Abstract

Astrocytes exist throughout the CNS and affect neural circuits and behavior through intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Studying the function(s) of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling has proven difficult because of the paucity of tools to achieve selective attenuation. Based on recent studies, we generated and used male and female knock-in mice for Cre-dependent expression of mCherry-tagged hPMCA2w/b to attenuate astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in genetically defined cells in vivo (CalExflox mice for Calcium Extrusion). We characterized CalExflox mice following local AAV-Cre microinjections into the striatum and found reduced astrocyte Ca2+ signaling (∼90%) accompanied with repetitive self-grooming behavior. We also crossed CalExflox mice to astrocyte-specific Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice to achieve inducible global CNS-wide Ca2+ signaling attenuation. Within 6 d of induction in the bigenic mice, we observed significantly altered ambulation in the open field, disrupted motor coordination and gait, and premature lethality. Furthermore, with histologic, imaging, and transcriptomic analyses, we identified cellular and molecular alterations in the cerebellum following mCherry-tagged hPMCA2w/b expression. Our data show that expression of mCherry-tagged hPMCA2w/b with CalExflox mice throughout the CNS resulted in substantial attenuation of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling and significant behavioral alterations in adult mice. We interpreted these findings candidly in relation to the ability of CalEx to attenuate astrocyte Ca2+ signaling, with regards to additional mechanistic interpretations of the data, and their relation to past studies that reduced astrocyte Ca2+ signaling throughout the CNS. The data and resources provide complementary ways to interrogate the function(s) of astrocytes in multiple experimental scenarios.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Astrocytes represent a significant fraction of all brain cells and tile the entire central nervous system. Unlike neurons, astrocytes lack propagated electrical signals. Instead, astrocytes are proposed to use diverse and dynamic intracellular Ca2+ signals to communicate with other cells. An open question concerns if and how astrocyte Ca2+ signaling regulates behavior in adult mice. We approached this problem by generating a new transgenic mouse line to achieve inducible astrocyte Ca2+ signaling attenuation in vivo. We report our data with this mouse line and we interpret the findings candidly in relation to past studies and within the framework of different mechanistic interpretations.

Keywords: Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2, astrocyte, calcium, striatum

Introduction

Important progress has been made exploring astrocytes, especially their contributions to synapse formation and removal (Allen and Lyons, 2018). However, the field lacks comprehensive understanding of how astrocytes perform multiple functions to regulate the cells they contact, and how they influence neural circuits and behavior. One hindrance has been the lack of tools with which to attenuate or activate astrocyte signaling within the adult CNS (Hirbec et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020a).

Astrocytes display intracellular Ca2+ signaling dynamics, which are well documented and proposed to underlie physiological functions (Howarth, 2014; Volterra et al., 2014; Oliveira et al., 2015; Bazargani and Attwell, 2016; Shigetomi et al., 2016; Verkhratsky and Nedergaard, 2018; Yu et al., 2020a; Nagai et al., 2021). The question of whether astrocyte Ca2+ signals are causal for changes in neural circuit function and behavior in adult mice is beginning to be directly explored. Such experiments have become possible because of reliable methods to target astrocytes genetically (Yu et al., 2020a) and to monitor astrocyte Ca2+ signaling with genetically encoded calcium indicators (Hires et al., 2008; Russell, 2011; Volterra et al., 2014; Nimmerjahn and Bergles, 2015; Shigetomi et al., 2016). These advances have, in turn, necessitated the use of methods to both increase and attenuate Ca2+ signals within astrocytes in vivo and to explore the consequences. A variety of methods now exist to increase astrocyte Ca2+ signaling, including LiGluR, channelrhodopsin-based effectors, melanopsin, optoXRs, and designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (Hirbec et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020a). In contrast, despite progress with IP3 receptor type 2 deletion mice (IP3R2−/−) and IP3 sponges (Petravicz et al., 2008; Agulhon et al., 2010; Xie et al., 2010), the development of approaches to efficiently attenuate astrocyte Ca2+ signaling has lagged behind, probably because of the diverse nature of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling. Furthermore, although the use of IP3R2−/− mice initially furnished little evidence for a role for astrocyte IP3-mediated Ca2+ signals in regulating behavior, subsequent studies have found that such mice display altered responses in a variety of settings (see Fiacco and McCarthy, 2018; Savtchouk and Volterra, 2018). The realization that IP3R2−/− mice show astrocyte Ca2+ signaling that was undetected in earlier studies has also emphasized the need for additional methods to attenuate astrocyte Ca2+ signaling to explore physiological functions (Di Castro et al., 2011; Srinivasan et al., 2015; Rungta et al., 2016; Agarwal et al., 2017).

Recently, we developed a genetic approach to attenuate endogenous astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in vivo regardless of the Ca2+ source (Yu et al., 2018). A human plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase pump (type 2, variant w/b; hPMCA2w/b) that constitutively extrudes Ca2+ from cells and which is not endogenously expressed in astrocytes was used. GfaABC1D adeno-associated virus 2/5 (AAV2/5)-mediated overexpression of hPMCA2w/b on the plasma membrane of astrocytes in the striatum reduced spontaneous and G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)-mediated Ca2+ signals, resulting in enhanced repetitive behaviors (Yu et al., 2018). We termed the hPMCA2w/b approach CalEx, a mnemonic for Ca2+ extrusion. To further improve CalEx, we developed knock-in mice at the Rosa26 locus (CalExflox mice) to potentially enable both circuit-specific and global CNS-wide Ca2+ attenuation in vivo. hPMCA2w/b expression was controlled by Cre expression and resulted in more rapid and greater Ca2+ signaling attenuation than previously possible (Yu et al., 2018). We employed CalExflox mice to explore the consequences of CNS-wide attenuation of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling, and based on the empirical data we performed gene expression analyses to report likely molecular mechanisms. Our studies show that CalExflox mice can be used to efficiently attenuate astrocyte Ca2+ signaling. Thus, we provide well-characterized resources to broadly explore astrocyte signaling in vivo in multiple experimental scenarios. We also carefully consider mechanistic interpretations of our findings in relation to past studies on the topic and discuss future uses, caveats, and further developments.

Materials and Methods

Material availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available on request. Line 1 CalExflox mice have been deposited at JAX with genetic descriptor Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(CAG-mCherry-hPMCA2w/b)Khakh (Stock No. 035252). RNA-seq data have been deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; #GSE164235).

Data availability

All data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Mouse models

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Chancellor's Animal Research Committee at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Male and female mice aged between 6 and 12 weeks old were used in this study. Mice were housed in the vivarium managed by the Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine at UCLA with a 12/12 h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. Wild-type C57BL/6NTac and Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice were generated from in house breeding colonies. CalExflox mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6NTac for more than eight generations. Heterozygous CalExflox mice were crossed with Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice (Srinivasan et al., 2016) to generate bigenic mice carrying both alleles.

Generation of CalExflox mice at the Rosa26 locus

The Rosa26 targeting plasmid was modified from the Ai39 plasmid (Addgene #34884) to contain transgene mCherry-hPMCA2w/b and the knock-in mice were generated using well-established methods (Srinivasan et al., 2016). The CalExflox mice contain a CMV-IE enhancer/chicken β-actin/rabbit β-globin hybrid promoter (CAG) promoter, followed by a loxP-3×SV40pA-loxP cassette and the mCherry-hPMCA2w/b cDNA at the Rosa26 locus. Briefly, CalEx transgene was amplified by PCR from the pZac2.1-GfaABC1D-mCherry-hPMCA2w/b plasmid (Addgene #111568) and subcloned between MluI sites in the Ai39 plasmid to create the CalEx Rosa26 targeting plasmid. All cloning was performed using Stbl2 cells (Invitrogen) that were propagated at 30°C to prevent recombination. Sequences of the targeting construct were confirmed with diagnostic restriction digests, PCR amplification and sequencing of the ampicillin and neomycin resistance cassette as well as the 5′ and 3′ homology arms. For electroporation of embryonic stem (ES) cells, the CalEx Rosa26 targeting plasmid was linearized with AclI, which cuts at two sites within the ampicillin resistance cassette, and then purified with a concentration of 1015 ng/µl. Linearized plasmid DNA was electroporated into C57BL/6 JM8.N4 ES cells and 288 clones were picked to expand in 96-well plates at the UC Davis Mouse Biology Program (MBP). Recombinant clones were then injected into blastocysts from BALB/cAnNTac donors. Chimeric animals were scored based on coat color and animals that showed > 50% chimerism were bred with wild-type mice to confirm germline transmission. Heterozygous CalExflox mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6NTac mice for more than eight generations, i.e., to ∼99.6% C57BL/6NTac. Both heterozygous and homozygous CalExflox mice are viable and fertile. All the results presented in this study were generated with heterozygous CalExflox mice. Genotypes of CalExflox mice were performed by PCR with genomic DNA from either the ear or tail biopsies. Wild-type allele was confirmed by forward primer 5′-CCTTTCTGGGAGTTCTCTGCTGC-3′; reverse primer 5′-GCGGATCACAAGCAATAATAACCTG-3′; giving a 332 bp amplicon. CalExflox allele was confirmed by forward primer 5′-CCTTTCTGGGAGTTCTCTGCTGC-3′; reverse primer 5′-CGTAAGTTATGTAACGCGGAACTCC-3′; giving a 217-bp amplicon.

Generation of CalExflox × Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 bigenic mice

To generate bigenic mice, heterozygous CalExflox mice were crossed with hemizygous Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice. Bigenic pups were identified by genotyping for CalEx insert at the ROSA26 locus (forward primer 5′-CCTTTCTGGGAGTTCTCTGCTGC-3′; reverse primer 5′-CGTAAGTTATGTAACGCGGAACTCC-3′) and Cre/ERT2 (forward primer 5′-AGACCAATCATCAGGATCTCTAGCC-3′; reverse primer 5′-CATGCAAGCTGGTGGCTGG-3′) in two separate PCR reactions for each pup. Bigenic mice used for experiments were heterozygous for CalEx at the ROSA26 locus and hemizygous for the Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 insert (CalExflox/wt; Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2). Three littermate control groups were included in all the experiments: (1) wild-type mice; (2) Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice; and (3) CalExflox/wt mice.

Tamoxifen administration

Tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648) was freshly prepared at a concentration of 25 mg/ml in corn oil and dissolved at 37°C with continuous agitation. As previously described (Srinivasan et al., 2016), to induce gene expression, tamoxifen was administered intraperitoneally at 75 mg/kg body weight for 1 d or five consecutive days, using a 1-ml syringe and a 25-G 5/8-inch needle (BD Biosciences).

Surgical procedure of in vivo microinjection

Surgical procedures for viral microinjections have been described previously (Shigetomi et al., 2013; Chai et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2018; Nagai et al., 2019). In brief, mice aged six to nine weeks old were anesthetized and placed onto a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga CA). Continuous anesthesia using isoflurane was carefully monitored and adjusted throughout the surgery. Mice were injected with buprenorphine (Buprenex; 0.1 mg/kg) subcutaneously before surgery. Scalp incisions were made and craniotomies (∼1 mm in diameter) were created using a high-speed drill (Henry Schein Medical Dental) for unilateral viral injections while two craniotomies were made above both parietal cortices for bilateral viral injections. Beveled glass pipettes (1B100-4; World Precision Instruments) filled with viruses were placed into the dorsal striatum (0.8 mm anterior to the bregma, 2.0 mm lateral to the midline, and 2.4 mm from the pial surface) or the hippocampal CA1 (2.0 mm posterior to the bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to the midline, and 1.6 mm from the pial surface) or the cerebellum (6.0 mm posterior to the bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to the midline, and 1.0 mm from the pial surface). AAVs were injected at 200 nl/min using a microinjection syringe pump (UMP3; World Precision Instruments). Glass pipettes were withdrawn after 10 min, and scalps were cleaned and sutured with sterile surgical sutures. Mice were allowed to recover in clean cages with food containing trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and water for 7 d. Subsequent histologic, imaging and behavioral experiments were performed 3–21 d after surgeries.

Viruses used in this study included: AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-Cre, AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-GCaMP6f, and AAV2/5 GfaABC1D-tdTomato. All of these have been previously characterized for the striatum at the ages used in this study (Tong et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2016; Chai et al., 2017; Octeau et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018; Nagai et al., 2019). Viruses were injected with a total volume of 0.2–0.5 µl per site to deliver ∼1010 genome copies into the dorsal striatum or the hippocampal CA1 or the cerebellum.

