Abstract

Background

An understanding of differences in clinical phenotypes and outcomes COVID-19 compared with other respiratory viral infections is important to optimise the management of patients and plan healthcare. Herein we sought to investigate such differences in patients positive for SARS-CoV-2 compared with influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other respiratory viruses.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of hospitalised adults and children (≤15 years) who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, influenza virus A/B, RSV, rhinovirus, enterovirus, parainfluenza viruses, metapneumovirus, seasonal coronaviruses, adenovirus or bocavirus in a respiratory sample at admission between 2011 and 2020.

Results

A total of 6321 adult (1721 SARS-CoV-2) and 6379 paediatric (101 SARS-CoV-2) healthcare episodes were included in the study. In adults, SARS-CoV-2 positivity was independently associated with younger age, male sex, overweight/obesity, diabetes and hypertension, tachypnoea as well as better haemodynamic measurements, white cell count, platelet count and creatinine values. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 was associated with higher 30-day mortality as compared with influenza (adjusted HR (aHR) 4.43, 95% CI 3.51 to 5.59), RSV (aHR 3.81, 95% CI 2.72 to 5.34) and other respiratory viruses (aHR 3.46, 95% CI 2.61 to 4.60), as well as higher 90-day mortality, ICU admission, ICU mortality and pulmonary embolism in adults. In children, patients with SARS-CoV-2 were older and had lower prevalence of chronic cardiac and respiratory diseases compared with other viruses.

Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2 is associated with more severe outcomes compared with other respiratory viruses, and although associated with specific patient and clinical characteristics at admission, a substantial overlap precludes discrimination based on these characteristics.

Keywords: COVID-19, respiratory infection, viral infection, pneumonia

Key messages.

What is the key question?

What are the differences in clinical phenotypes and outcomes in patients with SARS-CoV-2 as compared with influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other respiratory viruses such as seasonal coronaviruses, rhinovirus and metapneumovirus?

What is the bottom line?

Adult SARS-CoV-2 was associated with more severe outcomes compared with influenza, RSV and other respiratory viruses, and although associated with specific patient and clinical characteristics at admission, a substantial overlap precluded discrimination based on these characteristics.

Why read on?

To our knowledge, this is the first extensive comparison of baseline characteristics, clinical presentation and patient outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 as compared with influenza and several other respiratory viruses.

Introduction

The clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infected adults in hospitals includes fever, cough or dyspnoea, which are similar to those of other respiratory viruses.1–3 Common characteristics of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 are male sex, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension or obesity.4–6 A substantial portion of patients with COVID-19 require intensive care unit (ICU) admission and develop severe complications such as pulmonary embolism or acute kidney failure.4 5 7 8 There is some evidence for lower susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children, as well as more favourable disease outcome.9–12 These observations are primarily based on case series and how these characteristics and outcomes compares in similar cohorts of patients infected with other respiratory infections is less well studied.

SARS-CoV-2 will likely remain endemic and cocirculate in the population together with influenza and other respiratory viruses.13 14 To better understand the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 and to optimise patient management and plan healthcare, it is important to understand variations in clinical phenotypes and outcomes associated with different respiratory viruses. In this study, the aim was to investigate differences in baseline characteristics, clinical presentation and outcomes for adult and paediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with other respiratory viruses.

Methods

Patient population and study setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of hospitalised patients from October 2011 to September 2020 at Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, an academic centre with 1100 beds divided between two sites and serving a population of 2.3 million inhabitants. Patients with the following PCR-confirmed infections from respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal, throat, sputum, tracheal or bronchoalveolar lavage samples) on admission were included: influenza A (H3N2 and H1N1), influenza B (FluB), adenovirus, bocavirus, seasonal coronaviruses species 229E, NL63, OC43 and HKU1, enterovirus, metapneumovirus, rhinovirus (RV), parainfluenza viruses type 1–4 (PIV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and SARS-CoV-2 (see online supplemental eMethods 1 for additioal descriptions of PCR-methods). Samples collected within −24 hours to +48 hours from the hospital admission were included. Repeated positive tests within 90 days were excluded.

thoraxjnl-2021-216949supp001.pdf (3.9MB, pdf)

Data source and definitions

Data were obtained from a database of electronic health records of all patients admitted between January 2010 and September 2020, including demographics, International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes, body mass index (BMI), laboratory findings, vital signs, microbiology, intensive care and mortality. The study period start time of October 2011 was chosen to ensure at least 1.5 years of data on previous comorbidities and other variables. Specific individual comorbidities as well as Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and Elixhauser Comorbidity Index (ECI) scores were based on ICD-10 codes recorded from 5 years before and up until admission.15 BMI was based on the most updated height and weight available. For laboratory parameters and vital signs, the worst value −24 hours to +24 hours from admission was used. See online supplemental eMethods 1 for additional descriptions.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 30-day mortality from hospital admission. Secondary outcomes were length of stay (LOS) at hospital, 90-day mortality, ICU admission (defined as units that provide inotropic and non-invasive or invasive respiratory treatment), LOS at ICU, mortality after ICU admission (calculated from ICU admission), acute kidney injury (AKI; based on the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria16 but without urine volume measurements), pulmonary embolism (based on ICD-10 discharge code), acute myocardial injury (AMI; cardiac troponin T>50 ng/mL) and hospital-onset bacteraemia (HOB; significant findings in blood cultures taken >48 hours after admission).17 See online supplemental eMethods 2 for detailed definitions. Patients were followed for 30 days for outcome measures, except for pulmonary embolism where patients were followed until discharge and 90-day mortality.

Statistical analysis

Children (≤15 years of age) and adults were analysed separately. Analyses were performed using 10 virus categories as well as four virus groups in adults—SARS-CoV-2, influenza, RSV and other viruses—to correspond to differential virus testing indications. Testing for other viruses is preferentially performed in patients with more severe disease, with immunosuppression and tested negative for other viruses. All analyses were restricted to patients positive for only one virus group, in order to distinguish clinical phenotypes and outcomes for each virus group. For rhinoviruses and enteroviruses, PCR cross-reactivity, preventing classification of 572 health care episodes (HCE) (82 adult and 490 paediatric) into virus-specific groups.18 These 572 HCEs were excluded from virus-specific analyses, but adults were included in the other viruses group.

Multiple imputation with predictive mean matching was used to account for missing values for BMI, laboratory parameters and vital signs (proportion missing values 5%–13%) with other baseline characteristics and outcomes used as predictors (detailed description in online supplemental file).

