Abstract

Background

There is strong evidence that portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT) is associated with poor survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, data regarding the clinical significance of hepatic vein tumor thrombosis (HVTT) is rare, particularly in Western patients.

Objective

To determine the HVTT prevalence in a Western patient population and its impact on survival.

Methods

We included 1310 patients with HCC treated in our tertiary referral center between January 2005 and December 2016. HVTT and PVTT were diagnosed with contrast‐enhanced cross‐sectional imaging. Overall survival (OS) was calculated starting from the initial HCC diagnosis, and in a second step, starting from the first appearance of vascular invasion.

Results

We observed macrovascular invasion (MVI) in 519 patients who suffered from either isolated HVTT (n = 40), isolated PVTT (n = 352), or both combined (HVTT + PVTT) (n = 127). Calculated from the initial HCC diagnosis, the median OS for patients with isolated HVTT was significantly shorter than that of patients without MVI (13.3 vs. 32.5 months, p < 0.001). Calculated from the first appearance of MVI, the median OS was similar among patients with isolated HVTT (6.5 months), isolated PVTT (5 months), and HVTT + PVTT (5 months). Multivariate analysis confirmed HVTT as an independent risk factor for poor survival.

Conclusions

HVTT may be more common than typically reported. In most patients, it was accompanied by PVTT. Isolated HVTT occurred less frequently and later than isolated PVTT; however, once developed, it had the same deleterious impact on survival. Therefore, patients with HVTT should be classified as advanced stage of HCC.

Keywords: hepatic vein thrombosis, hepatic veins, hepatocellular carcinoma, survival, tumor, tumor thrombosis

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies worldwide and one of the leading causes of cancer‐related deaths. 1 HCC has a strong tendency for macrovascular invasion (MVI), which was reported to occur in up to 70% of an autopsy series 2 and around 20% of a surgical series. 3 Portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT) is the most common form of vascular invasion. PVTT was found to be a strong negative predictor of survival in several studies and meta‐analyses. 4 , 5 , 6 Hepatic vein tumor thrombosis (HVTT) appears to occur less frequently, and the clinical significance is unclear. Data published on the outcome of patients with HVTT are relatively scarce and almost exclusively based on Asian patient cohorts. Moreover, most of those studies were limited to a specific treatment, such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), 7 ablation, 8 or resection. 9 To our knowledge, no single study has specifically focused on HVTT among patients in Western countries. Guidelines by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) 10 and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, 11 do not comment on HVTT, and it is not explicitly mentioned in the current version of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system. Hence, there is currently no formal guidance on how to classify patients with HVTT.

The present study aimed to analyze the prevalence of HVTT and its impact on survival in a Western patient population.

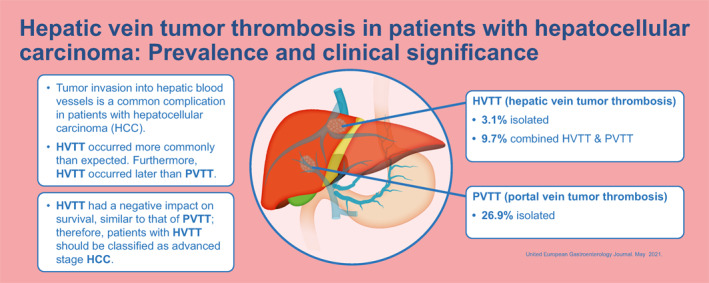

Key Summary.

Current knowledge

Tumor invasion into hepatic blood vessels is a common complication in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Although several studies have shown the negative impact of tumor invasion into the portal venous system (PVTT), the data are quite limited on the impact of tumor invasion into the hepatic veins (HVTT), particularly for Western patients.

What are the new findings?

In summary, we found that HVTT occurred more commonly than expected. Furthermore, HVTT occurred later than PVTT.

Nevertheless, once developed, HVTT had a negative impact on survival, similar to that of PVTT; therefore, patients with HVTT should be classified as advanced stage HCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient recruitment

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the responsible ethical body (Ethics Committee of the Medical Association of Rhineland Palatinate, Mainz, Germany). Informed consent was not required, given the retrospective study design. Patient records and clinical information were anonymized and deidentified prior to analysis. Treatment‐related data, including survival of all consecutive patients with HCC were retrieved from a prospectively populated clinical database, installed in 1998 at our university medical center. 12 HCC diagnoses were based on biopsy or imaging analyses, according to the EASL guideline. 10 For this study, we restricted our evaluations to all consecutive patients treated from January 2005 to December 2016. Patients treated earlier than 2005 sometimes had incomplete data. Because PVTT was previously identified as a major risk factor in this cohort, 6 we compared survival among four subgroups classified according to their MVI status, as follows: no MVI, isolated HVTT, isolated PVTT, and HVTT combined with PVTT (HVTT + PVTT).

