Significance Statement

The effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on adult and pediatric nephrology fellows’ education, preparedness for unsupervised practice, and emotional wellbeing are unknown. The authors surveyed 1005 nephrology fellows-in-training and recent graduates in the United States and 425 responded (response rate 42%). Nephrology training programs rapidly adopted telehealth and virtual learning to meet pandemic-mandated safety measures. Despite these changes, 84% of respondents indicated programs successfully sustained their education and helped them progress to unsupervised practice and board certification. Although 42% of respondents perceived that the pandemic negatively affected their overall quality of life and 33% reported a poorer work-life balance, only 15% met the Resident Well-Being Index distress threshold. As the pandemic continues, nephrology training programs must continue to provide a safe educational environment and monitor fellows’ wellbeing.

Keywords: nephrology training, COVID-19 pandemic, physician burnout, COVID-19

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic’s effects on nephrology fellows’ educational experiences, preparedness for practice, and emotional wellbeing are unknown.

Methods

We recruited current adult and pediatric fellows and 2020 graduates of nephrology training programs in the United States to participate in a survey measuring COVID-19’s effects on their training experiences and wellbeing.

Results

Of 1005 nephrology fellows-in-training and recent graduates, 425 participated (response rate 42%). Telehealth was widely adopted (90% for some or all outpatient nephrology consults), as was remote learning (76% of conferences were exclusively online). Most respondents (64%) did not have in-person consults on COVID-19 inpatients; these patients were managed by telehealth visits (27%), by in-person visits with the attending faculty without fellows (29%), or by another approach (9%). A majority of fellows (84%) and graduates (82%) said their training programs successfully sustained their education during the pandemic, and most fellows (86%) and graduates (90%) perceived themselves as prepared for unsupervised practice. Although 42% indicated the pandemic had negatively affected their overall quality of life and 33% reported a poorer work-life balance, only 15% of 412 respondents who completed the Resident Well-Being Index met its distress threshold. Risk for distress was increased among respondents who perceived the pandemic had impaired their knowledge base (odds ratio [OR], 3.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.00 to 4.77) or negatively affected their quality of life (OR, 3.47; 95% CI, 2.29 to 5.46) or work-life balance (OR, 3.16; 95% CI, 2.18 to 4.71).

Conclusions

Despite major shifts in education modalities and patient care protocols precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, participants perceived their education and preparation for practice to be minimally affected.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is challenging every aspect of kidney care, research, and education.1 Nephrologists have faced higher rates of AKI,2 challenges in dialysis delivery,3,4 and increased mortality in patients with concomitant COVID-19 and kidney dysfunction.5–8 Health care workers overall have faced increased anxiety and depression during this pandemic.9,10 Caring for complex patients with COVID-19 and kidney dysfunction likely worsens provider stress and increases risk for mental health diagnoses. Additionally, the pandemic has brought about major changes in the delivery of nephrology care, including the adoption of preparedness checklists,11 increased use of telemedicine,12,13 and an emphasis on critical care nephrology.14 Nephrology will learn from these lessons in attempts to deliver improved care in the future, with or without a pandemic.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has likely created lasting changes in nephrology care delivery, it has also created educational challenges and opportunities to meet these clinical demands. Before the pandemic, nephrology faced low recruitment,15 adverse perceptions of the field,16–18 and significant trainee burnout.19 Whether the pandemic has changed these perceptions is unclear.

In a national survey, we explored the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on nephrology fellows’ educational experiences, preparedness for practice, and personal wellbeing.

Methods

The American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Data Subcommittee (the manuscript’s coauthors; chaired by the senior author) developed a research survey instrument to assess the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the education and wellbeing of current fellows and recent graduates who completed training during the initial US COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020.

Since 2014, the ASN has conducted an annual survey of current nephrology fellows to capture the demographics of the incoming workforce, fellows’ perceptions of their training and the specialty, and leading indicators of the status of the local and national nephrology job market.20 Although the 2020 survey (to be distributed in May) was canceled, as the pandemic accelerated there was a need for information on how the pandemic was affecting fellows-in-training. A customized survey—that included select questions from the annual instrument for longitudinal data collection—was distributed in August 2020 to measure COVID-19’s effect on fellows’ education, professional development, career trajectory, and personal life. Psychologic distress was evaluated using the Resident Well-Being Index (RWBI), which “…correlates with quality of life (QOL), fatigue, recent suicidal ideation, burnout, the likelihood of reporting a recent major medical error, and meaning in work.”21 The RWBI’s distress threshold (RWBI score ≥5; score range 0–7) is associated with a three-fold higher risk of poor mental QOL and a four-fold higher risk of burnout, a “psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job.”22 A known occupational hazard among health care providers, burnout comprises “exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.” The final survey instrument, including the RWBI, was validated and distributed via Qualtrics (see Supplemental Material I).

The survey frame was drawn from three sources. Participant rosters for ASN’s In-Training Examination (an annual board certification preparatory test administered each spring) were reviewed to identify current (academic year 2020–2021) second- and third-year adult nephrology fellows and recent (2020) graduates. Contacts for pediatric and adult/pediatric fellows were provided by the American Society of Pediatric Nephrology. Lastly, first-year fellows (who began nephrology training in July 2020) were retrieved from the ASN’s membership database and provided by training programs. Respondents’ demographic characteristics, including education status (international medical graduate [IMG] versus US medical graduate [USMG] versus US citizen graduate of an international medical school [US IMG]), were compared with the most-recent data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) for representativeness.

Email invitations with unique survey links were distributed on August 4, 2020. The target audience was incentivized to participate by an opportunity to win one of 12 prizes (two complimentary registrations to ASN’s Board Review Course and Update and 10 1-year ASN memberships). Dissemination was timed to: (1) mitigate recall bias of fellows’ experiences during the initial surges in March and April 2020; (2) occur after the start of the academic year and completion of the new-fellow onboarding process (which started July 1, 2020); and (3) conclude before the typical onset of influenza season (the survey closed after 41 days on September 14, 2020). To evaluate how surges in patients with COVID-19 may have affected response, participants were geolocated and aggregated by the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) week of their survey completion date. Then, participants were mapped against the corresponding mean patient with COVID-19 hospitalizations aggregated by state for each MMWR week the survey was open.

Participants’ educational, professional, and personal experiences during the COVID-19 era were evaluated for any intercohort differences between fellows and recent graduates (using chi-squared test for independence or Fisher’s exact test). It was hypothesized that any observed differences could be a potential surrogate indicator of changing educational and practice approaches during the pandemic’s course. Potential associations between fellow and graduate demographic variables and aspects of personal wellbeing (the exposures) and occupational distress (the outcome, measured using the RWBI) were evaluated by univariable (both exposures) and multivariable (demographic variables) analyses using logistic regression.

