Abstract

Background

Frailty has been associated with increased incidence of postoperative delirium and mortality. We hypothesised that postoperative delirium mediates a clinically significant (≥1%) percentage of the effect of frailty on mortality in older orthopaedic trauma patients.

Methods

This was a single-centre, retrospective observational study including 558 adults 65 yr and older, who presented with an extremity fracture requiring hospitalisation without initial ICU admission. We used causal statistical inference methods to estimate the relationships between frailty, postoperative delirium, and mortality.

Results

In the cohort, 180-day mortality rate was 6.5% (36/558). Frail and prefrail patients comprised 23% and 39%, respectively, of the study cohort. Frailty was associated with increased 180 day mortality from 1.4% to 12.2% (11% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 8.4–13.6), which translated statistically into an 88.7% (79.9–94.3%) direct effect and an 11.3% (5.7–20.1%) postoperative delirium mediated effect. Prefrailty was also associated with increased 180 day mortality from 1.4% to 4.4% (2.9% difference; 2.4–3.4), which was translated into a 92.5% (83.8–99.9%) direct effect and a 7.5% (0.1–16.2%) postoperative delirium mediated effect.

Conclusions

Frailty is associated with increased postoperative mortality, and delirium might mediate a clinically significant, but small percentage of this effect. Studies should assess whether, in patients with frailty, attempts to mitigate delirium might decrease postoperative mortality.

Keywords: frailty, mortality, orthopaedic trauma, perioperative, postoperative delirium

Editor's key points.

-

•

Preoperative frailty is associated with both postoperative delirium and death.

-

•

It is also known that postoperative delirium is associated with postoperative death.

-

•

This study suggests that, in people who are frail preoperatively, postoperative delirium has a potential causal link to death that is independent of the relationship between frailty and death.

-

•

Preventing postoperative delirium is a credible target for mortality prevention in frail people undergoing surgery, and accordingly warrants exploration.

Frailty is a state of decreased functional reserve that is typically characterised by deficits in physical function, nutrition, cognition, and mental health.1 The prevalence of frailty increases with age. In the perioperative setting, studies have demonstrated an association between frailty and postoperative mortality.2, 3, 4 A postulate to explain this association is that surgery and invasive diagnostic procedures result in physiological and biological changes that overwhelm the functional reserve or ability of frail patients to maintain homeostasis. Thus, exercise prehabilitation has been suggested as a strategy to improve the functional reserve of frail patients, and presumably, to mitigate frailty-associated mortality.5,6

Postoperative delirium is an acute disorder of attention and cognition that is associated with frailty7, 8, 9, 10 and increased mortality in the perioperative setting,11 including after orthopaedic trauma.12, 13, 14 Whether the relationship between frailty and mortality is mediated in part by postoperative delirium is unclear. If so, an important clinical implication is that postoperative delirium mitigation strategies could potentially decrease frailty associated mortality. We note that postoperative delirium prevention approaches in the orthopaedic trauma patient population,15, 16, 17, 18 and others, have been successful.19,20

RCTs are typically used to assess causal effects. However, with certain assumptions, causal effects can be estimated from observational studies.21,22 This approach is particularly useful in instances where RCTs may be unethical, impractical, or cost prohibitive. Here, to explore further the relationships between frailty, postoperative delirium, and mortality, we performed mediation analyses to estimate the direct effect of frailty on mortality, and the indirect effect mediated by delirium. Our hypothesis was that postoperative delirium mediates a clinically significant (≥1%) percentage of the effect of frailty on mortality in older, non-ICU, orthopaedic trauma patients.

