Abstract

Background

SARS-CoV-2 seems mainly transmissible via respiratory droplets. We compared the time-dependent SARS-CoV-2 viral load in serial pharyngeal swab with exhaled breath (EB) samples of hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Methods

In this prospective proof of concept study, we examined hospitalized patients who initially tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Paired oronasopharyngeal swab and EB specimens were taken at different days of hospitalization. EB collection was performed through a simple, noninvasive method using an electret air filter-based device. SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection was determined with real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

Results

Of 187 serial samples from 15 hospitalized patients, 87/87 oronasopharyngeal swabs and 70/100 EB specimens tested positive. Comparing the number of SARS-CoV-2 copies, the viral load of the oronasopharyngeal swabs was significantly higher (CI 99%, P<<0,001) than for EB samples. The mean viral load per swab was 7.97 × 106 (1.65 × 102-1.4 × 108), whereas EB samples showed 2.47 × 103 (7.19 × 101-2.94 × 104) copies per 20 times exhaling. Viral loads of paired oronasopharyngeal swab and EB samples showed no correlation.

Conclusions

Assessing the infectiousness of COVID-19 patients merely through pharyngeal swabs might not be accurate. Exhaled breath could represent a more suitable matrix for evaluating infectiousness and might allow screening for superspreader individuals and widespread variants such as Delta.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Exhaled Breath, Viral Loads, Airborne Transmission

Introduction

The continuous dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 has emerged as a global health threat because of its high risk of transmissibility. Managing COVID-19 remains challenging due to unrestrained viable virus shedding, with both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients capable of spreading COVID-19 (Zou et al., 2020, Arons et al., 2020, Wei et al., 2020). Understanding the dynamics of viable virus shedding and its transmission is essential to propose infection prevention and control precautions to de-escalate the pandemic.

Commonly, the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA is carried out through routinely implemented real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) from nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs (Interim Guidelines for Collecting 2021). Alternatively, SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in several other biological materials, including saliva, sputum, olfactory mucosa, urine, faeces and plasma or serum samples of COVID-19 patients (Wang et al., 2020, Wölfel et al., 2020, Meinhardt et al., 2021, Zheng et al., 2020). Although SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected, there have been ambiguous published reports discussing the relevance and potential of these biological materials for transmission of the virus. Thus, viral transmission through these specimen types remains uncertain. However, recent studies presume a correlation between the viral load in samples taken from the upper respiratory tract and the infectiousness of viable virus (Wölfel et al., 2020, van Kampen et al., 2021, Bullard et al., 2020).

According to current knowledge, SARS-CoV-2 seems to be mainly transmissible via droplets and/or aerosols, i.e., respiratory droplets contain replication and infection-competent viruses that can reach susceptible individuals, causing infection (Morawska and Cao, 2020, Liu et al., 2020, van Doremalen et al., 2020, Lydia, 2020). Therefore, alternative sampling of COVID-19 patients, especially samples representing the lower respiratory tract, is urgently needed. Invasive sampling methods such as bronchoalveolar lavage and tracheal aspirates are described in the literature but might be impractical in routine COVID-19 diagnosis (Wölfel et al., 2020, Xiong et al., 2020). In contrast, the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in exhaled breath condensate (EBC) samples has been reported, implying exhaled breath (EB) as a promising biological matrix to examine the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 as well as its risk of contagion (Ryan et al., 2021, Ma et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2021).

The objective of this experimental proof of concept study was to evaluate the SARS-CoV-2 viral load and its progression in paired serial oronasopharyngeal swab and EB samples of COVID-19 patients. The viral load in EB samples was detected through a noninvasive and simple method using an air filter-based device, followed by routine qRT-PCR. Our study's primary purpose was to resolve whether the viral load of samples from the upper respiratory tract allows an accurate prediction of the viral load in EB, which may represent a more appropriate biological material for assessing the contagiousness of infected COVID-19 patients.

