Abstract

Background

As of 26 March 2021, the Africa CDC had reported 4,159,055 cases of COVID-19 and 111,357 deaths among the 55 African Union Member States; however, no country has published a nationally representative serosurvey as of May 2021. Such data are vital for understanding the pandemic's progression on the continent, evaluating containment measures, and policy planning.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, nationally representative, age-stratified serosurvey in Sierra Leone in March 2021 by randomly selecting 120 Enumeration Areas throughout the country and 10 randomly selected households in each of these. One to two persons per selected household were interviewed to collect information on socio-demographics, symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, exposure history to laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases, and history of COVID-19 illness. Capillary blood was collected by fingerstick, and blood samples were tested using the Hangzhou Biotest Biotech RightSign COVID-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Cassette. Total seroprevalence was was estimated after applying sampling weights.

Findings

The overall weighted seroprevalence was 2.6% (95% CI 1.9-3.4). This is 43 times higher than the reported number of cases. Rural seropositivity was 1.8% (95% CI 1.0-2.5), and urban seropositivity was 4.2% (95% CI 2.6-5.7).

Interpretation

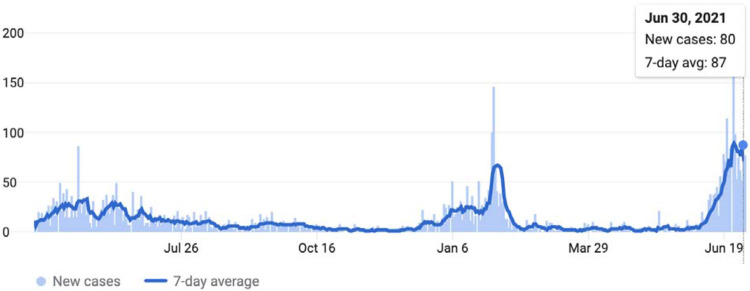

Although overall seroprevalence was low compared to countries in Europe and the Americas (suggesting relatively successful containment in Sierra Leone), our findings indicate enormous underreporting of active cases. This has ramifications for the country’s third wave (which started in June 2021), where the average number of daily reported cases was 87 by the end of the month—this could potentially be on the order of 3,700 actual infections, calling for stronger containment measures in a country with only 0.2% of people fully vaccinated. It may also reflect significant underreporting of incidence and mortality across the continent.

Background

As of 26 March 2021, the Africa CDC had reported 4,159,055 cases of COVID-19 and 111,357 deaths among the 55 African Union Member States;1 no African Union (AU) Member States has published a nationally representative COVID-19 antibody serosurvey as of May 2021.

Sierra Leone reported 3,962 cases (49.5 per 100,000 population) and 79 deaths as of 26 March 2021 (Figure 1), with 2.9% of all RT-PCR tests becoming positive. This relatively low case rate compared with countries in Europe and the Americas could be partly explained by the fast implementation of stay-at-home measures, collaboration at regional levels, and a swift response at the continental level.2 Indeed, Ministers of Health and the Africa CDC convened to develop a continental strategy early in the pandemic.3,4

Figure 1.

Daily COVID cases in Sierra Leone until from Feb 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021. The country’s first case was reported on March 31, 2020. (Source: COVID-19 Dashboard by the by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. Accessed July 2, 2021).

To date, however, all reported data on cases and deaths have come from event-based surveillance.5 Case reporting is influenced by often under-resourced strategies for case finding, testing, and contact tracing, and might underestimate the true burden of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.6 We therefore sought to measure country-wide seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Sierra Leone, an AU Member State, as such data are vital for understanding the pandemic's progression in the country and on the continent, as well as for evaluating containment measures and policy planning.7

Methods

Design

This was a cross-sectional, population-based, age-stratified serosurvey, targeting household members aged 5 years or above, regardless of previous or current infection with COVID-19, who resided in Sierra Leone during the period of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (that is, since the first case was reported on March 31, 2020).

