an example of averaged 20 A-scan signals (the waveform in blue) and the N.F. (the solid line in orange). (c) The quadratic polynomial curve fitting (red line) was used to fit 20 individual A-scan signals. (d) A result from the numerical simulation based on Lambert-Beer’s Law.

Table 2.

The phantom study with different sizes of the examined ranges for evaluating the mean attenuation distances (dA-scan) and mean attenuation coefficients (µ) with SD.

| Examined Ranges in Phantom |

dA-scan (mm) ±SD |

µ (mm−1) ±SD |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1, 40 A-lines (3 to 5 mm with 0.1 mm interval) | 0.613 ± 0.038 | 1.053 ± 0.062 |

| Case 2, 20 A-lines (3 to 5 mm with 0.2 mm interval) | 0.605 ± 0.032 | 1.069 ± 0.055 |

| Case 3, 40 A-lines (1 to 9 mm with 0.2 mm interval) | 0.608 ± 0.034 | 1.059 ± 0.059 |

| Case 4, 80 A-lines (1 to 9 mm with 0.1 mm interval) | 0.610 ± 0.038 | 1.054 ± 0.061 |

The OCT clot images with 21%, 39% and 95% RBC composition are presented in figures 5(a-c). In the 21% RBC composition (fibrin-rich) in figure 5(a), a shallow penetration can be observed due to sparse scatterers inside the clot. U. Sharma et al. noted that it becomes difficult to obtain meaningful structural information if there are sparse scatterers 59, which is the case for fibrin-rich (or RBC-poor) clots. Noticeably, fewer scatterers allow a deeper penetration depth but less meaningful structural information inside samples. In the study, “a shallow penetration depth” or “a shorter attenuation distance” can be interpreted as “more difficult to achieve meaningful structural information” in the study because fibrin-rich clots, specifically the 21% RBC composition clots, are semi-transparent. As noted above, our measurements of attenuation coefficient and attenuation distance are based on the backscattered signal, so a lack of scattering in the fibrin-rich clots yields a low attenuation distance as the signal returns to the noise floor quickly, and the attenuation coefficient is considered high due to this short distance. On the contrary, a clear penetration depth in the 95% RBC composition (RBC-rich) is recognized in figure 5(c) because of ample scatterers inside the clot. The non-linear least squares curve fitting quantitatively expresses the optical attenuation with the exponential decay for three different RBC compositions, presented in figure 5(d). The backscattered intensity signal in RBC-rich clots is better defined than that in fibrin-rich clots because of the contributions of considerable RBCs as scatterers.

Fig. 5.

The examples represent optical penetration depths on human blood clots with three different RBC composition: (a) 21%, (b) 39% and (c) 95% RBC composition. (d) exhibits the quantitative attenuation in clots by curve fitting with different slopes.

The median attenuation distance and median attenuation coefficient of each individual clot with IQRs are illustrated in figure 6, respectively. The results demonstrated that attenuation distance and attenuation coefficient of human bold clots were strongly associated with RBC compositions. The range of median attenuation distance with IQR is from 0.23 (0.05) mm to 0.31 (0.07) mm in 21%, from 0.27 (0.06) mm to 0.56 (0.05) mm in 39%, from 0.45 (0.04) mm to 0.52 (0.04) mm in 68%, from 0.47 (0.10) mm to 0.57 (0.05) mm in 84%, and from 0.64 (0.03) mm to 0.71 (0.04) mm in 95% RBC composition. The range of median attenuation coefficient with IQR is from 1.96 (0.40) mm−1 to 2.43 (0.45) mm−1 in 21%, from 1.06 (0.07) mm−1 to 2.06 (0.53) mm−1 in 39%, from 1.18 (0.09) mm−1 to 1.30 (0.12) mm−1 in 68%, from 1.05 (0.07) mm−1 to 1.27 (0.26) mm−1 in 84%, and from 0.87 (0.04) mm−1 to 0.98 (0.04) mm−1 in 95% RBC composition. As RBC composition increased, the results showed a decreasing trend in median attenuation coefficients.

Fig. 6.

The median attenuation distance (top row) and median attenuation coefficient (bottom row) with their IQRs on each individual clot. Three clots in each RBC composition were collected, 10 images were captured in each colt by OCT and 20 A-scan signals were measured in each OCT image. The abbreviation of Att Dist, Att Coe in y-axis represent attenuation distance and attenuation coefficient, respectively.

