The signal transduction pathways associated with interactions with small organic molecules attract great interest in the field of chemical biology. To study the action of bioactive compounds in detail, it is necessary to eliminate the signaling complexity caused by multiple combined effects. The development of “caged” compounds, which are not active when the pharmacophore is blocked by a photoactivatable moiety, has been a powerful tool with which to approach this problem. Triggered by photoirradiation to a limited area in the cell, the specific effects of the ligand in that location can then be observed over time. Several strategies for “caging” molecules have been developed and each approach has its own advantages.[1]

The protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms play pivotal roles in physiological responses to growth factors and oxidative stress mediated through the endogenous second messenger 1,2-diacylglycerol (DAG). These responses regulate numerous cellular processes,[2] including proliferation,[3] differentiation,[4] migration,[5] and apoptosis.[6] The tumor-promoting phorbol esters, potent analogues of DAG, have provided a convenient probe of PKC function. Ligand binding to the C1b domain in PKC leads to its membrane translocation. The translocation of PKC is of central importance for its function because the localization of PKC determines the substrates to which it has access.[7] Despite the complex regulatory mechanisms of PKC activation, considerable progress in understanding isozyme-specific functions has been made.[8] Development of ligands with high specificities for PKC isozymes has been a critical issue in the medicinal field.[9a–b] Enhancement of the understanding of targets and signaling pathways would provide important insights contributing to this effort.

As high-affinity ligands for PKC, DAG-lactones have established the importance of the pharmacophore triad of two carbonyl groups (sn-1 and sn-2) and the hydroxy group being maintained intact.[8] In this study, we have utilized coumarin-based “caging” molecules including 6-bromo-7-hydroxycoumarin (Bhc)[10] and 6-bromo-7-methoxycoumarin (Bmc)[11] to block the binding of DAG-lactones to PKCδ. The caged protecting groups are attached to the primary alcohol, which is an important DAG-lactone pharmacophore. Photolytic uncaging of the blocked DAG-lactone then provides a means of driving PKC activation within the cell at desired specific locations and times. An approach previously used to achieve this goal has been the use of caged diacylglycerols.[1d, 12] DAG-lactones have several potential advantages. Extensive medical chemistry investigations have yielded DAG-lactones with substantially enhanced affinities, a range of physiochemical properties, and interesting biological selectivities with regard to diacylglycerol targets.[8]