Comparisons between all 10 virus groups were performed using χ2 test for nominal and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Sex- and age category adjusted logistic regression analyses were performed to compare baseline characteristics, laboratory parameters and vital signs in patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with influenza, RSV and other respiratory viruses. To investigate overall differences in baseline characteristics and clinical presentation between SARS-CoV-2 and influenza, RSV and other respiratory viruses, three logistic regression models were used. Predictors in the first model were age category, sex and BMI category, the second also included specific comorbidities and the third included laboratory parameters and vital signs as well. Model performance was assessed using area under the receiver operating characteristics (AUROC).

Clinical outcomes were compared among different virus groups using regression analyses with adjustment for sex, age category, BMI category and individual comorbidities: Cox regression HRs for 30-day and 90-day mortality, ICU admission, AMI, AKI and HOB, logistic regression ORs for pulmonary embolism and negative binomial regression rate ratios for LOS. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by Schoenfeld residuals. Kaplan-Meier curves and standardised adjusted survival functions were calculated for 30-day and 90-day mortality.15 In order to address potential time-related drifts in clinical management as well as more extensive testing of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with other viruses, predefined sensitivity analyses were performed for the outcomes mortality and ICU admission: (1) restriction to years 2015–2020, (2) restriction to patients with admission temperature ≥38°C, or oxygen saturation <95%, or respiratory rate >20, (3) stratification according to calendar time of SARS-CoV-2 positivity (February–April 2020 vs May–September 2020) and (4) restriction to the index HCE for each patient.

Statistical analyses were performed in R V.4.0.3.

Results

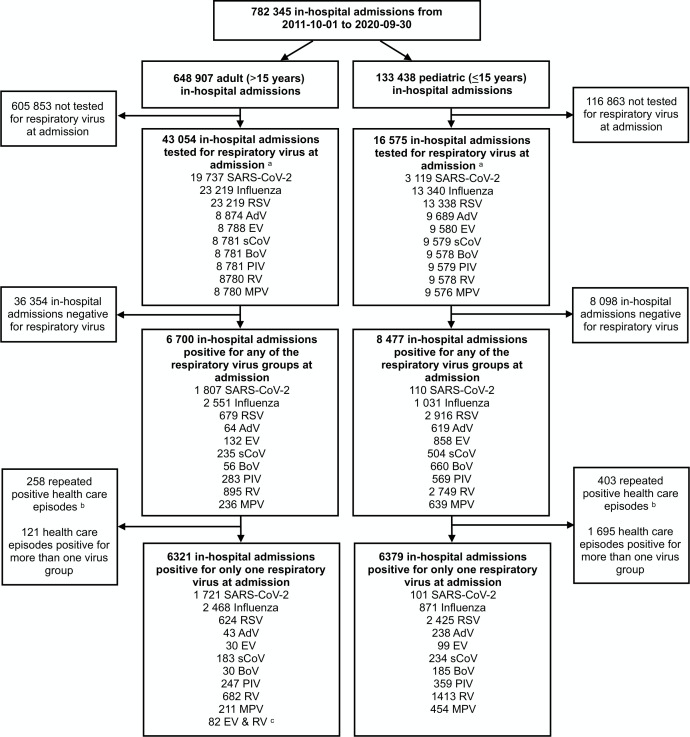

In total, 782 345 inpatient admissions in 412 115 patients were registered between October 2011 and September 2020, of which 6700 adult and 8477 paediatric episodes tested positive for a respiratory virus at admission (figure 1). There were 661 episodes with repeated positive tests within 90 days. In the analysis, 12 700 episodes with one respiratory virus detected were included, 6321 adults (1721 SARS-CoV-2, 2468 influenza, 624 RSV and 1508 other viruses) and 6379 children (101 SARS-CoV-2, 871 influenza, 2425 RSV and 2982 other viruses).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of adult and paediatric healthcare episodes in the study. aAdmission defined as −24 to +48 hours in relation to the admission time point. bRepeated positive for same respiratory virus in respiratory sample within 3 months. cEighty-two adult healthcare episodes with PCR unable to discriminate between rhinoviruses and enteroviruses due to cross reactivity in the PCR assay. These cases were included in the other viruses group but excluded from virus group-specific analyses. AdV, adenovirus; BoV, bocavirus; EV, enterovirus; MPV, metapneumoviruses; PIV, parainfluenzaviruses; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus; sCoV, seasonal coronavirus.

Patient characteristics and clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 compared with other respiratory viruses among adults

Adult patients with SARS-CoV-2 were younger and more often male (median age 58 years (IQR 42–71), 59% male) compared with influenza (median age 68 years (IQR 51–79), 48% male), RSV (median age 71 years (IQR 60–81), 44% male) and other viruses (median age 61 years (IQR 40–72), 56% male) (p<0.001) (table 1 and online supplemental eTable 4). After adjustment for sex and age, SARS-CoV-2 admission was associated with overweight and obesity, as well as lower CCI and ECI compared with influenza, RSV and other viruses (table 1). The only comorbidities that were over-represented among patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with influenza, RSV or other viruses were diabetes and hypertension.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in the different virus groups of the adult cohort

| Variable | Virus group (no. of healthcare episodes) | SARS-CoV-2 versus influenza | SARS-CoV-2 versus RSV | SARS-CoV-2 versus other viruses | ||||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | Influenza | RSV | Other viruses | OR (95% CI) |

aOR (95% CI)* |

OR (95% CI) |

aOR (95% CI)* |

OR (95% CI) |

aOR (95% CI)* |

|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||||||||

| Male sex, n (%) | 1010 (59) | 1194 (48) | 275 (44) | 840 (56) |

1.51

(1.34 to 1.71) |

– |

1.80

(1.50 to 2.17) |

– |

1.13

(0.98 to 1.30) |

– |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 58 (42–71) | 68 (51–79) | 71 (60–81) | 61 (40–72) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Age categories, n (%) | ||||||||||

| 16–39 | 377 (22) | 401 (16) | 36 (6) | 376 (25) | 0.89 (0.72 to 1.09) |

– |

2.34

(1.54 to 3.56) |

– |

0.61

(0.49 to 0.76) |

– |

| 40–49 | 212 (12) | 186 (8) | 33 (5) | 146 (10) | 1.07 (0.84 to 1.38) |

– | 1.43 (0.92 to 2.23) |

– | 0.88 (0.67 to 1.15) |

– |

| 50–59 | 345 (20) | 325 (13) | 77 (12) | 209 (14) | 1.0 (ref) | – | 1.0 (ref) | – | 1.0 (ref) | – |

| 60–69 | 334 (19) | 404 (16) | 130 (21) | 285 (19) |

0.78

(0.63 to 0.96) |

– |

0.57

(0.42 to 0.79) |

– |

0.71

(0.56 to 0.90) |

– |

| 70–79 | 209 (12) | 546 (22) | 167 (27) | 323 (21) |

0.36

(0.29 to 0.45) |

– |

0.28

(0.20 to 0.38) |

– |

0.39

(0.31 to 0.50) |

– |

| ≥80 | 244 (14) | 606 (25) | 181 (29) | 169 (11) |

0.38

(0.31 to 0.47) |

– |

0.30

(0.22 to 0.41) |

– | 0.87 (0.67 to 1.14) |

– |

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2§ | 27 (24–31) | 25 (22–29) | 25 (22–29) | 24 (21–28) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| BMI categories, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Normoweight (18.5–24.9)† | 529 (31) | 1062 (43) | 276 (44) | 711 (47) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 44 (3) | 137 (6) | 39 (6) | 128 (9) |

