Abstract

In this study, we aimed to address female circumcision (FC) from sociocultural, medical, ethical, and religious/Islamic perspectives through the understanding of a Muslim surgeon. FC is performed primarily in Africa today, and its prevalence varies across countries. None of the sociocultural justifications developed historically for FC is scientifically valid. FC provides no health benefits; on the contrary, severely impairs the physical, psychological, and social health of the victim in the short and long term. As for sexual health and satisfaction, the outcome is disastrous. Hoodectomy as another relevant surgical intervention, however, can be distinguished as an exception because it can rarely be for the benefit of the woman. When we assess FC ethically, we see that all of the generally accepted, major principles of biomedical ethics are violated. If we consider FC from an Islamic perspective, the Quran does not contain any verses to ground or adjudicate arguments on FC. The hadiths reporting about the justification of FC have been determined by the hadith scholars to be weak. They have not been accepted as sound justificatory sources that a fatwa can be based on. The author, along with many contemporary Islamic scholars, believes that FC should be abandoned.

Keywords: Female circumcision, sexual health, sexual dysfunction, culture, religion, ethics

Introduction

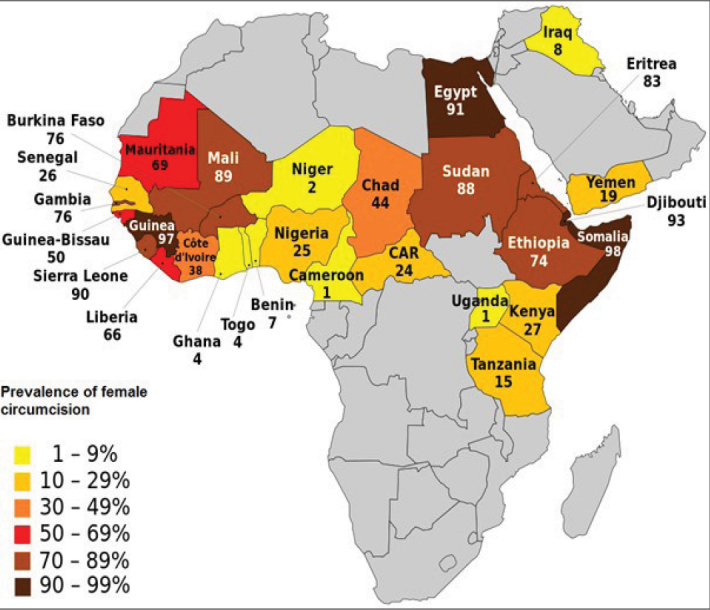

As a tradition that has been in place almost since 4000 BC, female circumcision (FC) is usually associated with the norms and values adhered to by patriarchal societies. It is currently applied in certain areas in the world with varying prevalence rates in each area. Prevalence of FC is over 70% in Somalia, Egypt, Guinea, Ethiopia, Mali, Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti, and Sierra Leone; whereas it is below 10% in Ghana, Niger, Cameroon, and Uganda, although all of them are African countries. In addition to the African continent, girls and women are known to be circumcised in Iraq, Yemen, Oman, Afghanistan, Malaysia, and Indonesia as well[1–5] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of female circumcision

Statistical data on FC include the following: Today, over 125 million girls and women are circumcised in 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East. The procedure is performed from infancy till 15 years of age.[6] Of all FC operations, only 18% are performed by healthcare workers, and it is known that FC is gradually getting medicalized in the Far East in particular.[7–10] However, every year, 20,000 girls under the age of 15 are faced with the risk of getting circumcised even in Britain, where 66,000 women are already trying to cope with the long-term complications of circumcision.[8, 11, 12] FC has been a concern in USA, UK, France, and some other western countries as a result of immigration from countries where FC is practiced.[13]

Predominantly performed in Africa, the tradition of FC is usually performed by a female circumciser without medical training. The procedure is often done using a knife, scissors, scalpel, blade, or pieces of glass and without anesthetics and antiseptics. Naturally, in agony during the procedure, the child is restrained by a few assistants by force and sometimes violently.[14, 15]

This study discusses FC from four different perspectives; sociocultural, medical, ethical, and religious/Islamic perspectives.[16]

