Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate changes in the gingival thickness (GT) and keratinized gingival width (KGW) of the maxillary and mandibular central and lateral incisors and canines after fixed orthodontic treatment and their association with sagittal tooth movement (STM).

Materials and Methods

In this study of both arches, 60 periodontally healthy subjects who had completed fixed orthodontic treatment were included. Using pretreatment and posttreatment lateral cephalograms, STM of the maxillary (1-NA angle and distance, and 1-SN angle) and mandibular (1-NB angle and distance, and IMPA angle) incisors were evaluated to divide the subjects into protrusion and retrusion groups. Pretreatment and posttreatment GT was identified via transgingival probing, and KGW was calculated from the free gingival margin to the mucogingival junction.

Results

The intragroup pretreatment and posttreatment comparison results showed a significant decrease in the GT of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth in the protrusion and retrusion groups and a decrease in the KGW of the maxillary lateral incisors in the protrusion group. Pearson correlation coefficient analyses for maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth revealed that the GT changes were not significantly associated with STM. However, a positive correlation existed between the KGW of tooth numbers 13 and 41 and STM.

Conclusions

STM was not significantly associated with decreased GT of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth, but it was positively correlated with the KGW of tooth numbers 13 and 41.

Keywords: Gingival thickness, Keratinized gingival width, Tooth movement

INTRODUCTION

Gingival recession is defined as the clinical exposure of the root surface via the atypical displacement of the marginal tissue from the cemento-enamel junction.1,2 Although the etiology remains unclear, alveolar bone defects (such as dehiscences and fenestration) that relate to anatomical, pathological, and physiological factors are a prerequisite for developing gingival recession.2,3 Orthodontic tooth movements exceeding the alveolar bone's anatomic limits via the application of uncontrolled forces can cause dehiscences associated with physiological factors.1,2,4

The distance from the cemento-enamel junction to the bone crest is more than 2 mm in dehiscences, which are frequent in normal populations.5,6 Previously published studies evaluated the marginal alveolar bone levels with pretreatment and posttreatment cone-beam computed tomographs (CBCTs). They showed a decrease in bone height, and an increase in the frequency of dehiscence occurred after orthodontic treatment, depending on the direction of force applied.6–8 The lower prevalence of gingival recession, which would be expected to be higher because of the high frequency of dehiscence, is probably related to gingival biotype.5,9,10 A thin gingival biotype is characterized by delicate soft tissue with minimal attachment and is associated with a tendency for gingival recession in areas without proper alveolar bone support because of the susceptibility to trauma and inflammation.4,9

During orthodontic tooth movement, the soft-tissue attachment moves together with the tooth and causes the gingiva to narrow in apicocoronal height and lessen in buccolingual thickness.4,9,11 Hence, tooth movements (especially in the buccolingual direction) must be performed while accounting for gingiva in the pressure zone of the tooth.4,11

A review of the literature revealed that the gingival thickness (GT) and keratinized gingival width (KGW) changed because of orthodontic treatment, and this association with tooth movement has not been evaluated previously. In the light of this, the aims of this study were to evaluate changes in the GT and KGW of the maxillary and mandibular central and lateral incisors and canines after orthodontic treatment and to evaluate the association with sagittal tooth movement (STM). The alternative (H1) hypothesis was that the gingiva's thickness and keratinized width varied based on the STM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study including both maxillary and mandibular dental arches, 60 subjects who presented to the Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Van Yüzüncü Yil University, between June 2016 and June 2017 and completed fixed orthodontic treatment with or without extraction using a straight-wire technique and 0.018-inch slot Roth brackets were included. Approval to conduct this study was obtained from the research ethics committee of Van Yüzüncü Yil University's Faculty of Medicine (20.11.2019/04). After they were provided with a detailed description of the study, every participant signed informed consent prepared according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

The exclusion criteria included previous functional orthopedic and/or fixed orthodontic treatment, severe skeletal discrepancy (ANB <−1 and ANB >5), buccally positioned maxillary and mandibular canines, lingual or palatally positioned maxillary and mandibular lateral incisors, gingival swelling, destructive periodontal disease, baseline recession, systemic problems with related medications, antibiotics taken within the past 6 months, pregnancy and lactation, dental structure disorders, congenital anomalies, crowns and extensive restorations, and smoking. Periodontally healthy subjects with complete permanent dentition, in need of fixed orthodontic treatment with or without extraction and for whom incisor protrusion/proclination and retrusion/retroclination were planned, were included in this study.

After analyzing orthodontic material collected before treatment, treatment was planned while considering many factors, such as space deficiency, incisor positions, and interarch relationships. Subjects for whom incisor protrusion/proclination and retrusion/retroclination were planned during treatment were included in the protrusion and retrusion groups, respectively. For each maxillary and mandibular dental arch, the protrusion and retrusion groups comprised an equal number of subjects. Attention was paid to match the chronological age and mean treatment duration of subjects in both groups.

Pretreatment periodontal parameters, GT and KGW, were evaluated just before the application of the orthodontic appliance, and posttreatment evaluations were performed 6 months after removing the orthodontic appliances. The same investigator (Dr Kaya) performed all measurements.

A full periodontal examination of the subjects was performed using a periodontal probe (BPW, Osung MND, Seoul, Korea). The plaque index (PI; Silness and Löe), gingival index (GI; Löe and Silness), and probing depth (PD) of the periodontal pockets were recorded.

