Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic developed the severest public health event in recent history. The first stage for defence has already been documented. This paper moves forward to contribute to the second stage for offensive by assessing the energy and environmental impacts related to vaccination. The vaccination campaign is a multidisciplinary topic incorporating policies, population behaviour, planning, manufacturing, materials supporting, cold-chain logistics and waste treatment. The vaccination for pandemic control in the current phase is prioritised over other decisions, including energy and environmental issues. This study documents that vaccination should be implemented in maximum sustainable ways. The energy and related emissions of a single vaccination are not massive; however, the vast numbers related to the worldwide production, logistics, disinfection, implementation and waste treatment are reaching significant figures. The preliminary assessment indicates that the energy is at the scale of ~1.08 × 1010 kWh and related emissions of ~5.13 × 1012 gCO2eq when embedding for the envisaged 1.56 × 1010 vaccine doses. The cold supply chain is estimated to constitute 69.8% of energy consumption of the vaccination life cycle, with an interval of 26–99% depending on haul distance. A sustainable supply chain model that responds to an emergency arrangement, considering equality as well, should be emphasised to mitigate vaccination's environmental footprint. This effort plays a critical role in preparing for future pandemics, both environmentally and socially. Research in exploring sustainable single-use or reusable materials is also suggested to be a part of the plans. Diversified options could offer higher flexibility in mitigating environmental footprint even during the emergency and minimise the potential impact of material disruption or dependency.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, Energy and emissions, Environmental impact, Cold supply chain, Sustainability, Interdisciplinary analysis

Nomenclature

- COVAX

COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- EU

European Union

- GHG

Greenhouse gas

- GMP

Good Manufacturing Practice

- IATA

International Air Transport Association

- MBW

Microbiology and Biotechnology Waste

- mRNA

Messenger ribonucleic acid

- NHPW

Non-Hazardous Pharmaceutical Waste

- PPE

Personal Protection Equipment

- RMW

Regulated Medical Waste

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- R&D

Research and development

- SDGs

Sustainable Development Goals

- SDS

Sharps Disposal Solutions

- UK

United Kingdom

- UNICEF

United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund

- WHO

World Health Organization

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has reached a worldwide scale and influenced life on a global scale [1]. The International Monetary Fund estimated a total of US$ 2.8 × 1013 cost in 2020 due to the global COVID-19 pandemics [2]. The impacts on energy and the environment cover many fields, such as waste-to-material and waste-to-energy [3], urban sustainability in terms of economic and the environment [4], and energy stock markets [5]. At the beginning of the year 2020, COVID-19 looked by most of the population as just another epidemic, which might influence one or just a few regions, just like the severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003. However, the speed, spread and scale outperformed even very pessimistic scenarios. Despite all the protective actions which came a few times in some places to the total lockdown, the numbers of infected are growing fast. The first 10 M confirmed cases took around six months, the 2nd took one and half months, the 3rd took 35 d, the 8th took only 16 d, and the latest, the 9th only took 11 d [6]. To date, over 163 M confirmed cases and closing to 3.4 M related deaths were reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) [7]. However, from the peak reached 8 January 2021 with 845,267 reported cases, the figures started to drop considerably. It shows an obvious influence of vaccination, especially by reducing mortality, which has been clearly demonstrated by statistics from countries where the vaccination is progressing fast as Israel and the USA. However, from the saddle point, around 20 February 2021, the increase in infections related to spreading out to high populous countries and due to virus mutation and new strains started again. However, due to the number of supplied vaccines, the daily numbers of deaths are slowing, which are in line with the numbers of infected people in those countries with proper measures.

By 18 May 2021, more than 1.48 × 109 vaccine shots have been given [8], and the numbers are growing fast. During the COVID-19 pandemic, besides the crucial challenges – medical services and treatments, there are also energy and environmental issues related to vaccination to be dealt with. This is the main focus of this paper.

Even under this critical situation, when the priorities considerably shifted in the fight for the population's survival, the environmental impact should not be neglected. As many studies and advanced research developments have been demonstrating that the pandemic can be used as an inhibitor for a positive change and, if properly managed, as an innovation accelerator that triggered the sixth innovation wave [9]. The struggle to contain the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has become documented from various points of view [10]. One of the first studies dealing with the environmental impact of Personal Protection Equipment (PPE), disinfection and testing [11] has become fast a highly cited paper, which demonstrates the wide attention to the related issues. However, there are also strong impacts on sustainable waste management [12] and energy consumption and generation [13], as well as notable on the increased energy demand to lead the struggle with infection [14]. In the current phase, some studies also reviewed the impacts of COVID-19 on multiple sectors, such as renewable energy and the environment [15], the short- and long-term energy and the environment [16], and the healthcare, energy and environment [17]. Now the war with the virus entered is the second offensive stage, which can hopefully bring the world population closer to epidemic defeat ─ mainly vaccination. With the rapid development of vaccines, the prevention and control of pandemics have entered this second stage.

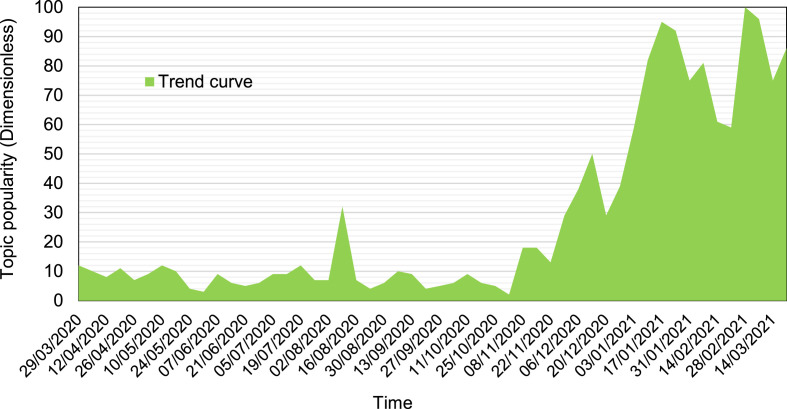

It has appeared some first light “at the end of the tunnel”. By the concentrated and focused effort of leading laboratories on this planet, more and more vaccines have been developed [18], tested [19], and gradually authorised for safe use. In history, the development of a licensed vaccine needs several years, even at the colouration speed [20]. The institutions and companies make it possible within one year under the emergent situations of global COVID-19 pandemics. Fig. 1 shows that the topic popularity of “vaccine for COVID-19” increases sharply after November 2020, especially after the announcement regarding the nearly 95% protection from Pfizer & BioNTech vaccines [21] and similar results from Moderna [22]. However, new challenges appeared with increasing appearing new strains. Intuitively, the world came into the COVID-19 Pandemics Stage II when new hopes and practices with effective vaccines accompany the population. Came to the year 2021, vaccination and vaccines become the most popular keywords under the haze of the COVID-19 pandemics. However, there is a paucity of literature on emphasising the importance of the energy and environmental impacts of vaccination, and it is subject to, in the same cases, sharp changes and fluctuations. This communication assesses and discusses this timely and challenging issue.

Fig. 1.

The trend of popularity of “vaccine for COVID-19” over time. The data are retrieved from Google Trends [23].

The assessment and applications of mass vaccines are tasks of medical expert teams and governments. From a perspective of environmental management, what are also needed to be assessed include the energy and environmental footprints/impacts and the reduction and possibly minimisation of the impacts. This study overviews and assesses the vaccination process in terms of the vaccination requirements, the logistics and vaccine distribution, as well as the related vaccination waste management. Based on currently available quantitative information, energy and environmental footprints are assessed approximately, which triggers suggestions for mitigating and reducing environmental footprints. Lessons, readiness and opportunities related to COVID-19 vaccination are also discussed for possible future pandemics.

2. Vaccination process

Vaccination is supposed to be a mass process with a large number of units needed. It is estimated that the production capacity of around 1 × 1010 doses of COVID-19 vaccination would be achieved by the end of 2021, including 20 manufacturers worldwide [24]. Based on the estimation of Wang et al. [25], around 68% of the population worldwide is willing to take the COVID-19 vaccination, which means that about 3.7 × 109 people need to be vaccinated. Just India is planning to vaccinate 3 × 108 citizens in the first step [26]. The mathematical models suggested that vaccines will not be enough until 2023 [27], considering multiple factors such as the limited sources, manufacturing capacity and population coverage. There are different estimations for the emergent need for vaccination. Crommelin et al. [28] estimated that the 5–10 × 109 vaccine doses are required for global distribution. The DHL Express team claimed around 1 × 1010 vaccine doses are needed over the long term [29].