For the purpose of sample size estimation, seroprevalence was estimated at 5%. Considering 95% confidence intervals and a design effect of 3, the minimum sample size was calculated to be 1,200 households with at least one member of each household selected. This was designed to give a total of 240 individuals for each of the age strata 5-9, 10-19, 20-39, 40-59 and ≥60 years old.

Sampling

The sampling frame was the most recent census conducted by Statistics Sierra Leone.8 We conducted randomized, multistage sampling, with the first stage consisting of 120 randomly chosen Enumeration Areas (EAs), which are small units that contain 80-120 households each. Within each selected EA, households were identified on a satellite map by numbering them in order west to east, then north to south. After that, 10 households were chosen using a random number generator. One to two members of each household over the age of 5 years were then selected for participation, and the selection of individuals was constrained to give a comparable number of individuals for each age stratum: In Sierra Leone, approximately 41% of the population is aged ≤ 15 years and only about 3.5% are aged ≥ 65 years.8 This means that any straight-forward random sample of the population will result in an insufficient sample of older adults. For example, a truly random sample of the population that selected 1,000 people, would include 410 children aged ≤ 15 years and only 35 adults aged ≥ 65 years. This would result in a sample too small to give confidence in the estimated seroprevalence of senior adults. To compensate for this, the sampling process was constrained to restrict the number of children selected, and adults were over-sampled.

We started by selecting individuals from the older strata in a systematic progression from house-to-house. In this method, the survey team would attempt to capture an individual of each sex in the older strata before progressing to younger strata. If there was not any individual available for the appointed age group, they would skip to the next younger age stratum and choose from that one.

Test Validation and Sample collection

Fingerstick samples were screened for the presence of both IgM and IgG SARS-CoV-2 virus specific antibodies using the Hangzhou Biotest Biotech RightSign COVID-19 Rapid Test Cassette, which in FDA testing had combined IgM/IgG specificities of 100% and IgM/IgG sensitivities of 100%.9 We further validated the test with a control panel of 58 serum samples (from 18 persons tested by NP swab—10 who tested negative and 8 positive, with 5 serial dilutions of each positive) and also found combined IgM/IgG sensitivities and specificities of 100%.

All tests were performed at the time of interview and according to manufacturer’s instructions. Each participant was notified of their results during the interview. Participants with positive IgM results were referred to the District Health Management Team as an active case.

Data analysis

We collected demographic data on study participants including age, sex, district, number of people per household, occupation, and whether they lived in a rural or urban area (those residing in district capitals were categorized as urban, and the rest as rural). As in other surveys, we categorized the reported occupations into high-risk and low-risk categories on the basis of the risk of exposure to potential COVID-19 cases.6 For example, occupations such as health-care workers, shopkeepers or petty traders, transport operators, and those in food service were considered high-risk occupations; on the other hand, farmers, miners, homemakers, students, were considered as being at lower risk of exposure. The information about occupation of the participants was captured as open-ended text and was categorized into high and low risk by the investigators.

The data were analyzed to estimate an unadjusted seroprevalence of IgM/IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 with 95% CI. An individual was deemed seropositive if they were IgM+/IgG−, IgM−/IgG+, or IgM+/IgG+. We also calculated seroprevalence by age group, sex, and area of residence (rural/urban). To estimate the weighted seroprevalence, we post-stratified by district (counting Falaba as part of Koinadugu) and calculated sampling weights as a ratio of the national population to district population (aged >5 years). We then dtermeined if there were significant differences in seropostivity by demographic variable using the Rao-Scott Chi-square test.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee. It received a Not Research Determination (IRB20-1394) from the Harvard Institutional Review Board as it was deemed Public Health Surveillance.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study were not involved in reviewing the study design, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. All authors had access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Findings

In March, 2021, we identified 1,893 individuals aged 5 years or older from households in 120 EAs. Three hundred forty (18%) of the participants were age 5-9; 384 (20.3%) 10-19; 451 (23.8%) 20-39; 359 (19.0%) 40-59; and 359 (19.0%) >60. Slightly more than half of the participants (964, 50.9%) were female; 1,174 (62%) were residing in rural areas, and 845 (44.6%) had an occupation with a relatively higher risk of exposure to people potentially infected with COVID-19. No individuals reported having previously tested positive for COVID-19 (Table 1).

