Abstract

The velvet regulators VosA and VelB are primarily involved in spore maturation and dormancy. Previous studies found that the VosA-VelB hetero-complex coordinates certain target genes that are related to fungal differentiation and conidial maturation in Aspergillus nidulans. Here, we characterized the VosA/VelB-inhibited developmental gene vidD in A. nidulans. Phenotypic analyses demonstrated that the vidD deleted mutant exhibited defect fungal growth, a reduced number of conidia, and delayed formation of sexual fruiting bodies. The deletion of vidD decreased the amount of conidial trehalose, increased the sensitivity against heat stress, and reduced the conidial viability. Moreover, the absence of vidD resulted in increased production of sterigmatocystin. Together, these results show that VidD is required for proper fungal growth, development, and sterigmatocystin production in A. nidulans.

Keywords: Velvet, VosA, VelB, asexual development, cleistothecium

1. Introduction

Aspergillus nidulans is a model organism, widely used to understand the reproduction and secondary metabolism of filamentous fungi [1,2]. Aspergillus nidulans reproduces asexually or sexually, forming developmental-specific structures during the process [3–5]. During asexual development, A. nidulans forms conidiophores, which bear asexual spores (called conidia), and the processes of conidiophore formation are tightly regulated by developmental-specific transcription factors such as BrlA, AbaA, and WetA [6]. A. nidulans also form a specialized sexual structure called cleistothecium, which contains sexual spores called ascospores. The regulatory process of fungal development is associated with secondary metabolism in fungi [7]. The results obtained in A. nidulans provide the basic knowledge for understanding other Aspergillus species such as A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. oryzae [8].

The velvet family proteins are fungus-specific transcription factors that coordinate fungal development and secondary metabolism [9]. The velvet family proteins consist of four members: VeA, VelB, VelC, and VosA in A. nidulans, containing the DNA-binding velvet domain [10]. In particular, these proteins perform different functions depending on the composition of the complex [10]. For example, the VeA-VelB-LaeA complex coordinates sterigmatocystin (ST) production and sexual development [11]. Another velvet complex, the VosA-VelB complex is a key controller for spore maturation, stress tolerance, and spore germination in A. nidulans [12,13]. Because the velvet proteins have a DNA-binding activity, research for the target genes of the VosA-VelB complex has been conducted in spores [14]. These studies primarily focused on the roles of the VosA-VelB complex in spores. Throughout transcriptome analyses, a variety of VosA and VelB target genes have been identified in A. nidulans conidia. These include spore-specific genes or developmental-specific genes with known function. Moreover, there are the VosA/VelB-activated developmental (VAD) and the VosA/VelB-inhibited developmental (VID) genes whose function is not known yet.

Several VID or VAD genes were recently characterized in A. nidulans [15,16]. The VadA (VosA/VelB-activated developmental gene) has been demonstrated to be a regulator controlling fungal development, spore viability, conidial maturation, stress tolerance, and secondary metabolism in A. nidulans conidia [16]. In addition, the VidA (VosA/VelB-inhibited developmental gene) has been shown to be a putative transcription factor, crucial for governing appropriate fungal growth, the balance between asexual and sexual development, and spore formation in A. nidulans [15]. The function of two potential vid genes, zcfA, and dnjA, were also studied [17,18]. Some direct target genes of VosA/VelB complex have been disclosed, but there are still genes that have not yet been investigated. In this study, we unveiled the characters of the gene vidD in A. nidulans.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains, media, and culture conditions

Aspergillus nidulans strains used in this study are described in Table 1. Fungal strains were grown on solid or liquid minimal media (MM) [21]. Colony photographs were taken with a Pentax MX-1 digital camera (Ricoh Imaging Company LTD, Tokyo, Japan). Photomicrographs were taken using a Zeiss Lab A1 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Jena, Germany) equipped with AxioCam 105c (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Jena, Germany) and AxioVision (Rel. 4.9) digital imaging software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Jena, Germany). Escherichia coli DH5α was grown in Luria-Bertani medium (BD, Sparks MD, USA) with ampicillin (100 μm/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO, USA) for plasmid manipulation. For auxotrophic strains, uracil/uridine (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium) or pyridoxine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO, USA) were used for cultivation.

Table 1.

