Abstract

Background:

Uterine carcinosarcomas (UCSs) are aggressive neoplasms composed of high-grade malignant epithelial and mesenchymal elements with most (~90%) showing TP53 abnormalities. A subset, however, shows mismatch repair deficiency (MMR-D). We sought to describe their clinical, morphologic and molecular features.

Methods:

Clinicopathologic data of MMR-D UCSs were recorded including age, stage, follow-up, MMR and p53 immunohistochemistry (IHC), MLH1 promoter methylation status, and germline alterations, TP53 mutation status, microsatellite instability and mutational burden by massively parallel sequencing.

Results:

Seventeen (6.2%) MMR-D were identified among 276 UCSs. Of MMR-D UCSs, the median age was 60 years. MMR IHC loss is as follows: MLH1/PMS2 65%, MSH2/MSH6 18%, MSH6 12%, and PMS2 6%. MLH1 promoter methylation and Lynch syndrome was identified in 47% and 12% of cases respectively. Cases with p53 IHC showed the following patterns: wild-type 70%, aberrant 20%, and equivocal 10%. Of cases with sequencing, 88% were hypermutated and microsatellite high. High-grade endometrioid, undifferentiated, and clear cell carcinoma was present in 53%, 41%, and 6% of cases respectively and 47% also showed a low-grade endometrioid component. Most patients presented at early stage (67%) and upon follow-up, 18% died of disease, 65% showed no evidence of disease (NED) while 18% are alive with disease.

Conclusion:

Patients with MMR-D UCS are younger than the reported median age (70 years) for traditional UCS and most do not show p53 abnormalities. Low-grade endometrioid and undifferentiated carcinoma were seen in approximately half of all cases. Although UCSs have a high tendency for early extrauterine spread, most patients in our cohort presented at early stage and at follow up were NED. MMR-D UCSs display distinct clinical, morphologic, and molecular features compared to traditional UCSs.

Keywords: Uterine carcinosarcomas, DNA mismatch repair deficiency, Microsatellite instability, Hypermutated phenotype

1. INTRODUCTION

Carcinosarcomas, also known as “malignant mixed Mullerian tumor” or MMMT, are biphasic neoplasms that are composed of malignant epithelial and sarcomatous elements [1–4]. Carcinosarcomas are uncommon tumors that can occur in any organ of the gynecologic tract, and commonly arise in the uterus, accounting for less than 5% of all uterine malignancies [4–6].

Histologically, uterine carcinosarcomas (UCSs) are composed of a high-grade carcinoma [3, 7] admixed with high-grade malignant mesenchymal elements. Both components are distinct and typically sharply demarcated. The epithelial component is commonly represented by serous carcinoma, high-grade endometrioid or high-grade adenocarcinoma with ambiguous features, but clear cell, mucinous, squamous and undifferentiated carcinomas have been also described [4, 8]. Based on the mesenchymal components, carcinosarcomas are divided into homologous and heterologous types, with the latter demonstrating extrinsic differentiation not encountered in non-neoplastic uteri (chondrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, liposarcoma) [3, 8].

USCs typically occur in postmenopausal women with a median age of 70 years [4, 9]. UCSs are aggressive tumors, and approximately one-third of patients present with extrauterine disease at the time of diagnosis [4, 8, 10, 11]. The estimated 5-year survival for patients with USC is poor even when presenting at early stage, ranging from 40–75% in uterus confined disease compared with <35% for extrauterine disease [5, 12–14].