The pandemic has increased demands on many physicians’ time. We considered this when designing our instrument. Our priority was to query broadly about a range of topics rather than pursue granularity on a few. Therefore, most questions were either developed or reframed as closed end. Although the number of open-ended questions were purposely underweighted in an attempt to reduce participant burden, participants had the option to provide free-text responses via an “Other (please specify)” option in 17% of questions (12 out of 69 total). (Note that, on the basis of their responses and question relevance, participants were not exposed to every question.) This limited the volume of free-text responses, which were manually reviewed and collated for representative data only. No formal qualitative analysis was performed.

Where appropriate, summary statistics are reported as median (interquartile range; IQR) or mean±SD. Logistic regression results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Statistical tests (chi-squared test for independence, Fisher’s exact test, or logistic regression) were conducted at α=0.01. The research was reviewed and deemed exempt by Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board (IRB00205206) with the caveat that respondents could skip questions they preferred not to answer. Thus, percentages reported were calculated using question-specific total responses in the denominator. Statistical analysis was conducted using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/).23–25

Results

The survey audience comprised 1005 nephrology fellows-in-training and recent graduates, 110 specializing in pediatric nephrology and 895 in adult. In total, 436 participated and 11 were censored for nonresponse, yielding 425 responses (response rate 42.3%). Overall, 68% (n=291) were current adult, pediatric, or adult/pediatric fellows (first years, n=56; second years, n=193; and third years or beyond, n=42), and 32% (n=134) recent graduates (98.5% in adult and 1.5% in adult/pediatric nephrology).

Respondent demographics (Table 1) were representative of adult and pediatric trainee populations per ACGME data.26 Overall, participants were geographically representative of the US population by Census division. However, there are disproportionally more fellowship programs (35% of total) located in the Middle-Atlantic and New England divisions, leading to overrepresentation of these regions (24% and 9%, respectively). Participants were located in multiple states with high COVID-19 hospitalizations (mean 608–1075 hospitalized-patients/state per MMWR week during the survey period) (Figure 1, Supplemental Material II: Supplemental Figure 1).27,28

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating nephrology fellows and recent graduates

| Characteristic | Current Fellows (n=291) a | Graduates (n=134) a |

|---|---|---|

| Fellowship, n (%) | ||

| Adult nephrology | 230 (79) | 132 (99) |

| Pediatric nephrology | 57 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Adult/pediatric nephrology | 4 (1.4) | 2 (1.5) |

| Educational status, n (%) | ||

| USMG | 143 (49) | 61 (46) |

| IMG | 130 (45) | 65 (49) |

| US IMG | 18 (6) | 8 (6) |

| Median age in yr (IQR) | 32 (4) | 33 (3) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 124 (43) | 51 (38) |

| Black | 16 (6) | 6 (5) |

| South Asian | 80 (28) | 40 (30) |

| East Asian | 30 (10) | 6 (5) |

| Southeast Asian | 14 (5) | 11 (8) |

| Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Multiple | 6 (2) | 4 (3) |

| Other | 17 (6) | 14 (11) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic | 30 (10) | 18 (13) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 146 (50) | 87 (65) |

| Female | 145 (50) | 46 (34) |

| Prefer not to answer | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Citizenship status, n (%) | ||

| Native-born US citizen | 129 (44) | 55 (41) |

| Naturalized US citizen | 42 (14) | 27 (20) |

| Permanent resident | 30 (10) | 15 (11) |

| H-1, H-2, or H-3 visa (temporary worker) | 23 (7.9) | 17 (13) |

| J-1 or J-2 visa (exchange visitor) | 64 (22) | 19 (14) |

| Other visa | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Median educational debt in US$1000s (IQR) | 161 (257) | 213 (298) |

Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

Figure 1.

Respondent locations (circles) overlaid on a map showing cumulative patients with COVID-19 as of the survey open date (August 4, 2020). COVID-19 data from COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University.

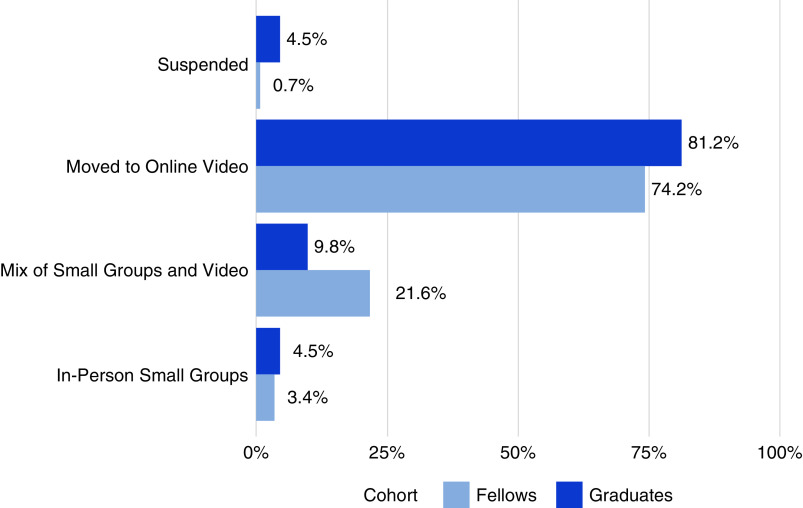

We first looked at COVID-19’s effect on educational conferences and patient rounding. The pandemic precipitated a massive shift in nephrology education. Before COVID-19, half of respondents had “never” or “rarely” used remote learning, but by the initial outbreak most conferences were entirely online (76% overall; fellows 74%; graduates 81%). Since the pandemic’s start, educational settings have evolved, with 22% of current fellows’ conferences a mix of online and small in-person groups (P<0.01, Fisher’s exact test) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Changes to nephrology conference settings for nephrology fellows and recent graduates during the COVID-19 era—ASN COVID-19 Fellow Survey.