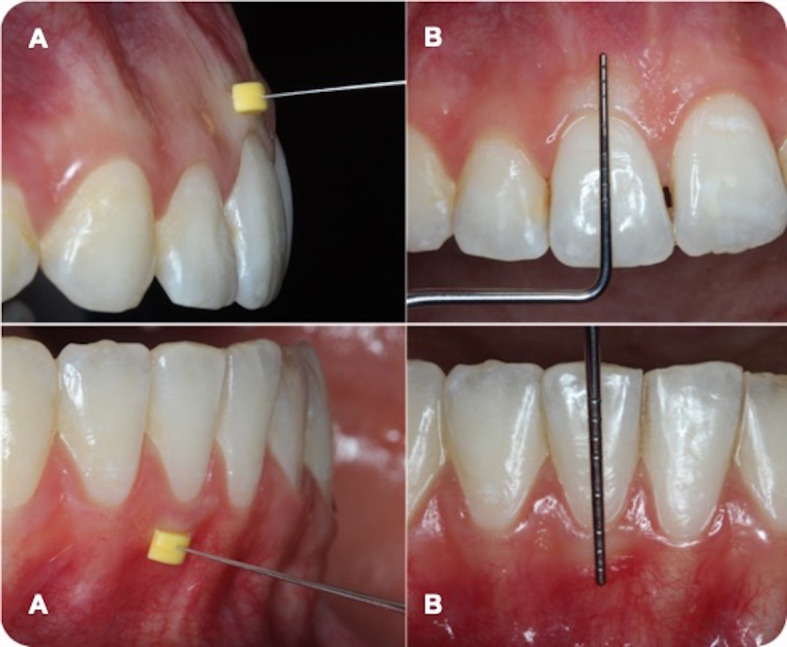

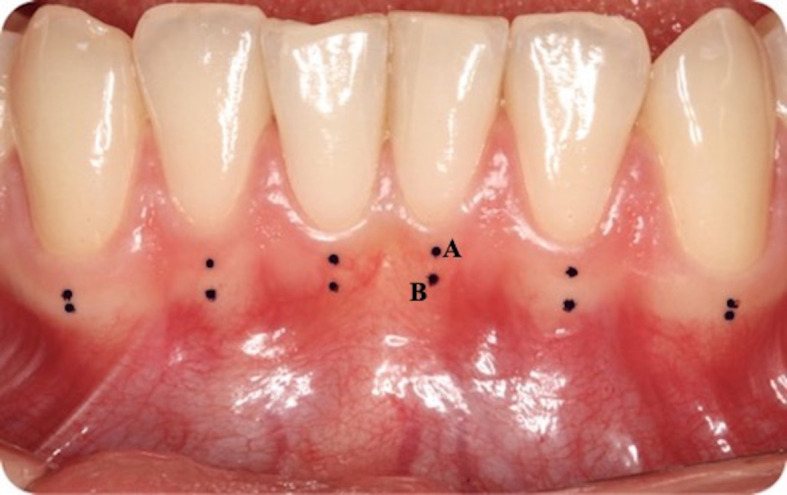

The GTs were examined along the long axis of the midlabial surfaces of central and lateral incisors and canines in the maxilla and mandible (Figure 1A). All measurements were performed via transgingival probing under topic anesthesia (xylocaine spray, Vemcain, 10% lidocaine; Vem, Istanbul, Turkey) at two points: apical to the free gingival margin (Figure 2A) and coronal to the mucogingival junction (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Measurements of the gingival thickness (A) and keratinized gingival width (B) of maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth.

Figure 2.

Gingival thickness measurement points: apical to the free gingival margin (A) and coronal to the mucogingival junction (B).

A 10-mm endodontic spreader (G-Star Medical, Guangdong, China) with a silicone stopper was positioned perpendicularly to the long axis of the measurement points and inserted into the soft tissue until meeting resistance from the alveolar bone. Excessive force would cause the spreader to penetrate the soft tissue and go through the alveolar bone, so care was taken to apply light forces. The penetration depth between the tip of the endodontic spreader and silicone stopper was recorded using a digital caliper with 0.01-mm sensitivity (Mitutoyo Corporation, Kanagawa, Japan). For each region, the measurements were repeated twice at 10-minute intervals. The GT of each region was determined from the mean of the two measurements. The GT of each tooth was determined via the mean of GT values from the apical to the free gingival margin and from the coronal to the mucogingival junction.

The KGWs of the central and lateral incisors and of the canines were measured clinically using a periodontal probe (BPW, Osung MND). The measurements were performed from the free gingival margin to the mucogingival junction parallel to the long axis of the tooth at the midlabial root surface (Figure 1B).

The intraexaminer reliability of the researcher was analyzed for GT and KGW in 15 patients and found to be high (Pearson correlation coefficient: 0.847, P < .001).