Aspergillus strains used in this study.

| Strain name | Relevant genotype | References |

|---|---|---|

| FGSC4 | A. nidulans wild type | FGSCa |

| RJMP1.59 | pyrG89; pyroA4 | [19] |

| TNJ36 | pyrG89; AfupyrG+; pyroA4 | [20] |

| TYE6.1 ∼ 3 | pyrG89; pyroA4; ΔvidD::AfupyrG+ | This study |

| TYE30.1 | pyrG89; pyroA4::vidD(p)::vidD::FLAG3x::pyroAb; ΔvidD::AfupyrG+ | This study |

aFungal Genetic Stock Center; bthe 3/4 pyroA marker causes targeted integration at the pyroA locus.

2.2. Construction of the vidD deletion mutant strain

The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 2. To generate the deletion mutant strains, the double-joint PCR strategy was explored as previously described [22]. The 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of vidD were amplified from genomic DNA of A. nidulans FGSC4 using the primer pair OHS0281:OHS0283 and OHS0282:OHS0284, respectively. The A. fumigatus pyrG marker was amplified with OHS0089:OHS0090 from A. fumigatus AF293 genomic DNA. Three PCR constructs, including 5′-, 3′-flanking fragments and the AfupyrG marker, were joined, and the final cassette was amplified using the primer set OHS0285:OHS0286. The gene deletion cassette was introduced into A. nidulans RJMP1.59 protoplasts generated by the Vinoflow FCE lysing enzyme (Novozyme, Bagsvaerd, Denmark). The transformed cells were cultured in the selectable media (MM without uridine or uracil), and at least three mutants were confirmed by PCR followed by restriction enzyme digestion.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Name | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| OHS0089 | GCTGAAGTCATGATACAGGCCAAA | 5′ AfupyrG marker_F |

| OHS0090 | ATCGTCGGGAGGTATTGTCGTCAC | 3′ AfupyrG marker_R |

| OHS0281 | ATCAGACTCAGAGTGCCGTCC | 5′ vidD DF |

| OHS0282 | GCCGAAGGAGGGGTAATCAAT | 3′ vidD DR |

| OHS0283 | GGCTTTGGCCTGTATCATGACTTCA TATCGCAAGAGCATGAATATCG | 3′ vidD with AfupyrG tail |

| OHS0284 | TTTGGTGACGACAATACCTCCCGAC GCACAACCAGACAGTACCTTGG | 5′ vidD with AfupyrG tail |

| OHS0285 | ACACATCTTCGTGCCCACCT | 5′ vidD NF |

| OHS0286 | GCGCTATTTCTGGCATAGGCG | 3′ vidD NR |

| OHS0914 | aatt GCGGCCGC CTCTTCGCACACCGAGG | 5′ vidD with promoter_NotI |

| OHS0460 | aatt GCGGCCGC GGCAGTTCGCTTTCGCAG | 3′ vidD with NotI |

| OHS0449 | CCACCGAAGAGGATGCCATA | 5′ vidD RT_F |

| OHS0450 | AGATCCACTTGCCGAGAGAG | 3′ vidD RT_R |

| OHS0576 | GGTTGAAGTCGTCGGTTGAG | 5′ tpsA RT_F |

| OHS0577 | TGGAAACCGATGAGGTCACA | 3′ tpsA RT_R |

| OHS0616 | CTCCTACTCGCGTCACTTCT | 5′ orlA RT_F |

| OHS0617 | AGGAAAGACATCCACAGCCA | 3′ orlA RT_R |

aTail sequences are shown in italics. Restriction enzyme sites are in bold.

2.3. Generation of vidD complementary strain

To generate complement strains, the predicted promoter region and open reading frame of each gene were amplified using the primer pair OHS0914:OHS0460 from A. nidulans FGSC4 genomic DNA. The PCR constructs were digested with NotI and cloned to pHS13 [23]. The resulting plasmid pYE5.1 for vidD was introduced into TYE6.1 protoplast to give rise to TYE30.1. The transformed cells were cultured in the selectable MM and the complementary candidates were confirmed by PCR and quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses.

2.4. Reverse transcription- qPCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

The samples were prepared as previously described [24]. For vegetative samples, two-day grown conidia of wild type (WT) strain were incubated in liquid MM at 37 °C for 12 or 18 h. Next, the mycelia were collected, washed, squeeze-dried, and stored at −80 °C until RNA isolation. For asexual developmental samples, grown mycelia in liquid MM at 37 °C for 18 h were collected, washed, and transferred to solid MM plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C and samples were collected at the designated time points, squeeze-dried, and stored −80 °C until RNA isolation. For conidia samples, 2-day cultures of controls and mutant strains were collected and stored −80 °C.