0.65

(0.44 to 0.96) |

0.67 (0.45 to 1.01) |

0.58

(0.35 to 0.94) |

0.59 (0.35 to 1.01) |

0.46

(0.31 to 0.69) |

0.47

(0.31 to 0.69) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 638 (37) | 772 (31) | 176 (28) | 412 (27) |

1.66

(1.42 to 1.95) |

1.55

(1.31 to 1.83) |

1.89

(1.50 to 2.38) |

1.68

(1.31 to 2.15) |

2.08

(1.74 to 2.49) |

2.06

(1.71 to 2.47) |

| Obese (≥30) | 510 (30) | 497 (20) | 132 (21) | 257 (17) |

2.06

(1.74 to 2.45) |

1.91

(1.60 to 2.28) |

2.01

(1.56 to 2.59) |

1.67

(1.28 to 2.19) |

2.67

(2.19 to 3.27) |

2.66

(2.16 to 3.26) |

| CCI, median (IQR), points | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CCI categories, n (%) | ||||||||||

| 0–1 | 1199 (70) | 1252 (51) | 235 (38) | 580 (38) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| 2–4 | 386 (22) | 890 (36) | 284 (46) | 675 (45) |

0.45

(0.39 to 0.52) |

0.52

(0.45 to 0.61) |

0.27

(0.22 to 0.33) |

0.39

(0.31 to 0.49) |

0.28

(0.24 to 0.32) |

0.24

(0.20 to 0.28) |

| ≥5 | 136 (8) | 326 (13) | 105 (17) | 253 (17) |

0.44

(0.35 to 0.54) |

0.50

(0.40 to 0.62) |

0.25

(0.19 to 0.34) |

0.36

(0.27 to 0.49) |

0.26

(0.21 to 0.33) |

0.22

(0.17 to 0.28) |

| ECI, median (IQR), points | 0 (0–6) | 5 (0–11) | 9 (3–14) | 7 (3–12) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ECI categories, n (%) | ||||||||||

| ≤0 | 947 (55) | 809 (33) | 104 (17) | 352 (23) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) |

| 1–10 | 493 (29) | 1005 (41) | 255 (41) | 613 (41) |

0.42

(0.36 to 0.48) |

0.46

(0.40 to 0.54) |

0.21

(0.16 to 0.27) |

0.28

(0.21 to 0.36) |

0.30

(0.25 to 0.35) |

0.26

(0.21 to 0.31) |

| ≥11 | 281 (16) | 654 (26) | 265 (42) | 543 (36) |

0.37

(0.31 to 0.43) |

0.43

(0.36 to 0.52) |

0.12

(0.09 to 0.15) |

0.17

(0.13 to 0.23) |

0.19

(0.16 to 0.23) |

0.15

(0.12 to 0.18) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus‡ | 392 (23) | 467 (19) | 107 (17) | 247 (16) |

1.26

(1.09 to 1.47) |

1.46

(1.24 to 1.71) |

1.43

(1.13 to 1.81) |

1.87

(1.46 to 2.41) |

1.51

(1.26 to 1.80) |

1.54

(1.28 to 1.85) |

| Hypertension‡ | 660 (38) | 907 (37) | 246 (39) | 413 (27) | 1.07 (0.94 to 1.22) |

1.68

(1.44 to 1.95) |

0.96 (0.79 to 1.15) |

2.10

(1.69 to 2.63) |

1.65

(1.42 to 1.92) |

1.95

(1.64 to 2.32) |

| Cardiac disease‡ | 403 (23) | 728 (29) | 237 (38) | 410 (27) |

0.73

(0.63 to 0.84) |

1.01 (0.86 to 1.18) |

0.50

(0.41 to 0.61) |

0.85 (0.68 to 1.06) |

0.82

(0.70 to 0.96) |

0.80

(0.67 to 0.96) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease‡ | 252 (15) | 518 (21) | 171 (27) | 328 (22) |

0.65

(0.55 to 0.76) |

0.79

(0.67 to 0.94) |

0.45

(0.36 to 0.57) |

0.66

(0.52 to 0.84) |

0.62

(0.51 to 0.74) |

0.63

(0.52 to 0.75) |

| Chronic kidney failure‡ | 133 (8) | 259 (10) | 86 (14) | 159 (11) |

0.71

(0.57 to 0.89) |

0.84 (0.67 to 1.05) |

0.52

(0.39 to 0.70) |

0.74 (0.54 to 1.00) |

0.71

(0.56 to 0.90) |

0.70

(0.55 to 0.90) |

| Malignancy‡ | 185 (11) | 537 (22) | 218 (35) | 606 (40) |

0.43

(0.36 to 0.52) |

0.46

(0.39 to 0.56) |

0.22

(0.18 to 0.28) |

0.27

(0.21 to 0.34) |

0.18

(0.15 to 0.22) |

0.17

(0.14 to 0.21) |

| Immunosuppression‡ | 314 (18) | 791 (32) | 295 (47) | 807 (54) |

0.47

(0.41 to 0.55) |

0.50

(0.43 to 0.58) |

0.25

(0.20 to 0.30) |

0.30

(0.24 to 0.37) |

0.19

(0.17 to 0.23) |

0.18

(0.15 to 0.21) |

| Any of the comorbidities above‡ | 1014 (59) | 1754 (71) | 513 (82) | 1199 (80) |

0.58

(0.51 to 0.66) |

0.72

(0.61 to 0.83) |

0.31

(0.25 to 0.39) |

0.54

(0.42 to 0.70) |

0.37

(0.32 to 0.43) |

0.27

(0.23 to 0.33) |

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

*Analyses were adjusted for age and sex.

†Normoweight defined as a BMI of 18.5–24.9, underweight <18.5, overweight 25–29.9, obese ≥30.

