Significance Statement

Older patients with advanced CKD are at high risk for serious complications and death. Although advance care planning (ACP) is critical to patient-centered care, why such patients seldom discuss ACP with their kidney clinicians is incompletely understood. Data from interviews with 68 patients, care partners, and clinicians in the United States demonstrate they held discordant views about who is responsible for raising ACP and the scope of ACP. Many nephrologists did not view ACP as their responsibility, leaving ACP insufficiently discussed in nephrology clinics, shifting responsibility to patients and primary care providers, and often leading patients to address ACP concerns outside of the medical sphere, if at all. Training nephrologists and clarifying their role in ACP are critical to increasing equitable access to ACP for older patients with CKD.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, patient centered, advance care planning, advance directives, qualitative, disparities, chronic kidney failure, ethnic minority, quality of life

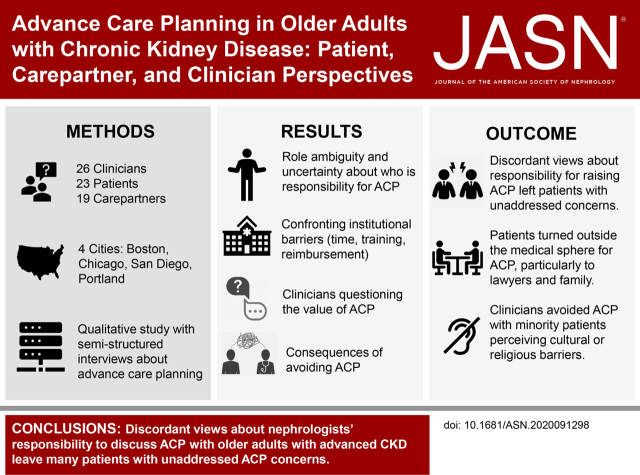

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Older patients with advanced CKD are at high risk for serious complications and death, yet few discuss advance care planning (ACP) with their kidney clinicians. Examining barriers and facilitators to ACP among such patients might help identify patient-centered opportunities for improvement.

Methods

In semistructured interviews in March through August 2019 with purposively sampled patients (aged ≥70 years, CKD stages 4–5, nondialysis), care partners, and clinicians at clinics in across the United States, participants described discussions, factors contributing to ACP completion or avoidance, and perceived value of ACP. We used thematic analysis to analyze data.

Results

We conducted 68 semistructured interviews with 23 patients, 19 care partners, and 26 clinicians. Only seven of 26 (27%) clinicians routinely discussed ACP. About half of the patients had documented ACP, mostly outside the health care system. We found divergent ACP definitions and perspectives; kidney clinicians largely defined ACP as completion of formal documentation, whereas patients viewed it more holistically, wanting discussions about goals, prognosis, and disease trajectory. Clinicians avoided ACP with patients from minority groups, perceiving cultural or religious barriers. Four themes and subthemes informing variation in decisions to discuss ACP and approaches emerged: (1) role ambiguity and responsibility for ACP, (2) questioning the value of ACP, (3) confronting institutional barriers (time, training, reimbursement, and the electronic medical record, EMR), and (4) consequences of avoiding ACP (disparities in ACP access and overconfidence that patients’ wishes are known).

Conclusions

Patients, care partners, and clinicians hold discordant views about the responsibility for discussing ACP and the scope for it. This presents critical barriers to the process, leaving ACP insufficiently discussed with older adults with advanced CKD.

Early advance care planning (ACP) can align patient preferences for care before the need for urgent decision making and can improve shared decision making—a process where patients, care partners, and clinicians discuss evidence-based options, balancing patient values and goals.1,2 For older patients facing dialysis decisions, early ACP is especially important, because for many, dialysis may offer marginal survival benefit and has significant quality-of-life implications, including for end-of-life care.3 Adjusted mortality among dialysis patients aged ≥75 is four-fold higher than age-matched nondialysis Medicare beneficiaries.4,5 Moreover, compared with patients with similarly complex chronic conditions, such as cancer, patients receiving dialysis are more than twice as likely to die in the intensive care unit, commonly countering patient preferences to die at home.6,7

Among older patients receiving maintenance dialysis, ACP is lower than in similar seriously ill populations despite potential benefits, and data are limited for patients with CKD stage 4–5.8,9 This may contribute to patients overestimating the dialysis benefit, not realizing dialysis initiation is a choice, regretting dialysis, and receiving end-of-life care discordant with their wishes.10–15 Notably, patients were less likely to regret dialysis if they had discussed prognosis or had completed ACP documentation.16 Although many want information about their prognosis and treatment options, nephrologists infrequently discuss prognosis and conservative care, and focus most on dialysis initiation.17–21

This study aims to better understand ACP preferences and expectations among patients, care partners, and clinicians to improve ACP outcomes and delivery, including where patients turn when ACP needs are not met by clinicians. Building on prior studies that were largely limited to single centers, specific populations (e.g., veterans, patients on dialysis), or a single perspective (e.g., patients), this multisite qualitative study examined a geographically diverse sample of patients, care partners, and clinicians concurrently, focusing on variation in ACP experiences, barriers to ACP, and opportunities for improving patient-centered care among older adults facing dialysis decisions.