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) performed a comprehensive molecular characterization of uterine carcinosarcomas and identified extensive copy-number alterations and highly recurrent somatic mutations, the most frequently identified being TP53 mutation (91% of cases) [5]. DNA mismatch repair deficiency (MMR-D) has been found in a small subset of UCSs. The TCGA analysis found microsatellite instability (MSI) in 2 of 57 (4%) cases, Hoang et al. [6] demonstrated MMR-D in 4 of 67 (6%) cases and Jenkins et al [15] reported 4/103 (4%) cases with loss of expression of >1 MMR protein. The work of de Jong et al. [16] reported 12 of 29 (41%) cases with abnormal MMR staining, but this appeared to be an outlier. Little is known about the clinical, morphologic and molecular characteristics of MMR-D uterine carcinosarcomas. Our work, evaluating 276 UCS, is the largest study on this topic to date and was evaluate these features.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study was approved by the institutional research board. The pathology endometrial carcinomas database was reviewed to find all patients with endometrial carcinosarcomas. The patients in this database had been reflexively tested for mismatch repair protein expression by immunohistochemistry. We found 17 patients with MMR-D carcinosarcomas in the database over a 12-year period (2006–2018). Electronic medical records and pathology reports were reviewed to analyze clinical parameters (age at diagnosis, pathologic stage at diagnosis, clinical follow), pathologic variables and morphologic features (depth of myometrial invasion, LVI, histologic type and grade of carcinomatous and sarcomatous components, presence of homologous versus heterologous elements). Archival material was obtained from these cases; all hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tumor sections and MMR and p53 immunohistochemistry (IHC) slides were reviewed by two specialized gynecologic pathologists (DFD, SS). The clinical records were reviewed to include any pertinent information regarding previously performed targeted massively parallel sequencing and germline genetic testing. MLH1 promoter methylation studies was performed, as indicated.

For comparison, the clinicopathologic characteristics of a contemporaneous (2006–2018) cohort of MMR proficient USCs (n=259) were also recorded.

2.1. MLH1 promoter methylation

MLH1 promoter methylation was evaluated by pyrosequencing. Briefly, both tumor and normal DNA were extracted and bisulfite-treated using the EZ-DNA Methylation Kit (Cat#D5020, Zymo Research). A single PCR fragment spanning the target region was amplified and the degree of methylation of five CpG sites was analyzed in a single Pyrosequencing reaction (Qiagen). The PCR products (each 10 μl) were sequenced by pyrosequencing on a PyroMark Q24 Workstation (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The MLH1 hypermethylation levels were graded as positive if five of five CpG sites were methylated at ≥10%. In cases without confirmed MLH1 promoter methylation, multigene panel germline mutation testing was also performed separately as part of the clinical diagnostic work-up and according to standard methodologies.

2.2. Next generation sequencing (NGS)

Tumor and normal DNA samples were subjected to targeted massively parallel sequencing with the Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT) as previously described [17]. In brief, DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumors and patient-matched normal blood samples was extracted and sheared. Barcoded libraries from tumor and normal samples were captured, sequenced, and subjected to a custom pipeline to identify somatic mutations. The assay consisted of deep sequencing of all exons and selected introns of a custom 468 cancer-associated gene panel. All exons tested had a minimum depth of coverage of 100×. The alterations within the panel were all confirmed to be somatic, as mutations were called against the patient’s matched normal sample and any germline variants were filtered out by the pipeline.

2.2.1. Microsatellite instability score and mutational load

The algorithm MSIsensor was used to infer microsatellite instability (MSI) status from NGS data, as previously described, and samples with an MSIsensor score ≥10 were considered MSI-high [18, 19]. In addition, NGS assay for tumor profiling enables identification of a cutoff value for mutational load, providing a sensitive and specific (in the setting of endometrial cancer) means of screening for MMR-D. Based on prior work by Stadler et al. [20] using the 468-gene MSK-IMPACT assay, tumors with fewer than 20 somatic non-synonymous mutations are considered MMR proficient (MMR-P), and tumors with ≥ 20 non-synonymous somatic mutations are MMR-D.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Cohort

Seventeen (6.2%) cases of MMR-D UCS were found among 276 cases of UCS in our database during the study period.

