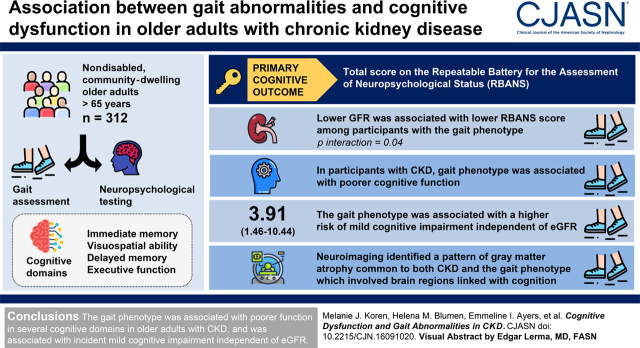

Visual Abstract

Keywords: geriatric nephrology, chronic kidney disease, cognitive dysfunction, gait

Abstract

Background and objectives

Cognitive impairment is a major cause of morbidity in CKD. We hypothesized that gait abnormalities share a common pathogenesis with cognitive dysfunction in CKD, and therefore would be associated with impaired cognitive function in older adults with CKD, and focused on a recently defined gait phenotype linked with CKD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Gait assessments and neuropsychological testing were performed in 312 nondisabled, community-dwelling older adults (aged ≥65 years). A subset (n=115) underwent magnetic resonance imaging. The primary cognitive outcome was the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) total scale score. Associations with cognitive function were tested using multivariable linear regression and nearest-neighbor matching. The risk of developing mild cognitive impairment syndrome was assessed using Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

Lower eGFR was associated with lower RBANS score only among participants with the gait phenotype (P for interaction =0.04). Compared with participants with neither CKD nor the gait phenotype, adjusted RBANS scores were 5.4 points (95% confidence interval, 1.8 to 9.1) lower among participants with both, who demonstrated poorer immediate memory, visuospatial ability, delayed memory, and executive function. In a matched analysis limited to participants with CKD, the gait phenotype was similarly associated with lower RBANS scores (−6.9; 95% confidence interval, −12.2 to −1.5). Neuroimaging identified a pattern of gray matter atrophy common to both CKD and the gait phenotype involving brain regions linked with cognition. The gait phenotype was associated with higher risk of mild cognitive impairment (hazard ratio, 3.91; 95% confidence interval, 1.46 to 10.44) independent of eGFR.

Conclusions

The gait phenotype was associated with poorer function in a number of cognitive domains among older adults with CKD, and was associated with incident mild cognitive impairment independent of eGFR. CKD and the gait phenotype were associated with a shared pattern of gray matter atrophy.

Introduction

Patients with CKD have high rates of cognitive impairment (1). This places them at greater risk of falls, institutionalization, and death (2,3). The pathogenesis of cognitive impairment in CKD remains incompletely understood, and the ability to identify individuals at high risk of cognitive decline is limited (4). Therefore, it is important to better elucidate underlying mechanisms, and to identify novel markers for cognitive impairment in this patient population.

One risk factor for cognitive impairment in the elderly is gait dysfunction. In the general elderly, gait abnormalities are associated with the development of both cognitive decline and non-Alzheimer dementia, especially vascular dementia (5,6). Furthermore, cognition and gait are linked by a common neural substrate: anatomic areas that mediate them overlap, and brain structure differs in patients with both impaired cognition and gait abnormalities compared with patients with neither or with gait disturbance alone. For example, a predementia syndrome characterized by slow gait and cognitive complaints, called the motoric cognitive risk syndrome, is associated with gray matter atrophy not only in brain regions involved in the motoric aspects of gait, but also those responsible for its cognitive control (7).

Surprisingly, with the exception of a study that used gait speed as the sole metric of gait function (8), the relationship between cognition and gait abnormalities has not been explored in nondialysis-dependent CKD. This is a notable gap because the cognitive domains affected in CKD significantly overlap those affected in adults with gait impairment; for example, executive function, attention, and language are impaired in both conditions (4,9 –13).

Recently, our group identified disturbances in gait among older adults with nondialysis-dependent CKD (14). These did not fit any previously defined neurologic gait, but shared characteristics with unsteady gait; although present in older adults with and without CKD, they were of substantially greater severity in CKD, and associated with larger abnormalities in quantitative gait parameters. Further, they translated into a unique, clinically detectable gait phenotype that was associated with a higher risk of falls only among individuals with CKD (14). We hypothesized that gait abnormalities would be associated with cognitive impairment in people with CKD, and focused on this newly defined gait phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Participants were enrolled in the Central Control of Mobility in Aging (CCMA) study, which aimed to define neurologic determinants of mobility in aging. Potential participants 65 and older were identified from population lists of Westchester County, New York, between June 2011 and October 2017. Exclusion criteria were inability to speak English, inability to ambulate independently, dementia, vision and/or hearing impairment that would preclude participants from completing neuropsychological testing, current or history of neurologic or psychiatric disorders, recent or anticipated medical procedures affecting mobility, and current hemodialysis. Participants completed a structured telephone interview to assess eligibility, and to rule out dementia using cognitive screeners (15 –17). Individuals who passed the interview were invited to in-person visits, during which they received neuropsychological, cognitive, and mobility assessments and a standardized neurologic examination. Re-evaluation occurred annually. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and all participants provided written informed consent.