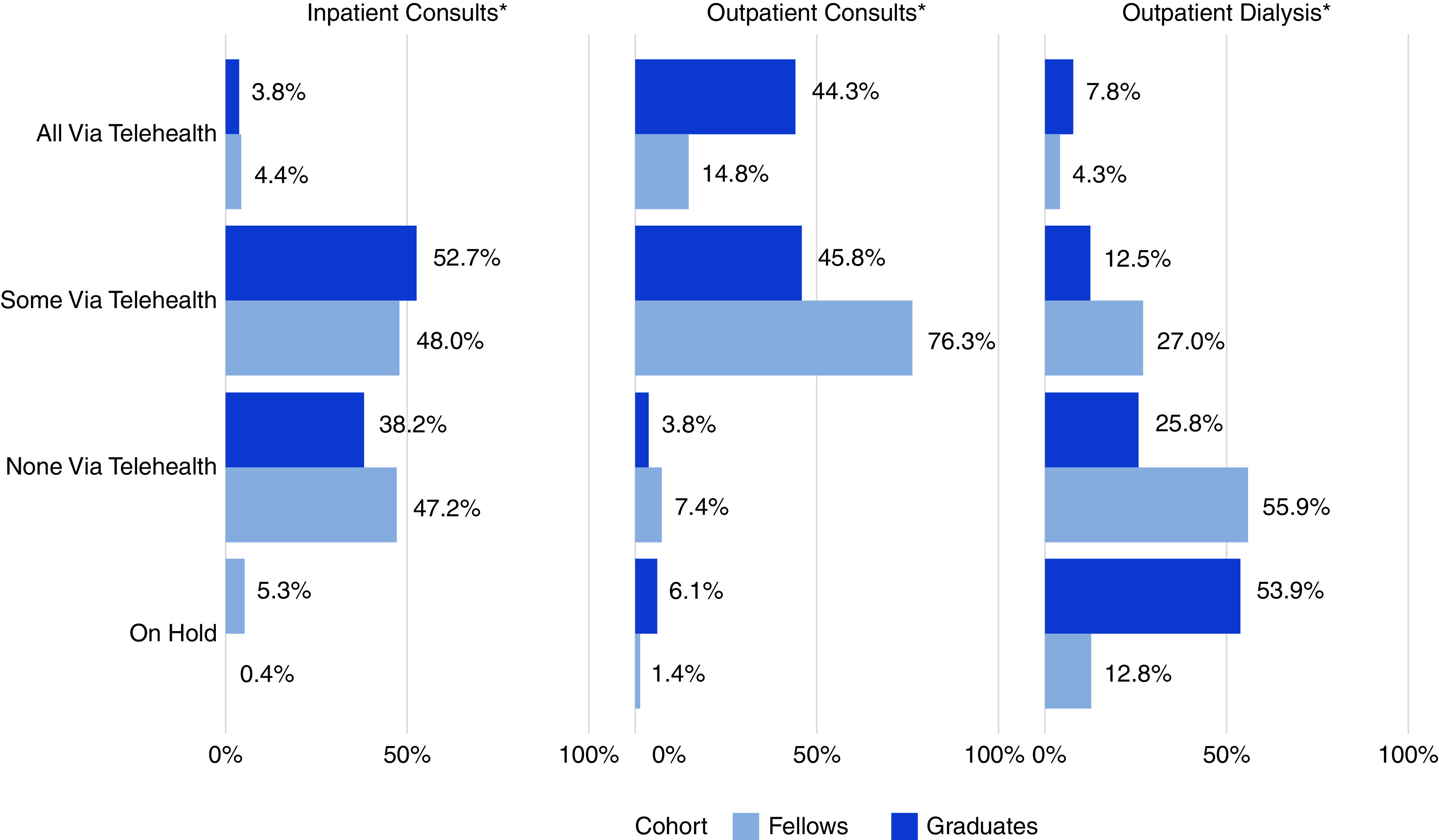

Beginning March 6, 2020, telehealth access expanded under an 1135 Waiver that reimbursed telemedicine at the same rate as in-person patient visits.29 Telehealth was adopted in a majority of nephrology consults for inpatients (52% of fellows and 56% of graduates seeing “some” or “all” patients via telehealth) and outpatients (91% and 90%, respectively) (Figure 3). Differing proportions of fellows and graduates using telehealth for “some” and “all” consults was observed; 44% of recent graduates managed all outpatients via telehealth compared with 15% of current fellows (P<0.01, Fisher’s exact test). Half of the 2020 graduates were withdrawn from outpatient dialysis services versus 13% of current fellows. Respondents observed the increase in telehealth volume had reduced the outpatient missed-appointment rate.

Figure 3.

Telehealth utilization by patient care setting for nephrology fellows and recent graduates in the COVID-19 era—ASN COVID-19 Fellow Survey. *Fisher's exact test, P<0.01.

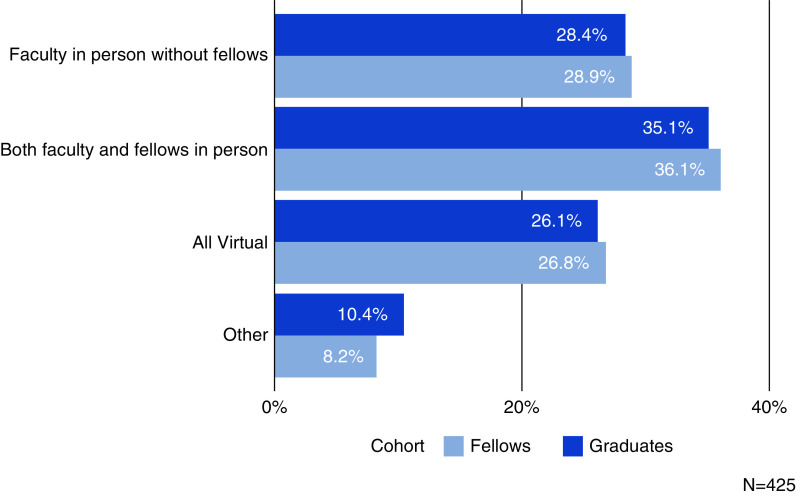

Most participants (64%) did not consult on COVID-19 inpatients in person. Rather, these patients were managed entirely by telehealth (27%), by attending faculty in person without fellows (29%), or with another approach (9%). Only 36% said both attending faculty and fellows comanaged patients with COVID-19 in person (Figure 4) (see Supplemental Material III: Supplemental Tables 1–4 geographic variation in rounding and management of patients with COVID-19). Adoption of management approaches for patients with COVID-19 were similar between recent graduates and current fellows. “At the very beginning, I saw all patients with COVID and refused to allow my attendings to accompany me [because I felt I was safer] as I was younger and double exposure was stupid,” one fellow said. “Now the process is mostly one exam early in the admission, with mostly virtual care afterwards with further exams only when clinically relevant.” Respondents said the preferred management strategy for patients with COVID-19 was telemedicine in concert with the primary care team’s assessment, unless an in-person dialysis-access or patient-volume evaluation was required.

Figure 4.

Management approaches used for inpatients who were COVID-19 positive—ASN COVID-19 Fellow Survey.