Methods

Study design

This prospective proof of concept study examined patients who initially tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on admission to hospital. In total, 187 specimens from 15 hospitalized patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were collected between July 18 and November 16, 2020. The screening consisted of collecting swabs of the upper respiratory tract (oronasopharyngeal swabs) and EB specimens and testing for the presence of SARS-CoV-2. In the statistical analysis, paired results were considered to compare the rate of the 2 sampling methods and to describe differences in the viral loads during the progression of COVID-19.

Classified according to the National Institutes of Health classification of severity of illness (National Institutes of Health (NIH) 2021) as asymptomatic or presymptomatic, mild and moderate patients were recruited to participate in the study. Participants provided informed written consent. Patients who developed a critical condition during hospitalization that led to admission to the intensive care unit and those discharged from the hospital due to recovery were excluded from the study.

The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Kiel University, Germany, approved this study (D527/20). Informed consent for COVID-19 research was waived by the data protection office of the Faculty of Medicine, Kiel University. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Specimen collection

After initial positive COVID-19 diagnosis, a simultaneous paired collection of oronasopharyngeal and EB specimens was performed. The day after the initial diagnosis of COVID-19 was set as Day 1, and specimen collection was repeated every 1–3 days during hospitalization, particularly on Days 3, 5, 7, 10 and 14.

Patients were instructed to avoid eating, drinking, smoking, chewing gum or brushing teeth 30 minutes prior to sample collection. EB specimens were collected using a filter-based device (SensAbues®, Stockholm, Sweden) consisting of a mouthpiece, a polymeric electret filter enclosed in a plastic collection chamber, and an attached clear plastic bag. The mouthpiece is designed to avoid oral fluid contamination during sampling, allowing only microparticles to pass through and be collected on the filter inside the device. The clear plastic bag indicates adequate individual use and a sufficient volume of exhaled breath passing through the electret filter (Tinglev et al., 2016, Skoglund et al., 2015, Beck et al., 2013).

The patients were instructed to inhale through the nose and tidally exhale 20 times through the mouthpiece onto the filter inside the collection device. A new device was used for each EB specimen collection. EB specimen collection was performed under the supervision of an investigator.

Next, specimens from the upper respiratory tract were collected. Oronasopharyngeal sampling was performed using sterile swabs (Nerbe Plus GmbH & Co. KG, Winsen/Luhe, Germany) following the standard recommended procedures (Interim Guidelines for Collecting 2021). Both swabs and the EB samples were stored at -80°C until extraction.

Extractioan of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and qRT-PCR

Paired oronasopharyngeal swabs and EB specimens were analysed simultaneously and under identical conditions. Viral RNA was extracted using the QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). Oronasopharyngeal swabs were extracted in 0.5 mL buffer. A 200 μL aliquot of the extract was taken and further diluted (1:1).

For the extraction of viral RNA from the filter of the EB collection device, the manufacturer's instructions were modified. The electret air filter was first wetted by frequently adding 1 mL of buffer every 5 minutes to a total volume of 3 mL. Then, the collection device was gently agitated and vortexed for 2 minutes, and an additional 0.5 mL of buffer was pipetted onto the filter. To elute the solvent from the prewetted filter, the EB collection device was placed into plastic test tubes, and 400 µL of the extracted EB samples were taken for RNA isolation. After concentration, the RNA suspension was eluted in 50 μL of buffer. A 10 μL aliquot of the sample eluate was added to a 15 µL master mix for each PCR. qRT-PCR was performed on a BioRAD CFX96 Real-Time Thermal Cycler with Maestro Software (Hercules, California) using the ampliCube Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 kit (Mikrogen, Neuried, Germany) that targets the E and Orf1a genes of the virus. Thermal cycling conditions were set at 50°C for 8 minutes and 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds and 60°C for 45 seconds.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection was determined by amplification of both genes targeted (E, ORF1a). A cut-off cycle threshold (Ct) of 40 was set as negative. The assay included an internal control for monitoring nucleic acid extraction efficacy and qRT-PCR inhibition in each reaction. A negative control was included and processed parallel to the clinical sample. The qRT-PCR analysis was replicated once for each positive sample.