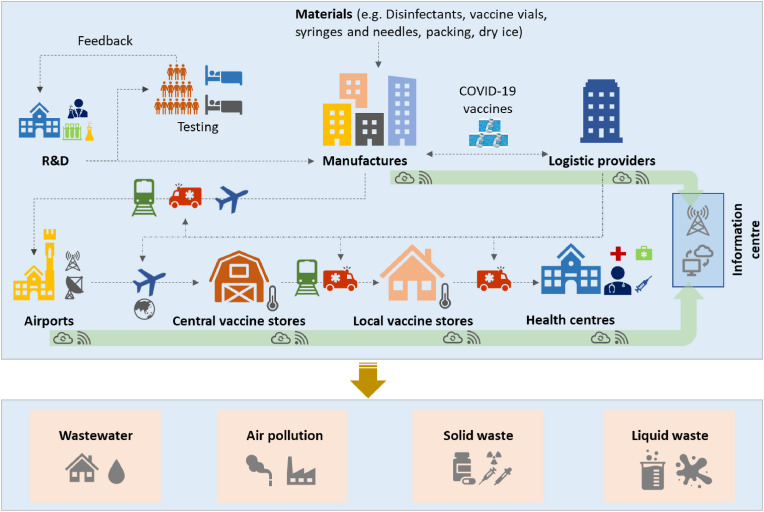

Fig. 2 shows the diagram of a vaccination process from sources to end consumption. The research and development (R&D) started at the occurrence of global pandemics, which involves broad testing with three typical phases. Multiple organisations/companies, such as government agencies, manufactures, logistic companies, medical institutions and non-governmental organisation institutes, would participate in the production, distribution and services of vaccination. Multiple transportation modes, including aircraft, train and cars, cooperate for the distribution of vaccines from production places, to airports, to central vaccine stores, local vaccine stores and health centres. In the whole process, R&D, materials and resources, production, logistics, waste treatment and vaccination management would be a global system-engineering project, which is detailed as follows.

Fig. 2.

The diagram of a vaccination process – from sources to end consumption.

2.1. Research & development

The occurrence of pandemics triggers the R&D of COVID-19 vaccines. Table 1 shows typical phases of vaccine production and goals for the process/system. It includes.

-

(a)

Experimental & preclinical step,

-

(b)

Clinical research authorisation documentation, application and approval,

-

(c)

Phase I vaccine trials,

-

(d)

Phase II vaccine trials,

-

(e)

Phase III vaccine trials,

-

(f)

Vaccine approval and licences,

-

(g)

Post trademark licence monitoring, and

-

(h)

Post licence modification.

Table 1.

Key stages of vaccine production and goals for process/system.

| Stage | Objective | Process development and manufacturing |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental & preclinical step |

|

|

| Clinical research authorisation documentation, application and approval |

|

|

| Phase I vaccine trials |

|

|

| Phase II vaccine trials |

|

|

| Phase III vaccine trials |

|

|

| Vaccine approval and licences |

|

|

| Post trademark licence monitoring |

|

|

| Post licence modification |

|

|

More details of the R&D of COVID-19 vaccines are referred to as the progress of COVID-19 vaccine development [30] and the challenges of developing a vaccine for COVID-19 [19].

2.2. Key materials and resources for vaccines

There are many required materials and resources for vaccines, such as disinfectants, vaccine vials, syringes and needles, dry ice and packing materials.

2.2.1. Disinfectants

The global disinfectant market had risen at a compound annual growth rate of 17.2% from US$ 0.66 × 109 in 2019 to US$ 0.78 × 109 in 2020 for preventing the pandemic. In the majority of cases, coronavirus infection is transmitted by contact with surfaces/objects infected. Chemical disinfectants inactivate the virus. The demand for disinfectants was remarkably increased for pandemic and vaccination process [39]. Growing infections and vaccination processes acquired by hospitals have increased global spending on disinfectant solutions. The hospital sector accounted for the largest share of the demand for surface disinfectants in 2020. Surface disinfectants are segmented on end-users into hospital environments, research laboratories, vaccines centres, pharmaceutical firms and biotechnology laboratories [40].

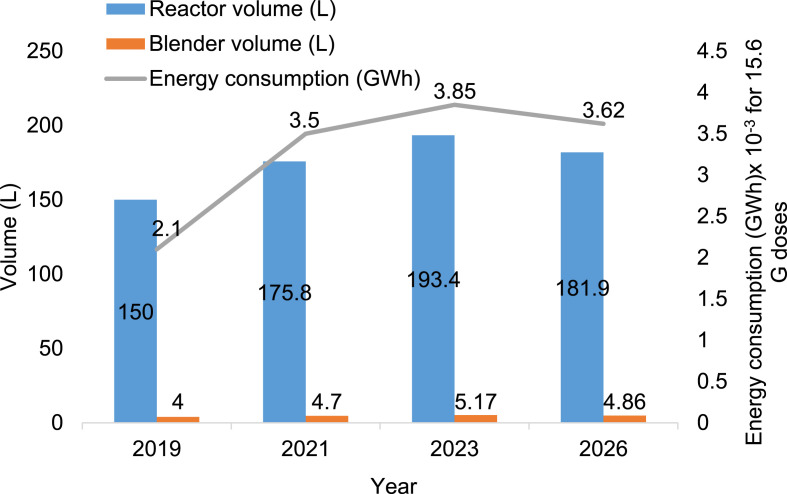

All end-users are expected to account for the largest share of the market in surface disinfection in 2026 in the hospital environment and vaccination category. Fig. 3 depicts the energy consumption of disinfectants production by considering the continuous stirred-tank reactor on the basis of 1.56 × 1010 vaccine doses [41]. E.g., for the 1,000 doses of vaccine/d: the jab of each person takes less than 5 min; however, the medical consultation before and to stay after to avoid fast accruing side effects needs about 30 min. The total estimated time to stay at the vaccination centre is approximately 45 min. The assumption of a 4 m × 3 m area required the disinfectant of 9 L/d. The 10 L/d disinfectant needs to be used by sanitation walk-through for 1,000 person/doses vaccinated (total 19 L/d) [42]. The disinfectant reactor power consumption data was obtained from an industrial plant manufacturer for sensitisation products [43]. The energy consumption is increased by 17.2% from the year 2019–2020 [41]. It is predicted to be increased by 10.02% by 2023. It was projected by Research and Markets [41] that the energy consumption, cost and demand of disinfectants would be decreased by 5.92% by the year 2026.

Fig. 3.

Energy consumption estimation for disinfectants production by considering the mixing tank reactor for 1.56 × 1010 (i.e. 15.6 G) doses of vaccine.

2.2.2. Vaccine vials

The lack of glass vials can be a bottleneck for vaccination campaigns. The two jabs are generally required for each person receiving a vaccine, reports claim, creating an imminent potential need of up to 1.56 × 1010 doses (1 dose = 2 or more jabs), and this might be more complicated for kids [44]. The vials are still also required for current health care and vaccines. Vaccine manufacturers usually overfill their vials to take daily waste lightly into account when dosages are made and given [45]. The Pfizer bottle was initially destined for five (0.3 mL) doses or a total of 1.5 mL. When the vaccine was injected, it actually contained 2.25 mL of vaccine. Modern vials for 10 mL, 5 mL total, are typically 6 mL of a jab. The excess vaccine, which takes up to two extra jabs in Pfizer's five-dose vial and Moderna's ten-dose vials, would save lives as the pandemic still kills many in the world every day [45]. Despite the fear of vaccination success guarantee, manufacturers also want to secure their proportion of glass vials.

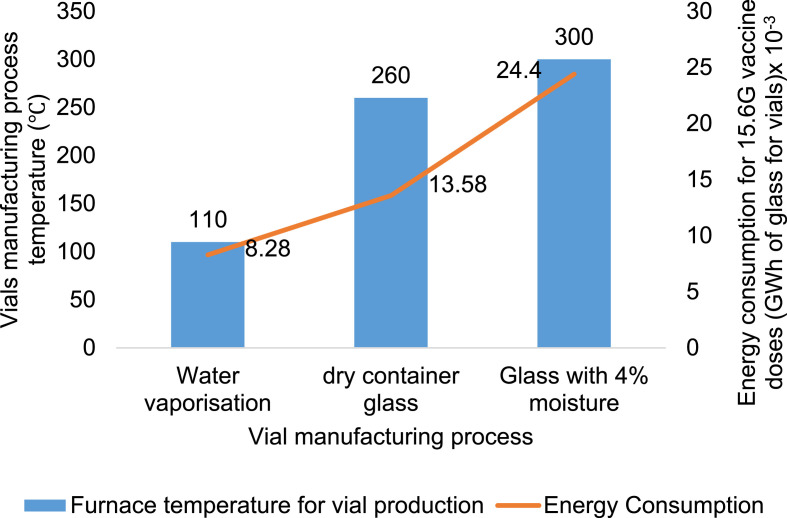

Potential vaccines are being developed and, although the vial shortage is immense, public-private partnerships focused on strategic planning and technical progress will possibly be resolved [46]. Fig. 4 describes the vials manufacturing processing with the energy consumption rate. The energy consumed for 1.56 × 1010 doses was calculated on the basis of raw material utilised 1 t/d. The 2 × 106 vials (5 mL vial) are assumed to be produced per ton of raw material. The mass of the vial was calculated by the density of the vaccine vial [47]. The glass melting with 4% of moisture consumed 24.4 GWh of vials production at 1,500 °C. The moisture or water vaporisation from the process involves 67.9 kWh of energy consumption at 550 °C. The production of glass vials is an energy-intensive process at high temperatures. Annual energy consumption was around 0.98 TWh. The furnaces were used to melt the glass with more than 70% steam/fuel. These furnaces are responsible for fuel-related CO2 emissions of around 650 kt/y [48].

Fig. 4.

Energy consumption by the vial manufacturing processes for 1.56 × 1010 of vaccine doses [48].

2.2.3. Syringes

On December 14, 2020, the first American vaccine was performed on healthcare staff and residents of long-term care facilities. The authorities experienced a cutting edge of one vital piece of equipment about vaccinations, i.e. syringes. The USA turned away a deficiency of syringes on account of early orders, which included a request for more than 2.8 × 108 syringes from Becton Dickinson and Co., the world's top syringe maker, and a US$ 6.0 × 108 credit to ApiJect for future utilisation. Developing countries, Brazil, China, India, etc., should be able to fulfil their syringe demand by incredibly increasing the capacity with the help of local manufacturers [49].