Total RNA isolation was carried out as previously described [17]. Each sample was homogenized in 1 mL of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) using a Mini-Bead Beater (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA) and 0.3 mL of Zirconia/Silica beads (RPI, Mt. Prospect, IL, USA). The supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of iced isopropanol and centrifuged again. The RNA pellets were washed with 70% ethanol by diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) treated water and dissolved in RNase-free water. To remove genomic DNA contamination, the samples were treated with the RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and then RNA was purified using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA concentration and quality were measured by the absorbance of ultraviolet (UV) using Eppendorf BioSpectrometer, (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and qPCR was carried out using CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix. To calculate the expression levels of target genes, the 2−ΔΔCT method was used and the β-actin gene was used as the endogenous control [25,26]. Primer sets for qPCR are listed in Table 2.

2.5. Conidial trehalose analysis

The conidial trehalose assay was performed as previously described [27]. Two-day-old conidia (2 × 108) of control and mutant strains were collected, washed with ddH2O, resuspended in ddH2O, and incubated at 95 °C for 20 min. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation, transferred to a new tube, and mixed with an equal volume of 0.2 M sodium citrate (pH 5.5). The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 8 h with or without trehalase (3 mU, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), hydrolyzing trehalose to glucose. The amount of glucose generated from the trehalose was assayed with a Glucose Assay Kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.6. Conidia viability assay

Conidia viability was determined as described previously [17,27]. Fresh conidia (105 per plate) of WT and mutant strains were spread onto solid MM and incubated at 37 °C. After 2 or 10 days, the conidia were collected and counted using a hemocytometer. Approximately 100 conidia were spread onto solid MM and incubated for 2 days at 37 °C in triplicate. Survival rates were calculated as the ratio of the number of viable colonies relative to the number of spores inoculated.

2.7. Thermal tolerance assay

Thermal tolerance test was carried out as previously described [13] with minor modifications. About 1 × 103 conidia cultured for 2 days were incubated at 55 °C for 15 or 30 min. Approximately 100 conidia of control and mutant strains were spread onto solid MM. After the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h, the number of colonies was counted. The survival rates were calculated as the ratio of the number of viable colonies to the number of untreated control colonies, in triplicates.

2.8. Phenotypic analysis of cleistothecium

To examine the sexual structures, control and mutant strains were incubated on solid sexual medium (SM) at 37 °C for 7 or 21 days under dark conditions. After culture, plates were washed with 95% ethanol. Next, photographs of cleistothecia were taken using a Zeiss Lab.A1 microscope and the size of cleistothecia was measured using AxioVision (Rel. 4.9) digital imaging software.

The number of germinated ascospores in cleistothecium was recorded as previously described [28]. Control and mutant strains were inoculated onto SM for 7 or 21 days, and 10 individual cleistothecia were separated from the plates and washed with ddH2O. After being transferred to a new tube in 100 μL of ddH2O, samples were diluted three times. The diluted samples were spread into MM agar plates, incubated at 37 °C for 2 days, and then the numbers of colonies were counted. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

2.9. Sterigmatocystin extraction and thin-layer chromatography

The ST extraction was carried out as previously described [29]. Conidia (∼105) of each strain were inoculated into 5 mL of liquid complete medium and cultured at 30 °C for 7 days under dark conditions. After incubation, an equal amount of CHCl3 was added per sample. Samples were centrifuged for 10 min. The separated organic phase was transferred to new glass vials and evaporated using an oven. Samples were resuspended in 100 μL of CHCl3 and loaded into a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) silica plate with a fluorescence indicator (Kiesel gel 60, 0.25 mm; Merck, Burlington, MA, USA). The plate was developed in toluene:ethyl acetate:acetic acid (8:1:1, v/v/v), treated with 1% aluminum hydroxide hydrate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and baked at 95 °C for 1 min. TLC plate images were captured with exposure to UV (366 nm). The spot intensities of the ST were quantified using Image J software. Experiments were performed in triplicates for each strain.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between control and ΔvidD strains were evaluated by Student’s unpaired t-test. Mean ± SD are shown. P-values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. Summary of vidD