Brain slice preparation for Ca2+ imaging

Mice were transferred from the vivarium to the laboratory during the light cycle between 8 and 10 A.M. Brain slices were prepared 30 min to 1 h afterward and were used for experiments within 8 h of slicing (mostly within 6 h). Both male and female mice (8–11 weeks old) were anesthetized and decapitated approximately two to four weeks after AAV injection. Coronal slices (300 μm thick) of the striatum or sagittal slices (300 μm thick) of the cerebellum were prepared in ice-cold sucrose cutting solution (30 mm NaCl, 4.5 mm KCl, 1.2 mm NaH2PO4, 26 mm NaHCO3, 10 mm D-glucose, 194 mm sucrose, and 1 mm MgCl2) using a vibratome (DSK Microslicer; Ted Pella). Slices were then incubated in artificial ACF (ACSF; 124 mm NaCl, 4.5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1.2 mm NaH2PO4, 26 mm NaHCO3, 10 mm D-glucose, and 2.0 mm CaCl2) for 30 min at 32°C and then 1 h at room temperature before recording. All the solutions were oxygenated with 95% O2/5% CO2.

Intracellular Ca2+ imaging of astrocytes and analysis

Ca2+ imaging in brain slices was performed using a Scientifica two-photon laser-scanning microscope equipped with a MaiTai laser (Spectra-Physics). To image GCaMP6f signals, the laser was tuned at 920-nm wavelength. The laser power measured at the sample was <30 mW with a 40× water-immersion objective lens (Olympus). Striatal astrocytes or Bergmann glia located at least 40 µm from the slice surface were selected for imaging. Images were acquired at one frame per second using SciScan software (Scientifica). Brain slices were maintained in ACSF (124 mm NaCl, 4.5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1.2 mm NaH2PO4, 26 mm NaHCO3, 10 mm D-glucose, and 2.0 mm CaCl2) through a perfusion system. Phenylephrine (PE; 10 μm) or ATP (100 μm) was bath-applied for 2 min to activate GPCR-mediated Ca2+ signals. 0.25 μm TTX was present throughout the experiment.

For region of interest (ROI)-based analysis, the somata, major branches and territories of striatal astrocytes and the somata of Bergmann glia were manually demarcated and Ca2+ signals recorded in a single optical plane were measured by plotting the intensity of regions of interest over time. Slow drifts in cell position (∼2–5 µm) were corrected with a custom Plugin in NIH ImageJ. A signal was declared as a Ca2+ transient if it exceeded the baseline by greater than twice the baseline noise (SD). Ca2+ signals were processed in ImageJ and presented as the relative change in fluorescence (ΔF/F). Peak amplitude, half-width, frequency and integrated areas of Ca2+ signals were analyzed in OriginPro 2016 (OriginLab).

For event-based analysis, 1-min recording of spontaneous Ca2+ signals was de noised in ImageJ and then analyzed with AQuA in MATLAB (Wang et al., 2019) to detect individual Ca2+ events. The AQuA version used was downloaded in December 2019 from Github. Parameters were adjusted for cytosolic GCaMP6f ex vivo experiments.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and analysis

Both male and female mice (6–12 weeks old) were transcardially perfused with 0.1 m PBS followed by 10% formalin. Brains were dissected out and postfixed in 10% formalin for several hours and then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose (0.1 m PBS). Serial 40-µm sections were collected and incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: mouse anti-S100β (1:1000; Sigma, S2532), mouse anti-NeuN (1:1000; Millipore, MAB377), and rabbit anti-RFP (1:1000; Rockland, 600-401-379). The sections were then washed three times in 0.1 m PBS for 10 min each before incubation at room temperature for 2 h with secondary antibodies diluted in 0.1 m PBS. Alexa-conjugated (ThermoFisher Scientific) secondary antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilution. Fluorescent images were acquired with a 40× oil-immersion objective lens (NA 1.3) under a laser-scanning confocal microscope (FV1000; Olympus). Whole brain images were acquired with a 10× air objective lens (NA 0.3) on a confocal laser-scanning microscope (C2; Nikon). Laser settings were kept the same within each experiment. Images represent maximum intensity projections of optical sections with a step size of 1.0 μm. Images were processed with ImageJ. Cell counting was done on maximum intensity projections using the Cell Counter plugin; only cells with soma completely within the ROI were counted.

Behavioral tests

Behavioral tests were performed during the light cycle between 12 and 6 P.M. Both male and female mice (6–12 weeks old) were used in behavioral tests. All the experimental mice were transferred to the behavior testing room at least 30 min before the tests to acclimatize to the environment and to reduce stress. Temperature and humidity of the experimental rooms were kept at 23 ± 2°C and 55 ± 5%, respectively. Background noise (65 ± 2 dB) was generated by a white noise generator (San Diego Instruments).

Open field test

The open field chamber consisted of a square arena (28.7 × 30 cm) enclosed by walls made of translucent polyethylene (15 cm tall). The brightness of the experimental room was kept <10 lux. Locomotor activity of mice at 6–12 weeks old was then recorded for 10 min using an infrared camera located above the open field chamber. The open field behaviors were analyzed with an automated video tracking software ANY-maze from Stoelting.

Self-grooming behavior

Mice were placed individually into plastic cylinders (15 cm in diameter and 35 cm tall) and allowed to habituate for 20 min. The brightness of the experimental room was kept <10 lux. Self-grooming behavior was recorded for 10 min. A timer was used to assess the cumulative time spent in self-grooming behavior, which included paw licking, unilateral and bilateral strokes around the nose, mouth, and face, paw movement over the head and behind ears, body fur licking, body scratching with hind paws, tail licking, and genital cleaning. The number of self-grooming bouts was also counted. Separate grooming bouts were considered when the pause was >5 s or behaviors other than self-grooming occurred. Self-grooming microstructure was not assessed.

Rotarod test

Mice were held by the tails and placed on the rod (3 cm diameter) of a single lane rotarod apparatus (ENV-577 M, Med Associates Inc.), facing away from the direction of rotation. The rotarod was set with a start speed of 4 rpm. Acceleration started 10 s later and was set to 20 rpm/min with a maximum speed 40 rpm. Each mouse received two trials 30 min apart and the latency to fall was recorded for each trial. The average latency to fall was used as a measurement for motor coordination (Deacon, 2013).

Footprint test

A 1-m-long runway (8 cm wide) was lined with paper. Each mouse with hind paws painted with non-toxic ink was placed at an open end of the runway and allowed to walk to the other end with a darkened box. For the gait analysis, stride length and width were measured and averaged for both left and right hindlimbs over five steps.

Cerebellar RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and analysis

To perform bulk RNA-seq of the Cb, 5 d after the single dose tamoxifen injection (75 mg/kg body weight), cerebella from CalExflox/wt and bigenic mice were dissected out and frozen in a tissue transition solution (Invitrogen, #AM7030) overnight. The tissues were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer and the cerebellar RNA was extracted using a mirVana miRNA isolation kit following the manufacturer's instruction (Invitrogen, #AM1560). RNA concentration and quality were assessed with Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. RNA samples with RNA integrity number (RIN) >7 were used for multiplexed library preparation with Nugen Ovation RNA-Seq System V2. All samples were multiplexed into a single pool to avoid batch effects (Auer and Doerge, 2010), and sequencing was performed on Illumina NextSeq 4000 for 2 × 75 yielding at least 45 million reads per sample. De-multiplexing was performed with Illumina Bcl2fastq2 v 2.17 program. Reads were aligned to the mouse mm10 reference genome using the STAR spliced read aligner (Dobin et al., 2013) with default parameters and fragment counts were derived using HTS-seq program. Approximately 70% of the reads mapped uniquely to the mouse genome and were used for subsequent analyses. Differential gene expression analysis was performed with Bioconductor packages edgeR (Robinson et al., 2010) with false discovery rate (FDR) threshold < 0.05 (http://www.bioconductor.org). Lowly expressed genes that had CPM > 3 in at least four samples were filtered out. In addition, we have applied FPKM > 1 as an additional threshold to exclude low expression genes for the analyses of differentially expression gene (DEG) numbers and canonical pathways. This value was chosen based on previously published literature (Hebenstreit et al., 2011; Uhlen et al., 2017). For the top 50 gene list, we used FPKM > 5 as a threshold to select genes with higher expression levels. Significantly associated canonical pathways (p < 0.05) were identified by ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) using DEGs with thresholds FPKM > 1 and FDR < 0.05. The RNA-seq data have been deposited within the GEO repository (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) with accession number GSE164235. The complete list of DEGs is provided in Extended Data Table 7-1.

Supplementary Table 7-1. Download Table 7-1, XLSX file (829.8KB, xlsx) .

The cerebellar scRNA-seq data were downloaded from Linnarsson lab's database (www.mousebrain.org) and analysis was performed with the Scanpy package in Python (Wolf et al., 2018). Cerebellar cells with >300 genes and genes expressed in more than three cells were used for the subsequent analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the expression data matrix using Arpack wrapper function in the Scanpy package (Wolf et al., 2018). PCs 1–50 were used for generating t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plots. Eleven transcriptomic clusters were identified from total 11,063 cerebellar cells with a Louvain-Jaccard graph clustering algorithm with resolution set to 0.1 and were then annotated based on the expression of cell lineage marker genes (Saunders et al., 2018).

Experimental design and statistical analyses

For each experiment, multiple cohorts of age-matched mice with mixed genders were used to avoid batch effects. Comparisons were made as following: CalExflox/wt mice with Cre AAV versus CalExflox/wt mice with no AAV (Fig. 1); CalExflox/wt mice with Cre AAV versus CalExflox/wt mice with control AAV (Figs. 2, 6); bigenic mice with tamoxifen injection (multiple doses and single dose) versus littermate control mice including wild-type mice, Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice, and CalExflox/wt mice with tamoxifen injection (Figs. 3–5); bigenic mice with single dose tamoxifen injection versus littermate CalExflox/wt mice with single dose tamoxifen injection (Fig. 7). The genotypes of mice were blind to the experimenters, however, bigenic mice developed observable behavioral phenotypes several days after tamoxifen injection, which made blinding the experiments difficult. Sample sizes were based on similar previously published work (Chai et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2018, 2020b; Nagai et al., 2019).

Figure 1.

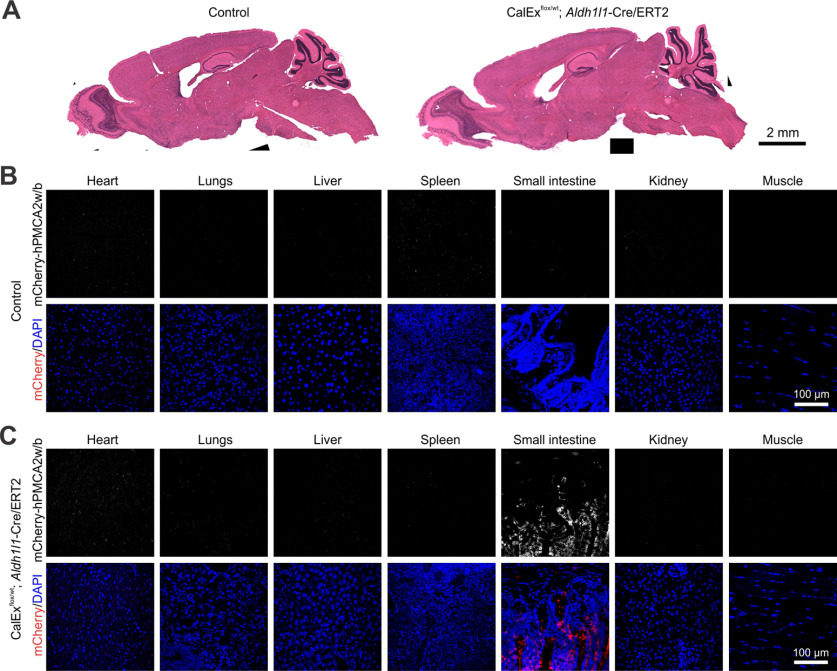

Generation of CalExflox mice to express mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in astrocytes for Ca2+ signaling attenuation. A, Schematic for human plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase isoform 2 splice variant w/b (hPMCA2w/b) expression on the plasma membrane of astrocytes to attenuate Ca2+-dependent signaling. B, Schematic of the generation and characterization of CalExflox mice. Left, CalExflox mice contain a CAG promoter, followed by a loxP-3×SV40pA-loxP cassette, and the mCherry-tagged hPMCA2w/b transgene (Yu et al., 2018) at the endogenous Rosa26 locus. Right, The expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in astrocytes of adult mice was examined with two strategies: (1) an AAV2/5 encoding a Cre recombinase under an astrocyte-specific promoter GfaABC1D was microinjected into a specific brain region; and (2) CalExflox mice were crossed with Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice to generate bigenic mice carrying both alleles (CalExflox/wt; Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice). Upon the injection of tamoxifen, mCherry-hPMCA2w/b was expressed across the entire mouse brain. C, Representative IHC images from the dorsolateral striatum (top panels) and the hippocampal CA1 (bottom panels) of CalExflox mice showing no leaky expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in the absence of Cre recombinase. D, IHC images showing robust expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in the dorsolateral striatum (top panels) and the hippocampal CA1 (bottom panels) of CalExflox mice one week after the injection of AAV2/5-GfaABC1D-Cre. E, F, Higher-magnification IHC images showing co-localization of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b with astrocyte marker S100β in the dorsolateral striatum (E) and the hippocampal CA1 stratum radiatum (F). G, H, Timeline of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in the dorsolateral striatum (G) and the hippocampal CA1 stratum radiatum (H) after AAV2/5-GfaABC1D-Cre injection. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. In some cases, the SEM symbol is smaller than the symbol for the mean; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Figure 2.