3.2. Clinical Features

The median age of patients with MMR-D USC at diagnosis was 60 years (range 44–75 years; Table 1). At the time of diagnosis, 53% (9/17) of patients had stage I, 12% (2/17) stage II, 29% (5/17) stage III and 6% (1/17) stage IV disease (Table 1). The median follow-up was 34.1 months (range 1 month–12.6 years). At follow-up, 18% (3/17) had died of disease (DOD), 65% (11/17) showed no evidence of disease (NED) and 18% (3/17) were alive with disease (AWD).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinicopathologic characteristics of MMR-D uterine carcinosarcomas

| N=17 (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| ≤60 | 10 (59) | |

| >60 | 7 (41) | |

| Myometrium invasion | ||

| No/superficial | 3 (18) | |

| <50% | 5 (29) | |

| ≥50% | 9 (53) | |

| LVI | ||

| Present | 13 (76) | |

| Absent | 4 (24) | |

| Carcinomatous component subtype | ||

| Endometrioid | 6 (35) | |

| Non-endometrioid | 1 (6) | |

| Mixed carcinomas | 10 (59) | |

| Mixed carcinomas | ||

| CCC + LG endometrioid | 1 (10) | |

| UC + LG endometrioid carcinoma | 5 (50) | |

| CCC + HG endometrioid carcinoma | 1 (10) | |

| UC + HG endometrioid carcinoma | 3 (30) | |

| Sarcomatous component | ||

| Homologous | 11 (65) | |

| Heterologous | 6 (35) | |

| Chondrosarcomatous differentiation | 2 (33) | |

| Rhabdomyoblastic differentiation | 4 (67) | |

| FIGO Stage | ||

| I | 9 (53) | |

| II | 2 (12) | |

| III | 5 (29) | |

| IV | 1 (6) | |

| Recurrence | ||

| Yes | 2 (12) | |

| No | 15 (88) | |

| Follow-up | ||

| NED | 11 (65) | |

| AWD | 3 (18) | |

| DOD | 3 (18) | |

CCC: clear cell carcinoma; LG: low grade; UC: undifferentiated carcinoma; HG: high grade; NED: no evidence of disease; AWD: alive with disease; DOD: died of disease.

3.3. MMR proficient uterine carcinosarcomas

A total of 259 of uterine carcinosarcomas with retained MMR expression were identified during the same time period (2006–2018). The median age of patients was 66 years. At the time of diagnosis, 48% (123/259) of patients were stage I, 4% (11/259) stage II, 24% (62/259) stage III and 24% (63/259) stage IV. The median follow-up was 25.9 (range 0.4 month–12.3 years). At the time of follow-up, 39% (102/259) were NED, 39% (100/259) were DOD, 8% (20/259) were dead of other/or unknown (DOO), and 14% (37/259) were (AWD).

Comparing MMR-proficient and MMR-D USCs reveals differences in clinical outcomes between the groups. 36% of patients with MMR-D USCs had died of disease or were alive with disease, compared to 53% of patients with MMR-proficient USCs.

3.3. Histological Review

Of the 17 UCSs cases, the carcinomatous component was represented by mixed carcinoma in 10 cases (59%), endometrioid carcinoma in 6 cases (35%) and a non-endometrioid carcinoma in 1 case (6%) (Fig. 1). The mixed carcinomas were composed of low-grade endometrioid adenocarcinomas in 6 cases (1 case with clear cell carcinoma and 5 cases with undifferentiated carcinoma) and high-grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma in 4 cases (1 case with clear cell carcinoma and 3 cases with undifferentiated carcinoma). None of the cases showed a serous carcinoma component. The sarcomatous component was homologous in 11 cases (65%) and heterologous in 6 cases (35%). Of the tumors with heterologous stromal components, most were rhabdomyosarcomatous (67%) and chondrosarcomatous (33%). All of the sarcomatous elements were histologically high-grade.