Imaging analysis

MVI was diagnosed by consensus between two board‐certified radiologists with more than 10 years of experience in HCC‐imaging (S. S. and R. K.), who re‐evaluated all available contrast‐enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies. Differentiation between a bland thrombus and a tumor thrombus was performed with established criteria for CT and MRI. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 The time of first appearance and the extent of MVI were documented. PVTT was classified according to the classification suggested by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan: Vp0 = no PVTT, Vp1 = segmental portal vein invasion, Vp2 = right anterior/posterior portal vein, Vp3 = right/left portal vein, and Vp4 = main trunk (Figure S1). 3 , 17 HVTT was classified according to the classification by Chen et al. 18 : type I = tumor thrombosis involving hepatic vein, including microvascular invasion, type II = tumor thrombosis involving the retrohepatic segment of the inferior vena cava; and type III = tumor thrombosis involving the supradiaphragmatic segment of the inferior vena cava (Figure S2).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as the median and range; categorical data are expressed as percentages. χ 2 tests of independence and Mann–Whitney U tests were performed to compare distributions between groups. Overall survival (OS) was calculated for each group, and Kaplan–Meier survival curves and log rank tests were performed for comparisons.

Because a significant proportion of patients developed MVIs during the observation period, in a second step, we conducted an additional survival analysis, beginning at the time of first appearance of HVTT or PVTT. Therefore, OS was defined as either the time between the HCC diagnosis and death/last follow‐up or as the time between MVI appearance until death/last follow‐up. Patients lost to follow‐up were censored at the time of last contact.

Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to determine the influence of HVTT as an independent risk factor. Previously established risk factors, including alpha‐fetoprotein (AFP), tumor number and size, and albumin‐bilirubin grade (ALBI grade), 6 were included in a multivariate regression analysis. In some cases, data were missing on AFP levels and ALBI grade; therefore, the Cox regression analyses were restricted to the 1107 patients with complete data.

Statistical analyses were performed with R 3.5.3 (A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.R‐project.org; last accessed 2019). Log rank tests and Kaplan–Meier curves were performed to compare survival between different patient strata (packages “survival” and “survminer”).

This analysis had an exploratory intention; therefore, p values should be interpreted in a descriptive manner. According to convention, results were considered significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Patient and tumor characteristics

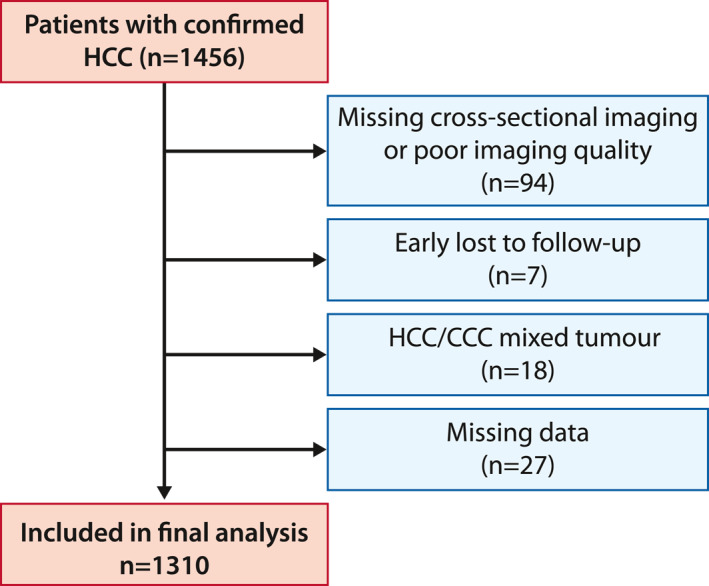

In total, 1456 patients with proven HCC were treated between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2016. Follow‐up ended on 30 June 2018. After a complete workup, 146 patients were excluded, due to various reasons (Figure 1). Therefore, the final analysis included 1310 patients.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram showing the reasons for dropping out of the study and the final number of patients included in the analysis. CCC, cholangiocellular carcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma

HVTT was diagnosed in 167 patients (12.7%). Among these patients, 127 (9.7%) had HVTT + PVTT and 40 (3.1%) had isolated HVTT. In contrast, isolated PVTT was found in 352 patients (26.9%). A total of 791 patients (60.4%) showed no MVI during the observation period.