Methods

Setting, Participants, and Study Design

Semistructured interviews were conducted as part of the multisite, mixed-methods Decision Aid for Renal Therapy (DART) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03522740). In 2018–2019, the DART Trial recruited 400 English-fluent patients aged >70 years with nondialysis CKD and eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 receiving care at nephrology clinics in Greater Boston, Portland (Maine), San Diego, and Chicago. A subset of participants was recruited for this qualitative study on the basis of purposive sampling criteria: sex, age, region, and education (patients), and years in practice (clinicians). Participants were identified using electronic health record queries; nephrologists confirmed eligibility and recruited via letters. Care partners (dyads), identified by patients as people (nonclinicians) with whom they discuss health care decisions, were approached and consented independently. Clinicians were identified from departmental rosters and recruited via email. Tufts Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Interview Guide and Data Collection

On the basis of literature review and clinical experiences, a social scientist with expertise in qualitative methods and kidney disease (K.L.) developed the semistructured interview guide. The guide was refined through deliberation with the research team (authors) and the DART Stakeholder Advisory Board, which ensured interpretability. Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers (K.L., N.D., and I.N.) from March through August 2019 by telephone, after giving informed verbal consent. Open-ended questions examined patients’, caregivers’, and clinicians’ preferences and approaches to ACP, barriers, and facilitators to completing ACP, and documentation. ACP was defined as a “type of decision that people sometimes have to make related to the kind of medical care they want in case of life-limiting illness or injury. Part of ACP may be documenting your wishes should there come a time when you cannot speak for yourself.”

Analysis

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews continued until thematic saturation and sufficient variation in sampling criteria were achieved and confirmed through deliberation at weekly meetings.22 Following a thematic analytic approach, K.L. developed the preliminary codebook, following the interview guide.23 Subsequently, at least two researchers (K.L., N.D., and I.N.) independently coded 15 interviews line by line, allowing new codes to emerge inductively.24 K.L., N.D., and I.N. revised the codebook and independently recoded the initial interviews and ten additional purposively selected transcripts. Iterative deliberation between the qualitative team (K.L., N.D., and I.N.) yielded consensus about coding discrepancies, emergent codes, and amended coding descriptions. N.D., and I.N. applied the final codebook to the remaining transcripts. In a second stage, using NVivo (version 11; QSR Int), codes were organized into categories through a consensus process using pattern and focused coding to capture the range and variability of subthemes and to characterize both confirmatory and contradictory narratives.23 Preliminary themes were discussed by the research team (all authors) and advisory board. K.L., N.D., and I.N. then iteratively compared and clarified themes, K.L. reconciled any discrepancies, and produced a final set of themes. Study reporting reflects Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research.25