Female circumcision

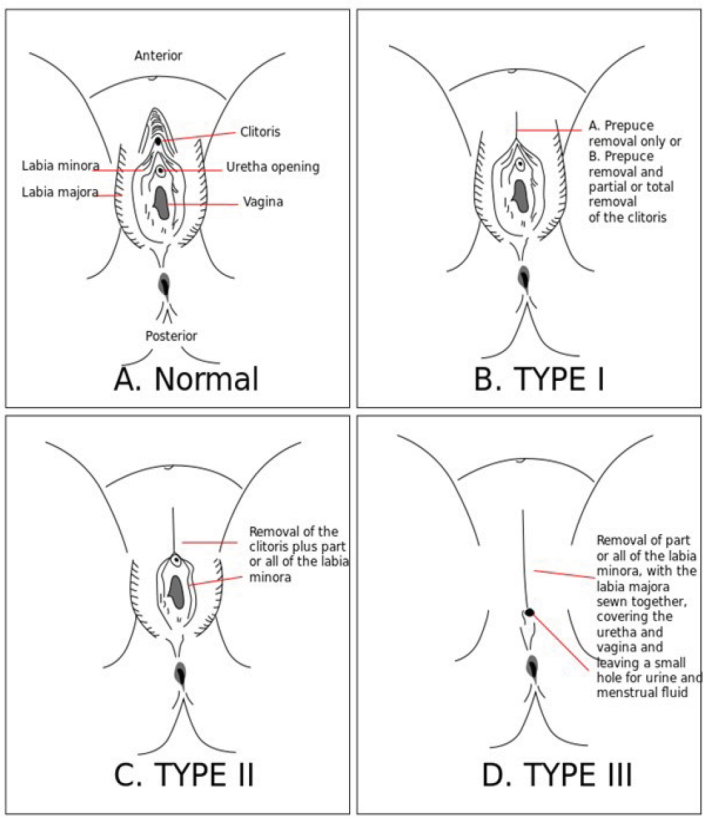

Western nomenclature on FC has changed over time. Today, the terms female circumcision, female genital mutilation, and female genital cutting are used in the English literature. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined four types of FC[15, 17–21] (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

WHO’s definition of female genital mutilation for the first three types

-

Type 1

A) Prepuce removal only - hoodectomy

B) Partial or total removal of the clitoris along with prepuce - clitoridectomy [22]

Type 2: Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without the excision of labia majora - excision

Type 3: Removal of the labia minora, with the labia majora sewn together, leaving a small vaginal opening - infibulation

Type 4: Unclassified; includes pricking, piercing, or incising the clitoris and/or labia; cauterization by burning of the clitoris and surrounding tissue, and so forth.

The impact of FC on the victims and their families could be discussed from four different perspectives; namely, sociocultural, medical, ethical, and religious/Islamic perspectives.[23–26]

Female circumcision from a sociocultural perspective

From a sociocultural perspective, the following justifications have been historically used for FC[27, 28]:

Protection and proof of virginity as a prerequisite for an honorable marriage

Purifying/cleaning women

A prerequisite for becoming a woman in its full sense

Preventing extreme sexual pleasure in women

Protecting women against various disorders such as hysteria or over masturbation

Preventing mental disorders such as depression, insanity, and kleptomania

Reducing sexual desire and restraining women from promiscuity

Ensuring a high social status for women

Preventing infertility

None of these arguments is scientifically validated and are simply “myths.”[20]

Female circumcision from a medical perspective

In contrast to the many proven benefits of male circumcision from a medical perspective, FC has no medical health benefits.[17, 28, 29] On the contrary, it leads to several short-term and long-term health problems, some of which are not reconcilable with life. Medical disadvantages of FC can be classified into two groups, which involve early and long-term complications[17, 28, 30–32]:

Early complications:

Acute pain

Shock

Hemorrhage

Tetanus, necrosis, systemic or local infection with HIV, hepatitis B and C, and other viruses

Inability to urinate

Damage/injury to neighboring organs such as urinary canal and the intestines

Death

Long-term complications:

Chronic vaginal or lower abdominal infections

Menstrual irregularities, painful menstruation, obstruction of menstrual flow

Difficulty with urination and persistent urinary tract infections

Urinary incontinence

Renal failure

Injuries to the reproductive system and infertility

Abscess, scars, and cyst formation

Pregnancy complications and neonatal deaths

Painful and unpleasant sexual intercourse

Psychological trauma, loss of motivation, anxiety, and depression

A medical perspective on FC paints a more devastating picture with regard to sexual health and happiness. The clitoris and labia minora, the parts of the genitalia that are mutilated by circumcision, are covered by rich neural networks and are sensitive to sexual stimulation. Sexual stimulation and pleasure increases vaginal secretion, preparing the woman and thus, the man, for a comfortable sexual intercourse. Loss of such sensitive organs results in vaginal dryness making it more difficult to have pleasure and orgasm.[6] In case of repetition, this gradually evolves into sexual frigidity and unhappiness. It leads to sexual dysfunction, first in the woman and later in man. Narrowing of the vaginal opening as performed in certain types of FC causes pain and hemorrhage during penis penetration in sexual intercourse.

However, there is an exception to FC, called hoodectomy or clitoral hood reduction.[33–36] This procedure deserves additional explanation.

The hood (prepuce) is a fold of skin surrounding the glans penis in men and the clitoris in women. It is the part that is removed in male circumcision. In some girls, this fold of skin is redundant or overdevelops during puberty, thus covering the clitoris entirely and preventing sufficient contact between the penis and the clitoris during sexual intercourse as well as causing discomfort for woman because of squeezing under the pressure of male external genitalia. This results in a loss of stimulation, preventing the woman from having pleasure and orgasm. Removal of such redundant folds of skin through hoodectomy (clitoral hood reduction) increases pleasure during intercourse and facilitates orgasm. The presence of such redundant skin is a real medical indication for surgery, and its removal is beneficial to sexual health. Today, clitoral hood reduction and similar types of hoodplasties are among the most common aesthetic genital surgeries in the western countries.[34, 37]

In a 1979 report, WHO underlined the fact that this type of surgical intervention does not present any harm. “With regard to the type of FC which involves removal of the prepuce of the clitoris, which is similar to male circumcision, no harmful health effects have been noted.”[38] Thabet and Thabet[39] have also showed that individuals who underwent type-1A FC (hoodectomy only) is not different from uncircumcised women in terms of sexual scores obtained from both groups.

Female circumcision from an ethical perspective

From an ethical perspective, FC undoubtedly violates all universally recognized and fundamental ethical principles, which are:

FC is a procedure that violates the principle of justice in that it mutilates a woman’s body to execute certain social or patriarchal traditions; autonomy in that it is often performed without the woman’s consent and even forcibly; beneficence in that it provides no health benefits, either psychologically or physiologically; and non-maleficence in that it not only lacks any benefits but also mutilates the woman’s body and harms the overall health of the individual.

Female circumcision from an Islamic perspective

From an Islamic perspective, there is no Quranic reference, as the primary source of Islamic law, to any type of FC. As the second major source of Islamic law, the most renowned hadiths (authentic sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) on female circumcision cited in the relevant texts are as follows:

As narrated by Abu Dawood, a woman (Umm Atiyyah al-Ansariyyah) used to perform FC in Medina. The Prophet (peace be upon him [pbuh]) said to her, “Do not overdo it because that [clitoris] is lucky for the woman and dear to the husband.” As narrated by Hadrat Ali, the Prophet (pbuh) sent for a female circumciser and told her, “When you circumcise, cut slightly and not too deep.” According to another account, the Prophet (pbuh) said, “O the women of al-Ansar! Get circumcised but do not overdo it and avoid being ungrateful for the favors bestowed upon you.”[42, 43]

There are also other accounts that “circumcision is a sunnah (tradition of the Prophet) for men and makrumah (an honorable deed, ennobling act) for women” (Ahmad b. Hanbal, Abu Dawood). The related hadiths on the issue are generally considered to be da‘if (weak) by scholars, who view them as not sound and authentic enough to serve as a basis for fatwa. It is known that Prophet Muhammad and Prophet Abraham did not prescribe or require their daughters and granddaughters to undergo circumcision. Moreover, none of the terms fitrah (creation), shiar (principle), and makrumah (honorable deed) mentioned in the sources on sunnah provide justification for the obligatory character of circumcision according to Islamic jurisprudence.[8, 42, 43]