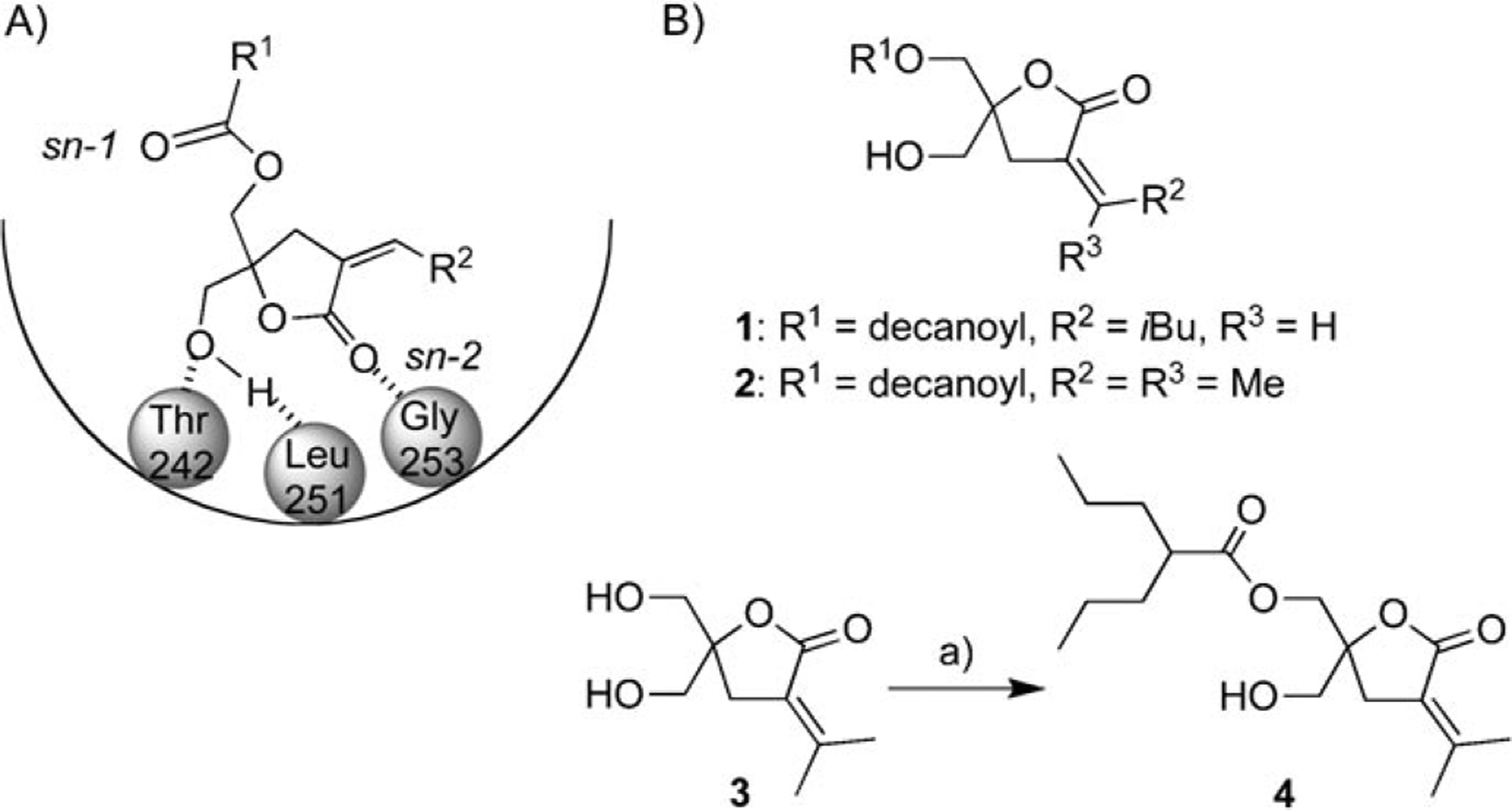

The DAG-lactones have been developed as ligands for PKC isozymes with low-nanomolar binding affinities by a combination of pharmacophore- and receptor-guided approaches based on the structure of the physiological second messenger DAG (Scheme 1).[8] The DAG-lactones were designed by the pharmacophore-guided approach based on the geometries of bioequivalent pharmacophores present in DAG and in phorbol esters.[13] In the DAG-lactone structure, the glycerol backbone was constrained to a γ-lactone ring to reduce the entropic penalty associated with DAG binding. In binding to PKC, the linear or branched acyl (R1) or α-alkylidene (R2) chains contribute to optimized hydrophobic interactions with a group of conserved hydrophobic amino acids located on the top half of the C1 domain. There are two competing binding modes (sn-1 and sn-2), depending on which carbonyl group is directly involved in binding to the protein (Scheme 1A). In general, it has been found that DAG favors sn-1 binding, whereas the corresponding DAG-lactone analogues favor sn-2 binding.[8] In this study, three representative DAG-lactones—1, 2, and 4 (Scheme 1B)—were investigated. Compound 1 had previously been reported as part of a branched α-alkylidene series that provided the most potent α-alkylidene analogues.[9, 14] Comparison of the binding affinities of the stereoisomers showed that the Z isomer of lactone 1 had a higher affinity for PKCδ than the E isomer. The Z isomer of compound 1 was therefore purified by flash chromatography and utilized for experiments. Compound 2 had also previously been synthesized to assess the role of a flexible decanoic acid chain at the acyl chain position (R1).[9a] Compound 4 was synthesized as a compound with a branched chain as an acyloxy moiety and an isopropyl system as an α-alkylidene group; a similar compound with a more branched acyloxy moiety has been reported.[15] The lactones 2 and 4 each contain an isopropylidene group at the α-alkylidene position, which has been identified as one of the principal determinants for control of biological activity. The effect of the acyl group on the isozyme specificity of the DAG-lactones has been investigated with a series of compounds.

Scheme 1.

A) The sn-2 binding model of DAG-lactones to the PKCδ C1b domain and membrane. B) Structures of the DAG-lactones 1, 2, and 4. a) 2-Pro-pylpentanoyl chloride, pyridine, CH2Cl2, 24%.