Methods

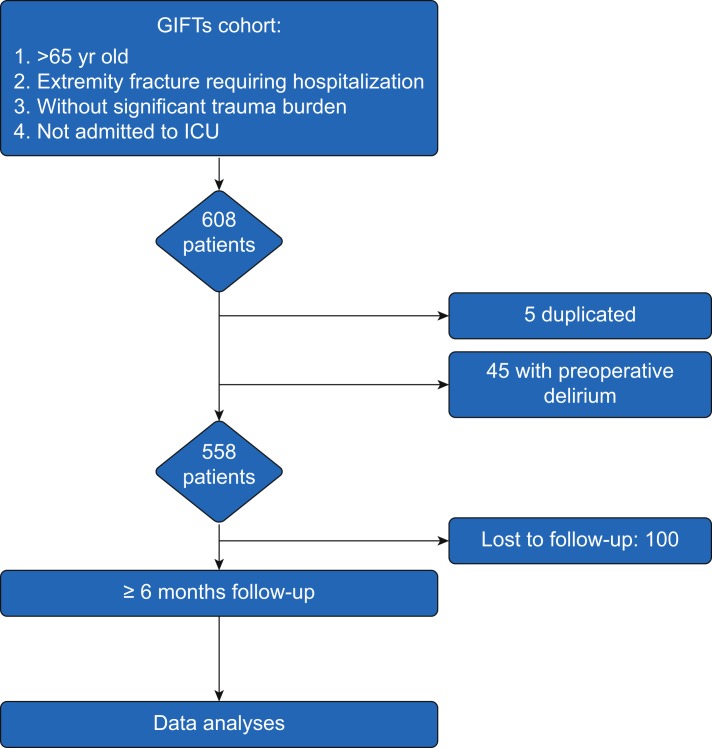

This study is reported following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines and was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee (Boston, MA, USA) Institutional Review Board (IRB number 2016P002331). Written informed consent was waived by the IRB. A flowchart of cohort selection is presented in Fig 1.

Fig 1.

Flow chart of cohort selection. GIFTS, Geriatric Inpatient Fracture Trauma Service.

Study design

This was a retrospective analysis of data from a tertiary academic medical centre.

Setting

A dataset of patients admitted to the Massachusetts General Hospital Geriatric Inpatient Fracture Trauma Service (GIFTS) was analysed. GIFTS is an inpatient consultation service that is staffed by board-certified geriatricians, who assist the primary admitting services with clinical management. Our study cohort consisted of all patients who received a GIFTS consultation between January 2017 and August 2018. Subjects were followed daily through their hospitalisation until discharge. Data on mortality were collected on February 1, 2019. Loss to follow-up dates were obtained from our Medical Health Record System on December 26, 2019.

Participants

Patients were eligible for GIFTS consultation if they were 65 yr or older, presented with an extremity fracture requiring hospitalisation and surgery, did not have significant trauma burden other than orthopaedic injury, and were not admitted to an ICU upon initial hospitalisation. There were no exclusion criteria for GIFTS consultation.

Variables and data sources

Our primary outcome was 180 day postoperative mortality (yes or no). Secondary outcomes included 30 day (yes or no) and 90 day (yes or no) postoperative mortality. Mortality data were obtained from our Medical Health Record System based on healthcare records, obituaries, and Accurint® data. Each patient was followed up for a period between the date of surgery (time 0) to at least postoperative day 180. We defined the loss to follow-up date as the date of death or last medical encounter. Follow-up time was calculated as the interval between the day of surgery (time 0) and the last follow-up date.

Frailty, our exposure of interest, was determined during the initial preoperative GIFTS consultation using the FRAIL scale.23 We also collected data on activities of daily living (Katz ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (Lawton IADL), Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), Functional Ambulation Classification (Ambulation), and number of falls within the past year (Falls).

Postoperative delirium (yes or no), our mediator of interest, was assessed daily during the hospitalisation using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). GIFTS geriatricians at our institution performed a CAM daily, during morning rounds (between 8 am and noon). If they were called during workday hours (from 7 am to 5 pm) by the nursing team because a patient was presenting with acute cognitive changes, a CAM was repeated. If these cognitive changes occurred during the night (from 5 pm to 7 am), it was documented by the nursing team and reviewed the next day by the GIFTs team. We defined postoperative delirium as one or more diagnosis of delirium during the postoperative period between discharge from the PACU to the end of the seventh postoperative day or end of hospitalisation, whichever came first. Patients with preoperative delirium were excluded from our study cohort.