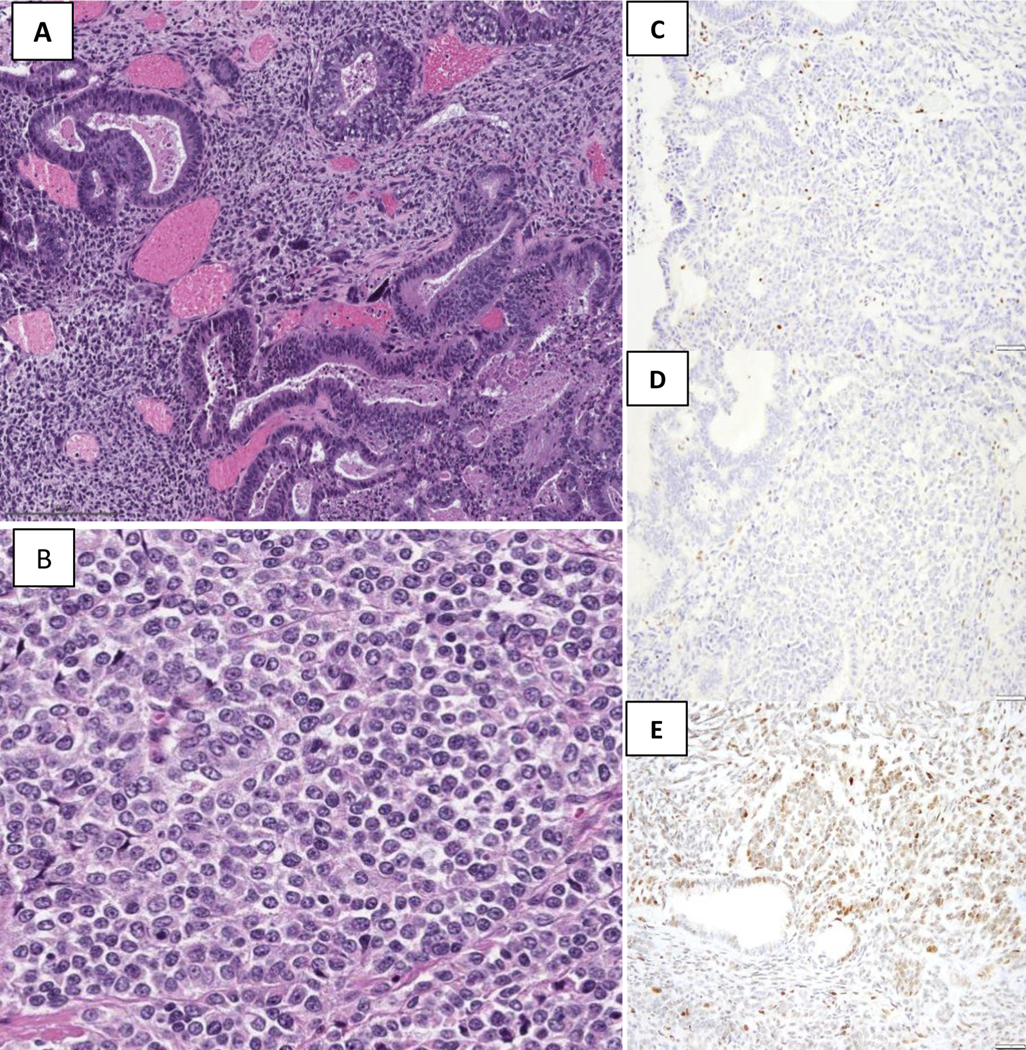

Figure 1.

The tumor shows distinct carcinomatous component, low-grade endometrioid and undifferentiated carcinoma [(A) and (B)] with high-grade spindle cell component. There is a concordant loss of MLH1 (C) and PMS2 (D) in both the epithelial and mesenchymal elements. A normal staining pattern is present within the background inflammatory cells, serving as internal positive controls. P53 shows a wild-type pattern (heterogeneous staining, E)