The binding affinities of the DAG-lactones were determined as described previously.[16] The Ki values of the compounds were determined as 8.4 ± 2.9, 6.5 ± 0.8, and 22 ± 1.6 nm (mean ± SEM) for 1, 2, and 4, respectively. The binding affinities of 1 and 2 were compatible with those in the previous reports[9a, 15b] (2.3 and 15.9 nm, respectively), whereas that of 4 was weaker than those of the related compounds. It has been reported that branched chains interfere with the interaction with the hydrophobic surface of the C1b domain in the sn-2 binding mode of DAG-lactones. As reported previously, the acyl and α-alkylidene moieties affect PKCδ translocation caused by ligand binding. To reveal the translocation caused by the synthesized DAG-lactones, CHO-K1 cells expressing a PKCδ-EGFP fusion construct were prepared and the PKCδ-EGFP was visualized by confocal microscopy as a function of time after ligand addition (Figure 1A–C). Compound 1 at 10 μm did not cause translocation of PKCδ even 30 min after addition (data not shown). Compound 2 caused rapid translocation, requiring 5 min for complete translocation. Compound 4 caused less complete and slower translocation, perhaps reflecting its weaker potency. As described for other DAG-lactones, translocation was predominantly to internal membrane compartments (nuclear membrane, mitochondria, and other cellular organelles).[17] From these studies, compound 2 was selected as the most suitable for photoactivation analysis with the aid of caged protecting groups.

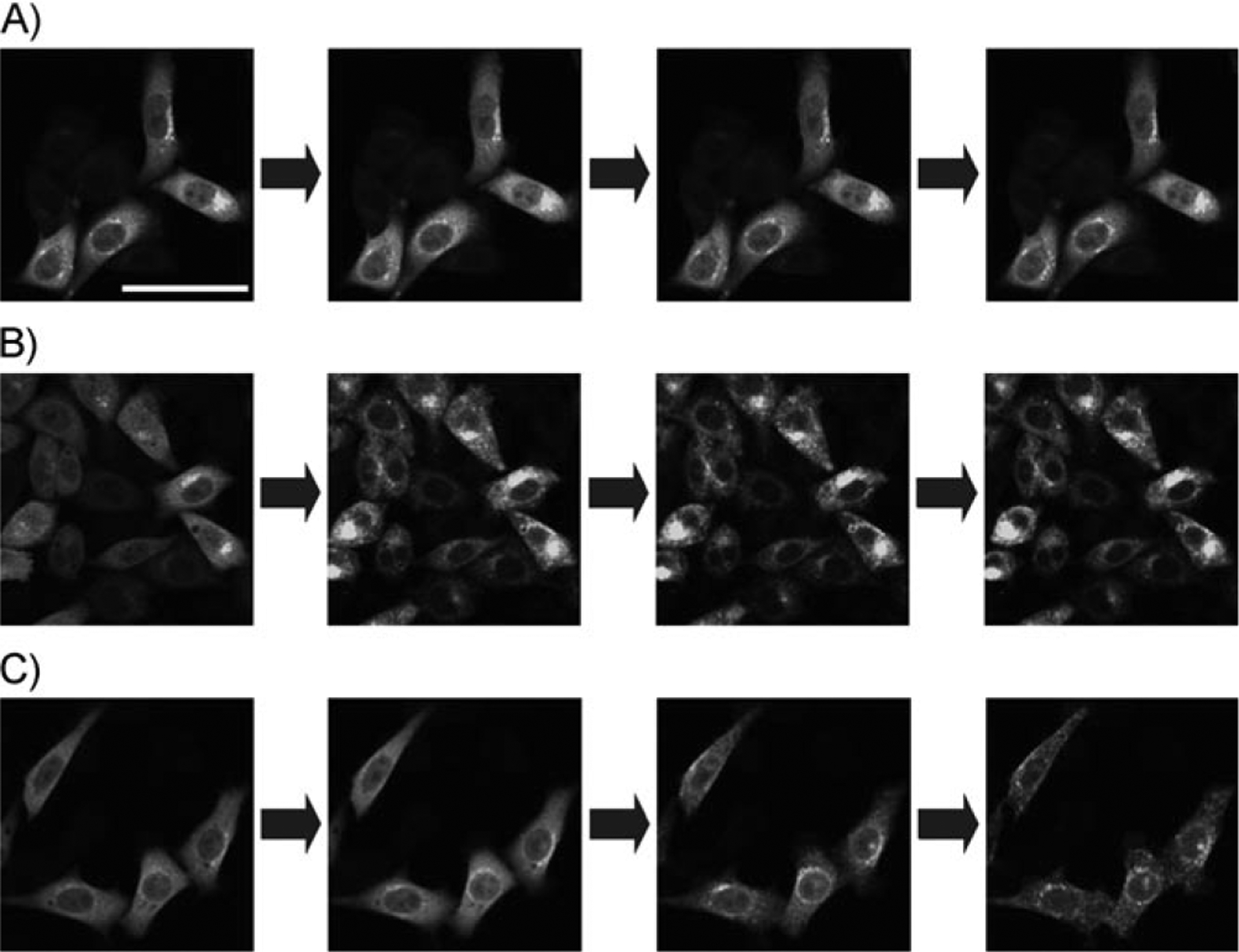

Figure 1.