Beyond telemedicine, fellows reported implementing iPad rounding, team collaboration on Doximity, and visual patient inspection behind glass or using intensive care unit (ICU) video feeds when consulting on patients with COVID-19 in isolation. Emergent peritoneal dialysis for patients with COVID-19 in the ICU and with kidney failure was among the dialysis modalities respondents used to manage the early 2020 surge in the volume of patients with COVID-19. Other modalities included sustained low-efficiency dialysis, prolonged intermittent RRT, shared continuous RRT (1 day on and 1 day off), and in-room dialysis. In total, 47 fellows (11%) were redeployed, mainly to either the general medicine inpatient service or ICU.

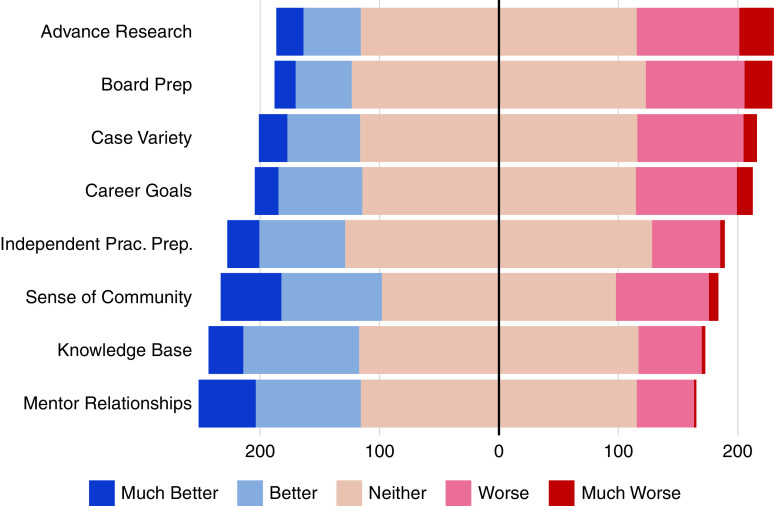

Despite the many pandemic-influenced modifications in educational modalities and patient care approaches that trainees experienced, most indicated the changes had minimal effects on their professional development. Although a quarter of respondents perceived their case variety and clinical experiences (24%), preparation for board certification (25%), and ability to complete research (28%) had been impaired by the pandemic, fewer said their knowledge base (13% indicating “worse” or “much worse” since the start of the pandemic) or readiness for unsupervised practice (15%) had been negatively affected. Whereas 24% overall said their career goals and trajectory were adversely affected by the pandemic, less than one fifth of those preparing to enter practice (second-year adult or third-year pediatric fellows) reported their job search was complicated regarding geographic location (17%) or practice setting (14%). In total, 18% said COVID-19 worsened their ultimate job selection process, and 37% of graduates had difficulty finding a nephrology position they were satisfied with, most of whom were IMGs (72%). Yet, one third of respondents felt their mentor relationships and sense of community within their training program had improved (“better” or “much better”) since the COVID-19 pandemic began (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on facets of professional development—ASN COVID-19 Fellow Survey. Prac., practice; Prep, preparation.

Regarding perceptions of professional development, most fellows (84%) and graduates (82%) “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that their fellowship programs were successful in sustaining their education during the pandemic (mean 4.2±0.9; median 4; IQR, 1; scale of 1–5 where 1 is “strongly disagree” and 5 is “strongly agree”). Most respondents—86% of fellows and 90% of graduates—perceived themselves as prepared for independent practice on conclusion of their fellowship4. Most fellows and graduates (87%) would recommend nephrology to medical students and residents, up 9% from the 2019 ASN fellow survey.20

Of the 412 who completed the RWBI, 15% met the distress threshold (RWBI score ≥5)—16% of current fellows (n=46) and 12% of graduates (n=15) (chi-squared test for independence, P=0.28). The proportion of respondents meeting the RWBI distress threshold (15%) and mean RWBI score observed (2.04±2.03) was lower than the original RWBI validation cohort of 1700 residents and fellows (20% and 2.64±1.98, respectively).21 Median RWBI scores (overall median RWBI score 2; IQR, 3) were similar between adult (2; IQR, 3.25) and pediatric (2; IQR, 4) fellows, but slightly higher for women (2; IQR, 4 versus 1; IQR, 3 for men) and USMGs (2; IQR 4, versus 1; IQR, 3 for IMGs). Univariable and multivariable analyses found no significant associations between any demographic variables and an RWBI score meeting the distress threshold (P≥0.06) (Table 2), which could be due to substantial class imbalances in some subgroups. However, there was an increased risk for the distress threshold outcome (RWBI ≥5) in respondents who perceived the pandemic had impaired their knowledge base (OR, 3.04; 95% CI, 2.00 to 4.77), board certification preparation (OR, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.54 to 3.12), or career trajectory (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.42 to 2.93) (all univariable logistic regression). Those perceiving their program had not sustained their education were also at increased distress risk (OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 1.53 to 2.72) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Association of distress (RWBI score ≥5) with demographic characteristics of nephrology fellows and recent graduates

| Demographic Characteristic | Univariable a | Multivariable a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Sex | 412 | ||||||

| Male | — | — | — | — | |||

| Female | 1.48 | 0.86 to 2.56 | 0.16 | 1.76 | 0.95 to 3.28 | 0.072 | |

| Race | 407 | ||||||

| White | — | — | — | — | |||

| Black | 1.47 | 0.40 to 4.39 | 0.52 | 1.79 | 0.46 to 5.74 | 0.35 | |

| East Asian | 0.42 | 0.06 to 1.51 | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.06 to 1.49 | 0.22 | |

| Multiple | 0.69 | 0.04 to 3.95 | 0.73 | 0.51 | 0.03 to 3.33 | 0.55 | |

| Other | 1.30 | 0.41 to 3.51 | 0.62 | 1.20 | 0.31 to 3.90 | 0.77 | |

| Pacific Islander | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.00 | >0.99 | |||

| South Asian | 1.38 | 0.72 to 2.62 | 0.32 | 1.68 | 0.80 to 3.55 | 0.17 | |

| Southeast Asian | 0.89 | 0.20 to 2.85 | 0.86 | 1.14 | 0.24 to 4.16 | 0.85 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 411 | ||||||

| No | — | — | — | — | |||

| Yes | 1.98 | 0.91 to 4.05 | 0.071 | 2.50 | 0.95 to 6.27 | 0.054 | |

| Educational status | 412 | ||||||

| USMG | — | — | — | — | |||

| IMG | 0.94 | 0.53 to 1.65 | 0.83 | 0.64 | 0.33 to 1.23 | 0.18 | |

| US IMG | 1.02 | 0.28 to 2.89 | 0.98 | 0.44 | 0.09 to 1.50 | 0.23 | |

| Fellowship | 412 | ||||||

| Adult | — | — | — | — | |||

| Adult/Pediatric | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 0.99 | |||

| Pediatric | 0.78 | 0.31 to 1.72 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.17 to 1.45 | 0.23 | |

| Training yr | 412 | ||||||

| 1st | — | — | — | — | |||

| 2nd | 1.48 | 0.65 to 3.83 | 0.38 | 1.21 | 0.50 to 3.30 | 0.69 | |

| 3rd | 1.14 | 0.34 to 3.73 | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.23 to 3.58 | 0.91 | |

| Graduate | 0.90 | 0.36 to 2.49 | 0.83 | 0.66 | 0.23 to 1.95 | 0.43 | |

N, number of complete responses; —, reference level.