The syringes distribution chain for daily basis medication and drug supply should not be disturbed. The world generates about 1.6 × 1010 of disposable syringes/y, according to the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and about 5% are used for various vaccinations (the rest are for administering drugs, drawing blood, and other uses) [50]. The demand for non-vaccine syringes this year was reduced as fewer people are going to hospitals for elective procedures. Traditionally, syringes are not recycled because it is more economical to simply manufacture a new one. However, this means increased material, energy, emissions and waste [50].

Standard 3 mL vaccine syringe but a thinner 1 mL vaccine syringe, like Pfizer's and Moderna's, is also used in small dose vaccines. It is specially made for “low dead volume” syringes in both sizes and fed into the needle to remove much of this trapped liquid. The use of these massive and monstrous 3 mL syringes with a high dead-space device is essential in order to achieve the exact dosage [45]. The output capacity of the syringe manufacturing process is 150 kg/h (5 mL syringe) with an annual production of 15 × 106 syringes with 215 kWh energy consumption. A total of 223 GW energy is required to meet 1.56 × 1010 of doses [51]. Even when idle, hydraulics consumes a lot of electricity. During an injection moulding operation, a standard electrical machine can use approximately 2.55 kWh, but hybrid moulding uses 3.83 kWh, and hydraulic machines can use 5.12 kWh. They need higher moulding temperatures and longer cooling time [52].

2.3. Vaccines

Vaccine developers have been on the way to deliver enough vaccine doses to more than 1/3 of the world's population by the end of 2021. Many citizens in low-income countries are likely not to be getting the vaccines for the next two years, i.e. 2022-2023. Various producers have scaled back their respective sales forecasts over time.

There are more than 100 vaccine candidates in development. By 23 March 2021, there are 45 vaccine candidates in Phase I, 32 candidates in Phase II, 23 candidates in Phase III, 6 vaccines in early or limited use, 7 vaccines approved for full use, and unfortunately 4 vaccines abandoned after trials [53]. Table 2 shows the comparison of some typical COVID-19 vaccines. Overall, they are all temperature-sensitive products, especially that the Messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) type vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna) have a strict requirement of storage temperature. There are always some trade-offs between delivery and financial cost, which make vaccine distribution to be challenging. For example, for Sputnik V, the second type is more convenient for storage and transportation and was intended for delivery and use in remote regions of Russia, while the first one is cheaper and more technologically advanced in production. For this reason, it is planned to use the frozen version for general vaccination of the population [54].

Table 2.

Comparison of typical global vaccines.

| Vaccines | Country | Type | Efficiency rate | Recommended interval between | Storage temp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pfizer a | USA & Germany | mRNA | ~95.0% | 21 d | −70.0 °C |

| Moderna a | USA | mRNA | ~95.0% | 21 d | −20.0 °C |

| Sinovac a | China | Inactivated virus | 79.9% | 14 d | 2.0–8.0 °C f |

| Sinopharm b | China | Inactivated virus | 79.3% | 14–28 d | 2.0–8.0 °C |

| Sputnik V c | Russian Federation | Viral two-vector | 91.6% | 21 d | −18.0 °C (frozen) or 2.0–8.0 °C (lyophilised)g |

| Oxford/AstraZeneca d (now Vaxzevria e) | British-Swedish | ChAdOx1 virus | 79.0% | 8–12 d | 2.0–8.0 °C |

| Covaxin | Bharat Biotech. India | Inactivated virus | 81.0% h | 28 d | 2.0–8.0 °C |

| Johnson & Johnson i | Janssen Biotech, Inc., PA USA | Viral vector | 68.0% | Single dose | 2.0–8.0 °C |

2.4. Manufacturing and production

Major vaccine manufacturing, production and utilisation requirements are presented in Table 3 . The vaccine manufacturers can have clear insight into population patterns, including birth cohort size, and can forecast domestic market size quickly. If the population served by a local manufacturer is limited, the costs of developing and building a vaccine are distributed over fewer doses, which results in high costs of production per unit [62]. Larger producers also intend to supply several markets using a commercial plan (e.g., additional countries or broader income-based market segments). Large amounts of products benefit a lower cost, with high fixed costs diluted in many doses. The failure to forecast competition and demand properly across multiple markets would lead to overcapacity and increase costs as production facilities and supporting centres are not used optimally. An innovative vaccine type or new disease field can have specific challenges as early on. Vaccine developers may not be fully aware of the precise mechanism of vaccine action or the effect of the vaccine on disease [62].

Table 3.

Important vaccine manufacturing, production and utilisation requirements.

| Cost driver | Major cost | Relative Impact of Overall Cost | Cost range | Energy-related values | Options to reduce the cost of goods sold | Potential Impact of lower vaccine distribution strategy | Vaccine Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Development | R&D Laboratories and personnel | High fixed costs/possible to be shared across antigens | >500 M US$ Risk-adjusted* cost of 135–350 M US$ *Risk adjusted cost incorporates the cost and probabilities of moving to the next phase of development [62]. |

Each manufacturing pharmaceutical required 3.34 kWh of power/g of vaccine (1 dose = 100 μg of mRNA. Let's considered energy emissions for the 10 key manufacturing companies for COVID-19 vaccines [64]. A total of ten manufacturers required a total energy consumption of 2.37 × 102 kWh of power*. *These energy estimates were converted to their carbon emission equivalents at the rate of 2.7 kg CO2/L of fuel, 1.64 kg CO2/kWh of grid electricity and 0.43 kg CO2/kWh of solar-generated electricity [65] |

Copy originator process post-patent expiration | High | MR (measles and rubella) vaccine copied from originator vaccine |

| Perform technology transfer with established product | High | ||||||

| Leverage correlates of protection to avoid large efficacy studies | Medium | ||||||

| Purchase antigens and execute form/fill as a means of gaining experience before full manufacturing end-to-end | Medium | OPV (oral polio vaccine) bulk can be sourced from approved manufacture and formulated/filled | |||||

| Direct Labour | Employee costs directly attributable to a specific vaccine Salaries Benefits |

Low/typically less than 25% of total manufacturing cost | Costs can be significantly lower in China and India (25% lower for some manufacturers). The difference is shrinking due to increasing labour cost as the requirements of good manufacturing (cGMP) practices increase [66] | Increase automation and single-use production technologies (balancing with a potential increase in equipment or consumables costs | Medium | Single-use, or disposable, bioreactors reduce cleaning and sterilisation requirements, and complexity of qualification and validation Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine assays are streamlined across multiple serotypes. |

|

| Standardise and streamline processes across as many steps and vaccines as possible. Develop capacity progressively through reverse integration (packaging purchased products, filling and packing purchased products, form/fill/pack purchased products, then production of bulk drug substance for internal form/fill/pack) [67] |

High | – | |||||

| Licensing/Regulatory and vaccine commercialisation | Expenses paid for the right to use product-related IP (technology) Expenses to comply with regulatory requirements to produce either for the domestic market or export |

Low if experienced teams are engaged early to prepare facilities and processes for regulatory review and higher if the review process requires considerable rework or if delays result in lost revenue | In addition to staff and consulting costs, the new WHO process assesses the following fees: A site audit fee of 30 k US$ and for: Simple/Traditional vaccines: Evaluation fee of 25–100 k, and Annual fees of 4.8 k to 140 k US$ Combo or Novel Vaccines: Evaluation fee of 66.5–232.8 k US$, and Annual fees of 8.4–250 k US$ [63] |

Energy is calculated based on one manufacturing company is under one licencing authority, product commercialisation, and utilities*. The 6.68 × 102 kWh/y power needed for each vaccine company [68]. The cost of electricity for a commercial user is 0.109 US$/kWh in the Czech Republic [69]. The total cost needed for a company based in the Czech Republic cost is 7.2 M US$/y. * The energy was calculated by considering one unit of licensing, management, IT or utilities section. Each unit assumed to be operated with a staff of 5 persons, which using energy in the form of electric power for 40 h of work per week. |

Pursue WHO PQ as required by UNICEF/PAHO only when intending to access markets for which they procure (e.g., Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation) | – | – |

| Request royalty reductions or waivers for vaccine sold in low-income countries (LICs) | Low | Royalty for human papillomavirus vaccines antigens waived for volumes sold in Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation | |||||

| Produce reagents in-house or seek viable alternatives rather than a license. | Medium | CRM produced in-house to avoid licensing cost. | |||||

| Differentiate originator production processes sufficiently to be considered a novel process | – | – | |||||

| Accelerate approval by seeking NRA or WHO priority review for vaccines for neglected diseases or emergency use. | High | – | |||||

| Utilise FDA priority review vouchers for another product and allocate savings to the vaccine that secured the voucher. | High | Apply priority review voucher to a product intended for high-income markets to maximise the value of approval | |||||

| Over head | Management, quality systems, IT systems | High if a company has few products and low if overhead can be allocated across multiple products | Up to 45% of the cost of raw materials and labour combined [70] | Invest in quality systems that can streamline quality practices and reduce costs | Medium | Introduce enterprise quality management software | |

| Ensure the management team has broad expertise to be leveraged across a portfolio of vaccines | |||||||

| Facilities and Equipment | Capitalised costs that depreciate over time Land Buildings Machinery Ongoing costs of upkeep Repairs Maintenance Utilities |

High fixed costs/design for minimising maintenance and utilities | 50–700 M US$ Example: It took Pfizer five years and 600 M US$ to build a manufacturing site in the US |