In a significant proportion of patients with PVTT (37.2%) or HVTT (54.5%, p < 0.001), MVI was not existent at the initial tumor diagnosis, but developed during the observation period. In patients that developed MVI after the initial tumor diagnosis, the median time interval until first MVI appearance was significantly different between the PVTT (95 days, range: 15–1980) and HVTT (387 days, range: 35–1935, p = 0.006) groups. Detailed demographic data at time of initial diagnosis of HCC are provided in Table 1. We further added a second table (Table S1) providing the pertinent parameters at time of first MVI into the supplement.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma at time of initial HCC diagnosis

| Variable | No infiltration | Isolated HVTT | Isolated PVTT | PVTT + HVTT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number, n (%) | 791 (60.4) | 40 (3.1) | 352 (26.9) | 127 (9.7) |

| Median age, years (IQR) | 66.3 (59.5–72.7) | 66.2 (59.8–75.2) | 66.7 (59–73.1) | 65.6 (58.8–72.6) |

| Males, n (%) | 634 (80.2) | 35 (87.5) | 288 (81.8) | 107 (84.3) |

| Females, n (%) | 157 (19.8) | 5 (12.5) | 64 (18.2) | 20 (15.7) |

| Etiology, a n (%) | ||||

| Alcoholic | 329 (41.6) | 17 (42.5) | 174 (49.4) | 56 (44.1) |

| Hepatitis C | 199 (25.2) | 4 (10.0) | 78 (22.2) | 23 (18.1) |

| Hepatitis B | 72 (9.1) | 6 (15.0) | 34 (9.7) | 19 (15.0) |

| Hepatitis D | 9 (1.1) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| NASH | 51 (6.4) | 3 (7.5) | 23 (6.5) | 5 (3.9) |

| Hemochromatosis | 26 (3.3) | 3 (7.5) | 7 (2.0) | 2 (1.6) |

| Antitrypsin deficiency | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AIH | 6 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PBC | 11 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.8) |

| PSC | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| Unknown/other | 145 (18.3) | 13 (32.5) | 48 (13.6) | 33 (26.0) |

| ALBI score, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 118 (14.9) | 6 (15.0) | 22 (6.3) | 7 (5.5) |

| 2 | 409 (51.7) | 21 (52.5) | 167 (47.4) | 82 (64.6) |

| 3 | 196 (24.8) | 10 (25.0) | 128 (36.4) | 32 (25.2) |

| Unknown | 68 (8.6) | 3 (7.5) | 35 (9.9) | 6 (4.7) |

| BCLC, n (%) | ||||

| 0/A | 358 (45.3) | 8 (20.0) | 32 (9.1) | 5 (3.9) |

| B | 317 (40.1) | 27 (67.5) | 47 (13.3) | 19 (15.0) |

| C | 35 (4.4) | 4 (10.0) | 188 (53.4) | 86 (67.7) |

| D | 81 (10.2) | 1 (2.5) | 85 (24.1) | 17 (13.4) |

| Median max. tumor size, mm (IQR) | 38 (25–60) | 56 (39–103) | 60 (34–105) | 80 (47–109) |

| Diffuse growth pattern, n (%) | 50 (6.3) | 8 (20.0) | 123 (34.9) | 43 (33.9) |

| Intrahepatic tumor load, n (%) | ||||

| Solitary nodule | 531 (67.1) | 25 (62.5) | 123 (34.9) | 58 (45.7) |

| Multifocal nodular disease | 210 (26.5) | 7 (17.5) | 106 (30.1) | 26 (20.5) |

| Median AFP ng/ml (IQR) | 14 (5–95) | 87 (8–971) | 266 (14–4929) | 499 (29–4460) |

| Median platelet count, per nl (IQR) | 141 (90–222) | 195 (97–304) | 167 (106–251) | 182 (118–266) |

| Median cholinesterase level kU/L (IQR) | 4.8 (3.1–6.8) | 4.8 (3.2–7.3) | 4.0 (2.7–5.6) | 4.5 (3.0–6.5) |

| Median INR (IQR) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) |

| First‐line therapy, n (%) | ||||

| Resection | 234 (29.6) | 9 (22.5) | 47 (13.4) | 24 (18.9) |

| Liver transplantation | 33 (4.2) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (0.9) | 0 |