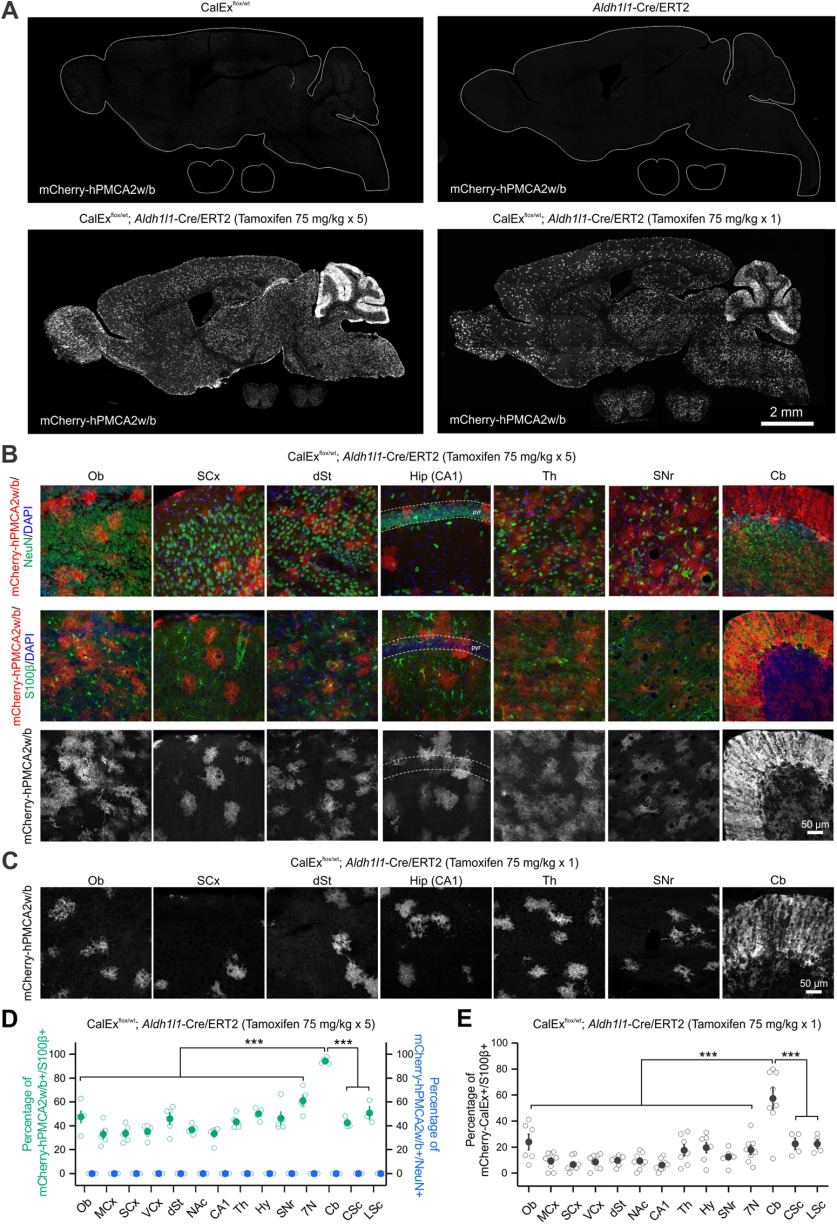

Attenuation of spontaneous and GPCR-mediated Ca2+ signaling in striatal astrocytes with CalExflox mice. A, Z-stack images of two-photon Ca2+ imaging of GCaMP6f-expressing striatal astrocytes from CalExflox mice microinjected with control (top) or Cre (bottom) AAVs, with the soma, major branch and territory outlined. B, Representative traces of spontaneous Ca2+ signals in the somata, major branches and territories of striatal astrocytes from CalExflox mice with control (top) or Cre (bottom) AAVs. C, Frequency, peak amplitude and half-width of spontaneous Ca2+ signals in somata, major branches and territories of striatal astrocytes. D, Z-stack images of 10-s Ca2+ recording from striatal astrocytes of CalExflox mice with control or Cre AAVs. Spontaneous Ca2+ events detected by AQuA were labeled in different colors. E, Average numbers of Ca2+ events, distribution of event area sizes and spatial density of co-occurred Ca2+ events, detected by AQuA from 1-min recording. F, Kymographs of Ca2+ responses evoked by PE (10 μm) in the somata of striatal astrocytes from CalExflox mice with control or Cre AAVs. G, Quantification of PE-induced Ca2+ responses as integrated areas during baseline, PE application, and washout. H, Kymographs of Ca2+ responses evoked by ATP (100 μm) in the somata of striatal astrocytes from CalExflox mice with control or Cre AAVs. I, Quantification of ATP-induced Ca2+ responses as integrated areas during baseline, ATP application, and washout. J, Example images showing self-grooming behavior. K, Behavioral traces of CalExflox mice with control or Cre AAVs showing self-grooming and non-grooming episodes over 10 min. L, The duration of self-grooming (left) and the number of self-grooming bouts (right) of CalExflox mice with control or Cre AAVs. Average data are shown as mean ± SEM; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n.s. p > 0.05, n/a not applicable because of unequal sample sizes.

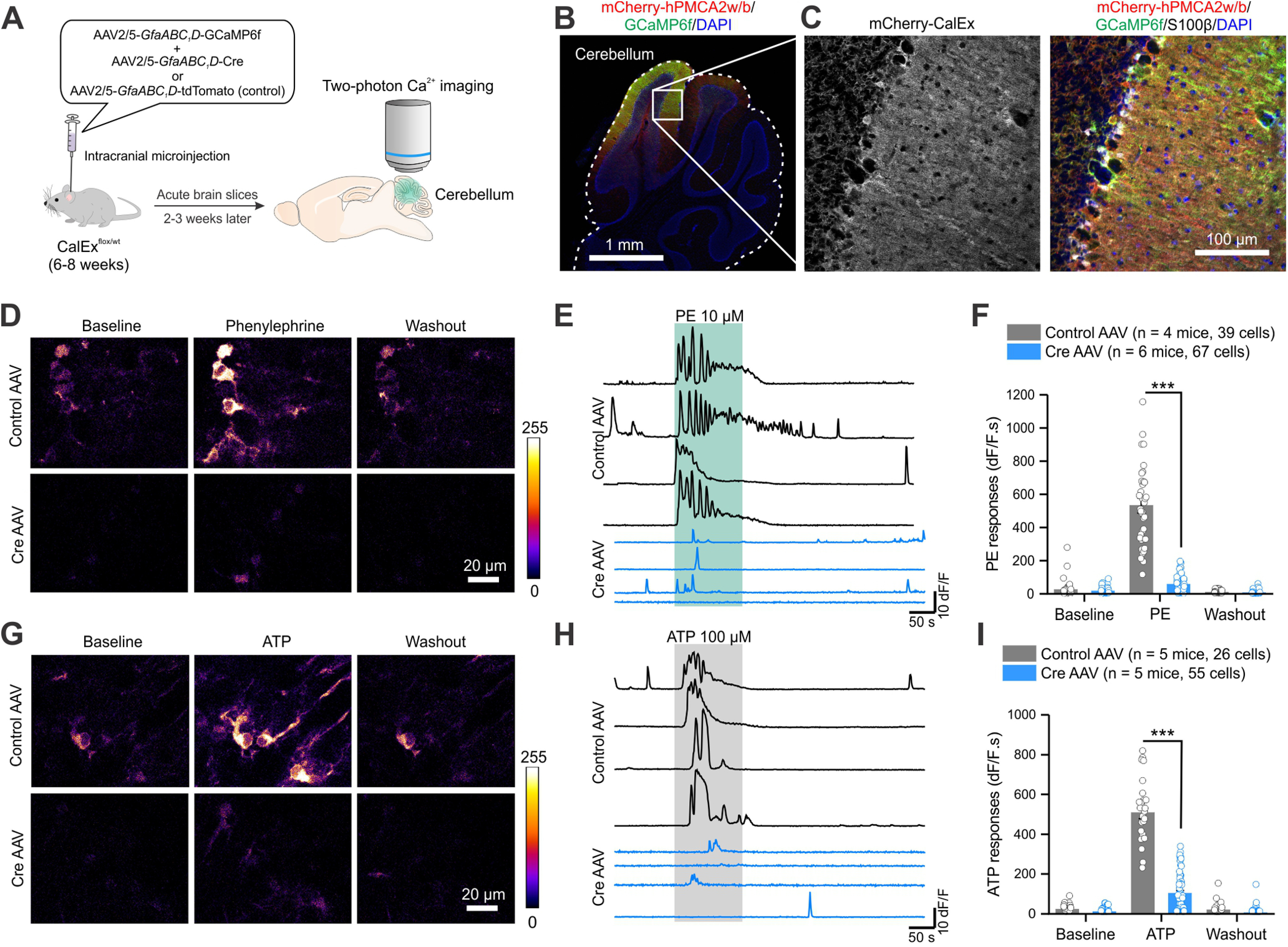

Figure 6.

Attenuation of GPCR-mediated Ca2+ signaling in Bergmann glia with CalExflox mice. A, Schematic of experimental design. To image Ca2+ signals in Bergmann glia, CalExflox mice received microinjections of AAV2/5-GfaABC1D-GCaMP6f together with control or Cre AAVs. Two-photon Ca2+ imaging of GCaMP6f-expressing Bergmann glia was performed two to three weeks after the AAV injection. B, An IHC image of the entire cerebellum showing the expression of GCaMP6f and mCherry-hPMCA2w/b. C, Higher-magnification IHC images showing mCherry-hPMCA2w expression in Bergmann glia that was colocalized with GCaMP6f and S100β. D, Z-stack images of two-photon Ca2+ imaging of Bergmann glia from CalExflox mice microinjected with control (top) or Cre (bottom) AAVs during baseline, PE (10 μm) application, and washout. E, Representative traces of Ca2+ responses to PE in the somata of Bergmann glia from CalExflox mice with control (top) or Cre (bottom) AAVs. F, Quantification of PE-induced Ca2+ responses as integrated areas during baseline, PE application, and washout. G, Z-stack images of Bergmann glia from CalExflox mice microinjected with control (top) or Cre (bottom) AAVs during baseline, ATP (100 μm) application, and washout. H, Representative traces of Ca2+ responses to ATP in the somata of Bergmann glia from CalExflox mice with control (top) or Cre (bottom) AAVs. I, Quantification of ATP-induced Ca2+ responses as integrated areas during baseline, ATP application, and washout. Average data are shown as mean ± SEM; ***p < 0.001.