Translocation of PKCδ caused by compounds 1, 2, and 4. A)–C) Time-dependent translocation of compounds 1, 2, and 4, respectively (0, 1, 5, and 10 min after addition of compounds). The final concentration of the compounds was 10 μm. The scale bar indicates 50 μm.

To study PKCδ activation by photolysis of ligands, caged compounds were synthesized as depicted in Scheme 1B. As caging moieties, (6-bromo-7-hydroxycoumarin-4-yl)methoxycarbonyl (Bhcmoc) and (6-bromo-7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl)methoxycarbonyl (Bmcmoc) were utilized. Several caged compounds based on these caging moieties have been reported previously.[1c] As one of the most commonly used classes of structures for the protection of phosphate, amine, and carbonyl functional groups, coumarin-based protecting groups including MCM,[18] HCM (and ACM),[19] DMCM,[20] BCMCM,[21] DMACM (and DEACM),[22] and Bhc[10] have been successfully developed.Given its critical role in forming two of the three hydrogen bonds driving binding of the DAG-lactone to the binding pocket of the C1 domain, the hydroxy group of the DAG-lactone was the obvious site for addition of the coumarin-based protecting group in order to disrupt binding (Scheme 1A).

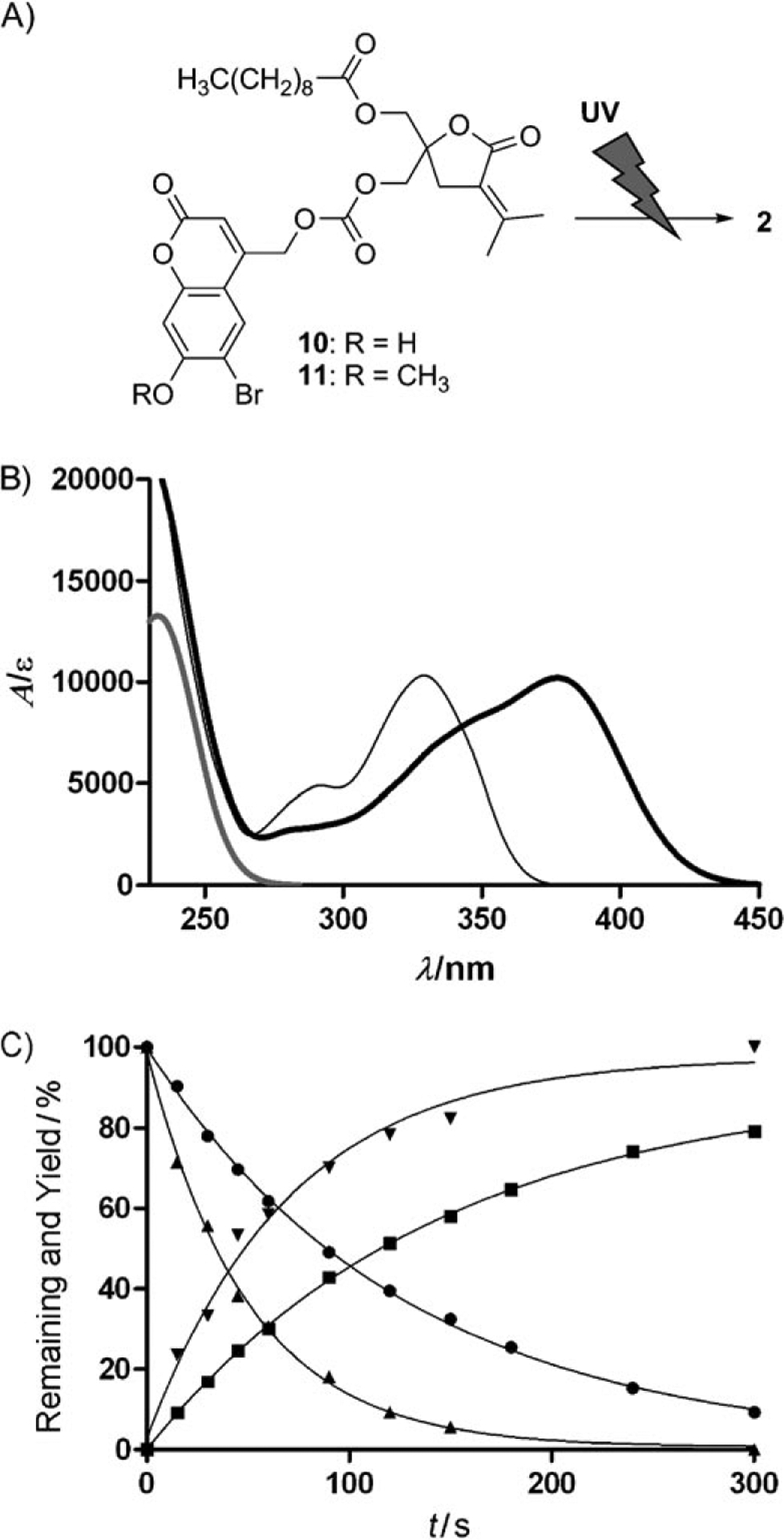

The function of the Bhc- and Bmc-protected DAG-lactones 10 and 11 as “phototriggers” (Figure 2A) was evaluated in terms of several parameters. Firstly, the UV spectra of the compounds were determined (Figure 2B). The compounds showed clear absorbance originating from the caged moiety. The absorbance maxima for Bhc-2 and Bmc-2 were 377 and 329 nm, respectively. Next, photolysis was performed with the aid of a photochemical lamp (RPR3500 Å). The breakdown of the caged compounds and the production of the uncaged compounds were monitored by HPLC and the extent of the reaction was calculated from the peak areas, which were determined as a function of irradiation time (Figure 2C). Quantitative production of the parent compound 2 was successfully observed. The preferred environment of the caging groups for photolysis is thus hydrophilic, accounting for the superiority of the Bhc group over the Bmc group in photolysis efficiency (Table S1 in the Supporting Information). The photochemical properties of Bmc-1 and Bmc-4 were also assessed. The results support the view that compound 2 is suitable for photoactivation analysis (Figures S1, S2, and Table S2).