We considered age (continuous), sex (male or female), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI; continuous), BMI (continuous), and cognitive deficit (yes or no) as confounders in our models. Cognitive deficit was recorded as a binary outcome (yes or no) in our dataset and was based on Minicog (positive, 0–2 points) and Global Deterioration Scale (>1) screening tests conducted by geriatricians.

Patient characteristics are summarised using means and standard deviations (sd) for numeric variables, and categorical variables were reported using frequencies and percentages.

Missing data

Data missingness characteristics among study variables were reported using missing frequencies and rates. Missing data were imputed using the multiple imputation with chain equations (MICE) method (m=5).20 The data were pooled using Rubin's rules for averaging.

Mediation analysis

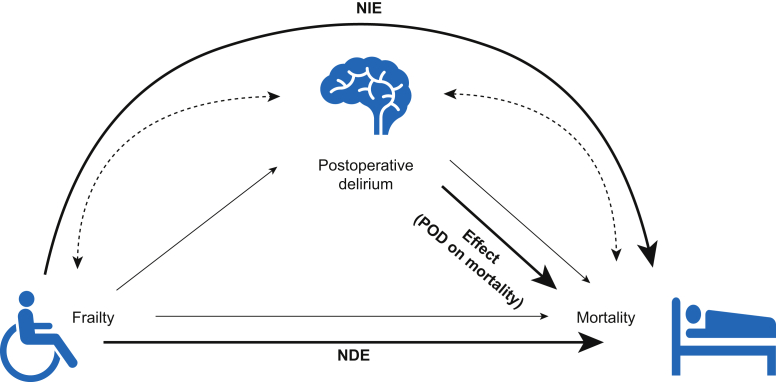

We estimated effects from our imputed dataset with the assumptions encoded in the graph (Fig 2). It is important to note that the estimated effects are valid to the extent that our assumptions are reasonable. We hypothesised that postoperative delirium mediates a clinically significant (≥1%) portion of the effect of frailty on mortality. To understand the effect, one should expect to observe a difference in the outcome (e.g. mortality) in ‘counterfactual’ RCTs, in which one factor (e.g. postoperative delirium) is assigned to all patients, whereas other factors are held constant. In this particular case, it is impractical and unethical to assign postoperative delirium randomly to patients to enable postoperative mortality inferences.

Fig 2.

Directed acyclic graph (DAG) for relation between Frailty, Postoperative Delirium (POD), and Mortality. NDE, natural direct effect; NIE, natural indirect effect; Effect (POD on M): mortality attributable to postoperative delirium.

The total effect (TE) of frailty on mortality can be decomposed into the sum of the natural direct effect (NDE) and natural indirect effect (NIE).21 NDE is the contrast (difference, risk ratio, odds ratio, etc.) between the counterfactual mortality rate if a patient is frail (A=a) vs the (counterfactual) mortality if the same patient instead was robust (A=0), while fixing postoperative delirium to whatever value it would be if the patient was robust (A=0). Here, can be frail or prefrail. Thus, NDE can be intuitively understood as the effect of frailty on mortality through the pathway that does not involve postoperative delirium.

NIE represents the contrast between the counterfactual mortality rate if a patient's frailty state was fixed at robust (A=0), whereas with a postoperative delirium value that took whatever value it would have been for frailty (A=) vs with a postoperative delirium value that took whatever value it would have had for robust (A=0). Equations for TE, NDE, NIE, and their conditional versions, the average treatment effect on the treated (), the NDE on the exposed , and the NIE on the exposed () (i.e. prefrail or frail)24 are:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Our first step was to build three prediction models: (1) frailty model adjusted for age, sex, BMI, cognition deficit, and CCI (propensity model); (2) postoperative delirium model adjusted for frailty, age, sex, BMI, Cognition deficit, and CCI (mediator model); and (3) mortality model adjusted for frailty, postoperative delirium, age, sex, BMI, Cognition deficit, and CCI (outcome model).