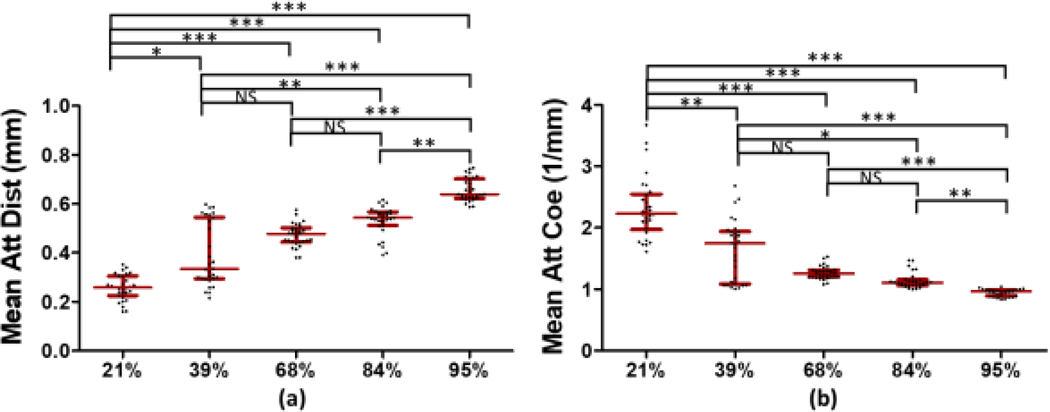

The results for the three individual clots in each RBC concentrations were pooled for statistical analysis, and the results are illustrated in figure 7 by using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s adjustment for multiple comparisons. The statistically significant difference with the p-value less than 0.05 was also presented in any two-group comparison. The median attenuation distance with its IQR is 0.26 (0.08) mm in 21%, 0.33 (0.25) mm in 39%, 0.48 (0.06) mm in 68%, 0.54 (0.05) mm in 84% and 0.64 (0.08) mm in 95% RBC composition, presented in figure 7(a). The results clearly showed a strong positive correlation between the mean attenuation distances the RBC compositions in clots. Multiple comparisons expressed the statistically significant difference with the p-value less than 0.05. We noticed that the 39%−68% and 68%−84% comparisons displayed a non-significant difference with the p-value larger than 0.05 due to clot #4 and clot #12 in figure 6 to increase the deviation. More clots will need be collected to reduce the deviation in the future study. However, entire trend clearly demonstrated a strong positive relationship between attenuation distances and RBC compositions in clots.

Fig. 7.

Three samples in each RBC composition were incorporated into one large group. (a) indicates the median attenuation distance with their IQRs and (b) shows the median attenuation coefficient with their IQRs. The abbreviation of Att, Dist and Coe in y-axis represent attenuation, distance and coefficient, respectively, and the symbols *, ** and *** indicate the p-value < 0.05 and < 0.01 and < 0.001, respectively. The abbreviation of NS means non-significant.

The median attenuation coefficient with its IQR is 2.23 (0.58) mm−1 in 21%, 1.74 (0.85) mm−1 in 39%, 1.26 (0.11) mm−1 in 68%, 1.11 (0.09) mm−1 in 84% and 0.96 (0.10) mm−1 in 95% RBC composition, presented in figure 7(b). As RBC composition increased, the median attenuation coefficient was significantly decreased. A similar result was found in coronary arterial RBC-rich clots which could be distinguished from platelet-rich clots by using the 50% OCT intensity as an criteria 46. Differentiating clots with various RBC compositions has been not widely studied. In the study the clots with multiple RBC compositions were demonstrated to be able to distinguish by computer-aided quantification.