Results

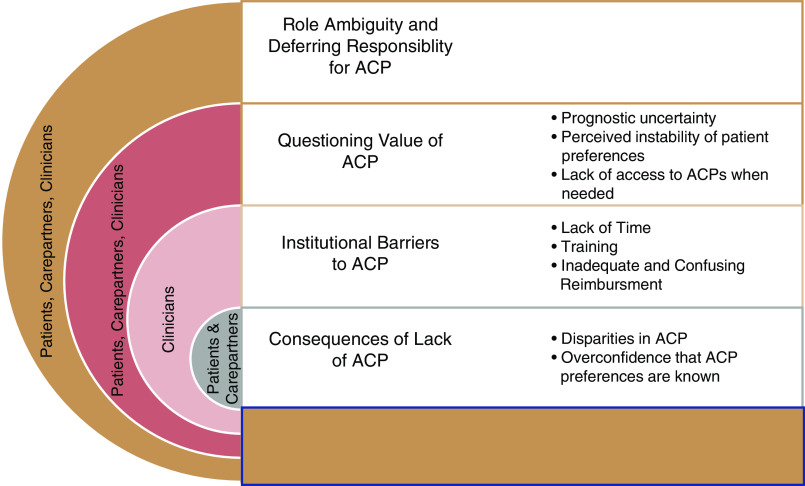

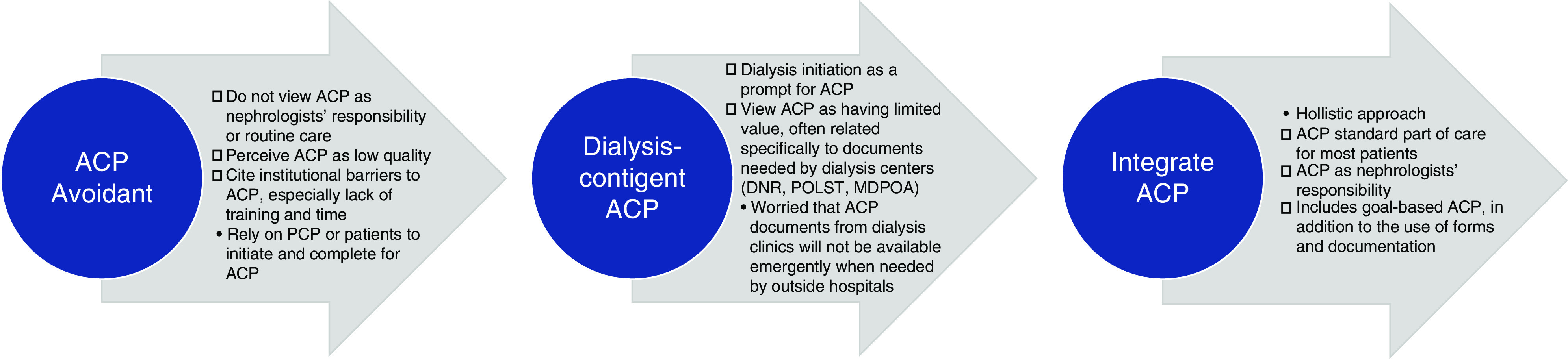

We conducted 68 semistructured interviews (26 clinicians; 23 patients; 19 care partners), with balanced participation across sites; 85% of clinicians were nephrologists and 87% of patients had care partners (dyads) (Table 1). Most clinicians were from academic medical centers. In total, 52% of patients had completed ACP documents, mostly outside of the health care setting, and 27% of clinicians regularly discussed ACP with patients. Four themes clarified variation in ACP experiences among patients, care partners, and clinicians1: role ambiguity and responsibility for ACP2; questioning the value of ACP3; confronting institutional barriers (time, training, reimbursement); and consequences of avoiding ACP (disparities in access to ACP, overconfidence that patients’ wishes are known)4 (Figure 1). Facilitators and barriers to completing ACP spanning these themes were also identified. Figure 2 illustrates the continuum of ACP approaches, from avoiding ACP to fully adopting ACP.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Clinician (n=26) | Patient (n=23) | Care Partner (n=19) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count (%) | |||

| ACP status a | |||

| Completed | 12 (52) | ||

| Not completed | 7 (32) | ||

| Unknown | 4 (14) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 14 (54) | 11 (48) | 7 (37) |

| Female | 12 (46) | 12 (52) | 12 (63) |

| Age | |||

| 40–49 | N/A | 2 (11) | |

| 50–59 | N/A | 1 (5) | |

| 60–69 | N/A | 8 (42) | |

| 70–79 | 17 (74) | 7 (37) | |

| 80–89 | 5 (22) | 1 (5) | |

| 90+ | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Clinician type | |||

| Nephrologist | 22 (85) | ||

| Physician assistant | 4 (15) | ||

| Yr in practice | |||

| 0–5 | 1 (4) | ||

| 6–10 | 7 (27) | ||

| >10 | 17 (65) | ||

| Region | |||

| Boston | 8 (31) | 7 (30) | 5 (26) |

| Chicago | 6 (23) | 7 (30) | 6 (32) |

| San Diego | 7 (27) | 7 (30) | 6 (32) |

| Portland, Maine | 5 (19) | 2 (10) | 2 (10) |

| Dialysis status | |||

| Yes | 2 (9) | N/A | |

| No | 21 (91) | N/A | |

| Race | |||

| White | 15 (65) | 15 (79) | |

| Black | 7 (30) | 3 (16) | |

| Other | 1 (4) | 1 (5) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 (9) | 2 (11) | |

| Education level | |||

| High school or less | 4 (17) | 1 (5) | |

| Some college or technical school | 7 (30) | 9 (47) | |

| College graduate | 6 (26) | 4 (21) | |

| Postgraduate | 6 (26) | 5 (26) | |

| Care partner status | |||

| Has a care partner | 20 (87) | N/A | |

ACP was considered completed when discussions resulted in formal documentation (e.g., physician orders for life-sustaining treatment or equivalent, medical power of attorney).

Figure 1.

Themes and subthemes reflecting barriers to advance care planning for older patients with advanced CKD in nephrology clinics: patient, carepartner, and clinician perspectives.

Figure 2.

Differences in clinician approaches to ACP: perspectives on role ambiguity and responsibility for ACP. DNR, do not resuscitate; POLST, physician orders for life-sustaining treatment; MDPOA, medical durable power of attorney.

Role Ambiguity and Responsibility for ACP

Participants disagreed about who should initiate ACP conversations and what role patients, care partners, and clinicians have, with each group perceiving the other as better equipped to raise ACP.