‡Based on ICD-10 codes from −5 years to +24 hours from admission time point. See list of ICD-10 codes for each comorbidity category in online supplemental table 1.

§Variable containing missing values, which were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations by predictive mean modelling. Descriptive data were calculated for each of the 50 imputed datasets, and the mean of each descriptive statistics is presented.

aOR, adjusted OR; BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; ECI, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Patients with SARS-CoV-2 more often presented with normal white cell count (WCC), platelet count and creatinine values (table 1, online supplemental eTable 5 and eFigure 2). In sex-adjusted and age-adjusted analyses, SARS-CoV-2 was associated with tachypnoea and less often hypotension or tachycardia, compared with all other virus groups, and less often fever (temperature >38°C) compared with influenza (online supplemental eTable 6 and eFigure 3). The prediction model that included age, sex, BMI, comorbidity, laboratory parameters and vital signs performed better compared with the simpler models, mean AUROC 0.74 for SARS-CoV-2 versus influenza, 0.83 for SARS-CoV-2 versus RSV and 0.82 for SARS-CoV-2 versus other viruses (online supplemental eFigure 4 and eTable 7).

Paediatric SARS-CoV-2 in relation to other respiratory viruses

Children with SARS-CoV-2 were older, while the sex distribution was similar compared with other respiratory viruses: SARS-CoV-2 median age 7 years (IQR 1–12), 55% male; influenza median age 2 years (IQR 0–5), 56% male; RSV median age 0 years (IQR 0–1), 56% male; and RV median age 1 year (IQR 0–3), 58% male (p<0.001 and 0.80) (table 2). The proportion of patients with at least one comorbidity differed between the viruses, being 20% (20/101) in SARS-CoV-2, 23% (198/871) in influenza and 16% (396/2425) in RSV, while it was higher (28%–43%) for the other viruses (p<0.001). Immunosuppression was the most prevalent comorbidity among patients with SARS-CoV-2 (10/101, 10%). Chronic respiratory disease, congenital malformations and chromosomal abnormalities were more prevalent in all nine other virus groups compared with SARS-CoV-2 (p<0.001). In the SARS-CoV-2 paediatric cohort, 41% presented with a temperature >38°C and 24% with increased respiratory rate or desaturation, which was lower than in all other virus groups (online supplemental eFigure 3). In children with SARS-CoV-2, the median LOS was 3 days (IQR 1–8), the 30-day and 90-day mortality were both 1% (1/101), 4% (4/101) were admitted to ICU and acute kidney injury based on modified KDIGO stage 1 criteria was detected in 8% (8/101).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of the paediatric cohort

| Baseline characteristics | Virus group (no. of healthcare episodes) | P value* | |||||||||

| SARS-CoV-2 (101) | Influenza (871) | RSV (2425) | RV (1413) | EV (99) |

PIV (359) | MPV (454) | sCoV (234) | AdV (238) | BoV (185) | ||

| Male sex | 55 (55) | 484 (56) | 1 362 (56) | 824 (58) | 57 (58) | 196 (55) | 267 (59) | 138 (59) | 141 (59) | 109 (59) | 0.80 |

| Age at admission, median (IQR), years | 7 (1–12) | 2 (0–5) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–2) | 2 (0–3) | 1 (0–4) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–2) | <0.001 |

| Age categories, n (%) | |||||||||||

| <1 | 25 (25) | 242 (28) | 1 673 (69) | 606 (43) | 44 (44) | 150 (42) | 135 (30) | 93 (40) | 52 (22) | 45 (24) | <0.001 |

| 1–4 | 20 (20) | 377 (43) | 689 (28) | 535 (38) | 38 (38) | 159 (44) | 242 (53) | 92 (39) | 151 (63) | 125 (68) | <0.001 |

| 5–15 | 56 (55) | 252 (29) | 63 (3) | 272 (19) | 17 (17) | 50 (14) | 77 (17) | 49 (21) | 35 (15) | 15 (8) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Prematurity and perinatal diseases† | 3 (3) | 61 (7) | 201 (8) | 168 (12) | 3 (3) | 45 (13) | 59 (13) | 36 (15) | 27 (11) | 25 (14) | <0.001 |

| Chronic cardiac disease† | 2 (2) | 27 (3) | 41 (2) | 75 (5) | 3 (3) | 22 (6) | 24 (5) | 18 (8) | 10 (4) | 11 (6) | <0.001 |

| Chronic respiratory disease† | 7 (7) | 170 (20) | 512 (21) | 414 (29) | 18 (18) | 101 (28) | 161 (35) | 70 (30) | 53 (22) | 63 (34) | <0.001 |

| Congenital malformations and chromosomal abnormalities† | 7 (7) | 107 (12) | 220 (9) | 263 (19) | 10 (10) | 65 (18) | 106 (23) | 53 (23) | 38 (16) | 36 (19) | <0.001 |

| Solid tumour† | 4 (4) | 16 (2) | 17 (1) | 64 (5) | 3 (3) | 10 (3) | 8 (2) | 13 (6) | 6 (3) | 6 (3) | <0.001 |

| Haematological malignancy† | 3 (3) | 19 (2) | 15 (1) | 68 (5) | 1 (1) | 7 (2) | 12 (3) | 15 (6) | 3 (1) | 6 (3) | <0.001 |

| Immunosuppression† | 10 (10) | 66 (8) | 57 (2) | 177 (13) | 5 (5) | 24 (7) | 29 (6) | 37 (16) | 20 (8) | 29 (16) | <0.001 |

| Any of the comorbidities above† | 20 (20) | 198 (23) | 396 (16) | 494 (35) | 16 (16) | 110 (31) | 157 (35) | 100 (43) | 66 (28) | 68 (37) | <0.001 |

| Outcomes | |||||||||||

| Length of stay, median (IQR), days | 3 (1–8) | 3 (2–4) | 4 (2–6) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 4 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–5) | <0.001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | |||||||||||

| 30 days‡ | 1 (1) | 6 (1) | 3 (0) | 15 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 6 (3) | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | <0.001 |

| 90 days§ | 1 (1) | 6 (1) | 4 (0) | 24 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 2 (0) | 7 (3) | 4 (2) | 6 (3) | <0.001 |

| ICU | |||||||||||

| ICU admitted, n (%)‡ | 4 (4) | 32 (4) | 146 (6) | 61 (4) | 4 (4) | 21 (6) | 35 (8) | 19 (8) | 16 (7) | 16 (9) | 0.009 |

| Length of ICU stay, median (IQR), days§ | 6 (4–6) | 1 (0–4) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–4) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–3) | 0.102 |

| Acute kidney injury, n (%)‡ | 8 (8) | 49 (6) | 43 (2) | 102 (7) | 3 (3) | 9 (3) | 20 (4) | 24 (10) | 12 (5) | 14 (8) | <0.001 |

| Hospital-onset bacteraemia, n (%)‡ | 2 (2) | 11 (1) | 14 (1) | 29 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 6 (1) | 9 (4) | 6 (3) | 2 (1) | <0.001 |

*Comparison of all virus groups using χ2 test for nominal and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

†Based on ICD-10 codes from −5 years to +24 hours from admission time point. See list of ICD-10 codes for each comorbidity category in online supplemental eTable 1.