Figure 2.

Structures of the caged compounds Bhc-2 (10) and Bmc-2 (11) and their photochemical properties. A) Representation of photochemical cleavage of the caged compounds 2. B) UV spectra of 2 (gray line), Bhc-2 (thick black line), and Bmc-2 (thin black line). C) Plots of one-photon photolysis experiments. The plots show Bhc-2 remaining (▲), Bhc-2 product (▼), Bmc-2 remaining (●), and Bmc-2 product (■).)

To evaluate the binding affinities of the caged compounds, competitive binding analysis to PKCδ was performed as described previously.[16] The results indicated that the caged compounds, in which the hydroxy group was protected, showed decreases in binding affinity of more than 100-fold (Table S1). The measured binding affinities of Bhc-2 (10) and Bmc-2 (11) to PKCδ were 431 and 940 nm, respectively. For comparison, compound 2 without the blocking group had an affinity of 6.5 nm. In the proposed binding mode of the DAG-lactones to PKC, the carbonyl oxygen of the DAG-lactone interacts with Gly253 of PKCδ, and the hydrogen and oxygen of the hydroxy group interact with Leu251 and Thr242, respectively. In the sn-2 binding mode, which is known to be preferred by DAG-lactones, the acyl group is proposed to interact with the lipid bilayer of the cellular membranes. In this mode, the caged hydroxy group cannot interact with Leu 251 or Thr242. The caged DAG-lactones thus successfully displayed “loss of function” in binding, a requisite property of caged compounds. To examine the effects on translocation of PKCδ in mammalian cells, the caged compounds Bhc-2 and Bmc-2 were added to medium at 10 μm, a concentration at which compound 2 caused rapid translocation. Consistently with their loss of binding affinity for PKCδ, as shown by the in vitro analysis, the caged compounds failed to induce PKCδ translocation, confirming that the activation of PKCδ by compound 2 is successfully retarded by caging (Figure S3). The behavior of Bhc-2 (10) upon photolysis was also evaluated under the confocal microscope. Of the synthetic compounds in this study, Bhc-2 was most suitable for the purpose in terms of the efficiency of the photolysis reaction and rapid translocation of PKCδ. Translocation and reactivation of kinase activity by uncaged Bhc-2 were confirmed (Figure S4).