Design for very high facility utilisation. Limit the number of production platforms; force-fit new processes into established platforms to reduce the need for new facilities; increase utilisation of existing facilities. Use multi-dose vials. | High | Share filling lines across multiple vaccines when possible Shift production volumes to multi-dose vials to reduce filling costs (at the risk of higher vaccine wastage in the field). |

|

| Use single-use disposable systems to reduce capital cost | Medium | Reduced capital offset by higher operating (consumable) cost | |||||

| Minimise classified production space with closed systems and RABs. Limit automation and process/equipment Leverage blow-fill-seal filling technology to shrink cleanroom footprint and reduce final product component cost, and reduce labour [71] |

Low/medium | ||||||

| Utilise Contract Manufacturing Organisations (CMO) for low volume products or until demand supports facility construction. | Low/medium | Seasonal influenza vaccines produced at a CMO. Reduced capital offset by CMO contract fees. |

Table 3 focuses on the phases of product creation and validation. The vaccine production system reflects the vaccine manufacturer's substantial fixed and continuous maintenance costs. Manufacturers traditionally concentrate on determining the installed capacity to meet the unique market requirements for a particular production process [63]. This includes a thorough evaluation of business opportunities to evaluate the optimal capability and use. The additional fixed cost charge increases per unit dosage cost if the installed capacity is too large. In addition to the improper preparation, the industry could be disrupted by a further market segmentation by emerging innovations that alter the packaging and delivery of the vaccines. Table 3 also depicts the energy requirements and related CO2 emissions for each manufacturing process based on the current COVID-19 vaccine scenario.

2.5. Logistic and vaccine distribution

The cold chain logistics is one of its significant characteristics for COVID-19 vaccines. The general structure of the vaccine cold chain in routine immunisation programmes has been shown in Fig. 2. It has been recognised that prompt and effective distribution of COVID-19 vaccine worldwide, especially to all remote villages in developing countries that with low-income, could prevent more than 60% of subsequent deaths; however, if the high-income countries have the priorities, only around 33% of deaths would be avoided [72]. Cold chains worldwide, especially that across the developing world, would be highly reliant on.

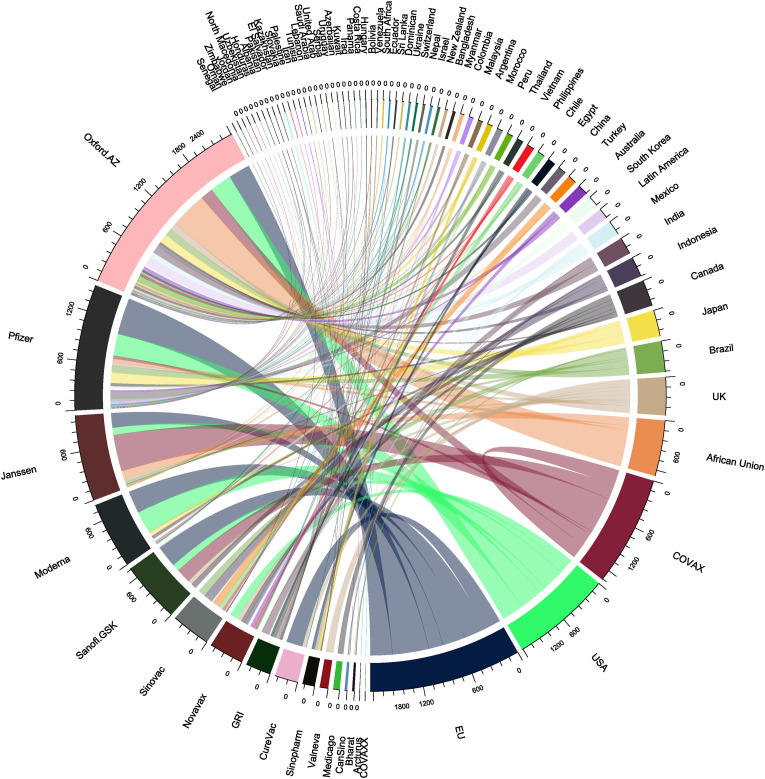

Fig. 5 shows the COVID-19 vaccine confirmed dose purchases by country/region/organisation. The data (as of April 2, 2021) were retrieved from the Duke Global Health Innovation Center [73]. It is noted that the data reflect the available information in the latest open-source dataset. The total vaccine purchases are 8.57 × 109 doses worldwide. The first five companies/organisations that offer vaccines are Oxford University/AstraZeneca (2.41 × 109 doses), Pfizer (1.52 × 109 doses), Janssen (1.04 × 109 doses), Moderna (8.03 × 108 doses), and Sanofi.GSK (7.32 × 108 doses). The largest buyers are the EU (1.84 × 109 doses), the USA (1.21 × 109 doses), COVAX (1.12 × 109 doses), African Union (6.70 × 108 doses), and the UK (4.57 × 108 doses). When more data are available, the flow information would be useful to quantitatively estimate the energy footprints related to the global logistics of COVID-19 vaccines.

Fig. 5.

Global flows (i.e. dose purchases) of COVID-19 vaccines (unit for the number in the circle figure: 1 × 106 doses). GRI = Gamaleya Research Institute. COVAX = COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access. The figure was designed and drawn by the authors. COVAX [74] is a global initiative to provide equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines.

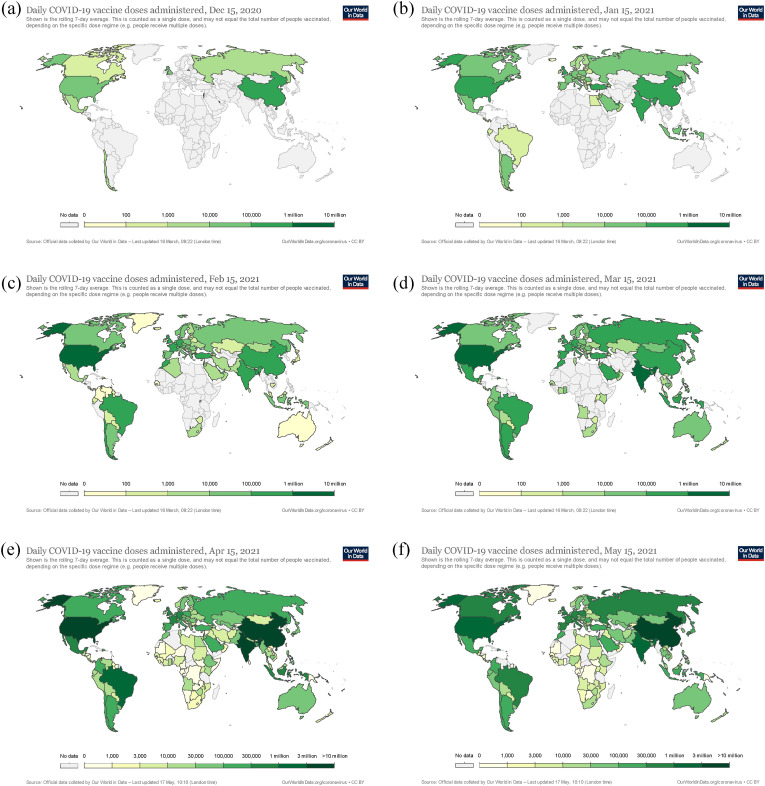

Fig. 6 shows the 7-day average trend and dynamics of global daily COVID-19 vaccine doses administered. On 15 December 2020, only a few countries, i.e. the US, the UK, Canada, China and the Russian Federation, started vaccination. However, on 15 March 2021, much progress on vaccination has been achieved, judged by the colours and coverage in Fig. 6(d). Many highly affected countries, including the USA, India and Brazil, have active vaccination by 15 March 2021. By 15 May 2021, the vaccination progress goes faster in Africa, Latin America and China. It is understandable that the progress with colour changes reflects the dynamics of energy consumption and emissions in different regions/countries. For the energy assessment, the energy demand will be reached later in the African region when the vaccination will be accelerated.

Fig. 6.

The trend of global daily COVID-19 vaccine doses administered (rolling 7-day average) from 15 December 2020 to 15 May 2021. Note: (a) 15 Dec 2020, (b) 15 Mar 2021, (c) 15 Mar 2021, (d) 15 Mar 2021, (e) 15 April 2021 and (f) 15 May 2021. The separate figures and data are retrieved from Our World in Data [75].

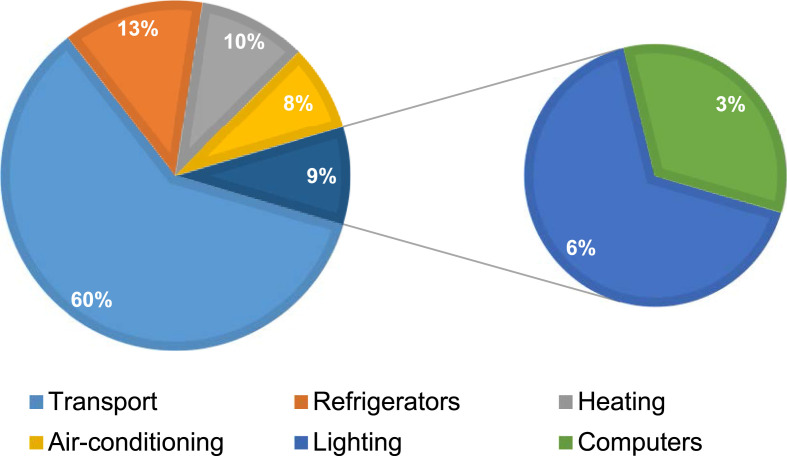

The energy and environmental impacts related to logistic and vaccine distribution are nonnegligible in terms of material resources to production places, production (clean) hall, packing – bottling, long transporting and storing at low temperature, distributing to the vaccination centres, disinfection and support material logistics, and logistic of human flows. One recent estimation indicated that cold chains represent ~1% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and are responsible for 3–3.5% of GHG emissions in developed countries [76]. Regarding the quantitative proportion of energy consumption share in the vaccine cold chains, as shown in Fig. 7 , Lloyd et al. [65] explored the way to optimise the energy efficiency for cold vaccine chain, taking Tunisia as a case, demonstrated that the transport sector consumes the most energy (accounting for 60%), followed by refrigerators (13%), heating (10%), air-conditioning (8%), Lighting (6%) and the computers (3%). The energy and emissions related to the logistic and vaccine distribution of COVID-19 vaccines are estimated in later sections.

