Abstract

Selection of correct aminoacyl(aa)-tRNA at the ribosomal A site is fundamental to maintaining translational fidelity. Aa-tRNA selection is a multistep process facilitated by the GTPase elongation factor (EF)-Tu. EF-Tu delivers aa-tRNA to the ribosomal A site and participates in tRNA selection. The structural mechanism of how EF-Tu is involved in proofreading remains to be fully resolved. Here, we provide evidence that switch I of EF-Tu facilitates EF-Tu’s involvement during aa-tRNA selection. Using structure-based and explicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations based on recent cryo-EM reconstructions, we studied the conformational change of EF-Tu from the GTP to GDP conformation during aa-tRNA accommodation. Switch I of EF-Tu rapidly converts from an α-helix into a β-hairpin and moves to interact with the acceptor stem of the aa-tRNA. In doing so, switch I gates the movement of the aa-tRNA during accommodation through steric interactions with the acceptor stem. Pharmacological inhibition of the aa-tRNA accommodation pathway prevents the proper positioning of switch I with the aa-tRNA acceptor stem, suggesting that the observed interactions are specific for cognate aa-tRNA substrates, and thus capable of contributing to the fidelity mechanism.

Keywords: Translation, Molecular Dynamics, Energy Landscape, tRNA, Accommodation

INTRODUCTION

Translational fidelity, maintained by the ribosome, is essential to protein synthesis, the disruption of which leads to production of misfolded and potentially toxic peptides [1]. It is estimated that approximately 1 in 1,000 – 10,000 amino acids are misincorporated, resulting in ~15% of proteins containing an incorrect amino acid [2-4]. The presence of misfolded proteins is associated with many diseases including neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s [5, 6]. Additionally, antibiotics such as the aminoglycosides exert their cytotoxic effects by reducing the fidelity of the nascent polypeptide [7-9]. A complete comprehension of the mechanisms that allow the ribosome to maintain translational fidelity is therefore critical to the development of novel antibiotics and to understanding the diseases associated with translational error, protein products that are prematurely truncated, or misfolded proteins stemming from changes in translational rate [10, 11].

Several mechanisms are known to play a key role in maintaining translational fidelity such as modulating the concentration of correctly aminoacylated tRNAs and decoding of aa-tRNA at the A site [4]. Initial selection and subsequent proofreading of aa-tRNA is regulated by the universally conserved guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) Elongation Factor (EF)-Tu. EF-Tu forms a ternary complex with aa-tRNA and guanosine-triphosphate (GTP) to deliver aa-tRNA to the A site of the ribosome. The delivery of the correct (cognate) aa-tRNA is dependent upon tRNA flexibility and codon-anticodon interactions that trigger EF-Tu GTP hydrolysis [12, 13]. GTP hydrolysis and subsequent inorganic phosphate (Pi) release signals EF-Tu to undergo a conformational change [14]. This conformational change involves separation of domain I (DI) from domain II (DII) of EF-Tu and a ~90° rotation of DI with respect to DII and domain III (DIII) as EF-Tu transitions from a closed (GTP-bound) to an open (GDP-bound) conformation [15-17]. However, the extent of this conformational change during aa-tRNA selection has been recently debated. Double-labeled EF-Tu FRET studies have suggested that aa-tRNA accommodation into the ribosome can occur without, or via smaller conformational changes of EF-Tu than the canonical closed to open reconfiguration [18]. This is further supported with recent structural data of EF-Tu in the open conformation bound to GDPNP, indicating that EF-Tu has more conformational flexibility in each nucleotide bound state than previously predicted [19].

Previous molecular dynamic studies of EF-Tu have revealed several features of ternary complex dynamics and structural rearrangements during the transition from the closed to open conformation. Such reports investigate the overall dynamics and ion coordination of the ternary complex, as well as specific interactions formed during EF-Tu and aa-tRNA binding [20-22]. Universally, switch I (Gly40-Ile62) was inherently dynamic in these simulations, a finding that is consistent with structural studies [21-23]. More recently, Lai, et al. demonstrate that EF-Tu conformational change is dominated by a combined motion of domain separation and rotation, that the γ-PO4 of GTP influences switch I dynamics, and describe the dissociation of aa-tRNA from EF-Tu [24]. Yang et al. describe different pathways that EF-Tu can take during conformational change which can require disorder and that domain I of EF-Tu is likely to disengage from the ribosome first [25]. Strategies to increase EF-Tu thermostability were investigated with MD simulations by Okafor, et al. 2018, which again implicate a dynamic switch I [26]. Lastly, Warisa, et al. have demonstrated that removal of the γ-PO4 from the closed conformation increases the flexibility of switch I of EF-Tu, and that domain separation facilitates aa-tRNA dissociation [27, 28]. Taken together, these studies support a flexible switch that becomes more dynamic during EF-Tu conformational changes. Yet, the role of this increased flexibility is unclear.

To assess the role of disordered-like switch I dynamics during aa-tRNA selection, we performed a combined study of all-atom structure-based Gō like model simulations (where EF-Tu can change conformation and aa-tRNA can undergo the large conformational change from the A/T to A/A state spontaneously through thermal fluctuations) with more detailed explicit solvent simulations to describe more specific interactions of this process. Specifically, we show that switch I rapidly converts from an α-helix to a β-hairpin, facilitating Arg 58 of switch I to interact with the correctly accommodating aa-tRNA, gating the progression of aa-tRNA in the accommodation corridor. Additionally, we identify an intermediate conformation of EF-Tu (TuINT), supporting the finding of Kavaliauskas, et al., namely that EF-Tu does not have to enter into the open conformation to release aa-tRNA [18]. Pharmacological inhibition of aa-tRNA accommodation by evernimicin promotes altered interactions between Arg 58 and the aa-tRNA, indicating that changes to the accommodating tRNA are detected by switch I. These findings provide new insights into the conformational dynamics associated with EF-Tu’s delivery of aa-tRNA to the ribosome and the roles that such processes may have as part of the proofreading mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Model generation

Model complexes of 70S•EF-Tu•Phe-tRNAPhe•mRNA were derived from the Cryo-EM structures from Loveland et al. (PDB ID: 5UYK and 5UYM) [29]. These structures represent high resolution (3.2 – 3.9 Å) snap shots of an active elongation complex during accommodation. The position of the accommodated tRNA (A/A) state was constructed by aligning the 23S rRNA of a post-accommodated state (PDB ID: 4V66) with complex III from Loveland et al. 2017 (PDB ID: 5UYM) replacing the A/T aa-tRNA coordinates [29]. Both GDP and Mg2+ bound to DI of EF-Tu were added to each system by aligning EF-Tu with the crystal structures of EF-Tu•GDP complex using VMD 1.9.2 (PDB ID: 1EFC) [16, 30]. EF-Tu in the open TuGDP conformation with aa-tRNA in the A/A state was constructed by aligning and replacing EF-Tu in the closed TuGTP conformation with the crystal structure of EF-Tu in the TuGDP conformation (PDB ID: 1EFC) [16]. Evernimicin (EVN) was modeled in the A/T and A/A states through alignment of these complexes with the cryo-EM structure of the 70S with EVN bound (PDB ID: 5KCS) [31].

Each model was minimized in GROMACS v4.5.4 with AMBERFF99S force fields using the steepest descent approach [32-35]. Minimizations of the models were performed in an explicit solvent system with 100mM NaCl and a 10Å TIP3P water box for 10 000 steps. Note that, for explicit solvent MD simulations (described below), a more detailed environment was used, including a 12Å TIP3P water box with 7mM MgCl2 and 100mM KCl.