3.4. IHC Expression of MMR Proteins and p53

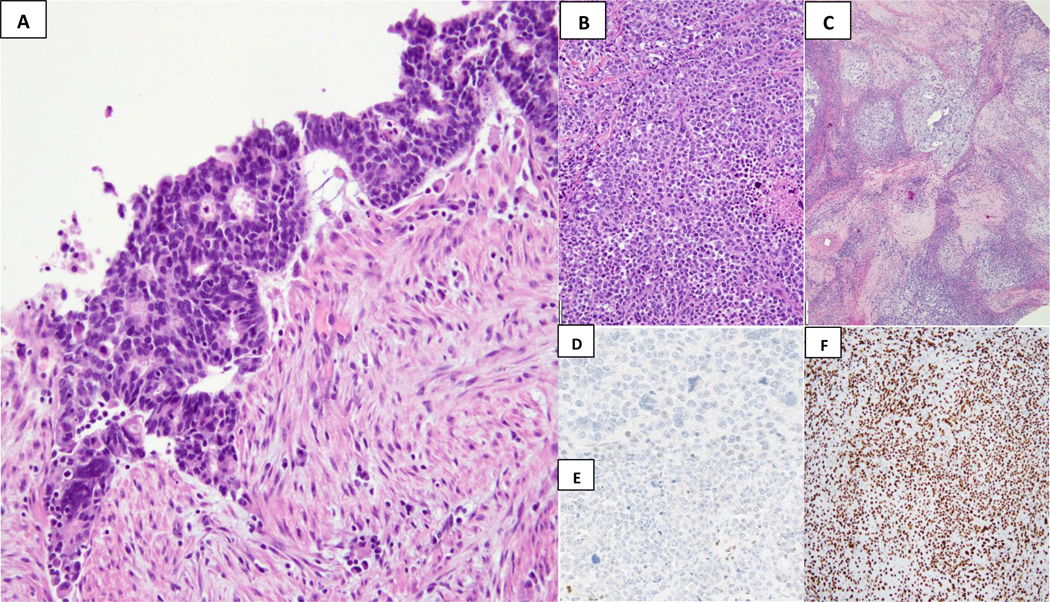

MMR protein loss of expression was observed in both the epithelial and mesenchymal elements (Table 2). Concurrent loss of MLH1 and PMS2 was observed in 65% (11/17) of cases (Fig. 1); loss of MSH2 and MSH6 was seen in 18% (3/17) of cases (Fig. 2), isolated loss of MSH6 was seen in 12% (2/17), and loss of PMS2 was present in only 6% (1/17) case. P53 immunohistochemical stain was performed in ten cases. A wild-type pattern (heterogenous staining) was seen 7 cases (70%) (Fig. 1), two cases showed an aberrant pattern (diffuse nuclear staining, Fig. 2) and 1 case was equivocal.

Table 2.

Immunohistochemical and molecular results in MMR deficient uterine carcinosarcomas

| Mismatch repair immunohistochemistry | N=17 (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| MLH1/PMS loss | 11 (65) | |

| MSH2/MSH6 loss | 3 (18) | |

| PMS2 loss only | 2 (12) | |

| MSH6 loss only | 1 (6) | |

| MLH1 Hypermethylation | N=11 | |

| Present | 8 (73) | |

| Germline testing | N=2 | |

| MLH1 deleterious germline mutation | 1 | |

| MSH2 deleterious germline mutation | 1 | |

| p53 immunohistochemistry | N=10 | |

| Wild-type | 7 (70) | |

| Aberrant (diffuse staining) | 2 (20) | |

| Equivocal | 1 (10) | |

| Next generation sequencing | N=8 | |

| Tumor mutational burden >20 | 7 (88) | |

| TP53 mutation | 2 (25) | |

| MSI sensor positive | 7 (88) | |

Figure 2.