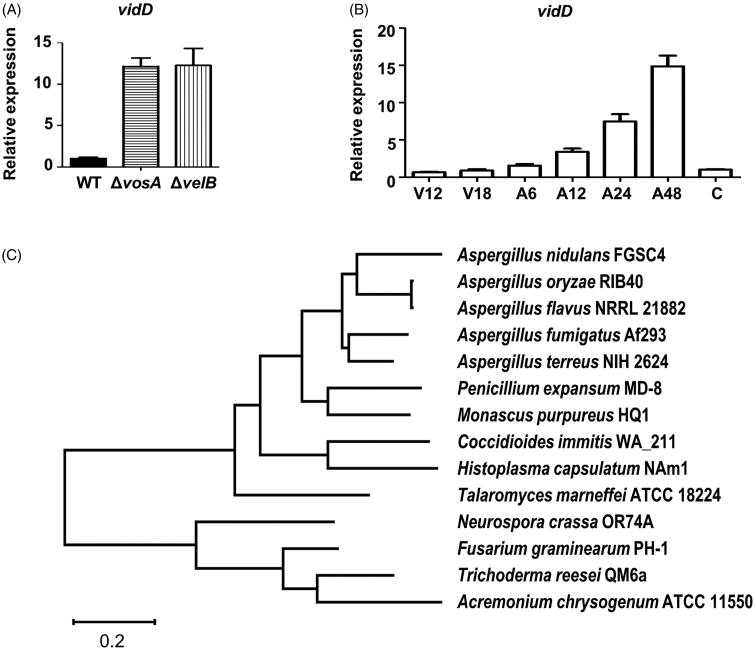

vidD (AN6859) is a putative VosA/VelB-inhibited developmental gene in A. nidulans conidia [9]. To verify whether VosA and VelB affect the expression of vidD in conidia, we checked the levels of vidD mRNA in WT, ΔvosA, and ΔvelB conidia. As shown in Figure 1(A), mRNA expression of vidD increased >10-fold in ΔvosA and ΔvelB conidia compared with WT conidia. Next, we checked the vidD mRNA level during vegetative growth and asexual development. The mRNA level of vidD was increased during post asexual developmental induction, but rapidly decreased in the conidia (Figure 1(B)). The vidD gene encodes a polypeptide consisting of 309 amino acids, but it does not contain a known domain. Next, we checked the VidD homolog in fungal systems. The VidD homolog was found in most Pezizomycotina fungi, including all Aspergillus species, but not in Saccharomycotina fungi, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans, and Basidiomycota, such as Cryptococcus neoformans and Ustilago maydis (Figure 1(C)).

Figure 1.

Summary of vidD. (A) Relative mRNA expression level of vidD was measured in wild-type (WT), ΔvosA, and ΔvelB conidia. (B) The mRNA level of vidD was measured during the life cycle of WT. V: vegetative growth, A: post asexual developmental induction, C: conidia. (C) A phylogenetic tree of VidD homolog proteins identified in ascomycetes including Aspergillus nidulans FGSC4 (XP_664463), A. terreus NIH2624 (XP_001211143), A. oryzae RIB40 (XP_023092531), A. fumigatus Af293 (XP_753347), A. flavus NRRL 21882 (RAQ43558), Talaromyces marneffei ATCC 18224 (XP_002145337), Penicillium expansum MD-8 (XP_016598290), Neurospora crassa OR74A (XP_011394950), Coccidioides immitis WA_211 (TPX23157), Histoplasma capsulatus NAm1 (XP_001543235), Fusarium graminearum PH1 (XP_011320485), Monascus purpureus HQ1 (TQB68067), Trichoderma reesei QM6a (XP_006965184), and Acremonium chrysogenum ATCC 11550 (KFH47513). A phylogenetic tree of VidD-like proteins was generated by MEGAX software (http://www.megasoftware.net/) using the alignment data from ClustalW2 and the maximum likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model. The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 1000 replicates is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analyzed.