All atom structure-based simulations

Structure-based all-atom models (excluded hydrogens) were constructed from the minimized models (above) using Smog-2.1.0 [36]. All non-bonded contacts, bond distances, and angles in the accommodated state of aa-tRNA and the GDP conformation of EF-Tu were set as the native state. The potential used for the simulations is given by:

| (1) |

where,

| (2) |

and εr = 50 ε0, εθ = 40 ε0, εχi = 10ε0, εχp = 40ε0, εNC = 0.1ε0, ε0 = 1, and σNC = 2.5Å. The parameters r0, θi,0, χi,0, and φi,0 were all defined by the A/A accommodation state. Dihedrals and contact parameters were set as:

| (3) |

| (4) |

Contacts between aa-tRNA and the ribosome were scaled by 0.6 or 0.8 as these interactions are more transient than intramollecular contacts within the ribosome and to recapitulate reversable excurions of tRNA accommodation [37, 38].

Simulation protocols followed Whitford et al. at a temperature of 0.5 reduced units maintained with Langevin dynamics [38]. A total of 120 simulations were performed with Gromacs v4.5.4. Each simulation used a step size of 0.002 and had 150 million steps, for an aggregate of 18 billion time steps total sampling of the problem. Contacts and electrostatics between EF-Tu and aa-tRNA were not included in the native state, although some structure-based simulations have included them [39]. Simulations used the high-performance computing facilities at Los Alamos National Laboratory through the institutional computing program.

Explicit solvent simulations

To describe interactions between switch I and aa-tRNA in more detail than the structure-based we performed also explicit solvent simulations. All explicit solvent simulations were implemented as outlined in Girodat et al. 2019 [40]. In brief, the structures of EF-Tu in the GTP and GDP conformation (PDB ID: 1EFT and 1EFC, respectively) were used as starting templates [16, 17]. A homology model of the E. coli EF-Tu in the GTP conformation was generated using the SWISS-MODEL server [41-44]. Starting conformations of EF-Tu for explicit solvent simulations were taken at approximately 2Å intervals of Rswi-DIII (see below) as intermediates of switch I. All models were solvated with a 12Å TIP3P water box with 7mM MgCl2 and 100mM KCl using the solvate and autoionize packages in VMD [30]. Each system was minimized using the steepest descent approach, minimizing all water then all non-water atoms for 10,000 steps twice followed by a 100,000 step minimization of the entire system. The models were equilibrated to 300 and 350 K using NAMD and CHARMM 36 parameters [45, 46]. Each simulation was performed with a timestep of 2 fs for 25 ns using the velocities and coordinates from the 300 and 350 K equilibrations, respectively, with an aggregate sampling of 275 ns. Temperature and pressure were maintained with Langevin dynamics and Langevin piston, respectively.

Reaction coordinate definition

The reaction coordinate Relbow, used to measure aa-tRNA accommodation, defined as the distance between the O3’ atoms of U8 in the P-site tRNA and U60 in the A-site tRNA as previously described by Noel et al. [47] (see ‘Results’ for a discussion of choice of reaction coordinates). The separation of domain I and II of EF-Tu was measured by Rdom which is the reaction coordinate for the distance of Gly40 and Phe261 of EF-Tu. We also measured the distance of Arg58 of switch I to Ala375 of domain III of EF-Tu (RswI-DIII) and to the CCA end of the A site aa-tRNA (RswI-CCA). Reaction coordinates were fit with a one exponential function (eq 5) to determine the apparent rate for their completion.

| (5) |

Where y0 is the reaction coordinate at frame 0, A is the amplitude of the reaction coordinate, and kapp is the apparent rate.

Approximation of Boltzmann weighted Free-energy landscapes

Energy landscapes over the reaction coordinates were determined using the g_sham package in GROMACS v4.5.4 using the equation:

| (6) |

Where, ΔG* is the approximated free energy of the landscape, kB is the Boltzmann coefficient, T is the temperature (300°K), P(xi) is the probability of being at state i, and Pmax(x) is the maximum probability of the most observed state. Here, ΔG* approaches the actual free energy landscape if sufficient sampling is obtained (see below for convergence definition). All free-energy landscape approximations are derived from an accumulation of 60 simulations, aggregating both 0.6 and 0.8 scaling of aa-tRNA and ribosome contacts. Quality and completeness of the simulations were determined by calculating the convergence of the Boltzmann weighted free-energy approximations.

Convergence of simulations

Convergence of the simulations was measured as described in Vaiana and Sanbonmatsu 2009 [48]. The time dependence of the average deviations σ(t) of the Boltzmann weighted landscape over Relbow and Rdom using the equation:

| (7) |

Where, ΔG(i,j)t is the Boltzmann weighted landscape of Relbow and Rdom at time t and ΔG(i,j)t0 is the Boltzmann weighted landscape of Relbow and Rdom at time 0, and N is the number of grid points on the free energy landscape.

RESULTS

Reaction coordinates that describe switch I dynamics

To assess switch I flexibility during accommodation of aa-tRNA we performed non-equilibrium structure-based model simulations starting from a pre-A/T tRNA (no codon-anticodon interactions) and a closed EF-Tu configuration (TuGTP) ending in an A/A tRNA and open EF-Tu configuration (TuGDP) (Fig. 1A). Simulations of this type are excellent at determining the sterics of transitions and geometric effects occurring during rearrangements of large biomolecular systems ( >100 000 atoms) and have often been used to study tRNA dynamics within the ribosome, co-translational folding, and protein conformational changes [25, 38, 47, 49-58]. While the method contains electrostatic effects in so as much as they are required for the native state, the method does not explicitly include these effects during transitions. To fill in the gaps of our results we supplemented our analysis with explicit solvent simulations to resolve specific interactions that could not be identified by a structure-based approach alone.

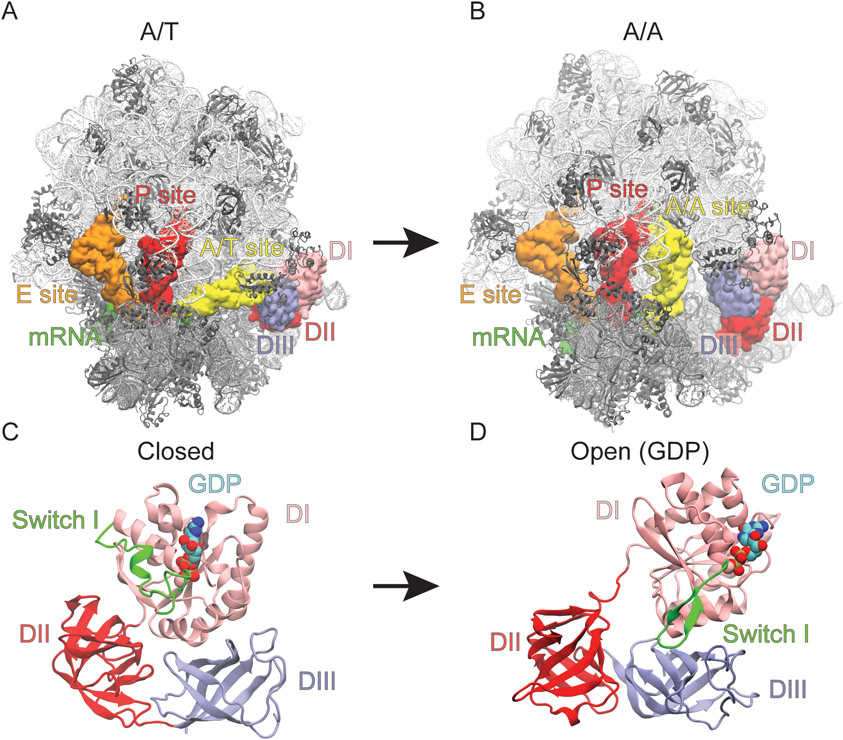

Figure 1. Conformational rearrangement of EF-Tu and the ribosome during aa-tRNA accommodation.