Table 1:

Participant characteristics.

| Participants (n=1,893) |

|

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| < 10 | 340 (18.0%) |

| 10-19 | 384 (20.3%) |

| 20-39 | 451 (23.8%) |

| 40-59 | 359 (19.0%) |

| > 60 | 359 (19.0%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 964 (50.9%) |

| Male | 929 (49.1%) |

| Area of residence | |

| Rural | 1,174 (62.0%) |

| Urban | 719 (38.0%) |

| Number of People Per Household (n = 1,719)§ |

7 (5-9)* (1-45)† |

| Occupation with high risk of exposure to COVID-19 (n = 1,892)§ |

845 (44.6%) |

| Current smoker (n = 1,892)§ |

250 (13.2%) |

| Would accept vaccine if offered (n = 1,892)§ |

1,666 (88.0%) |

| Seropositive | 53 (2.8%) |

| Positive IgM | 12 (0.6%) |

| Positive IgG | 44 (2.3%) |

median (interquartile range)

(absolute range)

Data are n (%) unless otherwise stated

The overall weighted and adjusted seroprevalence was 2.6% (95% CI 1.9-3.4). IgM positivity was 0.6% and IgG positivity was 2.3%; only 6 participants (0.3%) were IgM+/IgG+. Rural weighted seropositivity was 1.8% (95% CI 1.0-2.5) and urban seropositivity was 4.2% (95% CI 2.6-5.7). Stratifying by age group and weighting, 1.7% (95% CI 0.2-3.2) of participants age 5-9 tested positive for anti-SARS-CoV-s antibodies, as did 2.6% (95% CI 0.8-4.2) of those 10-19, 1.2% (95% 0.2-2.3) of those 20-39, 4.4% (95% CI 2.4-6.4) of those 40-59, and 3.6% (95% CI 1.6-5.6) of those 60 and above (Table 2). None of the 35 healthcare workers sampled tested positive. There was a significant difference in seropositivity between rural and urban populations (Rao-Scott Chi-square p=0.002). Seropositivity in females was 74% higher than in males, nearly reaching significance (Rao-Scott Chi-square p=0.056).

Table 2:

Seroprevalence by demographic characteristics.

| Participants tested, n |

Seropositive participants, n |

Unweighted Seroprevalence, % (95% CI) |

Weighted Seroprevalence, % (95% CI)* |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1,893 | 53 | 2.8% (2.1-3.5) | 2.6% (1.9-3.4) |

| Age, years | ||||

| < 10 | 340 | 5 | 1.5% (0.5-3.4) | 1.7% (0.2-3.2) |

| 10-19 | 384 | 9 | 2.3% (1.1-4.4) | 2.6% (0.8-4.2) |

| 20-39 | 451 | 6 | 1.3% (0.5-2.9) | 1.2% (0.2-2.3) |

| 40-59 | 359 | 19 | 5.3% (3.2-8.1) | 4.4% (2.4-6.4) |

| > 60 | 359 | 14 | 3.9% (2.1-6.5) | 3.6% (1.6-5.6) |

| Rao-Scott Chi-sq p-value | 0.0032 | 0.0548 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 964 | 33 | 3.4% (2.4-4.8) | 3.3% (2.2-4.5) |

| Male | 929 | 20 | 2.2% (1.3-3.3) | 1.9% (1.0-2.8) |

| Rao-Scott Chi-sq p-value | 0.0939 | 0.0563 | ||

| Area of residence | ||||

| Rural | 1,174 | 24 | 2.0% (1.3-3.0) | 1.8% (1.0-2.5) |

| Urban | 719 | 29 | 4.0% (2.7-5.7) | 4.2% (2.6-5.7) |

| Rao-Scott Chi-sq p-value | 0.0109 | 0.0023 | ||

post-stratified by district

Interpretation

Our findings indicate that 2.6% of Sierra Leone’s population aged 5 years or older had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 infection by March 2021, with an estimated 203,060 infections. This is 43 times higher than the reported number of cases, which may give an idea of the potential disease burden as of June 30, 2021, where the average number of daily reported cases was 87 (represeting the onsent of the third wave in the country, Figure 1).3 Furthermore, this finding demonstrates that, similar to many other countries,10 herd immunity is far from being reached in Sierra Loene. Notably, seroprevalance in urban settings was more than double that of rural. This trend has been seen in other surveys and can be explained by higher contact rates and challenges in safe physical distancing in urban areas.6