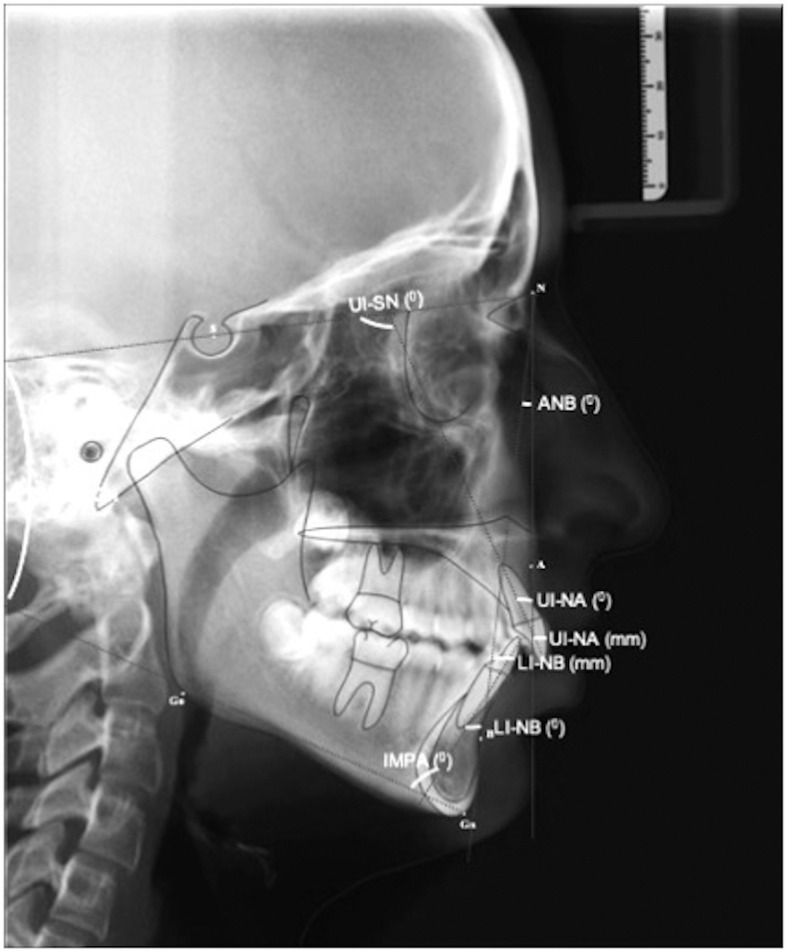

Using the same Sirona Orthophos XG imaging system (Bensheim, Germany), cephalometric radiographs were taken before orthodontic treatment and immediately after removing the orthodontic appliances, in centric occlusion with the lips lightly sealed. During imaging, each subject's head was stabilized by positioning the ear rods in the external auditory meatus with the Frankfurt plane parallel to the floor and the sagittal plane perpendicular to the X-ray's path. For blinding, the second observer (Dr Tunca) imported the cephalogram images into the Nemoceph NX 2005 (Nemotec, Madrid, Spain) program via numbers without using patient names or groups. Then, the main observer (Dr Kaya) performed the digital tracing. The linear and angular skeletal measurements used in this study are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Angular and linear cephalometric measurements used in this study.

To define the intraobserver error, the main observer retraced 30 randomly selected lateral cephalometric radiographs. More than 2 weeks elapsed between the first and second tracings. The random measurement error was calculated via Dahlberg's formula. The error values ranged from 0.12 to 0.26.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for the normally distributed variables were presented as means and standard deviations. Normality assumptions were analyzed with a Kolmogrov-Smirnov test. After the normality test, a Student t-test was used to compare the protrusion and retrusion groups. In addition, a paired t-test was performed to evaluate each group's pretreatment and posttreatment differences. For determination of linear relationships among the variables, a Pearson correlation analysis was carried out. All statistical analyses were done via SPSS software for Windows (version 22.0; IBM, Armonk, NY) with a statistical significance of 5%.

RESULTS

For maxillary and mandibular dental arches, the proportion of females in the protrusion and retrusion groups was higher than males. For the mean age and the mean treatment duration, however, no significant differences were found between the protrusion and retrusion groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the Study Population for Maxillary and Mandibular Dental Arches*

| Group |

Females (n) |

Males (n) |

Age, y (Mean ± SD) |

Mean Treatment Duration, y (Mean ± SD) |

| Maxillary dental arch | ||||

| Protrusion | 18 | 12 | 15.78 ± 2.35 | 2.82 ± 0.47 |

| Retrusion | 23 | 7 | 16.13 ± 2.49 | 3.18 ± 0.49 |

| Total | 41 | 19 | 15.96 ± 2.41 | 3.00 ± 0.51 |

| P | .704 | .626 | ||

| Mandibular dental arch | ||||

| Protrusion | 16 | 14 | 16.00 ± 2.90 | 2.89 ± 0.50 |

| Retrusion | 24 | 6 | 17.37 ± 3.45 | 3.16 ± 0.57 |

| Total | 40 | 20 | 16.65 ± 3.23 | 3.02 ± 0.55 |

| P | .086 | .647 | ||

P < .05.

The intragroup pretreatment and posttreatment comparisons of PI, GI, and PD measurements in the protrusion and retrusion groups exhibited nonsignificant differences for the maxillary and mandibular dental arches. The intergroup comparison results before and after orthodontic treatment were also not significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pretreatment and Posttreatment Intragroup and Intergroup Comparisons of Plaque Index, Gingival Index, and Probing Depth Measurements for Maxillary and Mandibular Dental Arches

| Group |

Maxillary Dental Arch |

Mandibular Dental Arch |

||||

| Pretreatment, Mean ± SD |

Posttreatment, Mean ± SD |

Pa |

Pretreatment, Mean ± SD |

Posttreatment, Mean ± SD |

Pa |

|

| Plaque index | ||||||

| Protrusion | 1.05 ± 0.30 | 0.92 ± 0.48 | .151 | 1.06 ± 0.34 | 0.94 ± 0.50 | .234 |

| Retrusion | 1.07 ± 0.23 | 1.06 ± 0.40 | .873 | 1.08 ± 0.23 | 1.09 ± 0.37 | .812 |

| Total | 1.06 ± 0.26 | 0.99 ± 0.44 | .208 | 1.07 ± 0.29 | 1.01 ± 0.45 | .339 |

| Pb | .791 | .226 | 0.833 | 0.178 | ||

| Gingival index | ||||||

| Protrusion | 0.68 ± 0.39 | 0.69 ± 0.38 | .917 | 0.62 ± 0.37 | 0.66 ± 0.41 | .290 |

| Retrusion | 0.58 ± 0.44 | 0.72 ± 0.41 | .097 | 0.57 ± 0.40 | 0.64 ± 0.43 | .300 |

| Total | 0.63 ± 0.42 | 0.71 ± 0.39 | .179 | 0.59 ± 0.38 | 0.65 ± 0.41 | .145 |

| Pb | .363 | .760 | 0.611 | 0.876 | ||

| Probing depth | ||||||

| Protrusion | 1.79 ± 0.40 | 1.76 ± 0.31 | .763 | 1.84 ± 0.40 | 1.78 ± 0.29 | .451 |

| Retrusion | 1.74 ± 0.53 | 1.76 ± 0.33 | .834 | 1.67 ± 0.51 | 1.73 ± 0.35 | .609 |

| Total | 1.77 ± 0.46 | 1.76 ± 0.32 | .964 | 1.76 ± 0.46 | 1.75 ± 0.31 | .970 |

| Pb | .691 | .977 | 0.167 | 0.582 | ||

Indicates differences between the pretreatment and posttreatment measurements.

Indicates differences between the protrusion and retrusion groups.