Most patients and care partners wanted holistic conversations about ACP, including disease trajectory, prognosis, and goals of care. Some patients felt responsible but unable to raise ACP with clinicians, alluding to a power differential. “Unless I press [the clinician], he doesn’t think that going into these details about the future and future choices I’ve got to make is timely” (Patient 41). Another described feeling at fault for not raising ACP, “I like the doctor I got. He doesn’t tell me too much [about ACP] and I don’t ask him too much, so it’s probably my fault too” (Patient 28). Role ambiguity and limited knowledge stymied patients’ ability to raise ACP: “Whatever [the clinician] tells us, we go along with. I don’t think that we’re knowledgeable enough to ask the right questions [about ACP]” (Care partner 51). Another elaborated “[I] need to have an advocate, champion in the medical field” (Patient 27). Care partners generally perceived their role as formal healthcare proxy or informal support system, but not as responsible for raising ACP. One explained, “[ACP is] usually [a patient’s] decision, and I just try to support” (Care partner 61). Lack of ACP discussions in clinical settings led patients elsewhere. Many patients turned to lawyers to complete medical durable power of attorney, living will, and do-not-resuscitate documentation. One patient said, “We have our living will… and everything done… just with my attorney” (Patient 48).

Across all sites, few clinicians routinely discussed ACP with patients. Most clinicians did not view ACP as their responsibility, discussing ACP only if asked directly or after patients initiated dialysis. “My efforts focus primarily around dialysis decision making but not broader goals” (Clinician 25). Another clarified: “I don’t ask about [ACP]. If they start dialysis, our social workers at the dialysis units do that” (Clinician 20). Another noted, “I don’t do [ACP] with my clinic patients. I figure, we’ll deal with the dialysis, which is difficult enough” (Clinician 4). Many felt ACP was not routine nephrology practice.

Unlike patients, who described ACP as a broader goal of care discussions, most clinicians defined ACP more narrowly, focusing on completion of documentation. One said, “Other than talking about dialysis, I never [discuss] intubation, resuscitation, CPR… I don’t ask them about [power of attorney], I don’t ask them for advance directives or anything” (Clinician 8). Some were less likely to discuss ACP with older patients. “If I have a 95-year-old patient with CKD stage 4, we may not talk about [end-of-life] planning, because I think they won the game of life already. We just want them to transition to the other side as smoothly as possible” (Clinician 21). Reliance on primary care for ACP was common. “I don’t consider [ACP] to be within my province as a nephrologist. I think that’s a discussion they should be having with their primary care provider (PCP)” (Clinician 8). Another said, “We do count on the primary care to get [ACP] in order” (Clinician 19).

A quarter of clinicians routinely conducted ACP and viewed it as their responsibility. “[ACP]… is definitely a nephrologist’s role” (Clinician 11). These clinicians viewed themselves as the patient’s principal clinician. “I don’t think [patients] can make informed decisions about their care without having [ACP] as part of it” (Clinician 1). They defined ACP more globally, “to get at what the patient wants out of the last years of their life… [what] their aspirations are” (Clinician 9). Instead of deferring to PCPs, these nephrologists partnered with PCPs to improve care continuity. “I think, maybe even more importantly, it’s helpful for the patient to have heard the same message [about ACP] from several different doctors from different specialties” (Clinician 11).

Questioning the Value of ACP

Clinicians perceived ACP’s value as increasing their confidence and knowledge of patient wishes. “It benefits the patient to have clearly elucidated their wishes to several doctors” (Clinician 11). Another noted that ACP discussions “giv[e] patients time to figure out what they want” (Clinician 9). However, for many clinicians, prognostic uncertainty, perceived instability of patient preferences, and limited access to ACP documents when needed outweighed ACP’s value. One explained, “[ACP] is often of much less value than people imagine, because so often people come back... they say, ‘Oh no, I wouldn’t want any of that done, unless of course there was a chance that I could recover’” (Clinician 17). Another stated, “I try not to have discussions on prognosis. If somebody asks how long they’re going to live if they choose not to do dialysis, I tell them I don’t know” (Clinician 10). Clinicians often described conversations as focused on treatment decisions as opposed to conversations about values and quality of life. Clinicians were uncertain whether patient wishes documented in ACP would match their wishes at time of deteriorating health status. “Some [patients say] ‘No, I never want to do dialysis,’ but when they’re sick they may change their mind because they’re feeling it or the family forces them” (Clinician 24) and “Deteriorating health… makes people change their decisions” (Clinician 3).

ACP was viewed as low value because clinicians noted ACP documents were inaccessible in emergencies or to outside hospitals. “If they’re at a local hospital… where they’re not on the same EMR system, [accessing ACPs is] probably going to [be]… tough” (Clinician 12). Absence of a clear location in the EMR discouraged clinicians from formal documentation. “We don’t do the [ACP] documents or anything like that” (Clinician 24). “It’s mostly informal, I still don’t have documents for them. I don’t ask to see [ACP documents] if [patients] have them” (Clinician 5). Some clinicians resorted to detailing patient preferences in their notes, understanding that few clinicians would look there.