‡Analysis restricted to patients with a minimum of 30-day follow-up time, that is, patients admitted until 1 September 2020. SARS-CoV-2 (99), influenza (871), RSV (2 425), RV (1380), EV (98), PIV (359), MPV (454), sCoV (234), AdV (238) and BoV (184).

§Analysis restricted to patients with a minimum of 90-day follow-up time, that, patients admitted until 1 July 2020. SARS-CoV-2 (81), influenza (871), RSV (2425), RV (1356), EV (98), PIV (359), MPV (454), sCoV (234), AdV (238) and BoV (183).

¶Analysis restricted to ICU-admitted patients. SARS-CoV-2 (4), influenza (32), RSV (146), RV (61), EV (4), PIV (21), MPV (35), sCoV (19), AdV (16) and BoV (16).

AdV, adenovirus; BoV, bocavirus; EV, enterovirus; ICU, intensive care unit; MPV, metapneumovirus; PIV, parainfluenzavirus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus; sCoV, seasonal coronaviruses.

Clinical outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 compared with other respiratory viruses among adults

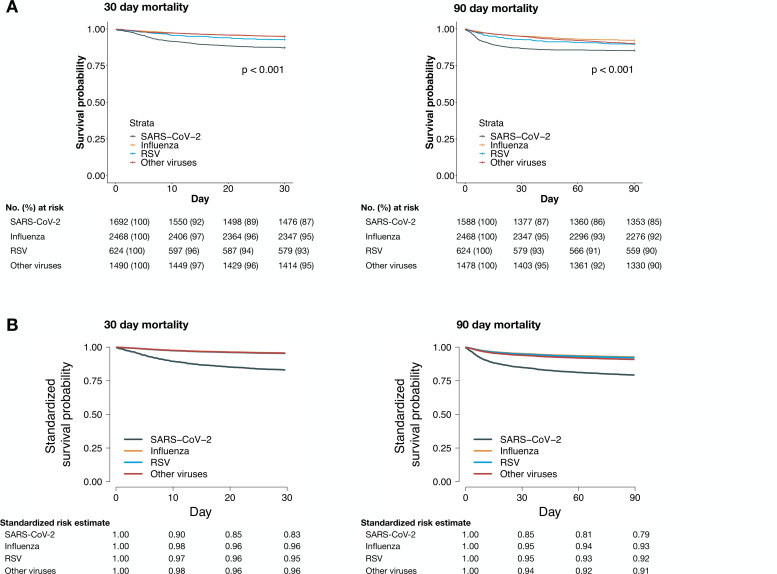

The LOS in patients with SARS-CoV-2 was longer (6 days (IQR 3–11)) compared with influenza (4 days (IQR 2–7)), RSV (5 days (IQR 3–9)) and other viruses (4 days (IQR 2–8)). The 30-day mortality was 13% among patients with SARS-CoV-2 as compared with 5% for influenza, 7% for RSV and 5% for the other virus group (table 3 and figure 2). The adjusted 30-day mortality HR (aHR) for SARS-CoV-2 was 4.43 (95% CI 3.51 to 5.59), 3.81 (95% CI 2.72 to 5.34) and 3.46 (95% CI 2.61 to 4.60) compared with influenza, RSV and other viruses, respectively. This resulted in the following standardised 30-day survival probabilities: SARS-CoV-2 0.83 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.87), influenza 0.96 (95% CI 0.95 to 0.97), RSV 0.95 (95% CI 0.94 to 0.97) and other viruses 0.96 (95% CI 0.95 to 0.97) (figure 2). The SARS-CoV-2 30-day mortality was 16% (154/981) from February to April 2020 and 8% (62/740) from May to September 2020. For patients with SARS-CoV-2 admitted from May to September 2020, the 30-day mortality aHR compared with influenza, RSV and other viruses were 3.09 (95% CI 2.22 to 4.30), 3.00 (95% CI 1.95 to 4.62) and 2.60 (95% CI 1.79 to 3.80) (online supplemental eTable 8). In analyses stratified by age, the 30-day mortality aHR for patients aged 70 years or older was 5.41 (95% CI 4.17 to 7.00), 4.93 (95% CI 3.37 to 7.23) and 5.03 (95% CI 3.61 to 7.01) in patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with influenza, RSV and other viruses, respectively (online supplemental eTable 9). The corresponding aHR for patients aged 50–69 years were 2.16 (95% CI 1.31 to 3.57), 1.71 (95% CI 0.81 to 3.60) and 2.07 (95% CI 1.13 to 3.79). The excess mortality in patients with SARS-CoV-2 occurred in the first 30 days, and in adjusted analyses, there was no significantly increased mortality risk among patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with the other virus groups from day 31 to day 90 (online supplemental eFigure 5).

Table 3.

Outcomes for SARS-CoV-2 versus influenza, RSV and other viruses in the adult cohort

| Outcome variable | Virus group (no. of healthcare episodes) | SARS-CoV-2 versus influenza | SARS-CoV-2 versus RSV | SARS-CoV-2 vs other viruses | ||||||

| SARS-CoV-2 (1721) | Influenza (2468) | RSV (624) | Other viruses (1508) | Unadjusted ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted ratio (95% CI)* |

Unadjusted ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted ratio (95% CI)* |