Fig. 7.

Sector energy consumption share in the vaccine cold chain, adapted from Lloyd et al. [65].

2.6. Waste treatment and management

Although healthcare is prioritised during COVID-19 pandemics, waste treatment and management are also crucial. Klemeš et al. [11] analysed the surge of waste issues at the beginning of pandemics. Jiang et al. [17] overviewed the structural changes of global waste generation during pandemics. During the vaccination process, waste treatment and management in terms of vaccine waste collection, treatment, recycling, and energy recovery seem to be more challenging. The COVID-19 vaccine waste management expertise is urgently needed for vaccine manufacturers, regulatory agencies, and vaccine distributors. At the current stage, best practices on COVID-19 vaccine waste treatment should be promoted. Table 4 shows the practices from a medical waste company, Stericycle [77], which provides experiences for the treatment of syringes, vaccine packaging, empty vials, full or partial vials (also called residual doses), other medical waste and dry ice. It is noted that an autoclave process should be strictly performed to render the medical waste non-infectious before it goes to the waste-to-energy facility or is landfilled [78]. More environmental impacts of vaccine production are discussed in Section 4.1.

Table 4.

COVID-19 vaccination waste disposal best practices. Developed from Ref. [77].

| Waste type | Safe & compliant disposal guidance | Solutions | Energy required/potential energy recovered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Syringes | Used syringes shall be captured in sharps containers and disposed of as RMW. | SDS | |

| Vaccine Packaging | Can be disposed of as RMW. Follow manufacturer's instructions (e.g. returning) | RMW | |

| Empty Vials | All vial waste to be captured in sharps containers to mitigate potential diversion and illicit intent. Once placed in a sharps container, the container should be managed as RMW. |

SDS; NHPW | |

| Full or Partial Vials (Residual doses) | Once placed in a sharps container, these items should be managed as RMW or as NHPW. | RMW; NHPW | |

| Other Medical Waste | Gloves, gauze, cotton balls, bandages, and the like should not be placed in SDS. Either the regular waste or if potentially infectious material, disposed of as RMW. | RMW | |

| Leftover Vaccine | Local autoclaving [83]/incineration (most common approach [84]) | MBW, RMW or NHPW depends on the local regulation requirement | |

| Dry ice | Please refer to CDC guidance for the disposal of dry ice [85]. | CO2 | 0.14 kWh/kg [86] |

Note: RMW = Regulated Medical Waste; NHPW = Non-Hazardous Pharmaceutical Waste; SDS = Sharps Disposal Solutions; MBW = Microbiology and Biotechnology Waste. The other type of medical waste treatment has been summarised by Singh et al. [87].

3. Energy needs assessment

COVID-19 has been triggered a change in energy consumption pattern, shifting from one sector to another, at least under the current containment measures. There has been a decrease in air transport demand for passengers and a decrease in road transportation for commuting; however, there is an increase in energy demand for delivery services, residential, hospital, and specific industrial sectors. The overall net increment or decrement in energy demand results in subsequence environmental footprint is yet to be evaluated. However, energy efficiency is generally expected to be decreased due to the priority of staying safe and being responsive to an emergency. For instance, a lower occupancy (e.g., indoor area, plane, car) for social distancing and the use of disposable packaging for hygiene purposes are reducing energy efficiency. An increase in energy consumption of the medical-related sector, including the pharmaceutical industry and supply chain, is expected. According to the estimation from the DHL Express team [29], around 200,000 pallet transports and 15,000 flights are necessary to deliver around 1 × 1010 vaccine doses required over the long term. Additional flights are needed for other supplementary materials, including needles, syringes, disinfectants, and PPE.

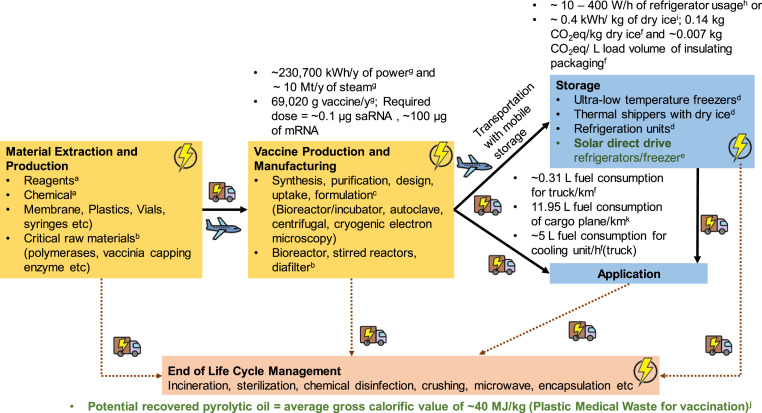

Different vaccine platforms related to the manufacturing processes, and importantly the sourcing and supply chain could contribute significantly to the differences in energy consumption. Fig. 8 shows the general life cycle of the ribonucleic acid (RNA) vaccine in the effort of mitigating the COVID-19 outbreak. The energy consumption source can be divided into 6 categories, including material extraction and production, vaccine production and manufacturing, storage, application, end of life management and transportation. Various materials are required in a vast amount to support the crushing need for vaccine development. The spurs of syringe (the USA alone required 8.50 × 108 related to vaccination campaign [88]) and vial production has been commonly reported [89]. Based on a previous study [90], the production of 1,000 glass vials requiring approximately 14 kWh of power and 243 MJ of natural gas, where the energy consumption of raw materials for cap and stopper, e.g. high-density polyethene, Aluminum, rubber and polyethene are not accounted. The shortage of critical raw materials such as polymerases (convert DNA to mRNA) and rare substances named vaccinia capping enzyme (preserve the mRNA from degrading) has also been reported [91]. Based on the study by Kis [92], 230,700 kWh of power/y is required to support the production of 69,020 g vaccine/y. The global demand for RNA vaccine was predicted as 1.56 × 1010 doses, containing 0.1 μg saRNA - 100 μg mRNA/dose [93].

Fig. 8.

The energy consumption along the vaccination life cycle. a [92], b [91], c [101], d [86], e [96], f [102], g [93], h [95], i [103], j [82], k [104], and mRNA and saRNA [105]. Energy consumption of waste treatment is summarised in Table 4.

In terms of stationary storage prior to application, refrigerators units are generally available in the hospital or laboratory for storing medicines, blood, samples (e.g., for COVID-19 testing) and vaccines. The cooling demand in hospitals is accounted for 365 Mt CO2eq/y, equivalent to the emission from 110 coal power plants [94]. The energy requirement of refrigerator usage is estimated at 10–400 W/h [95]. The energy consumption footprint can be differ/reduced by improving the insulation design and capturing waste cool to lower the ambient temperature [94] and the use of renewable energy (e.g., solar direct drive refrigerators and freezers [96]). The additional energy consumption is assumed to be relatively insignificant, mainly contributed by the ultra-low-temperature freezers. The expectation is particularly valid when compared to the cooling energy required in transporting (mobile). Among the most challenging and energy-consuming stages is the cold supply chain [97]. As mentioned in Table 2, most of the COVID-19 vaccines, regardless of type, are sensitive to the temperature where most of them need to be kept at a low temperature. Other than the special requirement on the refrigerated packaging method and distribution procedure, it needs to be transported via, for example, refrigerated trucks, refrigerated cargo ships or air cargo. This indicating the additional energy consumption on top of the fuel consumption to power the vehicle. For example, 5 L fuel consumption/h is needed for the refrigeration on top of the engine fuel consumption of 0.3 L/km by a truck, see Fig. 8. Alternative to refrigerated transport is dry ice, where the production consumes about 0.4 kWh/kg of dry ice (Fig. 8).

Waste is created along the vaccination life cycle, including the application stage. The common waste is consumables (syringes, needles, vials), PPE (both contaminated and non-contaminated), and packaging or shipping materials (plastics and cardboard/paper). Another waste source is vaccine wastage (closed vial wastage and open vial wastage [98]). Different wastage rate on COVID-19 vaccines has been reported from 0.3% to 30% [99]. The doses of vaccine (non-hazardous and does not contain viral material) could be handled as non-hazardous pharmaceuticals [83]. The waste handling approaches are summarised in Klemeš et al. [11], including both on-site, mobile and off-site options. Incineration is among the standard method. Considerate energy is consumed if autoclaving, chemical disinfection, microwave/radio-wave treatment and crushing/shredding are implemented. The energy consumption, especially the consumables and packaging, can be recovered if well segregated (or even more detailed classification). However, it is not well managed during this critical situation focusing on fighting the pandemic. For instance, Dash et al. [100] reported that pyrolytic oil with a gross calorific value of 42.24 MJ/kg could be recovered from the waste syringe. Som et al. [82] suggested an average of pyrolytic oil with a gross calorific value of 41.3 MJ/kg can be recovered from plastic medical waste; however, the logistic and the waste treatment should also be accounted for. The main energy consumption is expected to be the collection and transporting activities.