Patients valued ACP as it provided emotional relief and ability to plan. “I wanted to make sure that everybody was on the same page because if I get too sick, I’ll be too tired” (Patient 40). Another explained that ACP helped them explore vital questions, such as “What your lifestyle is, whether or not you want to continue it, and how you can continue it. Will you have enough money [and]… support systems…?” (Care partner 50). Contrasting with clinician perspectives, most patients saw prognostic information as integral to ACP’s value. “I’ve certainly asked ‘How much time do I have before I'm going to be going into kidney failure?’ I’ve gotten some general feedback … but… [not] the specificity that I want” (Patient 27). Meanwhile, some patients believed their disease progression did not necessitate ACP conversations. “Since my GFR and creatinine have held fairly level for the last year or so, there hasn’t been any need for [ACP discussion]” (Patient 43). A care partner opined, “I’d like to know how urgent [the ACP discussion] is at this point. [Decline] doesn’t seem imminent” (Care partner 61).

Institutional Barriers to ACP: Time, Training, Reimbursement

Clinicians noted lack of time and training and poor reimbursement as barriers to ACP. One explained, “As physicians we’re constantly being tasked with everything… in 20 minutes. An hour of time is needed for [ACP] conversations” (Clinician 15). Lack of training led many clinicians to feel unprepared. One said, “[We] are not trained to do it so well, and yet [we] have a very sick population that needs [us] to be their advocates” (Clinician 9). Reimbursement for ACP was an additional barrier. Few knew how to use the ACP billing codes issued by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). “I know [the ACP billing code] is out there, [but] I don’t know how to use it” (Clinician 1). Confusion over how to separate ACP from CKD care led to idiosyncratic use of ACP codes. “I’m aware of [ACP codes], although not of what the bill is or how to bill for it” (Clinician 11).

Consequences of Avoiding ACP

Disparities and Avoiding ACP with Patients in Minority Groups

Some clinicians were uncomfortable discussing ACP with patients from minority or underserved backgrounds, viewing them as less willing to discuss ACP. “I think it’s uncomfortable to talk about these types of things for certain folks. I find that more in non-White backgrounds” (Clinician 25). Another explained they did not discuss ACP because patients from minority backgrounds held “suspicion about the medical system and why we’re doing things and how we're doing things” (Clinician 11). Another noted that, “[for Asian patients] talking about death is sort of taboo, so it’s sometimes difficult to get all the family members on board. [They] don’t always necessarily agree and implement that plan” (Clinician 14).

Clinicians noted language and cultural barriers contributed to difficult or uncomfortable ACP conversations, especially with underserved populations. Some clinicians were self-reflective about this challenge: “I think that I’m not as good speaking to people who have a different background than me, and I noticed that” (Clinician 20). Many cited the difficulty of having sensitive conversations through interpreters. One explained, “Language is a big [barrier]… One of the things that can really help is if there’s an English-speaking family member” (Clinician 13). Another described, “I have a Filipino gentleman who… I don’t feel is a very good candidate for dialysis... I always used the Tagalog interpreter…. [but] I do struggle that I’m not communicating [dialysis futility] well to them” (Clinician 25). Another said, “Some interpreters, they don’t just interpret what you say or what the patient says... I know they weren’t saying everything I was saying” (Clinician 21).

Clinicians were also concerned about upsetting or being blamed by patients. “It doesn’t matter how many times you say one thing, [patients] don’t hear it… Those are often the patients that have complaints about [clinicians] doing something wrong” (Clinician 1). Reflecting on barriers to ACP, he acknowledged, “There are some patients that either I don’t communicate well with, or they … just hav[e] trouble hearing me… communication is broken down, and so it makes it very hard to have a tough conversation about life expectancy” (Clinician 1).

Overconfidence that Clinicians Know Patients’ ACP Wishes

Despite never communicating directly about ACP, most patients felt their wishes were known and would be respected. One stated, “[Clinicians] never asked about [ACP], but they know my preference” (Patient 43). For patients and clinicians alike, confidence was grounded in close patient-clinician relationships and belief that clinicians could extrapolate information about patient personality, lifestyle, and values to preferences in ACP. “[The clinician] knows I’m active… and we did have that one brief conversation the last time I saw her about transplant. So, she must be aware [of my ACP preferences]” (Patient 41). Clinicians emphasized rapport and longstanding relationships with patients. “If I don’t know what’s going on and I don’t know [the patient] well, then they don’t trust me to really make [ACP] decisions” (Clinician 13). Patients expressed similarly unspoken trust in care partners, “We implicitly know that we can trust each other if we couldn’t make the decision ourselves” (Patient 27). Clinicians noted that initiating ACP discussions was easier when patients were already well informed about ACP. “It’s helpful if someone has already asked [about ACP] because… a lot of people just have just never thought about it” (Clinician 15).

Discussion

Despite high risks of hospitalization, intensive care, and death among older patients with kidney failure, few discuss ACP with their kidney clinicians. Consistent with prior studies, we found that nephrologists insufficiently engage in timely, deliberative ACP,26 and are reluctant to discuss prognosis with patients with advanced CKD.27–29 Triangulating data from a national sample of patients, care partners, and clinicians, we found that discordant views about responsibility for raising ACP and its scope were critical barriers to ACP, leaving patients reliant on resources outside the health care system to plan for inevitable health declines. Some nephrologists were challenged by engaging people of color and non-native English speakers, further exacerbating disparities. Clinicians, patients, and care partners viewed strong personal relationships and trust as foundational to ACP, and this also contributed to overconfidence that ACP preferences were known, even when not discussed. Our study identified key barriers to ACP in nephrology and highlighted opportunities for improving patient-centered care.