Classical jurists hold that FC is wajib (required) for the Shafi school and sunnah (recommended) for the Maliki and Hanbali schools. Nevertheless, on the basis of modern medical knowledge and advances, these views are not necessarily acceptable given the harmful impacts of circumcision on women’s spiritual, physical, and sexual health. A majority of modern jurists describe FC as jaiz or mubah (permissible). Yet, the procedure is deemed makruh (disallowed) if it poses any significant risks to the woman’s health and haram (prohibited) in case it puts her life in jeopardy.[13, 43–45]

Regarding severe forms of FC, Elchalal et al.[13] have clearly stated that it is an apparent misinterpretation of Islamic law. Hoosen[43] made a righteous conclusion at the end of her analysis of FC in the light of Islamic jurisprudence, “Finally, according to Islamic law, any cultural practice that causes harm to a person is not acceptable. As the practice causes pain, distress, and often results in medical complications and has no known benefits, the practice must be abandoned.”

However, the abovementioned hoodectomy procedure should be evaluated in a different light from a jurisprudential perspective as the procedure is performed by removing only a part of the prepuce covering the clitoris when necessary (similar to male circumcision). It is therefore:

Harmless,

Beneficial, and

Increases sexual pleasure and satisfaction, both for women and men.

Hoodectomy is reconcilable with the narrated hadiths in logical, scientific, and experimental terms for there is no overdoing in this procedure, which is good and pleasing for women and men alike, and thus could be considered as makrumah.

The most up-to-date jurisprudential perspective on FC could be summarized according to the views of Prof. Hayreddin Karaman of Turkey, a leading Islamic law scholar of the country; and Yusuf al-Qaradawi, the top cleric of the Islamic world at large. To quote Karaman[46]:

“There is a custom practiced by certain societies, which involves total or partial removal of the clitoris of young girls. This is called FC and is known to be in practiced in certain countries at least since the time of the Egyptian pharaohs.

Male circumcision has positive effects and is beneficial in terms of both cleanliness and pleasure; however, FC has no benefit at all and in fact, causes significant harm and involves mutilating and cutting out a God-given organ with important functions, just so that women will not go astray and preserve their chastity.

FC is an issue that non-Islamic communities abuse by associating it with Islam. It is unfair to attribute this procedure to the religion, although it is not prescribed by the Quran, sound and clear hadiths, ijma (consensus) and qiyas (reasoning by analogy) “as an Islamic obligation.” It is also improper or even harmful to advocate it.

It is medically inadvisable to partly or totally cut off a normally functioning clitoris, with no mention of any benefit, whatsoever. In fact, most Muslim societies do not practice this custom. Today, it is only partially in place in certain countries in Africa, the Middle East, and the Far East.

From my readings, I have reached the conclusion that there is no religious practice such as FC in Islam. This has only been practiced by certain communities as a custom and tradition. During the time of the Prophet (pbuh), people used to practice it as an ennobling act (makrumah). However, our Prophet reminded those who practiced it of the advantages of the clitoris, advising them to “not overdo it.”

I took up the matter once again as I intended to discuss certain issues abused by the opponents of Islam. I read on the website of a contemporary scholar, Yusuf al Qaradawi, that he shares the same opinion, refuting the justifications of those who advocate it in the name of religion.

Furthermore, I learned that a scholarly conference was held under the sponsorship of al-Azhar University in November 2006 and attended by many scholars and experts from around the world.[44, 47, 48]

The most important decisions adopted during this meeting were as follows:

Allah created all humans, men and women alike, as precious and sacred beings.

FC is a customary practice performed by some people with no Islamic ground, be it Quran or sound hadiths.

Islam prohibits inflicting any physical or moral harm on any human being. This tradition inflicts significant physical and psychological harm on women.

The participants of the meeting advise Muslims to renounce this harmful practice, strive to raise consciousness among the people, and urge governments to take legal measures against it.”

Qaradawi has following views on the matter[46, 49]:

There is no evidence in the Quran, sunnah, ijma, and qiyas that FC is fard (obligatory), wajib (required), or mustahabb (recommended).

The relevant hadiths (or accounts) are either weak or do not involve a binding provision.

This practice can be considered “permissible if not harmful” at best.

