Abstract

Background

Laboratory tests are a mainstay in managing the COVID-19 pandemic, and high hopes are placed on rapid antigen tests. However, the accuracy of rapid antigen tests in real-life clinical settings is unclear because adequately designed diagnostic accuracy studies are essentially lacking.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to assess the accuracy of a rapid antigen test in diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection in a primary/secondary care testing facility.

Methods

Consecutive individuals presenting at a COVID-19 testing facility affiliated to a Swiss University Hospital were recruited (n = 1465%). Nasopharyngeal swabs were obtained, and the Roche/SD Biosensor rapid antigen test was conducted in parallel with two real-time PCR tests (reference standard).

Results

Among the 1465 patients recruited, RT-PCR was positive in 141 individuals, corresponding to a prevalence of 9.6%. The Roche/SD Biosensor rapid antigen test was positive in 94 patients (6.4%), and negative in 1368 individuals (93.4%; insufficient sample material in 3 patients). The overall sensitivity of the rapid antigen test was 65.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] 56.8–73.1), the specificity was 99.9% (95% CI 99.5–100.0). In asymptomatic individuals, the sensitivity was 44.0% (95% CI 24.4–65.1).

Conclusions

The accuracy of the SARS-CoV-2 Roche/SD Biosensor rapid antigen test in diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infections in a primary/secondary care testing facility was considerably lower compared with the manufacturer's data. Widespread application in such a setting might lead to a considerable number of individuals falsely classified as SARS-CoV-2 negative.

Keywords: infections, epidemiology, transmission, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, COVID-19 diagnostic testing

Background

Governments worldwide are pinning high hopes on COVID-19 testing programs using rapid antigen tests to ease the burden on healthcare systems and lift restrictions that have disrupted workplaces and led to pervasive socio-economic costs (Crozier et al., 2021; Dinnes et al., 2020). In contrast with a standard laboratory-based reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test, rapid antigen tests require much less technical expertise and laboratory capacity (Mattiuzzi et al., 2020). As point-of-care devices, these tests can be performed by minimally trained persons in various primary and even community settings (Dinnes et al., 2020). Moreover, test results are delivered within 5–30 minutes and are available within a single clinical encounter (Mattiuzzi et al., 2020). Thus, rapid antigen tests might overcome the drawbacks of RT-PCR in terms of availability, throughput, and turnaround time (Mattiuzzi et al., 2020). These limitations of RT-PCR are recognized as a major barrier to the broad implementation of urgent testing capabilities for everybody (Iacobucci, 2020; Mattiuzzi et al., 2020; Thornton, 2020). Thus, rapid antigen tests might support the almost universal strategy of early diagnosis and timely isolation of individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection (Mattiuzzi et al., 2020).

Early diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection and timely isolation are most often addressed by testing individuals with symptoms or known exposure to patients (Dinnes et al., 2020). Testing facilities aiming to confirm or rule out SARS-CoV-2 infection in this population are affiliated with various primary or secondary care facilities. More recently, tests are being provided in the community setting, and even self-testing is being applied. As a prerequisite, applied laboratory tests must be accurate to be of value in such settings (Dinnes et al., 2020). This means that the number of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection missed by the respective laboratory test (false-negatives) must be low. Accordingly, the number of individuals falsely claimed to be infected (false-positives) must also be low.

Performance measures relate to the diagnostic accuracy of a test, which can only be determined in an adequately designed diagnostic accuracy study (Bossuyt et al., 2015; Bossuyt, 2007; Crozier et al., 2021; Dinnes et al., 2020; Mallett et al., 2012; Whiting et al., 2011). To assess the accuracy of a rapid antigen test in diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection in a secondary or primary care testing facility, diagnostic accuracy studies need to be conducted in defined clinical settings. To date, such studies are essentially lacking (Dinnes et al., 2020).

Our prospective cross-sectional study aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of a rapid antigen test in diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection in a primary/secondary care testing facility.