Structural representations with ribosome in white and grey, A, P, and E site tRNA in yellow, red, and orange respectively, mRNA in green, and EF-Tu in pink, red and blue. (A) The A/T and (B) A/A conformation of the ribosome with EF-Tu in the closed and open conformation, respectively representing the beginning and final (native) state of the structure-based simulations. The conformational rearrangement of EF-Tu in the (C) closed (GTP-bound) and (D) open (GDP-bound) conformations. Switch I of EF-Tu highlighted in green as it transitions from the α-helix to β-hairpin.

In our structure-based simulations the shoulder of the 30S moved ~4-5Å towards the 30S body consistent with domain closure identified by X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM studies [29, 59, 60]. The observed 30S domain closure leads to docking of EF-Tu onto the Sarcin Ricin loop (SRL) (residues C2652-G2668 of the 23S rRNA). Codon-anticodon interactions between the mRNA and aa-tRNA rapidly formed after docking onto the SRL. No conformational changes in EF-Tu were observed until after codon-anticodon interactions had occurred, consistent with cryo-EM and smFRET data [18, 29]. In these simulations, EF-Tu is able to undergo conformational rearrangement and the aa-tRNA is able to accommodate into the A site via thermal fluctuations. The restrictions on these movements are imposed by sterics and the non-bonded contacts native to the A/A conformation of the ribosome and aa-tRNA or the open conformation of EF-Tu (Figs. 1A, B). The simulations converged at ~ 100 x 106 time steps, in terms of aa-tRNA accommodation and EF-Tu rearrangement, as determined by measuring the deviation in the Boltzmann weighted free energy landscapes of reaction coordinates Rdom and Relbow, described below (Fig. 3A; Fig. S2).

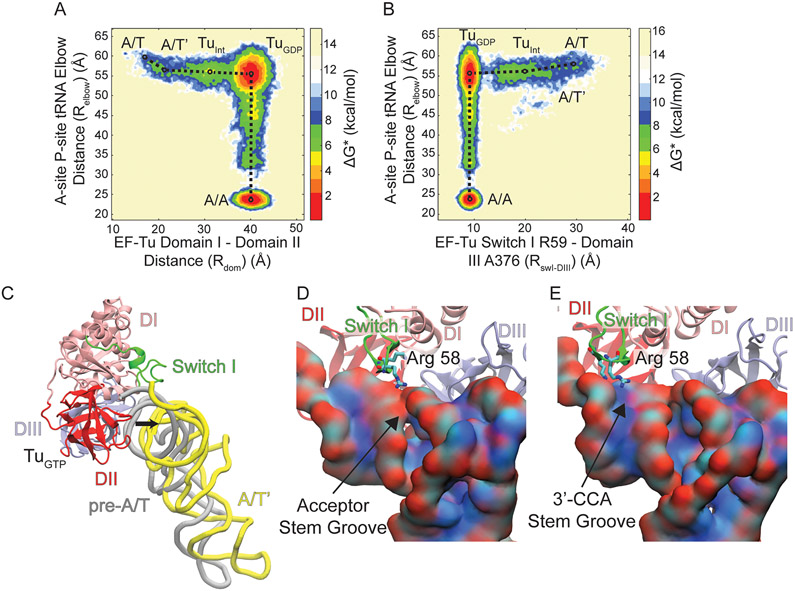

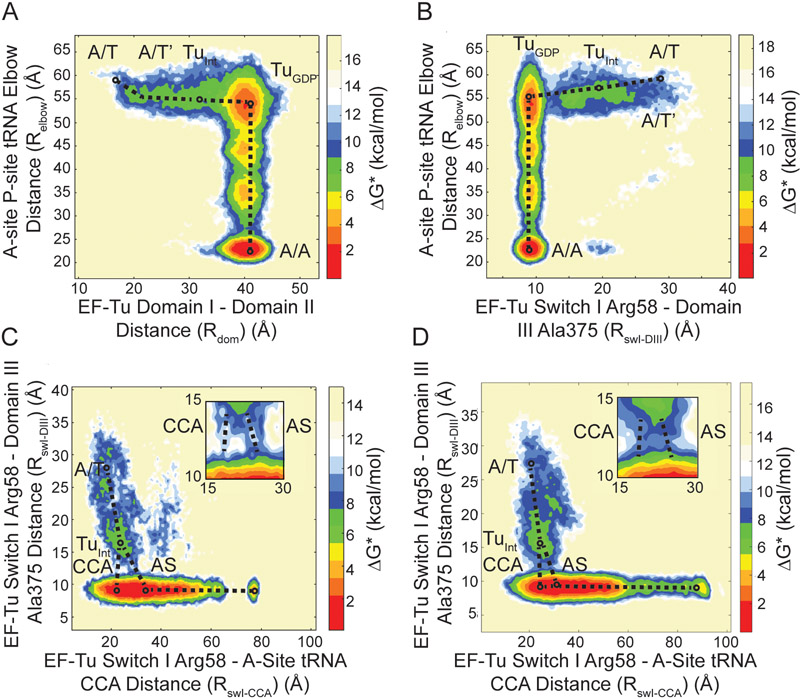

Figure 3. Conformational rearrangement of switch I during aa-tRNA accommodation.

Boltzmann weighted approximate free energy landscapes determined from position occupation probabilities. (A) Aa-tRNA accommodation measured by Relbow with respect to EF-Tu domain separation measured by Rdom. The landscape reveals that EF-Tu domains separate from 16Å to 40Å before aa-tRNA accommodates. However, there is an initial movement of the aa-tRNA from ~60Å to ~55Å, labeled A/T’. During domain separation a population is observed before entering the TuGDP conformation labelled TuINT. (B) Aa-tRNA accommodation (Relbow) with respect to EF-Tu switch I dynamics measured by RswI-DIII). The movements of switch I from the A/T state (30Å) to TuGDP (10Å) occur before aa-tRNA accommodation. The initial movement of aa-tRNA can be observed (A/T’) and the intermediate population (TuINT) is resolved by RswI-DIII as well. (C) Structural representation the pre-A/T (gray) and A/T’ (yellow) position of aa-tRNA after a 5Å movement away from EF-Tu. Switch I is represented in green in the TuGTP conformation. (D) Representation of Arg 58 of EF-Tu which traverses the (D) major acceptor stem groove or (E) the 3’-CCA end minor groove of the aa-tRNA, which is colored by atom to highlight the PO4 containing negatively charged backbone.

To properly describe the dynamics of EF-Tu during aa-tRNA accommodation we selected several reaction coordinates. The reaction coordinate Relbow defined by Noel et al. 2014 was used to define aa-tRNA accommodation as it meets the criteria of an efficient reaction coordinates defined by Best et al. 2005 (Fig. S1A) [47, 61]. This reaction coordinate reveals the barriers of aa-tRNA accommodation imposed by rRNA helix 89. The movements of switch I relative to EF-Tu and aa-tRNA were measured by the reaction coordinates RswI-DIII (distance from Arg58 of switch I to A375 of domain III) and Rswi-CCA (distance from Arg58 of switch I to the CCA end of the aa-tRNA), respectively (Figs. S1C, D). Two unique reaction coordinates were chosen to describe the movement of switch I with the respect to the barrier created by interactions of switch I with aa-tRNA during EF-Tu conformational change (Rswi-DIII), and to resolve this barrier in terms of position relative to the aa-tRNA (Rswi-CCA). To describe the domain separation associated with the transition of EF-Tu from the closed to open conformation (labelled TuGTP and TuGDP as these are the classical GTP and GDP conformations) we measured the distance between G40 in domain I and F261 in domain III (Rdom) (Fig. S1B). Each of these reaction coordinates span over 20Å and capture transition states during EF-Tu conformational change and aa-tRNA accommodation.