Mismatch repair protein loss in an uterine carcinosarcoma. This biphasic tumor shows distinct carcinomatous component, low-grade endometrioid and undifferentiated carcinoma [(A) and (B)] and chondrosarcomatous areas (C). There is a concordant loss of MSH6 (D) and MSH2 (E) in both the epithelial and mesenchymal elements. A normal staining pattern is present within the background inflammatory cells, serving as internal positive controls. Aberrant (F) p53 pattern (10X, strongly positive nuclear staining)

Out of the eleven cases with MLH1/PMS2 loss by immunohistochemical stains, MLH1 promoter methylation was present in eight cases (73%). A multigene germline mutation panel testing was performed in three cases. A MLH1 deleterious germline mutation was found in one case with MLH1/PMS2 loss, a MSH2 deleterious germline mutation was found in one of the cases with MSH2/MSH6 loss and one case did not reveal any mutation. Next generation sequencing was performed in eight cases, and seven cases (88%) showed a hypermutated phenotype and were determined to be microsatellite high with a high MSI sensor score. Five of these cases (71%) had MLH1/PMS2 loss of expression with associated MLH1 hypermethylation; four cases displayed a p53 wild-type pattern, and one case showed an aberrant pattern (diffuse nuclear expression), however a TP53 mutation was not identified by sequencing. The 2 remaining cases (29%) showed loss of expression of MSH2/MSH6 by IHC. TP53 mutation was identified in the two cases, with one case also showing an aberrant p53 IHC pattern. No geographic staining was observed for MMR or p53.

4. DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that MMR-D uterine carcinosarcomas show clinical and morphologic features that differ from conventional UCSs. Uterine carcinosarcomas are rare aggressive tumors that typically affect post-menopausal women with a median age of 70 years [4, 9]. In our series, the median age for MMR-D UCSs was 60 years while the median age of patients with MMR-proficient USCs was 66. Clinically, 36% of patients with MMR-D USCs had died of disease or were alive with disease, compared to 53% of patients with MMR-proficient USCs.

Although the epithelial component in UCSs is commonly represented by serous carcinoma or high-grade adenocarcinomas with ambiguous morphology, the epithelial component of most UCSs in our study was high-grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma, and none of the cases had a component of serous carcinoma. Interestingly, a low-grade endometrioid adenocarcinoma component was seen in approximately one third of the cases, and was always admixed with a higher-grade component. UCS with solely low-grade components were not encountered.

The presence of heterologous sarcomatous component has been previously shown to be associated with worse outcomes [14, 21–26]. Kurnit et al [26]and Abdulfatah E et al. [14] recently reported that the presence of a rhabdomyosarcomatous component was significantly associated with worse overall survival (p=0.04 and p=0.0046, respectively). Ferguson et al. [24] also found that tumors with heterologous elements had significantly worse disease-free survival and 3-year overall survival (45% vs 93%) in FIGO stage I disease when compared with homologous carcinosarcomas. In our data, the sarcomatous component of MMR-D carcinosarcomas was not uncommonly heterologous (35%).

The endometrial TCGA [27] identified 4 molecular subtypes of endometrioid and serous endometrial cancer based on mutational burden, levels of copy number alterations and MSI status, including the POLE ultramutated group, MSI hypermutated group, the copy number-high (serous-like) (mutations in TP53) and the copy number-low (endometrioid) group, which correlated with progression-free survival. Stelloo et al [28, 29] demonstrated that ECs with POLE mutations and MSI showed better prognosis when compared with other ECs harboring TP53 mutations or no specific molecular profile (NSMP; ie copy number-low) and neither POLE mutation nor MSI. Bosse T. el al [30] also reported that MMR-D grade 3 endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinomas have better overall-survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) than p53 abnormal cases, and that MMR-D status remained as an independent prognostic factor for better RFS.

TP53 is the most recurrently mutated gene in UCSs [5] and p53 IHC has been shown to be 96% sensitive and 99% specific for TP53 gene mutation status in ovarian carcinomas [31, 32] and 95% specific in endometrial carcinomas [33]. The majority of carcinosarcomas show an aberrant or mutant p53 staining pattern that is concordant between the carcinomatous and sarcomatous components, and is more frequently observed in a non-endometrioid component [34]. In our cohort of MMR-D UCSs, TP53 mutation with aberrant p53 IHC was seen in two cases, while a discordant result was seen in one case with diffuse nuclear staining and no detectable TP53 mutation.