SARS-CoV-2 quantification

Ct values of the targeted E gene were converted to log10 SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies/µL using calibration curves based on an in vitro transcribed (IVT)-quantified coronavirus 2019 E gene control (European Virus Archive GLOBAL, Charité University Berlin). The IVT stock solution at a concentration of 106 copies/10 µL was serially diluted to 105,104, 103, 102, 101 and 10° copies/10 µL, and 10 µL of each was added to the master mix. qRT-PCR of the calibration was performed under the conditions described above.

Statistical analyses

The results are presented as the means or medians, SDs and interquartile ranges (IQRs) unless stated otherwise. Statistical details for each analysis are described in each figure legend or in the respective part of the text. Student's t-test was used to assess group differences for continuous numerical variables, and a one-tailed P-value was calculated. Additionally, a Welch t-test correction was applied because of unequal sample distribution variance. P-values were considered to be significant at P <0.05. No data points were excluded. Statistical analyses were carried out using R 2020 version 1.3.1093 and Origin 2020 version 9.70.

Results

A comparison of oronasopharyngeal swabs and EB samples is required to analyse the correlation between the respective viral loads. Here, we tested 187 specimens of 15 hospitalized patients with a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Of these, 87 were of the upper respiratory tract (oronasopharyngeal swabs), and 100 EBs were collected with a filter-based device (Supplementary Table 1). The included COVID-19 patients had a mean age of 56 years (IQR 33–79, range 27–85).

SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection was determined with qRT-PCR. All 87 swabs from the upper respiratory tract tested positive. Moreover, 70 of the 100 EB specimens tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, whereas the remaining 30 were classified as negative due to Ct values of > 40. The negative tested EB samples mainly occurred 7 days after clinical onset, i.e., 16 of 30 (53.3%) EB samples taken on days 7–14 tested negative, whereas only 14 of 70 (20.0%) EB samples collected on days 1–5 showed a negative result (Supplementary Table 2).

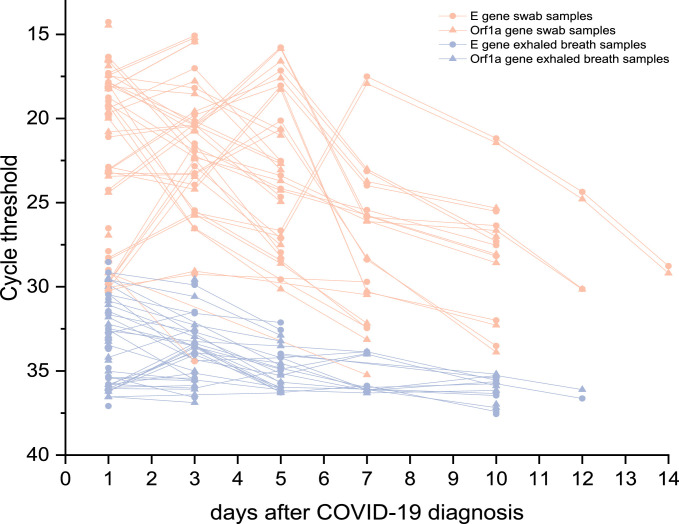

Figure 1 provides an overview of SARS-CoV-2 samples from the upper respiratory tract and EB of all patients enrolled in this study. Individual COVID-19 progression is represented by the Ct values of the targeted E and Orf1a genes of both specimen types. As shown, samples of the upper respiratory tract exhibited lower Ct values than the simultaneously collected EB samples. The mean difference in Ct values was 10.64. Furthermore, neither targeted E nor Orf1a genes showed a significant difference in oronasopharyngeal swabs (CI 99%, t(171) = -0.184, P = 0.855) nor in EB samples (CI 99%, t(137) = -0.447, P = 0.656) (Supplementary Figure 1). The mean differences between the Ct values of replicates of swabs and EB samples were 1.26 and 0.88, respectively.

Figure 1.

Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract and EB samples of 15 infected hospitalized patients. Progression of Ct values of the targeted E gene and Orf1a gene in serial swabs (n = 87) compared with EB samples (n = 70) of each individual during the 14 days after COVID-19 diagnosis

The Ct values were used for further calculation of the respective viral RNA load of each sample. Viral loads of both sampling methods were calculated using a calibration curve (correlation coefficient R2 = 0.9984, Supplementary Figure 2) with a quantification range shown to be between Ct values of 17.48 (106 copies/10 µL) and 38.56 (1 copy/10 µL).

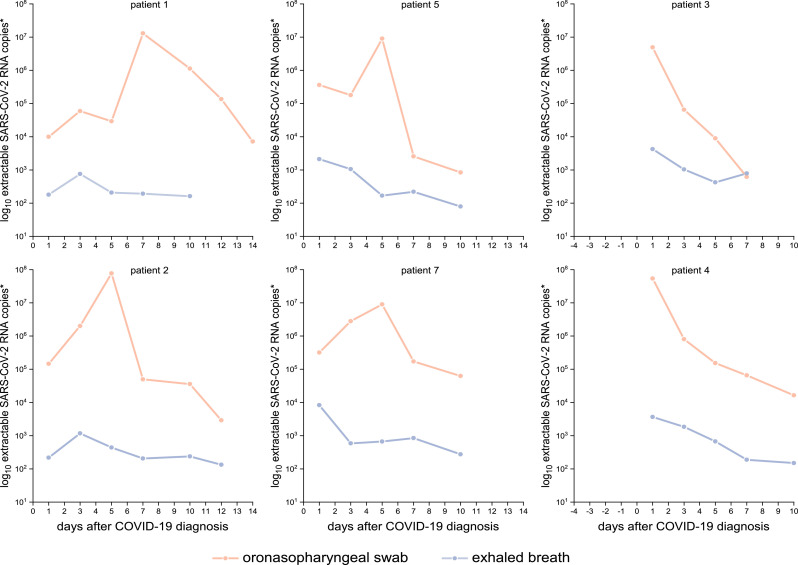

The typical progression of COVID-19 evaluated through samples of the upper respiratory tract begins with a steady increase in viral load until reaching a shedding peak, which is followed by continuously decreasing viral loads. Patients 3 and 4 merely showed decreasing viral loads due to inclusion in the study after being symptomatic 3–5 days before being tested positive. The EB samples show a different progression compared with the swab samples, with viral loads marginally increasing or remaining nearly constant during the 14 days after diagnosis of COVID-19 (Figure 2 ), resulting in a higher variance of the viral load of oronasopharyngeal swabs compared with the EB samples.

Figure 2.

Comparison of viral load progression of swab and exhaled breath samples from six selected COVID-19-patients over 14 days. *Extractable log10 SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies per oronasopharyngeal swab and per 20 times exhaling through EB collection device.