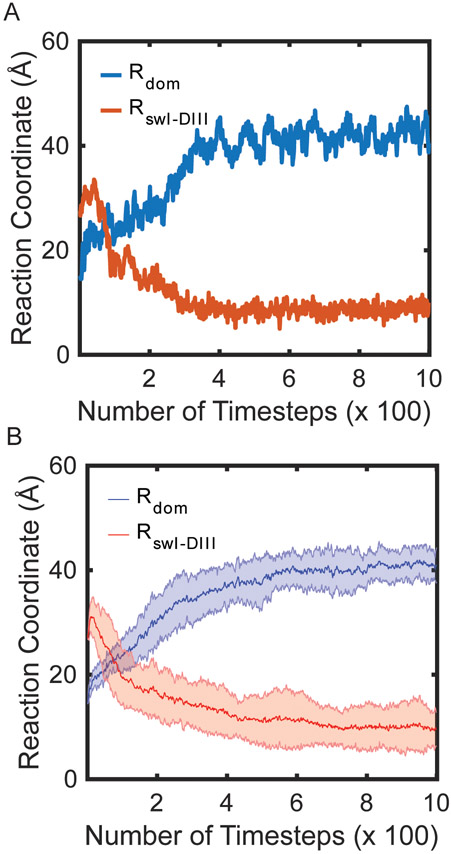

EF-Tu domain rearrangement follows switch I movements

Consistent with Warias et al., the initial conformational change in EF-Tu is within switch I; however, we observe rapid conformational change of switch I from an α-helix (residues Ala52-Gly59) to a β-hairpin (resides Pro53-Thr61) (Video 1) [28]. The conversion of switch I to a β-hairpin is quickly followed by the movement of switch I along the reaction coordinate RswI-DIII (Fig. S3). Switch I approaches the major groove of the acceptor stem (nucleotides C2-G6 and C61-U66) of the aa-tRNA closest to the A site, leading to interactions between switch I and the acceptor stem (Fig. S3). The movements of switch I are coupled with the domain separation (Rdom) within EF-Tu (Figs. 2 A, B). A single-exponential function was fit to each reaction coordinate to calculate an apparent rate (kapp) of the processes observed and to determine the order of events during this conformational change. Rswi-CCA is ~2.25 fold faster than Rdom in our simulations with an apparent rate of 9 x 10−2 timestep−1 compared to 4 x 10−2 timestep−1. Although this is not a precise physical timescale, the events/timestep help resolve the order of events. To ensure that this order is not an artifact of the strength of the contacts in the native state, the weight of the contacts unique to the A/A state were reweighted to 0.6, 0.8, or 1 (Figs S4 A, B; Table S1). Regardless of the weight of the native contact basin, the order of switch I movements preceding EF-Tu domain rearrangement was maintained. As the final position of switch I is packed against DIII of EF-Tu, we infer that these interactions are required before domain separation can complete.

Figure 2. EF-Tu conformational rearrangement of switch I precedes domain separation.

(A) Single MD simulation of EF-Tu domain separation and switch I movements measured with the reaction coordinates Rdom and RswI-DIII (scaled by 0.8). (B) Average and standard deviation of the reaction coordinates Rdom and RswI-DIII of 20 individual simulations (scaled by 0.8). The average traces were fit with Eqn. 5 to determine kapp.

Switch I directly interacts with the acceptor stem of aa-tRNA after GTP hydrolysis

To probe transition states during switch I movement and interactions with aa-tRNA acceptor stem, we utilized approximate Boltzmann weight free energy landscapes, where the probability density of two reaction coordinates can be compared. If both reaction coordinates are sufficiently sampled, the landscape represents the free energy landscape. In molecular simulations generally, it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine if the system has fully achieved equilibrium: if one performs a full explicit solvent MD simulation of 100 ms or even 1 s in order to achieve equilibrium, one could always imagine a 10s or 100s simulation that could potentially disprove this claim. Thus, we use the notation ΔG* to indicate that the calculation may not reflect the true free energy landscape, but rather an approximate free energy landscape, characterized by a convergence criterion (see Eqn. 7), that approaches the true free energy landscape upon exhaustive sampling.

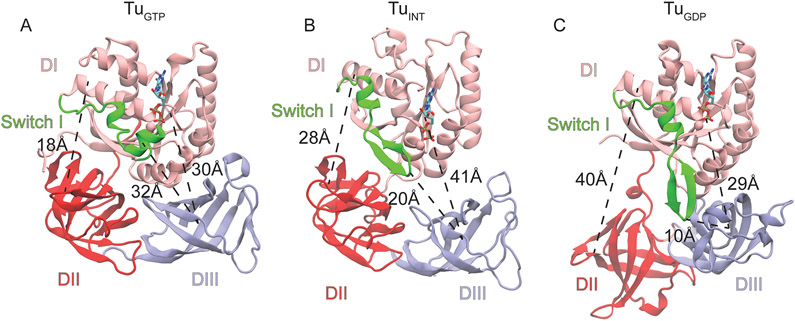

To identify barriers associated with switch I movements which precede domain separation, we utilized these Boltzmann weighted free-energy approximations. The aforementioned initial switch I movement leads to an observed intermediate position (TuINT) when Relbow is compared with RswI-DIII on the landscape (Fig. 3A). In this intermediate conformation, switch I is more proximal to DII than DIII (Fig. 4B). The TuINT conformations are also resolved by domain separation (Rdom) relative to Relbow, indicating that in this position, TuINT has semi-separated domains alongside the switch I positioning (Figs. 3B, 4B). The TuINT conformation is defined by an increased 10Å and 11Å distance between DI-DII and DI-DIII, respectively, compared to TuGTP, yet has a 12 Å decreased DI-DII and 12 Å increased DI-DIII separation compared to TuGDP (Figs. 3A, B, C). This conformation is biochemically supported by Kavaliauskas, et al., which suggests that EF-Tu does not undergo the full conformational change to the TuGDP conformation on the ribosome [18]. The 0.06 FRET efficiency change observed from Kavaliauskas et al., with Cy-3 and Cy-5 labels corresponds to a distance change of ~2 Å (determined from a Förster radius of 53 Å). Although DI and DIII are 11Å apart between TuGTP and TuINT, without domain rotation the fluorophore positions (T33 and M351) are only ~2 Å apart. This supports a model where EF-Tu enters into the TuINT conformation on the ribosome, which is sufficient for aa-tRNA release. After TuINT, EF-Tu can then transition into the TuGDP conformation before the aa-tRNA accommodates into the A site (Fig. 3C). The observations that both switch I movements and domain separation stall at TuINT suggest the presence of a barrier along EF-Tu conformational rearrangement.

Figure 4. Conformations of EF-Tu during aa-tRNA accommodation.

(A) The classical closed conformation of EF-Tu bound to GDPNP (PDB ID: 1EFT) with a DI-DII distance of 18Å, DI-DIII distance of 30Å, and a switch I-DIII distance of 32Å. (B) The intermediate conformation of EF-Tu resolved by structure based simulations where the DI-DII and DI-DIII distances have increased to 28 and 41 Å, respectively and switch one is in an intermediate proximity to DIII at a distance of 20Å. (C) The classical open conformation of EF-Tu bound to GDP (PDB 1EFC). DI-DII is fully open at a distance of 40Å, DI has approached DIII and switch I is packing with DIII.