The second step was to estimate the potential outcomes , , and . Selected methods for outcome estimation are described in the Supplemental material (Appendix S1).

The third step was to compute the quantities for TE, NIE, NDE, ATT, , and . An unbiased estimation of these values required correct specification of the propensity model, mediator model, and outcome model. To ensure that our models were not sensitive to perturbations because of model misspecification, we minimised the pseudo-risk using the mixed-minmax criterion.25

Finally, we generated 95% confidence intervals (CI) by bootstrapping. First, we generated a bootstrapped dataset with the same number of patients by resampling with replacement from the original dataset. All of the above steps (model fitting, model selection, effect estimation) were repeated on the bootstrapped dataset. This procedure was performed 1000 times to obtain 1000 versions of the effect estimates. The 95% CI was obtained using 2.5% percentile as lower bound and 97.5% percentile as upper bound. Data analyses were performed in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and Python (Python Software Foundation. Available at http://www.python.org).

Bias

Confounding bias was managed by including as many possible confounder variables as possible. Selection bias was minimised by analysing data from all patients that received GIFTS consultation. Data collection by board-certified geriatricians using standardised clinical assessment tools helped to minimise recall bias and measurement error.

Power calculation

This was an analysis of data collected in the GIFTS database. Monte Carlo simulated cohorts were created for power determination. Resampling combinations were generated for observed frailty status, postoperative delirium and mortality using a Monte Carlo approach.26 Considering a sample size of 558 patients, one mediator, 5000 replications, 20 000 Monte Carlo draws per replications with a confidence interval of 95% (α=0.05), we calculated a power of 89% to detect an absolute mediated effect size of 1.0% or greater (equal to 9.9% of the total effect).

Results

Patient characteristics

Data from 558 patients were included in this analysis. The original cohort (n=608) included five duplicated records and 45 patients with preoperative delirium (Fig 1). The incidence of delirium was approximately 12%, and 180 day mortality was approximately 7%. Frailty and prefrailty states comprised 23% and 39% of our study cohort, respectively. These data, stratified by frailty, are presented in Table 1. Surgical type and data missingness characteristics are summarised in the Supplementary material (Appendixes S2 and S3, respectively). Patient characteristics stratified by postoperative delirium status are presented in the Supplementary material (Appendix S4).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Robust | Prefrail | Frail | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 166 | 217 | 126 | 558 |

| Age, yr, mean (sd) | 76.68 (7.49) | 81.14 (8.60) | 83.30 (7.90) | 80.16 (8.57) |

| Height, m, mean (sd) | 1.66 (0.11) | 1.64 (0.10) | 1.62 (0.11) | 1.64 (0.11) |

| Weight, kg, mean (sd) | 73.59 (18.98) | 68.97 (17.42) | 66.97 (20.65) | 69.96 (18.85) |

| BMI, kg m−2 mean (sd) | 26.58 (5.90) | 25.63 (5.49) | 25.16 (6.17) | 25.74 (5.74) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 109 (65.7) | 153 (70.5) | 97 (77.0) | 392 (70.3) |

| Male | 56 (33.7) | 64 (29.5) | 29 (23.0) | 165 (29.6) |

| ASA physical status, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 4 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.1) |