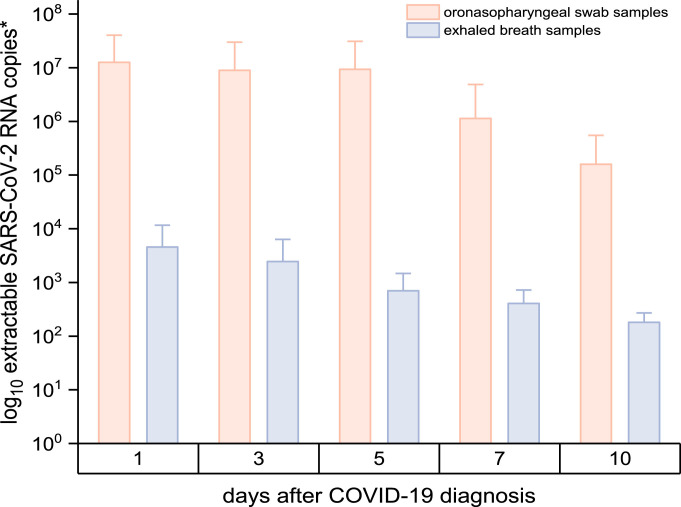

Figure 3 shows the viral load per sampling device, i.e., the extractable number of SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies of an oronasopharyngeal swab and EB collection device (after exhaling 20 times). By comparing the number of SARS-CoV-2 copies, the viral load of the oronasopharyngeal swabs (n = 87) was significantly higher (CI 99%, t(86) = 3.526, P <<0,001) than the viral load of the EB analysis (n = 70). The mean viral load per swab was 7.97 × 106 (IQR = 1.63 × 104 - 4.17 × 106, range 1.65 × 102 - 1.40 × 108), whereas the mean viral load of EB samples (on day 1–10 after diagnosis) was 2.47 × 103 (IQR = 2.17 × 102-1.85 × 103, range 7.19 × 101-2.94 × 104). Estimating that exhaling 20 times is approximately equivalent to 10 L of exhaled breath (Hallett et al., 2020), a viral load up to 2.94 × 103 can be found in 1 litre of exhaled breath.

Figure 3.

SARS-CoV-2 viral load in oronasopharyngeal swabs and EB samples. *Extractable number (mean [SD]) of log10 SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies per oronasopharyngeal swab and per EB collection device. Samples were collected on day 1 (swabs n = 28, EB n = 26), day 3 (swabs n = 20, EB n = 17), day 5 (swab n = 16, EB n = 13), day 7 (swab n = 12, EB n = 6) and day 10 (swabs n = 8, EB n = 7) after COVID-19 diagnosis.

All patients have shed SARS-CoV-2 in exhaled breath on at least 1 occasion. Nevertheless, the viral loads emitted by patients show a high heterogeneity, e.g., 9.83 × 101 to 2.94 × 104 virus copies per 20 times exhaling on day 1 after the first diagnosis.

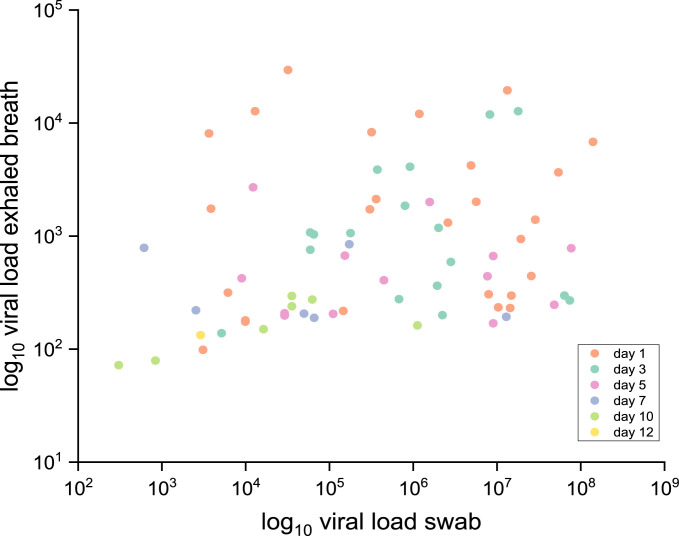

Finally, the viral loads of 70 simultaneously collected paired samples of oronasopharyngeal swabs and EB did not correlate (correlation coefficient R2 < 0.01); presented in Figure 4 .

Figure 4.

Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 viral load of paired oronasopharyngeal swab and EB samples. The viral load of samples (n = 70) of both specimen types simultaneously collected on respective days after COVID-19 diagnosis is shown by means of log10 SARS-CoV-2 RNA copies (R2 < 0.01).

Discussion

The evaluation and analysis of EB are important to extend existing knowledge, providing evidence for SARS-CoV-2 quantification using this biological matrix. Although EB sampling seems challenging, it is a promising biological matrix to explore, especially as it is a noninvasive and more comfortable sampling method than oronasopharyngeal swab sampling and can be easily repeated. The primary purpose of this pilot study was to detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA in EB and compare the viral load of simultaneously collected serial swabs and EB samples taken at different time points during hospitalization of COVID-19 patients. Further details of the medical condition of the patients were not included in the evaluation. This study is comparable to other studies of similar design aiming to find viral RNA in different biological materials, e.g., sputum, urine, faeces and plasma or serum (Wang et al., 2020, Wölfel et al., 2020, Zheng et al., 2020). However, it is still elusive whether these biological matrices correlate with the infectiousness of patients diagnosed with the virus (Leung Nancy, 2021).