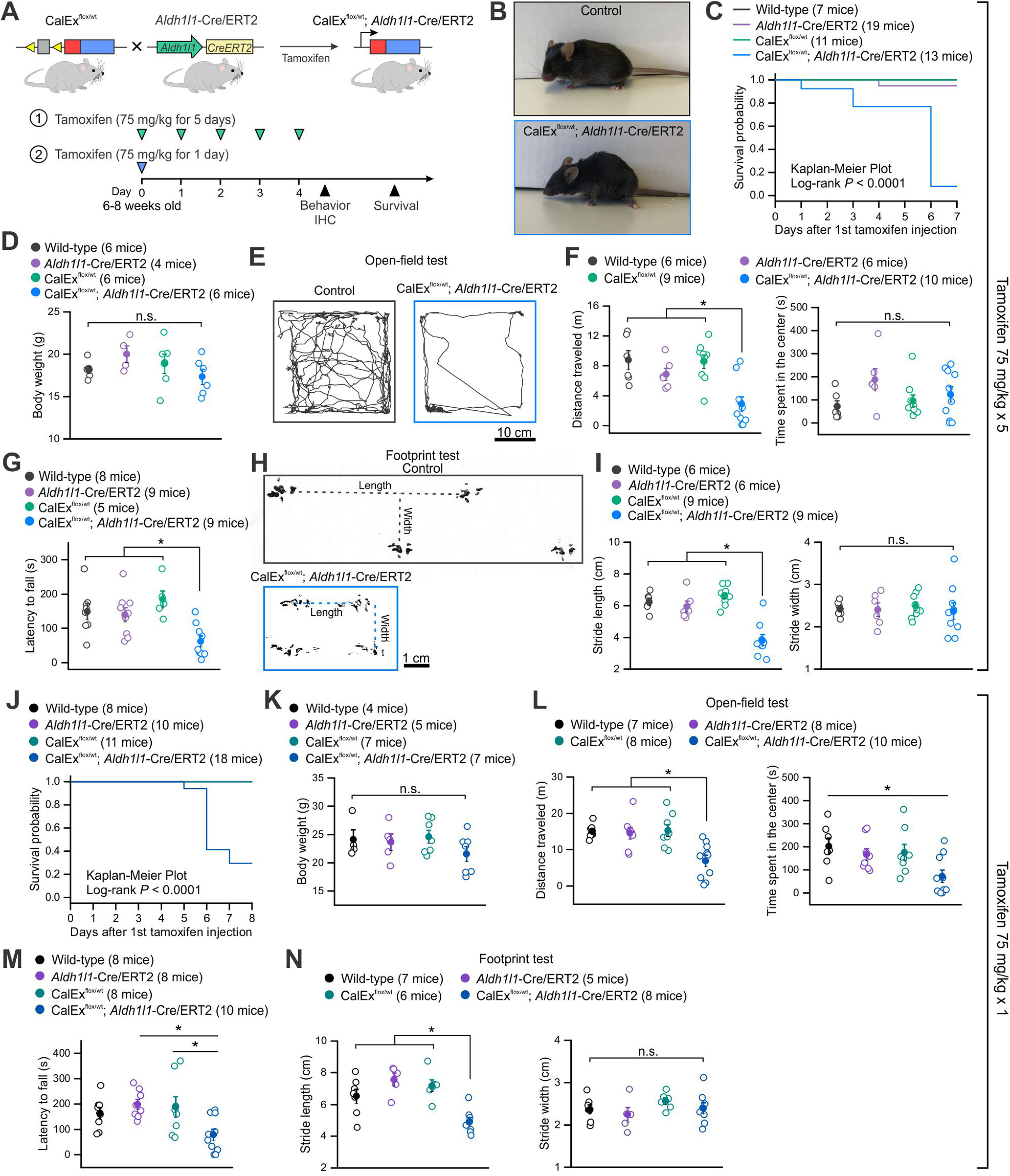

Figure 3.

Expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in adult CNS astrocytes in bigenic (CalExflox; Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2) mice results in strong behavioral phenotypes and premature lethality. A, Schematic of experimental design. CalExflox mice were crossed with Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice to generate bigenic (CalExflox/wt; Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2) mice, which received tamoxifen intraperitoneally at 75 mg/kg body weight for 1 d or five consecutive days. The first dose of tamoxifen was administered on day 0, behavioral and IHC assessments were performed on day 4. Behavioral results for multiple doses of tamoxifen injection (75 mg/kg × 5 d) are summarized in panels B–I and results for single dose tamoxifen injection (75 mg/kg × 1 d) are summarized in panels J–N. B, Images of a control mouse and a bigenic mouse after the last dose of tamoxifen injection. C, Survival probability of littermate control (wild-type, CalExflox/wt and Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2) and bigenic mice with multiple doses of tamoxifen. D, Body weight of control and bigenic mice was comparable. E, Representative track traces of locomotor activity in open-field tests of control and bigenic mice over 10 min. F, Travel distance (left) and time spent in the center (right) of open-field activity. Bigenic mice traveled significantly less distance compared with control mice. G, Average latency to fall in a rotarod test of control and bigenic mice. H, Representative footprint tracks of control and bigenic mice. Dotted lines indicate stride lengths and widths. I, Average footprint stride length and width of control and bigenic mice. J, Survival probability of littermate control and bigenic mice with single dose tamoxifen. K, Body weight of control and bigenic mice was similar. L, Bigenic mice traveled significantly less distance (left) and spent less time in the center of the open-filed chamber (right) compared with control mice. M, Average latency to fall in a rotarod test of control and bigenic mice. N, Average footprint stride length and width of control and bigenic mice. Average data are shown as mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05, n.s. p > 0.05. The p values were from one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test.

Figure 5.

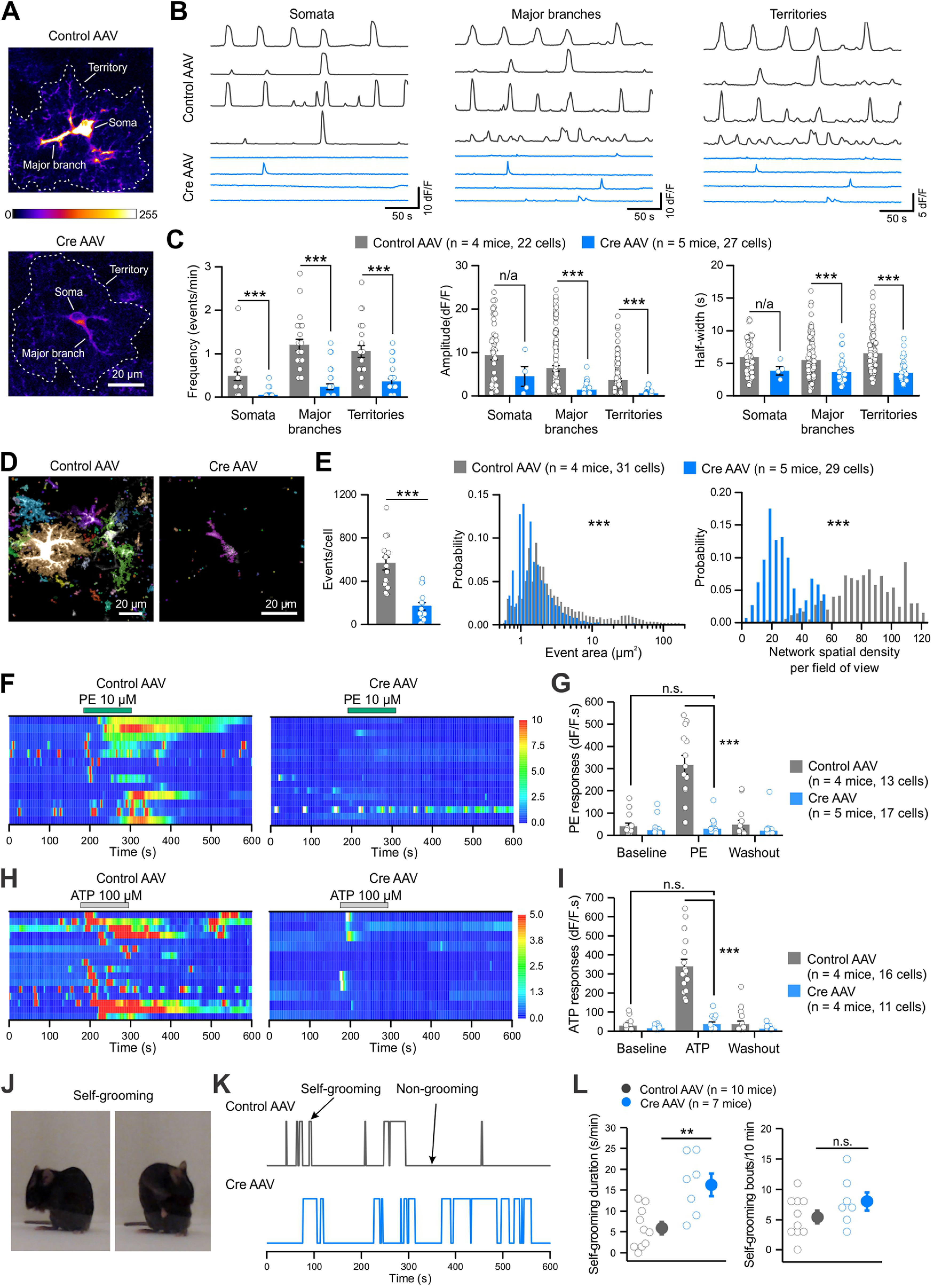

Expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in peripheral organs of bigenic mice with the multiple dose tamoxifen protocol. A, Hematoxylin and eosin staining showing that the gross histology of the brain from bigenic (CalExflox/wt; Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2) mice was not altered. B, C, IHC images showing mCherry-hMPCA2w/b expression from seven peripheral organs including the heart, lungs, liver, spleen, small intestine, kidney, and muscle from the control (B) and bigenic (C) mice. mCherry-CalEx expression was detected in the small intestine but not in other organs.

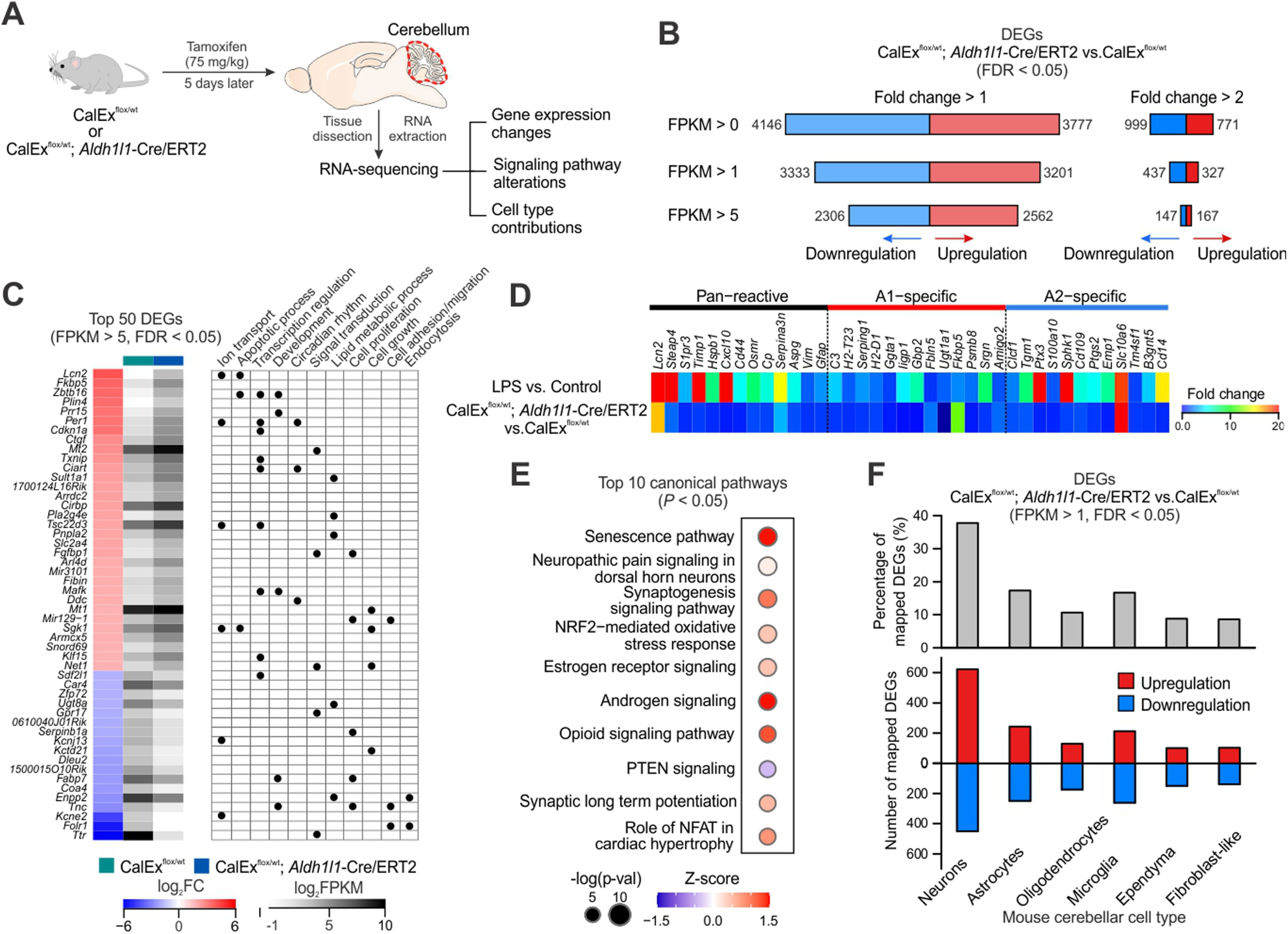

Figure 7.