Some pre-Islamic tribes developed this habit, and the Prophet (pbuh) did not prohibit it as it was a custom. However, he told them “not to overdo it.”

Today, the ummah at large has abandoned the practice of FC.

Medical authorities unanimously agree that cutting out the clitoris in particular is harmful.

Therefore, this procedure should be banned according to the rule that “it is permissible to prohibit a permissible act by ula al-amr (those vested with authority) when it proves to cause harm.”

Conclusion

After clearly noting that FC mainly originates from sociocultural myths and ancient traditions, cannot be reconciled with medical ethics, and has no medical health benefits, whatsoever; it would be proper to re-state the conclusion of Prof. Karaman[46] as a religious/Islamic conclusion: Islam does not require FC as a religious duty and does not advice or encourage it. Similarly, jurists have historically put forth different opinions such as wajib (required), jaiz (permissible), or mustahabb (recommended) but did not reach a consensus that it was indeed “an Islamic duty.” Consequently, Islam has to be held harmless from accusations and slanders, such as, “Islam prescribes FC, which is torture, murder, and atrocity.”

Finally, as a Muslim surgeon, I strongly advocate that the practice of FC should be abandoned as it has never been mandated in Islam, and the health hazards of FC are clearly documented.

Main Points.

Female circumcision (FC), which mainly originated from sociocultural myths and ancient traditions, is performed primarily in Africa and some Middle East countries today.

This procedure severely impairs the physical, psychological, sexual, and social health of the victim in the short and long term.

FC undoubtedly violates all universally recognized and fundamental ethical principles and human rights.

From a religious perspective, Islam does not require FC as a religious duty and does not advice or encourage it.

Therefore, along with many contemporary Islamic scholars, we believe that FC should be abandoned.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Conflict of Interest: The author have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The author declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) Female genital mutilation/cutting: a statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: www.unicef.org/publications/index_69875.html.

- 2.United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) The state of the world’s children 2015 executive summary. [Accessed February, 2020]. www.unicef.org/publications/files/SOWC_2015_Summary_and_Tables.pdf.

- 3.Wikimedia Commons. FGM prevalence, UNICEF. 2015. [Accessed February, 2020]. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FGM_prevalence_UNICEF_2015.svg.

- 4.Oringanje CM, Okoro A, Nwankwo ON, Meremikwu MM. Providing information about the consequences of female genital mutilation to healthcare providers caring for women and girls living with female genital mutilation: a systematic review. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;136:65–71. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perron L, Senikas V, Burnett M, Davis V. Excision génitale féminine. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38:S348–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2016.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The National Health Service. Female genital mutilation (FGM) [Accessed February 2020]. Available from: www.nhs.uk/Conditions/female-genital-mutilation.

- 7.Pearce AJ, Bewley S. Medicalization of female genital mutilation. Harm reduction or unethical? Obstet Gynaecol Reprod Med. 2014;24:29–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ogrm.2013.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serour GI. Medicalization of female genital mutilation/cutting. Afr J Urol. 2013;19:145–9. doi: 10.1016/j.afju.2013.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morlin-Yron S. Cut in secret: the medicalization of FGM in Egypt. Feb 7, 2017. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://edition.cnn.com/2017/02/06/africa/africa-view-egypt-fgm/index.html.

- 10.Shell-Duncan B. The medicalization of female “circumcision”: harm reduction or promotion of a dangerous practice? Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1013–28. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Topping A, Carson M. FGM is banned but very much alive in the UK. Feb 6, 2014. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/feb/06/female-genital-mutilation-foreign-crime-common-uk.

- 12.Dorkenoo E, Morison L, Macfarlane A. A Statistical Study to Estimate the Prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation in England and Wales: Summary Report. London: Foundation for Women’s Health, Research and Development; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elchalal U, Ben-Ami B, Brzezinski A. Female circumcision: the peril remains. BJU Int. 1999;83:103–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biglu MH, Farnam A, Abotalebi P, Biglu S, Ghavami M. Effect of female genital mutilation/cutting on sexual functions. Sex Reprod Health. 2016;10:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazi T. Female genital mutilation: the role of medical professional organizations. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:537–41. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uddin Jurnalis, Duarsa ABS, Zuhroni H, et al., editors. Female circumcision: a social, cultural, health and religious perspectives. Jakarta: Yarsi University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on the management of health complications from female genital mutilation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishai D, Bonnenfant YT, Darwish M, Adam T, Bathija H, Johansen E, et al. Estimating the obstetric costs of female genital mutilation in six African countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:281–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.064808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wikimedia Commons. FGC types. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FGC_Types.jpg.