To elucidate PKC-related signal transduction by stimulation of ligand binding, spatially and temporally controlled activation is desirable. To assess this point, photoirradiation at a limited region of interest (ROI) in the cell was performed. Because photolysis will only unblock caged ligand located in the irradiated region, the response following the activation should reflect this time- and location-dependent generation of active ligand. As shown in Figure 3, translocation was observed at 10 min after photoirradiation of Bhc-2 (10). The pattern of sub-cellular localization was similar to that of compound 2 as shown in Figure 1. However, the time-course of translocation was dramatically slower, taking 10 min, in contrast with the rapid response seen upon addition of compound 2. We conclude that the photolysis of compound Bhc-2 was successful, in that translocation was observed. The slow kinetics are consistent with the concentration of the released DAG-lactone 2 being relatively low, which would be expected because the photolysis reaction occurred in the limited area of the ROI. Additionally, the cells around the ROI target cell also showed translocation of PKCδ. This effect might be caused by the release of uncaged compound and its reuptake by surrounding cells. The DAG-lactones are highly lipophilic, with their computed logP values ranging from 3 to 5. This property allows DAG-lactones to complete the hydrophobic surface of the C1b domain of PKCδ and to interact with the lipid bilayer of the membrane. However, the lipophilicity of the DAG-lactones also allows the compounds to permeate through membranes and to be released back into the medium, making them available for reuptake.

Figure 3.

Translocation activated by photolysis of Bhc-2 (10). The region of interest (ROI) is limited to the inside of the circle [orange in (A)]. The panels show the translocation of EGFP-PKCδ fusion protein in a time-course as follows: A) before photoirradiation, B) 2 min, C) 5 min, and D) 10 min after photoirradiation. The image in each panel shows EGFP fluorescence. The scale bar indicates 20 μm. The detailed pictures with pseudocolors are given in Figure S5. E) Fluorescent intensity mapped along the orange bar from (i) to (ii) in the panel. The thin and thick lines show the intensity at 0 and 10 min of photoirradiation, respectively.