Cerebellar RNA-seq reveals transcriptomic alterations induced by mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in bigenic mice. A, Schematic of experimental design. Both CalExflox mice (control) and bigenic mice received a single dose tamoxifen injection (75 mg/kg × 1 d) and cerebellar tissues were dissected out and processed for RNA-seq 5 d later. B, Numbers of DEGs (analyzed by edgeR, FDR < 0.05) that were upregulated and downregulated under different thresholds (FPKM > 0, 1 and 5; fold change > 1 and 2). C, left, Top 50 DEGs (FPKM > 5, FDR < 0.05) by mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in the cerebella of bigenic mice, ranked by fold change when comparing with CalExflox mice. Right, Summary table of selected gene ontology terms (biological processes) that are associated with each DEG. D, Heat map showing relative expression levels of 38 known reactive astrocyte markers including proposed pan-reactive, A1-specific and A2-specific genes in bigenic mice compared with control mice. E, Top 10 altered canonical pathways in cerebellar RNA-seq from bigenic mice. Sizes of dots represent log-transformed p value and colors indicate either pathway activation (red) or inhibition (blue) based on z scores. F, top, Percentage of DEGs in bigenic mice (FPKM > 1, FDR < 0.05) that were mapped onto mouse cerebellar scRNA-seq data, based on the top 1000 cell type marker genes for the six major cell types. Bottom, Numbers of mapped DEGs onto different cerebellar cell types that were upregulated and downregulated. List of DEGs identified in the cerebellar RNA-seq of bigenic mice are listed in Extended Data Table 7-1.

The results of statistical comparisons, n numbers and exact p values are provided in the text, with the exception of p < 0.0001. When the average data are reported in the text, the statistics are reported there. Statistical tests were performed in OriginPro 2016. Summary data are presented as mean ± SEM along with the individual data points. Note that in some of the graphs the bars representing the SEM are smaller than the symbols used to represent the mean. For each set of data to be compared we determined whether the data were normally distributed or not with a Shapiro–Wilk test. If the data were normally distributed, we used parametric tests. If the data were not normally distributed, we used non-parametric tests. Two-tailed Student's t tests with Welch correction and two-tailed Mann–Whitney tests were used for most statistical analyses. Comparisons of datasets with more than two groups or conditions were calculated with one-way ANOVA tests followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests. Survival curves were analyzed with Kaplan–Meier estimate. Significance was declared at p < 0.05. In the figures, p values were stated by asterisk(s) for simplification: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; n.s., not significant. N is defined as the numbers of cells, sections or mice throughout on a case-by-case basis; the unit of analysis is stated in each figure panel, in the text or figure legend.

Results

There are two main sections to this study. In part one, we describe the generation of CalExflox mice, and their functional validation in the striatum (Figs. 1, 2). In part two, we used CalExflox mice to achieve CNS-wide attenuation of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling and explored the impact on mouse behavior and transcriptomic signatures of a relevant brain area that was suggested by our empirical observations, the cerebellum (Figs. 3–7). We also interpret the underlying changes following CalEx expression as a Ca2+ signaling attenuation tool using three descriptive models (Fig. 8). The RNA-seq data have been deposited within the GEO repository (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) with accession number GSE164235. The complete list of DEGs is provided in Extended Data Table 7-1.

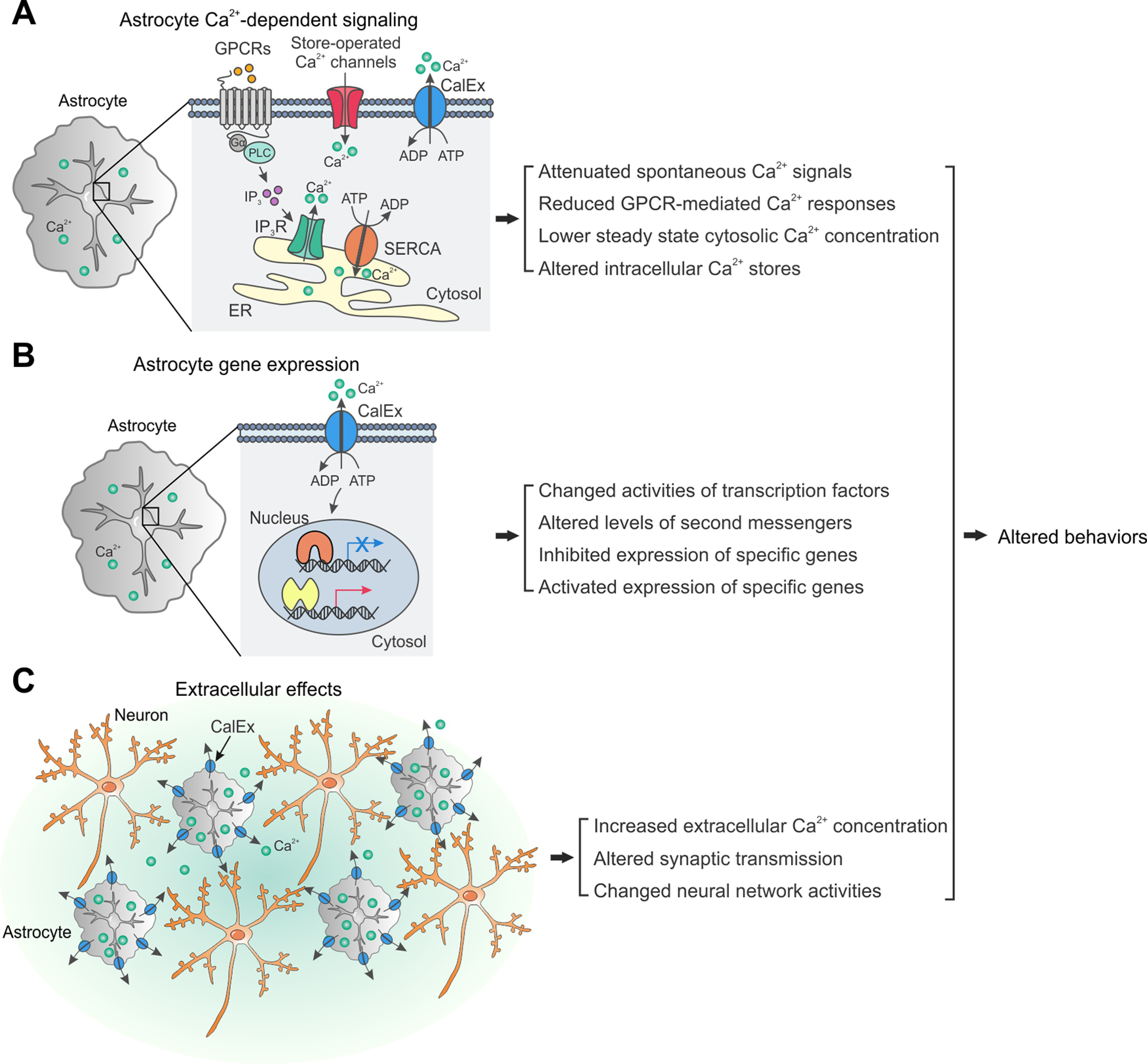

Figure 8.

Schematics to illustrate descriptive models of astrocyte CalEx-induced effects that are reported in this study. A, Astrocyte Ca2+-dependent signaling. Extrusion of Ca2+ by CalEx in astrocytes alters intracellular Ca2+ handling. The major Ca2+ sources in astrocytes include SOCs and various calcium-permeable pumps located on the plasma membrane, IP3 receptors, and SERCA pumps located on the ER. B, Astrocyte gene expression. CalEx expression in astrocytes triggers transcriptional changes that are independent of intracellular Ca2+ signaling through a currently unknown mechanism. C, Extracellular effects. CalEx expression in astrocytes exports sufficient amount of Ca2+ ions into the extracellular space to alter synaptic transmission and neural circuit activity. Some combination of all three models could operate in parallel.

Generation and validation of knock-in CalExflox mice

Generation of CalExflox mice

hPMCA2w/b is an exogenous constitutively active pump that extrudes cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 1A) and results in attenuated astrocyte Ca2+ signaling (Yu et al., 2018). CalExflox knock-in mice harbor a CMV-IE enhancer/chicken β-actin/rabbit β-globin hybrid promoter (CAG), followed by a loxP-3xSV40pA-loxP STOP cassette and the mCherry-hPMCA2w/b cDNA at the Rosa26 locus (Madisen et al., 2015; Fig. 1A,B; Materials and Methods). Following four rounds of blastocyst injections with suitably validated recombinant JM8N4 ES cell clones, two founder lines of CalExflox knock-in mice were generated (CalExflox mice; lines 1 and 2). The insertion of the mCherry-hPMCA2w/b transgene was confirmed by PCR of genomic DNA from tail biopsies (Materials and Methods). Both lines underwent germline transmission, with line 1 producing slightly higher expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b protein than line 2 from initial characterization with IHC. The founders from line 1 were thus backcrossed with C57BL/6NTac mice for more than eight generations for subsequent experimental validations. Both homozygous and heterozygous CalExflox mice were viable and fertile without any noticeable behavioral alterations. In this study, we characterized heterozygous CalExflox mice from line 1 in detail with either Cre AAV microinjections or with crosses to Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 expressing mice. Line 1 CalExflox mice have been deposited at JAX with descriptor Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(CAG-mCherry-hPMCA2w/b)Khakh (Stock No. 035252).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) validation of CalExflox mice

To validate CalExflox mice for attenuating astrocyte Ca2+ signaling, we generated brain region-specific expression using an AAV2/5 encoding Cre recombinase under the astrocyte promoter GfaABC1D. With this AAV strategy, experiments were performed 3–21 d after microinjections into ∼56 d old adult mice (Fig. 1B). Based on past work and our research interests, we chose the dorsal striatum and the hippocampal CA1 region to evaluate CalExflox mice (Srinivasan et al., 2016; Chai et al., 2017). We detected no mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in CalExflox mice in the absence of Cre (n = 5 and 6 mice for the striatum and the hippocampal CA1, respectively; Fig. 1C). In contrast, microinjection of AAV2/5-GfaABC1D-Cre induced robust mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in both the dorsolateral striatum and the hippocampal CA1 regions of adult CalExflox mice (n = 5 mice for both regions; Fig. 1D). The mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expressing cells resembled astrocytes in their morphology and the expression of the transgene co-localized with S100β, which labels astrocytes in these brain regions (Srinivasan et al., 2016; Chai et al., 2017). Notably, the bushy nature of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expressing cells (Fig. 1E,F) was similar to that of astrocytes expressing plasma membrane targeted fluorescent proteins (Benediktsson et al., 2005; Shigetomi et al., 2013; Srinivasan et al., 2016).

We next examined the time course of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression 3, 7, 14, and 21 d after microinjection of Cre AAVs into the striatum or hippocampus (Fig. 1G,H). We observed significant mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression 7 d after AAV microinjections in both brain regions (n = 5 mice per region, for the striatum: U = 0, p = 0.005 compared with background intensity; for the hippocampus: U = 1, p = 0.02 compared with background intensity; Mann–Whitney test). Subsequently, expression levels increased slightly and were maintained at 14 d (n = 4 mice per region, for the striatum: U = 0, p = 0.009 compared with background intensity; for the hippocampus: U = 0, p = 0.018 compared with background intensity; Mann–Whitney test) and 21 d (n = 6 mice per region, for the striatum: U = 0, p = 0.004 compared with background intensity; for the hippocampus: U = 0, p = 0.008 compared with background intensity; Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 1G,H). Expression in the striatum (but not the hippocampus) was significant 3 d after Cre AAV microinjections (n = 4 mice per region, for the striatum: U = 0, p = 0.009 compared with background intensity; for the hippocampus: U = 8.5, p = 0.80 compared with background intensity; Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 1G). Thus, CalExflox mice result in faster expression and improve on limitations with GfaABC1D-mCherry-hPMCA2w/b AAVs (Yu et al., 2018), which typically require two to three weeks of expression. The IHC experiments show that CalExflox mice can be used to express mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in a cell type-specific and brain region-specific manner.