EB sampling is not common for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although recent studies have reported detection of the virus in exhaled breath condensate (EBC) samples (Ryan et al., 2021, Ma et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2021), no documented time-dependent progression of SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in EB has yet been described. To fill this gap, we collected serial samples for 14 days after COVID-19 diagnosis to analyse the progression described through Ct values and viral loads. To ensure a comparison with valid outcomes the commonly used sampling method of oronasopharyngeal swabs was performed in parallel to analyse the viral loads of the 2 different specimen types collected from each patient at the same time.

EB testing was performed using a simple device containing an electret air filter, which is commonly used to detect nonvolatile exogenous and endogenous molecules, including drugs, metabolites, proteins and other biomarkers (Tinglev et al., 2016, Skoglund et al., 2015, Beck et al., 2013, Lovén Björkman et al., 2021). The results of our study clearly show that viral RNA is detectable as well. Furthermore, the method provides reproducible and reliable results since the mean difference between Ct values of replicates of EB samples was shown to be 0.88. This mean difference was lower than that evaluated for swab samples (1.26).

Analogous to other specimen types, such as sputum, urine, faeces or serum (Wang et al., 2020, Wölfel et al., 2020, Zheng et al., 2020), both of the targeted genes (E and Orf1a) of SARS-CoV-2 can be detected in respiratory droplets of EB with no significant difference between the Ct values (CI 99%, t(137) = -0.447, P = 0.656). Ryan et al. recently reported that other genes, such as the N and S genes, can also be found in EBC samples (Ryan et al., 2021), indicating that a sufficient amount of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in EB is perceptible.

Although EB samples show a lower viral load than swab samples, SARS-CoV-2 was detected in EB samples even 12 days after COVID-19 diagnosis. Furthermore, the progression of viral loads described in this study remains nearly constant over 14 days. The viral loads slightly decreased in the EB of COVID-19 patients 7–10 days after diagnosis. However, in contrast, the viral load of swab samples slowly increases, leading to a shedding peak and subsequently decreases (Wölfel et al., 2020, Sun et al., 2021), confirming the results of studies that present a similar progression of COVID-19.

While interpreting the data, it should be considered that the days after diagnosis do not necessarily equate with the days after onset, as some patients were not tested immediately due to delayed hospital submission. Hence, 7 days after a positive test may represent the end of the infection of some patients, whereas others might exhibit the shedding peak because of early detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure 1).

EB samples showed a significantly lower viral load (CI 99%, t(86)=3.526, P <<0,001) than swab samples. Our results of a mean viral load of 2.47 × 103 in EB samples are comparable to the results of Ma et al. evaluating EBC (Ma et al., 2020). Here, we show the measured mean viral load of 2.47 × 103 (range 7.19 × 101-2.94 × 104), representing the amount of SARS-CoV-2 obtained by breathing 20 times into the device. Thus, up to approximately 2.94 × 103 can be found in 1 L of exhaled breath. Considering the typical respiratory rate for a healthy adult at rest of 18 breaths per minute (Barrett et al., 2012), an infected patient would shed approximately 3.89 × 103–1.59 × 106 per hour simply via regular breathing; this amount of viral load could remain in the air for at least several minutes (Lydia, 2020). While analysing the difference in the viral load of EB and swab samples, the distinctive sampling method, as well as the biological material, should be considered. Cells of the oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal mucosa containing the viral RNA were mechanically abraded using a swab, leading to an artificially generated higher viral load in swabs. In comparison, the collection of respiratory droplets in exhaled breath is noninvasive and consequently does not undergo such mechanical stress.