Logistic regression.

Table 3.

Association of worsening perceptions of professional and personal factors with distress (RWBI score ≥5) among nephrology fellows and recent graduates

| Factor | N | OR a | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nephrology education | ||||

| Knowledge base | 411 | 3.04 | 2.00 to 4.77 | <0.001 b |

| Board certification preparation | 410 | 2.17 | 1.54 to 3.12 | <0.001 b |

| Variety/breadth of clinical experiences | 411 | 1.11 | 0.80 to 1.55 | 0.54 |

| Ability to complete/advance research | 411 | 1.23 | 0.91 to 1.68 | 0.18 |

| Program successfully sustaining education during pandemic | 392 | 2.03 | 1.53 to 2.72 | <0.001 b |

| Career preparation | ||||

| Focusing career trajectory | 411 | 2.02 | 1.42 to 2.93 | <0.001 b |

| Job search location | 356 | 1.56 | 1.07 to 2.28 | 0.020 |

| Job search setting | 355 | 1.37 | 0.91 to 2.07 | 0.13 |

| First postfellowship job selection | 129 | 1.89 | 0.98 to 3.67 | 0.057 |

| Preparedness for unsupervised practice | 412 | 1.68 | 1.15 to 2.51 | 0.010 |

| Professional relationships | ||||

| Sense of community within training program | 409 | 1.22 | 0.91 to 1.64 | 0.19 |

| Relationships with mentors | 409 | 1.09 | 0.79 to 1.52 | 0.60 |

| Personal life experiences | ||||

| Relationships with family | 411 | 2.34 | 1.64 to 3.42 | <0.001 b |

| Relationships with friends | 412 | 1.97 | 1.39 to 2.87 | <0.001 b |

| Work-life balance | 412 | 3.16 | 2.18 to 4.71 | <0.001 b |

| Overall quality of life | 412 | 3.47 | 2.29 to 5.46 | <0.001 b |

N, number of complete responses.

Logistic regression.

P<0.01.

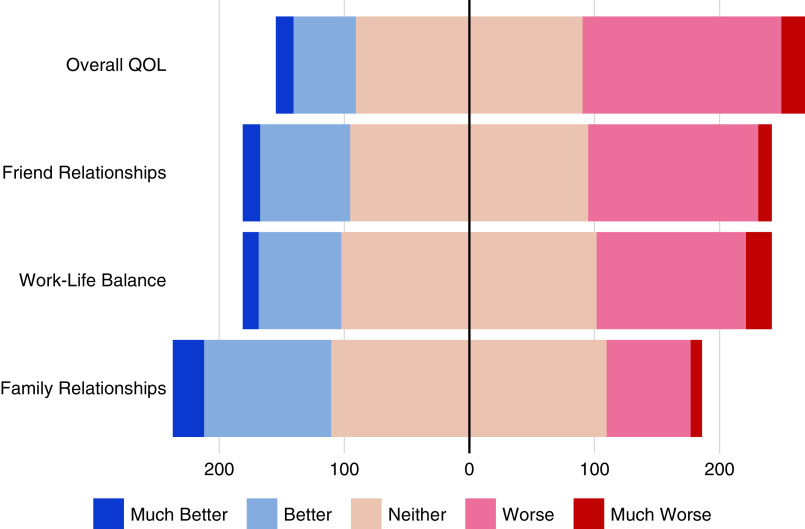

In contrast to the occupationally focused RWBI assessment, a higher percentage of respondents reported that training in the COVID-19 era took a toll on their personal lives. One third (33.1%) said their work-life balance and 42% their overall QOL was negatively affected (“worse” or “much worse” since the pandemic began; scale of 1–5 where 1 is “much better” and 5 is “much worse”) (Figure 6). This may have been exacerbated for the 13% of respondents reporting living with an individual at high risk for COVID-19 morbidity or mortality. On univariate analysis, all personal life factors examined were associated with an outcome of higher risk for distress. These adverse relationships included an increasingly poorer QOL or work-life balance associated with a three-fold higher risk of meeting the distress threshold outcome (RWBI ≥5) (OR, 3.47; 95% CI, 2.29 to 5.46, and OR, 3.16; 95% CI, 2.18 to 4.71, respectively). Worsening family relationships (OR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.64 to 3.42) and friend connections (OR 1.97; 95% CI, 1.39 to 2.87) were also associated with an increased risk for a distress outcome.

Figure 6.

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on facets of trainees’ and graduates’ personal life—ASN COVID-19 Fellow Survey.

Discussion

Our nationally representative study of current (2020–2021) nephrology fellows and recent (2020) graduates’ training during the COVID-19 pandemic found a rapid uptake of telehealth and virtual learning on the pandemic’s onset. Two thirds of inpatient-assigned nephrology fellows did not perform in-person consults on patients with COVID-19. Despite these potentially disruptive changes, most respondents said their fellowship program was successful in continuing their education and most perceived themselves as prepared for independent practice upon completion of fellowship. The pandemic complicated respondents’ career trajectories, with 29% of graduates changing their plans due to limited employment opportunities, 37% having difficulty in finding a satisfactory position, and 18% noting COVID-19 complicated their ultimate job-selection process. A total of 15% of respondents met the distress threshold (associated with a four-fold greater burnout risk). Those who perceived the pandemic had made it difficult to maintain their knowledge base or had contributed to a poorer overall QOL, worsened work-life balance, or deteriorated personal relationships with friends and family were at higher risk for having an RWBI ≥5.