Functional validation of CalExflox mice with GfaABC1D-Cre AAV2/5

For the functional validation experiments with CalExflox mice, we focused on the striatum because of the availability of past data for comparisons (Jiang et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2018, 2020b). We evaluated whether expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b from CalExflox mice affected striatal astrocyte Ca2+ signaling and animal behavior and compared the data to published work (Yu et al., 2018, 2020b). Delivery of two GfaABC1D promoter AAVs results in high co-expression of the cognate cargo from each AAV in the same population of striatal astrocytes (Srinivasan et al., 2016; Chai et al., 2017; Octeau et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018; Diaz-Castro et al., 2019; Nagai et al., 2019). Thus, we microinjected AAV2/5-GfaABC1D-GCaMP6f to express the fast Ca2+ indicator GCaMP6f (Chen et al., 2013) together with either a control AAV (AAV2/5-GfaABC1D-tdTomato) or a Cre AAV (AAV2/5-GfaABC1D-Cre) into the dorsal striatum of adult CalExflox mice and performed Ca2+ imaging of striatal astrocytes in striatal slices with two-photon laser-scanning microscopy (Fig. 2A). Extensive spontaneous Ca2+ signals were detected and analyzed from the somata, major branches, and areas encompassing entire territories of striatal astrocytes (Fig. 2B). mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression significantly reduced the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ signals in all compartments, which was clear from the representative traces (Fig. 2B) and from the individual and average data (Fig. 2C). The effect on the somata was most pronounced resulting in a decrease from 0.48 ± 0.10 events/min with control AAV to 0.04 ± 0.02 events/min with Cre AAV (n = 22–27 cells from 4–5 mice, U = 521, p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 2B,C). The frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ signals in the CalExflox mice following Cre AAV microinjections was also reduced in the major branches (1.20 ± 0.13 events/min with control AAV vs 0.23 ± 0.07 events/min with Cre AAV, U = 552.5, p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test) and territories of striatal astrocytes (1.05 ± 0.13 events/min with control AAV vs 0.36 ± 0.07 events/min with Cre AAV, U = 506.5, p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test). Moreover, the amplitudes and durations of spontaneous Ca2+ signals were all attenuated in striatal astrocytes in CalExflox mice following AAV Cre microinjections (Fig. 2B,C).

To capture the spatiotemporal dynamics of complex Ca2+ signals, we used recently developed software called astrocyte quantitative analysis (AQuA; Wang et al., 2019), and performed event-based analysis (Fig. 2D). Over 60 s of imaging, we detected significantly fewer events in striatal astrocytes from CalExflox mice with Cre AAV compared with those with control AAV (168 ± 35 events/cell vs 564 ± 59 events/cell, n = 29–31 cells from 4–5 mice, U = 211, p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 2E; Movies 1, 2). In striatal astrocytes expressing CalEx, the areas occupied by the largest Ca2+ events, which represent waves, were significantly reduced (p < 0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test; Fig. 2E). For instance, ∼10% of the total Ca2+ events measured in control astrocytes displayed areas larger than 20 µm2, but following Cre-mediated mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression this was ∼0.7%. Consistent with the analysis from different cellular compartments (Fig. 2A–C), the probability of Ca2+ events displaying shorter durations was significantly higher in CalEx-expressing astrocytes (p < 0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test). Additionally, the network spatial density within 10 s time windows from the imaged area (∼100 × 100 µm) was significantly lower in CalEx expressing astrocytes (p < 0.0001, Kruskal–Wallis test; Fig. 2E). Together, these data show profound global reduction of Ca2+ signaling following mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in CalExflox mice irrespectively of whether the data are analyzed using ROIs (Fig. 2A–C) or event-based analysis methods (Fig. 2D,E).

A 1-min recording of spontaneous Ca2+ signals in control striatal astrocytes from a CalExflox mouse with events colored by AQuA.

A 1-min recording of spontaneous Ca2+ signals in a Cre-expressing striatal astrocyte from a CalExflox mouse with events colored by AQuA.

Astrocytes respond to the activation of diverse GPCRs by elevating intracellular Ca2+ levels (Porter and McCarthy, 1997; Fiacco et al., 2009). We next examined whether CalExflox mice can be used to attenuate GPCR-mediated responses in astrocytes in striatal slices. AAV Cre mediated mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in CalExflox mice resulted in significantly attenuated 10 μm PE-evoked Ca2+ responses in astrocyte somata, major branches, and territories by ∼90% (Movies 3, 4; n = 13–17 cells from 4–5 mice, for the somata: U = 217, p < 0.0001; for the major branches: U = 217, p < 0.0001; for the territories: U = 206, p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 2F,G). Similarly, 100 μm ATP evoked astrocyte Ca2+ responses in striatal astrocytes were also reduced significantly by ∼90% (n = 11–16 cells from four mice, for the somata: U = 176, p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test; for the major branches: U = 176, p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test; for the territories: t(15.31) = 6.58, p < 0.0001, Student's t test with Welch correction; Fig. 2H,I). In these settings, PE and ATP activate α1 adrenoceptors and a mixture of metabotropic ATP P2Y receptors on striatal astrocytes, respectively (Chai et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2018; Nagai et al., 2019).

A 10-min recording of Ca2+ responses to 10 µM PE in a control striatal astrocyte from a CalExflox mouse.

A 10-min recording of Ca2+ responses to 10 µM PE in a Cre-expressing striatal astrocyte from a CalExflox mouse.

We previously demonstrated that attenuating spontaneous and GPCR-mediated Ca2+ signaling in striatal astrocytes of adult mice led to excessive self-grooming behaviors (Yu et al., 2018). To investigate whether mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression from CalExflox mice can reproduce those findings, we microinjected Cre AAV bilaterally into the dorsal striatum and evaluated innate self-grooming behavior of the mice (Fig. 2J–L). CalExflox mice that received Cre AAV showed significantly longer self-grooming bouts compared with CalExflox mice that received control AAV (16.3 ± 2.7 s per min with Cre AAV vs 5.9 ± 4.7 s per min with control AAV, n = 10 and 7 mice, respectively, t(15) = −3.63, p = 0.002, Student's t test; Fig. 2K,L). As expected, the number of self-grooming bouts was not altered (t(15) = −1.47, p = 0.16, Student's t test; Fig. 2L). Overall, the effects of striatal astrocyte mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in CalExflox mice reproduced cellular and behavioral effects that were expected to result from attenuated astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in this brain region.

Bigenic CalExflox/wt/Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice for CNS-wide attenuation of Ca2+ signals

In light of the emerging data on region-specific astrocytes (Haim and Rowitch, 2017; Khakh and Deneen, 2019; Pestana et al., 2020), functions within neural circuits are best explored by performing circuit-specific astrocyte manipulations. This could be achieved with local striatal microinjections (Figs. 1, 2) or with genetic approaches that target regionally specific subpopulations of astrocytes (Huang et al., 2020), which do not yet exist for the striatum. Such local approaches are preferable to whole brain manipulations, where the consequences may be problematic to interpret (Khakh and McCarthy, 2015; Khakh, 2019; Yu et al., 2020a). However, a previous approach to abrogate astrocyte Ca2+ signaling with IP3R2−/− mice in the whole CNS resulted in no changes in mouse behavior in the early explorations (Agulhon et al., 2008, 2010; Petravicz et al., 2008, 2014). This was interpreted to indicate that astrocyte Ca2+ signaling may not play a prominent physiological role within the brain. Subsequently, the discovery of additional types and residual Ca2+ signals in IP3R2−/− mice motivated reconsideration of the original conclusions (Otsu et al., 2015; Srinivasan et al., 2015; Rungta et al., 2016; Agarwal et al., 2017; Bindocci et al., 2017), and several studies have used the same mice and detected changes in mouse behavior during more specialized investigations (Savtchouk and Volterra, 2018; Yu et al., 2020a; Nagai et al., 2021). As additional validation of CalExflox mice, we therefore explored the consequences of CNS-wide astrocyte Ca2+ attenuation by crossing CalExflox mice with Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice to generate bigenic mice in which tamoxifen triggered global mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in adults (Srinivasan et al., 2016).

Behavioral abnormalities in bigenic CalExflox/wt/Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice

Since the expression of transgenes with Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice by tamoxifen was shown to be dose dependent (Srinivasan et al., 2016), we administrated tamoxifen using two regimens (multiple doses at 75 mg/kg body weight for five consecutive days, or a single dose for 1 d; Fig. 3A). Four groups of adult mice at six to eight weeks old were used in the experiments: (1) wild-type mice; (2) Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice; (3) CalExflox/wt mice; and (4) bigenic (CalExflox/wt; Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2) mice. In the multiple dose tamoxifen group, 3 d after the initial dose of tamoxifen was administered, the bigenic mice deteriorated rapidly, displaying reduced mobility, ruffled fur, and hunched postures. However, their littermate controls were normal (n = 7–19 mice; Fig. 3B). We tracked several cohorts of mice, each comprising mixed numbers and genders of control and bigenic mice after tamoxifen administration, and found that survival decreased sharply in bigenic mice 6 d after the initial dose of tamoxifen (n = 7–19 mice per group, χ2 = 41.74, p < 0.0001, Kaplan–Meier estimate; Fig. 3C). Of the bigenic mice examined, 92% were dead by day 7, whereas 97% of the controls were alive. Although the bigenic mice showed a trend of body weight loss close to the mortality end point, there were no statistical differences in body weight between groups (n = 4–6 mice per group, F(3,18) = 1.41, p = 0.27, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3D). In addition, we assessed behaviors related to exploration, motor coordination, and motor function. In an open-field test, the bigenic mice displayed lower ambulation, traveling significantly less distance compared with control mice (n = 6–10 mice per group, F(3,27) = 8.78, p = 0.0003, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 3E,F). The time spent in the center of the open-field arena was indiscernible among groups (F(3,27) = 1.81, p = 0.17, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3F). In a rotarod test, the latency for the bigenic mice to fall off the accelerating rod was significantly shorter than control mice, indicating altered motor coordination and balance (n = 5–9 mice per group, F(3,27) = 5.92, p = 0.003, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 3G). To assess the gait of mice, we performed a hindlimb footprint test and found that bigenic mice showed significantly shorter stride lengths (n = 6–9 mice per group, F(3,26) = 20.62, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test), but normal stride widths compared with control mice (F(3,26) = 0.12, p = 0.94, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3H,I).

In the single dose tamoxifen group, the bigenic mice exhibited similarly declining/worsening appearances and high mortality 6 d after receiving the single dose of tamoxifen. Compared with the multiple dose group, the bigenic mice with low dose tamoxifen had extended survival, e.g., 29% of bigenic mice were alive on day 7 compared with 8% in multiple dose group (Fig. 3J). None of the control mice died during the course of experiments and body weight was similar among different groups (n = 4–7 mice per group, F(3,19) = 1.12, p = 0.37, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3K). Similarly, bigenic mice traveled less distance in the open-field test because of decreased mobility (n = 7–10 mice per group, F(3,29) = 8.28, p = 0.0004, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 3L). Although the time spent in the center of the arena was significantly less in bigenic mice when comparing with wild-type littermates (F(3,29) = 3.77, p = 0.032 vs wild-type, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test), it was not different from the other control groups (p = 0.18 vs Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2, p = 0.12 vs CalExflox/wt; Fig. 3L). Moreover, bigenic mice showed deteriorated performance in the rotarod test (n = 8–10 mice per group, F(3,30) = 4.43, p = 0.011, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 3M) and altered hindlimb gait (n = 5–8 mice per group, for stride length: F(3,22) = 10.50, p = 0.0002, for stride width: F(3,22) = 0.94, p = 0.44, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 3N). Together, our data suggest that astrocytic expression of CalEx in the CNS markedly affected physiology (see Discussion).