The variability of the attenuation coefficients in fibrin-rich clots are greater than in RBC-rich clots (Fig. 6 and 7), which could be due to insufficient scatterers and the variations of the fibrin network in clots. With the RBC-rich clots, there is much more signal to be utilized for the estimation and more consistency within the clots due to the higher level of optical scatterers. For the fibrin-rich clots, there are fewer scatterers so the attenuation measurements have more variability. The other reason could be due to the variations of the fibrin network in clots. The fibrin network in fibrin-rich clots is denser than it in RBC-rich clots. During the coagulation process, water was absorbed by the formed fibrin network and was stored within the swollen fibrin. Once the clots were pulled from the syringe during the experiments, the water in fibrin network starts to weep from each phenotype clot in different ways with respect to time 60. Each fibrin network in clots is independent, and the rate of water extracting from the fibrin network could be different. In addition, gravity and experimental handling could squeeze water out from the fibrin network, and some water was naturally lost due to vaporization when exposed to ambient conditions. These phenomena could increase the deviation in the fibrin-rich clot cases, a possible outlier case such as the clot #4, and the variation of the deviation of clot #4 compared to clot #5 and 6 in the study. More samples in each RBC composition will be needed to examine in future works.

Attenuation is the sum of effects due to scattering and absorption. For these clots, the absorption properties should not largely affect the measurement of the total attenuation coefficient. M. Friebel et al. investigated optical parameters of blood cells using an integrating sphere spectrometer in the spectral range of 250 to 2000 nm and reported the absorption of hemoglobin tends to be negligible as the investigated wavelength range includes the spectral region above 1100 nm 61. I. Fredriksson et al. reported the absorption spectra of hemoglobin with concentration relevant for normal blood and solid phantoms with high concentration hemoglobin phantom. The maximum absorption coefficients of both normal blood and solid phantoms are located in the wavelength interval 500 to 600 nm and very close to zero above 800 nm 62. Our SD-OCT system is equipped with a 1300 nm source; therefore, the absorption properties of RBCs at the chosen wavelength should contribute little to the measurement of the total attenuation coefficient.

The axial point-spread function (PSF) of the OCT system must be taken into account for evaluating attenuation coefficients. In clinical catheter-based OCT, the distance between targets and lens are always changing but dynamic focusing is not possible. Therefore, the axial PSF is important 48, 50, 53. In our experiments, we tried to minimize effects of the PSF by keeping the distance between the surface of the samples and the lens a constant value (e.g., the sample surface was kept at z = 1 mm in the imaging window) as a fixed focus (Please see Fig. 4a and Figs. 5a-c), so that the images have similar baselines. We positioned the OCT lens to be perpendicular to the clot’s surface. Using the fixed focus approach is an appropriate method for this pilot study to investigate clot compositions. In the study, we have demonstrated that OCT attenuation is a promising indicator to differentiate clot compositions. We will translate this method into catheter-based OCT with confocal property for real-time clot evaluation during mechanical thrombectomy (MT) procedures.

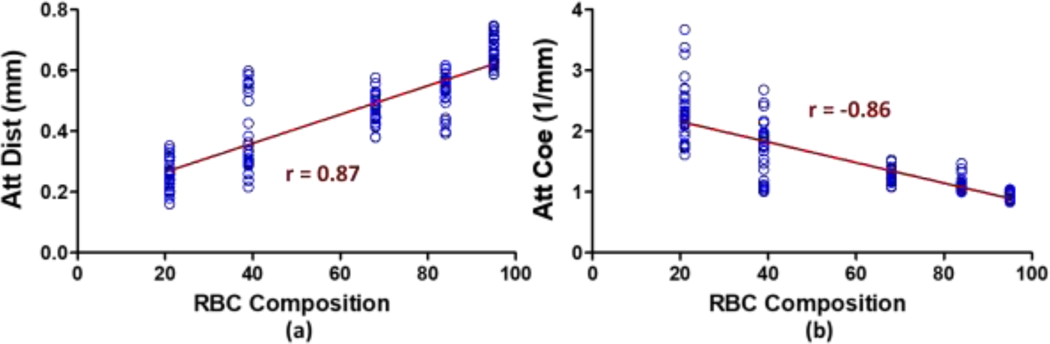

We also evaluated the correlation coefficient by using Spearman correlation coefficient. The correlation coefficient r was 0.87 between attenuation distances and RBC compositions presented in figure 8(a) and was −0.86 between attenuation coefficient and RBC compositions displayed in figure 8(b). Both correlations were statistically significant with the p < 0.0001. The study demonstrated that optical attenuation coefficients were strongly associated with levels of RBC compositions in human blood clots and were capable of discriminating various RBC compositions of clots. Noticeably, thrombi could be homogenous when there is a high percentage of one component, acute clots or RBC-based, and could be heterogeneous if clots are fibrin-based or chronic clots 9, 54, 55. Therefore, clots retrieved from patients could vary in composition from proximal to distal portions. Reducing the variables to explore a mechanical mechanism is essential as the first step 63. A second step would be to assess the heterogeneity of clots with a localized attenuation algorithm, which will be undertaken in a future study. This data provides a basis for further investigation of additional clots of additional compositions to determine our discrimination precision. Additional validation will be necessary with intravascular OCT systems to determine the level of discrimination that could be achieved in a more realistic setting for future translation of this methodology. Using the attenuation coefficient or attenuation distance could assist in determining the clot composition and assisting in choosing an appropriate approach form embolectomy procedures.