- 20.World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation: an overview. 1998. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42042.

- 21.WHO study group on female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome. Banks E, Meirik O, Farley T, Akande O, Bathija H, et al. Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet. 2006;367:1835–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Eliminating female genital mutilation: an interagency statement. UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCHR, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO; 2008. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/files/Interagency_Statement_on_Eliminating_FGM.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Refaei M, Aghababaei S, Pourreza A, Masoumi SZ. Socioeconomic and reproductive health outcomes of female genital mutilation. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19:805–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmes V, Farrington R, Mulongo P. Educating about female genital mutilation. Educ Prim Care. 2017;28:3–6. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2016.1245589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogt S, Mohmmed Zaid NA, El Fadil Ahmed H, Fehr E, Efferson C. Changing cultural attitudes towards female genital cutting. Nature. 2016;538:506–9. doi: 10.1038/nature20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdulcadir J, Rodriguez MI, Say L. Research gaps in the care of women with female genital mutilation: an analysis. BJOG. 2015;122:294–303. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yount KM, Carrera JS. Female genital cutting and reproductive experience in Minya, Egypt. Med Anthropol Q. 2006;20:182–211. doi: 10.1525/maq.2006.20.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation. 2020. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation.

- 29.Clarke E. Female genital mutilation: a urology focus. Br J Nurs. 2016;25:1022–8. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2016.25.18.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Eliminating female genital mutilation: an interagency statement. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. A systematic review of the health complications of female genital mutilation including sequelae in childbirth. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larsen U, Okonofua FE. Female circumcision and obstetric complications. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;77:255–65. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(02)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeplin PH. Clitoral hood reduction. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36:NP231. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunter JG. Labia minora, labia majora, and clitoral hood alteration: experience-based recommendations. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36:71–9. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjv092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Placik OJ, Arkins JP. A prospective evaluation of female external genitalia sensitivity to pressure following labia minora reduction and clitoral hood reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:442e–52e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rathmann WG. Female circumcision: indications and a new technique. 1959. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: http://www.noharmm.org/femcirctech.htm. [PubMed]

- 37.Triana L, Robledo AM. Aesthetic surgery of female external genitalia. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35:165–177. doi: 10.1093/asj/sju020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Economist. Odd bedfellows; new rows about circumcision unite unlikely friends and foes. 2012. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://www.economist.com/node/21562905/comments?page=5.

- 39.Thabet SM, Thabet AS. Defective sexuality and female circumcision: the cause and the possible management. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2003;29:12–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1341-8076.2003.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. (in Turkish; Biyomedikal Etik Prensipleri; translated by Temel MK) Istanbul: BETIM; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization. Management of Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Postpartum Period in the Presence of Female Genital Mutilation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winkel E. A muslim perspective on female circumcision, Women Health. 1995;23:1–7. doi: 10.1300/j013v23n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoosen F. The practice of female circumcision in African and Muslim Societies. Durban: IMASA Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.El-Ahl A. A small revolution in Cairo: theologians battle female circumcision. Dec 6, 2006. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://www.spiegel.de/international/spiegel/a-small-revolution-in-cairo-theologians-battle-female-circumcision-a-452790.html.

- 45.Menka E. Islam does not support female circumcision - Expert. Mar 16, 2005. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Islam-does-not-support-female-circumcision-Expert-77396.

- 46.Karaman H. No circumcision for girls. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: www.hayrettinkaraman.net/makale/0621.html.

- 47.News BBC. Call to end female circumcision. 2006. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/6176340.stm.

- 48.Cairo. Muslim scholars rule female circumcision un-Islamic. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://www.theage.com.au/world/muslim-scholars-rule-female-circumcision-un-islamic-20061124-ge3na6.html.

- 49.Islam Online Archive. Circumcision: juristic, medical & social perspectives. [Accessed February, 2020]. Available from: https://archive.islamonline.net/?p=5317.