| Local ablation b | 51 (6.4) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (0.6) | 0 |

| TACE/SIRT c | 383 (48.4) | 22 (55) | 159 (45.2) | 36 (28.3) |

| Sorafenib | 25 (3.2) | 1 (2.5) | 35 (9.9) | 31 (24.4) |

| Other systemic therapy d | 3 (0.4) | 0 | 5 (1.4) | 0 |

| Best supportive care | 30 (3.8) | 2 (5.0) | 71 (20.2) | 20 (15.7) |

| Unknown | 32 (4.0) | 4 (10.0) | 30 (8.5) | 16 (12.6) |

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha‐fetoprotein; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALBI score, albumin‐bilirubin score; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; HVTT, hepatic vein tumor thrombosis; INR, international normalized ratio; IQR, interquartile range; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PSC, primary sclerotic cholangitis; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombosis; SIRT, selective internal radiation therapy; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

The sum of etiologies is >100%, because some patients had more than one etiology.

The distribution of the different types of local ablation was: n = 5 percutaneous ethanol injection, n = 35 radiofrequency ablation, n = 12 microwave ablation, n = 2 irreversible electroporation.

The distribution of the different types of intra‐arterial therapy was: n = 383 conventional transarterial chemoembolization, n = 201 drug‐eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization, n = 16 selective internal radiation therapy.

The distribution of the different types of chemotherapies was: n = 1 doxorubicin, n = 4 epirubicin, n = 2 gemcitabine + oxaliplatin, n = 1 sunitinib

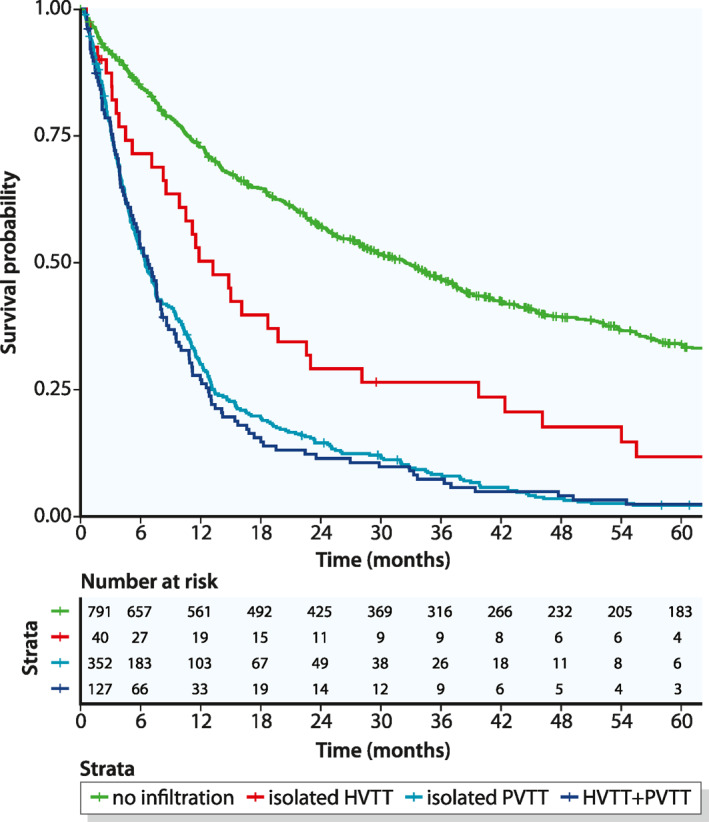

OS starting from the initial HCC diagnosis

In patients with isolated HVTT, the median OS from the initial tumor diagnosis was 13.2 months. This was significantly shorter than the median OS among patients without MVI (32.5 months, p < 0.001). However, the median OS in the HVTT group was significantly longer than that in the PVTT group (6.5 months; p = 0.002; Figure 2) or in the HVTT + PVTT group (6.7 months, p = 0.002; Figure 2). Survival rates after 1, 3, and 5 years are shown in Table 2.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan – Meier curves of overall survival, beginning at the time of the initial hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis and stratified according to the different type of macrovascular invasion. HVTT, hepatic vein tumor thrombosis; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombosis

TABLE 2.

Survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years after the initial hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis

| 1‐Year OS (95% CI) | 3‐Year OS (95% CI) | 5‐Year OS (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No infiltration | 72.8% (69.7–76.0) | 46.8% (43.3–50.5) | 33.9% (30.5–37.7) |

| Isolated HVTT | 50.3% (36.7–69.0) | 26.5% (15.6–45.0) | 11.8% (4.8–29) |

| Isolated PVTT | 30.0% (25.5–35.2) | 8.3% (5.8–11.9) | 2.2% (1.1–4.6) |

| HVTT + PVTT | 27.0% (20.2–36.1) | 7.4% (3.9–13.8) | 2.5% (0.8–7.5) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HVTT, hepatic vein tumor thrombosis; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombosis; OS, overall survival.

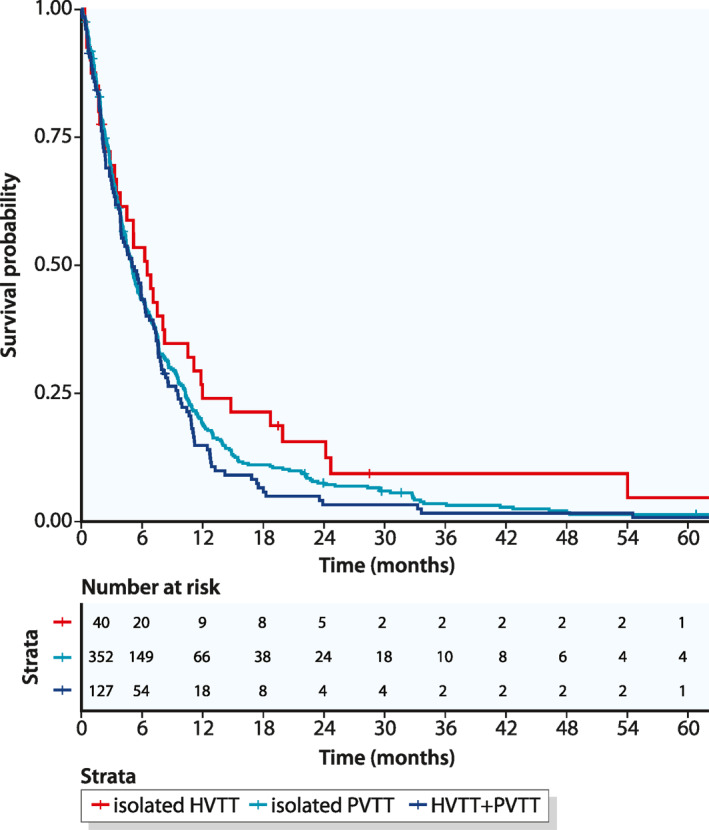

OS starting from the MVI diagnosis

Because a significant proportion of patients developed MVI during the observation period, it seemed appropriate to additionally calculate the OS starting from the first appearance of MVI. This calculation adjusted for the lead time, and thus, provided a more relevant comparison between the different types of MVI. The median OS after the MVI diagnosis was 6.5 months for patients with isolated HVTT, which was not significantly different from the median OS in patients with PVTT (5 months, p = 0.26; Figure 3) or patients with HVTT + PVTT (5 months, p = 0.17; Figure 3). Survival rates after 1, 3, and 5 years are shown in Table 3.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan – Meier curves of overall survival, beginning at the time of macrovascular invasion and stratified according to the different type of macrovascular invasion. HVTT, hepatic vein tumor thrombosis; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombosis

TABLE 3.

Survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years after the macrovascular invasion diagnosis

| 1‐Year OS (95% CI) | 3‐Year OS (95% CI) | 5‐Year OS (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated HVTT | 24.1% (13.6–42.4) | 9.4% (3.3–26.5) | 4.7% (0.8–26.5) |

| Isolated PVTT | 18.9% (15.2–23.6) | 3.5% (2.0–6.3) | 1.4% (0.5–3.7) |

| HVTT + PVTT | 14.8% (9.7–22.7) | 1.6% (0.4–6.5) | 0.8% (0.1–5.8) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HVTT, hepatic vein tumor thrombosis; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombosis; OS, overall survival.