Many clinicians did not view ACP within their scope of responsibilities, deferring ACP to PCPs and patients, whereas patients felt burdened with raising the topic, perceiving an authority differential and not understanding whether ACP was needed. Consequently, many patients turned to nonmedical support for ACP, potentially leaving medical needs unaddressed. Yet, nephrologists who perceived themselves as the patient’s principal clinician routinely engaging in ACP and viewed ACP as integral to quality care. Many deemed ACP to be a low-value activity: a time-intensive, poorly reimbursed, potentially upsetting conversation with a low likelihood that documents will be found when needed. Although nephrologists focused on treatment decision making, they often missed opportunities to more deeply assess patient values and goals of care. Instead of merely focusing on discrete decisions about treatment initiation, nephrologists can approach ACP as a broader conversation about whether treatments are likely to advance patients’ life goals and quality of life, and which treatments are best able to support patient goals.

Actionable approaches to improve ACP include clarifying ACP as a core component of nephrologists’ roles, consistent with the goals of the Advancing Kidney Health Initiative. Integrating established ACP programs (e.g., Serious Illness Conversation Project) during fellowship and continuing medical education may establish ACP as a core competency for kidney clinicians. Importantly, newer models of care, such as the Kidney Care Choices program, have emphasized patient activation and the role of kidney clinicians as “principal providers” for older patients with advanced CKD, encouraging greater participation in ACP.30–33 Clearer institutional protocols and greater reimbursement for ACP may help.34 In 2016, the CMS began offering reimbursement to clinicians for ACP discussions, although early data show minimal use by nephrologists.35 Additionally, EMR documentation and interoperability across providers remain significant barriers. Greater sharing of ACP, such as new state laws in Colorado to share ACP documents across all hospitals, is critical. More immediately, clarity on where documents are stored, and standard forms may improve ACP.

Although challenging, ACP conversations can improve end-of-life outcomes and reduce emotional distress.17 Discussion of prognosis is associated with more realistic patient expectations and has not been shown to harm patients’ emotional wellbeing or patient-physician relationships.36 For care partners, ACP discussions can reduce decision-making burden.37 When clinicians facilitate ACP, both care partners and clinicians felt more confident identifying treatment consistent with patients’ preferences.28,38 This reinforces the need for iterative discussions before decision making becomes urgent. ACP is most effective when clinicians introduce the topic and promote shared decision making, leading to greater patient and family satisfaction, congruence, and reduced decisional conflict.1,37,39 New interactive, web-based decision aids, such as DART, which is geared toward older patients facing dialysis decisions, can help guide kidney clinicians and empower patients to discuss their treatment and ACP preferences.

Clinicians highlighted the difficulty of approaching ACP with persons of color and those needing interpreters, populations often with lower health literacy.40,41 These findings help explain persistent underutilization of palliative care and greater dialysis discontinuation and nonhospital or hospice death among non-White patients on dialysis.42,43 Disparities may be further exacerbated by the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected older minorities with CKD. To mitigate disparities, the kidney community must increase clinical efforts to provide culturally sensitive care to underserved groups, potentially partnering with trusted community partners, such as faith organizations, community health clinics, and local business leaders.

Study strengths include a deeper understanding of ACP perceptions, barriers, and facilitators experienced by older patients facing dialysis decisions, care partners, and clinicians in four geographically diverse regions of the United States, including rural and urban areas. Study limitations include the underrepresentation of Hispanic patients and lack of data about clinician race. Recall bias is also a limitation, somewhat mitigated by interviewing patients and care partners proximal to clinical encounters. Additionally, we did not include non-English speaking patients in this study, a population that may be particularly underserved. Although patients perceive that clinicians understand their wishes, this perception often is unsupported by ACP discussions or documentation. Patients, care partners, and clinicians each perceived the other as more responsible. Clarifying nephrologists’ roles in culturally sensitive ACP, investing in EMR coordination, and reducing disincentives may improve patient-centered care for older people with CKD.