Despite the energy consumption along the vaccination life cycle, as summarised in Fig. 8 is identified, it is challenging to be quantified. The energy consumption is dependent on many factors, including the source of the materials, supply chain - destination, handling approaches and the type of operations, which is not well documented now. In the case of RNA based vaccine, a temperature below zero is required. Passive containers that are cooled by dry ice, e.g., thermal shipper by Pfizer - 15 d with re-icing every 5 d [106] for temporary during the transportation is preferable. The energy consumption for dry ice production is estimated at ~0.14 kWh/kg [103]. Weise [107] reported that 4,875 doses (equivalent to 975 vials) required 50 lbs (22.7 kg) of dry ice. One vaccine shipping box weight is ~80 lbs (36.3 kg). However, for air transportation, the vaccine shipping in passive containers is limited by the weight of permitted dry ice rather than the total weight, as at reduced pressure, the sublimation rate of dry ice would increase with the potential risk of high levels of CO2 gas in compartments [108]. During this critical period, the limitation has been exceptionally relaxed (i.e., 3,300 kg to 11,000 kg) [109], where 52 containers of vaccines are permitted (e.g., for Boeing 747 cargo plane). The use of a built-in cooling unit or dry ice with a truck will contribute to a different energy consumption level.

A rough estimation is performed, using the Czech Republic as the reference. The estimated energy consumption is according to the 709,750 doses received in the country (9,750 doses in Dec 2020, 700,000 doses in March 2021). This consists of only 3% of the needed doses, considering 10.65 × 106 of the population. It should be noted that the calculation is subjected to a set of assumptions mainly to highlight the potential stages for energy reduction measures in a relatively quantitative manner. Three scenarios are considered for transportation stages, including from Kalamazoo site (the USA), Puurs site (Belgium), and Karlsruhe site (Germany). The summarised estimation (Table 5 ) shows that the main energy consumption lies at the cold supply chain, where the magnitude is significantly larger. The calculation results indicate that almost 99% of the energy consumption is by the supply chain. This is especially the fuel consumption of air cargo travelling from the USA (Kalamazoo) to the Czech Republic. If a different scenario is applied, assuming from Germany (Karlsruhe) to the Czech Republic, the share of energy consumption by the cold supply chain is 92% (by air cargo) and 26% (by truck). For the scenario of the Puurs site, the share of energy consumption by the cold supply chain is 95% (by air cargo) and 37% (by truck). Material production and extraction consume considerable energy, where several other materials are yet to be considered. Although the estimation can draw no conclusive output, it highlights the supply chain's critical role in energy reduction. The energy consumption in the material production stage can be mitigated through material recovery, and it has been advancing. However, supply chain stages required a considerate effort in identifying a sustainable network design, considering different factors, especially the reliability and urgent need. Santos et al. [110] recently suggested that the RNA-types vaccine has the lowest energy efficiency compared to the other vaccines for COVID-19. A supply chain model that minimises energy consumption and could be responsive to emergency arrangements deserves more research attention.

Table 5.

Estimated energy consumption for RNA-type vaccines – Example scenarios of the Czech Republic.

| Stages | Conversion factor (as summarised in Fig. 8) | Estimated energy consumption (for 709,750 doses) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Vaccine (RNA) 1st batch = 9,750 doses [111] 2nd batch = 700,000 doses [112] | ||

| Production and manufacturing | ||

Material production and extraction

|

|

|

| Vaccine manufacturing |

Other Assumptions:

|

|

| Cold Supply Chain (energy consumption embedded by packaging is excluded) Sum for “from Kalamazoo” = ~6.0 × 106 MJ Sum for “from Karlsruhe (air cargo)” = 4.9 × 105 MJ Sum for “from Karlsruhe (road transport)” = 1.5 × 104 MJ Sum for “from Puurs (air cargo)” = 7.6 × 105 MJ Sum for “from Puurs (road transport)” = 2.5 × 104 MJ | ||

| Dry ice during transportation |

|

|

| Fuel consumption (Air Cargo) |

|

|

| Fuel consumption (Refrigerated Lorry) |

Other Assumptions [111]:

|

|

| End of the life cycle | ||

| Waste management |

|

|

4. Environmental impacts

The production, transportation and waste disposal of vaccines consume resources and cause environmental pollution. The priority development and implementation of vaccination at a large scale in the whole world overwhelm the situation. This section assesses environmental footprints related to vaccination and offers suggestions for mitigating/reducing environmental footprints.

4.1. Environmental impact of vaccine production

Environmental awareness in different types of countries has significant heterogenicity. The developed countries managed it well. However, according to a recent survey [117] for emerging country manufacturers in Brazil, South Africa, India, the Republic of Korea and China, so far, only about 50% of respondents have specific strategies to minimise the impact of vaccines on the environment. Although 73% of respondents have shown interest in pursuing reducing the environmental impact, only about 25% of respondents utilise biodegradable/recyclable packing [117].

After consulting with the technologist of the biological technology enterprise which produces Sputnik V vaccines, all enterprises of a similar profile in the Russian Federation operate under the standard rules and have similar requirements. The production of vaccines at the enterprises of the Russian Federation is carried out following the Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) rules [118], which was also introduced by Lu [119]. The GMP rules regulate, among other things, the requirements for the release of pollutants into the environment. Environmental pollution during the production process for applied technology is insignificant.

The production of a vaccine is a highly efficient biotechnological production. It is low in energy consumption, which makes it possible to reduce the amount of waste significantly, whilst the natural resources themselves are consumed in an insignificant amount. Environmental problems related to vaccination mainly include two aspects: (i) the destruction of solid waste (producer biomass) and (ii) the treatment of liquid waste (waste liquid). They are detailed as follows:

-

(i)

The destruction of solid (and especially toxic) waste. The most primitive way to dispose of mycelium after it has dried is to take it to city dumps. Another method is that the mycelium is placed in-ground pits on a concrete floor, mixed with soil and left for several years (composting is not a cost-effective method). There should be two promising disposal routes for solid waste. The first is the sterilisation of mycelium with its subsequent addition to feeding for farm animals, building materials. The second is the extraction of various fractions from mycelium, for example, lipid, and its use as a detergent instead of a deficient component (whale oil) or synthetic defoamers.

-

(ii)

Regarding the liquid waste treatment, including wastewater. Liquid waste is a culture liquid after the mycelium is separated from it and the target product is extracted. Liquid waste treatment is a system consisting of several successive units: the first settling tank with suction and an aeration tank - a reinforced concrete pool with air supply through pipes in its lower part. Air passes through the entire thickness of the liquid, saturates it with oxygen, which contributes to the intensive course of oxidative processes. Another potential pathway lies in the use of mycelial waste as components of nutrient media for microorganisms with preliminary treatment by enzymatic hydrolysis.

4.2. Emissions created during the transportation of vaccines

The big challenge is the huge demand for vaccines and vials of COVID-19 vaccination and related demand for syringes and disinfection material. For example, only the Pfizer company planned to produce and deliver 1.20 × 109 doses of vaccines by the end of 2021, which is the largest vaccination programme in Pfizer's history [120]. Pfizer expected to load the temperature-controlled packaging boxes with roughly 7.60 × 106 doses using 24 trucks and 20 flights every day [121]. The logistics and transportation would result in apparent environmental impacts. The emissions produced by the cold supply chains via aircraft, ships, and transportation tools on the land are understandable to be massive. For instance, the Boeing 747 Jumbo Jet burns about 10–11 t of fuel/h when flying on the cruise, which means a total of ~70 t of fuel from London to New York [122]. In addition, a Boeing 747 uses about 7.84 t of fuel for the process of take-off, climbing and descending [123]. Based on the statistical data regarding the average number of departures per aircraft per day, the average number of flight hours per aircraft per day, and the average number of aircraft in service from 2007 to 2012 [124], the average number of commercial flight hours per trip of Boeing 747 is estimated as 4.02 h. Since the actual data would be available at least several months later, the average 4.02 h is assumed to be the flight time of aircraft with COVID-19 vaccines. That means a Boeing 747 cargo aircraft carrying one cargo load of COVID-19 vaccines would consume about 48.0–52.0 t of fuel (coal oil). The International Air Transport Association (IATA) estimated that 8,000 fully loaded Boeing 747 aircraft would be needed if each of 7.80 × 109 people worldwide would take a single dose of COVID-19 vaccine [125]. However, according to Table 2, two doses are reasonable for each person in reality, which means a total of 16,000 fully loaded Boeing 747 aircraft. The total fuel consumption would be 768–832 kt. According to the transformation of CO2 emission and fuel burning (i.e. about 33 t of CO2 for 10.7 t of fuel) [123], the total CO2 emission related to the COVID-19 vaccine flight would be over 2.38–2.57 Mt. It is noted that the CO2 emission of flights corresponds to 2% of global human-induced CO2 emissions and that the total amount 915 Mt CO2 was produced by global flights [126]. It is apparent that the vaccination-related emission is significant from the air transportation perspective. However, air transportation and emission are unavoidable to guarantee vaccine accessibility. In addition, the cargo plane emissions are just part of the total emissions in the logistic system, as shown in Fig. 2. More assessments regarding shipments and land transportation are required when data are available.