The presence of more than one molecular subtype, such as POLE mutant endometrial carcinomas with TP53 mutations/ aberrant p53 (characteristic of the copy number-high (serous-like) group) or MSI/ MMR-D endometrial cancers with TP53 mutations/ aberrant p53 have been described and represent ~3–4% of cases [29, 35–38]. In the setting of endometrial cancers of POLE or MSI subtype, which have a ultra- or hypermutator phenotype, TP53 mutations appear to be passenger mutations acquired during tumor progression, and the clinical outcomes are driven by the POLE or MMR-D status as opposed to the presence of TP53 mutations [36, 38].

In summary, we described a subgroup of UCSs with loss of DNA MMR protein expression and a high number of somatic mutations that appear to show a superior clinical course and distinct morphologic features when compared to traditional MMR-proficient UCSs. Based on our work, further studies are warranted to define the association of MMR-D UCSs with outcome. These data suggest that MMR IHC should be performed in UCSs, in particular in those with a low-grade endometrioid/undifferentiated component, for the identification of women with Lynch syndrome. In addition, given the agnostic approval for immunotherapy for MMR-D cancers, this information may inform treatment decisions the recurrent setting.

References:

- 1.Arrastia CD, et al. , Uterine carcinosarcomas: incidence and trends in management and survival. Gynecol Oncol, 1997. 65(1): p. 158–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamada SD, et al. , Pathologic variables and adjuvant therapy as predictors of recurrence and survival for patients with surgically evaluated carcinosarcoma of the uterus. Cancer, 2000. 88(12): p. 2782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murali R, et al. , High-grade Endometrial Carcinomas: Morphologic and Immunohistochemical Features, Diagnostic Challenges and Recommendations. Int J Gynecol Pathol, 2019. 38 Suppl 1: p. S40–S63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nucci MR C M, Oliva E et al., Mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumors, in WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs, C M. Kurman RJ, Herrington CS et al., Editor. 2014, International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Lyon, France. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherniack AD, et al. , Integrated Molecular Characterization of Uterine Carcinosarcoma. Cancer Cell, 2017. 31(3): p. 411–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoang LN, et al. , Immunohistochemical survey of mismatch repair protein expression in uterine sarcomas and carcinosarcomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol, 2014. 33(5): p. 483–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabban JT, et al. , Issues in the Differential Diagnosis of Uterine Low-grade Endometrioid Carcinoma, Including Mixed Endometrial Carcinomas: Recommendations from the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. Int J Gynecol Pathol, 2019. 38 Suppl 1: p. S25–S39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berton-Rigaud D, et al. , Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus review for uterine and ovarian carcinosarcoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2014. 24(9 Suppl 3): p. S55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bansal N, et al. , Uterine carcinosarcomas and grade 3 endometrioid cancers: evidence for distinct tumor behavior. Obstet Gynecol, 2008. 112(1): p. 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bland AE, et al. , A clinical and biological comparison between malignant mixed mullerian tumors and grade 3 endometrioid endometrial carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2009. 19(2): p. 261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantrell LA, Blank SV, and Duska LR, Uterine carcinosarcoma: A review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol, 2015. 137(3): p. 581–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schweizer W, et al. , Prognostic factors for malignant mixed mullerian tumors of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Pathol, 1990. 9(2): p. 129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vorgias G. and Fotiou S, The role of lymphadenectomy in uterine carcinosarcomas (malignant mixed mullerian tumours): a critical literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2010. 282(6): p. 659–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdulfatah E, et al. , Predictive Histologic Factors in Carcinosarcomas of the Uterus: A Multi-institutional Study. Int J Gynecol Pathol, 2019. 38(3): p. 205–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins TM, et al. , Mismatch Repair Deficiency in Uterine Carcinosarcoma: A Multi-institution Retrospective Review. Am J Surg Pathol, 2020. 44(6): p. 782–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Jong RA, et al. , Molecular markers and clinical behavior of uterine carcinosarcomas: focus on the epithelial tumor component. Mod Pathol, 2011. 