The means, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum values for pretreatment and posttreatment cephalometric measurements (and for the differences between these two measurements) are presented in Table 3. For the maxillary dental arch, the protrusion group showed mean increases of 2.43 ± 1.14 mm, 8.06° ± 3.25°, and 7.23° ± 3.21°, and the retrusion group showed mean decreases of 3.49 ± 2.04 mm, 7.93° ± 5.77°, and 8.33° ± 5.77° in 1-NA distance, 1-NA angle, and 1-SN angles, respectively. The mandibular dental arch 1-NB distance, 1-NB angle, and IMPA angle showed a mean increase of 2.07 ± 1.06 mm, 5.45° ± 3.63°, and 5.48° ± 4.39° and a mean decrease of 1.80 ± 0.88 mm, 6.43° ± 4.19°, and 6.40° ± 4.07° in the protrusion and retrusion groups, respectively.

Table 3.

Pretreatment and Posttreatment Cephalometric Measurements of Protrusion and Retrusion Groups for Maxillary and Mandibular Dental Arches

| Group |

Pretreatment |

Posttreatment |

Pre- and Posttreatment Differences |

||||||

| Mean ± SD |

Min |

Max |

Mean ± SD |

Min |

Max |

Mean ± SD |

Min |

Max |

|

| Maxillary dental arch | |||||||||

| ANB, ° | |||||||||

| Protrusion | 2.63 ± 2.20 | −2.0 | 5.0 | 2.27 ± 2.11 | −2.0 | 5.0 | −0.36 ± 0.71 | −2.0 | 1.0 |

| Retrusion | 3.90 ± 1.39 | −1.0 | 5.0 | 3.90 ± 1.32 | −1.0 | 5.0 | 0.06 ± 0.52 | −1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 3.27 ± 1.93 | −2.0 | 5.0 | 3.08 ± 1.93 | −2.0 | 5.0 | −0.15 ± 0.65 | −2.0 | 1.0 |

| SN/GoGn, ° | |||||||||

| Protrusion | 32.97 ± 4.06 | 26.0 | 38.0 | 32.93 ± 4.03 | 26.0 | 39.0 | −0.03 ± 1.80 | −5.0 | 3.0 |

| Retrusion | 34.30 ± 3.36 | 27.0 | 39.0 | 34.97 ± 2.95 | 28.0 | 38.0 | 0.83 ± 1.98 | −3.0 | 6.0 |

| Total | 33.63 ± 3.76 | 26.0 | 39.0 | 33.95 ± 3.65 | 26.0 | 39.0 | 0.40 ± 1.93 | −5.0 | 6.0 |

| 1-NA, mm | |||||||||

| Protrusion | 1.81 ± 2.63 | −3.7 | 6.6 | 4.24 ± 2.56 | −1.1 | 8.8 | 2.43 ± 1.14 | 1.0 | 5.0 |

| Retrusion | 4.12 ± 1.67 | 0.7 | 7.7 | 0.63 ± 2.24 | −5.1 | 4.8 | −3.49 ± 2.04 | −9.9 | −1.3 |

| Total | 2.96 ± 2.47 | −3.7 | 7.7 | 2.43 ± 3.00 | −5.1 | 8.8 | −0.52 ± 3.40 | −9.9 | 5.0 |

| 1-NA, ° | |||||||||

| Protrusion | 15.50 ± 7.64 | −2.0 | 31.0 | 23.57 ± 7.19 | 8.0 | 37.0 | 8.06 ± 3.25 | 2.0 | 15.0 |

| Retrusion | 22.43 ± 5.47 | 9.0 | 34.0 | 14.50 ± 6.92 | 1.0 | 26.0 | −7.93 ± 5.77 | −21.0 | −2.0 |

| Total | 18.96 ± 7.46 | −2.0 | 34.0 | 19.03 ± 8.36 | 1.0 | 37.0 | 0.65 ± 9.30 | −21.0 | 15.0 |

| 1-SN, ° | |||||||||

| Protrusion | 95.47 ± 7.11 | 75.0 | 108.0 | 102.70 ± 6.57 | 88.0 | 112.0 | 7.23 ± 3.21 | 2 | 13 |

| Retrusion | 102.33 ± 6.72 | 85.0 | 113.0 | 94.00 ± 8.14 | 76.0 | 108.0 | −8.33 ± 5.77 | −23 | −2 |

| Total | 98.90 ± 7.68 | 75.0 | 113.0 | 98.35 ± 8.54 | 76.0 | 112.0 | 0.40 ± 1.93 | −5.0 | 6.0 |

| Mandibular dental arch | |||||||||

| ANB, ° | |||||||||

| Protrusion | 3.61 ± 1.47 | −1.0 | 5.0 | 3.48 ± 1.67 | −1.0 | 6.0 | −0.12 ± 0.69 | −2.0 | 1.0 |

| Retrusion | 3.33 ± 1.92 | −2.0 | 5.0 | 3.23 ± 1.97 | −2.0 | 5.0 | −0.10 ± 0.60 | −2.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 3.48 ± 1.72 | −2.0 | 5.0 | 3.37 ± 1.81 | −2.0 | 6.0 | −0.11 ± 0.65 | −2.0 | 1.0 |

| SN/GoGn, ° | |||||||||

| Protrusion | 34.06 ± 3.54 | 27.0 | 38.0 | 33.97 ± 3.71 | 26.0 | 39.0 | −0.09 ± 1.60 | −5.0 | 3.0 |

| Retrusion | 33.40 ± 3.69 | 25.0 | 39.0 | 34.37 ± 3.59 | 24.0 | 38.0 | 0.96 ± 2.12 | −3.0 | 6.0 |

| Total | 33.75 ± 3.60 | 25.0 | 39.0 | 34.16 ± 3.63 | 24.0 | 39.0 | 0.41 ± 1.93 | −5.0 | 6.0 |

| 1-NB, mm | |||||||||

| Protrusion | 4.22 ± 2.16 | −2.0 | 7.3 | 6.30 ± 2.10 | 2.1 | 9.0 | 2.07 ± 1.06 | 0.5 | 5.8 |

| Retrusion | 5.62 ± 2.01 | 2.0 | 10.5 | 3.81 ± 1.85 | 1.1 | 9.2 | −1.80 ± 0.88 | −3.8 | −0.2 |