Methods

Study design, setting, and population

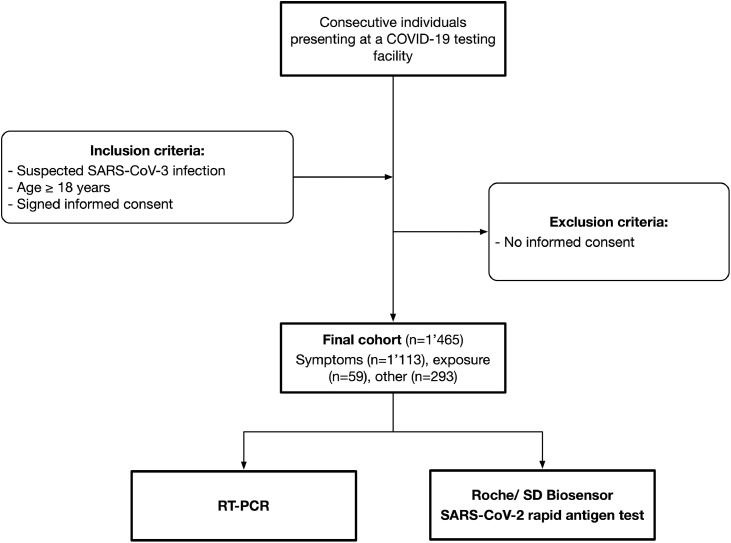

The AgiP study was a prospective cross-sectional study conducted at a COVID-19 testing facility affiliated to a Swiss university hospital. Consecutive individuals presenting on their own between January and March 2021 were recruited. Inclusion criteria were: (a) suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection; (b) age ≥ 18 years; and (c) signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria were clinical warning signs that required emergency medical care (CDC, 2020). A flow chart of the patient selection process is given in Figure 1 . The COVID-19 testing facility is one of the largest testing facilities in the greater Bern area, affiliated to a large, specialized laboratory running high-troughput RT-PCR (Brigger et al., 2021). During the study period, individuals were instructed by the authorities to present themselves when experiencing symptoms consistent with SARS-CoV-2. The authorities also referred patients suspected of exposure to infected individuals. Some individuals presented for other reasons (e.g. travel requirements or for shortening quarantine measures). The study protocol was approved by the appropriate ethical committee (Kantonale Ethikkommission Bern #2020-02729) and the institutional authorities. All participants signed informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the patient selection process.

Study processes, handling of data, and samples

Individuals were recruited and informed by specially trained medical staff before the consultation. Following informed consent, patients completed a questionnaire, which was created according to Swiss Federal Office of Public Health guidelines and the recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (CDC, 2020; FOPH, 2021a). Acute respiratory syndrome was defined as a new onset of respiratory illness symptoms (sore throat, cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain) (FOPH, 2021a). Additional symptoms were fever, muscle or body aches, loss of taste or smell, confusion, or poor general condition. During the subsequent consultation, the answers to the questionnaire were checked by a specialist physician. Nasopharyngeal specimens were collected by a specially trained nurse. All nurses had completed a training course that was prepared according to established guidelines on swab collection (CDC, 2021). Nurses were supervised during the first few days of practice. Swabs were collected using iClean Specimen Collection Flocked Swabs (Cleanmo Technology Co., Shenzhen, China) and Liofilchem Viral Transport Medium (Italy). Sample material was stored at 4°C and processed within 6 hours (antigen test) or 12 hours (RT-PCR). Coded clinical data and laboratory test results were stored in separate databases and merged before analysis.

Determination of the rapid antigen test

Using the same sample material, the Roche/SD Biosensor SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen test was conducted in parallel by a trained medical laboratory technician (unaware of the RT-PCR results). Quality control was performed daily, and the manufacturer's instructions were strictly followed (package leaflet; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). In brief, three drops of the extracted sample were applied to the specimen well of the test device and the test result was recorded after 15–30 minutes. The result was only considered valid if the control line was visible. Even faint test lines were considered positive.