3.2. Deletion of vidD affects fungal growth and development

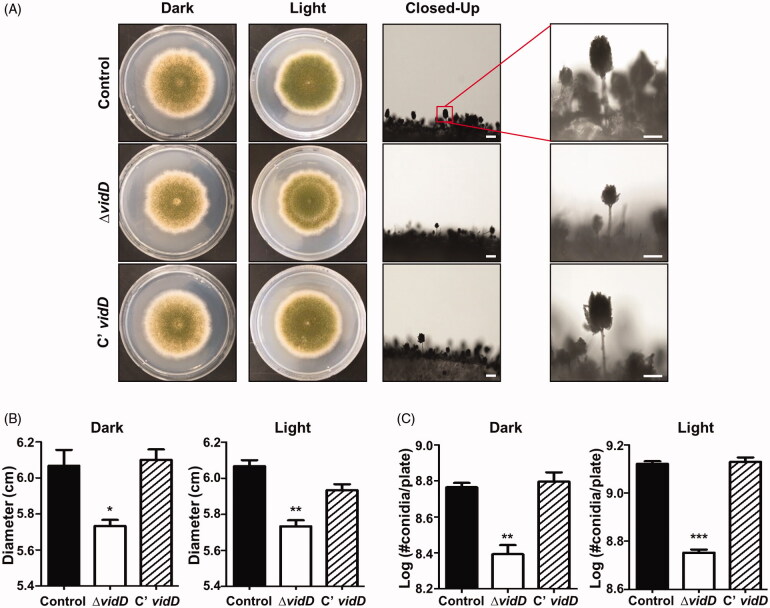

To investigate the roles of VidD, the control, vidD deletion mutant, and C’ strains were point-inoculated onto solid MM plates and incubated under dark or light conditions for 7 days. As shown in Figure 2(A), the ΔvidD null mutant produces abnormal, light green conidia compared with the control and C’ strains. The colony diameter was smaller than that of control and C’ strains (Figure 2(B)). In addition, the number of conidia produced by ΔvidD mutant was lower than that of WT and C’ strains under both dark and light conditions (Figure 2(C)). These results suggest that VidD is required for appropriate fungal growth and conidial formation in A. nidulans.

Figure 2.

Phenotypic analysis of asexual development in the ΔvidD mutant. (A) Colony photographs of control (TNJ36), ΔvidD (TYE6.1), and C’ vidD (TYE30.1) strains that were point-inoculated on solid MM plate and grown at 37 °C for 5 days under dark or light conditions. The right panel shows conidiophores of control (TNJ36), ΔvidD (TYE6.1), and C’ vidD (TYE30.1) observed under the microscope after 48 h of cultivation (bar = 0.25 μm). (B) Quantitative analysis of colony diameter for control (TNJ36), ΔvidD (TYE6.1) and C’ vidD (TYE30.1) shown in (A) (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05). (C) Quantitative analysis of asexual spore production of the strains shown in (A) (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01). All experiments were carried out in triplicates.

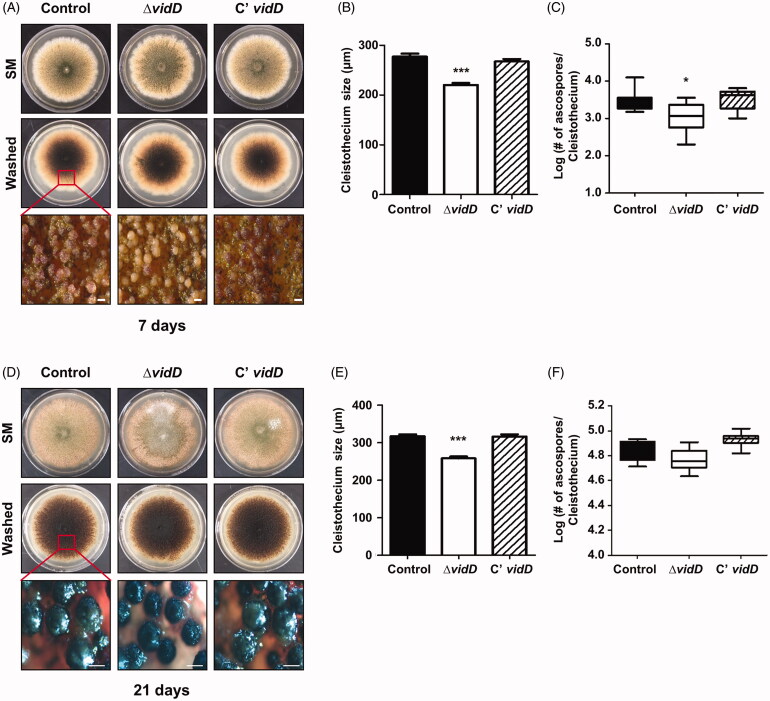

Next, we studied the function of VidD in sexual development by inoculating each strain onto SM for 7 and 21 days under dark conditions. After 7 days of cultivation, the ΔvidD mutant produced either immature cleistothecia (Figure 3(A)) or the size of the mature cleistothecia of ΔvidD were smaller than that of control and C’ strain (Figure 3(B)). In addition, the mature cleistothecium of ΔvidD contains fewer germinating ascospores compared with control and C’ strains (Figure 3(C)). At 21 days, the ΔvidD mutant produced mature cleistothecia, but these cleistothecia were smaller in size than cleistothecia of control and C’ strains (Figures 3(D,E)). The cleistothecium of the ΔvidD mutant contains an almost similar number of germinating ascospores (Figure 3(F)). Overall, these results indicated that VidD is essential for appropriate sexual development in A. nidulans.