Ljungkvist et al. and Beck et al. describe the collection efficiency and the recovery from the filter to be more than 90% (Ljungkvist et al., 2017, Beck et al., 2011). Moreover, the collection efficiency seems to be 99% in the particle diameter range of 0.5–20 μm. As respiratory droplets are typically 5–10 µm in diameter, it can be assumed that the collection efficiency of the system lies between 90% and 99%. Hence, the sampled viral load measured from EB samples almost completely translates to the actual viral emission. Although the mean viral load in EB samples was low, it represents the minimal viral load that would have been exhaled into the environment by the patient during tidal breathing. Consequently, a non-infected close contact would be exposed to at least this viral load in a non-ventilated room. Hence, talking, singing or even coughing and sneezing might cause higher aerosol emissions (Lydia, 2020, Asadi et al., 2019). In contrast, patients swallow the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal mucus with cells containing viral RNA. Therefore, there is a high possibility that even though the viral load of swab samples is significantly higher, the viral amount found in swabs is not fully shed into the environment, as is the case when exhaling.

Each patient enrolled in this study exhaled SARS-COV-2 RNA at least once. However, the emitted amount of virus copies is highly heterogeneous as some patients shed for example 92 virus copies per 20 times exhaling, whereas others may exhale 3 orders magnitude higher (2.94 × 104) at the very beginning of the illness. Infection risk among the population could increase with the amount of EB viral shedding. Therefore, EB testing may provide a means to distinguish between non-, low- and super-spreader for the aerosol route of transmission.

It is commonly discussed that COVID-19 patients are most infectious in the first week of the infection (Wölfel et al., 2020, Sun et al., 2021). Here, we show that patients might exhale a significant amount of the virus in the later stage of the infection. However, all EB samples collected on day 14 after COVID-19 diagnosis tested negative. Thus, even though swab samples show a positive result of SARS-CoV-2 with Ct values of 28–29 on day 14, the paired EB sample could be SARS-CoV-2 negative. Nevertheless, this is not always the case, as similar Ct values of swab samples of another patient (Ct27.88, viral load of 1.23 × 104) showed a positive paired EB sample with a Ct value of 28.53, resulting in a viral load of 2.94 × 104 per 20 exhalations. These results clearly indicate that even after 2 weeks of infection, high viral loads can be found in the upper respiratory tract swabs, but the patient might not shed the virus via exhalation and most likely is no longer infectious. Nevertheless, it should be considered that this study does not examine the comparative infectiousness of the sampled individuals since no viral culture was performed.

Lastly, no correlation between the viral load of swab samples and EB samples was found (Figure 4). In contrast, Pan et al. showed that sputum and swab samples seem to correlate (Pan et al., 2020). This correlation is most likely due to both specimen types being collected from the upper respiratory tract, whereas exhaled breath mainly originates from the lower respiratory tract.

As mentioned earlier, SARS-CoV-2 is mainly transmitted via respiratory droplets (Morawska and Cao, 2020, Liu et al., 2020, van Doremalen et al., 2020, Lydia, 2020, Leung Nancy, 2021).

Hence, assessing the infectiousness merely through swabs of the upper respiratory tract might not be suitable in all cases.

Conclusions

It appears that even though swabs from the upper respiratory tract might serve as an efficient tool in COVID-19 diagnostics, the oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal mucosa does not grant an accurate prediction of how many virus copies are actually emitted by infected patients.

In conclusion, EB could serve as a more suitable biological matrix for evaluating the infectiousness of COVID-19 patients. Using a simple filter-based device is a promising method for detecting SARS-CoV-2 viral load in EB. The EB viral shedding can last during the course of illness for up to 12 days after the first diagnosis. We strongly believe that exhaled breath testing is of tremendous importance to overcome the challenges in managing COVID-19 and should be included in infection prevention and control precautions. Further research on the viability of SARS-CoV-2 in EB could change the course of the outbreak, minimize infection risks among the population, and make virus shedding more understandable, allowing screening for superspreader individuals and widespread variants such as the Delta variant.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

M.M. contributed to the design and conception of the study, collected specimens, carried out all experimental work, including viral qRT-PCR of all specimens, prepared the figures, performed statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. T.K. conceived, designed, and supervised the study. T.B., S. H.-R., A.-C.K. were involved in recruiting COVID-19 patients and collecting specimens. All authors revised and approved the manuscript.