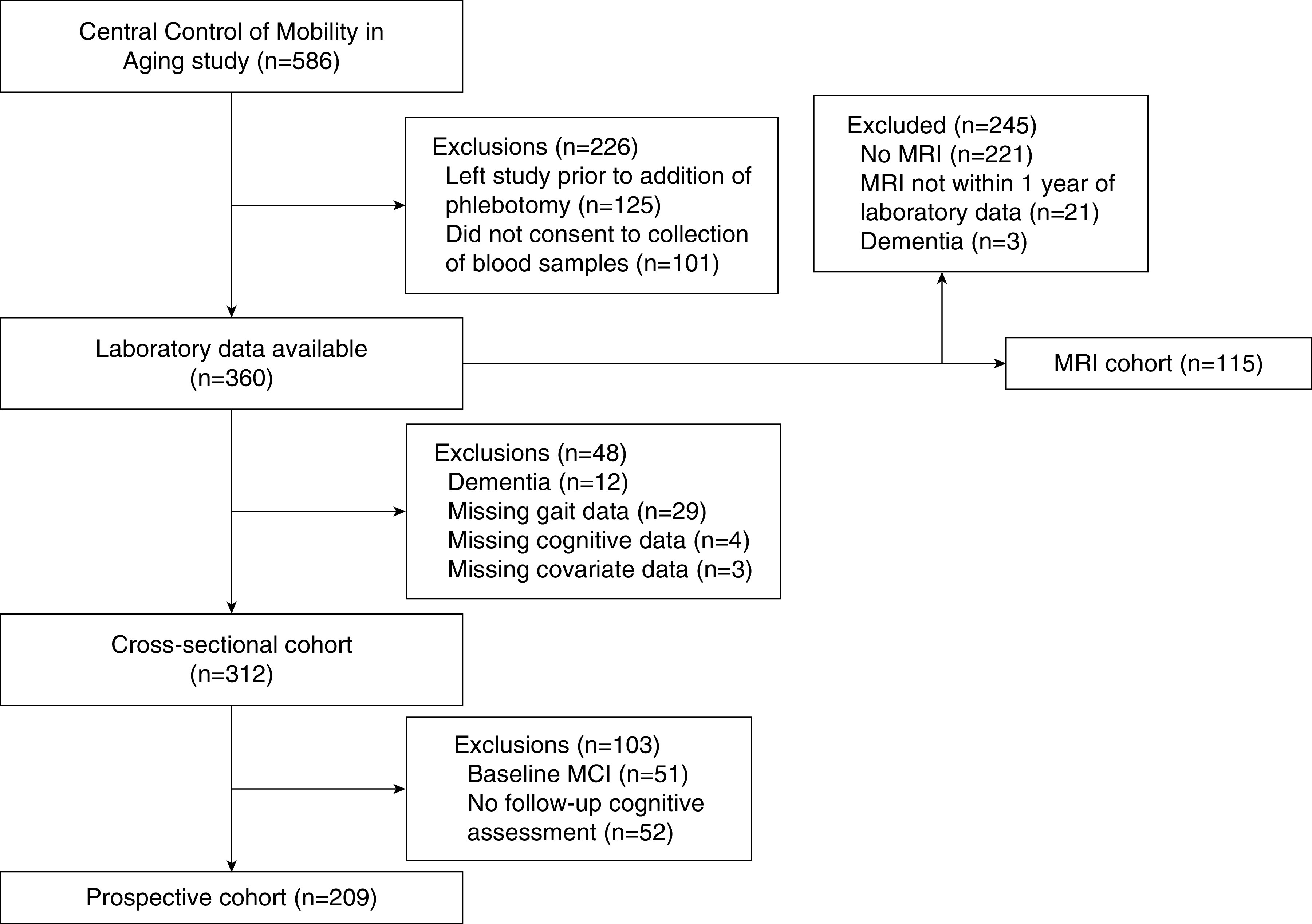

The CCMA study began collecting blood samples from consenting participants in July 2013 (14). This analysis includes data collected through September 2018, at which point 360 participants had laboratory data available (Figure 1). Participant characteristics did not differ between those with and without blood samples (14). We used gait parameters, comorbidity and medication data, and neuropsychological testing from the same visit in which blood was drawn for laboratory testing. Exclusion criteria for our study included dementia (n=12) and missing data for gait (n=29), cognitive assessment (n=4), or covariates of interest (n=3). The final cohort included 312 participants.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study participation. MCI, mild cognitive impairment syndrome; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Study Design

Demographic information, medications, and comorbidities (including physician-diagnosed lung diseases, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, neurologic diseases, depression, and arthritis) were obtained through structured medical questionnaires. Cardiovascular disease was defined as history of myocardial infarction, stent or angioplasty, coronary artery bypass graft, congestive heart failure, or physician-diagnosed angina. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (18). eGFR was calculated using the creatinine-based CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation (19). Serum creatinine was quantified using a modified kinetic Jaffé reaction. Participants with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were considered to have CKD (20).

Gait Assessment

Gait was assessed clinically for overall gait phenotype and spatiotemporal gait characteristics. Assessment took place during a standard neurologic examination by study clinicians who were blinded to participants’ CKD status and laboratory results. Participants were observed walking up and down a well-lit hallway at their normal pace. Study clinicians observed participants for gait pattern, either neurologic (hemiparetic, neuropathic, ataxic, frontal, parkinsonian, spastic, or unsteady) or non-neurologic (e.g., secondary to arthritis or cardiac disease) (5). Inter-rater reliability for identifying neurologic gait is good, with percent agreement ranging from 0.6 to 0.8 (5,21). Participants’ gaits were further characterized by the presence or absence of individual, spatiotemporal components. The new gait phenotype was defined as the presence of short steps and/or marked sway or loss of balance during straight or tandem walking (14). Gait speed was measured using a GAITRite 20-foot computerized walkway (CIR Systems, Havertown, PA). Slow gait speed was defined as <0.8 m/s (22).

Cognitive Assessment

Neuropsychological Testing.

Participants underwent annual neuropsychological testing. Trained research assistants conducted these assessments under the supervision of a neuropsychologist. The primary measure for cognitive performance was the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) total scale score. The RBANS is a validated set of neuropsychological tests that provides scaled scores for global cognition and five subdomains: immediate memory, visuospatial/constructional, language, attention, and delayed memory (23). Higher scores on total scale and individual indexes represent better performance. Each score is calculated with mean 100 and SD 15, on the basis of a normative sample. Additional neuropsychological testing included the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (24), Controlled Oral Word Fluency test for phonemic and semantic fluency (25), Trail Making Test (TMT) Parts A and B (26), Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) (27), and Boston Naming Test (28). These contributed to the assessment of executive function (TMT, DSST, and Controlled Oral Word Fluency test) and provided additional measurements for the domains covered in the RBANS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Neuropsychological tests by cognitive domain

| Neuropsychological Tests | Language | Visuospatial/Constructional | Attention | Executive Function | Immediate Memory | Delayed Memory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBANS tests | Picture naming | Figure copy | Digit span | List learning | Figure recall | |

| Semantic fluency | Line orientation | Coding (approximately DSST) | Story memory | List recall | ||

| List recognition | ||||||

| Story recall | ||||||

| Other tests | BNT | TMT A | TMT A | TMT B | FCSRT | |

| Category fluency | TMT B | TMT B | TMTΔ | BNT | ||

| Letter fluency | DSST | DSST | DSST | DSST | ||

| Letter fluency | ||||||

| Category fluency |

RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; DSST, Digit Symbol Substitution Test; BNT, Boston Naming Test; TMT A, Trail Making Test Part A; TMT B, Trail Making Test Part B; FCSRT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test; TMTΔ, Trail Making Test Δ (Part B minus Part A).

Clinical Diagnoses.