| 2 | 83 (50.0) | 44 (20.3) | 8 (6.3) | 155 (27.8) |

| 3 | 69 (41.6) | 157 (72.4) | 98 (77.8) | 346 (62.0) |

| 4 | 3 (1.8) | 10 (4.6) | 13 (10.3) | 28 (5.0) |

| Anaesthesia type, n (%) | ||||

| General | 136 (81.9) | 185 (85.3) | 106 (84.1) | 470 (84.2) |

| Spinal | 27 (16.3) | 26 (12.0) | 19 (15.1) | 78 (14.0) |

| CCI, mean (sd) | 4.93 (2.16) | 6.36 (2.52) | 7.40 (2.26) | 6.13 (2.52) |

| MNA, mean (sd) | 13.18 (1.39) | 12.03 (2.20) | 9.58 (2.91) | 11.87 (2.53) |

| Katz ADL, mean (sd) | 5.94 (0.53) | 5.54 (1.22) | 3.95 (2.22) | 5.29 (1.59) |

| Lawton IADL, mean (sd) | 7.18 (1.84) | 4.82 (2.84) | 2.29 (2.65) | 5.05 (3.10) |

| Cognition deficit, n (%) | ||||

| No | 129 (77.7) | 138 (63.6) | 62 (49.2) | 346 (62.0) |

| Yes | 30 (18.1) | 62 (28.6) | 45 (35.7) | 146 (26.2) |

| Ambulation, n (%) | ||||

| Dependent | 0 (0.0) | 10 (4.6) | 14 (11.1) | 26 (4.7) |

| Independent | 166 (100.0) | 200 (92.2) | 100 (79.4) | 504 (90.3) |

| No ambulation | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.3) | 7 (5.6) | 13 (2.3) |

| Falls, n (%) | ||||

| None | 127 (76.5) | 119 (54.8) | 48 (38.1) | 318 (57.0) |

| 1 fall | 22 (13.3) | 56 (25.8) | 30 (23.8) | 114 (20.4) |

| 2 or more falls | 15 (9.0) | 33 (15.2) | 38 (30.2) | 93 (16.7) |

| POD, n (%) | 6 (3.6) | 24 (11.1) | 25 (19.8) | 64 (11.5) |

| LOS, mean (sd) | 5.55 (3.05) | 6.55 (4.60) | 7.55 (7.39) | 6.36 (4.93) |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 8 (6.3) | 12 (2.2) |

| 90-day mortality, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 6 (2.8) | 15 (11.9) | 26 (4.7) |

| 180-day mortality, n (%) | 1 (0.6) | 9 (4.1) | 22 (17.5) | 36 (6.5) |

sd, standard deviation; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; MNA, Mini Nutritional Assessment; POD, postoperative delirium; LOS, length of stay.

Effect estimation

To quantify the effect of frailty on 180 day mortality, we estimated the expected mortality for counterfactual RCTs where one group had their frailty set to prefrail, and the other to robust. We found that 180 day mortality increased from 1.4% (95% CI, 0.9–2.3) in the robust to 4.4% (3.5–5.4) in the prefrail (Table 2). The NDE and NIE paths accounted for 92.5% (83.8–99.9) and 7.5% (0.1–16.2) of the prefrailty effect, respectively. The total effect of prefrailty was conserved for 30- and 90-day mortality (Table 2). However, the total effect of prefrailty on mortality was smaller for 90-day mortality, and smallest for 30-day mortality on the difference scale. The ATT or the effect (180-day mortality) on just the exposed (prefrailty) was 3.3% (2.3–4.2). The and paths accounted for 87.5% (67.7–121.2) and 12.5% (–21.2 to 32.3) of the prefrailty effect, respectively. These data and those for 30-and 90-day mortality are summarised in Appendix S5.

Table 2.

Effect estimation

| Outcome | Robust vs which frailty status | %Direct (% NDE) | % Mediated (% NIE) | Potential mortality if all subjects were robust (%) | Potential mortality if all subjects were prefrail (%) | Potential mortality if all subjects were frail (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day mortality | Prefrail | 90.1 (78.8–100.9) | 9.9 (–0.9 to 21.2) | 0.6 (0.2–1.1) | 1.7 (1.1–2.2) | 4.8 (3.2–6.7) |