While a total seroprevalence of 2.6% is significantly lower than city and regional estimates across the continent, it represents the first nationally representative SARS-CoV-2 serosurvey to be published by an African nation. (Of note, West Africa was one of the last regions of the world to be affected by H1N1 influenza in 2009-2010,11 so a similar dynamic may be occurring here.) Chibwana and colleagues found that 12.3% of healthcare workers in Blantyre, Malawi tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies;12 Uyoga and colleagues found a crude seroprevalence of 5.6% in Kenyan blood donors;13 Olayanju and colleagues determined a 45.1% seroprevalence among asymptomatic healthcare workers in Ibadan, Nigeria;14 and Mulenga and colleagues noted a SARS-CoV-2 prevalence of 10.6% in 6 of 117 districts in Zambia.15

Significant underreporting of cases may be the result of a high prevalence of minimally symptomatic disease in a younger demographic coupled with under-resourced systematic surveillance in the setting of legacies of distrust of authorities and foreign interventions (resulting in the avoidance of testing).16-24 Indeed, Mwananyanda and colleagues found significant underreporting of cases in Zambia through postmortem surveillance.25 Furthermore, 1) limited testing capacity, 2) low acquired immunity to SARS-CoV-2, 3) and less than 0.2% of Sierra Leoneans being fully vaccinated as of 21 May 2021 is extremely concerning in that it presents a very large population of susceptible individuals at risk for future variant waves. As reported by Reuters, during the first week of May 2021, Sierra Leone averaged about 556 doses of vaccine administered each day: At that rate, it would take 2,809 days (7.7 years) to administer enough doses for 10% of the population.26 Indeed, both under-reporting of cases and limited vaccination campaigns increase the risk of new variants emerging and circulating in the population before public health authorities have a chance to detect them and prevent their spread.27 Since India was forced to halt the export of vaccines on account of the devastating second wave there, this timeline could worsen.28 These data should therefore strengthen demands for faster vaccine deployments in countries like Sierra Leone as part of global vaccine justice, including support for intellectual property waivers and technology transfers.29

Our study has two notable limitations. The effects of waning immunity on the performance of the assay we used is unclear, and we therefore may not have fully captured those individuals infected in the first wave of COVID-19 in spring 2020 (Figure 1).30 In addition, the exact sensitivity of the assay for detecting minimally symptomatic infection is not known. Both factors would bias the estimated seroprevalence downwards.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yelena Gorina for her help with data analysis.

Funding

This study was supported by NIAID K08 AI139361, the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, and the Africa CDC.

Footnotes

Disclosure

We declare no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- 1.Africa CDC. COVID-19 Dashboard. 2021. https://africacdc.org/covid-19/ (accessed March 26, 2021).

- 2.Binagwaho A, Mathewos K. What explains Africa’s successful response to the COVID-19 pandemic? Medical News Today. 2020. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/what-explains-africas-successful-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic#Swift-response-at-the-continental-level (accessed March 26, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2020; 20: 533–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Africa CDC. Africa Joint Continental Strategy for COVID-19 Outbreak. 2020. https://africacdc.org/download/africa-joint-continental-strategy-for-covid-19-outbreak/ (accessed March 26, 2021).