Unadjusted ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted ratio (95% CI)* |

|

| Length of stay, median (IQR)† | 6 (3–11) | 4 (2–7) | 5 (3–9) | 4 (2–8) |

1.53

(1.43 to 1.64) |

1.47

(1.37 to 1.58) |

1.38

(1.25 to 1.53) |

1.37

(1.22 to 1.53) |

1.35

(1.25 to 1.46) |

1.30

(1.19 to 1.41) |

| Mortality | ||||||||||

| Days 0–30, n (%)§¶ |

216 (13) | 121 (5) | 45 (7) | 76 (5) |

2.73

(2.18 to 3.41) |

4.43

(3.51 to 5.59) |

1.83

(1.33 to 2.53) |

3.81

(2.72 to 5.34) |

2.62

(2.02 to 3.40) |

3.46

(2.61 to 4.60)‡ |

| Days 0–90, n (%)§** |

235 (15) | 192 (8) | 65 (10) | 148 (10) |

2.02

(1.67 to 2.44)‡ |

3.34

(2.73 to 4.08)‡ |

1.48

(1.13 to 1.95)‡ |

3.13

(2.34 to 4.18)‡ |

1.56

(1.27 to 1.92)‡ |

2.28

(1.82 to 2.86)‡ |

| Days 31–90, n (%)§†† |

24 (2) | 71 (3) | 20 (4) | 73 (5) |

0.57

(0.36 to 0.91)‡ |

0.98 (0.60 to 1.59) |

0.50

(0.28 to 0.91) |

1.14 (0.59 to 2.19) |

0.33

(0.21 to 0.52)‡ |

0.62 (0.37 to 1.03) |

| Intensive care | ||||||||||

| ICU admission, n (%)§¶ |

294 (17) | 244 (10) | 72 (12) | 167 (11) |

1.70

(1.43 to 2.01)‡ |

1.46

(1.22 to 1.75)‡ |

1.52

(1.18 to 1.97)‡ |

1.28

(0.96 to 1.69)‡ |

1.53

(1.27 to 1.85)‡ |

1.32

(1.07 to 1.64)‡ |

| ICU length of stay, median (IQR)††† | 4 (1–11) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–4) | 1 (0–4) |

2.17

(1.64 to 2.85) |

2.24

(1.68 to 3.00) |

2.48

(1.70 to 3.56) |

1.99

(1.32 to 3.00) |

3.22

(2.42 to 4.26) |

2.80

(2.02 to 3.87) |

| 30-day mortality in ICU-admitted cohort, n (%)§†† |

77 (26) | 47 (19) | 18 (25) | 23 (14) | 1.42 (0.98 to 2.03) |

2.40

(1.58 to 3.64) |

1.04 (0.62 to 1.74) |

2.87

(1.55 to 5.33) |

2.07

(1.30 to 3.30) |

3.75

(2.15 to 6.54) |

| Acute myocardial injury, n (%)§¶ | 253 (15) | 250 (10) | 71 (11) | 151 (10) |

1.25

(1.05 to 1.49)‡ |

1.42

(1.18 to 1.71)‡ |

1.14 (0.88 to 1.49)‡ |

1.58

(1.19 to 2.09)‡ |

1.34

(1.09 to 1.63)‡ |

1.17 (0.94 to 1.46)‡ |

|

Acute kidney injury,

n (%)§¶ |

286 (17) | 333 (14) | 82 (13) | 228 (15) | 0.93 (0.80 to 1.09) |

0.77

(0.65 to 0.91)‡ |

1.14 (0.89 to 1.46)‡ |

1.11 (0.85 to 1.45)‡ |

0.94

(0.79 to 1.11) |

0.86 (0.70 to 1.05)‡ |

|

Pulmonary embolism,

n (%)‡‡§§ |

83 (5) | 32 (1) | 8 (1) | 35 (2) |

3.93

(2.63 to 6.01) |

5.26

(3.34 to 8.28) |

3.97

(2.03 to 8.96) |

6.23

(2.82 to 13.76) |

2.14

(1.45 to 3.24) |

3.34

(2.06 to 5.40) |

|

Hospital-onset bacteraemia,

n (%)§¶ |

92 (5) | 46 (2) | 16 (3) | 52 (3) |

1.86

(1.30 to 2.65) |

1.43 (0.98 to 2.09) |

1.55 (0.91 to 2.64) |

1.27 (0.70 to 2.31)‡ |

1.14 (0.81 to 1.61) |

1.10 (0.73 to 1.64) |

Bold values indicate statistical significance.

*The regression models were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, chronic cardiac disease, chronic respiratory disease, chronic kidney disease, malignancy and immunosuppression.

†Analysed by a negative binomial regression model.

‡Violation of proportional hazards assumption (Schoenfeld individual test, p value <0.05).

§Analysed by a Cox regression model.

¶Analysis restricted to patients with a minimum of 30-day follow-up time, that is, patients admitted until 1 September 2020. SARS-CoV-2 (1692), influenza (2 468), RSV (624) and other viruses (1490).

**Analysis restricted to patients with a minimum of 90-day follow-up time, that is, patients admitted until 1 July 2020. SARS-CoV-2 (1 588), influenza (2 465), RSV (624) and other viruses (1478).

††Analysis restricted to ICU-admitted patients. SARS-CoV-2 (294), influenza (244), RSV (72) and other viruses (167).

‡‡Analysed by a logistic regression model.

§§Analysis restricted to the current healthcare episode, with only finished episodes included. SARS-CoV-2 (1719), influenza (2468), RSV (624) and other viruses (1508).

BMI, body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves (A) and standardised survival function curves (B) for mortality by virus group. (A) Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier curves and risk tables for 30-day (left) and 90-day (right) mortality. P value represents result of significance testing using log-rank tests. The 30-day mortality Kaplan-Meier curves for the influenza and other viruses groups overlap. (B) Complete case-based standardised survival functions for 30-day (left) and 90-day (right) mortality. For 30-day mortality, complete data were available for 1272 SARS-CoV-2, 2220 influenza, 591 RSV and 1386 other viruses healthcare episodes. For 90-day mortality, complete data were available for 1194 SARS-CoV-2, 2118 influenza, 555 RSV and 1315 other viruses healthcare episodes. The survival functions were all standardised and adjusted for sex, age, BMI category, diabetes, hypertension, cardiac disease, respiratory disease, chronic kidney disease and malignancy as presented in table 1. The 30-day mortality curves for the influenza, RSV and other viruses groups overlap. AdV, adenovirus; BMI, body mass index; BoV, bocavirus; EV, enterovirus; MPV, metapneumoviruses; PIV, parainfluenzaviruses; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RV, rhinovirus; sCoV, seasonal coronavirus.