Figure 3.

Sexual developmental phenotypes of the ΔvidD mutant. (A) Phenotypic analysis of control (TNJ36), ΔvidD (TYE6.1), and C’ vidD (TYE30.1) strains inoculated onto solid sexual media (SM) and incubated at 37 °C for 7 days under dark conditions. Bottom panel shows the cleistothecia observed by microscopy after washing off the conidia. (B) Quantitative analysis of cleistothecium size for shown in (A) (***p < 0.001). (C) Quantitative analysis of the number of germinating ascospores per cleistothecium in strains shown in (A) (*p < 0.05). (D) Phenotypic analysis of control (TNJ36), ΔvidD (TYE6.1), and C’ vidD (TYE30.1) strains inoculated onto solid SM and incubated at 37 °C for 21 days in the dark condition. Bottom panel shows the cleistothecia observed by microscope after washing off the conidia. (E) Quantitative analysis of cleistothecium size for strains shown in (D) (***p < 0.001). (F) Quantitative analysis of the number of germinating ascospores per cleistothecium in strains shown in (D).

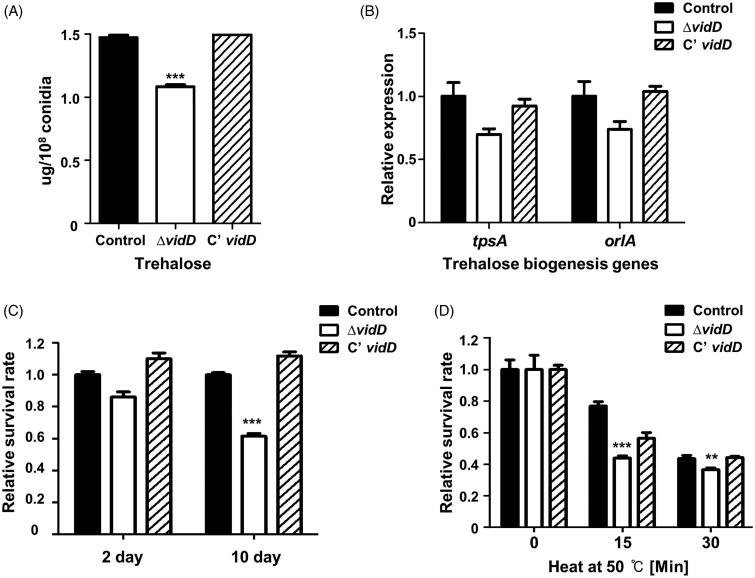

3.3. The role of VidD in conidia

The VosA/VelB complex regulates trehalose contents of conidia and spore viability in Aspergillus species [30]. To investigate whether VidD affects trehalose biosynthesis, we measured the amount of trehalose in the ΔvidD conidia. As shown in Figure 4(A), trehalose contents in the ΔvidD conidia are less than that of control and C’ vidD conidia. Next, we examined mRNA expression of the tpsA and orlA genes associated with trehalose biosynthesis. The levels of tpsA and orlA mRNA slightly decreased in ΔvidD conidia compared with control and C’ vidD conidia (Figure 4(B)), suggesting that VidD is required for proper trehalose biosynthesis.

Figure 4.

The roles of VidD in conidia. (A) The amount of trehalose per 108 conidia from 2-days cultures of control (TNJ36), ΔvidD (TYE6.1), and C’ vidD (TYE30.1) (***p < 0.001). (B) The mRNA levels of tpsA and orlA in control (TNJ36), ΔvidD (TYE6.1) and C’ vidD (TYE30.1) conidia. (C) Conidia viability for control (TNJ36), ΔvidD (TYE6.1), and C’ vidD (TYE30.1) strains grown at 37 °C for 2 and 10 days (***p < 0.001). (D) Thermal stress tolerance of conidia from control (TNJ36), ΔvidD (TYE6.1), and C’ vidD (TYE30.1) strains. About 100 conidia were incubated at 50 °C for 0, 15, and 30 min and spread into solid MM (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01).