24(10): p. 1368–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng DT, et al. , Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT): A Hybridization Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing Clinical Assay for Solid Tumor Molecular Oncology. J Mol Diagn, 2015. 17(3): p. 251–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Middha S, et al. , Reliable Pan-Cancer Microsatellite Instability Assessment by Using Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Data. JCO Precision Oncology, 2017(1): p. 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niu B, et al. , MSIsensor: microsatellite instability detection using paired tumor-normal sequence data. Bioinformatics, 2014. 30(7): p. 1015–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stadler ZK, et al. , Reliable Detection of Mismatch Repair Deficiency in Colorectal Cancers Using Mutational Load in Next-Generation Sequencing Panels. J Clin Oncol, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverberg SG, et al. , Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed mesodermal tumor) of the uterus. A Gynecologic Oncology Group pathologic study of 203 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol, 1990. 9(1): p. 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Major FJ, et al. , Prognostic factors in early-stage uterine sarcoma. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer, 1993. 71(4 Suppl): p. 1702–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwasa Y, et al. , Prognostic factors in uterine carcinosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 25 patients. Cancer, 1998. 82(3): p. 512–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson SE, et al. , Prognostic features of surgical stage I uterine carcinosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol, 2007. 31(11): p. 1653–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuo K, et al. , Significance of histologic pattern of carcinoma and sarcoma components on survival outcomes of uterine carcinosarcoma. Ann Oncol, 2016. 27(7): p. 1257–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurnit KC, et al. , Prognostic factors impacting survival in early stage uterine carcinosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol, 2019. 152(1): p. 31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N., et al. , Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature, 2013. 497(7447): p. 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stelloo E, et al. , Refining prognosis and identifying targetable pathways for high-risk endometrial cancer; a TransPORTEC initiative. Mod Pathol, 2015. 28(6): p. 836–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stelloo E, et al. , Improved Risk Assessment by Integrating Molecular and Clinicopathological Factors in Early-stage Endometrial Cancer-Combined Analysis of the PORTEC Cohorts. Clin Cancer Res, 2016. 22(16): p. 4215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosse T, et al. , Molecular Classification of Grade 3 Endometrioid Endometrial Cancers Identifies Distinct Prognostic Subgroups. Am J Surg Pathol, 2018. 42(5): p. 561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobel M, et al. , Optimized p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate predictor of TP53 mutation in ovarian carcinoma. J Pathol Clin Res, 2016. 2(4): p. 247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlson JW and Nastic D, High-Grade Endometrial Carcinomas: Classification with Molecular Insights. Surg Pathol Clin, 2019. 12(2): p. 343–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh N, et al. , p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate surrogate for TP53 mutational analysis in endometrial carcinoma biopsies. J Pathol, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buza N. and Tavassoli FA, Comparative analysis of P16 and P53 expression in uterine malignant mixed mullerian tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol, 2009. 28(6): p. 514–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talhouk A, et al. , A clinically applicable molecular-based classification for endometrial cancers. Br J Cancer, 2015. 113(2): p. 299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talhouk A, et al. , Molecular classification of endometrial carcinoma on diagnostic specimens is highly concordant with final hysterectomy: Earlier prognostic information to guide treatment. Gynecol Oncol, 2016. 143(1): p. 46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hussein YR, et al. , Clinicopathological analysis of endometrial carcinomas harboring somatic POLE exonuclease domain mutations. Mod Pathol, 2015. 28(4): p. 505–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leon-Castillo A, et al. , Clinicopathological and molecular characterisation of ‘multiple-classifier’ endometrial carcinomas. J Pathol, 2020. 250(3): p. 312–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]