| Frail | 89.1 (79.7–102.8) | 10.9 (–2.8 to 20.3) | ||||

| 90-day mortality | Prefrail | 87.9 (74.1–101.2) | 12.1 (–1.2 to 25.9) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 3.5 (2.7–4.3) | 8.7 (6.8–10.7) |

| Frail | 84.5 (74.0–93.1) | 15.5 (6.9–26.0) | ||||

| 180-day mortality | Prefrail | 92.5 (83.8–99.9) | 7.5 (0.1–16.2) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) | 4.4 (3.5–5.4) | 12.2 (10.0–14.4) |

| Frail | 88.7 (79.9–94.3) | 11.3 (5.7–20.1) |

NDE, natural direct effect; NIE, natural indirect effect.

For a counterfactual RCT where one group had their frailty set to frail and the other to robust, the 180-day mortality would increase from 1.4% (0.9–2.3) to 12.2% (10–14.4). The NDE and NIE paths accounted for 88.7% (79.9–94.3) and 11.3% (5.7–20.1) of the frailty effect, respectively. The total effect of frailty was conserved for 30 and 90 day mortality (Table 2). However, this effect was smaller for 90 day mortality, and smallest for 30 day mortality on the difference scale. The ATT or the effect (180 day mortality) on just the exposed (frailty) was 14.4% (11.1–17.5). The NDEexposed and NIEexposed paths accounted for 96.4% (83.9–108.8) and 3.6% (–8.8 to 16.1) of the prefrailty effect, respectively. These data and those for 30 and 90 day mortality are summarised in Appendix S5.

Discussion

We investigated whether postoperative delirium mediates a clinically significant portion of the effect of frailty on 180-day mortality. Our results suggest that in orthopaedic trauma patients ≥65 yr old who were not initially admitted to the ICU, frailty was associated with increased mortality from 1.4% to 12.2%. Postoperative delirium mediated only approximately 11% of the excess 180-day mortality (% NIE, postoperative delirium mediated effect) in frail patients. In secondary analyses, we found that postoperative delirium was a mediator in our analyses of the effect of frailty on 90-day mortality, but not 30-day mortality. This finding may be secondary to lower precision in the estimates for the shorter period represented by 30-day mortality rather than actual differences between the estimated fraction of mortality mediated through delirium.

In their meta-analysis, Hamilton and colleagues27 suggested that the association between delirium and increased mortality may be secondary to confounding. They reported that, as control for confounding improves, the effect of postoperative delirium on mortality becomes substantially smaller than previously reported. The authors concluded that studies with low risk-of-bias are necessary to solidify our understanding of the delirium–postoperative mortality relationship.27 However, these studies are not always feasible or ethical. In this research, we aimed to estimate the delirium mediated contribution of frailty to 180-day mortality. We adjusted for previously reported confounders such as age, sex, CCI, BMI, and cognitive status.27 Our findings suggest a causal, albeit small, relationship between postoperative delirium and mortality. However, whether unknown covariates are sufficient to explain away the causal association between delirium and mortality is unknown.

The Perioperative Quality Initiative recently recommended the use of multicomponent non-pharmacologic interventions for the prevention of postoperative delirium in older high-risk patients (strong recommendation, grade B).28 Geriatric consultation is fundamental to most multi-component delirium prevention bundles, and tested individually, has been shown to reduce the incidence of delirium in the orthopaedic trauma population.17 18 However, the incidence of postoperative delirium in our entire cohort was approximately 12% despite geriatric consultation. This suggests other delirium prevention strategies such as structured management pathways29 and pharmacologic interventions30, 31, 32 may be necessary to further reduce the burden of postoperative delirium.