Assessment for mild cognitive impairment syndrome and dementia also occurred annually. Diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment and dementia were prospectively determined using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria (29), at consensus case conferences attended by a minimum of one neuropsychologist and one neurologist. Criteria for mild cognitive impairment included the presence of subjective cognitive complaints and performance of ≥1.5 SDs below age- and education-appropriate norms on relevant cognitive tests, but without impairment in activities of daily living or dementia diagnosis (30,31).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Acquisition and Preprocessing

Standard three-dimensional, T1-weighted (structural) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images were obtained with a Philips 3T MRI scanner in a subset of CCMA participants. Eligibility criteria for the MRI study were identical to the main study, with the addition of MRI contraindications such as permanent magnetic metal implants and pacemakers. Neuroimaging analyses were performed in a subset of participants who underwent MRI within 1 year of the baseline laboratory visit (Figure 1; n=115). Each structural MRI image was analyzed using voxel-based morphometry and segmented into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. Only gray matter probability maps were used in these analyses. Full details are provided in Supplemental Appendix 1 (32 –38).

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics were summarized by CKD and gait phenotype status. Associations with cognitive performance were examined using linear regression models. Models were adjusted for covariates thought a priori to be potential confounders of the effects of kidney function and gait on cognition, including age, sex, race, number of comorbidities, history of diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, number of medications, years of education, and depressive symptoms as assessed by the GDS. Models were additionally adjusted for eGFR as indicated. As no cognitive domain was missing data from more than five participants, complete-case analyses were performed. Effect modification was tested using multiplicative interaction terms.

To estimate the association of the gait phenotype with cognitive function, nearest-neighbor matching was performed separately within the CKD and non-CKD subsets of the cohort. We required exact matching on eGFR, defined the Mahalanobis distance by the covariates listed above, and performed large-sample bias correction using a linear function of age, GDS score, and eGFR (39). To ensure adequate overlap for matching, these analyses were restricted to participants with eGFR ≥40 and ≤95 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

The risk of developing mild cognitive impairment syndrome associated with the gait phenotype was assessed using Cox proportional hazard models, adjusted for the aforementioned covariates and eGFR. Those with a prevalent diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment were excluded. Time was calculated from blood draw date to the first visit at which mild cognitive impairment was diagnosed or to the last follow-up encounter, whichever came first. No participant developed incident dementia during follow-up without an intervening mild cognitive impairment diagnosis. Visual inspection of log-log plots was used to verify the proportional hazards assumption. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp., College Station, TX). Statistical significance was determined using P<0.05.

Multivariate Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analyses

Multivariate MRI analyses were performed to identify gray matter covariance patterns or “networks” associated with CKD and the gait phenotype, in two separate models. Both models were adjusted for age, sex, race, number of comorbidities, mild cognitive impairment syndrome, and total intracranial volume. Analyses were implemented with the principal components analysis suite (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/gcva_pca) (36,40). Additional details are provided in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The median for age was 76 (interquartile range [IQR], 73–82) years, and the median for eGFR was 65 (IQR, 50–75) ml/min per 1.73 m2; the mean RBANS total scale score was 93.1±12.2, and mean gait speed was 1.0±0.2 m/s. Overall, 40% (n=127) of participants had CKD, and 53% (n=168) met criteria for the gait phenotype. Participants with CKD and the gait phenotype were older and had higher number of comorbidities and prevalence of cardiovascular disease and mild cognitive impairment than other participants (Table 2). There were no meaningful differences across categories in the prevalence of diabetes, history of stroke or head trauma, or GDS scores. Among participants with CKD, eGFR was lower in the group with the gait phenotype than the group without. Slow gait speed, unsteady gait, and other neurologic gaits were more common among participants with the gait phenotype than those without. Among those with the gait phenotype, 30% (n=50) had unsteady gait; conversely, among those with unsteady gait, nearly all (n=50 out of 51) met criteria for the gait phenotype.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics by CKD and gait phenotype status

| Characteristic | No CKD | CKD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Gait Phenotype, n=109 | Gait Phenotype, n=77 | No Gait Phenotype, n=38 | Gait Phenotype, n=88 | |

| Age, yr | 73 (71–77) | 77 (74–82) | 76 (73–81) | 81 (76–86) |

| Women, n (%) | 61 (56) | 42 (55) | 19 (50) | 47 (53) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 83 (76) | 59 (77) | 33 (87) | 69 (78) |

| Black | 22 (20) | 16 (21) | 5 (13) | 17 (19) |

| Other | 4 (4) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| High school or less | 28 (26) | 24 (31) | 10 (26) | 29 (33) |

| College (some) | 47 (43) | 33 (43) | 18 (47) | 40 (45) |

| Postgraduate | 34 (31) | 20 (26) | 10 (26) | 19 (22) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, n=301 | 26.8 (23.0–31.3) | 26.6 (23.7–31.9) | 28.0 (25.5–30.8) | 28.7 (24.9–32.2) |

| Ever regular smoker, n (%), n=310 | 55 (50) | 39 (52) | 23 (61) | 48 (55) |

| No. of medications, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 6 (6) | 5 (6) | 4 (11) | 3 (3) |

| 1 | 39 (36) | 23 (30) | 16 (42) | 21 (24) |

| 2 | 37 (34) | 32 (42) | 7 (18) | 27 (31) |

| ≥3 | 27 (25) | 17 (22) | 11 (29) | 37 (42) |

| Comorbidities, Global Health Score, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 21 (19) | 14 (18) | 5 (13) | 6 (7) |

| 1 | 33 (30) | 25 (32) | 13 (34) | 23 (26) |

| 2 | 34 (31) | 26 (34) | 8 (21) | 40 (45) |

| ≥3 | 21 (19) | 12 (16) | 12 (32) | 19 (22) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 17 (16) | 13 (17) | 10 (26) | 17 (19) |

| Hypertension, n (%), n=311 | 62 (57) | 45 (58) | 23 (61) | 59 (68) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%), n=311 | 67 (62) | 48 (62) | 23 (61) | 50 (57) |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 9 (8) | 9 (10) | 6 (16) | 22 (25) |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n (%), n=308 | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Head trauma, n (%), n=304 | 14 (13) | 10 (14) | 7 (19) | 8 (9) |

| Depression requiring treatment, n (%), n=311 | 17 (16) | 5 (6) | 6 (16) | 8 (9) |

| Geriatric Depression Scale score | 4 (1–6) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–5) | 4 (2–7) |

| Cognitive status, n (%) | ||||

| Normal | 95 (87) | 66 (86) | 32 (84) | 68 (77) |

| MCI | 14 (13) | 11 (14) | 6 (16) | 20 (23) |

| BP systolic, mm Hg, n=306 | 131±15 | 131±15 | 128±12 | 126±14 |

| BP diastolic, mm Hg, n=306 | 78±8 | 79±8 | 78±7 | 75±8 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m 2 | 74 (68–83) | 72 (65–82) | 52 (44–56) | 44 (36–53) |

| ≥75, n (%) | 49 (45) | 32 (42) | 0 | 0 |

| 60–<75, n (%) | 60 (55) | 45 (58) | 0 | 0 |

| 45–<60, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 28 (74) | 43 (49) |

| 30–<45, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 10 (26) | 34 (39) |

| <30, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (13) |

| Gait speed, m/s, n=311 | 1.1±0.2 | 0.9±0.2 | 1.0±0.2 | 0.8±0.2 |

| Slow gait speed, n (%), n=311 | 8 (7) | 15 (19) | 6 (16) | 38 (43) |

| Neurologic gait, n (%) | 6 (6) | 16 (21) | 4 (11) | 17 (19) |

| Unsteady gait, n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 22 (29) | 0 (0) | 28 (32) |