Because trehalose is an important disaccharide for spore viability and protection against environmental stresses in fungi [31,32], we assayed conidial viability and thermal tolerance in conidia. Conidial viability of the ΔvidD mutant was decreased compared with that of control and C’ vidD strains (Figure 4(C)). In addition, ΔvidD conidia are more sensitive to thermal stress (Figure 4(D)). Together, these data demonstrated that VidD is an essential regulator of trehalose biosynthesis and thermal stress tolerance.

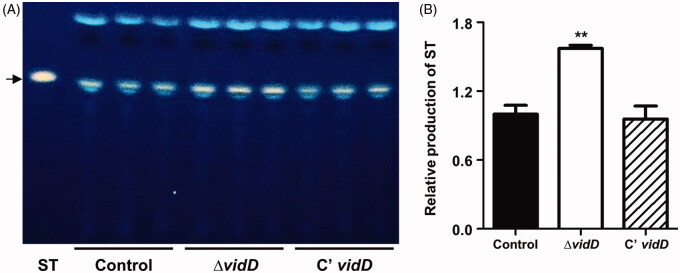

3.4. Deletion of vidD affects sterigmatocystin production

To investigate whether VidD affects sterigmatocystin production, we extracted sterigmatocystin from control, ΔvidD, and C’ vidD strains and spotted extracted samples onto TLC plates with sterigmatocystin as a standard. The absence of vidD produces a higher amount of ST compared with WT and C’ strains (Figure 5). This result implies that VidD is required for proper sterigmatocystin production.

Figure 5.

Sterigmatocystin production in the ΔvidD mutant. (A) Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate image of sterigmatocystin (ST) generated by control (TNJ36), ΔvidD (TYE6.1) and C’ vidD (TYE30.1) strains. The arrow indicates ST. (B) Relative production of ST produced after 7 days in the dark (**p < 0.01). Experiments were carried out in triplicates.

4. Discussion

The VosA-VelB hetero-complex is a key protein-complex for spore maturation, dormancy, and germination [12,23]. In addition, the VosA-VelB complex regulates transcript expression of spore-specific or developmental-specific genes in A. nidulans conidia [14]. Previously, we identified a variety of VosA (or VelB) target genes, vadA, vidA, zcfA, and dnjA in A. nidulans [15–18]. These genes are involved in asexual/sexual development, sterigmatocystin production, and conidia maturation. In this study, we characterized vidD, another VosA/VelB-inhibited developmental gene in A. nidulans. Deletion of vidD led to the formation of abnormal conidiospores and decreased conidia production. Moreover, the absence of vidD caused the delayed formation of sexual fruiting bodies and decreased germination ability of ascospores. Based on these results, we can speculate that VidD is a developmental regulator affecting both asexual and sexual development. In addition, VidD can affect the production of sterigmatocystin in A. nidulans.

Another finding is that VidD might be a potential fungal specific protein. The result of sequence similarity searching indicated that the VidD homologs were found in most Ascomycota. However, the VidD homologs could not be found in Hemiascomycota (S. cerevisiae and C. albicans), Zygomycota (Mucor circinelloides and Rhizopus oryzae), Basidiomycota (C. neoformans and U. maydis), animals, and plants. This implies that VidD can act as the fungus-specific protein in growth, development, and sterigmatocystin production. Although the cellular role of vidD was characterized in this study, the molecular role of vidD has not been studied. As a result of domain analysis, VidD does not contain a known domain, which makes it difficult to predict the molecular function of VidD. Therefore, further study will be needed to characterize the molecular role of VidD.

In conclusion, we characterized the developmental role of VidD in A. nidulans. Deletion of vidD affects colony growth, production of conidiophores, formation of sexual fruiting bodies, conidial maturation, and sterigmatocystin accumulation, implying that VidD plays multi-functional roles in A. nidulans. Additional studies will provide insight into detailed molecular mechanisms of VidD in other fungal species