Fig. 8.

The correlation coefficient r between (a) RBC composition and attenuation distance and (b) RBC composition and attenuation coefficient are illustrated by using Spearman correlation coefficient and demonstrated the significant correlation with p < 0.0001.

4. Conclusion

Fifteen individual blood clots were fabricated using healthy human whole blood and imaged with OCT. The optical attenuation coefficient and attenuation distance were determined by using a non-linear least squares (quadratic polynomial) curve fitting approach. A numerical simulation for attenuation estimation had good agreement with a gelatin phantom experiment. We concluded that the optical attenuation coefficients and attenuation distances were significantly correlated with RBC compositions. The attenuation coefficient in fibrin-rich clots were much higher than those in RBC-rich clots. This study demonstrated that optical attenuation coefficients in OCT would be a promising indictor to assess clot compositions, to provide a suitable treatment strategy in the clinical setting and to assist clinical experts for diagnosing human blood clot pathology. In future studies, more clots with various compositions will need to be involved. A feedback mechanism of optical attenuation coefficient measurement will be considered with intravascular OCT for analyzing clot compositions and providing an appropriate selection of surgical devices during in vivo embolectomy in real-time.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs. Jennifer L. Poston for administrative assistance.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS105853). The content is solely the responsibility of authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Declarations:

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this article.

Ethics Approval

The institutional review boards (IRB) from Mayo Clinic in Rochester approved the study protocol (16–001131).

Availability of Data and Material

The healthy human whole blood was obtained from the blood transfusion service (BTS).