To investigate what steric interactions are producing the barrier preventing uninterrupted EF-Tu conformational change, we measured the position of aa-tRNA relative to switch I. Before EF-Tu enters the TuINT conformation, the aa-tRNA undergoes a 5 Å movement to reaching a meta-stable position (A/T’) (Figs. 3A, B, C). The aa-tRNA maintains the A/T’ position until EF-Tu has adopted the TuGDP conformation and switch I interacts with DIII (Figs. 3A, B). The dependence of aa-tRNA movement on the position of switch I suggests that this motif is limiting or ‘gating’ aa-tRNA accommodation. Once EF-Tu has undergone the conformational change into the TuGDP conformation the aa-tRNA can accommodate. This transition, however, is relatively slow due to a high probability of the aa-tRNA remaining in the A/T’ position (Figs. 3A, B). When the aa-tRNA proceeds to the A/A state, the largest energy barrier it encounters is at an Relbow value of ~30Å. This barrier is imposed by rRNA helix 89 of the ribosome, consistent with previous reports [38, 47, 54, 62]. Ultimately, the free energy landscape approximations reveal that the A/T’ position of aa-tRNA is coupled with TuINT positioning of switch I and domain separation.

The A/T’ position of aa-tRNA is supported by smFRET studies from Geggier et al., where labelled A and P site tRNA are used to identify aa-tRNA accommodation dynamics [37]. In the presence of a non-hydrolysable analogue of GTP (GDPNP) or kirromycin, fluctuations from the GTPase activated (A/T) state into an intermediate FRET state prior to accommodation are observed [37]. These fluctuations are consistent with the A/T’ aa-tRNA position. Both GDPNP and kirromycin limit the conformational change of EF-Tu, likely preventing rearrangement of switch I from an α-helix to β-hairpin. This suggests that aa-tRNA can enter into the A/T’ position with limited EF-Tu conformational change; however, the aa-tRNA cannot proceed to accommodation until EF-Tu has undergone a more substantial conformational rearrangement.

Switch I traverses the tRNA acceptor arm between TuGTP and TuINT

Our MD simulations indicate that the A/T’ aa-tRNA position is directly interacting with switch I, suggesting that these interactions proved the barrier for EF-Tu conformational change (Video 1). Between TuGTP and TuINT, switch I has to traverse the tRNA acceptor arm from the A site side of the A/T tRNA distal from EF-Tu to pack against DIII (Fig. 3C; Fig. S3). For switch I to reach its position in TuINT , the aa-tRNA has to cross the steric barrier switch I creates at the A site side of A/T tRNA. To cross the barrier imposed by switch I, the major groove of the aa-tRNA acceptor stem composed of nucleotides C2-G6 and C61-U66 must align with switch I (Fig. 3D). Switch I can also interact with the minor groove near the 3’-CCA end of the aa-tRNA (nucleotides G1 to G5 and G70 to G74), although this position occurs less frequently (Fig. 3E, Fig 5C). The amino acids of switch I that interacts with the acceptor stem groove of the tRNA during these motions are Arg58 or Lys 56. These positions are conserved as positively charged amino acids, enabling interactions with the negatively charged phosphate backbone groove of the tRNA (Fig. 3D, E) [63].

Figure 5. Effect of the antibiotic Evernimicin (EVN): pathway of switch I of EF-Tu as it passes through the grooves of aa-tRNA.

(A) Accommodation pathway of aa-tRNA (Relbow) with respect to domain separation of EF-Tu (Rdom) in the presence of EVN, revealing the presence of the A/T’ movement and occupation of the TuINT conformation. (B) Movement of switch I (RswI-DIII) with respect to aa-tRNA accommodation (Relbow) in the presence of EVN, revealing a pathway including the A/T’ movement of aa-tRNA and the TuINT conformation. The pathway of switch I during domain separation resolved by RswI-CCA and RswI-DII. RswI-CCA is the distance between switch I Arg58 and the 3’-CCA end of the aa-tRNA. A bottleneck for conformational change of EF-Tu is observed at RswI-DIII ~12Å and RswI-CCA ~24Å, this corresponds to the position where switch I is interacting with aa-tRNA. Free energy landscape approximations reveal that (C) In the absence of antibiotics aa-tRNA accommodates with switch I positioned in the acceptor stem groove predominately over the 3’-CCA end groove (CCA) and (D) in the presence of EVN switch I is more likely to be positioned in the 3’-CCA end groove. Inserts in the top right of the landscape approximations highlight the transition barrier imposed by steric interactions between EF-Tu and aa-tRNA.

The aa-tRNA switch I interactions represent a stable intermediate

The landscapes in Fig 3 suggest a meta-stable (TuINT) conformation of EF-Tu prior to aa-tRNA accommodation. To ascertain what interactions are being formed between EF-Tu and the aa-tRNA in TuINT , we performed 11 short (25ns) explicit solvent simulations starting from structural snapshots of EF-Tu at ~2 Å intervals along the RswI-DIII reaction coordinate (Fig. S3), for a total of 275 ns aggregate sampling. Explicit solvent simulations were used to characterize in more detail hydrogen bonds that could form between the negatively charged aa-tRNA backbone and the positively charged Arg58 and Lys 56 of switch I. Our simulations reveal that Lys 56 makes more hydrogen bonds early on in RswI-DIII (at RswI-DIII = 15 Å) forming ~10-15% more hydrogen bonds than either hydrogen bond donors from the amides of the guanidinium moiety from Arg 58 (Table 1). These hydrogen bonds are not specific to a particular phosphate of the aa-tRNA and occur at the ribosome-side of the acceptor stem groove. As the RswI-DIII distance increases Lys 56 loses interactions with the aa-tRNA while Arg 58 makes hydrogen bonds with the acceptor stem groove up to 68% of simulation time (Table 1). We do not observe Arg 58 or Lys 56 forming interactions with specific nucleotides of the aa-tRNA. We do, however, observe both amino acids making transient interactions with the phosphates of the acceptor stem groove. These transient interactions allow Arg 58 and Lys 56 to engage with the acceptor stem groove, yet still permit switch I to cross the aa-tRNA acceptor stem groove. As Arg 58 loses interactions with the aa-tRNA, we observe Lys 56 again forming hydrogen bonds with the aa-tRNA (at RswI-DIII = 25 Å) (Table 1). Because Lys 56 only forms hydrogen bonds before and after Arg 58 engages with the aa-tRNA, interactions between Lys 56 and the aa-tRNA may be required to properly position switch I as Arg 58 begins to transition through the acceptor stem groove of aa-tRNA.

Table 1. Percentage of simulation time that Arg58 or Lys56 are involved in hydrogen bonds with the backbone of aa-tRNA, determined from short time scale explicit solvent simulations.

Hydrogen bond donors and acceptors have to be within 3.0Å and form a 40° angle between the donor-H-acceptor atoms. Eleven simulations were performed for 25ns at intervals along the RswI-DIII reaction coordinate to measure stability of switch I aa-tRNA interactions, for an aggregate sampling of 275 ns. Arg 58 has two potential hydrogen bonding nitrogens on the guanidinium group.

| RswI-DIII (Å) | % of frames side chain nitrogen is hydrogen bonded to aa-tRNA backbone |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Arg 58 (NH2 1) | Arg 58 (NH2 2) | Lys 56 (NH3) | |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 28 | 22 | 37 |

| 18 | 68 | 56 | 3 |

| 20 | 22 | 22 | 3 |

| 22 | 29 | 20 | 2 |

| 23 | 3 | 55 | 10 |

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| 27 | 11 | 23 | 0 |

| 29 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Interestingly, in these simulations, switch I is as flexible as it is in the TuGTP or TuGDP conformations (Fig. S5). This indicates that the pathway that switch I proceeds on through RswI-DIII reduces the dynamics of switch I compared to immediately following GTP hydrolysis. The low RMSF of switch I as it passes across the aa-tRNA indicates that the path switch I takes is relatively ordered due to the restrictions of the phosphates in the acceptor stem groove (Fig. S5). The loss of dynamics of switch I may contribute to the barrier for aa-tRNA crossing of switch I as the system could have a net decrease in entropy. This suggests that the coordination of switch I is functionally required during aa-tRNA accommodation. If switch I-aa-tRNA crossing were not required, then it would be likely that switch I remains disordered to promote aa-tRNA accommodation as an entropically favored process.