Funding Statement

The work was financially supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant to HSP, funded by the Korean government [NRF-2020R1C1C1004473].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Etxebeste O, Espeso EA.. Aspergillus nidulans in the post-genomic era: a top-model filamentous fungus for the study of signaling and homeostasis mechanisms. Int Microbiol. 2020;23(1):5–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCluskey K, Baker SE.. Diverse data supports the transition of filamentous fungal model organisms into the post-genomics era. Mycology. 2017;8:67–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams TH, Wieser JK, Yu J-H.. Asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62(1):35–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyer PS, O’Gorman CM.. Sexual development and cryptic sexuality in fungi: insights from Aspergillus species. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:165–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krijgsheld P, Bleichrodt R, van Veluw GJ, et al. . Development in Aspergillus. Stud Mycol. 2013;74:1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park H-S, Yu J-H.. Genetic control of asexual sporulation in filamentous fungi. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2012a;15:669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han KH. Molecular genetics of Emericella nidulans sexual development. Mycobiology. 2009;37:171–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galagan JE, Calvo SE, Cuomo C, et al. . Sequencing of Aspergillus nidulans and comparative analysis with A. fumigatus and A. oryzae. Nature. 2005;438:1105–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed YL, Gerke J, Park HS, et al. . The velvet family of fungal regulators contains a DNA-binding domain structurally similar to NF-kappaB. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayram O, Braus GH.. Coordination of secondary metabolism and development in fungi: the velvet family of regulatory proteins. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayram O, Krappmann S, Ni M, et al. . VelB/VeA/LaeA complex coordinates light signal with fungal development and secondary metabolism. Science. 2008;320:1504–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park HS, Yu YM, Lee MK, et al. . Velvet-mediated repression of beta-glucan synthesis in Aspergillus nidulans spores. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarikaya Bayram O, Bayram O, Valerius O, et al. . LaeA control of velvet family regulatory proteins for light-dependent development and fungal cell-type specificity. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu MY, Mead ME, Lee MK, et al. . Transcriptomic, protein-DNA interaction, and metabolomic studies of VosA, VelB, and WetA in Aspergillus nidulans asexual spores. mBio. 2021;12(1):e03128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim MJ, Jung WH, Son YE, et al. . The velvet repressed vidA gene plays a key role in governing development in Aspergillus nidulans. J Microbiol. 2019;57:893–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park HS, Lee MK, Kim SC, et al. . The role of VosA/VelB-activated developmental gene vadA in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Son YE, Cho HJ, Chen W, et al. . The role of the VosA-repressed dnjA gene in development and metabolism in Aspergillus species. Curr Genet. 2020;66:621–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Son YE, Cho HJ, Lee MK, et al. . Characterizing the role of Zn cluster family transcription factor ZcfA in governing development in two Aspergillus species. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0228643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaaban MI, Bok JW, Lauer C, et al. . Suppressor mutagenesis identifies a velvet complex remediator of Aspergillus nidulans secondary metabolism. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9:1816–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon NJ, Shin KS, Yu JH.. Characterization of the developmental regulator FlbE in Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet Biol. 2010;47:981–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park H-S, Yu J-H.. Multi-copy genetic screen in Aspergillus nidulans. Methods Mol Biol. 2012b;944:183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu JH, Hamari Z, Han KH, et al. . Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 2004;41(11):973–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park H-S, Ni M, Jeong KC, et al. . The role, interaction and regulation of the velvet regulator VelB in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park HS, Nam TY, Han KH, et al. . VelC positively controls sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semighini CP, Marins M, Goldman MH, et al. . Quantitative analysis of the relative transcript levels of ABC transporter Atr genes in Aspergillus nidulans by real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:1351–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song HY, Choi D, Han DM, et al. . A novel rapid fungal promoter analysis system using the phosphopantetheinyl transferase gene, npgA, in Aspergillus nidulans. Mycobiology. 2018;46:429–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ni M, Yu J-H.. A novel regulator couples sporogenesis and trehalose biogenesis in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS One. 2007;2:e970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim MJ, Lee MK, Pham HQ, et al. . The velvet regulator VosA governs survival and secondary metabolism of sexual spores in Aspergillus nidulans. Genes. 2020;11(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Son SH, Son YE, Cho HJ, et al. . Homeobox proteins are essential for fungal differentiation and secondary metabolism in Aspergillus nidulans. Sci Rep. 2020a;10:6094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park H-S, Yu J-H.. Velvet regulators in Aspergillus spp. Microbiol Biotechnol Lett. 2016;44(4):409–419. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fillinger S, Chaveroche MK, van Dijck P, et al. . Trehalose is required for the acquisition of tolerance to a variety of stresses in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiology. 2001;147:1851–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thammahong A, Puttikamonkul S, Perfect JR, et al. . Central role of the trehalose biosynthesis pathway in the pathogenesis of human fungal infections: opportunities and challenges for therapeutic development. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2017;81(2):e00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]