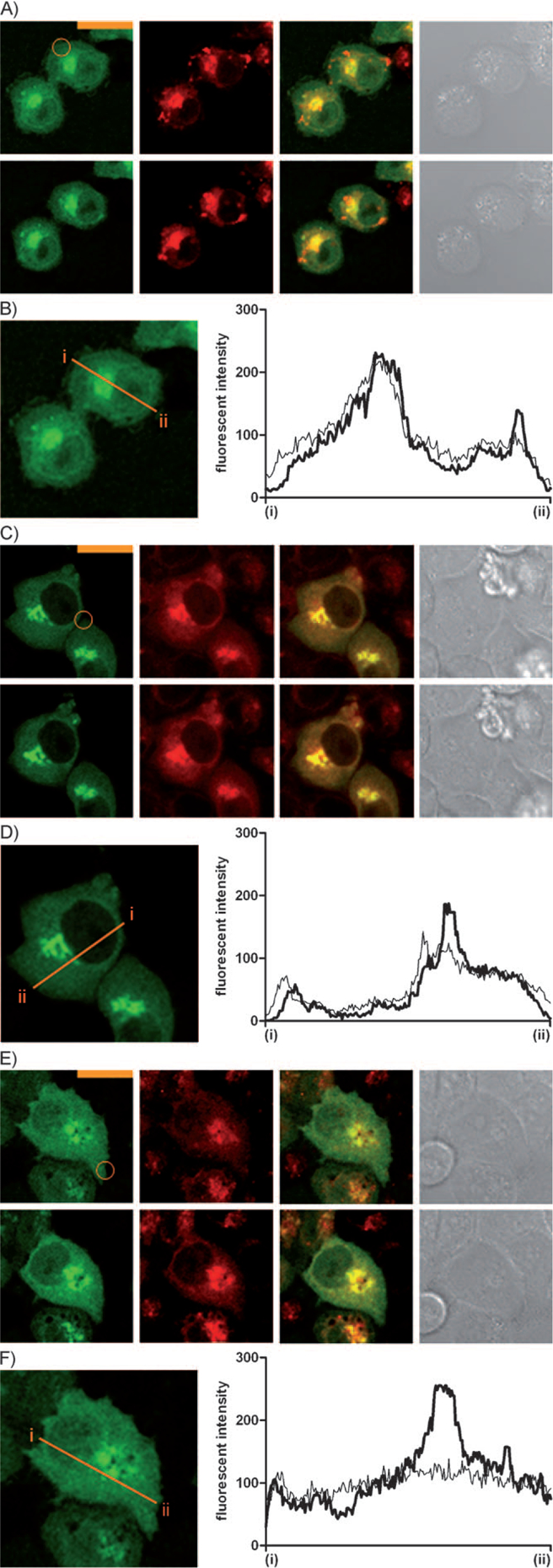

It has been shown that patterns and kinetics of translocation of activated PKCδ depend on the lipophilicity and side-chain structures of DAG-lactones.[8] For compound 2, it was possible that the translocation caused is to the Golgi apparatus, because the activated PKCδ is accumulated to the perinuclear region. To confirm the translocation to the Golgi apparatus, cellular staining by BODIPY TR ceramide was performed on CHO-K1 cells expressing PKCδ-EGFP. Compound 2 was added to these cells at 10 μm. After 10 min of compound addition, the amount of PKCδ that had colocalized with Golgi apparatus was increased (Figure S6). In the next study to determine the differences in translocation between cell lines, A549 and HeLa were utilized in addition to CHO-K1 cells. As shown in Figure 4, photoirradiation induced translocation of PKCδ in all cell lines. In comparison with the stimulation by compound 2, translocation was modest because of the low concentration of released compound 2 as discussed above. Of the cell types examined, HeLa cells showed most distinctive translocation to Golgi apparatus and nuclear membrane.

Figure 4.

Observation of translocation of activated PKCδ within the Golgi-stained cells by photolysis of Bhc-2 (10) in ROI. The cells are: A) CHO-K1, C) A549, and E) HeLa. The ROI is limited to the inside of the orange circles. Each set of cell images shows before photoirradiation (top) and 10 min after (bottom); EGFP-PKCδ, staining by BODIPY TR ceramide, merged image, and differential interference contrast (DIC) from left to right. The scale bars indicate 20 μm. B), D), and F) Fluorescent intensities mapped along the orange bars from (i) to (ii) in the panels. The thin and thick lines show the intensity at 0 and 10 min of photoirradiation, respectively.

In this study, the Bhc- and Bmc-caged DAG-lactones were prepared and evaluated in terms of photochemical control of PKC activation. DAG-lactone binding to PKCδ in mammalian cells was successfully controlled through photoirradiation. Derivatization at the DAG-lactone hydroxy group was shown to be very effective for diminishing affinity towards PKC. Photoactivation limited to the ROI was successfully regulated. However, there remained effects on other cells near the cells of interest, and this needs to be addressed in future studies. Development of more precise photochemical control methodology will be needed to address the signaling mechanism related to PKCδ in a single cell or at a single location within a single cell. None-theless, these results indicate the potential of this approach for studying PKC function.[1b, c]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Kazunari Akiyoshi (Institute of Biomaterials and Bioengineering, Tokyo Medical and Dental University) for assistance with the laser microscopy. This study was supported in part by the Naito Foundation for Science (to W.N.) and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute. N.O. is supported by the Japan Society for Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cbic.201000670.