| Total | 4.88 ± 2.19 | −2.0 | 10.5 | 5.11 ± 2.33 | 1.1 | 9.2 | 0.22 ± 2.18 | −3.8 | 5.8 |

| 1-NB, ° | |||||||||

| Protrusion | 24.79 ± 6.58 | 12.0 | 36.0 | 30.24 ± 6.34 | 17.0 | 40.0 | 5.45 ± 3.63 | 2.0 | 17.0 |

| Retrusion | 29.87 ± 6.29 | 21.0 | 49.0 | 23.43 ± 5.21 | 17.0 | 40.0 | −6.43 ± 4.19 | −16.0 | −2.0 |

| Total | 27.21 ± 6.88 | 12.0 | 49.0 | 27.00 ± 6.72 | 17.0 | 40.0 | −0.20 ± 7.13 | −16.0 | 17.0 |

| IMPA, ° | |||||||||

| Protrusion | 91.60 ± 7.60 | 75.0 | 106.0 | 97.09 ± 7.21 | 83.0 | 112.0 | 5.48 ± 4.39 | 1.0 | 21.0 |

| Retrusion | 95.03 ± 7.25 | 83.0 | 118.0 | 89.90 ± 7.34 | 74.0 | 110.0 | −6.40 ± 4.07 | −14.0 | −1.0 |

| Total | 93.55 ± 7.64 | 75.0 | 118.0 | 93.38 ± 8.18 | 74.0 | 112.0 | −0.17 ± 7.31 | −14.0 | 21.0 |

The intergroup comparisons of GTs and KGWs of the maxillary and mandibular central and lateral incisors and canines exhibited nonsignificant differences both before and after orthodontic treatment. Intragroup pretreatment and posttreatment comparisons showed that the GTs of the maxillary and mandibular central and lateral incisors and canines significantly decreased and the KGWs significantly decreased only in the maxillary lateral incisors of the protrusion group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pretreatment and Posttreatment Intragroup and Intergroup Comparisons of Gingival Thickness and Keratinized Gingival Width for Maxillary and Mandibular Anterior Teeth

| Tooth No.a |

Group |

Gingival Thickness |

Keratinized Gingival Width |

||||

| Pretreatment, Mean ± SD |

Posttreatment, Mean ± SD |

Pa |

Pretreatment, Mean ± SD |

Posttreatment, Mean ± SD |

Pb |

||

| Maxillary dental arch | |||||||

| 11 | Protrusion | 1.26 ± 0.38 | 0.92 ± 0.20 | .001*** | 5.06 ± 1.65 | 4.60 ± 1.65 | .085 |

| Retrusion | 1.22 ± 0.30 | 0.86 ± 0.22 | .001*** | 4.91 ± 1.67 | 4.85 ± 1.48 | .864 | |

| Total | 1.24 ± 0.34 | 0.89 ± 0.21 | .001*** | 4.99 ± 1.65 | 4.72 ± 1.56 | .257 | |

| Pc | .678 | .322 | .729 | .540 | |||

| 12 | Protrusion | 1.22 ± 0.49 | 0.74 ± 0.17 | .001*** | 7.38 ± 2.74 | 6.38 ± 2.03 | .006** |

| Retrusion | 1.09 ± 0.40 | 0.76 ± 0.24 | .001*** | 7.55 ± 1.99 | 6.95 ± 2.11 | .277 | |

| Total | 1.16 ± 0.45 | 0.75 ± 0.21 | .001*** | 7.46 ± 2.38 | 6.66 ± 2.07 | .014* | |

| Pc | .283 | .793 | .789 | .294 | |||

| 13 | Protrusion | 0.81 ± 0.27 | 0.67 ± 0.17 | .033* | 4.25 ± 2.63 | 4.46 ± 2.66 | .356 |

| Retrusion | 0.84 ± 0.21 | 0.67 ± 0.19 | .002** | 4.28 ± 2.17 | 4.41 ± 1.74 | .746 | |

| Total | 0.82 ± 0.24 | 0.67 ± 0.18 | .001*** | 4.26 ± 2.39 | 4.44 ± 2.23 | .059 | |

| Pc | .610 | .932 | .958 | .932 | |||

| 21 | Protrusion | 1.28 ± 0.31 | 0.93 ± 0.21 | .001*** | 4.61 ± 1.61 | 4.78 ± 1.71 | .478 |

| Retrusion | 1.19 ± 0.27 | 0.85 ± 0.31 | .001*** | 4.76 ± 1.47 | 4.81 ± 1.58 | .888 | |

| Total | 1.23 ± 0.29 | 0.89 ± 0.27 | .001*** | 4.69 ± 1.53 | 4.80 ± 1.63 | .607 | |

| Pc | .254 | .214 | .709 | .938 | |||

| 22 | Protrusion | 1.24 ± 0.39 | 0.76 ± 0.17 | .001*** | 6.83 ± 2.01 | 6.03 ± 2.20 | .017* |

| Retrusion | 1.16 ± 0.45 | 0.76 ± 0.27 | .001*** | 6.86 ± 1.61 | 6.15 ± 1.82 | .077 | |

| Total | 1.20 ± 0.42 | 0.76 ± 0.22 | .001*** | 6.85 ± 1.81 | 6.09 ± 2.00 | .003** | |

| Pc | .456 | .980 | .946 | .824 | |||

| 23 | Protrusion | 0.79 ± 0.28 | 0.64 ± 0.18 | .006** | 4.07 ± 2.87 | 4.00 ± 1.74 | .876 |

| Retrusion | 0.84 ± 0.26 | 0.69 ± 0.24 | .011* | 4.13 ± 2.06 | 4.38 ± 1.54 | .547 | |

| Total | 0.82 ± 0.27 | 0.67 ± 0.21 | .001*** | 4.10 ± 2.48 | 4.19 ± 1.64 | .756 | |

| Pc | .484 | .368 | .918 | .371 | |||

| Mandibular dental arch | |||||||

| 31 | Protrusion | 0.67 ± 0.19 | 0.49 ± 0.16 | .001*** | 2.54 ± 1.18 | 2.78 ± 1.06 | .164 |