Disclosures

D. Rifkin reports being a scientific advisor or member of the American Journal of Kidney Diseases (AJKD) Editorial Board (feature editor), American Board of Internal Medicine Nephrology Exam Committee member; and having other interests/relationships as co-investigator of US sites, and the EMPA-KIDNEY study (pending). D. Weiner reports receiving consulting honoraria from Akebia Therapeutics, Cara Therapeutics, Janssen Biopharmaceuticals, and Tricida; and reports the following compensation paid to his institution: AstraZeneca (site Principal Investigator [PI], capitated on the basis of recruitment, completed 2020); Dialysis Clinic, Inc. (including local site PI for multiple clinical trials contracted through Dialysis Clinic Inc. including trials sponsored by Ardelyx, ongoing, and Cara Therapeutics, completed); Goldfinch Bio (site PI, capitated on the basis of recruitment, ongoing); Janssen Biopharmaceuticals (site PI, capitated on the basis of recruitment, completed 2019); reports receiving honoraria from the National Kidney Foundation for an editorial position at Kidney Medicine and AJKD, Elsevier, for royalties from the Primer on Kidney Diseases; reports being a scientific advisor or member as Co-Editor-in-Chief of National Kidney Foundation Primer on Kidney Diseases eighth edition, Editor-in-Chief of Kidney Medicine, Dialysis Clinic Inc. Medical Director Research Committee, member of ASN Quality and Policy Committees, ASN representative to Kidney Care Partners, Scientific Advisory Board of National Kidney Foundation; and other interests/relationships as Chair of adjudications committee of VALOR Trial (George Institute). E. Gordon reports receiving honoraria and travel reimbursements for presentations and meetings, United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Ethics Committee, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Data and Safety Monitoring Board (NIAID DSMB), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) DSMB, National Institutes of Health ad hoc study section grant reviewer; reports being a scientific advisor or member of Associate Editor for Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics, Associate Editor for American Journal of Transplantation, and member of Advisory Committee on Blood and Tissue Safety and Availability, NHLBI DSMB, NIAID DSMB, and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Committee; reports having other interests/relationships as member of the American Society of Transplantation (AST) Living Donor Community of Practice, Ex officio Chair of Ethics Committee for United Network for Organ Sharing, Co-Chair of AST Psychosocial and Ethics Community of Practice, and Member of AST IDEAL Task Force. J. Wong reports other interests/relationships as a member of the US Preventive Services Task Force, Associate Statistical Editor of Annals of Internal Medicine, Publications Committee member of Massachusetts Medical Society, panel member of American Association for the Study of Liver Disease and Infectious Diseases Society of America, Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C, and Chief Scientific Officer for Tufts Medical Center. K. Ladin reports other interests/relationships as Chair of UNOS Ethics Committee, Steering Committee for National Kidney Foundation Patient Network, and NHLBI DSMB. T. Isakova received consulting honorariums from Akebia Therapeutics, Inc., Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd., LifeSci Capital, LLC; and is an Associate Editor for AJKD. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (CDR-2017C1-6297).

Acknowledgments

The views presented in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the PCORI, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

N. D’Arcangelo, K. Ladin, and I. Neckerman drafted the manuscript; K. Ladin designed and oversaw the study; K. Ladin and D. Weiner obtained funding for the research; and all authors contributed to data access and collection, analysis, development of conclusions, and reviewed and contributed significantly to the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial “Advance Care Planning in Kidney Disease: A Tale of Two Conversations,” on pages 1273–1274.