Patients with SARS-CoV-2 had an increased risk of ICU admission as compared with influenza and other viruses (table 3). The ICU LOS was longer, and the 30-day mortality after ICU admission was higher for patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with all other virus groups. SARS-CoV-2 was associated with an increased risk of pulmonary embolism, adjusted ORs 5.26 (95% CI 3.34 to 8.28), 6.23 (95% CI 2.82 to 13.76) and 3.34 (95% CI 2.06 to 5.40) compared with influenza, RSV and other viruses, respectively, and also AMI compared with influenza and RSV, aHR 1.42 (95% CI 1.18 to 1.71) and 1.58 (95% CI 1.19 to 2.09), respectively. A decreased risk of AKI was observed for SARS-CoV-2 compared with influenza. For HOB, no significant risk differences were observed in adjusted analyses. The increased SARS-CoV-2 HR for mortality and ICU admission were consistent across sensitivity analyses (online supplemental eTable 8), but with more favourable outcomes for the SARS-CoV-2 cohort admitted from May to September 2020 as compared with February–April 2020. Adjusted mortality HRs were similar for analyses based on complete cases and multiple imputed data, and no significant difference was observed in 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality or ICU admission between 2015–2020 and 2011–2014 for influenza, RSV as well as other viruses (online supplemental eTable 10 and eFigure 6).

Discussion

This observational study of 12 700 adult and paediatric admissions to a University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden, showed that although SARS-CoV-2 was associated with younger age in adults and an overall lower comorbidity burden, there was a marked increased risk of 30-day mortality, ICU admission, ICU mortality and pulmonary embolism compared with other respiratory viruses. The mortality increase was most pronounced among the elderly and was attenuated during the later part of the study period, possibly due to improved management of patients with SARS-CoV-2. These findings were consistent across sensitivity analyses, considering potential change over time in diagnostic procedures, patient management and clinical presentation at admission, which highlights important differences in healthcare demands between SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory viruses.

Combined with data from others studies, our results indicate substantial differences in outcomes for patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with other respiratory viruses. In a study from Denmark where SARS-CoV-2 positive patients were compared with influenza, the unadjusted 30-day mortality was three times higher for patients with SARS-CoV-2, and a study from the UK comparing two cohorts of ICU patients admitted with diagnostic codes of COVID-19 and other respiratory viruses reported an almost doubled mortality in the COVID-19 cohort.19 20 A French study based on diagnostic codes reported a three times increased in-hospital mortality in 89 530 patients with COVID-19 compared with 45 819 patients with influenza, with the risk increase being more pronounced for patients aged ≥60 years.21

A study based on data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare system, with 95% of patients being male, reported a five times higher mortality in patients with COVID-19 compared with influenza.22 These studies corroborate our findings of a threefold and fourfold increased 90-day and 30-day mortality in patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with patients hospitalised with influenza or RSV.

Previous case series have demonstrated cardiac and circulatory complications in COVID-19, with reported acute myocardial injury incidence between 7% and 40% in hospitalised patients and 2%–9% developing pulmonary embolism.23–27 However, acute cardiovascular events have also been associated with influenza and RSV, and previous studies based on diagnostic codes reported higher proportion of influenza patients developing cardiovascular complications as compared with patients with COVID-19.21 28–30 In our study, SARS-CoV-2 was associated with an increased risk of troponin-defined acute myocardial injury compared with influenza and RSV, and there was a 3–5 fold increased risk of pulmonary embolism in patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with the other virus groups. This is concordant with studies from Denmark, France and the USA that reported an increased risk of thromboembolic events in patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with influenza.19 21 30 Yet, retrospective studies comparing thromboembolic and cardiac events in patients with COVID-19 compared with other viruses might suffer from bias since they rely on ICD-10 discharge codes as well as likely differential testing strategies in patients with COVID-19. In our study, troponin T was assessed in 65% of SARS-CoV-2 compared with 27% and 29% in influenza and RSV patients. Also, elevated troponin might indicate myocarditis that has been associated with COVID-19, rather than ischaemic heart disease.21

Male sex, overweight, obesity, diabetes and hypertension were more common in patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared with the other respiratory viruses, which strengthen evidence that these are risk factors for hospitalisation with COVID-19.5 6 31 32 Yet, the overall comorbidity burden of patients with SARS-CoV-2, as measured by CCI and ECI scores, were lower. Patients with SARS-CoV-2 in our study were somewhat younger than reported from other cohorts, which was adjusted for in the analyses.19 30 The younger age distribution could partly be explained by differences in the affected patient populations and hospitalisation patterns during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Few studies have directly compared with what extent clinical presentation at admission can be used to differentiate SARS-CoV-2 from other respiratory viruses, and current evidence is based on studies of small sample sizes.4 5 33 34 Patients with SARS-CoV-2 more often presented with normal haemodynamic measurements, WCC, platelet count and creatinine values and were more often tachypnoeic. No clear difference was observed for saturation, measured as worst peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2), or when accounting for oxygen treatment using the SpO2/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio. Prediction models of increased complexity, although increasing in performance, demonstrated limited virus discriminating capability, for example, model 3 resulted in 60% sensitivity and 80% specificity to differentiate between SARS-CoV-2 and influenza. Future prospective studies should assess if symptoms and laboratory tests such as ferritin and interleukin-6 are associated with SARS-CoV-2 compared with other viruses.35

Among children, no difference in sex distribution was observed, whereas patients with SARS-CoV-2 were older compared with other respiratory viruses in line with a previous study that reported patients with COVID-19 to be older compared with patients with influenza.21 Paediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2 were more likely to present without an increased body temperature and dyspnoea, possibly due to more frequent screening of SARS-CoV-2 compared with other respiratory viruses. Paediatric patients with SARS-CoV-2 had a lower prevalence of chronic respiratory diseases and congenital malformations compared with other viruses. Severe outcomes were rare in the paediatric cohort.

Strengths of our study include the large study size, similar strict inclusion criteria regardless of viral infections and ample access to clinical data that enabled thorough analyses of clinical phenotype as well as adjustment for confounding. The strict virological inclusion criteria increased the internal validity of the study and reduced the risk of including patients transferred from other hospitals to the Karolinska University Hospital, which was more common during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Even though the study population comprised a large portion of consecutively admitted patients with viral infections in the Stockholm region during a 9-year period, to verify generalisability, confirmation of the findings is warranted in patients from other geographical regions and hospitals. Data were collected from patient records, which depends on correct entry by healthcare staff. Yet, the risk of misclassification is likely independent of type of respiratory infections, and we restricted our analysis to routinely collected data. To increase internal validity, we restricted the analyses to episodes positive for only one virus, which might hamper the generalisability to all patients positive with respiratory virus. Yet, this would have minor impact on the results among adults since we only excluded 1.8% of admissions. Indications for SARS-CoV-2 testing might have differed compared with other respiratory viruses. Yet, the results were robust in sensitivity analyses restricting the study population to patients with fever, reduced oxygen saturation or increased respiratory rate at admission. However, the results for other viruses than SARS-CoV-2, influenza and RSV need to be interpreted with caution due to differential testing indications. Finally, due to the pandemic, hospitalisation patterns in different age groups, length of stay and ICU admission criteria might differ compared with the earlier study period.