Determination of real-time PCR

As a reference standard test confirming the presence of COVID-19, two real-time PCR (RT-PCR) assays were conducted, as previously described (Roche cobas® SARS-CoV-2; Seegene Allplex 2019-nCoV) (Brigger et al., 2021). Analyses were performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions on a STARlet IVD System or a cobas 8800 system. RT-PCR was carried out in line with clinical practice, with laboratory technicians unaware of the index test results. Detectable SARS-CoV-2 below or at a cycle threshold of 40 were considered positive. Commercially available quality control was conducted with each test run.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were presented as numbers (percentages) or mean (standard deviation), as appropriate. Two-by-two tables were created using RT-PCR results as the reference standard test and the Roche/SD Biosensor as the index test. Sensitivities and specificities were calculated accordingly. Data were presented overall and in salient subgroups. For sensitivity analysis, diagnostic accuracy measures were calculated for additional cycling thresholds (CT) of the RT-PCR. A method proposed by Bujang et al. was used for the power analysis (Bujang and Adnan, 2016). A prevalence of 10% and a power of 0.8 were considered as verifying sensitivity of 90%. Confidence intervals were also calculated. Analyses were performed using the Stata 14.2 statistical software (StataCorp., 2014, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

In total, 1465 individuals were eventually included (Figure 1). The majority of patients presented with symptoms consistent with COVID-19 (n = 1114; 76.0%). Fifty-nine individuals were referred because of exposure to infected individuals (4.0%). Other reasons (e.g. travel requirements) accounted for 293 patients (20.0%). The mean age was 36.4 years (standard deviation, SD 14.0); 787 individuals (53.7%) were female. Detailed patient characteristics are given in Table 1 . Three individuals provided insufficient sample material for determination of the rapid antigen test.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 1465 study participants presenting at a COVID-19 testing facility affiliated to the emergency department of a university hospital. *For example, travel requirements or for shortening quarantine measures; +defined as a new onset of respiratory illness symptoms (sore throat, cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain). Abbreviations: RT-PCR, real-time PCR; SD, standard deviation.

| No. (%) | |||

| Characteristic | Overall | RT-PCR negative | RT-PCR positive |

| No. | 1’465 (100) | 1’324 (90.4) | 141 (9.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 36.4 (14.0) | 36.5 (14.0) | 35.7 (13.7) |

| Female | 787 (53.7) | 708 (53.5) | 79 (56.0) |

| Reason for testing | |||

| Symptoms | 1114 (76.0) | 997 (75.3) | 116 (82.3) |

| Exposure to infected individuals | 59 (4.0) | 52 (3.9) | 7 (5.0) |

| Other* | 293 (20.0) | 275 (20.8) | 18 (12.8) |

| Presence of symptoms | |||

| Any symptom | 1114 (76.0) | 998 (75.4) | 116 (82.3) |

| Acute respiratory syndrome+ | 521 (35.6) | 482 (36.4) | 39 (27.7) |

| Fever | 491 (33.5) | 426 (32.2) | 65 (46.1) |

| Loss of smell and taste | 54 (3.7) | 45 (3.4) | 9 (6.4) |

| Billing | |||

| Government | 1178 (80.4) | 1055 (79.7) | 123 (87.2) |

| Self-payer | 256 (17.5) | 239 (18.1) | 17 (12.1) |

| Unknown | 31 (2.1) | 30 (2.3) | 1 (0.7) |

In total, 141 individuals tested positive according to RT-PCR, corresponding to a prevalence of 9.6%. Complete agreement between both RT-PCR assays was observed. The Roche/SD Biosensor rapid antigen test was positive in 94 patients (6.4%), and negative in 1368 individuals (93.4%).