Regardless of discipline, there has been rapid adoption of distance learning in graduate medical education.30–39 Virtual learning can be quickly adopted for didactics and scaled to meet demand. Henderson et al. 33 used an online platform to provide instruction for attending physicians at the pandemic’s onset, helping prepare faculty for redeployment outside their specialty. Yet, distance learning cannot replace the inpatient clinical experience and in-person exposure necessary for procedural competence.34,35 Although lecture recordings are commonly used in medical schools, whether synchronous virtual learning in graduate medical education is as effective as in-person instruction in terms of attention, retention, and interaction is unknown, and should be studied. Clinical restrictions (e.g., removing fellows from dialysis service) may affect fellows’ progress to unsupervised practice and procedural competence given nephrology fellowship’s 2-year training window.31,34,39 Similarly, with the pandemic’s course uncertain, it is unknown how programs can address staffing and educational demands if the management approaches reported in our study—shifting COVID-19 consults to telehealth or away from fellows to attendings—are continued.

One quarter of respondents said the pandemic had negatively affected their clinical experiences, board preparation, and research, lower than the 69% of cardiology fellows concerned about completing requirements.36 Yet, most respondents perceived themselves as prepared for unsupervised practice on fellowship completion (fellows 86%; graduates 90%). This perception is not an objective measure of respondents’ true state of preparedness but may reflect programs’ successes in advancing their trainees to independent practice. In total, 84% believed their program had sustained their education during the pandemic, although substantial challenges remain. Fellows training in New York City saw their academic activities put on hold as they suddenly found themselves overwhelmed by COVID-19 in March 2020, and such disruptions may continue to recur on the basis of local positivity rates.40 Whereas 11% of respondents were redeployed, this is lower than other subspecialty trainees and may change.37 This situation could complicate fellows’ progress through their ACGME Milestones. Impairments to advancing their research reported by 28% in our study will likely remain in the near term in both the bench and clinic, as institutions prioritize safety measures for laboratory staff and patients.38,41,42 However, the unexpected increase in respondents recommending nephrology (87% versus 72%–80% observed in 2014–2019)20 may reflect the esprit de corps of a specialty on the front lines of a pandemic response.35,40,43

Respondents reported a broad adoption of telehealth in their fellowships to comply with social distancing and other safety requirements. Telehealth has been effective in providing nephrology care to patients in sparsely populated regions of the United States and Australia, where geographic distance is a barrier to accessing specialized care.44 It can also help improve access for those with limited resources for travel and/or high disease burden and reduce barriers to the adequacy of disease management.45 Although initial literature has shown comparable educational efficacy in medical school electives and clerkships,46,47 it is unknown if telehealth can provide clinical experiences as effective as in-person interactions needed in graduate medical education.48 Of the other new patient care approaches reported by fellows, the use of acute start peritoneal dialysis to manage patients with COVID-19 has also been reported in the literature.49–51

Our finding that a lower proportion of respondents met the threshold for distress than in the RWBI instrument’s validation cohort was unexpected. The observed prevalence was also lower than reported in other subspecialty fellows (50% of intensivist trainees screened positive for depression),52 global residents/fellows (burnout range 39%–66%),53 or health care workers in the COVID-19 pandemic (anxiety range 23.2%–44.6%; depression range 22.8%–50.4%).9,10 The lower rate could be attributable to our survey frame, which comprised adult and pediatric fellows, the latter of whom have experienced lower volumes of patients with COVID-19 and demonstrated lower distress prevalence (13% versus 15% for adult fellows). With the substantial personal risk health care providers face in the pandemic, coupled with the fear of COVID-19 infection and transmission to their families, we anticipated a higher proportion of respondents would meet the distress threshold, especially given 13% lived with a family member at high risk for COVID-19 morbidity or mortality.35 Although fellows’ health could also affect QOL and distress threshold, questions about personal risk status were excluded due to their sensitive nature. An RWBI ≥5 correlates with a four-fold increased burnout risk, yet our observed proportion of distress (15%) was substantially lower than the 30% of nephrology fellows meeting the Maslach Burnout Inventory criteria in a prepandemic survey.19,52,53 Although the RWBI is a composite measure of physician distress that correlates with burnout and other factors, it may not be a directly comparable to the Maslach Burnout Inventory or other assessments.52,53

There were no significant associations between demographic variables and meeting the distress threshold. Although this may be due to the small numbers of respondents in demographic subgroups, it is possible distress is such a unique personal experience, it cannot be identified by such coarse demographic variables alone. The uneven geographic distribution and timing of virus surges could also account for the lower distress rate in aggregate. An increased sense of unity born from adversity in addressing a global pandemic40 and the prominent role nephrologists have played leading to an increase in the perceived value of the specialty may also be factors. The improvements in sense of community and mentor relationships observed in our study may also contribute an ameliorating effect.

Despite the comparatively low level of occupational stress we observed, respondents reported higher incidences of personal stress that were adversely related to an outcome of meeting RWBI’s distress threshold. Because we chose not to ask detailed questions about home life and family structure, our measures assessing pandemic-related effects on personal life may not be sufficiently granular or comprehensive to accurately determine their contributions to distress risk. The prevalence of graduates having difficulty finding a satisfactory position (37%) was within the range observed in previous surveys (38%–61%), as was the higher proportions of IMGs (72%) experiencing adversity in their job search.54 This is concerning, because IMGs comprise the majority of nephrology fellows—and internal medicine residents—and make important contributions to the US health care system. Furthermore, our survey was performed relatively early in the pandemic, and it is likely the continued personal and professional stresses of the pandemic will cause the level of burnout to increase as further surges occur. Continuing to monitor fellows for signs of distress should be a priority for training programs.

Our study has several limitations. Participants were representative of nephrology fellowship locations and demographic variables, yet our results may not be representative of those who were invited but did not participate, and thus may not generalize to the fellow or recent graduate population as a whole. This gap may have been exacerbated by the study’s emotionally sensitive topic area, inaccuracies in contact information, and survey invitations filtered by institutional firewalls. Although the survey was distributed 6 months after the initial COVID-19 surge in the United States, the results could still be tainted by recall bias. This likely accounts for some of the differences between graduates and current fellows on some responses. However, we cannot be certain that fellows working in regions with high hospitalization rates for patients with COVID-19 during the survey administration were less likely to experience recall bias. “Telehealth” was also not defined across patient care settings, which may lower the reliability of our results. Specifically, it is unknown how these items were interpreted and whether they accurately captured the mode of interaction for each setting. Finally, this study largely assesses fellows’ perceptions of their training. We cannot infer their true readiness for independent practice on the basis of these data. This study was not designed to assess evolution of modalities such as telehealth and remote learning over time. However, these data provide critical insight for designing future studies to measure the effectiveness of remote-learning modalities and telehealth.