CKD is defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Continuous variables reported as mean±SD or median (interquartile range). MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Associations of eGFR and Gait with Cognitive Function

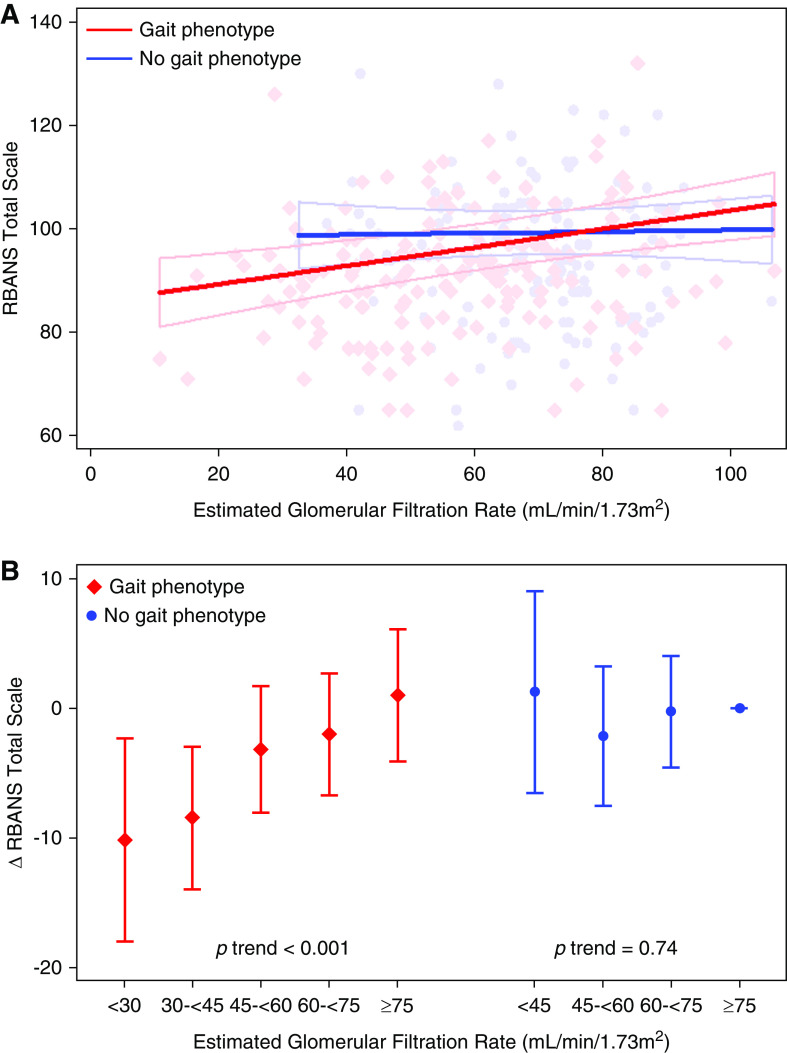

Gait phenotype status modified the association of eGFR with RBANS total scale score. Lower eGFR was associated with poorer RBANS score among participants with the gait phenotype (−1.8 points per 10 ml/min per 1.3 m2 lower eGFR; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], −0.9 to −2.8 ), but not those without (0.2 points per 10 ml/min per 1.3 m2 lower eGFR; 95% CI, −1.2 to 1.5 ) (Figure 2A; P for interaction =0.04, testing effect modification of eGFR-RBANS association by gait phenotype). Modeling eGFR within categories produced similar results, demonstrating a linear association with lower RBANS score only among participants with the gait phenotype (Figure 2B). The association of eGFR with RBANS score was unchanged after excluding participants with eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (−1.8 points per 10 ml/min per 1.3 m2 lower eGFR among participants with the gait phenotype; 95% CI, −0.7 to −2.9 ). In contrast, the presence of a neurologic gait phenotype (excluding unsteady gait, because of taxonomic overlap with the newly defined gait phenotype [14]) did not modify the association of eGFR with RBANS score (P for interaction =0.71), nor did the presence of slow gait speed (P for interaction =0.39). Further, after excluding participants with a neurologic gait, similar effect modification by the gait phenotype was observed (P for interaction =0.04).

Figure 2.

Effect modification of eGFR-RBANS association by gait status. (A) Scatterplots and linear model fit of association of eGFR with RBANS total scale score stratified by the presence of the gait phenotype (P for interaction =0.04). (B) Difference in RBANS total scale score by eGFR category, stratified by the presence of the gait phenotype. Reference group is participants with eGFR ≥75 ml/min per 1.73 m2 without the gait phenotype. RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status.

Association of Gait Phenotype with Cognitive Function

Next, we quantified differences in cognitive function by gait phenotype and CKD status. Compared with participants without CKD and without the gait phenotype, participants with CKD and the gait phenotype exhibited worse performance on the RBANS total scale and subdomains for immediate memory, visuospatial ability, and delayed memory (Supplemental Table 1). These differences persisted after multivariable adjustment (Table 3). Additional adjustment for eGFR largely attenuated these estimates, consistent with lower eGFR lying on the same causal pathway as the gait phenotype and poorer cognitive function (Table 3). Among participants with CKD without the gait phenotype, estimates were substantially smaller in magnitude and not statistically significant (Table 3). To examine the independent association of gait phenotype status with cognitive function among participants with CKD, we used a matched analysis because of imbalances in eGFR: in this smaller subset, the gait phenotype was associated with lower scores on the RBANS total scale and subdomains for immediate memory, visuospatial ability, and delayed memory (Table 4).

Table 3.