Delay of aa-tRNA accommodation promotes an alternate switch I path

To test our hypothesis that aa-tRNA needs to pass over the switch I barrier for EF-Tu mediated accommodation, we performed simulations of accommodation in the presence of the antibiotic evernimicin (EVN). EVN binds to rRNA helix 89 of the large subunit, the RNA helix that has been shown to be a steric barrier during aa-tRNA accommodation [38, 47, 54, 62]. Structural and smFRET studies suggest that EVN reduces the rate of aa-tRNA accommodation likely by increasing the energy required for aa-tRNA to cross the helix 89 barrier [31]. Therefore, we can use this antibiotic to reduce the rate of aa-tRNA accommodation in our simulations and investigate the altered behavior of aa-tRNA relative to switch I. The overall landscapes for switch I movements (Rswi-DIII) and domain separation (Rdom) relative to aa-tRNA accommodation (Relbow) are similar in the presence and absence of EVN (Figs. 2A, B; Figs. 5A, B). In the A/T’ position of aa-tRNA C17 of the elbow interacts with EVN (Fig. S6). This interaction influences the angle of the aa-tRNA, with respect to the mRNA, in the accommodation corridor (Figs. S7 A, B). As a result, switch I is coordinated to the 3’-CCA groove more frequently with EVN than in the absence of antibiotic. This is consistent with the Boltzmann weighted approximate free energy landscape of RswI-CCA compared to RswI-DIII, describing the position of switch I with respect to the aa-tRNA. The barrier for aa-tRNA moving past switch I can be observed at an RswI-DIII value of 13Å and RswI-CCA of 28Å, describing switch I passing through the acceptor stem groove of the tRNA in the absence of EVN (Fig. 5C). In the presence of EVN, the 3’-CCA groove pathway becomes more prominent at an RswI-DIII of 13Å and an RswI-CCA of 24Å (Fig. 5D). Altogether, this indicates that alteration of aa-tRNA accommodation leads to a non-canonical pathway of aa-tRNA with respect to switch I.

DISCUSSION

EF-Tu has evolved a β-hairpin in switch I to interact with aa-tRNA

Previously, it has been shown that switch I of EF-Tu likely contributes to the stability of the GDP conformation [40]. The simulation data provided here indicate that it also has a functional role in aa-tRNA accommodation. The role of switch I in accommodation of cognate aa-tRNA is likely the reason that EF-Tu is the only translational GTPase with a β-hairpin switch I. For most translational GTPases such as release factor (RF) 3, EF-G, initiation factor (IF)-2,[64] LepA (EF-4), and BipA, switch I is not resolved in structural studies, or only resolved as a loop [65-69]. The indication that switch I (residues Phe46-Ile62) of EF-Tu is critical to the protein’s function is the fact that switch I is 82% conserved where Arg58 is 98% conserved, only occurring as a Lys other than Arg [63]. Since only positively charged amino acids occur at position 58, it is likely that interactions with this region and a negatively charged surface, such as the backbone of aa-tRNA, are required for EF-Tu’s function. Besides Arg58, switch I contains Lys56, another positively charged amino acid, which is Lys 66% or Arg 32% of the time. It is likely that these two positions are conserved to interact with the aa-tRNA.

Besides EF-Tu, selenocysteine specific factor (Sel) B is specifically responsible for delivery of selenocysteine-tRNA to the ribosomal A-site in a SECIS element dependent manner [70]. If a structured switch I is required for aa-tRNA delivery then SelB would be expected to have a β-hairpin switch I in the GDP conformation. However, the only resolved structure of SelB bound to GDP reports the protein in the closed configuration with an unresolved switch I [71]. Nonetheless, the “open” (or TuGDP equivalent) configuration of SelB has yet to be resolved. Structural alignment of EF-Tu with SelB indicates that an Arg in switch I is structurally conserved in EF-Tu and SelB (Fig. S7) [72]. While a corresponding Arg is also present in E. coli EF-G, RF3, and LepA, these proteins do not have the flanking positively charged Lys residues that are present in EF-Tu and SelB (Fig S7) [73]. Interestingly, a switch I Arg residue is lacking in E. coli IF-2, EngA, and YchF [74], suggesting that the switch I Arg may be a specific feature of elongation and termination factors.

Model of EF-Tu dissociation from aa-tRNA and ribosome

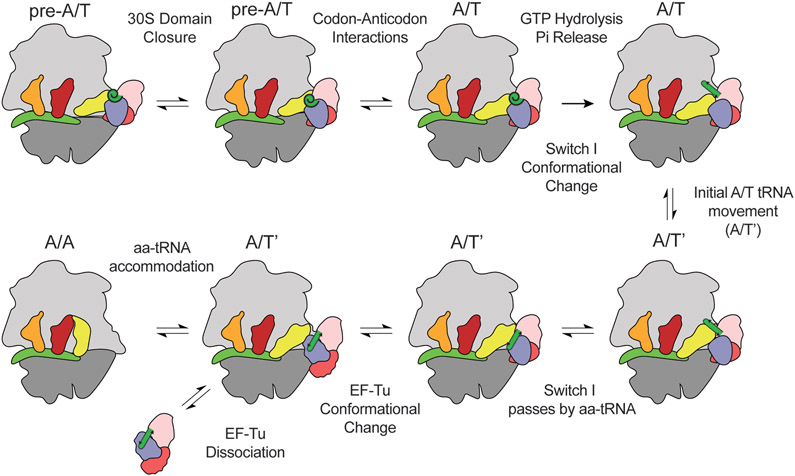

Overall our data supports a model where EF-Tu can detect the position of the aa-tRNA in the accommodation corridor based on the position of switch I. The delivery of aa-tRNA to the A site would then follow the process of ternary complex binding to the 30S, domain closure docking EF-Tu onto the SRL, followed by codon-anticodon interactions. Once this state is achieved, EF-Tu enters the GTPase-activated state, where EF-Tu rapidly hydrolyzes GTP. Pi is then released from EF-Tu triggering the conformational rearrangement of EF-Tu. EF-Tu does not enter the open configuration but the TuINT conformation, where switch I adopts a β-hairpin. In the TuINT conformation, the aa-tRNA undergoes an initial ~5Å movement away from EF-Tu, consistent with smFRET data, an excellent approach to resolve ribosome dynamics [37, 75-77]. The movement of aa-tRNA is gated by switch I, which interacts with the acceptor stem of the A site side of the tRNA. Gating aa-tRNA movements during accommodation has been proposed before, as L3 gates movement of aa-tRNA into the peptidyl transferase center [78]. It is not until switch I is coordinated to the acceptor stem groove that the aa-tRNA can pass by switch I to enter into the A site (Fig 6). This, in turn, allows switch I to pass through the aa-tRNA, reach the rest of EF-Tu, and pack against DIII, which likely leads to EF-Tu’s conformational change and dissociation from the ribosome.

Figure 6. Model of switch I involvement in aa-tRNA accommodation.