- 5.Salyer SJ, Maeda J, Sembuche S, et al. The first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet 2021; : [Epub before print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murhekar M V, Bhatnagar T, Selvaraju S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in India, August-September, 2020: findings from the second nationwide household serosurvey. The Lancet Global Health 2021; 9: e257–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murhekar M V, Clapham H. COVID-19 serosurveys for public health decision making. The Lancet Global Health 2021; 9: e559–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Statistics Sierra Leone. Population and Housing Census. 2015. https://www.statistics.sl/images/StatisticsSL/Documents/final-results_-2015_population_and_housing_census.pdf (accessed June 21, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.FDA. Serology Test Evaluation Report for “Covid-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test Cassette” from Hangzhou Biotest Biotech, Co., Ltd. 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/presentations/maf/maf3252-a001.pdf (accessed March 26, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, Chen Z, Azman AS, et al. Serological evidence of human infection with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health 2021; 9: e598–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Situation updates - Pandemic (H1N1) 2009. 2010. https://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/updates/en/.

- 12.Chibwana MG, Jere KC, Kamng’ona R, et al. High SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in health care workers but relatively low numbers of deaths in urban Malawi. Wellcome Open Research 2020; 5. DOI: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16188.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uyoga S, Adetifa IMO, Karanja HK, et al. Seroprevalence of anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in Kenyan blood donors. Science 2021; 371: 79 LP–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olayanju O, Bamidele O, Edem F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Seropositivity in Asymptomatic Frontline Health Workers in Ibadan, Nigeria. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2020; 104: 91–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulenga LB, Hines JZ, Fwoloshi S, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in six districts in Zambia in July, 2020: a cross-sectional cluster sample survey. The Lancet Global Health 2021; : [Epub before print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Usuf E, Roca A. Seroprevalence surveys in sub-Saharan Africa: what do they tell us? The Lancet Global Health 2021; published online May 18. DOI: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson ET. On the Coloniality of Global Public Health. Medicine Anthropology Theory 2019; 6: 101–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson ET. Epidemic Illusions. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankfurter R, Kardas-Nelson M, Benton A, et al. Indirect Rule Redux: The Political Economy of Diamond Mining and its Relation to the Ebola Outbreak in Kono District, Sierra Leone. Review of African Political Economy 2018; 45: 522–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson ET, Kelly JD, Sesay O, et al. The Symbolic Violence of ‘Outbreak’: A Mixed-methods, Quasi-experimental Impact Evaluation of Social Protection on Ebola Survivor Wellbeing. Social Science and Medicine 2017; 195: 77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson ET, Barrie MB, Kelly JD, Dibba Y, Koedoyoma S, Farmer PE. Biosocial approaches to the 2013-16 Ebola pandemic. Health and Human Rights 2016; 18: 167–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunn N, Wantchekon L. The Slave Trade and the Origins of Mistrust in Africa. American Economic Review 2011; 101: 3221–52. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson ET, McGinnis T, Frankfurter R. Ebola and the narrative of mistrust. BMJ Global Health 2019; 4: e001932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daniel Kelly J, Barrie MB, Mesman AW, et al. Anatomy of a Hotspot: Chain and Seroepidemiology of Ebola Virus Transmission, Sukudu, Sierra Leone, 2015-16. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2018; 217. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jiy004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mwananyanda L, Gill CJ, MacLeod W, et al. Covid-19 deaths in Africa: prospective systematic postmortem surveillance study. BMJ 2021; 372: n334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reuters. Sierra Leone. COVID-19 Tracker. 2021. https://graphics.reuters.com/world-coronavirus-tracker-and-maps/countries-and-territories/sierra-leone/. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wild S. Hidden Toll of COVID in Africa Threatens Global Pandemic Progress. Scientific American 2021; published online March. [Google Scholar]

- 28.AFP. India’s COVID battle causes vaccine worries in Africa. Al Jazeera. 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/5/10/indias-covid-battle-causes-vaccine-worries-in-africa?taid=609a1660d8fc9d0001741dc0&utm_campaign=trueAnthem%3A+Trending+Content&utm_medium=trueAnthem&utm_source=twitter. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harman S, Erfani P, Goronga T, Hickel J, Morse M, Richardson ET. Global vaccine equity demands reparative justice — not charity. BMJ Global Health 2021; 6: e006504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peluso MJ, Takahashi S, Hakim J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody magnitude and detectability are driven by disease severity, timing, and assay. medRxiv 2021; : 2021.03.03.21251639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]