| Retrusion | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 0.44 ± 0.16 | .001*** | 2.76 ± 1.32 | 2.40 ± 1.09 | .094 | |

| Total | 0.67 ± 0.17 | 0.47 ± 0.16 | .001*** | 2.65 ± 1.24 | 2.60 ± 1.08 | .733 | |

| Pc | .889 | .266 | .487 | .158 | |||

| 32 | Protrusion | 0.81 ± 0.25 | 0.52 ± 0.19 | .001*** | 3.95 ± 1.34 | 3.78 ± 1.24 | .457 |

| Retrusion | 0.70 ± 0.22 | 0.47 ± 0.18 | .001*** | 3.68 ± 1.62 | 3.40 ± 1.44 | .098 | |

| Total | 0.76 ± 0.24 | 0.50 ± 0.18 | .001*** | 3.82 ± 1.47 | 3.60 ± 1.34 | .116 | |

| Pc | .059 | .245 | .472 | .257 | |||

| 33 | Protrusion | 0.64 ± 0.21 | 0.45 ± 0.18 | .001*** | 1.93 ± 1.13 | 2.21 ± 1.77 | .179 |

| Retrusion | 0.57 ± 0.16 | 0.38 ± 0.15 | .001*** | 1.76 ± 1.40 | 1.76 ± 1.47 | .999 | |

| Total | 0.61 ± 0.19 | 0.42 ± 0.17 | .001*** | 1.85 ± 1.26 | 2.00 ± 1.64 | .297 | |

| Pc | .167 | .124 | .591 | .286 | |||

| 41 | Protrusion | 0.74 ± 0.21 | 0.48 ± 0.18 | .001*** | 2.69 ± 1.38 | 2.97 ± 1.34 | .083 |

| Retrusion | 0.66 ± 0.15 | 0.44 ± 0.20 | .001*** | 3.03 ± 1.37 | 2.65 ± 0.94 | .093 | |

| Total | 0.70 ± 0.19 | 0.46 ± 0.19 | .001*** | 2.85 ± 1.37 | 2.81 ± 1.17 | .774 | |

| Pc | .104 | .465 | .336 | .283 | |||

| 42 | Protrusion | 0.83 ± 0.34 | 0.53 ± 0.21 | .001*** | 3.80 ± 1.51 | 3.59 ± 1.26 | .368 |

| Retrusion | 0.76 ± 0.19 | 0.46 ± 0.19 | .001*** | 3.93 ± 1.38 | 3.68 ± 1.20 | .138 | |

| Total | 0.80 ± 0.28 | 0.50 ± 0.20 | .001*** | 3.86 ± 1.44 | 3.63 ± 1.22 | .114 | |

| Pc | .285 | .211 | .723 | .768 | |||

| 43 | Protrusion | 0.62 ± 0.24 | 0.45 ± 0.20 | .001*** | 2.00 ± 1.39 | 2.13 ± 1.46 | .342 |

| Retrusion | 0.60 ± 0.18 | 0.41 ± 0.16 | .001*** | 1.61 ± 1.24 | 1.56 ± 1.25 | .759 | |

| Total | 0.61 ± 0.21 | 0.43 ± 0.18 | .001*** | 1.81 ± 1.32 | 1.86 ± 1.38 | .657 | |

| Pc | .725 | .357 | .255 | .104 | |||

Tooth numbering according to the FDI system.

Indicates differences between the protrusion and retrusion groups.

Indicates differences between the pretreatment and posttreatment measurements.

P < .05; ** P < .01; *** P < .001.

Pearson correlation coefficient analyses for the maxillary dental arch revealed that the differences observed in 1-NA distance, 1-NA angle, and 1-SN angle were not significantly associated with the changes in GT. A positive correlation was found only between the 1-NA and 1-SN angles and the KGW of tooth number 13. In addition, a positive correlation between the GTs of the central and lateral incisors and canines and a negative correlation between the GTs of the central incisors and the KGW of tooth number 13 were found (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients Between Cephalometric Measurements and Gingival Thickness and Keratinized Gingival Width for Maxillary Anterior Teetha

| Maxillary Dental Arch |

Gingival Thickness |

Keratinized Gingival Width |

||||||||||

| 11 |

12 |

13 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

|

| 1-NA, mm | −0.002 | −0.183 | 0.076 | −0.020 | −0.126 | 0.051 | 0.048 | 0.113 | 0.229 | 0.210 | 0.239 | 0.115 |

| 1-NA, ° | 0.009 | −0.178 | 0.118 | 0.037 | 0.066 | 0.050 | 0.018 | 0.089 | 0.262* | 0.173 | 0.233 | 0.131 |

| 1-SN, ° | −0.010 | −0.200 | 0.088 | 0.036 | −0.089 | 0.064 | 0.031 | 0.103 | 0.297* | 0.190 | 0.253 | 0.170 |

| Gingival thickness | ||||||||||||

| 11 | 1 | 0.442** | 0.351** | 0.480** | 0.354** | 0.286* | −0.168 | −0.125 | −0.427** | −0.143 | −0.162 | −0.075 |

| 12 | 1 | 0.435** | 0.486** | 0.549** | 0.274* | 0.161 | 0.253 | −0.102 | 0.100 | 0.179 | 0.099 | |

| 13 | 1 | 0.491** | 0.386** | 0.543** | 0.248 | 0.168 | −0.008 | 0.148 | −0.012 | 0.236 | ||

| 21 | 1 | 0.572** | 0.378** | −0.015 | 0.044 | −0.266* | 0.080 | 0.004 | 0.163 | |||

| 22 | 1 | 0.314* | −0.100 | 0.059 | −0.202 | −0.044 | 0.055 | 0.160 | ||||

| 23 | 1 | 0.153 | 0.172 | 0.074 | 0.150 | 0.042 | 0.222 | |||||

Tooth numbering according to the FDI system.

P < .05; ** P < .01; *** P < .001.

For the mandibular dental arch, the differences in 1-NB distance, 1-NB angle, and IMPA angle were not significantly associated with GT changes, but they had a positive correlation with the KGW of tooth number 41. In addition, a positive correlation between the GTs of the mandibular central and lateral incisors and of canine teeth was determined (Table 6).