References

- 1. Briggs LA, Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Song M-K, Colvin ER: Patient-centered advance care planning in special patient populations: A pilot study. J Prof Nurs 20: 47–58, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, Hanson LC, Meier DE, Pantilat SZ, et al.: Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 53: 821–832. e1, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verberne WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ: Comparative survival among older adults with advanced kidney disease managed conservatively versus with dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 633–640, 2016. 10.2215/CJN.07510715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wachterman MW, O’Hare AM, Rahman OK, Lorenz KA, Marcantonio ER, Alicante GK, et al.: One-year mortality after dialysis initiation among older adults. JAMA Intern Med 179: 987–990, 2019. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LYC, Bragg-Gresham J, Balkrishnan R, et al.: US renal data system 2018 annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 73[Suppl 1]: A7–A8, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663; discussion 663–664, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wachterman MW, Lipsitz SR, Lorenz KA, Marcantonio ER, Li Z, Keating NL: End-of-life experience of older adults dying of end-stage renal disease: A comparison with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 54: 789–797, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reich AJ, Jin G, Gupta A, Kim D, Lipstiz S, Prigerson HG, et al.: Utilization of ACP CPT codes among high-need Medicare beneficiaries in 2017: A brief report. PLoS One 15: e0228553, 2020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0228553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurella Tamura M, Liu S, Montez-Rath ME, O’Hare AM, Hall YN, Lorenz KA: Persistent gaps in use of advance directives among nursing home residents receiving maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med 177: 1204–1205, 2017. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ladin K, Lin N, Hahn E, Zhang G, Koch-Weser S, Weiner DE: Engagement in decision-making and patient satisfaction: A qualitative study of older patients’ perceptions of dialysis initiation and modality decisions. Nephrol Dial Transplant 32: 1394–1401, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ladin K, Buttafarro K, Hahn E, Koch-Weser S, Weiner DE: “End-of-life care? I’m not going to worry about that yet.” health literacy gaps and end-of-life planning among elderly dialysis patients. Gerontologist 58: 290–299, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, Cohen RA, Waikar SS, Phillips RS, et al.: Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1206–1214, 2013. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baddour NA, Siew ED, Robinson-Cohen C, Salat H, Mason OJ, Stewart TG, et al.: Serious illness treatment preferences for older adults with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 2252–2261, 2019. 10.1681/ASN.2019040385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saeed F, Sardar MA, Davison SN, Murad H, Duberstein PR, Quill TE: Patients’ perspectives on dialysis decision-making and end-of-life care. Clin Nephrol 91: 294–300, 2019. 10.5414/CN109608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goff SL, Eneanya ND, Feinberg R, Germain MJ, Marr L, Berzoff J, et al.: Advance care planning: A qualitative study of dialysis patients and families. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 390–400, 2015. 10.2215/CJN.07490714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saeed F, Ladwig SA, Epstein RM, Monk RD, Duberstein PR: Dialysis regret: Prevalence and correlates. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 957–963, 2020. 10.2215/CJN.13781119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davison SN, Simpson C: Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: Qualitative interview study. BMJ 333: 886, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilman EA, Feely MA, Hildebrandt D, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, Chong EY, Williams AW, et al.: Do patients receiving hemodialysis regret starting dialysis? A survey of affected patients. Clin Nephrol 87: 117–123, 2017. 10.5414/CN109030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA: Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: A qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 495–503, 2012. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wong SPY, McFarland LV, Liu CF, Laundry RJ, Hebert PL, O’Hare AM: Care practices for patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med 179: 305–313, 2019. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parvez S, Abdel-Kader K, Pankratz VS, Song MK, Unruh M: Provider knowledge, attitudes, and practices surrounding conservative management for patients with advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 812–820, 2016. 10.2215/CJN.07180715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patton M: Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, Beverly Hills, CA, Sage, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chase S, Narrative Inquiry: Multiple Lenses, Approaches and Voices, Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Saldana J: The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J: Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19: 349–357, 2007. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oskoui T, Pandya R, Weiner DE, Wong JB, Koch-Weser S, Ladin K: Advance care planning among older adults with advanced non-dialysis-dependent CKD and their care partners: Perceptions versus reality? Kidney Med 2: 116–124, 2020. 10.1016/j.xkme.2019.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Couchoud C, Hemmelgarn B, Kotanko P, Germain MJ, Moranne O, Davison SN: Supportive care: Time to change our prognostic tools and their use in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1892–1901, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holley JL: Advance care planning in CKD/ESRD: An evolving process. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1033–1038, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. O’Hare AM, Szarka J, McFarland LV, Taylor JS, Sudore RL, Trivedi R, et al.: Provider perspectives on advance care planning for patients with kidney disease: Whose job is it anyway? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 855–866, 2016. 10.2215/CJN.11351015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nair D, Cavanaugh KL: Measuring patient Activation as part of kidney disease policy: Are we there yet? J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 1435–1443, 2020. 10.1681/ASN.2019121331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mendu ML, Weiner DE: Health policy and kidney care in the United States: Core curriculum 2020. Am J Kidney Dis 76: 720–730, 2020. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eneanya ND, Labbe AK, Stallings TL, Percy S, Temel JS, Klaiman TA, et al.: Caring for older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease and considering their needs: A qualitative study. BMC Nephrol 21: 213, 2020. 10.1186/s12882-020-01870-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. University of Michigan Kidney Epidemiology and Cost Center: End-stage renal disease physician level measures technical expert panel summary report., Available at: https://www.dialysisdata.org/sites/default/files/content/ESRD_Measures/Physician_Level_Measure_TEP_Summary_Report_09062018.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2020

- 34. Ladin K, Smith AK: Active medical management for patients with advanced kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med 179: 313–315, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Belanger E, Loomer L, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Adhikari D, Gozalo PL: Early utilization patterns of the new Medicare procedure codes for advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med 179: 829–830, 2019. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Enzinger AC, Zhang B, Schrag D, Prigerson HG: Outcomes of prognostic disclosure: Associations with prognostic understanding, distress, and relationship with physician among patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 33: 3809–3816, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W: The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 340: c1345, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wendler D, Rid A: Systematic review: The effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med 154: 336–346, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Song M-K, Ward SE, Fine JP, Hanson LC, Lin F-C, Hladik GA, et al.: Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: A randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 813–822, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eneanya ND, Olaniran K, Xu D, Waite K, Crittenden S, Hazar DB, et al.: Health literacy mediates racial disparities in cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge among chronic kidney disease patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved 29: 1069–1082, 2018. 10.1353/hpu.2018.0080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Eneanya ND, Wenger JB, Waite K, Crittenden S, Hazar DB, Volandes A, et al.: Racial disparities in end-of-life communication and preferences among chronic kidney disease patients. Am J Nephrol 44: 46–53, 2016. 10.1159/000447097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Foley RN, Sexton DJ, Drawz P, Ishani A, Reule S: Race, ethnicity, and end-of-life care in dialysis patients in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2387–2399, 2018. 10.1681/ASN.2017121297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wen Y, Jiang C, Koncicki HM, Horowitz CR, Cooper RS, Saha A, et al.: Trends and racial disparities of palliative care use among hospitalized patients with ESKD on dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1687–1696, 2019. 10.1681/ASN.2018121256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]