Association of gait phenotype and CKD status with cognitive function a

| No CKD | CKD | CKD (with eGFR Adjustment) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Test | + Gait Phenotype (Coefficient) | No Gait Phenotype (Coefficient) | + Gait Phenotype (Coefficient) | No Gait Phenotype (Coefficient) | + Gait Phenotype (Coefficient) |

| RBANS | |||||

| Total scale | −0.4 (−3.8 to 3.0) | −0.9 (−5.2 to 3.3) | −5.4 (−9.1 to −1.8) | 2.0 (−3.3 to 7.3) | −1.9 (−7.2 to 3.4) |

| Subdomain scores | |||||

| Immediate memory | 0.7 (−2.8 to 4.1) | −2.7 (−7.1 to 1.7) | −5.8 (−9.5 to −2.0) | 1.7 (−3.8 to 7.1) | −0.5 (−6.0 to 4.9) |

| Visuospatial/constructional | −3.4 (−7.3 to 0.4) | −1.3 (−6.1 to 3.6) | −7.2 (−11.3 to −3.1) | −0.3 (−6.3 to 5.8) | −6.0 (−12.0 to 0.08) |

| Language | 0.8 (−2.3 to 3.9) | 0.2 (−3.7 to 4.0) | 1.1 (−2.2 to 4.4) | 1.6 (−3.3 to 6.4) | 2.9 (−2.0 to 7.7) |

| Attention | −0.2 (−4.2 to 3.8) | −1.9 (−7.0 to 3.1) | −3.2 (−7.5 to 1.1) | 0.5 (−5.8 to 6.8) | −0.2 (−6.5 to 6.1) |

| Delayed memory | 0.4 (−2.9 to 3.6) | 0.3 (−3.8 to 4.5) | −4.6 (−8.1 to −1.1) | 2.3 (−2.9 to 7.5) | −2.2 (−7.4 to 2.9) |

| Individual cognitive tests | |||||

| FCSRT, recall score, n=307 | −0.3 (−2.2 to 1.6) | −0.6 (−3.0 to 1.8) | −1.3 (−3.3 to 0.8) | 1.6 (−1.4 to 4.6) | 1.4 (−1.6 to 4.4) |

| Letter fluency, z-score | −0.06 (−0.4 to 0.3) | −0.07 (−0.5 to 0.4) | −0.4 (−0.8 to –0.02) | −0.2 (−0.8 to 0.3) | −0.6 (−1.1 to −0.03) |

| Category fluency, z-score | −0.2 (−0.6 to 0.1) | −0.3 (−0.8 to 0.1) | −0.5 (−0.9 to −0.1) | −0.2 (−0.8 to 0.4) | −0.4 (−1.0 to 0.2) |

| Trail Making Test A, z-score | −0.07 (−0.3 to 0.2) | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.5) | −0.3 (−0.5 to 0.01) | 0.05 (−0.4 to 0.4) | −0.4 (−0.8 to 0.00) |

| Trail Making Test B, z-score, n=307 | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.2) | −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.3) | −0.4 (−0.7 to −0.01) | −0.2 (−0.7 to 0.3) | −0.5 (−1.0 to 0.02) |

| Trail Making Test ∆ b , seconds n=307 | 6.6 (−9.0 to 22.1) | 10.0 (−9.4 to 29.5) | 13.7 (−3.3 to 30.7) | 12.0 (−12.2 to 36.3) | 16.1 (−8.3 to 40.5) |

| Digit Symbol Substitution Test, scaled score | −0.1 (−0.9 to 0.7) | 0.07 (−1.0 to 1.1) | −1.0 (−1.8 to −0.07) | 0.4 (−0.9 to 1.7) | −0.6 (−1.9 to 0.7) |

| Boston Naming Test, z-score, n=308 | 0.04 (−0.2 to 0.3) | 0.06 (−0.3 to 0.4) | 0.04 (−0.3 to 0.3) | 0.2 (−0.3 to 0.6) | 0.2 (−0.3 to 0.6) |

All models adjusted for age, sex, race, number of comorbidities, number of medications, history of diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, education, and Geriatric Depression Scale. CKD (with eGFR adjustment) presents results for CKD groups from model that additionally included eGFR as covariate. Results shown are coefficients and 95% confidence intervals. RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; FCSRT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test.

Reference group is participants with no CKD and no gait phenotype. CKD defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (n=312).

Trail Making Test ∆ is defined as Trail Making Test Part B score minus Trail Making Test Part A score.

Table 4.

Association of gait phenotype with cognitive function by CKD status a

| Cognitive Test | No CKD, n=181; Coefficient (95% CI) | CKD, n=96; Coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| RBANS | ||

| Total scale | 0.6 (−3.6 to 4.9) | −6.9 (−12.2 to −1.5) |

| Subdomain scores | ||

| Immediate memory | 1.9 (−2.4 to 6.2) | −4.8 (−9.6 to −0.01) |

| Visuospatial/constructional | −3.3 (−7.5 to 1.0) | −8.2 (−14.4 to −1.9) |

| Language | 1.1 (−2.9 to 5.0) | 0.3 (−3.6 to 4.1) |

| Attention | −0.8 (−5.1 to 3.5) | −4.5 (−10.7 to 1.7) |

| Delayed memory | 1.8 (−2.2 to 5.8) | −5.9 (−10.9 to −0.8) |

| Individual cognitive testsb | ||

| FCSRT, recall score | −0.2 (−2.5 to 2.1) | 0.6 (−2.2 to 3.4) |

| Letter fluency, z-score | 0.2 (−0.2 to 0.5) | −0.6 (−1.1 to −0.2) |

| Category fluency, z-score | −0.09 (−0.5 to 0.3) | −0.4 (−0.9 to 0.1) |

| Trail Making Test A, z-score | 0.02 (−0.2 to 0.3) | −0.6 (−0.9 to −0.3) |

| Trail Making Test B, z-score | −0.2 (−0.5 to 0.2) | −0.6 (−1.1 to −0.1) |

| Trail Making Test ∆ c , seconds | 9.9 (−6.9 to 26.6) | 18.4 (−6.7 to 43.5) |

| Digit Symbol Substitution Test, scaled score | 0.2 (−0.7 to 1.2) | −2.2 (−3.5 to −0.9) |

| Boston Naming Test, z-score | 0.05 (−0.3 to 0.4) | 0.002 (−0.4 to 0.4) |

Nearest-neighbor matching analyses required exact matching on eGFR; Mahalanobis distance defined by age, sex, race, number of comorbidities, number of medications, history of diabetes, history of cardiovascular disease, education, and Geriatric Depression Scale; large-sample bias correction performed using a linear function of age, GDS score, and eGFR. To ensure adequate overlap for matching, analyses were restricted to participants with eGFR ≥40 and ≤95 ml/min per 1.73 m2. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; FCSRT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test.

Reference groups within the no CKD and CKD groups are participants without gait phenotype. CKD defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Sample size included in RBANS analyses indicated above for the no CKD and CKD groups. Two participants without CKD did not have a match. Median (interquartile range) number of matches: no CKD, 10 (5–13); CKD, 8 (6–10).

Sample sizes: no CKD group: FCSRT, n=180; Trail Making Test B, n=176; Trail Making Test ∆, n=176; Boston Naming Test, n=177; all else, n=181. CKD group: FCSRT, n=94; all else, n=96.

Trail Making Test ∆ is defined as Trail Making Test Part B score minus Trail Making Test Part A score.