In addition to the main allocation and distribution from the manufacturers to the airports and vaccine central/local stores, the last-mile distribution starting from the local stores is also important. The environmental impact of the last-mile distribution would be significant due to bulk transportation and packing efforts. In Paris, bike delivery was creatively adopted by some hospitals to reduce the carbon footprints of the last mile distribution [127]. If the vaccine quality can be guaranteed when using the bike delivery, it could be a promising way to reduce the environmental impact as cycling generates 16 g of CO2/km only, but that would be on average 101 g of CO2/km by busses and 271 g of CO2/km by private car [128]. However, cycling delivery is a limited option for vaccines requiring low temperature and refrigeration treatment. The environmental impacts of various vaccine options in the refrigeration stage have been quantified by Santos et al. [110], where an index ─ namely, Total Equivalent Warming Impact ─ is suggested as a tool for decision making in the second round of immunisation. The assessment for Brazil suggested that cold storage of Oxford-AstraZeneca, Janssen and CoronaVac vaccines generates 35 times less environmental impact than the Pfizer option.

Although the COVID-19 curbed global carbon emissions last year, the reduction rate, i.e. 6.4%, is not much as expected [129]. Jiang et al. [4] drawn two energy-consumption curves. One is for a COVID-19 energy curve (without considering extra energy consumption), and another one for an extra energy curve. Such curves could partially explain why the global annual carbon emissions in 2020 are not much as expected. The extra energy consumption for PPE, disinfection and supply chains [14] would likely remain in 2021. Klemeš et al. [14] estimated that the energy demand for ethanol production used for disinfection might be up to 181 PJ in 2020, with a 12.3% increase compared to 2019. The vaccination-related disinfection would enlarge the energy demand and emissions in the following years. Consequently, the extra energy consumption related to vaccination would enlarge the effects of the extra energy consumption curve in the following year. Let alone, the rebound effects in carbon emissions could be certain in 2021 due to the lift of the temporary and non-structural reforms and the recovery of economic activities [130].

4.3. Environmental pollution of post-vaccination waste

This section emphasises the environmental impact of post-vaccination waste, which can be considered and create health problems if not taken appropriately. Beyond the waste during the production process, as introduced in Section 4.1, the main waste related to vaccination would come from (i) vials, syringes and needles, (ii) outdated/expired vaccines and (iii) packaging with single-use plastics. They are detailed as follows.

The massive waste of vials and syringes poses potentially great problems for environmental sustainability [127]. In the healthcare sector, about 85% of medical waste is non-hazardous solid waste. Glass vials and plastic syringes after extracting the vaccines could be recycled if they have been collected, disinfected and stored properly [127]. However, this is not that much popular in the EU as more than 50% of respondents mentioned incineration of hospital waste, and about 60% of respondents reported that recycling firms refuse to recycle hospital waste [131]. The possible consideration might be that glass vials and needles with vaccines should be handled by special containers and that they are harder to be recycled in remote areas due to less developed disposal service [132].

The outdated/expired vaccines should be handled carefully since special disposal methods are required for large quantities of vaccines, which has been introduced by the guidance to waste vaccines [133]. Different states have strict regulations on the disposal of outdated/expired vaccines. For example, under a producer's vaccine return policy, the nonviable, unused or outdated vaccines should be returned to the manufacturers for credit [134].

The single-use plastics, including the massive PPE (i.e. masks, gloves, respirators, protective suits, shields and goggles), have been overwhelmed the waste management system in the pandemics Stage I [11]. Before vaccine campaigns, the issues have been surging. For example, the medical waste with a large proportion of plastics increased 370% in Hubei, China, by March 11, 2020 [11]. More details about the challenges and suggestions about the surging of plastics waste during the pandemics Stage I are referred to as the pandemic repercussions on the management of plastics [135] and the plastic waste footprint and circularity [136]. Regarding the single-use plastic materials used for vaccines and packing, some commissions may argue that the potential increase in waste from the vaccination campaign would be not significant by considering that the economy has slowed and the overall plastic consumption has been reduced [127]. However, this could not be a strong reason considering (1) the severe impact of medical plastic waste has been widely reported in 2020 [137] and (2) the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) were hindered by the COVID-19 pandemics severely [138].

4.4. Suggestions for mitigating/reducing the environmental footprints

As discussed in Sections 1, 2, 3, 4.3, the environmental footprints have heterogenicity in different processes of vaccination. Compared to vaccine production, major footprints are produced by cold-chain logistics and post-vaccination waste. Zaffran et al. [139] overviewed the issues in supply and logistics systems of vaccines and emphasised that, in immunisation systems, the environment-related impacts of materials, energy, and processes should be minimised. The suggestions for mitigating the environmental footprints are detailed as follows.

-

•

Energy (possible renewable) for refrigeration: The energy accessibility is relatively low in some remote areas without access to the power grid or with only intermittent/limited electricity supply. However, the cold-chain logistics are strict for COVID-19 vaccines, such as vaccine storage at a temperature of 2–8 °C or even at −20 °C and −70 °C. One of the solutions relies on distributed energy systems and renewable energy, like solar energy and wind energy [140]. For example, to promoting end-to-end delivery of cold chain products, including temperature-sensitive vaccines, the UNICEF has assisted in installing more than 40,000 solar-powered cold-chain fridges since 2017, mostly in the Africa region [141]. However, the potential challenge lies in the quality of solar irradiation in remote areas as well as the energy supply outside the availability of solar irradiation. The UNICEF supply division has stated the requirement of solar irradiation per day, i.e. more than 3.5 kWh/m2, as the criterion for choosing solar-powered systems for the safe storage of vaccines. For those remote areas that do not meet such conditions, mobile energy storage devices should be prepared to promote vaccination, which improves vaccine equality significantly, however, increases energy and related emissions.

-

•

Cold supply chain optimisation: The packaging, supply chain and environmental pollution have been discussed broadly [142]. There are always trade-offs between environmental sustainability and vaccination efficiency in the cold supply chain of COVID-19 vaccines. For example, more local centres could reduce the total energy consumption and carbon emissions caused by the massive movements to make to get vaccinated from the individual patients' perspective; however, the distribution workload and energy usage related to vaccines to multiple centres would be elevated significantly, and the requirements for low-temperature storage get more challenging by designing more vaccine centres [127]. This is a multi-objective optimisation problem in the cold chain logistics, which considers the environmental impact, vaccination efficiency, the quality of vaccine storage, and even the number of outdated vaccines. A suitable optimisation method with endowed weights from decision-makers could provide a balance to the whole problem. It is noted that more weight could be endowed to vaccination-related objectives considering the crucial period of pandemic control. The weights could also be adjusted with the development of the vaccination to reduce the environmental footprints.

-

•

Some other suggestions related to the Circular Economy strategy and the lower GHG emission strategy are referred to as Section 5.2.

5. Lessons and opportunities for future pandemics

The most important issues under a crisis or a public event are possible lessons that could be used to guide future risk prevention and responses. It is also meaningful to figure out potential opportunities for future pandemics.

5.1. Lessons learned at the initial stage of vaccination

Although COVID-19 could have vaccines to heal, it is challenging to find “vaccines” for climate change [143]. Potentially the worst lesson in the energy and environmental field could be that the vaccination for coping with COVID-19 would further exacerbate climate change by increasing environmental (GHG, NOx, SOx, water, etc.) footprints [144]. Regarding the supply chain operations during vaccine campaigns, decision-makers of the COVID-19 vaccine delivery systems have to investigate evidence-based delivery strategies which focus on demand planning, vaccine allocation and distribution, and vaccine coverage checking to achieve better performance [145]. In terms of the packing of vaccines, different companies have their temperature-controlled solutions [120]. However, the responsible selection of materials with lower GHG emissions is crucial, considering that the COVID-19 pandemics and vaccination campaigns may last several and even be repeated for years. There are many lessons learned in the current phase. This study emphasises the potential wastage of vaccines since the wastage reduction of COVID-19 vaccines could be an important pathway to reduce the energy and environmental footprints related to vaccines indirectly.

The wastage of vaccines is quite common worldwide, as reported up to 50% wastage rate for regular vaccines globally every year [146]. Recent estimations indicated that at least 25% of vaccines might be wasted globally due to logistics and temperature control failures [147]. During this crucial period, the wastage rate of COVID-19 vaccines should be minimised. For example, the allowable wastage of COVID-19 vaccines was assumed at 10% in India [148]. However, about US$ 3.41 × 1010 would lose annually even if only a 10% wastage rate has been achieved, without counting the financial and physical costs [147]. The strict compliance of the wastage limit could assist in the accurate order planning for vaccines. The wastage covers two types, i.e. unavoidable wastage and unnecessary vaccine wastage [98]. From the perspective of historical experience, the stabilisation of vaccination relies on shelf-life, storage temperature and in-use stability [28]. The preventable wastage of COVID-19 vaccines may occur at different stages, mentioning at least a few:

-

(i)

The massive purchase orders in the planning stage: Vaccine acceptance in different regions present heterogeneity [25]. The massive orders without an accurate estimation of the vaccine acceptance in a specific country would have a high probability to result in wastage.

-

(ii)

The allocation strategies supply chain: The allocation models in regular supply chain problems are not necessarily suitable for new situations. That is why Zenk [149] appealed to the redesign of the allocation models to distribute the COVID-19 vaccines.

-

(iii)

The storage facilities and conditions: Those mRNA vaccines have strict requirements about low-temperature transport and cold storage conditions. For example, a 25–30% wastage rate of BioNTech/Pfizer vaccines already occurred at some places due to logistical constraints in the cold supply chain [150].