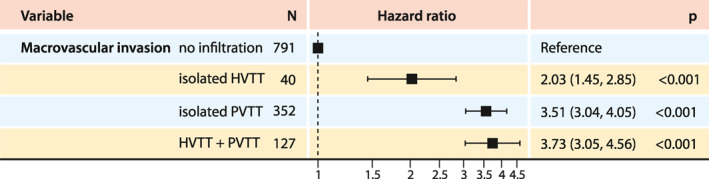

HVTT as an independent prognostic factor

Because the presence of HVTT was associated with a significantly shorter survival time compared to the absence of MVI, we assessed the prognostic value of HVTT as an independent risk factor. In a univariate Cox hazard regression analysis, all MVI subtypes were associated with significantly elevated hazard ratios (all p < 0.001; Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of Cox hazard ratios for the different types of macrovascular invasion. HVTT, hepatic vein tumor thrombosis; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombosis

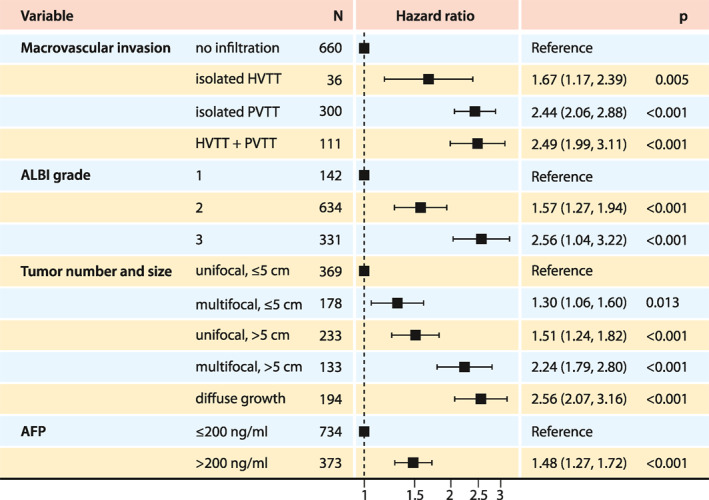

We performed a multivariate Cox regression analysis, adjusted for other established risk factors, including AFP, tumor number and size, and ALBI grade. We found that all MVI subtypes, including isolated HVTT, remained significant prognostic factors (hazard ratio for isolated HVTT, 1.7; p = 0.005; Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot of Cox hazard ratios for the different types of macrovascular invasion, after adjusting for established risk factors. AFP, alpha‐fetoprotein; ALBI grade, albumin‐bilirubin grade; HVTT, hepatic vein tumor thrombosis; PVTT, portal vein tumor thrombosis

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to address the clinical impact of HVTT in Western patients suffering from HCC. The prevalence of HVTT in our series was 12.8%, and thus considerably higher than the prevalence of 2%–5% reported by other groups. 19 , 20 , 21 The high prevalence observed in the present study might be explained by several factors. First, we are a tertiary care referral center; therefore, we might have treated a higher proportion of advanced tumor stages than centers that offer lower levels of care. Second, we retrospectively rereviewed all imaging data with a special emphasis on MVI. This approach allowed us to diagnose minor vascular invasions that could easily be missed in daily clinical routine; in contrast, other studies only relied on the routine radiological report for identifying HVTT. Third, we also included patients that developed MVI during the course of their disease; in contrast, other studies selected only patients that had vascular invasions at either the time of the initial diagnosis or the time of treatment allocation. Therefore, our results might better reflect a real‐world scenario, because we studied the complete, longitudinal course of patients. However, despite the relatively high proportion of patients with HVTT, PVTT remained far more common (12.8% HVTT vs. 36.5% PVTT). Indeed, most patients with HVTT presented with concomitant PVTT (3.1% isolated HVTT vs. 9.7% HVTT + PVTT).

Interestingly, the proportion of patients that developed MVI after the initial HCC diagnosis was significantly higher in the HVTT group (54.5%) compared to the PVTT group (37.2%, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the median interval between the initial HCC diagnosis and the first MVI diagnosis was considerably longer for isolated HVTT than for isolated PVTT (387 vs. 95 days, p = 0.006). This finding, to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported previously.

Both the higher proportion of PVTT over HVTT and the shorter interval to developing PVTT compared to HVTT supports the concept that the portal venous system is preferentially invaded in HCC. This finding is in line with the consistently reported predominance of portal vein versus hepatic vein invasion 22 and the high coincidence of PVTT in patients with HVTT. 9 , 19 Some theories have been proposed to explain this privileged invasion of the portal venous system by HCC. One theory holds that there might be specific growth factors in the portal venous blood. 23 Another theory hypothesizes a change of the vascular pattern in the tumor environment with the establishment of retrograde portal venous flow. 24 An extensive discussion of this subject was recently published by Subbotin. 25 Nevertheless, the exact mechanism of vascular invasion remains mainly unknown.