This study also has several strengths, including the robust response rate, especially during the course of a pandemic when physicians’ time demands are intensified. Our response rate (42%) is higher than some other physician web-based surveys, which can be 10% lower than for the general public.55,56 The survey was also timed to reduce recall bias among respondents who experienced the initial COVID-19 surge in March/April 2020 and be completed before flu season and anticipated surge coincident with seasonal changes. Finally, our study was nationally representative of current nephrology fellowship program locations and demographics.26

Our results indicate nephrology fellowships and their sponsoring institutions should closely monitor their trainees for distress and ensure they have access to adequate support infrastructure. Agrawal et al. 19 outlined strategies to address burnout, including faculty awareness, curricula on emotional wellbeing and communication skills, and providing access to mental health resources, especially as the pandemic’s path—and duration—remain unknown. Although 34% of respondents indicated their sense of community within their fellowship had improved since the pandemic began, and has brought forth a sense of unity among fellows, attendings, and allied professionals, strategies to bolster this esprit de corps should be implemented. Programs must continue to balance the needs for safety, service, and education, which will allow fellows to develop a foundation of clinical competency, institutions to fulfill their clinical missions, and the field of nephrology to advance through the scholarly and service work of fellows.

Disclosures

K.A. Pivert reports having an ownership interest in iShares Gold Trust ETF and is an employee of the American Society of Nephrology. H.H. Shah is an editorial board member of the American Journal of Therapeutics. J.S. Waitzman’s spouse is an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals. L. Chan reports receiving research funding from National Institutes of Health. S.M. Halbach reports honoraria from Horizon Therapeutics; and Other Interests/Relationships with UpToDate. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

L. Chan is supported by National Institutes of Health award K23DK124645. J.S. Waitzman is supported by National Institutes of Health award T32 DK007199 and by a Ben J. Lipps Research Fellowship from the American Society of Nephrology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating nephrology fellows and 2020 nephrology graduates for contributing their insights to this research. They also acknowledge the time and assistance provided by nephrology program coordinators, training program directors, and associate training program directors. A special thanks to American Society of Pediatric Nephrology Executive Director Ms. Connie Mackay and ASN Leadership Development Coordinator Ms. Molly Jacob for their contributions to this study, and to Ms. Adrienne Lea, Mr. Tod Ibrahim, and Ms. Laura McCann for their critical review of the draft.

All authors designed the study and developed the survey instrument. Kurtis A. Pivert and Stephen M. Sozio oversaw survey dissemination and analyzed the data. All authors drafted the manuscript or revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable to the work.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2020111636/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplementa l Material I. Survey instrument.

Supplemental Material II: Supplemental Figure 1. Respondent locations by COVID-19 hospitalizations and MMWR week.

Supplemental Material III. Georgaphic variation in telehealth adoption and management of patients with COVID-19.

Supplemental Table 1. Inpatient consults and telehealth by region.

Supplemental Table 2. Outpatient consults and telehealth by region.

Supplemental Table 3. Outpatient dialysis and telehealth by region.

Supplemental Table 4. Management of patients with COVID-19 by region.

References

- 1. Kant S, Menez SP, Hanouneh M, Fine DM, Crews DC, Brennan DC, et al.: The COVID-19 nephrology compendium: AKI, CKD, ESKD and transplantation. BMC Nephrol 21: 449, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nadim MK, Forni LG, Mehta RL, Connor MJ Jr, Liu KD, Ostermann M, et al.: COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury: Consensus report of the 25th Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) workgroup [published correction appears in Nat Rev Nephrol 16: 765, 2020 10.1038/s41581-020-00372-5]. Nat Rev Nephrol 16: 747–764, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ikizler TA, Kliger AS: Minimizing the risk of COVID-19 among patients on dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol 16: 311–313, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldfarb DS, Benstein JA, Zhdanova O, Hammer E, Block CA, Caplin NJ, et al.: Impending shortages of kidney replacement therapy for COVID-19 patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 880–882, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, Chan L, Mathews KS, Melamed ML, et al.; STOP-COVID Investigators: Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med 180: 1–12, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flythe JE, Assimon MM, Tugman MJ, Chang EH, Gupta S, Shah J, et al.; STOP-COVID Investigators: Characteristics and outcomes of individuals with pre-existing kidney disease and COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 77: 190–203.e1, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Meester J, De Bacquer D, Naesens M, Meijers B, Couttenye MM, De Vriese AS; NBVN Kidney Registry Group : Incidence, characteristics, and outcome of COVID-19 in adults on kidney replacement therapy: A regionwide registry study. J Am Soc Nephrol 32[2]: 385–396, 2021. 10.1681/ASN.2020060875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ng JH, Hirsch JS, Wanchoo R, Sachdeva M, Sakhiya V, Hong S, et al.; Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium and the Northwell Nephrology COVID-19 Research Consortium: Outcomes of patients with end-stage kidney disease hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int 98: 1530–1539, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al.: Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 3: e203976, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P: Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 88: 901–907, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Geara AS, Neyra JA: COVID-19: Nephrology preparedness checklist. Clin Nephrol 94: 14–17, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lew SQ, Wallace EL, Srivatana V, Warady BA, Watnick S, Hood J, et al.: Telehealth for home dialysis in COVID-19 and beyond: A perspective from the American society of nephrology COVID-19 home dialysis subcommittee. Am J Kidney Dis 77: 142–148, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. El Shamy O, Tran H, Sharma S, Ronco C, Narayanan M, Uribarri J: Telenephrology with remote peritoneal dialysis monitoring during coronavirus disease 19. Am J Nephrol 51: 480–482, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rizo-Topete LM, Husain-Syed F, Ronco C: Reinforcing the team: A call to critical care nephrology in the COVID-19 epidemic. Blood Purif, 2020, Published ahead of print 10.1159/000510881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ross MJ, Braden G; ASN Match Committee: Perspectives on the nephrology match for fellowship applicants. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1715–1717, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jhaveri KD, Sparks MA, Shah HH, Khan S, Chawla A, Desai T, et al.: Why not nephrology? A survey of US internal medicine subspecialty fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 540–546, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sozio SM, Pivert KA, Shah HH, Chakkera HA, Asmar AR, Varma MR, et al.: Increasing medical student interest in nephrology. Am J Nephrol 50: 4–10, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nair D, Pivert KA, Baudy A 4th, Thakar CV: Perceptions of nephrology among medical students and internal medicine residents: A national survey among institutions with nephrology exposure. BMC Nephrol 20: 146, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agrawal V, Plantinga L, Abdel-Kader K, Pivert K, Provenzano A, Soman S, et al.: Burnout and emotional well-being among nephrology fellows: A national online survey. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 675–685, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pivert K, Boyle S, Chan L, McDyre K, Mehdi A, Norouzi S, et al.: 2019 Nephrology Fellow Survey—Results and Insights, Washington, DC, ASN Alliance for Kidney Health, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dyrbye LN, Satele D, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD: Ability of the physician well-being index to identify residents in distress. J Grad Med Educ 6: 78–84, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maslach C, Leiter MP: Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 15: 103–111, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, D’Agostino McGowan L, François R, et al.: Welcome to the tidyverse. J Open Source Softw 4: 1686, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wickham H, Miller E: haven: Import and Export ‘SPSS’, ‘Stata’ and ‘SAS’ Files. R package version 2.3.1, 2020. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=haven. Accessed October 19, 2020