We also examined participants’ performance on an additional battery of cognitive tests (see Table 1 for cognitive domains addressed by each test). Performance on a number of tests was poorest among participants with CKD and the gait phenotype (Supplemental Table 1). After multivariable adjustment, the presence of both CKD and the gait phenotype was associated with poorer performance on tests of executive function, visuospatial ability, attention, language, and immediate memory, including Letter Fluency, Category Fluency, TMT Part B, and the DSST (Table 3). These were attenuated by eGFR adjustment (Table 3). In a matched analysis among participants with CKD, the gait phenotype was also associated with poorer performance in Letter Fluency, the DSST, and TMT Parts A and B (Table 4).

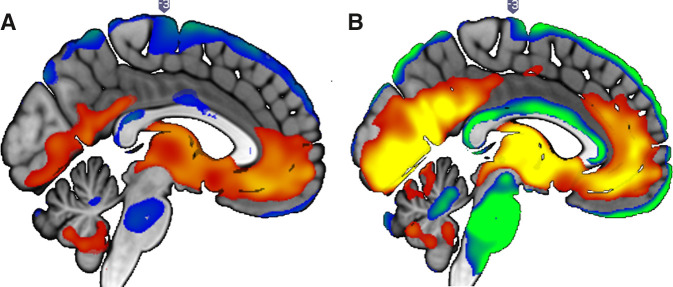

CKD, Gait Phenotype, and Neuroimaging Outcomes

We next sought to determine whether the gait phenotype shared a common neuroanatomical substrate with CKD. Participant characteristics by CKD status for the neuroimaging analyses are shown in Table 5. The gray matter volume covariance pattern associated with the gait phenotype exhibited substantial overlap with that of CKD (Figure 3, Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). The pattern associated with CKD was composed of two principal components that accounted for 14% of the variance. Regions with relatively less atrophy (i.e., positively weighted) included supplementary motor, cerebellar (VIIIA), pallidum, inferior occipital, and temporal pole regions. Regions with relatively more atrophy (i.e., negatively weighted) included cerebellar (Crus II, IX, and VIIB), calcarine sulcus and middle occipital, inferior and middle temporal, superior and inferior parietal, precentral, and frontal (middle and inferior) regions. The gray matter volume covariance pattern associated with the gait phenotype was composed of one principal component that accounted for 23% of the variance. Positively weighted regions included superior frontal, parahippocampal, and caudate regions. Negatively weighted regions included Rolandic opercular; superior, middle, and inferior frontal; inferior temporal; superior parietal; fusiform precentral; and cerebellar (VIIII, IX, and Crus II) regions. Importantly, there is notable overlap between the affected regions and those responsible for both motoric and cognitive control of gait (7).

Table 5.

Baseline characteristics by CKD status in the magnetic resonance imaging sample

| No CKD, n=83 | CKD, n=32 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 75±5 | 77±7 |

| Women, n (%) | 38 (46) | 19 (59) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 61 (74) | 24 (75) |

| Black | 19 (23) | 8 (25) |

| Other | 3 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| High school or less | 13 (16) | 10 (31) |

| College | 35 (42) | 13 (41) |

| Postgraduate | 35 (42) | 9 (28) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, n=112 | 27.2 (24.4–33.7) | 27.0 (24.5–30.5) |

| Ever regular smoker, n (%), n=114 | 35 (43) | 19 (59) |

| Comorbidities, Global Health Score, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 15 (18) | 6 (19) |

| 1 | 28 (34) | 12 (38) |

| 2 | 25 (30) | 5 (16) |

| ≥3 | 15 (18) | 9 (28) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 20 (24) | 8 (25) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 53 (64) | 17 (53) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%), n=114 | 42 (51) | 17 (53) |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 5 (6) | 5 (17) |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n (%) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Head trauma, n (%), n=110 | 14 (18) | 6 (19) |

| Depression requiring treatment, n (%), n=114 | 9 (11) | 4 (13) |

| General mental status, RBANS total score, | 93.6±11.9 | 89.7±12.2 |

| Cognitive status, n (%) | ||

| Normal | 71 (86) | 27 (84) |

| MCI | 12 (15) | 5 (16) |

| BP systolic, n=112 | 134±18 | 130±20 |

| BP diastolic, n=112 | 80±9 | 80±15 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m 2 | 74±10 | 49±8 |

| ≥75, n (%) | 38 (46) | 0 |

| 60–<75, n (%) | 45 (54) | 0 |

| 45–<60, n (%) | 0 | 24 (75) |

| 30–<45, n (%) | 0 | 6 (19) |

| <30, n (%) | 0 | 2 (6) |

CKD defined as eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Continuous variables reported as mean±SD or median (interquartile range). RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Figure 3.

Gray matter covariance networks associated with CKD and gait phenotype. In red-yellow are negatively weighted regions: regions with relatively more atrophy in older adults with (A) CKD and (B) gait phenotype. In blue-green are positively weighted regions: regions with relatively less atrophy in older adults with (A) CKD and (B) gait phenotype. Threshold x/− z=1.96; P<0.05.

Gait Phenotype and Risk of Mild Cognitive Impairment

Finally, we sought to determine whether detection of the gait phenotype preceded clinically evident cognitive impairment; if so, it could potentially be useful for identifying high-risk individuals. After excluding participants with baseline mild cognitive impairment and those lacking follow-up cognitive assessments (Figure 1), over a median 3.1 years (IQR, 2.4–4.0), 29 participants received an incident clinical diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment syndrome (median time to diagnosis 1.2 years; IQR, 1.0–2.2 years). After multivariable adjustment including eGFR, the gait phenotype was associated with a nearly four-fold higher risk of mild cognitive impairment (hazard ratio, 3.91; 95% CI, 1.46 to 10.44). There was no evidence of effect modification by eGFR (P for interaction =0.80).

Discussion

Our findings in a cohort of community-dwelling older adults suggest that cognitive impairment and gait disturbances are interrelated phenomena in the context of CKD. Clinically detectable gait abnormalities modified the association of eGFR with cognitive function: lower eGFR was associated with poorer cognitive function only among adults who manifested the gait phenotype. Among participants with CKD, those with the gait phenotype had lower cognitive function; this was independent of risk factors for cognitive impairment, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Neuroimaging demonstrated that CKD was associated with gray matter atrophy in areas of the brain implicated in control of gait and cognition; the presence of the gait phenotype was associated with atrophy in these same regions. Finally, in at least some individuals, these gait abnormalities are clinically evident before the onset of mild cognitive impairment, suggesting that gait examination could provide clinically useful information for identifying older adults with CKD who are at high risk of cognitive decline.