Conclusion

SARS-CoV-2 is associated with an increased risk of mortality, ICU admission and pulmonary embolism in hospitalised patients compared with influenza, RSV and other respiratory viruses. Although SARS-CoV-2 is associated with specific patient and clinical characteristics at admission compared with other respiratory viruses, substantial overlap precludes discrimination based on these characteristics.

Footnotes

Contributors: PH, HT and SvdW had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: PH, AF, MB, AT and PN. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: PH, JKV, SvdW, HT, ARM, JM, RD and OH. Drafting of the manuscript: PH nd PN. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: PH and FG. Additional contributions: none.

Funding: The work was supported by grants from the Swedish Innovation Agency (Vinnova) and Region Stockholm. PH was supported by Karolinska Institutet (combined clinical studies and PhD training programme). JKV was supported by Region Stockholm (combined clinical residency and PhD training programme).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available. Data from deidentified electronic health records are not freely available due to protection of the personal integrity of the participants.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Dnr 2018/1030-31, COVID-19 research amendment Dnr 2020–01385).

References

- 1. Burke RM, Killerby ME, Newton S, et al. Symptom profiles of a convenience sample of patients with COVID-19 - United States, January-April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:904–8. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6928a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, et al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 2020;324:782–93. 10.1001/jama.2020.12839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnstone J, Majumdar SR, Fox JD, et al. Viral infection in adults hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: prevalence, pathogens, and presentation. Chest 2008;134:1141–8. 10.1378/chest.08-0888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the new York City area. JAMA 2020;323:2052–9. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 2020;369:m1985–12. 10.1136/bmj.m1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burn E, You SC, Sena AG, et al. Deep phenotyping of 34,128 adult patients hospitalised with COVID-19 in an international network study. Nat Commun 2020;11:1–11. 10.1038/s41467-020-18849-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bompard F, Monnier H, Saab I, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2020;56:2001365–20. 10.1183/13993003.01365-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kolhe NV, Fluck RJ, Selby NM, et al. Acute kidney injury associated with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003406. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Viner RM, Mytton OT, Bonell C, et al. Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection among children and adolescents compared with adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175:1–14. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.4573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liguoro I, Pilotto C, Bonanni M, et al. SARS-COV-2 infection in children and newborns: a systematic review. Eur J Pediatr 2020;179:1029–46. 10.1007/s00431-020-03684-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1663–5. 10.1056/NEJMc2005073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zachariah P, Johnson CL, Halabi KC, et al. Epidemiology, clinical features, and disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a children's hospital in New York City, New York. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174:e202430. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Looi M-K. Covid-19: is a second wave hitting Europe? BMJ 2020;371:m4113. 10.1136/bmj.m4113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Belongia EA, Osterholm MT. COVID-19 and flu, a perfect storm. Science 2020;368:1163. 10.1126/science.abd2220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sjölander A. Regression standardization with the R package stdReg. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:563–74. 10.1007/s10654-016-0157-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kellum JA, Lameire N, Aspelin P. Kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2012;2:1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Valik JK, Ward L, Tanushi H, et al. Validation of automated sepsis surveillance based on the Sepsis-3 clinical criteria against physician record review in a general Hospital population: observational study using electronic health records data. BMJ Qual Saf 2020;29:735–45. 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tiveljung-Lindell A, Rotzén-Ostlund M, Gupta S, et al. Development and implementation of a molecular diagnostic platform for daily rapid detection of 15 respiratory viruses. J Med Virol 2009;81:167–75. 10.1002/jmv.21368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nersesjan V, Amiri M, Christensen HK, et al. Thirty-Day mortality and morbidity in COVID-19 positive vs. COVID-19 negative individuals and vs. individuals tested for influenza A/B: a population-based study. Front Med 2020;7:1–10. 10.3389/fmed.2020.598272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richards-Belle A, Orzechowska I, Gould DW, et al. COVID-19 in critical care: epidemiology of the first epidemic wave across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:2035–47. 10.1007/s00134-020-06267-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Piroth L, Cottenet J, Mariet A. Articles comparison of the characteristics, morbidity, and mortality of COVID-19 and seasonal influenza : a nationwide, population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir 2020;2600:1–9. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30527-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xie Y, Bowe B, Maddukuri G, et al. Comparative evaluation of clinical manifestations and risk of death in patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 and seasonal influenza: cohort study. BMJ 2020;371:1–12. 10.1136/bmj.m4677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lala A, Johnson KW, Januzzi JL, et al. Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:533–46. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:802. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fauvel C, Weizman O, Trimaille A, et al. Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: a French multicentre cohort study. Eur Heart J 2020;41:3058–68. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giustino G, Pinney SP, Lala A, et al. Coronavirus and cardiovascular disease, myocardial injury, and arrhythmia: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2011–23. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sakr Y, Giovini M, Leone M, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: a narrative review. Ann Intensive Care 2020;10:124. 10.1186/s13613-020-00741-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chow EJ, Rolfes MA, O'Halloran A, et al. Acute cardiovascular events associated with influenza in hospitalized adults : a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:605–13. 10.7326/M20-1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ivey KS, Edwards KM, Talbot HK. Respiratory syncytial virus and associations with cardiovascular disease in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1574–83. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cates J, Lucero-Obusan C, Dahl RM, et al. Risk for in-hospital complications associated with COVID-19 and influenza - veterans health administration, United States, October 1, 2018-May 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1528–34. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guan W-jie, Liang W-hua, Zhao Y, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J 2020;55. 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peckham H, de Gruijter NM, Raine C, et al. Male sex identified by global COVID-19 meta-analysis as a risk factor for death and ITU admission. Nat Commun 2020;11:6317. 10.1038/s41467-020-19741-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zayet S, Kadiane-Oussou N'dri Juliette, Lepiller Q, et al. Clinical features of COVID-19 and influenza: a comparative study on Nord Franche-Comte cluster. Microbes Infect 2020;22:481–8. 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tang X, Du R-H, Wang R, et al. Comparison of hospitalized patients with ARDS caused by COVID-19 and H1N1. Chest 2020;158:195–205. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kox M, Waalders NJB, Kooistra EJ, et al. Cytokine levels in critically ill patients with COVID-19 and other conditions. JAMA 2020;324:1565–7. 10.1001/jama.2020.17052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

thoraxjnl-2021-216949supp001.pdf (3.9MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. Data from deidentified electronic health records are not freely available due to protection of the personal integrity of the participants.