References

- [1].Das S, Chandra Ghosh K, Malhotra M, Yadav U, Sankar Kundu S, Kumar Gangopadhyay P Ann Neurosci 2012, 19, 61–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Montaner J, Perea-Gainza M, Delgado P, Ribo M, Chacon P, Rosell A, Quintana M, Palacios ME, Molina CA, Alvarez-Sabin J Stroke 2008, 39, 2280–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Donnan GA, Fisher M, Macleod M, Davis SM Lancet 2008, 371, 1612–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Grau AJ, Weimar C, Buggle F, Heinrich A, Goertler M, Neumaier S, Glahn J, Brandt T, Hacke W, Diener HC Stroke 2001, 32, 2559–2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hashimoto T, Hayakawa M, Funatsu N, Yamagami H, Satow T, Takahashi JC, Nagatsuka K, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Kira JI, Toyoda K Stroke 2016, 47, 3035–3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Undas A, Slowik A, Wolkow P, Szczudlik A, Tracz W Thromb Res 2010, 125, 357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Maekawa K, Shibata M, Nakajima H, Mizutani A, Kitano Y, Seguchi M, Yamasaki M, Kobayashi K, Sano T, Mori G, Yabana T, Naito Y, Shimizu S, Miya F Cerebrovasc Dis Extr 2018, 8, 39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Xu RG, Ariens RAS Haematologica 2020, 105, 257–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Staessens S, Denorme F, Francois O, Desender L, Dewaele T, Vanacker P, Deckmyn H, Vanhoorelbeke K, Andersson T, De Meyer SF Haematologica 2020, 105, 498–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, Dippel DW, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, Davalos A, Majoie CB, van der Lugt A, de Miquel MA, Donnan GA, Roos YB, Bonafe A, Jahan R, Diener HC, van den Berg LA, Levy EI, Berkhemer OA, Pereira VM, Rempel J, Millan M, Davis SM, Roy D, Thornton J, Roman LS, Ribo M, Beumer D, Stouch B, Brown S, Campbell BC, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Saver JL, Hill MD, Jovin TG, collaborators H Lancet 2016, 387, 1723–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, Coffey CS, Hoh BL, Jauch EC, Johnston KC, Johnston SC, Khalessi AA, Kidwell CS, Meschia JF, Ovbiagele B, Yavagal DR, C. American Heart Association Stroke Stroke 2015, 46, 3020–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Raychev R, Saver JL Neurol Clin Pract 2012, 2, 231–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ducroux C, Di Meglio L, Loyau S, Delbosc S, Boisseau W, Deschildre C, Ben Maacha M, Blanc R, Redjem H, Ciccio G, Smajda S, Fahed R, Michel JB, Piotin M, Salomon L, Mazighi M, Ho-Tin-Noe B, Desilles JP Stroke 2018, 49, 754–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Brinjikji W, Fitzgerald S, Kallmes DF, Layton K, Hanel R, Pereira VM, Kvamme P, Delgado J, Yoo A, Jahromi B, Almekhlafi M, Gounis M, Nogueira RG Stroke 2020, 51, A147–A147. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Benson JC, Fitzgerald ST, Kadirvel R, Johnson C, Dai D, Karen D, Kallmes DF, Brinjikji W J Neurointerv Surg 2020, 12, 38–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Torvik A, Joergensen L J Neurol Sci 1964, 1, 24–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fitzgerald S, Mereuta OM, Doyle KM, Dai D, Kadirvel R, Kallmes DF, Brinjikji W J Neurosurg Sci 2019, 63, 292–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jorgensen AS, Rasmussen AM, Andersen NKM, Andersen SK, Emborg J, Roge R, Ostergaard LR Cytom Part A 2017, 91a, 785–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liebeskind DS, Sanossian N, Yong WH, Starkman S, Tsang MP, Moya AL, Zheng DD, Abolian AM, Kim D, Ali LK, Shah SH, Towfighi A, Ovbiagele B, Kidwell CS, Tateshima S, Jahan R, Duckwiler GR, Vinuela F, Salamon N, Villablanca JP, Vinters HV, Marder VJ, Saver JL Stroke 2011, 42, 1237–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sporns PB, Hanning U, Schwindt W, Velasco A, Buerke B, Cnyrim C, Minnerup J, Heindel W, Jeibmann A, Niederstadt T Cerebrovasc Dis 2017, 44, 344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mori H, Hayashi K, Uetani M, Matsuoka Y, Iwao M, Maeda H Radiology 1987, 163, 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Borggrefe J, Kottlors J, Mirza M, Neuhaus VF, Abdullayev N, Maus V, Kabbasch C, Maintz D, Mpotsaris A Clin Neuroradiol 2018, 28, 515–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bittencourt MS, Achenbach S, Marwan M, Seltmann M, Muschiol G, Ropers D, Daniel WG, Pflederer T J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2012, 6, 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wang S, Larin KV Journal of biophotonics 2015, 8, 279–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Razani M, Mariampillai A, Sun CR, Luk TWH, Yang VXD, Kolios MC Biomedical Optics Express 2012, 3, 972–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Liu HC, Kijanka P, Urban MW Biomed Opt Express 2020, 11, 1092–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu HC, Kijanka P, Urban MW Journal of biophotonics 2020, 13, e201960134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Schmitt JM, Knuttel A, Yadlowsky M, Eckhaus MA Phys Med Biol 1994, 39, 1705–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Popescu DP, Flueraru C, Mao Y, Chang S, Sowa MG Biomed Opt Express 2010, 1, 268–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].van der Meer FJ, Faber DJ, Baraznji Sassoon DM, Aalders MC, Pasterkamp