Table 6.

Pearson Correlation Coefficients Between Cephalometric Measurements and Gingival Thickness and Keratinized Gingival Width for Mandibular Anterior Teetha

| Mandibular Dental Arch |

Gingival Thickness |

Keratinized Gingival Width |

||||||||||

| 31 |

32 |

33 |

41 |

42 |

43 |

31 |

32 |

33 |

41 |

42 |

43 |

|

| 1-NB, mm | 0.099 | −0.154 | −0.037 | −0.112 | −0.014 | 0.049 | 0.225 | −0.086 | 0.111 | 0.298* | 0.115 | 0.100 |

| 1-NB, ° | 0.116 | −0.002 | 0.020 | −0.032 | 0.034 | 0.053 | 0.186 | −0.121 | 0.125 | 0.295* | 0.125 | 0.030 |

| IMPA, ° | 0.071 | −0.030 | 0.008 | −0.033 | 0.026 | 0.091 | 0.174 | −0.119 | 0.041 | 0.297* | 0.114 | −0.001 |

| Gingival thickness | ||||||||||||

| 31 | 1 | 0.396** | 0.526** | 0.540** | 0.415** | 0.470** | 0.174 | 0.178 | 0.107 | 0.078 | 0.116 | 0.139 |

| 32 | 1 | 0.594** | 0.399** | 0.369** | 0.446** | −0.088 | 0.109 | −0.053 | −0.008 | −0.158 | 0.028 | |

| 33 | 1 | 0.579** | 0.461** | 0.641** | 0.006 | 0.111 | 0.174 | −0.008 | −0.095 | 0.089 | ||

| 41 | 1 | 0.551** | 0.479** | −0.093 | 0.017 | 0.149 | −0.081 | 0.019 | −0.131 | |||

| 42 | 1 | 0.314* | 0.062 | 0.029 | 0.117 | 0.015 | 0.155 | 0.213 | ||||

| 43 | 1 | −0.007 | −0.004 | −0.005 | −0.057 | −0.095 | 0.122 | |||||

Tooth numbering according to the FDI system.

P < .05; ** P < .01; *** P < .001.

DISCUSSION

This study's results showed a significant decrease, not associated with STM, in the GT of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth in the protrusion and retrusion groups after orthodontic treatment. In addition, a significant decrease in the KGW of maxillary lateral incisors in the protrusion group and a positive association between STM and the KGWs of tooth numbers 13 and 41 were observed. Therefore, the alternative hypothesis was partly rejected.

This was the first human study with a pretreatment and posttreatment comparative assessment of GT changes after tooth movement. Animal studies showed that the gingival tension induced by facial tooth movement on the facial aspect of the moving teeth caused the gingiva to have thinner buccolingual thickness.12,13 On the other hand, the buccolingual thickness of the facial gingiva increased when facially positioned teeth were moved lingually into a proper position within the alveolar envelope.4,14 The comparisons in the present study showed a significant decrease in the GTs of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth regardless of tooth movement. Contrary to animal studies, the decrease in GT in the retrusion group could be related to the changes in the width and length of the dental arch caused by orthodontic archwires.15,16 In animal studies, only the investigated teeth were subjected to orthodontic forces, and the tooth movement was performed in one direction.12–14 In the present study, the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth may have proclined during treatment and then retroclined before the conclusion of treatment.

Animal and human studies evaluating the effect of STM on KGW exhibited conflicting results. According to two previous animal studies, no significant relationship existed between STM and changes in the KGW.12,17 In one study, the maxillary and mandibular central incisors of monkeys were moved facially.12 In the other, the maxillary and mandibular central incisors of pigtail monkeys were repositioned lingually to correct a previously induced extreme labial displacement.17

Contrary to the animal studies, Dorfman18 evaluated 1150 completed orthodontic cases and concluded that the width of keratinized gingiva decreased after labial movement of mandibular incisors in 16 subjects and increased after lingual positioning of the mandibular incisors in 8 subjects. Coatoam et al.19 noted a significant decrease in the KGW of maxillary and mandibular lateral incisors and a significant increase in the KGW of the maxillary central incisor and canine teeth but provided no information about the tooth movement. The current results were more closely aligned with those of animal studies12,17 because pretreatment and posttreatment comparisons of KGW showed nonsignificant changes, except for maxillary lateral incisors in the protrusion group. As stated by Coatoam et al.,19 a decrease was determined in the KGW of the maxillary and mandibular lateral incisors, which was significant only in the maxillary lateral incisors in the protrusion group. This may have been because the lateral incisors were likely to be lingually positioned when they emerged and remained in that position if there was any crowding.20 When these teeth, which often have excessive KGW, were brought into proper alignment with orthodontic treatment, the height decreased.21 Along with this, the controversial findings between the current results and previous human studies18,19 might have been due to the measurement method. The KGW was assessed from photographic slides in those studies and, in this study, which involved direct clinical measurements, as in animal studies.

This was the first study to evaluate the correlation between cephalometric measurements and changes in the GT and KGW of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth. The findings showed that the differences in 1-NA distance, 1-NA angle, and 1-SN angle and in 1-NB distance, 1-NB angle, and IMPA angle were not significantly associated with changes in the GT of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth, respectively. In addition, a positive correlation was found between the 1-NA and 1-SN angles and the KGW of tooth number 13 and between the 1-NB distance, 1-NB angle, and IMPA angle and the KGW of tooth number 41. Only the positive correlation of KGW of tooth numbers 13 and 41 with STM may also be related to the positional changes of these teeth within the dental arch.

Previous studies also indicated an increased prevalence of gingival recession1–3 and a decreased thickness of the gingiva22 with increasing age. Although the effect of gender on gingival recession remains unclear,3,11 the GT was lower in females than in males.22 Therefore, to eliminate age-related changes in this study, the chronological age of the subjects in the protrusion and retrusion groups were matched. However, gender distribution was not controlled.