A major strength of our study is that board-certified geriatricians performed comprehensive assessments (frailty, cognitive, delirium, etc.) and were responsible for medical care in our study cohort. However, our study has several limitations. First, frailty and postoperative delirium are complex multifactorial constructs with non-standard measurement characteristics.33 Thus, multiple sources of residual confounding may have biased our results. However, the pseudo-risk minimisation method we used ensured that our selected models and inferential framework are robust. Second, we studied older orthopaedic trauma patients who were clinically managed by geriatricians. Thus, our results may not be generalisable to other cohorts such as general surgical patients. However, our homogenous and well characterised patient population may enable previously underappreciated insights and foster reproducibility. Third, our lost to follow-up rate was high, and imputation assumptions may introduce confounding. Fourth, our selection criteria, which excluded ICU patients, could have underestimated the real prevalence of frailty in this population leading to a selection of healthier patients. Finally, our findings may have been affected by random noise inherent the relatively modest number 180 day mortality events in our dataset.

We conclude that postoperative delirium mediates a clinically significant (≥1%) portion of the effect of frailty on mortality in orthopaedic trauma patients ≥65 yr old that did not require ICU care on initial admission to a tertiary medical care centre. Thus, if processes that are dependent or associated with delirium cause mortality, reducing the incidence of postoperative delirium, might be expected to result in a clinically significant reduction of postoperative mortality. However, it is important to note that delirium accounted only for a small fraction of the effect of frailty on mortality. Thus, future prospective studies in various surgical populations are necessary to inform approaches to better mitigate the effect of frailty on postoperative mortality.

Author's contributions

Analysis: JCP, HS, EFG, SQ, MBW, OA

Interpretation of the work: JCP, HS, EFG, SQ, MBW, OA

Coding: HS

Data extraction: HS, MH

Data generation and verification: CZ, MH

Drafting of the manuscript: JCP, EFG, SQ, MBW, OA

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JCP, HS, EFG, SQ, MBW, OA

All authors were involved in the design and execution of the work; gave final approval of the version to be published; and accepted accountability for all aspects of the work.

Funding

National Institute of Health, National Institute on Aging (grant number RO1AG053582) to OA; Glenn Foundation for Medical Research and the American Federation for Aging Research through a Breakthroughs in Gerontology Grant, American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation Strategic Research Award, National Institute of Health (grant numbers 1R01NS102190, 1R01NS102574, 1R01NS107291, and 1RF1AG064312) to MBW; División de Anestesiología, Escuela de Medicina, Pontificia Universidad Caólica de Chile to JP; and Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care, and Pain Medicine, to MGH and OA.

Declarations of interest

OA has received speaker's honoraria from Masimo Corporation and is listed as an inventor on pending patents on EEG monitoring that are assigned to Massachusetts General Hospital, some of which are assigned to Masimo Corporation. OA has received institutionally distributed royalties for these licensed patents. All other authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Handling editor: Michael Avidan

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2021.03.033.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary material is available at British Journal of Anaesthesia online.