G, van TG Leeuwen IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2005, 24, 1369–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Xu C, Schmitt JM, Carlier SG, Virmani R J Biomed Opt 2008, 13, 034003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Liu S, Sotomi Y, Eggermont J, Nakazawa G, Torii S, Ijichi T, Onuma Y, Serruys PW, Lelieveldt BPF, Dijkstra J J Biomed Opt 2017, 22, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Popescu DP, Sowa MG, Hewko MD, Choo-Smith LP J Biomed Opt 2008, 13, 054053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hariri I, Sadr A, Shimada Y, Tagami J, Sumi Y J Dent 2012, 40, 387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].McLaughlin RA, Scolaro L, Robbins P, Saunders C, Jacques SL, Sampson DD Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv 2009, 12, 657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Scolaro L, McLaughlin RA, Klyen BR, Wood BA, Robbins PD, Saunders CM, Jacques SL, Sampson DD Biomed Opt Express 2012, 3, 366–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cauberg EC, de Bruin DM, Faber DJ, de Reijke TM, Visser M, de la Rosette JJ, van Leeuwen TG J Biomed Opt 2010, 15, 066013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].van der Schoot J, Vermeer KA, de Boer JF, Lemij HG Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012, 53, 2424–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kjellstrom U, Andreasson S, Ponjavic V Acta Ophthalmol 2014, 92, 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zhao Q, Zhou C, Wei H, He Y, Chai X, Ren Q J Biomed Opt 2012, 17, 105004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rodriguez CL, Szu JI, Eberle MM, Wang Y, Hsu MS, Binder DK, Park BH Neurophotonics 2014, 1, 025004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Goulart VP, dos Santos MO, Latrive A, Freitas AZ, Correa L, Zezell DM J Biomed Opt 2015, 20, 051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Swaan A, Muller BG, Wilk LS, Almasian M, van Kollenburg RAA, Zwartkruis E, Rozendaal LR, de Bruin DM, Faber DJ, van Leeuwen TG, van Herk MB J Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201800274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Foo KY, Chin L, Zilkens R, Lakhiani DD, Fang Q, Sanderson R, Dessauvagie BF, Latham B, McLaren S, Saunders CM, Kennedy BF J Biophotonics 2020, e201960201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wu J, Zhang X, Azhati G, Li T, Xu G, Liu F Acta Ophthalmol 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kume T, Akasaka T, Kawamoto T, Ogasawara Y, Watanabe N, Toyota E, Neishi Y, Sukmawan R, Sadahira Y, Yoshida K Am J Cardiol 2006, 97, 1713–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Fitzgerald S, Wang SL, Dai DY, Murphree DH, Pandit A, Douglas A, Rizvi A, Kadirvel R, Gilvarry M, McCarthy R, Stritt M, Gounis MJ, Brinjikji W, Kallmes DF, Doyle KM Plos One 2019, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Faber D, van der Meer F, Aalders M, van Leeuwen T Opt Express 2004, 12, 4353–4365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].van Soest G, Goderie T, Regar E, Koljenovic S, van Leenders GL, Gonzalo N, van Noorden S, Okamura T, Bouma BE, Tearney GJ, Oosterhuis JW, Serruys PW, van der Steen AF J Biomed Opt 2010, 15, 011105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Liu J, Ding N, Yu Y, Yuan X, Luo S, Luan J, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Ma Z J Biomed Opt 2019, 24, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Vermeer KA, Mo J, Weda JJ, Lemij HG, de Boer JF Biomed Opt Express 2013, 5, 322–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Almasian M, Bosschaart N, van Leeuwen TG, Faber DJ J Biomed Opt 2015, 20, 121314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Chang S, Bowden AK J Biomed Opt 2019, 24, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Brosnan RB in Chapter 8 - Utilization of Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetic Resonance Angiography for Cardiac Thrombus, Vol. (Ed. Topaz O), Academic Press, 2018, pp.115–121. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Khosa F, Otero HJ, Prevedello LM, Rybicki FJ, Di Salvo DN AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010, 194, 1099–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Cines DB, Lebedeva T, Nagaswami C, Hayes V, Massefski W, Litvinov RI, Rauova L, Lowery TJ, Weisel JW Blood 2014, 123, 1596–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Almasian M, University of Amsterdam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Austin PC, Park-Wyllie LY, Juurlink DN Pharmacoepidem Dr S 2014, 23, 819–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Sharma U, Chang EW, Yun SH Optics Express 2008, 16, 19712–19723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Johnson S, Chueh J, Gounis MJ, McCarthy R, McGarry JP, McHugh PE, Gilvarry M J Neurointerv Surg 2020, 12, 853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Friebel M, Helfmann J, Netz U, Meinke M J Biomed Opt 2009, 14, 034001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Fredriksson I, Saager RB, Durkin AJ, Stromberg T Journal of Biomedical Optics 2017, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Liu HC, Abbasi M, Ding YH, Roy T, Capriotti M, Liu Y, Fitzgerald S, Doyle KM, Guddati MN, Urban MW, Brinjikji W Phys Med Biol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]