-

(iv)

The design of syringes: The syringes given by the federal government could only extract 5 doses from vials from Pfizer's coronavirus vaccine [151]. However, pharmacists have claimed that each vial could provide 6 or even 7 doses if extracting correctly [152]. According to such a fact, at least 16.7% of vaccines were going to waste due to the design of syringes.

-

(v)

The number of doses in each vial [99]: WHO calculated the wastage rates for a single dose, 2 or 5-dose, and 10 or 20-dose were 5%, 10%, and 25% if the opened vial can be stored and reused in later sessions [98]. This has also been partially verified by Indian situations [153].

-

(vi)

The no-show behaviour of the population [154]: Although some residents signed up for vaccination, not all of them would show up to get vaccines due to multiple reasons. Such population behaviour could increase the wastage rate as the vaccines have to be used in a suitable time window.

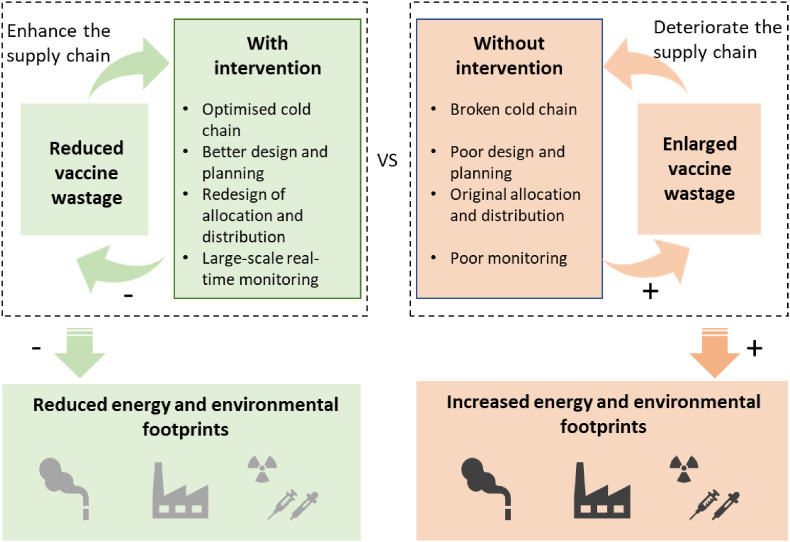

With proper intervention in the cold chain management, less wastage of vaccines would be created, as well as the energy and environmental footprints. On the contrary, the wastage and footprints could be enlarged if nothing is done in terms of cold chain optimisation, design and planning, allocation and distribution modes, and real-time monitoring and tracking. Fig. 9 shows the comparison between cold chains with intervention and without intervention. For these possible pathways related to wastage, some strategies/methods to reduce the wastage of COVID-19 vaccines are highlighted as follows:

-

a.

Optimise cold chains and improve their resilience. Before the vaccination campaign, the global supply chains have already been observed a lack of resilience [155]. The United Nations Environment Programme estimated that the broken cold-chain logistics and the lack of temperature control could waste 1 × 109 vaccines [146], which not only causes at least US$ 1 × 1010 cost (about US$ 10 a vaccine as non-profit) but also increases the workload in the cold supply chains. Proactive resilience analytics of the supply chain models for vaccination could promote achieving the goals of vaccination programs [156].

-

b.

Better design and planning to reduce possible waste. The design of syringes and dosage could save vaccines directly. The vaccination planning (store centres, logistics and management) should not be prepared at the last minute as there are possible future pandemics. The price of vaccines, the public's vaccination intention, and policies would influence the demand for COVID-19 vaccines [157]. Over storage would also be a planning strategy. However, some of the over-stored vaccines in a single country would increase the wastage rate as the viruses have multiple variants. One of the promising solutions is that the non-governmental organisation, COVAX, has prepared for approximately 2 × 109 doses of vaccines for global vaccination [158], which improves vaccine accessibility by vaccine sharing.

-

c.

Dynamic change mechanism regarding vaccine allocation and distribution. Although the governments have some experience with massive vaccine allocation and distribution, the global COVID-19 delivering with a much greater scale is the first time [159]. With the rapid development of pandemics and the vaccination process, a dynamic change mechanism could be beneficial. For example, to motivate the vaccination, the USA government allocated more vaccines to those states that administer more shots efficiently [160]. The vaccine distribution strategies should also be adjusted based on distinct objectives, e.g. saving the most population, focusing on the groups at greater risk, and guaranteeing societal benefits [161]. If the situations have to deal with tight resource constraints, process integration technologies that incorporate mathematical programming would be a favourable option [162].

-

d.

The large-scale real-time monitoring of vaccination and real-world geospatial visualisation [163] is required to reduce information asymmetry amongst organisations and companies. Bloomberg [8] has set up a well-known COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker to visualise the global vaccination situations, which also calculated that more than 1.24 × 108 shots were given by 6 February 2021. From the perspective of technologies, the decentralised and immutable databases offered by blockchain would be a proper tool to assist stakeholders in cooperation [164]. More details regarding the applications of the Internet of Things (IoT) [165] and blockchain for vaccine supply chains are referred to as the intelligent blockchain-based system [166] and the blockchain platform for COVID-19 vaccine supply management [167].

Fig. 9.

The comparison (wastage and footprints) between cold chains with intervention and without intervention.

5.2. In time contingency planning to mitigate the energy demand for possible future pandemics

The pandemic of this global scale caught humankind substantially unprepared. This can be a little surprise as many countries have been substantially spending on defence precautions, and pandemics could produce efficient weapons of mass distractions. Noronha [168] emphasised that the COVID-19 vaccination campaigns could be a starting point for the development of future two-decade cold chains. Rele [169] briefly summarised the opportunities and impacts of COVID-19 vaccine development on future emerging infectious diseases. However, the main topics of this manuscript are energy and related emissions, and let us focus on them. In this field, preparing the contingency plans to avoid extra energy needed for emergency supplies: production, logistics, management, waste treatment, etc., is crucial. The main issue for planning is an assessment, e.g. how likely similar pandemics are going to occur and what the frequency could be. Making comprehensive preparations would consume substantial funding, which may be used, but also could be idle during its “best before” life span.

From the point of energy and emission, the first phase of the vaccination was lucky to be performed during substantial lockdowns, when was a sufficient about of energy available for an extra demand. In some cases, it was even welcome to boost, e.g. haulage business, suffering by lack of demand, both due to substantially reduced travel as well as consumption. As it can be expected that the vaccination is going to be a long-term exercise and can overlap with the period of the economic recovery, the increased demand can create unwanted peaks in both energy demand and consequently in emissions and pollution generation.

However, vaccination has just started, and a number of issues have been still open:

-

(i)

For how long the vaccines are going to provide the immunity, which means how frequently the vaccination should be repeated?

-

(ii)

How efficient are going to be vaccines against the COVID-19 mutations and new strains?

-

(iii)

Is it going to work the herd immunity?

-

(iv)

How long will it take to meet the needs worldwide, especially for the developing countries, which means when the world would be back to the normal?

For economic reasons, the priority should receive backup production capacities, which can be fast modified for the production of pandemics fighting necessities and especially new vaccines.

A promising option would be variant-proof vaccines [170]. It is a very interesting idea in the imminent term to deal with fast appearing variants, however in the longer-term "PAN-VIRUS VACCINES". If successfully prepared, they should be neutralising antibodies to block only specific viruses. Broadly neutralising antibodies stop infection by many related viruses. Vaccines that elicited such broad antibodies would protect against multiple strains of each virus, be that influenza or Ebola.

The European Commission [171] has been developing commission staff working document energy security: Good practices to address pandemic risks, presenting “GOOD PRACTICES” at a glance:

-

•

Preserving supply to vulnerable customers

-

•

Declaring the energy sector as an essential service

-

•

Preserving free movement for specialised energy workers

-

•

Preserving essential transport flows moving to ensure energy supply chains

-

•

Well-functioning of the internal energy market

-

•

Strong risk preparedness plans

-

•

Strong business continuity and contingency plans

-

•

Solidarity and cross-border coordination, communication and information sharing

-

•

Teleworking for non-shift activities and non-core activities

-

•

Rescheduling non-essential maintenance works

-

•

Hygiene and sanitary measures, as well as training on hygiene protocols

-

•

Cross border assistance, cooperation and training for operators

-

•

Redundancy of control rooms and implementation of remote control

-

•

Establishing base camps and reserves of volunteers for critical infrastructure

-

•

Reduction of the regular exchange of personal activities

-

•

Pre-confinement of staffs before accessing isolated locations,

-

•

In key locations, early detection, evacuation measures, and specific support to workers

-

•

Reinforcing cybersecurity measures and cooperation

-

•

Adopting pragmatic risk-based approach by national regulators, in particular, the nuclear sector

-

•

Paying attention to the economic impact on energy companies, subcontractors and investors

Those good practices have been obviously advisable; however, the real-life situation in the heat of pandemics demonstrated that not all of them are feasible to be achieved. Besides that, the vaccinations were not included, and the energy demand to follow some of them can be substantial and acceptable for crisis management only.

WHO prepared several contingency planning documents, e.g. for flooding [172], several documents were presented for the influenza pandemic, e.g. dealing with the vaccination [173]. However, they did not consider the consequences of energy usage and emissions. They are still many lessons to be learned in the energy field and summarise the planning and preparedness for future pandemics.

5.2.1. Circular Economy strategy