Correspondence and request for materials should be addressed to T. Kunze.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support by DFG within the funding programme ‘Open Access Publizieren’. We gratefully acknowledge SensAbues®, Stockholm, Sweden, and John Trainor for providing us with the filter-based devices that were used for EB specimen collection. We thank the MVZ Medizinisches Labor Nord, Kiel, Germany, especially Ulrich Klostermeier and Andrea Kruck for their analytical and technical contributions. Angelika Offt from the data protection office of the Faculty of Medicine, Kiel University, is acknowledged for her helpful advice for the study protocol on data protection. We thank the Interdisciplinary Centre for Statistics and Anna Titova, Institute for Statistics and Econometrics, Kiel University, for the fruitful discussions about statistical analysis and study conception. We would like to give our sincere thanks to the hospital staff that supported us in recruiting the patients and collecting the specimens . The authors are most grateful to all COVID-19 patients for participating in this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.07.012.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Arons MM, et al. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Transmission in a Skilled Nursing Facility. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadi S, et al. Aerosol emission and superemission during human speech increase with voice loudness. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2348. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38808-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett KE, Barman SM, Boitano S, Brooks HL. 24th edition. McGraw-Hill Med; New York: 2012. Ganong's review of medical physiology. [Google Scholar]

- Beck O, et al. Demonstration that methadone is being present in the exhaled breath aerosol fraction. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2011;56:1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck O, et al. Detection of drugs of abuse in exhaled breath using a device for rapid collection: Comparison with plasma, urine and self-reporting in 47 drug users. J Breath Res. 2013;7:26006. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/7/2/026006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullard J, et al. Predicting infectious SARS-CoV-2 from diagnostic samples. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(10):2663–2666. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett S, et al. Physiology, Tidal Volume. updated 2020 Jun 1. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482502/ (accessed March 26, 2021)

- Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens for COVID-19. 2021 Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html (accessed March 3, 2021).

- Leung Nancy HL. Transmissibility and transmission of respiratory viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;22:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00535-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, et al. Aerodynamic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in two Wuhan hospitals. Nature. 2020;582(7813):557–560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungkvist G, et al. Two techniques to sample non-volatiles in breath-exemplified by methadone. J Breath Res. 2017;12:16011. doi: 10.1088/1752-7163/aa8b25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovén Björkman S, et al. Peanuts in the air - clinical and experimental studies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:585–593. doi: 10.1111/cea.13848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydia Bourouiba. Turbulent Gas Clouds and Respiratory Pathogen Emissions: Potential Implications for Reducing Transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:1837–1838. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, et al. COVID-19 patients in earlier stages exhaled millions of SARS-CoV-2 per hour. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;28:ciaa1283. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt J, et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24(2):168–175. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawska L, Cao J. Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2: The world should face the reality. Environ Int. 2020;139 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. 2021 Available at: https://files.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/guidelines/covid19treatmentguidelines.pdf (accessed March 16, 2021). [PubMed]

- Pan Y, et al. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:411–412. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan DJ, et al. Use of exhaled breath condensate (EBC) in the diagnosis of SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) Thorax. 2021;76:86–88. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoglund C, et al. Clinical trial of a new technique for drugs of abuse testing: A new possible sampling technique. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun K, et al. Transmission heterogeneities, kinetics, and controllability of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2021;371(6526):eabe2424. doi: 10.1126/science.abe2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinglev ÅD, et al. Characterization of exhaled breath particles collected by an electret filter technique. J Breath Res. 2016;10:26001. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/10/2/026001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doremalen N, et al. Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kampen JJA, et al. Duration and key determinants of infectious virus shedding in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):267. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20568-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Types of Clinical Specimens. JAMA. 2020;323:1843–1844. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei WE, et al. Presymptomatic Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 — Singapore, January 23–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(14):411–415. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wölfel R, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, et al. Transcriptomic characteristics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:761–770. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1747363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S, et al. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang province, China, January-March 2020: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1443. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, et al. Breath-, air- and surface-borne SARS-CoV-2 in hospitals. J Aerosol Sci. 2021;152 doi: 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2020.105693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.