These data are the first to link spatiotemporal gait abnormalities with poor cognitive function in nondialysis-dependent CKD. Importantly, these results were not generalizable to gait abnormalities in general, but were specific to the gait phenotype we have described. Although this phenotype is distinct from established neurologic gaits, it shares characteristics with the unsteady and frontal gait phenotypes described in the general elderly population (5). Both unsteady and frontal gaits are associated with greater risk for vascular dementia in older adults; vascular dementia is the most common subtype of dementia in patients with CKD (4,5). Like unsteady gait, this gait phenotype is associated with a higher risk of falls (14,41). Thus, the gait abnormalities we have described in adults with CKD appear to share common substrates with the pathologic processes mediating unsteady gait, frontal gait, and vascular dementia.

Our work builds on prior studies linking gait dysfunction with cognitive decline in the general elderly population: not only was the gait phenotype associated with poorer cognitive function in older adults with CKD, but it was this subset of individuals who demonstrated the most profound deficits in both gait performance (14) and cognitive testing. Thus, in this study population, joint gait and cognitive dysfunction was most prevalent among older adults who had experienced mild-to-moderate loss of eGFR. Furthermore, these gait abnormalities may be a precursor to mild cognitive impairment. The gait phenotype was associated with incident mild cognitive impairment, and a number of the cognitive domains most affected by the presence of CKD and the gait phenotype are those affected in pre-mild cognitive impairment, a period of accelerated cognitive decline before meeting criteria for mild cognitive impairment (42,43). This raises the intriguing possibility that the detection of specific spatiotemporal gait abnormalities may offer a tool for detecting a “pre-mild cognitive impairment” stage in patients with CKD.

The association of the gait phenotype with executive function is of particular interest. Executive function is the single domain most commonly associated with gait dysfunction (10). Impaired executive function is observed not only among older adults with CKD, but also among younger adults and children with CKD (44,45). Furthermore, executive function and gait appear to be mediated by similar areas in the brain (10), suggesting that common neural substrates may underlie their alteration in CKD.

Indeed, our imaging analyses show that the gait phenotype shares common neural substrates with CKD, and both are linked with cognition. A fairly widespread network of gray matter atrophy was associated with CKD, including cerebellar, occipital, temporal, parietal, precentral, and frontal regions. An even more widespread, yet topographically similar, pattern of gray matter atrophy was associated with the gait phenotype. This is consistent with previous observations of gray matter loss in frontal and temporal regions in individuals with CKD who exhibited impaired executive function (46). There is notable overlap between the affected areas and those associated with the motoric cognitive risk syndrome, including regions responsible for both motoric and cognitive control of gait (7). Prior studies have also reported alteration of brain structures linked to gait and cognition in patients with kidney disease, as well as vascular brain pathologies and reduced gray matter volume (47 –49). Although atrophy has been observed across many brain regions in CKD, deep brain structures and the prefrontal, frontal, and temporal cortex are the most frequently affected. As with impaired executive function, these changes have been observed in both pediatric and adult CKD populations (32 –35,47). Taken together, these analyses identified a pattern of gray matter atrophy common to both CKD and the gait phenotype, which involved brain regions linked with cognition.

Several limitations of our analyses should be noted. Cross-sectional associations with cognitive test performance do not demonstrate temporality, and a relatively small number of individuals developed mild cognitive impairment. However, the stringent definition of mild cognitive impairment on the basis of case-conference adjudication is a strength. Nevertheless, it will be important to validate these findings in other cohorts. CKD was defined on the basis of a single measure of serum creatinine because of a lack of additional blood or urine laboratory data; participants with albuminuria but preserved eGFR would have been misclassified as not having CKD. Relatively few participants in the MRI sample had an eGFR <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, likely limiting the pathology observed in association with CKD; conversely, these data indicate that the atrophy pattern associated with the gait phenotype is present even with mild reduction in eGFR. Finally, our findings emerge from a community-dwelling, older adult population, which may not be representative of all patients with CKD. It will be particularly important to determine if similar associations are observed in younger patients with CKD and in those with more advanced CKD.

In conclusion, our findings support a shared pathogenesis underlying CKD, gait dysfunction, and cognitive impairment, and suggest that gait examination could add clinically useful information to CKD care.

Disclosures

M.K. Abramowitz reports employment with Albert Einstein College of Medicine; consultancy agreements with Tricida, Inc.; ownership interest in Aethlon Medical, Inc.; and honoraria from the National Kidney Foundation. E.I. Ayers reports employment with Albert Einstein College of Medicine; consultancy agreements with Saint Care Corporation; and serving as an Associate Editor of the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. H.M. Blumen reports employment with Albert Einstein College of Medicine. M. J. Koren reports employment with New York Presbyterian - Weill Cornell Medical Center. J. Verghese reports employment with AECOM and serving as a scientific advisor for or member of Journal of American Geriatrics Society, Journal of Gerontology, Neurodegenerative Disease Management, CatchU, and MedRhythms Inc.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants K23DK099438 (to M.K. Abramowitz), R01AG036921 and R01AG044007 (to J. Verghese), and a Resnick Gerontology Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, intramural grant (to J. Verghese).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.16091020/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Cognitive testing scores by gait phenotype and CKD status.

Supplemental Table 2. MNI coordinates of key brain regions (peak voxels in clusters) contributing to the gray matter volume covariance network associated with CKD.

Supplemental Table 3. MNI coordinates of key brain regions (peak voxels in clusters) contributing to the gray matter volume covariance network associated with the gait phenotype.

Supplemental Appendix 1. MRI preprocessing pipeline and multivariate analyses.