References

- [1].a) Dormán G, Prestwich GD, Trends Biotechnol 2000, 18, 64–77; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mayer G, Heckel A, Angew. Chem 2006, 118, 5020–5042; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 4900–4921; [Google Scholar]; c) Lee H-M, Larson DR, Lawrence DS, ACS Chem. Biol 2009, 4, 409–427; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Quann EJ, Merino E, Furuta T, Huse M, Nat. Immunol 2009, 10, 627–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Nishizuka Y, Science 1992, 258, 607–614; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Newton AC, J. Biol. Chem 1995, 270, 28495–28498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Watanabe T, Ono Y, Taniyama Y, Hazama K, Igarashi K, Ogita K, Kikkawa U, Nishizuka Y, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 10159–10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mischak H, Pierce JH, Goodnight J, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Mushinski JF, J. Biol. Chem 1993, 268, 20110–20115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li C, Wernig E, Leitges M, Hu Y, Xu Q, FASEB J 2003, 17, 2106–2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Ghayur T, Hugunin M, Talanian RV, Ratnofsky S, Quinlan C, Emoto Y, Pandey P, Datta R, Huang Y, Kharbanda S, Allen H, Kamen R, Wong W, Kufe D, J. Exp. Med 1996, 184, 2399–2404; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Alkon DL, Sun M-K, Nelson TJ, Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2007, 28, 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang QJ, Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2006, 27, 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Marquez VE, Blumberg PM, Acc. Chem. Res 2003, 36, 434–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Nacro K, Bienfait B, Lee J, Han K-C, Kang J-H, Benzaria S, Lewin NE, Bhattacharyya DK, Blumberg PM, Marquez VE, J. Med. Chem 2000, 43, 921–944; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tamamura H, Beinfait B, Nacro K, Lewin NE, Blumberg PM, Marquez VE, J. Med. Chem 2000, 43, 3210–3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Furuta T, Wang SS-H, Dantzker JL, Dore TM, Bybee WJ, Callaway EM, Denk W, Tsien RY, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 1193 – 1200; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ando H, Furuta T, Tsien RY, Okamoto H, Nat. Genet 2001, 28, 317–325; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Montgomery HJ, Perdicakis B, Fishlock D, Lajoie GA, Jervis E, Guillemette JG, Bioorg. Med. Chem 2002, 10, 1919–1927; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lin W, Lawrence DS, J. Org. Chem 2002, 67, 2723–2726; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Lu M, Fedoryak OD, Moister BR, Dore TM, Org. Lett 2003, 5, 2119–2122; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Suzuki AZ, Watanabe T, Kawamoto M, Nishiyama K, Yamashita H, Ishii M, Iwamura M, Furuta T, Org. Lett 2003, 5, 4867–4870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Furuta T, Watanabe T, Tanabe S, Sakyo J, Matsuba C, Org. Lett 2007, 9, 4717–4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Huang XP, Sreekumar R, Patel JR, Walker JW, Biophys. J 1996, 70, 2448–2457; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Robu VG, Pfeiffer ES, Robia SL, Balijepalli RC, Pi Y, Kamp TJ, Walker JW, J. Biol. Chem 2003, 278, 48154–48161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Kishi Y, Rando RR, Acc. Chem. Res 1998, 31, 163–172; [Google Scholar]; b) Wender PA, Cribbs CM, Koehler KF, Sharkey NA, Herald CL, Kamano Y, Petit GR, Blumberg PM, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 7197–7201; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang S, Milne GWA, Nicklaus MC, Marquez VE, Lee J, Blumberg PM, J. Med. Chem 1994, 37, 1326–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Tamamura H, Sugano DM, Lewin NE, Blumberg PM, Marquez VE, J. Med. Chem 2004, 47, 644–655; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Malolanarasimhan K, Kedei N, Sigano DM, Kelley JA, Lai CC, Lewin NE, Surawski RJ, Pavlyukovets VA, Garfield SH, Wincovitch S, Blumberg PM, Marquez VE, J. Med. Chem 2007, 50, 962–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sigano DM, Peach ML, Nacro K, Choi Y, Lewin NE, Nicklaus MC, Blumberg PM, Marquez VE, J. Med. Chem 2003, 46, 1571–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Sharkey NA, Blumberg PM, Cancer Res 1985, 45, 19–24; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kazanietz MG, Krausz KW, Blumberg PM, J. Biol. Chem 1992, 267, 20878 – 20886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Li L, Lorenzo PS, Bogi K, Blumberg PM, Yupsa SH, Mol. Cell. Biol 1999, 19, 8547–8558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Furuta T, Torigai H, Sugimoto M, Iwamura M, J. Org. Chem 1995, 60, 3953–3956; [Google Scholar]; b) Schade B, Hagen V, Schmidt R, Herbrich R, Krause E, Eckardt T, Bendig J, J. Org. Chem 1999, 64, 9109–9117. [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Furuta T, Momotake A, Sugimoto M, Hatayama M, Iwamura M, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1996, 228, 193–198; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Furuta T, Iwamura M, Methods Enzymol 1998, 291, 50–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Eckardt T, Hagen V, Schade B, Schmidt R, Schweitzer C, Bendig J, J. Org. Chem 2002, 67, 703–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].a) Hagen V, Bendig J, Frings S, Eckardt T, Helm S, Reuter D, Kaupp UB, Angew. Chem 2001, 113, 1077–1080; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 1045–1048; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hagen V, Frings S, Bendig J, Lorenz D, Wiesner B, Kaupp UB, Angew. Chem 2002, 114, 3775–3777; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 3625–3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Geißler D, Kresse W, Wiesner B, Bendig J, Kettenmann H, Hagen V, ChemBioChem 2003, 4, 162–170; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hagen V, Frings S, Wiesner B, Helm S, Kaupp UB, Bendig J, ChemBioChem 2003, 4, 434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.