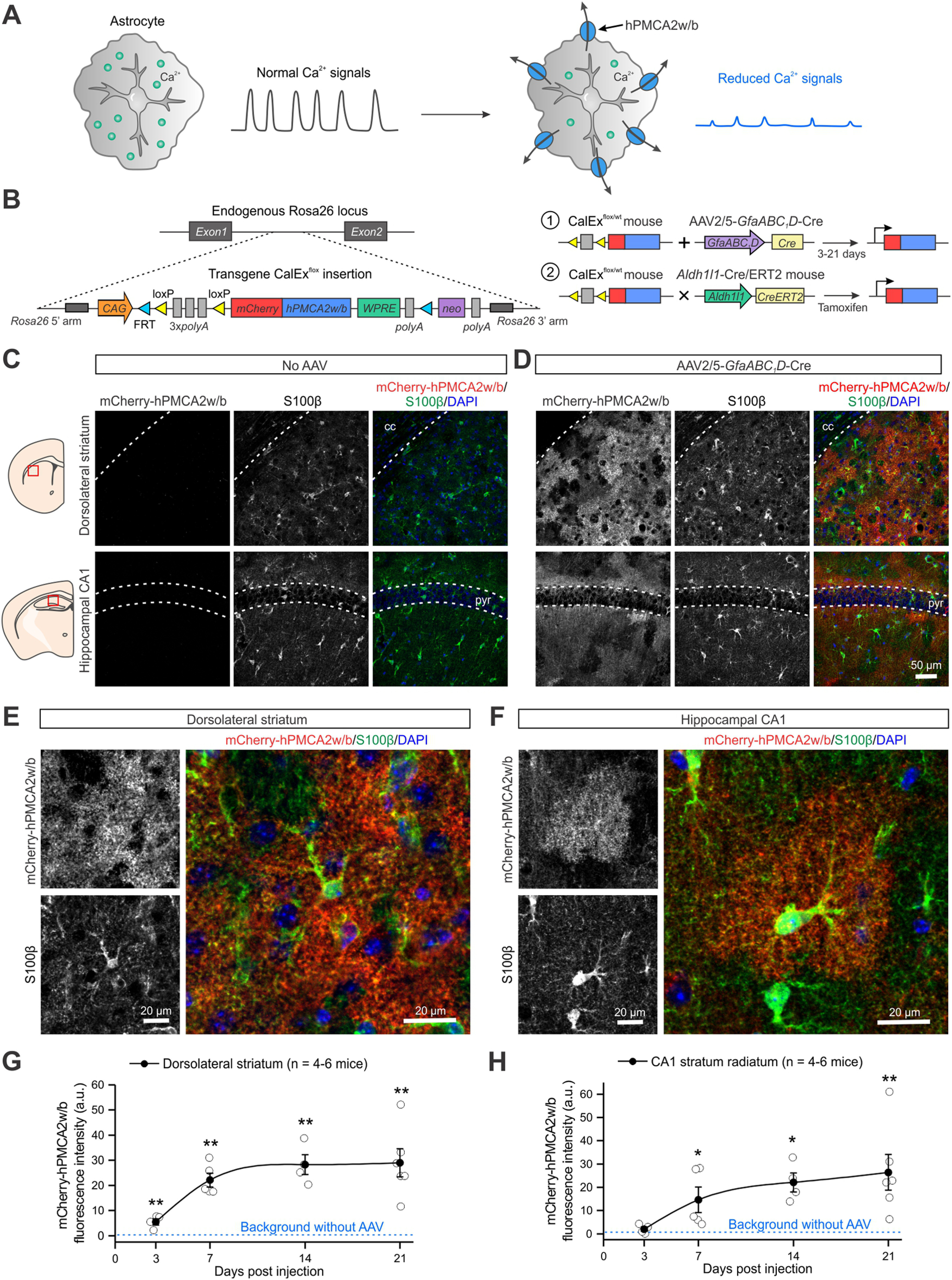

Preferentially strong cerebellar expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in bigenic mice

To investigate the brain regions that may underlie behavioral alterations in bigenic mice, we surveyed the expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b across the CNS of bigenic mice treated either with multiple doses of tamoxifen or with a single dose. We found that mCherry-hPMCA2w/b was expressed throughout the brain and spinal cord of bigenic mice, but undetectable in all three control groups (Fig. 4A). Notably, the expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b within the cerebellum was particularly high and localized to the molecular layer where the Bergmann glia processes enwrap the synapses of the Purkinje neurons (n = 3–5 mice; Fig. 4A). We further quantified mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression from 14 CNS regions including the olfactory bulb (Ob), the motor cortex (MCx), the sensory cortex (SCx), the visual cortex (VCx), dorsal striatum (dSt), nucleus accumbens (NAc), hippocampal CA1, thalamus (Th), hypothalamus (Hy), substantia nigra (SNr), facial motor nucleus (7N) in the hindbrain, cerebellum (Cb), cervical spinal cord (CSc), and lumbar spinal cord (LSc; Fig. 4B,C). Across 14 CNS regions, the percentage of S100β+ cells expressing mCherry-hPMCA2w/b ranged from ∼33% (MCx) to 94% (Cb, n = 3–5 mice per region, F(13,52) = 20.01, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 4D; Table 1) with multiple tamoxifen doses. No NeuN+ cells expressed mCherry-hPMCA2w/b (Fig. 4B,D). The proportion of astrocytes expressing mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in the bigenic mice was lower overall with a single dose of tamoxifen, however the cerebellum still showed significantly higher expression (9% in MCx vs 57% in Cb, n = 4–8 mice per region, F(13,85) = 13.18, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test; Fig. 4E; Table 1). Furthermore, the intensity of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b fluorescence in individual cells from all 14 CNS regions was also the strongest in Bergmann glia of the Cb in bigenic mice with multiple tamoxifen doses (n = 69–148 cells per region from 3–5 mice, F(13,1439) = 65.04, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test; Table 1) and with a single dose (n = 27–129 cells per region from 4–8 mice, F(13,753) = 100.49, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test; Table 1). There was no detectable change in tissue architecture in any brain region (Fig. 5A) and there was no expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in peripheral organs except low levels in the small intestine (Fig. 5B,C). Thus, the data suggest that the high and strong mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in Bergmann glia of the Cb is the most parsimonious explanation for the motor abnormalities that were observed (Fig. 3).

Figure 4.

Expression of mCherry-hPMCAw2/b was the greatest in the cerebellum of bigenic mice. A, IHC images of the sagittal sections of the entire brain and coronal sections of the spinal cord showing a global expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in bigenic mice that received tamoxifen but not in control mice (CalExflox or Aldh1l1-Cre/ERT2 mice). B, IHC images of seven brain regions showing expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in bigenic mice with multiple doses of tamoxifen injection (bottom). mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression colocalized with astrocyte marker S100β (middle) but not neuronal marker NeuN (top). C, IHC images of seven brain regions showing expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in bigenic mice with single dose tamoxifen injection. D, Quantification of the percentage of S100β+ cells and NeuN+ cells that colocalized with mCherry-hPMCA2w/b across 14 CNS regions in bigenic mice with multiple doses of tamoxifen injection. Compared with other areas, the cerebellum has the highest percentage of S100β+ cells expressing mCherry-hPMCA2w/b (n = 3–5 mice per region, F(13,52) = 20.01, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test). No neuronal expression was detected. E, The percentage of S100β+ cells colocalized with mCherry-hPMCA2w/b is the greatest in the cerebellum across 14 CNS regions in bigenic mice with single dose tamoxifen injection (n = 4–8 mice per region, F(13,85) = 13.18, p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test). Ob, olfactory bulb; MCx, motor cortex; SCx, sensory cortex; VCx, visual cortex; dSt, dorsal striatum; NAc, nucleus accumbens; CA1, hippocampal CA1; Th, thalamus; Hy, hypothalamus; SNr, substantia nigra; 7N, facial motor nucleus; Cb, cerebellum; CSc, cervical spinal cord; LSc, lumbar spinal cord. The average data are shown as mean ± SEM. In some cases, the SEM symbol is smaller than the symbol for the mean; ***p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in 14 CNS regions of bigenic mice

| CNS regions (rostral to caudal) | Multiple (5) tamoxifen 75 mg/kg, i.p. injections |

Single tamoxifen 75 mg/kg, i.p. injection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b+ and S100β+ (%) | mCherry-hPMCA2w/b intensity per cell (a.u.) | Percentage of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b+ and S100β+ (%) | mCherry-hPMCA2w/b intensity per cell (a.u.) | |

| Ob | 47.5 ± 5.0 | 71.2 ± 2.8 | 24.0 ± 6.0 | 37.9 ± 2.1 |

| MCx | 33.0 ± 4.1 | 77.1 ± 4.0 | 9.3 ± 2.4 | 29.9 ± 3.1 |

| SCx | 33.5 ± 3.2 | 81.6 ± 3.4 | 6.6 ± 1.9 | 29.6 ± 3.0 |

| VCx | 35.3 ± 2.7 | 76.1 ± 3.5 | 8.6 ± 2.0 | 34.6 ± 2.3 |

| dSt | 45.8 ± 5.0 | 51.8 ± 1.3 | 9.8 ± 1.2 | 20.5 ± 1.9 |

| NAc | 36.8 ± 1.7 | 61.8 ± 3.8 | 9.3 ± 2.2 | 25.4 ± 2.9 |

| CA1 | 33.3 ± 3.0 | 62.2 ± 2.5 | 6.3 ± 1.6 | 25.1 ± 1.8 |

| Th | 43.3 ± 2.5 | 60.4 ± 1.8 | 17.6 ± 4.3 | 21.5 ± 1.0 |

| Hy | 50.1 ± 2.1 | 68.5 ± 2.3 | 19.6 ± 3.8 | 24.8 ± 1.1 |

| SNr | 46.3 ± 5.2 | 62.0 ± 2.4 | 12.4 ± 2.1 | 26.5 ± 1.1 |

| 7N | 61.1 ± 4.3 | 65.0 ± 2.1 | 17.8 ± 3.5 | 31.3 ± 1.4 |

| Cb | 94.3 ± 1.1 | 134.5 ± 3.7 | 57.4 ± 8.1 | 75.1 ± 1.8 |

| CSc | 42.6 ± 2.9 | 59.3 ± 2.2 | 22.5 ± 4.4 | 25.3 ± 1.1 |

| LSc | 50.8 ± 5.5 | 67.6 ± 1.9 | 22.5 ± 3.5 | 28.8 ± 1.6 |

The data are reported from between three and eight mice in each case.

Ca2± signaling attenuation in Bergmann glia by mCherry-hPMCA2w/b

To evaluate whether mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression affects Ca2+ signaling in Bergmann glia, we microinjected AAV2/5-GfaABC1D-GCaMP6f together with either the control or Cre AAVs into the cerebellum of CalExflox mice and performed Ca2+ imaging on brain slices two to three weeks later (Fig. 6A). This approach permitted co-expression of GCaMP6f and mCherry-hPMCA2w/b in Bergmann glia (Fig. 6B,C). The expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b was substantial in Bergmann glia processes that extended through the molecular layer (Fig. 6C). It has been reported that Bergmann glia express various GPCRs that couple to Ca2+ release from intracellular stores, including α1-adrenoceptors and P2 purinergic receptors (Kulik et al., 1999; Piet and Jahr, 2007). Consistently, bath application of GPCR agonists (10 μm PE or 100 μm ATP) triggered robust Ca2+ increases in Bergmann glia of CalExflox mice that received the control AAV (Fig. 6D–I). Expression of mCherry-hPMCA2w/b significantly attenuated 10 μm PE-evoked Ca2+ responses by ∼90% in the somata of Bergmann glia (n = 39–67 cells from 4–6 mice per group, U = 2602, p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 6E,F). A similar effect was observed with ATP application and the Ca2+ responses of Bergmann glia were reduced by ∼80% in CalExflox mice with the Cre AAV (n = 26–55 cells from 5 mice per group, U = 1413, p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 6H,I).

Cerebellar transcriptomic changes in multiple cell types by Bergmann glia Ca2± attenuation

To explore the molecular alterations induced by Bergmann glia Ca2+ attenuation on whole cerebellar tissue in an unbiased manner, we employed RNA-seq to profile the transcriptomic changes in bigenic mice (Fig. 7A). Five days after a single dose of tamoxifen, RNA was extracted from the cerebella of CalExflox/wt mice (control) and bigenic mice for sequencing and subsequent analyses (n = 4 mice per group; Fig. 7A). Comparing the bulk RNA-seq data between bigenic and control mice, we identified 7923 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the Cb, with 4146 DEGs downregulated and 3777 DEGs upregulated (FPKM > 0, fold change > 1, FDR < 0.05; Fig. 7B; Extended Data Table 7-1). Taking the transcript abundance into consideration, we further applied different thresholds including the level of expression (FPKM) and the degree of change (fold change; Fig. 7B). By assigning FPKM of 5 and fold change of 2, there were 314 DEGs detected, with 147 downregulated DEGs and 167 upregulated DEGs. We next evaluated the top 50 DEGs ranked by the degree of expression change induced by Bergmann glia Ca2+ attenuation, which ranged from 468-fold decrease (Ttr) to 16-fold increase (Lcn2; FPKM > 5, FDR < 0.05; Fig. 7C). The biological functions that are associated with these profound cerebellar changes included ion transport, apoptotic process, transcription regulation, endocytosis and cell proliferation/growth/migration (Fig. 7C). Among the top 50 DEGs, the most upregulated gene was Lcn2, which is considered as a pro-inflammatory factor and a marker gene for reactive astrocytes. To examine whether Bergmann glia Ca2+ attenuation triggered astrogliosis, we assessed the expression of a panel of 38 genes containing pan reactive, A1-specific and A2-specific markers that identify reactive astrocytes (Liddelow et al., 2017). Compared with positive control of neuroinflammation using lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the changes in these 38 reactive astrocyte markers induced by Bergmann glia Ca2+ attenuation was moderate (Fig. 7D). Specifically, the average increase across all markers was 3.3 ± 1.4-fold in the Cb of bigenic mice versus 19.2 ± 5.7-fold in LPS. Based on identified gene expression changes (FPKM > 1, FDR < 0.05), we summarized the top 10 canonical pathways that were significantly altered in the cerebellar tissue (p < 0.05; Fig. 7E). Nine out of ten pathways were found to be activated by Bergmann glia Ca2+ attenuation, including senescence pathway, synaptogenesis signaling pathway and stress response. In contrast, a signaling pathway mediated by PTEN tumor suppressor (Lee et al., 2018) was significantly inhibited. Thus, Bergmann glia Ca2+ attenuation in bigenic mice resulted in pronounced changes in the whole cerebellar tissue for both genes and signaling pathways.