- 25. Sjoberg DD, Curry M, Hannum M, Whiting K, Zabor EC: Gtsummary: Presentation-ready data summary and analytic result tables. R package version 1.3.5. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gtsummary. Accessed November 2, 2020

- 26. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: Data Resource Book. Academic Year 2019–2020, Chicago, IL, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dong E, Du H, Gardner L: An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis 20: 533–534, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. The COVID Tracking Project at: The Atlantic. Available at: https://covidtracking.com/data/download. Accessed January 6, 2021

- 29. Preparedness Coronavirus and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020. Public Law No: 116-123, 134 STAT. 146 2020. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ123/PLAW-116publ123.pdf. Accessed February 6, 2021.

- 30. Barberio B, Massimi D, Dipace A, Zingone F, Farinati F, Savarino EV: Medical and gastroenterological education during the COVID-19 outbreak. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 17: 447–449, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hilburg R, Patel N, Ambruso S, Biewald MA, Farouk SS: Medical education during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: Learning from a distance. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 27: 412–417, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gaffney Brian, O’Carroll Orla, Conroy Finbarr, Butler Marcus W, Keane Michael P, McCarthy Cormac: The impact of COVID-19 on clinical education of internal medicine trainees. Ir J Med Sci, 2020. 10.1007/s11845-020-02350-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Henderson D, Woodcock H, Mehta J, Khan N, Shivji V, Richardson C, et al.: Keep calm and carry on learning: Using Microsoft Teams to deliver a medical education programme during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future Healthc J 7: e67–e70, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. DeFilippis EM, Stefanescu Schmidt ACS, Reza N. Adapting the educational environment for cardiovascular fellows-in-training during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 75: 2630–2634, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coffman TM, Chan CM, Choong LHL, Curran I, Tan HK, Tan CC: Perspectives on COVID-19 from Singapore: Impact on ESKD care and medical education. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 2242–2245, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rao P, Diamond J, Korjian S, Martin L, Varghese M, Serfas JD, et al.; American College of Cardiology Fellows-in-Training Section Leadership Council: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cardiovascular fellows-in-training: A national survey. J Am Coll Cardiol 76: 871–875, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Clarke Kofi, Bilal Mohammad, Sánchez-Luna Sergio A, Dalessio Shannon, Maranki Jennifer L, Siddique Shazia Mehmood: Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Training: Global Perceptions of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Fellows in the USA. Dig Dis Sci, 2020. 10.1007/s10620-020-06655-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Westerman ME, Tabakin AL, Sexton WJ, Chapin BF, Singer EA: Impact of CoVID-19 on resident and fellow education: Current guidance and future opportunities for urologic oncology training programs. Urol Oncol, 2020, Published ahead of print 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shi J, Miskin N, Dabiri BE, DeSimone AK, Schaefer PM, Bay C, et al.: Quantifying impact of disruption to radiology education during the COVID-19 pandemic and implications for future training. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol, 2020, Published ahead of print 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2020.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hindi J, Fuca N, Sanchez Russo L: Beware the ides of March: A fellow’s perspective on surviving the COVID-19 pandemic. Kidney360. November 2020, 1 (11) 1316-1318; DOI: 10.34067/KID.0005442020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41. Omary MB, Eswaraka J, Kimball SD, Moghe PV, Panettieri RA Jr, Scotto KW: The COVID-19 pandemic and research shutdown: Staying safe and productive. J Clin Invest 130: 2745–2748, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Korbel JO, Stegle O: Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on life scientists. Genome Biol 21: 113, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hirsch JS, Uppal NN, Finger M, Barnett R, Fishbane S, Ng JH; Northwell Nephrology COVID-19 Research Consortium and the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium: The surge in nephrology consultations and inpatient dialysis services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Nephrol 94: 322–325, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rohatgi R, Ross MJ, Majoni SW: Telenephrology: Current perspectives and future directions. Kidney Int 92: 1328–1333, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jain G, Ahmad M, Wallace EL: Technology, telehealth, and nephrology: The time is now. Kidney360 1: 834–836, 2020. 10.34067/KID.0002382020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Durfee SM, Goldenson RP, Gill RR, Rincon SP, Flower E, Avery LL: Medical student education roadblock due to COVID-19: Virtual radiology core clerkship to the rescue. Acad Radiol 27: 1461–1466, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kuo M, Poirier MV, Pettitt-Schieber B, Pujari A, Pettitt B, Alabi O, et al.: Efficacy of vascular virtual medical student education during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Vasc Surg 73: 348–349, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Crews DC, Purnell TS: COVID-19, racism, and racial disparities in kidney disease: Galvanizing the kidney community response. J Am Soc Nephrol 31: 1–3, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sourial MY, Sourial MH, Dalsan R, Graham J, Ross M, Chen W, et al.: Urgent peritoneal dialysis in patients with COVID-19 and acute kidney injury: A single-center experience in a time of crisis in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 76: 401–406, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nagatomo M, Yamada H, Shinozuka K, Shimoto M, Yunoki T, Ohtsuru S: Peritoneal dialysis for COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury. Crit Care 24: 309, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. El Shamy O, Sharma S, Winston J, Uribarri J: Peritoneal dialysis during the Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Acute inpatient and maintenance outpatient experiences. Kidney Med 2: 377–380, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sharp M, Burkart KM, Adelman MH, Ashton RW, Daugherty Biddison L, Bosslet GT, et al.; Consensus Expert Panel (CEP) Members: A national survey of burnout and depression among fellows training in pulmonary and critical care medicine: A special report by the association of pulmonary and critical care medicine program directors. Chest 159: 733–742, 2021. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cravero AL, Kim NJ, Feld LD, Berry K, Rabiee A, Bazarbashi N, et al.: Impact of exposure to patients with COVID-19 on residents and fellows: An international survey of 1420 trainees. Postgrad Med J, 2020, Published ahead of print 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Quigley L, Salsberg E, Collins A: Report on the 2018 Survey of Nephrology Fellows, Washington, DC, American Society of Nephrology, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA: Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol 50: 1129–1136, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, Noseworthy T, Beck CA, Dixon E, et al.: Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 15: 32, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.