After ternary complex binds to the 30S subunit, the 30S domain closes at the A-site to dock EF-Tu onto the SRL and 50S. Codon-anticodon interactions are then formed completing the GTPase activated state. Once in the GTPase activated state GTP is hydrolyzed, Pi release, allowing switch I to undergo a conformational change from an α-helix to a β-hairpin. This initial rearrangement of EF-Tu allows aa-tRNA to undergo an initial ~5Å movement (A/T’). After the A/T’ movement switch I interacts with the acceptor stem of the aa-tRNA. Switch I has to pass by the aa-tRNA to allow for accommodation. Stalling in aa-tRNA accommodation prevents switch I from passing by the aa-tRNA. Once switch I has passed by the aa-tRNA it can pack with domain III. Finally, when switch I packs against domain III EF-Tu can undergo a conformational change leading to EF-Tu dissociation and aa-tRNA accommodation.

The model described above gives EF-Tu a chance to detect the initial steps in accommodation. During the ~5Å movement of the aa-tRNA, EF-Tu will be able to sense with switch I if aa-tRNA is correctly positioned of the aa-tRNA. If near- or non-cognate aa-tRNAs advance beyond the GTP hydrolysis step, EF-Tu and the ribosome would need mechanisms to reject them. It is predicted that near- or non-cognate aa-tRNA will adopt misaligned positions in the A-site of the ribosome and have limited 30S domain closure [79-81]. Therefore, a misaligned aa-tRNA would reduce the rate at which it can pass by switch I via miscoordination of switch I to the acceptor stem groove of aa-tRNA, similar to our observations with EVN. The identity of the aa-tRNA accommodating also has an impact on accommodation of near-cognate aa-tRNA, suggesting certain aa-tRNA may have a higher rate for crossing the switch I barrier [82]. As the rate of aa-tRNA accommodation is thought to be closely timed with EF-Tu dissociation, even a small delay in aa-tRNA accommodation during switch I sampling of the aa-tRNA would ensure that near- or non-cognate aa-tRNA will dissociate alongside EF-Tu instead of accommodate [83].

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH NIGMS grant R01-GM072686 (to KS), by NSF, by NIH NIGMS grants R01-GM079238-13 and R01-GM098859-07 (to S.C.B) and NSERC Discovery Grant RGPIN-2016-05199 (HJW) and Alberta Innovates Strategic Chairs Program SC60-T2 (HJW). The authors thank all members of the Sanbonmatsu, Wieden, and Blanchard labs for their helpful comments, in particular, Luc Roberts who helped with data fitting. SCB holds an equity interest in Lumidyne Technologies.

Abbreviations:

- GTP

Guanosine triphosphate

- GDP

Guanosine diphosphate

- EF-Tu

Elongation Factor Tu

- DI

domain I

- DII

domain II

- DIII

domain III

- aa-tRNA

aminoacyl-tRNA

- EVN

Evernimicin

- FRET

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer

- SRL

Sarcin Ricin Loop

- kapp

apparent rate

REFERENCES

- [1].Lee JW, Beebe K, Nangle LA, Jang J, Longo-Guess CM, Cook SA, et al. Editing-defective tRNA sythetase causes protein misfolding and nuerodegeneration. Nature. 2006;443:50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Parker J. Errors and alternatives in reading the unversal genetic code. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:273–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ogle JM, Ramakrishnan V. Structural insights into translational fidelity. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:129–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mohler K, Ibba M. Translational fidelity and mistransaltion in the cellular response to stress. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].DeToma AS, Salamekh S, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH. Misfolded proteins in Alzheimer’s disease and type II diabetes. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:608–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Knowles TPJ, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM. The amyloid state and its association with protein misfolding diseases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:384–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wilson D The A-Z of bacterial translation inhibitors. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;44:393–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wilson D Ribosome-targeting antibiotics and mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Trylska J, Kulik M. Interactions of aminoglycoside antibiotics with rRNA. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016;44:987–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kapur M, Ackerman SL. mRNA translation gone awry: translation fidelity and nuerological disease. Trends Genet. 2017;34:218–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bidou L, Allamand V, Rousset JP, Namy O. Sense from nonsense: therapies for premature stop codon diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:679–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pape T, Wintermeyer W, Rodnina MV. Complete kinetic mechanism of elongation factor Tu dependent binding of aminoacyl-tRNA to the A site of the E. coli ribosome. EMBO J. 1998;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cochella L, Green R. An active role for tRNA in decoding beyond codon:anticodon pairing. Science. 2005;308:1178–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kothe U, Rodnina MV. Delayed release of inorganic phosphate from elongation factor Tu following GTP hydrolysis on the ribosome. Biochemistry. 2006;45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Berchtold H, Reshetnikova L, Reiser CO, Schiermer NK, Sprinzl M, Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of active elongation factor Tu reveals major domain rearrangements. Nature. 1993;365:126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Song H, Parsons MR, Rowsell S, Leonard G, Phillips SEV. Crystal structure of intact elongation factor EF-Tu from Escherichia coli in GDP conformaiotn at 2.05Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:1245–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kjeldgaard M, Nissen P, Thirup S, Nyborg J. The crystal structure of elongation factor EF-Tu from Thermus aquaticus in the GTP conformation. Structure. 1993;1:35–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kavaliauskas D, Chen C, Liu W, Cooperman BS, Goldman YE, Knudsen CR. Structural dynamics of translation elongation factor Tu during aa-tRNA delivery to the ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:8561–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Johansen JS, Kavaliauskas D, Pfeil SH, Blaise M, Cooperman BS, Goldman YE, et al. E. coli elongation factor Tu bound to a GTP analogue displays an open conformation equivalent to the GDP-bound form. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:8641–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Spasic A, Sitha S, Korchak M, Chu S, Mohanty U. Polyelectrolyte behavior and kinetics of aminoacyl-tRNA on the ribosome. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:4161–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Eargle J, Black AA, Sethi A, Trabuco LG, Luthey-Schulten Z. Dynamics of recognition between tRNA and Elongation Factor Tu. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:1382–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kulczycka K, Długosz M, Trylska J. Molecular dynamics of ribosomal elongatoin factors G and Tu. Eur Biophys J. 2011;40:289–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Villa E, Sengupta J, Trabuco LG, LeBarron J, Baxter WT, Shaikh TR, et al. Ribosome-induced changes in elongation factor Tu conformation control GTP hydrolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;106:1063–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lai J, Ghaemi Z, Luthey-Schulten Z. The conformational change in elongation factor Tu involves separation of its domains. Biochemistry. 2017;56:5972–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yang H, Perrier J, Whitford PC. Disorder guides domain rearrangment in elongation factor Tu. Proteins. 2018;86:1037–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Okafor CD, Pathak MC, Fagan CE, Bauer NC, Cole MF, Gaucher EA, et al. Structural and dynamics comparison of thermostability in ancient, modern, and consensus elongation factor Tus. Structure. 2018;26:118–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Warias M, Grumüller H, Bock LV. tRNA dissociation from EF-Tu after GTP hydrolysis: primary steps and antibiotic inhibition. Biophys J. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Warias M, Grumüller H, Bock LV. tRNA dissociation from EF-Tu after GTP hydrolysis and Pi release: primary steps and antibiotic inhibition. BioRxiv. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Loveland AB, Demo G, Grigorieff N, Korostelev AA. Ensemble cryo-EM elucidates the mechanism of translation fidelity. Nature. 2017;546:113–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD - Visual MOlecular Dynamics. J Molec Graphics. 1996;14:33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Arenz S, Juette MF, Graf M, Nguyen F, Huter P, Polikanov YS, et al. Structures of the orthosomycin antibiotics avilamycin and evernimicin in complex with the bacterial 70S ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:7527–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hess B, Kutzner C, Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pronk S, Páll S, Schulz R, Larsson P, Bjelkmar P, Apostolov R, et al. GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulaton toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:845–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJC. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1701–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Comparison of multiple Amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins. 2006;65:712–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Whitford PC, Noel JK, Gosavi S, Schug A, Sanbonmatsu KY, Onuchic JN. An all-atom structure-based potential for proteins: Bridging minimal models with all-atom empirical forcefields. Proteins. 2008;75:430–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Geggier P, Dave R, Feldman MB, Terry DS, Altman RB, Munro JB, et al. Conformational sampling of aminoacyl-tRNA during selection on the bacterial ribosome. J Mol Biol. 2010;399:576–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Whitford PC, Geggier P, Altman RB, Blanchard SC, Onuchic JN, Sanbonmatsu KY. Accommodation of aminoacyl-tRNA into the ribosome involves reversible excursions along multiple pathways. RNA. 2010;16:1196–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tsai MY, Zheng W, Balamurugan D, Schafer NP, Kim BL, Cheung MS, et al. Electrostatics, structure prediction, and the energy landscapes for protein folding and binding. Protein Sci. 2016;25:255–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Girodat D, Mericer E, Gzyl KE, Wieden HJ. Elongation Factor Tu’s nucleotide binding is governed by a thermodynamic landscape unique among bacterial translation factors. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:10236–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, et al. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:252–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kiefer F, Arnold K, Künzli M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:387–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Guex N, Peitsch MC, Schwede T. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: a historical perspective. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:162–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Xu Y, Vanommeslaeghe K, Aleksandrov A, MacKerell ADJ, Nilsson L. Additive CHARMM force filed for naturally occurring modified ribonucleotides. J Comput Chem 2016;37:896–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Noel JK, Chahine J, Leite VBP, Whitford PC. Capturing transition paths and transition states for conformational rearrangements in the ribosome. Biophys J. 2014;107:2881–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Vaiana AC, Sanbonmatsu KY. Stochastic gatin and drug-ribosome interactions. J Mol Biol. 2009;386:648–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Whitford PC, Sanbonmatsu KY. Simulating movement of tRNA through the ribosome during hybrid-state formation. J Chem Phys. 2013;139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yang H, Bandarkar P, Horne R, Leite VBP, Chahine J, Whitford PC. Diffusion of tRNA inside the ribosome is position-dependent. J Chem Phys. 2019;151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Levi M, Whitford PC. Dissecting the energetics of subunit rotation in the ribosome. J Phys Chem B. 2019;123:2812–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Yang H, Noel JK, Whitford PC. Anisotropic fluctuations in the ribosome determine tRNA kinetics. J Phys Chem B. 2017;121:10593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Nguyen K, Yang H, Whitford PC. How the ribosomal A-site finger can lead to tRNA species-dependent dynamics. J Phys Chem B. 2017;121:2767–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Noel JK, Whitford PC. How EF-Tu can contribute to efficient proofreading of aa-tRNA by the ribosome. Nat Commun. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Nguyen K, Whitford PC. Steric interactions lead to collective tilting motion in the ribosome during mRNA-tRNA translcoation. Nat Commun. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nguyen K, Whitford PC. Capturing transition states for tRNA hybrid-state formation in the ribosome. J Phys Chem B. 2016;120:8768–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Leininger SE, Trovato F, Nisslye DA, O’Brien EP. Domain topology, stability, and translation speed determine mechanical force generation on the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:5523–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Trovato F, O’Brien EP. Fast protein translation can promote co- and posttranslational folding of misfolding-prone proteins. Biophys J. 2017;112:1807–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ogle JM, Brodersen DE, Clemons WMJ, Tarry MJ, Carter AP, Ramakrishnan V. Recognition of cognate transfer RNA by the 30S ribosomal subunit. Science. 2001;292:897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wimberly BT, Brodersen DE, Clemons WMJ, Morgan-Warren RJ, Carter AP, Vonrhein C, et al. Structure of the 30S ribosomal subunit. Nature. 2000;407:327–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Best RB, Hummer G. Reaction coordinates and rates from transition paths. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6732–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Sanbonmatsu KY, Joseph S, Tung CS. Simulating movment of tRNA into the ribosome during decoding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15854–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].De Laurentiis EI, Mo F, Wieden HJ. Construction of a fully active Cys-less elongation factor Tu: Functional role of conserved cysteine 81. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:684–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kumar V, Chen Y, Ero R, Ahmed T, Tan J, Wong ASW, et al. Structure of BipA in GTP form bound to the ratcheted ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10944–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kihira K, Shimizu Y, Shomura Y, Shibata N, Kitamura M, Nakagawa A, et al. Crystal structure analysis of the translation factor RF3 (release factor 3). FEBS Letters. 2012;586:3705–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Al-Karadaghi S, Avarsson A, Garber M, Zheltonosova J, LIljas A. The structure of elongation factor G in complex with GDP: conformational flexibility and nucleotide exchange. Structure. 1996;4:555–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Simonetti A, Marzi S, Fabbretti A, Hazemann I, Jenner L, Urzhumtsev A, et al. Structure of the protein core of translation initation factor 2 in apo, GTP-bound and GDP-bound forms. Acta Crystallogr D. 2013;69:925–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Czworkowski J, Wang J, Steitz TA, Moore PB. The crystal structure of elongation factor G complexed with GDP, at 2.7Å resolution. EMBO J. 1994;13:3661–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Gagnon MG, Lin J, Bulkley D, Steitz TA. Crystal structure of elongation factor 4 bound to a clockwise ratcheted ribosome. Science. 2014;345:684–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Yoshizawa S, Böck A. The many levels of control on bacterial selenoprotein synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1404–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Leibundgut M, Frick C, Thanbichler M, Böck A, Ban N. Selenocysteine tRNA-specific elongation factor SelB is a structural chimaera of elongation and initation factors. EMBO J. 2005;24:11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Fischer N, Neumann P, Bock LV, Maracci C, Wang Z, Paleskava A, et al. The pathway to GTPase activaiton of elongation factor SelB on the ribosome. Nature. 2016;540:80–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Li W, Liu Z, Koripella RK, Langlois R, Sanyai S, Frank J. Activation of GTP hydrolysis in mRNA-tRNA translocation by elongation factor G. Sci Adv. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Verstraeten N, Fauvart M, Versées W, Michiels J. The universally conserved prokaryotic GTPases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011;75:507–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Blanchard SC, Kim HD, Gonzalez RLJ, Puglisi JD, Chu S. tRNA dynamics on the ribosome during translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12893–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Caban K, Pavlov M, Ehrenberg M, Gonzalez RLJ. A conformational switch in initiation factor 2 controls the fidelity of translation initiation in bacteria. Nat Commun. 2017;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Choi J, Puglisi JD. Three tRNAs on the ribosome slow translation elongation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:13691–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Meskauskas A, Dinman JD. Ribosomal protein L3: gatekeeper to the A site. Mol Cell. 2007;25:877–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Sanbonmatsu KY. Alignment/misalignment hypothesis for tRNA selection by the ribosome. Biochimie. 2006;88:1075–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Khade PK, Shi X, Joseph S. Steric complementarity in the decoding center is importnat for tRNA selection by the ribosome. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:3778–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Zeng X, Chugh J, Casiano-Negroni A, Al-Hashimi HM, Brooks CL. Flipping of the ribosomal A-site adenines provides a basis for tRNA selection. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:3201–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Zhang J, Ieong KW, Johansson M, Ehrenberg M. Accuracy of initial codon selection by aminoacyl-tRNAs on the mRNA-programmed bacterial ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:9602–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Morse JC, Girodat D, Burnett BJ, Holm M, Altman RB, Sanbonmatsu KY, et al. Elongation factor-Tu can reversibly engage both aminoacyl-tRNA and the ribosome during the proofreading stage of tRNA selection. PNAS, in review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.