Similar to other brain regions, the Cb is composed of different cell types. We next investigated how Bergmann glia Ca2+ attenuation affects various cell populations by integrating the bulk RNA-seq data with previously published single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) data of the adult mouse Cb (Zeisel et al., 2018). The Cb scRNA-seq generated transcriptomic profiles of 11,063 cells and identified 11 transcriptomic clusters corresponding to known major cerebellar cell types. We used the top 1000 genes for six most dominant cerebellar cell types as a reference and mapped DEGs identified from bulk RNA-seq (FPKM > 1, FDR < 0.05) to explore the cell-type-specific alterations by Bergmann glia Ca2+ attenuation (Fig. 7F). The highest proportion of DEGs was mapped to neurons (∼37.8%), followed by astrocytes (∼17.4%), microglia (∼16.7%), oligodendrocytes (∼10.7%), ependyma (∼8.8%), and fibroblast-like cells (∼8.6%). Specifically, Purkinje cells were the most affected neuronal populations, with ∼17% DEGs mapped. This result is in accordance with the close proximity between Bergmann glia and Purkinje cells as well as their communications via Bergmann glia Ca2+ signals. Together, these data suggest global modification of the molecular identities of diverse cells in the Cb by Bergmann glia Ca2+ attenuation. We suggest such changes are the likely cause of the behavioral alterations we observed and together the data show strong consequences of CalEx expression in astrocytes. We emphasize that our data do not explain why the mice die prematurely; this is problematic to address with brain wide expression of CalEx. Instead, the experiments provide plausible hypotheses for the motor deficits that were observed and suggest cerebellar defects as a likely cause.

Mechanistic interpretations and considerations

The use of CalExflox mice resulted in clearly attenuated astrocyte intracellular Ca2+ signaling (Figs. 2, 6), triggered behavioral alterations (Figs. 2, 3), and induced transcriptomic changes (Fig. 7). How should one interpret and potentially connect these findings across scales? We interpret these findings in the context of three descriptive models, which are independent, but non-exclusive (Fig. 8). In the first model, CalEx acts as it was intended – as a Ca2+ extruder on the plasma membrane of astrocytes to reduce intracellular Ca2+ signaling (Yu et al., 2018). This would reduce Ca2+-dependent processes within astrocytes and also alter Ca2+ handling within the cells, which is orchestrated by operations of several Ca2+ sources including store-operated Ca2+ channels (SOCs) and Ca2+ pumps (PMCAs) located on the plasma membrane, as well as IP3 receptors and SERCA pumps located on the ER (Fig. 8A). Such interpretations are consistent with published data using CalEx, whereby Ca2+ handling resulting from intracellular Ca2+ store depletion was significantly altered (Yu et al., 2018). Furthermore, attenuated Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes by CalEx may induce transcriptional and translational modifications that lead secondarily to synaptic and circuit level changes and ultimately altered behaviors (Yu et al., 2018). This model thus includes two components: primary effects because of altered dynamics of Ca2+ signaling and secondary effects dues to changes in Ca2+-dependent gene expression. Such interpretations align with the fact that Ca2+ ions serve as second messengers for numerous essential physiological functions within cells over a wide range of spatiotemporal scales (Clapham, 2007) and are consistent with the breadth of data on astrocyte Ca2+ signaling (Volterra et al., 2014; Bazargani and Attwell, 2016; Shigetomi et al., 2016). The second model proposes an effect of CalEx on gene expression in astrocytes that is independent of intracellular Ca2+ signaling (Fig. 8B). Although there is no evidence supporting PMCA's direct modulation of gene expression, one possible scenario how this could occur is that CalEx alters the expression of endogenous PMCA and its associated modulators such as cAMP and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (Kuo et al., 1993; Abramowitz et al., 2000), which may conceivably drive changes in signal transduction and gene regulation that contribute to some of the metrics reported in this study. In the third model, CalEx exports sufficient astrocytic intracellular Ca2+ into the extracellular space such that this additional Ca2+ directly alters synaptic transmission and electrical properties of neurons, which then contribute to subsequent behavioral outcomes (Fig. 8C). We cannot rule out this scenario, but consider the likelihood to be relatively low. The pool of extracellular Ca2+ concentration is substantially larger (∼104 times) than that of intracellular Ca2+ levels within astrocytes (Shigetomi et al., 2016) and so the additional change by CalEx, if it occurred, would be moderate and dissipated quickly by diffusion. In addition, neither fast inhibitory or excitatory synaptic transmission onto medium spiny neurons was affected by CalEx expression in striatal astrocytes (Yu et al., 2018). This is of note, because neurotransmitter release probability has a very steep dependency on Ca2+ concentration and would be expected to change if extracellular Ca2+ changed meaningfully. It also seems reasonable to suggest that the behavioral results reported by us may reflect a combination of all three models, which are as of yet hard to tease apart. Of the three models, the first one is informative from the perspective of astrocyte biology, but the latter two may produce coincidental effects that are significant, but nonetheless not reflective of astrocyte biology in a physiological sense. We have recently discussed the necessity to assess astrocyte findings by proposing three types of interpretations (Nagai et al., 2021). Within that framework, the first model represents a type 1 or type 2 interpretation, whereas the second and third models represents an indirect type 3 interpretation (Nagai et al., 2021). Our findings, and those in the future with the use of CalEx, should be interpreted cautiously from the perspective of multiple models to account for the empirical data across scales. Additional tools and approaches are needed to dissect astrocyte signaling more precisely.

Discussion

There are three main findings from this study. First, we provide a genetic tool to attenuate Ca2+ signals using knock-in CalExflox mice at the Rosa26 locus. In these mice, mCherry-hPMCA2w/b can be expressed in a Cre-dependent manner in genetically specified cells for which a Cre mouse line or Cre-expressing virus exists. mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression was controlled by Cre expression and caused ∼90% attenuation of Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes. CalExflox mice can be used to explore contributions of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in a brain-region-specific manner with local Cre AAV microinjections or with region-specific astrocyte Cre lines as they are developed. Our data provide validation of CalExflox mice, but do not obviate the need for further controls when the mice are used in future studies. This is important to consider since astrocytes are a heterogeneous population of cells and thus specific controls will be needed on a case-by-case basis for particular brain regions and Cre lines (Haim and Rowitch, 2017; Khakh and Deneen, 2019; Pestana et al., 2020). The necessity of experiments tailored to specific brain regions is exemplified by recent insights on the brain region-specific regulation of astrocyte function by transcription factors (Huang et al., 2020). Second, we explored the consequences of CalEx expression in astrocytes in a CNS-wide manner and observed profound alterations in mouse behavior and premature lethality. Third, we focused on the cerebellum based on the histologic analysis and identified molecular changes at the gene and pathway levels of multiple cell types that were associated with CalEx in Bergmann glia.

Several biological responses have been ascribed to astrocytes and are proposed to occur via intracellular Ca2+ signaling. These include regulation of neurons, contributions to diverse diseases, and control of blood flow (Araque et al., 2014; Howarth, 2014; Volterra et al., 2014; Khakh and McCarthy, 2015; Bazargani and Attwell, 2016; Verkhratsky and Nedergaard, 2018). CalExflox mice could be used to study such responses in vivo for genetically defined cell populations, e.g., Ca2+-dependent astrocyte contributions to motor function, olfactory responses, learning, circadian rhythms, and drug-evoked behaviors, as well as others (Nimmerjahn et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010; Brancaccio et al., 2017; Adamsky et al., 2018; Corkrum et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020; Ung et al., 2020). Furthermore, although we focused on astrocyte studies, CalExflox mice could be used to explore the consequences of attenuating Ca2+ signaling in other CNS cells including neurons, microglia, pericytes, oligodendrocytes, and endothelial cells for which reliable Cre lines exist. Our studies with bigenic mice show that strongly attenuating astrocyte Ca2+ signaling across the CNS with mCherry-hPMCA2w/b may lead to premature lethality, supporting the proposition that astrocyte Ca2+ may serve multiple critical functions rather than being inconsequential as was thought (Petravicz et al., 2008, 2014; Agulhon et al., 2010). Perhaps the simplest interpretation of premature lethality in the bigenic mice with CNS-wide astrocyte Ca2+ signaling attenuation is that several important responses were impaired (Fig. 8) beyond a critical threshold resulting in loss of essential functions and death, although admittedly we have not been able to determine why the mice died. In these regards, whole body IP3R2−/− mice do not display similar lethality (Petravicz et al., 2008, 2014; Agulhon et al., 2010), but it should be remembered that these mice display residual Ca2+ signaling that persisted after IP3R2 deletion (Di Castro et al., 2011; Srinivasan et al., 2015; Rungta et al., 2016; Agarwal et al., 2017). In addition, the deletion of IP3R2 throughout development may stimulate compensatory mechanisms that are unlikely to occur in the mature CNS after inducible mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression. In contrast to IP3R2 deficiency, mCherry-hPMCA2w/b has a broader impact on Ca2+ sources and Ca2+-dependent pathways including IP3-independent ones, which should be taken into account when interpreting the physiological significance of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling and our data (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, high mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in the cerebellum likely explains major motor dysfunctions that were observed in the bigenic mice. Our data are therefore broadly consistent with critical functions ascribed to astrocyte Ca2+ signaling such as regulation of multiple cell types, including neurons and neurovascular coupling (Attwell et al., 2010; Araque et al., 2014; Volterra et al., 2014; Khakh and McCarthy, 2015; Bazargani and Attwell, 2016; Shigetomi et al., 2016; Savtchouk and Volterra, 2018), and specific contributions to cerebellar function (Watanabe, 2002; Nimmerjahn et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010; Nimmerjahn and Bergles, 2015). We also consider alternative explanations that mCherry-hPMCA2w/b expression in astrocytes may trigger transcriptional and translational changes bypassing its Ca2+ regulatory function and that constitutive Ca2+ extrusion by mCherry-hPMCA2w/b may alter extracellular Ca2+ concentration and synaptic transmission (Fig. 8). All three proposed models are independent, but non-exclusive. For instance, it is conceivable that altered intracellular Ca2+-dependent signaling by CalEx may further induce transcriptional and posttranscriptional modifications of specific genes that have essential physiological functions. These mechanisms could be explored using CalExflox mice in a brain region-specific manner with specific hypothesis-driven experiments. In these regards, the CalExflox mice are a valuable addition to the toolbox available to explore astrocyte biology (Yu et al., 2020a).

We propose several interpretations of how CalEx influences astrocyte function, neuronal and circuit activity based on our experimental observations. The first model considers a causative relationship between astrocyte Ca2+-dependent signaling and behavior with an assumption that the level of Ca2+ signaling attenuation observed in CalExflox mice is accounted for by Ca2+ extrusion through hPMCA2w/b pumps. This idea can be theoretically tested by a data-driven mechanistic computational model of astrocyte Ca2+ dynamics in conjunction with CalExflox mice, for instance, with a single-compartment model (Handy et al., 2017; Taheri et al., 2017) or even better with ones that include a spatial dimension (Savtchenko et al., 2018). With further experimental data on astrocyte Ca2+ dynamics and fine structure at sufficient resolution to inform the modeling, underlying Ca2+ fluxes from different astrocyte subcellular regions such as major branches and processes could also be incorporated into the model to capture the complexity of astrocyte morphology and Ca2+ signaling. Moreover, such models could also incorporate astrocyte Ca2+ waves as has been done for cell culture experiments (Roth et al., 1995). Finally, to model astrocyte spatiotemporal Ca2+ dynamics, the single-compartment model could be extended. In order to construct an improved model, realistic constraints need to be obtained empirically using detailed 3D views of astrocyte morphology with high isotropic resolution electron microscopy and time resolved 3D imaging data with methods such as focused ion beam scanning electron microcopy (Xu et al., 2017) and with swept, confocally aligned planar excitation (SCAPE) microscopy (Voleti et al., 2019), respectively. Such data do not currently exist, but are much needed to develop models of astrocyte Ca2+ signals in cells with realistic geometry and dynamics.