The results of the present study indicate that patients with HVTT have significantly worse survival compared to patients without MVI. Moreover, HVTT remained a significant independent risk factor for poor survival after the multivariate analysis was adjusted for other established risk factors. At first glance, patients with isolated HVTT appeared to have a better prognosis than patients with PVTT, when survival was calculated from the initial tumor diagnosis (median OS, 13.2 vs. 6.5 months). However, the interval between the HCC diagnosis and the MVI occurrence was longer for HVTT than for PVTT; thus, the survival benefit for patients with isolated HVTT was lost when survival was calculated from the first appearance of the MVI (median OS, 6.5 vs. 5 months; p = 0.2). The latter approach for calculating OS is probably more appropriate than a calculation from the HCC diagnosis, because vascular invasion cannot be predicted, and in clinical routine, treatment decisions can only be made after the vascular invasion is diagnosed.

Previous reports showed significantly different survival between patients with isolated HVTT and patients with PVTT, but the findings were conflicting. For example, Zhang et al. 26 compared outcomes among patients with HVTT that underwent either a resection or TACE. They found that, after surgical resection, survival was better in patients with PVTT than in patients with HVTT. In addition, their multivariate analysis showed that concomitant PVTT was a significant risk factor for poor survival in both treatment regimes. In contrast, Kokudo et al. 21 reported that survival was significantly better in the HVTT group than in the PVTT group following liver resection.

Much controversy remains regarding the optimal treatment for patients with MVI. Western guidelines propose systemic therapy. 10 , 11 However, Eastern guidelines are more liberal, because they also consider other treatment modalities, like resection, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy, and TACE. 27 , 28 Unfortunately, our data cannot provide further guidance on this topic, because the number of patients with isolated HVTT was too small to draw relevant conclusions on treatment strategy. However, given the same deleterious impact on survival of patients with HVTT compared to patients with PVTT in our study, we propose to also classify patients with HVTT as advanced stage (BCLC C).

The main limitation of this study was the retrospective design. Because of the retrospective analysis of the imaging data and the dedicated focus on vascular invasion, we might have identified vascular invasion earlier and more frequently than in clinical routine. Furthermore, due to the scarcity of HVTT, the isolated HVTT group was relatively small; therefore, it would be desirable to confirm the results in a multicenter analysis. Nevertheless, this study represents the largest cohort of Western patients with HVTT described to date.

In conclusion, HVTT might be more common than previously reported, but it appears to develop at a later stage than PVTT. Nevertheless, once the tumor starts to invade the hepatic vein, the prognosis is similarly poor for patients with HVTT and those with PVTT. Furthermore, HVTT was identified as an independent risk factor. Thus, it is reasonable to classify patients with HVTT as advanced stage (BCLC C).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Peter R. Galle has received grants and personal fees from Bayer and personal fees from Bristol‐Myers Squibb, MSD Sharp & Dohme, Lilly, Sillajen, SIRTEX, and AstraZeneca. Arndt Weinmann has received speaker fees and travel grants from Bayer. Daniel P. Dos Santos has received personal fees from Cook. Roman Kloeckner has received speaker fees from BTG, Guerbet, and SIRTEX and personal fees from Boston Scientific, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Guerbet, and SIRTEX. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICS APPROVAL