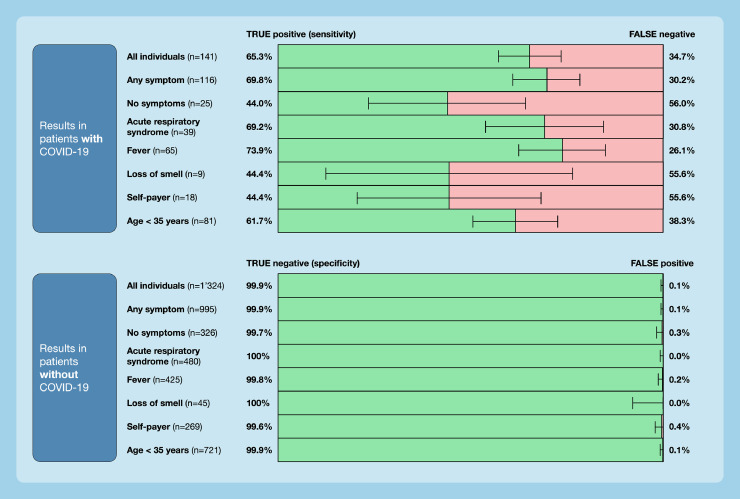

The overall sensitivity of the Roche/SD Biosensor rapid antigen test was 65.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] 56.8–73.1); the specificity was 99.9 (95% CI 99.5–100.0). The number of false-negative test results was 49, and the number of false-positives was 2 (n = 92 true positives; n = 1319 true negatives). The sensitivity of the rapid antigen test was higher in patients with any symptom (69.8%), acute respiratory syndrome (69.2%), and fever (73.9%). The sensitivity was lower in asymptomatic individuals (44%) and other subgroups. Details of sensitivities and specificities according to age group, presence of symptoms, or billing mode are presented in Figure 2 .

Figure 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of the Roche/SD Biosensor rapid antigen test in a real-life clinical setting. 1465 consecutive individuals presenting at a COVID-19 testing facility affiliated to a university hospital between January and March 2021 were studied. Sensitivities and specificities are in relation to RT-PCR, and are given for the overall study group as well as for salient subgroups.

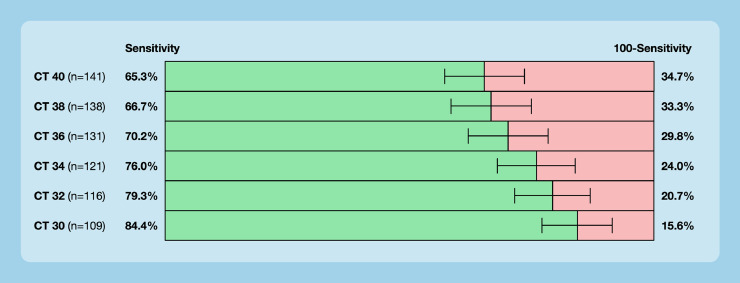

The sensitivities of the rapid antigen test in relation to adapted cycle thresholds of the reference standard are shown in Figure 3 . Sensitivity ranged from 65.3% (CT 40) to 84.4% (CT 30).

Figure 3.

Sensitivities of the rapid antigen test in relation to adapted cycle thresholds (CT) of RT-PCR. The manufacturer's recommended CT is 40.

Discussion

Our prospective cross-sectional study aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of a rapid antigen test in diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection in the real-life clinical setting of a primary/secondary care testing facility. Among the 1465 patients included, 351 presented without any symptoms. The overall sensitivity of the rapid Roche/SD Biosensor rapid antigen test was 65.3%, which is substantially lower than found in previous studies and the manufacturer's data (Mattiuzzi et al., 2020). In patients without symptoms, the sensitivity was 44%.

Various studies analyzing the diagnostic accuracy of rapid antigen tests have been conducted, with a systematic review conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration summarizing these data (Dinnes et al., 2020). The authors raised major methodological concerns and a considerable risk of bias in all previous studies. In particular, the applicability was estimated to be low because of biased patient selection. In contrast to these studies, ours paid close attention to all the requirements of diagnostic accuracy studies: (a) an adequately powered prospective cross-sectional design examining a clearly defined clinical question; (b) selection of an appropriate study population (real-life clinical setting); (c) accurate determination of the index test; (d) rigorous choice and determination of the reference standard test; and (e) optimal flow and timing. We believe that this difference in study design and methodological quality explains the significant differences in sensitivities obtained.

As a limitation, our data were obtained in a particular clinical setting in a primary/secondary care facility in Switzerland. The diagnostic accuracy measures will differ in other clinical settings because of differences in prevalence and patient population. However, we believe that the diagnostic accuracy measures in other real-life clinical settings will more likely be similar to our results compared with the very optimistic numbers provided by the manufacturers. Moreover, one particular assay from one manufacturer was studied, and therefore our results cannot be directly applied to other assays. However, without similar studies conducted with other assays, there is no reason to assume that other tests will perform better. As another limitation, the adequate cycle threshold for identifying a SARS-CoV-2 infection is disputed, with some authors arguing that a lower threshold would be sufficient. However, a lower cycle threshold is not established and the sensitivity was also limited using a lower threshold (Figure 3).