References

- 1.Childs B.G., Durik M., Baker D.J., van Deursen J.M. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: from mechanisms to therapy. Nat Med. 2015;21:1424–1435. doi: 10.1038/nm.4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIsaac D.I., Bryson G.L., van Walraven C. Association of frailty and 1-year postoperative mortality following major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:538–545. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIsaac D.I., Moloo H., Bryson G.L., van Walraven C. The association of frailty with outcomes and resource use after emergency general surgery: a population-based cohort study. Anesth Analg. 2017;124:1653–1661. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James L.A., Levin M.A., Lin H.M., Deiner S.G. Association of preoperative frailty with intraoperative hemodynamic instability and postoperative mortality. Anesth Analg. 2019;128:1279–1285. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borrell-Vega J., Esparza Gutierrez A.G., Humeidan M.L. Multimodal prehabilitation programs for older surgical patients. Anesthesiol Clin. 2019;37:437–452. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milder D.A., Pillinger N.L., Kam P.C.A. The role of prehabilitation in frail surgical patients: a systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62:1356–1366. doi: 10.1111/aas.13239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown C.H., 4th, Max L., LaFlam A. The association between preoperative frailty and postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:430–435. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watt J., Tricco A.C., Talbot-Hamon C. Identifying older adults at risk of delirium following elective surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:500–509. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4204-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahanna-Gabrielli E., Zhang K., Sieber F.E. Frailty is associated with postoperative delirium but not with postoperative cognitive decline in older noncardiac surgery patients. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:1516–1523. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evered L.A., Vitug S., Scott D.A., Silbert B. Preoperative frailty predicts postoperative neurocognitive disorders after total hip joint replacement surgery [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 27] Anesth Analg. 2020;10 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000a000000004893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bai J., Liang Y., Zhang P. Association between postoperative delirium and mortality in elderly patients undergoing hip fractures surgery: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31:317–326. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radinovic K., Markovic-Denic L., Dubljanin-Raspopovic E., Marinkovic J., Milan Z., Bumbasirevic V. Estimating the effect of incident delirium on short-term outcomes in aged hip fracture patients through propensity score analysis. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15:848–855. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radinovic K.S., Markovic-Denic L., Dubljanin-Raspopovic E., Marinkovic J., Jovanovic L.B., Bumbasirevic V. Effect of the overlap syndrome of depressive symptoms and delirium on outcomes in elderly adults with hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1640–1648. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottschalk A., Hubbs J., Vikani A.R., Gottschalk L.B., Sieber F.E. The impact of incident postoperative delirium on survival of elderly patients after surgery for hip fracture repair. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:1336–1343. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjorkelund K.B., Hommel A., Thorngren K.G., Gustafson L., Larsson S., Lundberg D. Reducing delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture: a multi-factorial intervention study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:678–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundstrom M., Olofsson B., Stenvall M. Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19:178–186. doi: 10.1007/BF03324687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcantonio E.R., Flacker J.M., Wright R.J., Resnick N.M. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:516–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deschodt M., Braes T., Flamaing J. Preventing delirium in older adults with recent hip fracture through multidisciplinary geriatric consultation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:733–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen C.C., Lin M.T., Tien Y.W., Yen C.J., Huang G.H., Inouye S.K. Modified hospital elder life program: effects on abdominal surgery patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin F.H., Neal K., Fenlon K., Hassan S., Inouye S.K. Sustainability and scalability of the hospital elder life program at a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:359–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearl J. 2013. Direct and indirect effects; p. 13012300. arXiv. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearl J. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2009. Causality. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morley J.E., Malmstrom T.K., Miller D.K. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:601–608. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0084-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vansteelandt S., Vanderweele T.J. Natural direct and indirect effects on the exposed: effect decomposition under weaker assumptions. Biometrics. 2012;68:1019–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2012.01777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui Y., Tchetgen Tchetgen E. vol. 1911. 2019. (Selective machine learning of doubly robust functionals). arXiv. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoemann A.M., Boulton A.J., Short S.D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2017;8:379–386. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton G.M., Wheeler K., Di Michele J., Lalu M.M., McIsaac D.I. A systematic review and meta-analysis examining the impact of incident postoperative delirium on mortality. Anesthesiology. 2017;127:78–88. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes C.G., Boncyk C.S., Culley D.J. American society for enhanced recovery and perioperative quality initiative joint consensus statement on postoperative delirium prevention. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:1572–1590. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berger M., Schenning K.J., Brown C.H. Best practices for postoperative brain health: recommendations from the fifth international perioperative neurotoxicity working group. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:1406–1413. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akeju O., Hobbs L.E., Gao L. Dexmedetomidine promotes biomimetic non-rapid eye movement stage 3 sleep in humans: a pilot study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2018;129:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2017.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamadia S., Hobbs L., Marota S. Oral dexmedetomidine promotes non-rapid eye movement stage 2 sleep in humans. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:1234–1243. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chamadia S., Pedemonte J.C., Hobbs L.E. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of oral dexmedetomidine. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:1223–1233. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh E.S., Akeju O., Avidan M.S. A roadmap to advance delirium research: recommendations from the NIDUS Scientific Think Tank. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16:726–733. doi: 10.1002/alz.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.