The study was approved by the responsible ethics body (Ethics committee of the Medical Association of Rhineland‐Palatinate, Germany) for the retrospective analysis of clinical data. Additional examinations were not performed. Patient records and information were anonymized and deidentified prior to analysis.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study includes parts of the doctoral thesis of one of the authors (F. I. M.). The authors thank Verena Steinle for her valuable assistance in image analysis. They further thank Sandra Koch for her valuable assistance with data management.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nakashima T, Okuda K, Kojiro M, Jimi A, Yamaguchi R, Sakamoto K, et al. Pathology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: 232 consecutive cases autopsied in ten years. Cancer. 1983;51:863–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kudo M, Izumi N, Ichida T, Ku Y, Kokudo N, Sakamoto M, et al. Report of the 19th follow‐up survey of primary liver cancer in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:372–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cabibbo G, Enea M, Attanasio M, Bruix J, Craxì A, Cammà C. A meta‐analysis of survival rates of untreated patients in randomized clinical trials of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2010;51:1274–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tandon P, Garcia‐Tsao G. Prognostic indicators in hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of 72 studies. Liver Int. 2009;29:502–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mähringer‐Kunz A, Steinle V, Düber C, Weinmann A, Koch S, Schmidtmann I, et al. Extent of portal vein tumour thrombosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: the more, the worse? Liver Int. 2019;39:324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chung SM, Yoon CJ, Lee SS, Hong S, Chung JW, Yang SW, et al. Treatment outcomes of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma that invades hepatic vein or inferior vena cava. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37:1507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Y, Ma L, Yuan Z, Zheng J, Li W. Percutaneous thermal ablation combined with TACE versus TACE monotherapy in the treatment for liver cancer with hepatic vein tumor thrombus: a retrospective study. PloS One. 2018;13:e0201525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kokudo T, Hasegawa K, Yamamoto S, Shindoh J, Takemura N, Aoki T, et al. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatic vein tumor thrombosis. J Hepatol. 2014;61:583–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Galle PR, Forner A, Llovet JM, Mazzaferro V, Piscaglia F, Raoul J‐L, et al. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:358–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weinmann A, Koch S, Niederle IM, Schulze‐Bergkamen H, König J, Hoppe‐Lotichius M, et al. Trends in epidemiology, treatment, and survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients between 1998 and 2009. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:279–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Canellas R, Mehrkhani F, Patino M, Kambadakone A, Sahani D. Characterization of portal vein thrombosis (neoplastic versus bland) on CT images using software‐based texture analysis and thrombus density (hounsfield units). Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207:W81–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thompson SM, Wells ML, Andrews JC, Ehman EC, Menias CO, Hallemeier CL, et al. Venous invasion by hepatic tumors: imaging appearance and implications for management. Abdom Radiol. 2018;43:1947–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Catalano OA, Choy G, Zhu A, Hahn PF, Sahani DV. Differentiation of malignant thrombus from bland thrombus of the portal vein in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: application of diffusion‐weighted MR imaging. Radiology. 2010;254:154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li C, Hu J, Zhou D, Zhao J, Ma K, Yin X, et al. Differentiation of bland from neoplastic thrombus of the portal vein in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: application of susceptibility‐weighted MR imaging. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:590. 10.1186/1471-2407-14-590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan . The general rules for the clinical and pathological study of primary liver cancer. Jpn J Surg. 1989;19:98–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen Z‐H, Wang K, Zhang X‐P, Feng J‐K, Chai Z‐T, Guo W‐X, et al. A new classification for hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatic vein tumor thrombus. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2020;9:717–28. 10.21037/hbsn.2019.10.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim H‐C, Lee J‐H, Chung JW, Kang B, Yoon J‐H, Kim YJ, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization with additional cisplatin infusion for hepatocellular carcinoma invading the hepatic vein. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;24:274–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takayasu K, Arii S, Ikai I, Omata M, Okita K, Ichida T, et al. Prospective cohort study of transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in 8510 patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:461–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kokudo T, Hasegawa K, Matsuyama Y, Takayama T, Izumi N, Kadoya M, et al. Liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatic vein invasion: a Japanese nationwide survey. Hepatology. 2017;66:510–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ikai I, Kudo M, Arii S, Omata M, Kojiro M, Sakamoto M, et al. Report of the 18th follow‐up survey of primary liver cancer in Japan. Hepatol Res 2010;40:1043–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tang Y, Yu H, Zhang L, Wang K, Guo W, Shi J, et al. Experimental study on enhancement of the metastatic potential of portal vein tumor thrombus‐originated hepatocellular carcinoma cells using portal vein serum. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:588–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mitsunobu M, Toyosaka A, Oriyama T, Okamoto E, Nakao N. Intrahepatic metastases in hepatocellular carcinoma: the role of the portal vein as an efferent vessel. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1996;14:520–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Subbotin VM. A hypothesis on paradoxical privileged portal vein metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Can organ evolution shed light on patterns of human pathology, and vice versa? Med Hypotheses. 2019;126:109–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang Y‐F, Wei W, Guo Z‐X, Wang J‐H, Shi M, Guo R‐P. Hepatic resection versus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with hepatic vein tumor thrombus. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015;45:837–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kudo M, Matsui O, Izumi N, Iijima H, Kadoya M, Imai Y, et al. JSH consensus‐based clinical practice guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2014 update by the liver cancer study group of Japan. Liver Cancer. 2014;3:458–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yau T, Tang VYF, Yao T‐J, Fan S‐T, Lo C‐M, Poon RTP. Development of Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system with treatment stratification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1691–700.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.