What do our results mean in clinical practice? Using the sensitivity obtained in our study, and considering a similar clinical setting in other Swiss testing facilities, we calculated the numbers of false-negative test results within one month in Switzerland. An estimated 223’219 rapid antigen-tests were done between 1th and 31th of May 2021 (compared to 541’278 RT-PCR tests) and the Roche/ SD Biosensor was used in the majority of cases (FOPH, 2021b). Considering a proportion of positive tests of 5.8% would result in 8’454 correctly identified with a SARS-CoV-2 infection but 4’493 individuals falsely classified as SARS-CoV-2 negative. While feeling safe, these individuals would probably contribute to SARS-CoV-2 transmission through inappropriate social contacts. Thus, negative test results should be treated with great caution, especially in asymptomatic individuals.

In conclusion, the accuracy of the SARS-CoV-2 Roche/SD Biosensor rapid antigen test in diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infections in a primary/secondary care testing facility was considerably lower compared with the manufacturer's data. Widespread application in this setting might lead to a considerable number of individuals falsely classified as SARS-CoV-2 negative. This test limitation should be taken into consideration when setting up public health testing strategies.

Declarations

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the local ethical committee (Kantonale Ethikkommission Bern #2020-02729).

Availability of data: The database is available on request from the corresponding author.

Funding: MN is supported by a research grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (#179334).

Authorship contributions: SJ collected data, wrote the manuscript, and contributed to the study design and interpretation of results. FSR and PB collected data, contributed to the study design and interpretation of the results, and revised the manuscript. PJ contributed to the study design and interpretation of the results, and revised the manuscript. MN designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests: MN has received research support from Roche Diagnostics outside of the present work. All other authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h5527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossuyt PMM. In: Evidence-based laboratory medicine. Second Edition. Price CP, Christenson RH, editors. AACC Press; Washington DC: 2007. Studies for evaluating diagnostic and prognostic accuracy; pp. 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Brigger D, Horn MP, Pennington LF, Powell AE, Siegrist D, Weber B, et al. Accuracy of serological testing for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: first results of a large mixed-method evaluation study. Allergy. 2021;76(3):853–865. doi: 10.1111/all.14608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujang MA, Adnan TH. Requirements for minimum sample size for sensitivity and specificity analysis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(10):YE01–YYE6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18129.8744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Coronavirus self-checker; 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/.

- CDC. Interim guidelines for collecting and handling of clinical specimens for COVID-19 testing; 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html.

- Crozier A, Rajan S, Buchan I, McKee M. Put to the test: use of rapid testing technologies for COVID-19. BMJ. 2021;372:n208. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Adriano A, Berhane S, Davenport C, Dittrich S, et al. Rapid, point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOPH. Coronavirus: disease, symptoms, treatment; 2021a. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/krankheiten/ausbrueche-epidemien-pandemien/aktuelle-ausbrueche-epidemien/novel-cov/krankheit-symptome-behandlung-ursprung.html. [Accessed June 15, 2021].

- FOPH. COVID-19 Switzerland, epidemiological course; 2021b. Available from: https://www.covid19.admin.ch/de/epidemiologic/test. [Accessed June 15, 2021].

- Iacobucci G. Covid-19: government faces criticism over pound500m plan to pilot mass testing. BMJ. 2020;370:m3482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett S, Halligan S, Thompson M, Collins GS, Altman DG. Interpreting diagnostic accuracy studies for patient care. BMJ. 2012;345:e3999. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiuzzi C, Henry BM, Lippi G. Making sense of rapid antigen testing in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) diagnostics. Diagnosis (Berl) 2020 doi: 10.1515/dx-2020-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton J. Covid-19: delays in getting tests are keeping doctors from work, health leaders warn. BMJ. 2020;370:m3755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]