References

- 1. Weiner DE, Seliger SL: Cognitive and physical function in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 23: 291–297, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tuokko H, Frerichs R, Graham J, Rockwood K, Kristjansson B, Fisk J, Bergman H, Kozma A, McDowell I: Five-year follow-up of cognitive impairment with no dementia. Arch Neurol 60: 577–582, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Perna L, Wahl HW, Mons U, Saum KU, Holleczek B, Brenner H: Cognitive impairment, all-cause and cause-specific mortality among non-demented older adults. Age Ageing 44: 445–451, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zammit AR, Katz MJ, Bitzer M, Lipton RB: Cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults with chronic kidney disease: A review. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 30: 357–366, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verghese J, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Kuslansky G, Katz MJ, Buschke H: Abnormality of gait as a predictor of non-Alzheimer’s dementia. N Engl J Med 347: 1761–1768, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ambrose AF, Noone ML, Pradeep VG, Johnson B, Salam KA, Verghese J: Gait and cognition in older adults: Insights from the Bronx and Kerala. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 13[Suppl 2]: S99–S103, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blumen HM, Allali G, Beauchet O, Lipton RB, Verghese J: A gray matter volume covariance network associated with the motoric cognitive risk syndrome: A multicohort MRI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 74: 884–889, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Otobe Y, Hiraki K, Hotta C, Nishizawa H, Izawa KP, Taki Y, Imai N, Sakurada T, Shibagaki Y: Mild cognitive impairment in older adults with pre-dialysis patients with chronic kidney disease: Prevalence and association with physical function. Nephrology (Carlton) 24: 50–55, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morris R, Lord S, Bunce J, Burn D, Rochester L: Gait and cognition: Mapping the global and discrete relationships in ageing and neurodegenerative disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 64: 326–345, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen JA, Verghese J, Zwerling JL: Cognition and gait in older people. Maturitas 93: 73–77, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berger I, Wu S, Masson P, Kelly PJ, Duthie FA, Whiteley W, Parker D, Gillespie D, Webster AC: Cognition in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 14: 206, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Torres RV, Elias MF, Seliger S, Davey A, Robbins MA: Risk for cognitive impairment across 22 measures of cognitive ability in early-stage chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 299–306, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Savica R, Wennberg AM, Hagen C, Edwards K, Roberts RO, Hollman JH, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Machulda MM, Petersen RC, Mielke MM: Comparison of gait parameters for predicting cognitive decline: The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. J Alzheimers Dis 55: 559–567, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tran J, Ayers E, Verghese J, Abramowitz MK: Gait abnormalities and the risk of falls in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 983–993, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, Coats MA, Muich SJ, Grant E, Miller JP, Storandt M, Morris JC: The AD8: A brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology 65: 559–564, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holtzer R, Mahoney JR, Izzetoglu M, Wang C, England S, Verghese J: Online fronto-cortical control of simple and attention-demanding locomotion in humans. Neuroimage 112: 152–159, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Kuslansky G, Sliwinski MJ, Stewart WF, Verghese J, Crystal HA, Buschke H: Screening for dementia by telephone using the memory impairment screen. J Am Geriatr Soc 51: 1382–1390, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO: Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 17: 37–49, 1982-1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF III, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration): A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med 155: 408, 2011]. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group: KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. 2013. Available at: https://kdigo.org/guidelines/ckd-evaluation-and-management. Accessed February 25, 2021

- 21. Verghese J, Katz MJ, Derby CA, Kuslansky G, Hall CB, Lipton RB: Reliability and validity of a telephone-based mobility assessment questionnaire. Age Ageing 33: 628–632, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyere O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Visser M, Zamboni M; Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2: Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis [published correction appears in Age Ageing 48: 601, 2019 10.1093/ageing/afz046]. Age Ageing 48: 16–31, 2019. 30312372 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN: The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): Preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 20: 310–319, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buschke H: Selective reminding for analysis of memory and learning. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav 12: 543–550, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Monsch AU, Bondi MW, Butters N, Salmon DP, Katzman R, Thal LJ: Comparisons of verbal fluency tasks in the detection of dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol 49: 1253–1258, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reitan RM: The relation of the Trail Making Test to organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol 19: 393–394, 1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised (WAIS-R), New York, Psychological Corporation, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goodglass H, Kaplan E, Weintraub S: Boston Naming Test (Experimental Edition), Boston, Boston University, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 29. American Psychiatric Association: DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Allali G, Annweiler C, Blumen HM, Callisaya ML, De Cock AM, Kressig RW, Srikanth V, Steinmetz JP, Verghese J, Beauchet O: Gait phenotype from mild cognitive impairment to moderate dementia: Results from the GOOD initiative. Eur J Neurol 23: 527–541, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, Bäckman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC: Mild cognitive impairment--Beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med 256: 240–246, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burnham KP, Anderson DR: Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach, New York, Springer, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Efron B, Tibshirani R: An Introduction to the Bootstrap, New York, Chapman & Hall, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blumen HM, Brown LL, Habeck C, Allali G, Ayers E, Beauchet O, Callisaya M, Lipton RB, Mathuranath PS, Phan TG, Pradeep Kumar VG, Srikanth V, Verghese J: Gray matter volume covariance patterns associated with gait speed in older adults: A multi-cohort MRI study. Brain Imaging Behav 13: 446–460, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brickman AM, Habeck C, Zarahn E, Flynn J, Stern Y: Structural MRI covariance patterns associated with normal aging and neuropsychological functioning. Neurobiol Aging 28: 284–295, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Habeck C, Krakauer JW, Ghez C, Sackeim HA, Eidelberg D, Stern Y, Moeller JR: A new approach to spatial covariance modeling of functional brain imaging data: Ordinal trend analysis. Neural Comput 17: 1602–1645, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Habeck C, Stern Y; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: Multivariate data analysis for neuroimaging data: Overview and application to Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Biochem Biophys 58: 53–67, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Steffener J, Brickman AM, Habeck CG, Salthouse TA, Stern Y: Cerebral blood flow and gray matter volume covariance patterns of cognition in aging. Hum Brain Mapp 34: 3267–3279, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abadie A, Imbens GW: Bias-corrected matching estimators for average treatment effects. J Bus Econ Stat 29: 1–11, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wright IC, McGuire PK, Poline JB, Travere JM, Murray RM, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS, Friston KJ: A voxel-based method for the statistical analysis of gray and white matter density applied to schizophrenia. Neuroimage 2: 244–252, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Verghese J, Ambrose AF, Lipton RB, Wang C: Neurological gait abnormalities and risk of falls in older adults. J Neurol 257: 392–398, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Howieson DB, Carlson NE, Moore MM, Wasserman D, Abendroth CD, Payne-Murphy J, Kaye JA: Trajectory of mild cognitive impairment onset. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 14: 192–198, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seo EH, Kim H, Lee KH, Choo IH: Altered executive function in pre-mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 54: 933–940, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mendley SR, Matheson MB, Shinnar S, Lande MB, Gerson AC, Butler RW, Warady BA, Furth SL, Hooper SR: Duration of chronic kidney disease reduces attention and executive function in pediatric patients. Kidney Int 87: 800–806, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hailpern SM, Melamed ML, Cohen HW, Hostetter TH: Moderate chronic kidney disease and cognitive function in adults 20 to 59 years of age: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2205–2213, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tsuruya K, Yoshida H, Haruyama N, Fujisaki K, Hirakata H, Kitazono T: Clinical significance of fronto-temporal gray matter atrophy in executive dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease: The VCOHP study. PLoS One 10: e0143706, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Moodalbail DG, Reiser KA, Detre JA, Schultz RT, Herrington JD, Davatzikos C, Doshi JJ, Erus G, Liu HS, Radcliffe J, Furth SL, Hooper SR: Systematic review of structural and functional neuroimaging findings in children and adults with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1429–1448, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Qiu Y, Lv X, Su H, Jiang G, Li C, Tian J: Structural and functional brain alterations in end stage renal disease patients on routine hemodialysis: A voxel-based morphometry and resting state functional connectivity study. PLoS One 9: e98346, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang LJ, Wen J, Ni L, Zhong J, Liang X, Zheng G, Lu GM: Predominant gray matter volume loss in patients with end-stage renal disease: A voxel-based morphometry study. Metab Brain Dis 28: 647–654, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.