Some studies demonstrated that gingival inflammation during orthodontic treatment was significantly correlated with the development of gingival recession.1,10 Nevertheless, fixed orthodontic appliances promoted dental plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation due to the plaque's retentive effect, which makes oral hygiene more difficult.23,24 Shirozaki et al.23 observed a significant increase in PI at 6 months and 12 months after beginning orthodontic treatment and a slight increase in PD at 6 months and a decrease afterward. Liu et al.24 found a significant increase in PI and GI, with no changes in PD, after the first 3 months of orthodontic treatment and a decrease in PI, GI, and PD 6 months after removing the appliances. Yared et al.9 also reported that a minimum of 6 months after treatment was required to heal the reversible inflammation of gingival tissue via plaque control and to avoid periodontal measurement errors. Considering this information, posttreatment measurements were performed 6 months after removing the orthodontic appliances in the present study, and nonsignificant differences were determined in PI, GI, and PD, consistent with the study by Liu et al.24

The main limitations of this study included not evaluating the gingival inflammation, tooth movement, and GT during orthodontic treatment and the individual tooth movements and arch width changes after orthodontic treatment. The study had a short observation period, a small sample size, and unequal female-to-male ratios. For these reasons, a new long-term study should be conducted with a larger sample size, in which the ratio of females to males is equal, evaluations are performed during orthodontic treatment, and individual tooth movements and changes in arch width are examined after orthodontic treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

A significant decrease in the gingival thickness of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth was observed in both the protrusion and retrusion groups.

Only the keratinized gingival width of the maxillary lateral incisors exhibited a significant decrease in the protrusion group.

A positive association was determined between sagittal tooth movement and the keratinized gingival width of tooth numbers 13 and 41.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joss-Vassalli I, Grebenstein C, Topouzelis N, Sculean A, Katsaros C. Orthodontic therapy and gingival recession: a systematic review. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2010;13:127–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2010.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kassab MM, Cohen RE. The etiology and prevalence of gingival recession. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:220–225. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris JW, Campbell PM, Tadlock LP, Boley J, Buschang PH. Prevalence of gingival recession after orthodontic tooth movements. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;151:851–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wennström JL. Mucogingival considerations in orthodontic treatment. Semin Orthod. 1996;2:46–54. doi: 10.1016/s1073-8746(96)80039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evangelista K, Vasconcelos Kde F, Bumann A, Hirsch E, Nitka M, Silva MA. Dehiscence and fenestration in patients with Class I and Class IIDiv 1 malocclussion assessed with cone-beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro LO, Castro IO, de Alencar AH, Valladares-Neto J, Estrela C. Cone beam computed tomography evaluation of distance from cementoenamel junction to alveolar crest before and after nonextraction orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2016;86:543–549. doi: 10.2319/040815-235.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garlock DT, Buschang PH, Araujo EA, Behrents RG, Kim KB. Evaluation of marginal alveolar bone in the anterior mandible with pretreatment and posttreatment computed tomography in nonextraction patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2016;149:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund H, Gröndahl K, Gröndahl HG. Cone beam computed tomography evaluations of marginal alveolar bone before and after orthodontic treatment combined with premolar extractions. Eur J Oral Sci. 2012;120:201–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2012.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yared KF, Zenobio EG, Pacheco W. Periodontal status of mandibular central incisors after orthodontic proclination in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melsen B, Allais D. Factors of importance for the development of dehiscences during labial movement of mandibular incisors: a retrospective study of adult orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127:552–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djeu G, Hayes C, Zawaideh S. Correlation between mandibular central incisor proclination and gingival recession during fixed appliance therapy. Angle Orthod. 2002;72:238–245. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2002)072<0238:CBMCIP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner GG, Pearson JK, Ainamo J. Changes of the marginal periodontium as a result of labial tooth movement in monkeys. J Periodontol. 1981;52:314–320. doi: 10.1902/jop.1981.52.6.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wennström JL, Lindhe J, Sinclair F, Thilander B. Some periodontal tissue rections to orthodontic tooth movement in monkeys. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karring T, Nyman S, Thilander B, Magnusson I. Bone regeneration in orthodontically produced alveolar bone dehiscences. J Periodontal Res. 1982;17:309–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1982.tb01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raucci G, Pachêco-Pereira C, Grassia V, d'Apuzzo F, Flores-Mir C, Perillo L. Maxillary arch changes with transpalatal arch treatment followed by full fixed appliances. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:683–689. doi: 10.2319/070114-466.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming PS, Lee RT, Mcdonald T, Pandis N, Johan A. The timing of significant arch dimensional changes with fixed orthodontic appliances: data from a multicenter randomised controlled trial. J Dent. 2014;42:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelking G, Zachrisson BU. Effects of incisor repositioning on monkey periodontium after expansion through the cortical plate. Am J Orthod. 1982;82:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(82)90542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dorfman HS. Mucogingival changes resulting from mandibular incisor tooth movement. Am J Orthod. 1978;74:286–297. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(78)90204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coatoam GW, Behrents RG, Bissada NF. The width of keratinized gingiva during orthodontic treatment: its significance and impact on periodontal status. J Periodontol. 1981;52:307–313. doi: 10.1902/jop.1981.52.6.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proffit WR. The development of orthodontic problems. In: Proffit WR, HW Fields, Sarver DM, editors. Contemporary Orthodontics 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2007. pp. 72–106. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Closs LQ, Branco P, Rizzatto SD, Raveli DB, Rösing CK. Gingival margin alterations and the pre-orthodontic treatment amount of keratinized gingiva. Braz Oral Res. 2007;21:58–63. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242007000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vandana KL, Savitha B. Thickness of gingiva in association with age, gender and dental arch location. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:828–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shirozaki MU, da Silva RAB, Romano FL, et al. Clinical, microbiological, and immunological evaluation of patients in corrective orthodontic treatment. Prog Orthod. 2020;21:6. doi: 10.1186/s40510-020-00307-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H, Sun J, Dong Y, Lu H, Zhou H, Hansen BF, Song X. Periodontal health and relative quantity of subgingival Porphyromonas gingivalis during orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2011;81:609–615. doi: 10.2319/082310-352.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]